As the first wave of opinions that came hard on the heels of the gas contract between Russia’s Gazprom and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) subsided, analysts started to look in earnest into what the two parties had actually signed. For Russia, the accords, hammered out for well over a decade, mean no less than a window to Asia as they enable it to launch the development of gas fields of Eastern Siberia and the Far East and speed up the socio-economic development of these regions.

COST ESTIMATES AND FUNDING

Cold hard facts are that the contract provides for the supply of up to1.032 trillion cubic meters of natural gas to China over thirty years, starting from the last quarter of 2018. Both sides reserve the right to postpone deliveries by two years, depending on the readiness of the infrastructure. The contracted volume of 38 billion cubic meters of gas a year is to be attained within five years from the beginning of deliveries, i.e. in 2023 (or in 2025, if the parties apply the postponement provision).

Yakutia’s Chayanda field will become the main resource for implementing the contract, with proven reserves of 1.3 trillion cubic meters and planned production level at 25 billion cubic meters a year. Later, Russia will tap the Kovykta field in the Irkutsk region (with estimated reserves of 2.5 trillion cubic meters and production level at 40 to 50 billion cubic meters a year). The licenses to develop both gas fields belong to Gazprom which also holds the right to a number of satellite deposits. They will be developed at subsequent stages of the Eastern Gas Program. In addition, the oil companies Rosneft and Surgutneftegaz can recover their reserves of associated petroleum gas under this contract.

Given the potential resource of these fields, it would not be surprising if Russia and China negotiate, ahead of the beginning of gas supply, an increase in deliveries to at least 50 to 55 billion cubic meters a year. Russia will build the Power of Siberia pipeline from Eastern Siberia to China, but one string of the pipeline with a capacity of up to 33 billion cubic meters a year will not be sufficient to reach the contracted volume of supplies, as the amount of sales gas will be down 10% to 12% after transportation and processing. But a twin pipeline gives all the opportunities to boost supplies to China by 50 percent.

China might use the existing status quo for striking a contract with another Russian exporter, for example Rosneft, whose CEO Igor Sechin is lobbying, among others, for the cancellation of monopoly on pipeline gas exports. However, the Russian government believes that competition among state-run companies with the only buyer at the other end makes no sense. It is fraught with pressure on prices, lower receipts, and, consequently, lower budget revenue. Sechin seems to be aware of that. When the Rosneft CEO first voiced the initiative to liberalize gas exports eastwards at a session of the government commission on the fuel and energy sector in Astrakhan in early June, he conceded that the issue was debatable. Raising it now, Sechin, who happens to be secretary of the commission, hopes to secure easier and more advantageous terms for selling gas to Gazprom.

In addition to the two strings of Power of Siberia to custody transfer stations on the border with China, Russia plans to build a large gas processing plant in Belogorsk, Amur region, for reclamation of commercial helium and ethane (raw material for gas chemistry). Also in Belogorsk, third-party investors (a preliminary agreement has been signed with Sibur) consider building a gas-chemical facility which will buy ethane for processing.

Russia will require $55 billion worth of capacities to execute the contract, according to government and Gazprom officials. The figure is a sum total of the estimated cost of the development of the Chayanda field (440 billion rubles, or $3 billion in 2012 prices), the first string of Power of Siberia (770 billion rubles, or $23 billion) and the projects to process gas and increase gas production and expand the gas transportation network, in accordance with an agreement between Gazprom and CNPC.

The question is how advantageous the contract is to Gazprom and the Russian government and how fast the investment will pay back.

Financial parameters of the contract are a commercial secret, but Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller said it was worth $400 billion over thirty years. Accordingly, 1,000 cubic meters of gas sell for $387, which matches the average price of Gazprom’s supplies to Europe and Turkey in 2013. It is, of course, a rough estimate of contract value. A formula pegged to an oil and petroleum products basket and adjusted for inflation will be used to calculate the gas price. The above estimated gas price can be considered correct if the price of oil stands at around $105 per barrel.

