The global community is reconfiguring into a new hierarchy of powers, whose voice cannot be ignored in addressing international issues. The previous setup took shape after World War II and existed in a “bipolar world,” in which the poles – the Soviet Union and the United States – grouped around themselves their allies and close or distant satellites from non-aligned states.

The economic potential in that system of relations was a crucial pre-requisite for military and political might. At the same time, there was a striking disproportion between the nuclear parity, achieved by the Soviet Union and the U.S. by the early 1980s, and a wide gap between the Soviet and U.S. economies (increased still more by the aggregate economic weight of U.S. allies in Europe and Japan). The ongoing globalization is only enhancing the significance of economic might as the key factor of influence. It is also increasingly eroding institutions and ideological patterns of the previous era.

THE POST-BIPOLAR WORLD: QUESTIONS AWAITING ANSWERS

The bipolar model of relations, with its numerous modifications, had existed until the beginning of the 1990s, when the breakup of the Communist bloc and the Soviet Union predetermined the end of the Cold War. The next two decades were a transitional period, when it became clear that the U.S. aspirations to world domination and absolute leadership had not come alive.

Now the main criterion for being a “great power” is economic might per se, while military might is no longer a must. For example, leading economies, such as Japan or Germany, are not seeking to possess large armed forces. It is particularly characteristic of the rapidly growing new world powers: China, India and Brazil, although the latter countries have been conspicuously building up their regional military capabilities.

The top three world economic powers in terms of their share of gross domestic product in world GDP (calculated by purchasing power parity) include two Asian states: China (second place, with a 16-percent share in the world GDP, and Japan, just below 16 percent). The United States is first, with 24 percent. The share of the Russian economy is 3.5 to 4 percent by the most optimistic estimates.

World War II victors and losers alike are among the leading economic powers: countries of Europe, North America, Asia, Australia and Oceania. Consequently, the original UN Security Council membership, limited to a group of winner-states, increasingly looks as an anachronism.

The emerging new system of relations and the new hierarchy of international influence have raised questions that require urgent and unequivocal answers, crucial for the effectiveness of actions in the international arena. The following are some of the key questions:

Can the growing “split” in the economic reproduction cycle between developed and developing states end up as a new format of world “blocs”?

Can an individual country with a vast territory and a considerable economic potential develop successfully and build up its international influence without forging close alliances? How feasible would this way be for Russia? What underlies the present-day modernization of Russia?

Does the economic globalization make relations between sovereign states stable and efficient, or has the modern economy become groundwork for mounting chaos?

More questions will certainly be forthcoming shortly. Let us look for the answers to some of them.

RUSSIA AMID THE WORLD ECONOMIC CYCLE SPLIT

The globalization of the world economy withstood the test of the world crisis of 2007-2010. It did not break up into rival economic blocs. Nation states placed no restrictions on free movement of capitals in the world financial market, although it might have been expected, taking into account the fact that it was the financial crisis that wrecked the successful development of the world economy and caused its dramatic slump. The world economic cycle split, as the developed states plunged into recession, while only some countries – the leaders of the developing markets – maintained relatively rapid growth rates. Russia apparently does not belong to countries posting fast post-crisis economic growth.

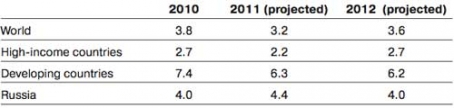

The World Bank’s 25th Russian Economic Report, out in June 2011, says that the world economy will slow down in the medium term. The post-crisis economic growth is estimated as moderate (see Table 1).

Table 1. GDP Growth, %

Stagnation would probably be a fitting description for the situation in the Russian economy. It has been posting slow growth, no positive structural changes, and low competitiveness of producers in international and even domestic markets. According to World Bank analysts, “Russian exporters face difficulties not only entering but also sustaining their presence in foreign markets.” “Only 57 percent of Russian export events (defined as one foreign sale in a given year) between 1999-08 survived after the initial two years. In China, for example, this rate is slightly higher than 70 percent. […] In Russia, the low export survival rates are, to a large extent, a symptom of the lack of competitiveness of the non-oil and gas sectors.”

In addition to the share in the world GDP, measured by PPP, a country’s place in global economic ties can also be defined by its share in world exports of certain groups of commodities and services and its balance of payments. Another criterion is the global competitiveness of an economy, which has been used as a generalizing synthetic indicator for the past two decades. Annual World Economic Forum reports can serve as an example of such evaluation (see Global Competitiveness Report 2010-2011). Switzerland has been ranking first in the past few years in the Global Competitiveness Index. The United States has gradually declined to the fourth position, while Russia is in the middle of the long list at 63rd place.

