Ukraine’s real birthday is December 1st, not August 24th. In August 1991, Ukraine was largely a bystander to events unfolding elsewhere, unless you count the fact that Mikhail Gorbachev’s longer-than-expected holiday was on then-technically Ukrainian territory in Crimea. Ukraine’s leader Leonid Kravchuk prevaricated during the first two days of the coup. When confronted by General Valentin Varennikov in his office, Kravchuk played for time by asking to see the coup representative’s formal credentials. Kravchuk would like this to seem brave; but it was also the classic delaying tactics of a Soviet bureaucrat. Nor was there much pressure on Kravchuk from below; there were no mass demonstrations in Kiev during the coup’s crucial first two days. Though Rukh (People’s Movement of Ukraine) then deserves credit for making sure the Rada (parliament) seized the initiative and declared independence on Saturday the 24th, before all-Soviet institutions swung back into action on Monday the 26th. Small margins matter. Rukh knew not to trust opportunist “national communists” like Kravchuk. Still less the still strong Communist Party of Ukraine whose less-than-principled support for independence was designed to save itself from potential purges emanating from Yeltsin’s Russia. As party leader Stanislav Hurenko eloquently put it in a private caucus meeting before the vote: “We must vote for independence, because, if we don’t, we’ll find ourselves up to our ears in shit.”

But in truth Ukraine’s opportunity to act in August 1991 was created by the collapse of central power elsewhere. In December 1991, on the other hand, the Ukrainians were active players. The decisive vote in the Ukrainian independence referendum on December 1st defined the Soviet end-game, making it possible for Yeltsin to pay mere lip-service to Gorbachev’s final version of his plans for a new union. And in the confusion that surrounded the end of the Soviet Union, it was the Ukrainian position that prevailed. The ‘Commonwealth of Independent States’ meant precisely that: the new independent states had certain common interests, but the CIS was not a sovereign replacement for the Soviet Union. Ukraine deserves more credit for its crucial role in ending the Union than it is credited with in most recent retrospectives.

Still, either date makes Ukraine twenty years old, between rival definitions of maturity at eighteen or twenty one. So what have we learnt in these twenty years? A first point would be to be wary of making predictions even for the next twenty years. The “rules” of Ukrainian politics and society, even the basic parameters, are not as stable as they seem. Few predicted the Orange Revolution in 2004; few predicted that it would end so badly. A second point is that Ukraine is still half passive, half active, as it was in 1991: it sometimes makes its own luck, but too often only when it is forced to act by events elsewhere.

THE VALUE OF INDEPENDENCE

The first point of substance is that Ukrainian elites value independence. Not because they value the nation-state in itself, but because it provides a protected space for self-enrichment. With the election of Viktor Yanukovych as President in February 2010, Ukraine passed the ‘Lukashenka test’. Having pressed all the buttons of Russian-speaking and Russophile voters to get elected, like Lukashenka in 1994, Yanukovych has governed (after an initial period of adjustment) as a gosudarstvennik (statist), just like Lukashenka before him. If neither man has been willing to compromise independence, then, barring catastrophes, it is hard to think of a politician who would.

The elite value the state to guard their own interests, but that doesn’t mean the Ukrainian state is just one giant krysha (protection racket). No strong challenge to the state idea has emerged, despite expectations in 1991. The blue-and-white ‘counter-revolution’ in winter 2004 drew on some strong negative sentiments and stereotypes, but it had no alternative Weltanschauung or ideologue. Some have argued that Kuchma’s former Chief of Staff Yevhen Kushnariov, who died in an allegedly suspicious hunting accident in 2007, could have been one. In which case God help the south-east: Kushnariov was no Vaclav Havel. Controversial Education Minister Dmytro Tabachnyk has recycled negative stereotypes, but nothing more. The south-east Ukrainian version of Ukrainian identity is still mainly an act of dissidence or dissonance, as with the restoration of the statue to Catherine II in Odessa in 2007; or of passive resistance in everyday life. As Volodymyr Kulyk has written, the ‘other Ukraine’ has been much more successful in undermining the Ukrainophone nationalist project in mainstream media discourse, where dual language use is portrayed as consensual and single users of either Ukrainian or Russian are marginalized as ideologues.