It appears that the projected revenue from the contract will be approximately eight times higher than the expected investment. Furthermore, it means investment in the Russian economy, with large orders for pipes, compressors, mining sets, gas treatment equipment, construction works, etc. Direct investment will have to be disbursed over a decade with five to six billion dollars a year on the average without ripple effects related to the development of Eastern Siberia territories.

The Russian government plans to reduce to zero the mining tax on gas and condensate, but since the Tax Code introduces the coefficient of 0.1 for Eastern Siberia fields, future losses from the measure will only amount to 2 to 3 dollars per 1,000 cubic meters. Government officials believe that as the gas price under the contract is high enough, Gazprom does not need an incentive for export duty, the prime source of deductions from gas producers. It makes up 30% of product’s customs value, or $116 per 1,000 cubic meters if we apply the above gas price on the border with China. Over thirty years, the export duty will fetch nearly $120 billion, or up to $4.4 billion annually.

As for Gazprom, it will collect some $270 per 1,000 cubic meters of gas after export duty deduction. According to our calculations, the company will earn approximately $22 billion in the first five years and $10 billion in each subsequent year. This money has to cover operating costs and pay back the $55 billion investment.

Net lifting costs are estimated at 20 to 25 dollars per 1,000 cubic meters in mining and up to 10 dollars per 1,000 cubic meters in transportation (the cost of power gas plus pipeline maintenance). Also, sales of oil and condensate from the Chayanda field will fetch Gazprom about $1 billion a year, allowing the company to recover the invested capital, including financing costs, within a decade. In case it secures cheaper state funding, the payback period might be even shorter, as President Vladimir Putin said at the meeting in Astrakhan.

Of course, the investor should meet the cost estimates in implementing the project, so control over quality of work and expenses is an unquestionable priority. The allegations that the project is disadvantageous for Russia and Gazprom from the beginning do not correlate with reality. There are risks related to China’s being the sole purchaser of this gas, as it might exploit the situation to secure additional concessions. Yet strictly speaking, this rigid supplier-consumer dependence is natural in deliveries of pipeline gas. To hedge against these risks, long-term contracts are concluded, with a take-or-pay clause which protects the supplier from the sole importer’s whims.

CHINA’S GAINS

Why then did the intractable China ink the deal on the second day of Putin’s visit which seemed to have nothing to do with gas contracts, with everybody assuming that the signing would not take place again? The answer is gas from Eastern Siberia is very important for China’s future energy balance and sustainable development of its northeastern regions. Beijing, seeing the acute geopolitical setup and Moscow’s obvious interest in showing the West it has alternative options for economic cooperation and trade, decided to bargain for an extra discount.

But when China saw that Russia would not give up profit for show’s sake, it abandoned the dead-end tactic. After Gazprom failed to reach an accord with CNPC on gas price in 2013, it put all work on hold in the east, and did not even include the cost of developing the Chayanda field and building the Power of Siberia pipeline in its investment program for 2014. For China it only meant a further delay in gas supply, which would come in sufficient quantity not earlier than in five years as it is. Now that the situation has changed, the work on infrastructure can be resumed quickly.

Although the price is quite comfortable for the supplier, it meets the buyer’s interests as well. On the one hand, it is considerably higher than the initial target price of the Chinese negotiators. They wanted Russian gas to compete with coal which was the main local fuel in China. At one point, they sought to make the Henry Hub price a reference point, which had been several times lower than the Asian and European levels in the past few years. On the other hand, the price of Russian gas is approximately 15 percent lower than the average price of liquefied gas imported by China in 2013 ($444 per 1,000 cubic meters). Present-day LNG prices in Asia start from $600.