Meanwhile, international economic competition keeps growing. On the one hand, it is a struggle for goods and services markets; and on the other, it is a rivalry for investment. This context is also manifesting yet another distinct pattern. Rapid economic growth is characteristic of economies catering not only for consumers abroad but also for the domestic market. The huge domestic markets of Asian countries, with their rapidly growing population, give them a tremendous competitive advantage and are a growth driver.

In the past two decades, emerging market economies have been building their human capital by sending large numbers of their citizens to study in the United States, Great Britain and EU countries. It is the consumption of modern higher education services by students from India and China that made up the backbone of a large middle class in these countries. This became possible as incomes of both households and the governments of developing states began to grow.

The split of the economic cycle was a major setback for export expansion plans of countries that produce mass industrial products and exporters of raw materials. Of course, they are stepping up cooperation with each other, being mutual markets for each other’s products. Simultaneously, competition in all world markets is intensifying dramatically, including the market of long-term direct investments. Modernizing the Russian economy without attracting this capital would be absolutely unfeasible.

The economic growth forecast for Russia at 4 to 4.5 percent a year for the next few years is obviously insufficient for cutting the lag in economic development between Russia and developed or rapidly developing states. Russia’s oil and gas producing sectors account for more than half of its budget revenue. It comes from operations in foreign markets with the countries which remain Russia’s potential opponents due to its existing military might.

The banking system and financial markets are insufficient to serve the domestic economy in the present post-crisis period. Large corporations and banks have to keep borrowing from foreign markets. Enterprises are inefficient in using their fixed assets and financial resources. Labor productivity is low in industry and the services sector, both private and state-owned, making up only 30 percent of the U.S. figure.

As the country was pulling out of the crisis, there was no “reappraisal of values” in the economy, accounting or macroeconomics-wise. The economic system has retained its pre-crisis structure; natural resources continue to be used inefficiently; and labor productivity has not increased. The investment climate in Russia is universally acknowledged as unfavorable; hence the slow recovery in production.

The Russian economy continues to heavily depend on the volatility of oil prices. If they fall, its finance will immediately find itself in hard times. The current account surplus will move into deficit; the ruble rate will fall against major currencies; the federal budget deficit will increase dramatically; and banks and large industrial companies will encounter considerable difficulties in servicing foreign corporate debt.

In early 2011, investments in the Russian economy grew very slowly and were mostly concentrated in the traditional export-oriented sectors – metallurgy and hydrocarbon fuel production. Foreign direct investment is under tough government control. Under Russian laws, a potential foreign investor in any of 42 “strategic” sectors of the Russian economy must have preliminary approval from a government commission for his participation in an investment project, if his contribution exceeds 10 percent.

For example, in attracting investments from foreign car makers, the Russian Ministry of Economic Development has implemented a flexible plan combining tax and customs incentives with a requirement to localize the production of components for end products. However, further requirements to transfer technologies and licenses to Russian partners without reciprocal tax and land lease concessions are unacceptable for investors.

In these conditions, it is important for investors to evaluate country risks in Russia and the performance of its legal and economic institutions. In the next few years, economic growth will increasingly depend on the domestic situation. It requires that the government and business concentrate on the efficiency of Russian institutions of economic and social development.

Negative factors that impede investment include the venal “administrative rent,” excessively bureaucratic procedures for registering new businesses, inherent risks in the law-enforcement and judicial systems, and an uncompetitive, highly monopolized system of Russian markets. The latter implies hidden cartel agreements on commodity markets and disproportionate influence of natural monopolies on economic development, which makes efforts to boost aggregate demand in Russia inefficient for stimulating economic growth.

A general liberalization of conditions for attracting foreign investors, together with incentives for those who want to invest in high-risk high-tech industries would be a most logical and effective approach towards overcoming Russia’s economic problems.

The stabilization of economic growth and revenue in the first decade of the 21st century did not lay the groundwork for long-term development. The global financial and economic crisis has dispelled the feeling of success and exposed the strong and weak points of the Russian economy and politics. Again Russia has found itself among similar emerging market economies facing similar problems. It has a growing feeling of going in circles, developing in cycles and progressing very slowly.

Russia’s economic slowdown has had serious negative consequences: first, it is lagging increasingly behind the West, occasionally referred to as “the Golden Billion.” Per capita GDP at 13,000 to 14,000 U.S. dollars puts Russia on a par with stagnating Latin American economies, without any prospects for elevation to a higher group.