Public opinion shows extensive soft support for statehood. Interestingly, the main factors shifting sentiment since 1991 have been either economic or external. Regular surveys by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology show that support for independence has dipped during times of economic crisis, particularly in the early 1990s and in 1998-9; but has risen when Russia (not Ukraine) has been in conflict with its neighbors, most notably in 1994 (the beginning of the first Chechen war) and 2008 (the war in Georgia). Overall, apart from the dip in the early 1990s, support for Ukrainian independence has remained remarkably stable at around three-quarters of the population, even if some of this support is somehow second-hand.

The ‘state idea’ is vague, however. As Machiavelli put it in his Discourses on Livy, “the beginnings of religions and of republics and of kingdoms must have within themselves some goodness, by means of which they obtain their first reputation and their first expansion.” But even would-be state patriotism in Ukraine suffers from the general weakness of ideology. Like the Russian equivalent, the constitutional provision banning state ideology is largely redundant. Ideophobia is dominant. There is widespread agreement that Ukraine needs a ‘civic’ rather than an ethnic identity, but there is nothing “in the box.” Something has to give the cives substance. France has Marianne, plus liberty, equality, fraternity and laХcitО. The U.S. has the melting pot myth; Scandinavia has welfare-state tolerance; post-war Germany the Verfassungspatriotismus of making a success of democracy at the third attempt.

But Ukraine has no equivalent myth of the cives. The Orange Revolution could have provided one. The events of late 2004 were arguably three revolutions in one, with mobilization in the west and center being rivaled, if in no way equaled, by a similar coming of age in the east and the south; but the two could have been brought at least closer together as a general myth of civic activism.

This ought to have been helped by the fact that Ukrainian elites have always relied on the political culture myth that “Ukraine is not Russia.” Leonid Kuchma’s famous book of the same name was not really about ethnic or religious or even historical differences – these are too divisive. The clichО that “Ukraine is not Russia” relies more on a narrative that depicts Ukrainians as more peaceful, less imperialist and more individualistic than the Russians – which during the Orange Revolution was expressed as the myth that Ukrainians prefer “tents” over “tanks.”

Unfortunately, the Ukrainian elite are interested in civic nationalism but not in the cives; and are reluctant to give real substance to any myth that would empower the citizenry. Even so, it is exceptionally short-sighted of the Yanukovych regime to press for the removal of the Orange Revolution from school history texts for narrowly partisan reasons.

UKRAINE IS NOT (A PUTIN’S) RUSSIA

This general historical clichО is often transferred to contemporary politics. The next few years under Yanukovych will test the academic side of the thesis that “Ukraine is not Russia,” namely that Ukraine is “pluralistic by default” and that centralizing power is therefore as difficult as enforcing it. But most of the reasons why Yanukovych’s Ukraine is unlikely to create some softer version of Putinist ‘managed democracy’ are linked to contingent and structural factors rather than political culture.

The first obvious starting difference between Ukraine in 2010 and Russia in 2000 is that there was no ‘Operation Successor’ in Ukraine, even via Yushchenko’s back-door preference for Yanukovych over Tymoshenko. Yanukovych has had to build his own power base.

Yanukovych’s Ukraine does not have war as an excuse for centralizing power, as Putin did in 2000 – nor the claim to be restoring ‘great power’ status. In fact, the more general failure of Ukrainians to agree on a common external enemy means that foreign policy is never likely to be successful as a factor in creating unity out of domestic diversity.

The Ukrainian economy is not about to embark on a seven-year boom, and will not be able to provide the bread and circuses that Putin was able to provide from 2000-08 (for more on the economy, see below).

The Ukrainian oligarchy is more deeply embedded than in Russia. Oligarchs have more power over the state than the other way around, and that power has even grown in recent years. Putin’s indispensability in Russia is because of his role as “lord of the rings,” balancing the various clans. Kuchma’s system was the same in its heyday, as are many or even most post-Soviet states, like Azerbaijan under Aliyev or Armenia under Sargsyan. But Yanukovych is less powerful personally; he is only just first among equals. His short presidency to date has managed to suffer from both the ‘gas lobby’ being too dominant early on and then a more general feeding frenzy, with the Akhmetov group hovering up the domestic steel industry, including Mariupol Illich and 50 percent of Zaporizhstal. It is hard to imagine a Ukrainian Khodorkovsky – i.e. a major oligarch ending up in prison as an example to others. The Tymoshenko trial has been for largely political reasons.

