One can endlessly redraw the global energy map and rearrange key players on it while firmly believing in the enormous potential of unconventional hydrocarbons, as our American counterparts do, but a sincere belief alone would not be enough to bring about serious changes into the world energy market. However, it would be more than enough to convince the audience whose hopes for new and – most importantly – cheap energy resources render it incapable of making a sober assessment of reality. We have been witnesses to this information thrust from overseas over the past five years, as it is vividly evidenced by an article America’s Energy Edge: The Geopolitical Consequences of the Shale Revolution by two American authors Robert D. Blackwill and Meghan L. O’Sullivan. The ideologists of a shale oil and gas revolution remain true to themselves – the audience needs to be constantly reminded that the global energy sector is no longer what it used to be five years ago and that its main actor now is the United States.

While agreeing that the energy sector is changing, we suggest taking a somber and calm look at the actual state of affairs in the field of unconventional hydrocarbon production in the United States using ample material available for analysis.

A MOST SUCCESSFUL PR CAMPAIGN

The first serious “information shot” alleging that humankind had all of a sudden become richer by 456 trillion cubic meters of shale gas was fired in 2009 after the publication of a new International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook 2009. Only the most fastidious readers tracked down the original source of these incredible data that more than doubled the world proven gas reserves at that time. In a short university almanac article in 1997 its author Hans-Holger Rogner, an honest man, made an honest conclusion based on his office calculations of conventional and unconventional hydrocarbon resources in the world: these data should be regarded as hypothetical and speculative and must be understood as such, especially in terms of regional assessments.

The author’s comment is absent from the IEA report, even though the word “speculative” will be crucial for the subsequent information campaign surrounding shale gas and then oil. In 2009, the IEA assigned 16 trillion cubic meters of shale gas to energy-scarce Europe and 100 trillion cubic meters to Central Asia and China. But there is more to this. In April 2011, a major survey entitled “World Shale Gas Resources: An Initial Assessment of 14 Regions Outside the United States” with detailed calculations for 32 countries was published under the auspices of the Energy Information Administration (EIA). It had increased the estimated shale gas reserves by 57% from the previous figure and gave Europe over 70 trillion cubic meters. No country except the United States had exploratory drilling results at that time and the data were once again obtained from open sources and simple arithmetic calculations. However, no one seemed to be surprised by this method again.

In April 2013, EIA added shale oil to their assessments of shale gas and enlarged the number of countries to 41. The magical figures for gas were toned down after recalculation of resources to 207 trillion cubic meters of technically recoverable resources plus 345 billion barrels of unconventional oil. So the PR campaign kept evolving by the rules of the genre and the topic of gas was supplemented with the export of cheap American LNG and the topic of oil with subsequent export to world markets.

The shale oil situation appeared to be even more confusing than the shale gas one. This term first appeared in the WEO2010 report of the International Energy Agency. Its authors had classified shale oil as only synthetic oil obtained from kerogen (not the light tight oil that was already produced at the American Bakken play at that time), noting in passing that the oil extracted in shale formations using hydraulic fracturing should be considered conventional oil. Technically recoverable resources of kerogen oil were estimated at 1,000 billion barrels in the U.S. alone vs 1,600 billion barrels of global proven reserves. After several years of confusion, the international community came to the conclusion that kerogen oil was a matter of distant future despite its enormous potential and that the main factor that would drive the world oil market was Light Tight Oil (LTO), the production map of which was identical to that of shale gas and was confined mainly to the United States and Canada.

The efforts undertaken by the U.S. Energy Information Administration and the International Energy Agency and picked up by mass media and endless debates going beyond industry discussions resulted in the worldwide shale fever that engulfed Europe, China, Australia, India, Latin America, Algeria and the rest of the world. The unique result was achieved in a short time and practically at no cost, marking the world’s most successful PR campaign. It should be added that the feverish search for new energy resources gave American companies practically an unlimited market for their shale gas and LTO drilling services. Currently 80% of specialized onshore drilling services are provided in the United States. But this is just a side effect, while the main goal is much more ambitious.

AMERICAN REALITIES

Commercial shale hydrocarbon production started in the United States only six to seven years ago, which is a very short period for the development of a new energy sector. And since shale gas production has so far not gone beyond the United States and Canada (except for pilot projects in China, Australia and some other countries), it becomes clear that one cannot yet assess its global scale and impact. And no matter how much “the greatest revolution” is trumpeted by its ideologists, it is still solely an American phenomenon.