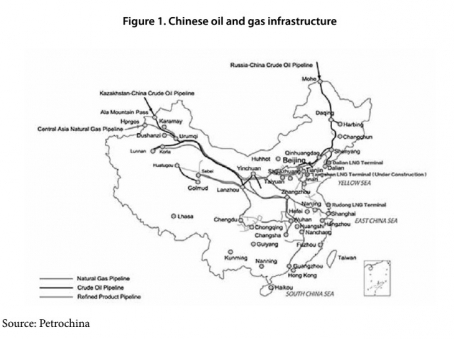

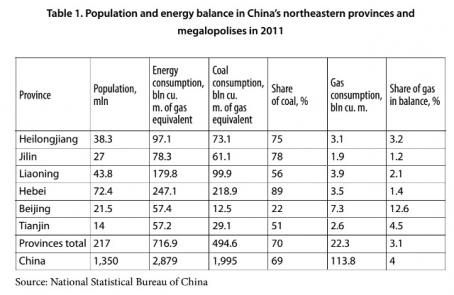

A map of China’s gas infrastructure shows that the country’s northeast (Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning and Hebei, not counting the Beijing and Tianjin municipalities) with a population of 180 million are actually cut off from the West-East gas pipeline, i.e. from the key fields in western provinces linked with the main consumer markets on the coast. Gas from Central Asia, the largest source of imported gas for China, is also supplied to that area, but it does not reach the northeast, with the exception of the Chinese capital. Gas consumption levels in these provinces ranges between 1.4% and 3.2% of the energy balance, i.e. twice as low as China’s average.

The share of coal in the energy balance of these provinces ranges from massive 56% to nightmarish 89%. In 2011, gas consumption only made up 12.5 billion cubic meters mainly produced locally. General gas statistics are buoyed by two megalopolises having the status of municipalities – Beijing and Tianjin – which adopted a strategy to phase out coal consumption. As of 2011 however, only Beijing could boast a mere 22% share of coal and a 7% share of gas. Tianjin barely exceeded the average national gas consumption level.

The situation should change, and it will definitely change in a long term. Changes require new reliable and relatively cheap sources of gas imports as domestic fuel production has increasingly failed to keep pace with demand in the past five years.

According to CNPC, which is responsible for preparing infrastructure in China (high-pressure gas pipelines, distribution networks and underground gas storage facilities which level out seasonal fluctuations in demand), the pipe will run from the border to Hebei, Beijing and Tianjin, ensuring gas distribution across the whole northeast of the country. China estimates it will require a total of $15 to $20 billion of investment.

The thirty-eight billion cubic meters of gas a year fixed in the contract will substitute some 50 million tons of coal and reduce CO2 emissions by 55 million tons, and sulfur dioxide emissions by approximately one million tons. This will greatly benefit China’s northern provinces where the beginning of the heating season compares to ecological disaster.

FROM EUROPE TO ASIA

And what about Europe? The Chinese contract has no direct impact on supplies of Russian gas to the European Union. It envisions the development of new gas fields in Eastern Siberia which can hardly be used for gas exports to Europe. Nothing threatens Gazprom’s long-term contracts with European companies to supply up to four trillion cubic meters of gas in the next 25 years. It is another matter that a lack of new long-term contracts with Europe will reduce or even stop investment in the resource portfolio intended for the European market. On top of that, Russia plans to resume the discussion with CNPC over gas sales from Western Siberia through the Altai pipeline, and this will directly tap the gas reserves which Russia has long used for exports to the West.

On the other hand, the Chinese contract is a new source of export revenue for Gazprom and customs revenue to the Russian budget, which reduces Russia’s financial dependence on gas sales to European countries. Although the contract only accounts for 25 percent of current European proceeds, it is still organic diversification delivering more revenue from new sources. If Russia and China boost gas cooperation, gas sales revenue from this source might increase to 45-50 percent.

The Chinese gas market is only a part of the Asian market, although the most promising one in terms of capacity. The share of gas in the balance of such industrialized countries as Japan (21%) and South Korea (16%) is still lower than the average for countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), hence there is a potential for growth. Due to geographical and infrastructure constraints, the Chinese contract cannot be followed up with supplies to other countries of the region, yet it will obviously encourage other potential partners from the gas-hungry Asian-Pacific region to more actively cooperate with Russia in other projects. For example, Japanese lawmakers are already lobbying a project for building a gas pipeline from Sakhalin, despite the fact that it will require an overhaul of the entire Japanese gas supply system. If this project is not implemented, Japan will be the first in the buyers’ queue for liquefied natural gas produced in Russia’s Vladivostok and Sakhalin.