The Ukrainian security services are not available as an alternative power-base for Yanukovych, as the FSB was for Putin. Ukraine’s siloviki are divided. If SBU head Valery Khoroshkovsky succeeds in his empire-building, this opinion might have to be revised; but at the moment his power seems to derive from his links to private business and TV (Inter), rather than the other way around. Moreover, Khoroshkovsky pursues his own interests, not even Yanukovych’s. More generally, the law enforcement agencies – the SBU, the Procuracy, the customs, the Interior Ministry, the prisons – are ranged against one another after competitive state capture by various oligarchic groups. Most are also internally divided.

The central state is therefore much weaker in Ukraine than in Russia. This is also because Kiev’s starting point in 1991 was radically different from Moscow’s, with many institutions having to be built from scratch. Kiev is also a relatively small capital, always in rivalry with Donetsk, Kharkiv, Odessa, Lviv and Dnipropetrovsk, lacking the demographic, financial and political predominance that Moscow has in Russia.

The level of political opposition is higher in Ukraine in 2010-11 than it was in Russia in 2000. It is in decline, particularly since the late orange years, but still benefits from the upswing in 2001-4. Tymoshenko has not yet been destroyed (or coopted) as an opposition force. Civil society activism also declined in the orange years, but more recently the ‘tax maidan’ protests at the end of 2010 showed the emergence of new SME lobbies alongside traditional strengths in election monitoring, youth groups and a vibrant and pluralistic religious sector.

But civil society is only relatively stronger than in Russia, and not as strong as in central Europe. Paul D’Anieri argues that Ukraine has both a weak society and a weak state. One of the most depressing trends in recent years has been the rise of virtual activism. Pensioners have long been paid to stand in the snow; now they are joined by student entrepreneurs who will bring out their whole dorm as a crowd for hire.

Ukrainian and Russian politics used to be corrupted in similar ways by so-called ‘political technology,’ but their paths have diverged since 2004. Russia now has problems of over-control: whereas certain types of political technology became more difficult to use in Ukraine in 2005-10, most notably blatant voting fraud and ‘project’ parties that often withered under the scrutiny of a freer media. But other types of ‘political technology’ never really went away. ‘Soft’ administrative resources (i.e. not actual ballot-stuffing, but state patronage and directed voting of ‘controlled populations’ like the army or prisoners) and ‘kompromat wars’ were always most deeply embedded in the system. And since February 2010 the cruder types of manipulation like fake parties and state-funded ‘loyal oppositions’ have started to make a comeback as well.

Ukraine’s lively mass media also acts as a constraint, but again possibly of declining strength. There was a cultural revolution among some journalists in 2004, but the venality and self-censorship of most is a systemic weak-point. Another is that even in 2005-10 the mass media was more pluralistic than it was free. The press and TV largely escaped from state control but not from the dictates of oligarchical owners. As in Russia in 2000, direct censorship is initially unnecessary. The state can restore control by pressing for changes in ownership or threatening owners’ other business interests. The Ukrainian internet in 2011, however, is more developed than the Russian internet was in 2000.

One final contrast is in regime narrative. Putin’s entire ideology was based on trashing the 1990s. Yanukovych can and does attack the orange years in a similar fashion and many, both in Ukraine and abroad, at least initially excused too much in the name of ‘order’ after ‘chaos.’ But ‘order’ is not a long-term narrative in itself, and Ukraine under Yanukovych has so far failed to come up with anything else. There is no special ‘Ukrainian way’. The best that Yanukovych advisors like Andrii Yermolaev can come up with is airy talk of a vaguely less capitalist and uniquely Ukrainian path “between Karl Marx and Adam Smith.” China and other states have shown a path towards ‘authoritarian modernization’, but basic facts of geography and geopolitics mean an authoritarian Ukraine would be more isolated and less economically successful than China or Singapore, and less influential than rising BRIC democracies like South Africa or Brazil.

REGIONALISM

The most important factor in the “Ukraine is not Russia” thesis – Ukraine’s regional divides – deserves a section on its own, as regional divisions still color every aspect of Ukrainian life.