An obvious and indisputable argument, which brought about the “shale hydrocarbon revolution,” was and still is the growth of shale gas production in the United States from 54 billion cubic meters in 2007 to 319 billion cubic meters in 2013. This increase in supply to the hitherto energy-deficient U.S. market has already changed the situation in the country, allowed it to reduce gas import from Mexico and Canada to the necessary minimum cross-border flow and change the structure of domestic consumption in favor of gas, thus spurring the development of energy-intensive industries, which improved the energy security of the region immensely.

The oil balance in the region has also changed considerably. LTO production had increased from virtually nonexistent in 2007 to 2.3 million barrels per day by 2013, allowing the United States to reverse the downward trend in domestic oil production and reduce import (except from Canada and Mexico) from 9.6 million barrels per day to 6.6 million barrels per day in 2012.

However, despite the overall increase in shale gas production in the country, its growth has been slowing down for a third year running. While record high at 48% in 2010, it dropped to 44% in 2011, to 22% in 2012 and to a mere 15% last year. The analysis of production by key fields shows that only the two newest of them – Marcellus and Eagle Ford – are showing strong positive dynamics, while Fayetteville and Woodford have almost stopped growing and the oldest Barnett and Haynesville fields are declining.

The easiest way to explain this is to cite an old argument used by the opponents of unconventional production that shale fields have a short life cycle. In fact, the productivity of new wells plummets in the first year and goes down almost to zero within the first three years, which requires new wells to be drilled in order to keep up production. The same is true of oil production.

However, two more explanations have to be mentioned for the sake of objectivity. Companies can intentionally curb production if the domestic market is oversaturated and prices are low but will increase it by the time export operations begin. Or the economics of shale gas under current low prices is such that operators are shifting attention to liquid hydrocarbons and reducing the number of new gas wells drilled. The next two to three years will show which of these explanations is correct, although all three may be true in part.

For that matter, the economic model of shale gas production is a separate topic as Americans’ statements that their gas “is the cheapest in the world” look too presumptuous. It’s hard to figure the truth because companies’ reports give no direct clues about the cost of the gas produced, official statistics even less so. Besides, the cost of gas varies from field to field, from well to well and from company to company. However all authoritative industry sources (IEA, BP, Bloomberg, OIES and WoodMac) are almost unanimous in that the average break-even price of dry shale gas in the United States is $150-200 per 1,000 cubic meters, which is several times the cost of conventional gas.

LTO projects break-even price is also quite impressive and ranges from $50 to $80 per barrel compared to $40-60 per barrel for deep-water offshore projects in Brazil and $35-40 per barrel for accessible conventional oil deposits in the Middle East. And while oil production is sustained by high crude oil prices, the gas market in North America operating under low prices is balanced by a number of unique factors such as shallow reservoirs, simultaneous production of gas and liquid hydrocarbons, developed infrastructure, legal regulations, closeness to consumers, a large number of companies seeking to minimize their costs and a deep financial market. And this is not a complete list of factors facilitating gas production in the United States.

And yet, with all the propitious conditions the industry is hardly prosperous. Experts note more and more of alarming signs, primarily fiscal ones. For example, a number of companies (Chesapeake, Devon, BP, BHP, Encana) have had to write off $35 billion worth of assets that have fallen short of expectations in recent years. A survey released by the Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy (EIA DOE) for 2012 revealed negative return of equity dynamics for companies working mainly with gas. Financial statements of many companies with shale oil and gas assets also show downward cash flow per share trends.

It should be noted that although oil production is growing, oil processes in the United States are tightly pegged to international markets due to considerable volumes of oil and petroleum product import, which keeps the prices in the region quite high. As the supply of “cheap” domestically produced oil increases, prices will go down, widening the price gap with other regions, which will inevitably result in revenue losses for American shale oil producers. Eventually these projects just like shale gas projects may not be so attractive for investors and producing companies after all.

Sober-minded analysts do not question the existence of shale oil and gas production as such but call for thorough analysis, reasoning that oil and gas so extracted may be too costly. This is the overall message of one of the latest works entitled “U.S. Shale Gas and Tight Oil Industry Performance: Challenges and Opportunities” released in March 2014 by the authoritative Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES).