Ukraine has more than ten main regions: the poles of Galicia and the Donbas therefore command only about ten percent of the population apiece. One can predict with short-term confidence that the Galician ten percent will not come to power on its own. Long-term frustration at being denied their European ‘birthright’ will therefore lead to periodic flarings of local patriotism, and not always in the multi-ethnic Galicia felix variant. ‘Bandera politics’, the symbolism of the OUN-UPA era, has if anything become more salient in the 2010s than it was in the perestroika era. In part, this is because the third myth, namely Mykhailo Hrushevsky’s idea of Galicia as the ‘Ukrainian Piedmont’, has taken a battering since 1991. Galicia has been unable to proselytize its version of Ukrainian identity. Lviv was never exactly a financial powerhouse like Milan; and the idea of the Galician Piedmontese lording it over the rest of the country has certainly never come to pass. The one part of the Galician myth that remains strong, however, is the idea of preserving the flame of true Ukrainian identity for the rest of the nation; which acts as a constraint on the development of the alternative myth of ‘gosudarstvo UkraХna’ (the state of Ukraine) – the idea often propagated by intellectuals close to the magazine Ї that the rest of Ukraine is really just Russia-lite. Though periodic flirting with the idea of a smaller and more manageable Ukraine remains likely – under Yanukovych demonstrators in Lviv have carried signs with ‘Independence for the Donbas!’ written in Russian.

The Donetsk ten percent, on the other hand, has come to power, in fact on four separate occasions: first in 1993-4 under Yukhym Zviahilsky, then in 2002-4, 2006-7 and 2010 onwards under Yanukovych. So what’s the difference? Despite the coming of age of south-east Ukraine in 2004, it is still difficult to mobilize the entire population from Sumy to Odessa on amorphous identity grounds; which is one reason why the Russian language issue is prominent when it is politicized from above at election times, but then fades when it needs to be sustained by civic activism in between. The more “national” half of Ukraine also has an amorphous general identity, but the grand arc of southern and eastern Ukraine is more amenable to coalition-building based on local business groups. The more “national” half cannot do this as there are no real business clans in central Ukraine west of the Dnieper.

But there is a downside: when the Donbas clans bring their thuggish political culture to Kiev, the end result is never good. Elite unity is a precondition for maintaining oligarchic politics in Ukraine. Conflict between the Donbas and Dnipropetrovsk dominated the mid-1990s. The Donetsk elite grew too greedy when Yanukovych was Prime Minister in 2002-04, helping spark the Orange Revolution. And there have been signs of this happening again since February 2010.

Regional factors still dominate Ukrainian elections. Three-quarters of the population supports independence, but Ukraine’s well-known electoral divide has been closer to fifty-fifty in every election since 2004. This rough balance is not set in stone – the fact that the current electoral border follows in part the boundary of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth is historically interesting but contingent. Elections in the early 1990s were more like Galicia (and Kiev) versus the rest. The 1994 election drew yet another line on the river Dnieper. Kuchma’s re-election in 1999 drew atypical lines, because it was an election distorted by political technology.

The more “national” side consistently lost elections in the 1990s: the story of the relatively even contests in 2004, 2006, 2007 and 2010 is therefore also a story of how the more “national” side managed to expand its electoral base from 2002 to 2004 – and of how it got so far, but no further. Two tentative hypotheses would be that the gains in central Ukraine seem to have been due to a solidifying of national identity amongst rural and small-town Ukrainophones, and to the declining quasi-feudal power of Soviet collective farming and agri-business in the countryside. This process was accelerated by the 2000 agricultural reforms, and ironically might gain pace after 2011 if the Party of Regions carries through a proposal to end the moratorium on land sales. Another key factor was Yushchenko’s pragmatic and values-based campaign in 2004 – a factor which he completely forgot once he was in office.

Although the 2010 elections showed each side encroaching on the other’s territory a little, no one has been able to successfully bridge regional divides since 2004. Yushchenko forgot about the east once he was in office. Tymoshenko failed to become “mother of the nation,” in large part because of the strains of incumbency during such an intense economic crisis. Regionalism also remains the biggest obstacle to the Party of Regions building a one-party state. The October 2010 elections established Regions’ dominance in Crimea: 80 (originally 48) seats in the main Crimean council compared to six for the Russian parties, and 74.5 percent of deputies at all levels. And now that Serhiy Tihipko’s Strong Ukraine has agreed to a merger with Regions, they only face token opposition from the Communists in the east. But they will always meet resistance in the west and center-west, unless they can use patronage and administrative resources to push back the gains the other side made in 2002-04.