There is yet another opinion circulating among experts that seems to describe American shale paradoxes quite accurately. The oversupply of gas that has caused prices to take a sharp dive in the United States will undoubtedly benefit consumers but will obviously hurt extractive companies and will inevitably lead to a revision of this temporary and shaky model.

Let me now add a few words about environmental aspects, which will raise legitimate concerns associated with shale oil and gas production. Relatively shallow shale formations in North America is an obvious advantage as they help reduce production costs, but there is the other side of the coin too. No matter what companies say in a bid to calm down the general public, their operations are carried out near water-bearing beds. According to American expert Arthur Berman, the upper border of the largest Marcellus play begins at a 400 foot mark, the level where drinking water-bearing strata lie.

Environmental issues in this case are the prerogative of the national government and people. If they like to see huge abandoned production areas which look more like a pasture ground for overgrown moles, it’s their choice. If they have got accustomed to seeing large lagoons filled with used drilling fluids, quite hazardous as the warning signs on the fence say quite explicitly, it’s also their choice. Plus the reluctance to realize that after evaporation under the sun and wind these fluids will come down on their heads with the first rain. And if environmental requirements are tightened, the price of hydrocarbons so extracted will inevitably grow. It is hard to imagine that the majority of people in America dream about turning a good part of their country into such lagoons, which will certainly happen if ambitious and long-term shale oil and gas production and export plans get underway. Just a look at the map of the United States would be enough to see that the oil and gas-bearing plays make up a half of the country’s territory.

THE SCALE AND COST OF AMERICAN EXPANSION

Faced with the oversupply of gas on the market, producing companies found an obvious solution by offering to export it as LNG, and this coincided in time with the lowest prices of $70 per 1,000 cubic meters ($2/MBTU) in the first half of 2012. The sale of such cheap LNG on the expensive Asian markets promised a margin of $200 per 1,000 cubic meters, according to Cheniere Energy data. Supplies to Europe looked less lucrative at $150, while the biggest profit of nearly $300 per 1,000 cubic meters could have been reaped in Latin America due to low transportation costs and high prices. Seeking to count every cent, each extractive company made similar calculations, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission was flooded with applications for export licenses.

However, as time passed, the glaring gap between production costs and selling prices was narrowing, forcing the average price at the key U.S. Henry Hub to virtually double from the giveaway level in April 2012 to about $130 per 1,000 cubic meters in 2013. So, as the cost of feedstock rose, so did the mercantile estimates of potential exporters, with their margin going down to $140 for Asia and to $104 for Europe but staying quite high at $230 in Latin America, according to Cheniere’s data effective as of February of this year. The estimates are as simple as they are clear: American LNG will bring the biggest revenue if sold in Latin America and Asia while supplies to Europe are questionable for economic reasons.

The second conclusion, just as obvious, is that American companies, which have been operating under strained market conditions for years and which have sustained huge costs incurred by the refitting of old and abandoned LNG terminals into LNG production facilities, will be least inclined to sell at dumping prices on robust markets. It would be logical to assume that they will most likely seek to derive maximum profits after a long period of abstention. Only political will can force companies to sell gas, produced and delivered at such a high cost, at below-market prices. But in this case one should forget the second most loved American word after democracy – “market”. If export does not bring expected profits to companies, there will be no one else to salvage shale hydrocarbon production projects.

All forecasts suggest that Henry Hub’s internal price will rise to $6/MBTU by 2016-18 from $4 now, thus reducing potential income from exports to Europe virtually to zero. There has been no word about the creation of a specialized tanker fleet for these supplies, and it will take a long time to build it. Besides, there is a strong anti-export lobby in the United States – industrialists, energy sector companies and environmentalists are doing their best to reduce possible exports in a bid to save the fuel for themselves or ban its production altogether.

Speaking of export, it should be noted one more time that the production of shale gas as such is surrounded by a veil of uncertainty: by 2016 its volumes may not be sufficient for export or its production cost could be too high. Therefore, the second round of the shale hydrocarbon revolution based on expectations of large volumes of cheap North American LNG is no more than an ideologeme for the time being. Major European and Asian consumers are being given an argument for dialogue with traditional suppliers, which in reality may turn out to be a phony. Certainly some amounts of American LNG will appear on the market but they will be way below the declared levels and certainly not cheap.

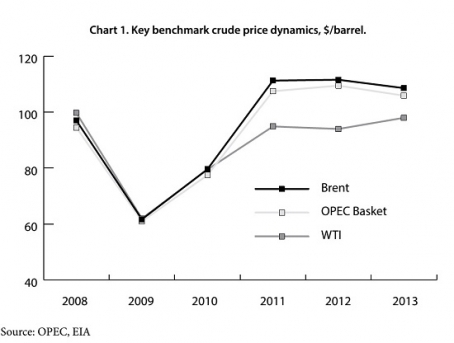

The oil market lives by its own laws just due to its global nature and is in fact much somber and calmer than the Americans think. Shale oil production costs in North America are quite high. Additional shale oil production volumes are estimated at $200-300 million tons by 2035-2040 (projections vary too much), and even if one assumes that all these amounts are exported, which is unlikely given domestic needs, this amount of North American oil and its production capacities will still not be enough to affect world prices. Oil production in North America in 2008-2012 increased by more than 100 million tons, but there was no decrease in world prices over the same period (see the chart below).

Moreover, a dramatic fall of prices can hardly benefit the United States where the oil industry can be more or less profitable if the price of oil stays above $90 per barrel. If prices go below this level, companies will not be able to produce shale oil or bituminous sand oil or most of the offshore oil in the Chukchi Sea and the Gulf of Mexico or high viscosity oil, let alone biofuel…

This said, all attempts to redraw the global energy map seem to be all the more senseless. True, some changes can occur on the market with the emergence of a new source, but one player with limited possibilities, obscure prospects and certainly not cheap resources cannot have any significant impact on the global market. This explains why overseas politicians are in such a hurry to play this card. They are running out of time in trying to rock the situation by pushing traditional suppliers away. When the situation becomes clearer in a couple of years, the target audience will recollect itself.

NO SHALE HYDROCARBONS BEYOND THE SEAS YET

The amazing credulity of energy-deficient regions regarding generous promises of shale hydrocarbons can be understood. How can one not believe the good news amid constant dependence on external supplies? Actually, the price Europe and China have paid for testing their credulity is not so high – in fact, they need to understand what kind of subsoil resources they really have.

Poland is an example of how the shale hydrocarbon revolution is evolving outside the United States. The country started exploring for shale gas immediately after the IEA had released its first assessments of shale gas reserves in Poland, putting them at over 5 trillion cubic meters. In March 2012, the Polish Geological Institute and the U.S. Geological Survey reassessed Poland’s recoverable shale gas resources to 550 billion cubic meters, cutting the previous estimates more than 10 times. Since the start of intensive exploration in Poland, where more than 100 licenses have been issued and 50 exploratory wells drilled, only one produced a daily commercial flow of 8,000 cubic meters. There is still hope, but major companies have already wound down their operations. And it should be added that from the geological point of view, Ukrainian shale oil deposits are an extension of the Polish ones.

With four wells drilled by the end of 2013, Great Britain is the only country that has a more or less official forecast for shale gas production made by the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG): 1 billion cubic meters by 2020 and 2 billion cubic meters by 2022. Small as they are, these volumes will not go beyond the country and therefore will have no impact on the European market.

It seems that Europeans have already come to understand that their hopes for own shale gas will never come true and what little can be discovered will be much more expensive than the American supplies. But why was it necessary to spoil relations with traditional suppliers amid this unfounded shale hydrocarbons euphoria? China has been acting much more prudently in this respect: it is exploring for both shale gas and shale oil, while continuing hydrocarbon imports, conducting negotiations and getting its companies into production projects around the world.

Europe, however, acted as a capricious girl who has got tired of all her boyfriends as soon as she saw a new smart-looking guy. But smart dressers are known to be light-headed and unreliable; they make promises but then vanish without a trace, leaving the girl fallen out with her previous suitors.

Europe has adopted the Third Energy Package, which has become a real sore spot for external suppliers. Europe insists that supplies be pegged to spot transactions which in large volumes run counter to the very nature of the gas business based on long-term projects and contracts. The European authorities have searched Gazprom’s offices and are resisting new Russian pipeline projects in every possible way. In their bid to cut the prices, European consumers over the past two years have lost almost a half of LNG supplies from 65 million tons in 2011 to 33.8 million tons in 2013. LNG exporters supply whatever gas they can to the insatiable Asian market. And the more nickel-and-dimed Europeans are, the sooner they lose the remaining LNG contracts.