UKRAINE’S ACHILLES HEEL

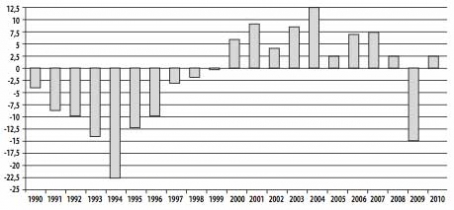

The economy is Ukraine’s Achilles’ heel. It has always under-performed. Policy errors made the post-Soviet recession much deeper than it should have been in 1992-4, and in the late 1990s prevented recovery from beginning as early as in Russia (1997) or Belarus (1996), with Ukraine’s first year of positive growth only coming in 2000. Even in the good years from 2000 to 2007, growth was never at BRIC levels. Only twice did GDP growth top 7.5 percent, in 2001 and 2003; not counting the stoking of the fires in the election year of 2004, after which the economy took a year out in 2005. Recent recoveries, both in 2006-07 and in 2010-11, have been relatively weak, certainly compared to the Baltic States’ bounce-back after 2008-09.

Table: Annual Change in Ukrainian GDP, 1990-2010

Source: Wikipedia

This economic under-performance is mainly the result of politics. Firstly and most obviously, because of ingrained post-Soviet corruption and because Ukraine settled into an unhealthy equilibrium as a semi-reformed oligarchic state in the late 1990s. Second, one of the huge disadvantages of Ukraine’s ‘pluralism by default’ is that there has never been a united reform government with a clear program and mandate. Incomplete macroeconomic reforms in 1994-5 brought Ukraine back from the brink of economic disaster – but only just. The Yushchenko government closed down some types of rent-seeking in 2000, but again its reforms were incomplete. One of the biggest disappointments of the Orange Revolution was that successive governments failed to enact any serious broad program of reforms, despite piecemeal improvements. The first Tymoshenko government (2005) was populist; the “business-friendly” Yekhanurov government (2005-06) was essentially a holding operation. Yanukovych (2006-07) restored Azarovshchina – the use of administrative resources to reward friends and punish opponents (named after the then Finance Minister and now Prime Minister under Yanukovych). Tymoshenko took office for a second time (late 2007 to early 2010) just as the global economic crisis was about to hit.

So Ukraine is stuck with oligarchic rent-seeking. Ukraine joined the WTO in 2008, but, pace Anders Бslund, Ukraine has a long way to go to “become a market economy.” Despite occasional hype about learning from Georgia’s success in public sector reform, Ukraine is really the anti-Georgia. Azarov’s people are fundamentally suspicious of any economic activity they do not control. Only 15 percent of GDP is generated by SMEs; Ukraine is 145th of 183 in the global Ease of Doing Business survey (even Belarus is 68th).

A further problem is that Ukraine has no resource economy, but it has energy transit, and therefore arguably the worst of both worlds. Countries like Moldova have no big strategic prize to corrupt politics. Ukraine, on the one hand, has enough to feed elite corruption. Margarita Balmaceda has argued that the sheer amount of money involved in gas corruption was enough to trump even the best of intentions (which weren’t always there), and was the single most important factor derailing the Orange Revolution. But, on the other hand, there isn’t enough rent in Ukraine to fund a Putinist social contract, or even a Belarusian version like Lukashenka’s, paid for with Russian money.

NOT A CENTER NOR A MAJOR POWER

Another clichО that contains important truths is that Ukrainian foreign policy is multi-vectoral – and according to some must always be so. But the same can also be said of most CIS states (the Baltic States having made their choice): Belarusian foreign policy has had several ‘wings’ since 2006, even Russia-first Armenia has “complementarity,” and Russian foreign policy itself is formally multi-vectoral.

So clearly the clichО means different things. For Russia, it means that Russia sees itself as a great power sharing the world with, and having equal relations with, other great powers. Russia sees itself as a pole in a multi-polar, or ‘multi-unipolar’, world, so its vectors are both long links to the other poles and short links to satellite or friendly states.