It is high time Europe came to its senses, but it suddenly gets a letter from that same smart guy who assures it that there is no reason to worry as cheap LNG will soon come pouring in from North America. But as we have said above, Europe is a low-priority destination for the American gas which will go there only if the U.S. government shows the political will to support its European allies. This is borne out by our present-day opponents’ advice that LNG export should be allowed primarily to those countries where it can help to counter pressure from Russia or other suppliers.

Another region that is actively exploring for shale gas is China, which has hurried to include the prospective production volume of 6.5 billion cubic meters in its current fire-year plan. Beijing has done its best to succeed by engaging foreign companies, organizing tenders and introducing payment discounts for each cubic meter of extracted shale gas. There is no accurate information on the number of wells drilled. In 2013, China produced 0.2 billion cubic meters of shale gas. Its price has not been disclosed. The results of exploratory drilling indicate that the geological and physical properties of Chinese shale gas differ from those in the United States. This does not mean that shale gas production is impossible, but its cost will be different. In addition, there is still no technology that would allow commercial production of shale gas without water which is a critical commodity in China. It is already clear that shale gas that can potentially be produced in China will stay on the domestic market.

There have been short reports about successful shale gas tests in Australia, Argentina and Algeria, but they have not been confirmed and things have not gone any further than that. China and Australia have begun searching for shale oil; Morocco, Argentina and even Israel have made some bold statements, but it is too early to speak about concrete results.

THERE IS NO ENERGY WITHOUT POLITICS

There can naturally be no energy without politics, but there is only politics and no energy whatsoever in the American authors’ article “America’s Energy Edge”. If the geopolitical constructions led by the United States and weak OPEC and Russia they described are cleared of the shaky energy basis, that is, the shale hydrocarbon revolution, the consequences of which are quite unpredictable, there will only be sheer politics left. What goals is the United States pursuing as seen by former officials from the George Bush administration? Only one of the goals they declared can be called politically neutral and generally positive, and that is to deal with climate change by increasing the use of natural gas. There can be no objection to that.

But that’s where revelations begin and they must be cited:

“…the newly unlocked energy is set to boost the U.S. economy and grant Washington newfound leverage around the world. … Countries that like to use their energy supplies for foreign policy purposes – usually in ways that run counter to U.S. interests – will see their influence shrink…

“Of all the governments likely to be hit hard, Moscow has the most to lose. … Russian President Vladimir Putin’s influence could diminish, creating new openings for his political opponents at home and making Moscow look weak abroad…

“The huge boom in U.S. oil and gas production, combined with the country’s other enduring sources of military, economic, and cultural strength, should enhance U.S. global leadership in the years to come.”

It is all said so straightforwardly and frankly that comments would be unnecessary. But let us be just as frank. All ideological reflections on energy made by American political scientists reveal the same key approaches as in the overall policy and the same double standards whereby major hydrocarbon exporting states are strongly criticized for using energy as a foreign policy tool. This was the main complaint against Gazprom on the CIS and European markets. But as soon as it gets a chance (no matter real or imaginary) to obtain a similar tool, Washington will never let it go and will use it to its utmost.

The second approach, which is especially relevant in light of the latest developments, is the obvious desire to create controlled chaos in one of the most sensitive fields – the global energy sector – and shake the positions of traditional suppliers, thus destroying long-standing ties and creating real risks for both energy suppliers and consumers. What else can this be other than chaos which the United States is going to control as the principal? There is no need to worry for Russia and the budgets of the OPEC countries as they survived the oil price plunge in 2009 and the Asian crises in the late 1990s, but what is going to happen to Europe which is facing, not without the U.S. influence, the risk of gas deficit and weaknesses in its energy balance? The next in line is Japan which, being hypnotized by future cheap supplies from North America, is starting discussions with suppliers and contemplating a transition to spot trading which has never existed in Asia before. There is no need to explain how critical such transformations can be for that country which is so vulnerable in terms of energy. But this hardly bothers the United States lured by the pursuit for global dominance not only in the economic or military field but also in the energy sector.

P.S. On March 26, 2014, at the U.S.-EU Summit in Brussels, Barack Obama assured EU leaders that Europe would get as much American gas as it needed.