Ukraine is not a great power, and is certainly not a pole. It has no satellites; it doesn’t even get on with, or even understand, tiny Moldova. A second possibility that has become fashionable under Yanukovych is to compare Ukraine with Turkey. Ukraine would also like to see itself as a big power on the edge of Europe, interacting with the EU from a position of strength. But Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu defines national foreign policy not by multi-vectorism but by ‘strategic depth’, with Turkey as a ‘pivotal country’ (merkez Яlke) at the center-point of concentric power circles based on overlapping historical spheres of interest, including Turkophone, neo-Ottoman and business ties. Which, to labor the point once again, Ukraine does not have.

Nor is Ukraine riding high like Turkey after a decade of double-digit growth. Nor is Ukraine a ‘BRIC’. In fact, it is intensely vulnerable to a double-dip recession, and once again needs the IMF after being in and out of IMF programs for longer than most other post-Soviet states (1994-2001, 2008-09, 2010, 2011 plus). Nor does Ukraine have the kind of get-out-of-jail cards that grant Russia (nuclear weapons, energy) or Turkey (it’s role in the Middle East or as a beacon for new Arab democracies) more freedom of maneuver. The Yanukovych administration has tried to play its deal with the U.S. to eliminate all its enriched uranium by March 2012 in this way; providing a trading card that has produced the promise of $60 million in U.S. aid, but not a trump card.

Ukraine has only briefly had a ‘brand’ to sell, exploiting its role as a beacon of democracy between 2005 and 2009 (by 2010 largely dissipated by ‘Ukraine fatigue’). Ukraine has also periodically played indirect foreign policy strategies, sending troops to Iraq to curry U.S. favor rather than serve any direct national interest (and also to try and rehabilitate Kuchma after the Gongadze and Kolchuha affairs). Ukraine has tried to play up its role in the northern corridor to Afghanistan, via railways and strategic air lift (before scheduled withdrawal in 2014). But ultimately Ukraine is not Uzbekistan, with whom the U.S. is considering a strategic reconciliation before 2014.

Nor is Ukraine like Belarus or Azerbaijan. Energy-rich Azerbaijan can exploit eager international investors to win itself foreign policy freedom – which is not an option for Ukraine. Belarus under Lukashenka has the opposite policy, pioneering a rent-seeking foreign policy using various forms of blackmail and repositioning threats. After 2004, Lukashenka also successfully sold himself to Moscow as a bulwark against ‘colored revolution’. As a result, Minsk earned rents that were approaching 40 percent of GDP at their peak in the late 2000s. Ukraine has most in common with this rent-seeking model, but that has traditionally been much more dependent on Ukraine’s position as an energy transit state.

China’s new role in Eastern Europe gives Ukraine more wriggle room, as does a weak and introspective EU, a distracted U.S. and a more mercantilist Russia. And, as in Africa, China’s engagement is free from the irksome conditionality preferred by the West. But ultimately Ukraine has the multi-vectoral foreign policy of a small state. As small states have often done, it alternates between seeking to isolate itself from the pressures of its larger neighbors and bandwagoning with one against the other. But after twenty years, Ukraine’s room for maneuver is narrowing. Basic facts of geography, history and Ukraine’s complicated internal regional and identity politics will always mean Ukraine will maintain ties with both Europe and Russia. Some types of balancing can maintain simultaneous coexistence more easily than others, such as freer movement and people-to-people contacts with both east and west. But in the longer term, Ukraine has to decide how much balancing its foreign policy can cope with. Its partners are demanding a more genuine partnership. Since 2004 an expanded EU and NATO have both bordered Ukraine. A DCFTA (Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement between Ukraine and the EU) that involves swallowing and slowly implementing a good chunk of the EU rule book, the acquis communautaire, is incompatible with Russia’s proposed Customs Union, even if Russia is also taking on parts of the acquis. Russia, on the other hand, has a more toughly pragmatic neighborhood policy, and seems likely to push the Customs Union regardless as the key foreign policy theme of Putin’s third term.

* * *

Ukraine is always said to be at a “crossroads.” It has so many existential dilemmas of national identity and foreign policy direction. But this time its partners are demanding answers and its options really are narrowing. It is in danger of becoming a dysfunctional semi-autocracy and a double periphery rather than a mutual neighborhood. Modern Ukraine gained its independence twenty years ago in 1991 – it is therefore older than eighteen though less than twenty one. Ukraine is no longer an adolescent and should be setting out its own path in the world.