Second, the economic slowdown does not meet the political or social expectations of the larger part of the Russian people, who continue to believe in Russia’s destiny as a great power, regardless of what they read into this notion.

Third, along with the habitual lagging behind the West, Russia may develop a habit of lagging behind Southeast Asian countries that used to be poorer than Russia. While the Russian public grudgingly acknowledges China’s lead in GDP, a prospect of sliding to Indonesia’s or the Philippines’ level would be extremely painful for it.

In effect, Russia has dropped out of the group of fast-growing economies and quit “the BRIC league,” at least economically. Earlier, too, Russia’s belonging to it was quite formal, as the structure of the Russian economy differs fundamentally from that of China or India. The economies of these countries are undergoing a transformation from agrarian to industrial, whereas Russia passed this development stage more than five decades ago.

The Russian authorities have succeeded in easing the consequences of the economic and financial crisis of 2008-2009 for the population. At the same time, the crisis-related fall of GDP and industrial production in particular, the suspension of bank crediting of the economy, the devaluation of the national currency and a stable federal budget deficit are not a mere consequence of the unfavorable global economic situation. The crisis has exposed structural weaknesses of the Russian economy.

INSTITUTIONAL, POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC GROUNDWORK FOR MODERNIZATION

Russia’s ethno-national culture does not include enough modernization values, which can stabilize the reproduction of modern social relations and the demand for technological innovations. The existing cultural specifics seem to have little appeal not only for foreigners, but also for Russian citizens.

Consequently, the task of the modern elite is to focus on this field. It is not about propaganda campaigns, but public efforts towards making the economy one of the most developed and effective. Let them call it a “Eurasian way of development”: it will not change its essence, because by walking along this path, we will achieve what both Europe and Japan have achieved.

Today, Russia has encountered a well-known problem – the necessity to transfer from short-term modernization efforts and reforms to a self-reproducing and self-evolving modern society. This implies a political system with democratic change of government and an economic system with permanent stimuli for innovations in the production of goods and services. Can Russia achieve this, or will its “Eurasian” culture doom it to shuttling between stagnation and mobilization? Broadly speaking, how can one analyze the culture of a society? Is it enough to understand its historical fate?

The crucial question is how today’s modernization differs from the efforts of reformers in the Romanov Empire, starting from the dynasty’s founder in the early 17th century, or from “a breakthrough into the bright future” during the Soviet-era decades of mobilization, or from the change of the social system in the last decade of the 20th century? Offhand, the answer is simple: it was only in February 1917 and in August 1991 that part of the elite that came to power as a result of revolutions really meant to develop a democratic system in Russia. All other modernization projects were apparently aimed at strengthening dictatorship/autocracy and military mobilization. Whether it was done for the sake of a “world revolution” or access to Black Sea straits and Constantinople does not really matter.

All modernization projects carried out by authoritarian leaders were actually mobilizations. In the Soviet Union, Japan, Germany and Italy of the 1930s, mobilization quite openly had the objective to prepare for a large war. One might argue whether the Soviet industrialization could have taken another turn if implemented under Nikolai Bukharin and Alexei Rykov’s plans, but the historical fact is that Joseph Stalin had his own way in carrying it out. As a consequence, the Soviet Union suffered the tragedy of collectivization, brutal reprisals, the retreat of the Soviet Army from the Neman to the Volga in 1941-1942, and the victory in World War II, which was achieved at too high a price.

Even in the “Era of Great Reforms,” the government of Alexander II (1855-1881) modernized Russia largely because of the need to build up its military potential. Elements of democracy – be it independent courts or local self-government – were economic measures in the first place, which ensured stability of private property and eased the burden on the central state budget.

The militarization of the economy usually did not entail expansion of democracy but, rather, its curtailment. The country retreated from what it had achieved in engaging “the lower classes” or “rank-and-file members of the working class and peasantry” in public administration. The Assembly of the Land of the early 17th century did not last long, and absolute autocracy was reinstated. In the early 20th century, there emerged new democratic institutions – provincial assemblies and the State Duma (parliament), but they were abolished after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. The spontaneously-created soviets (local councils) were turned into an appendage of undisguised dictatorship during the Civil War.

Using totalitarian administrative methods, the Soviet authorities carried out a vigorous industrialization, increased quantitative indicators and scaled up production. But the problem of inefficient use of resources was left unresolved. For more than 20 years, from the middle of the 1960s through the early 1990s, the Soviet leadership aimed at raising labor productivity by 2 to 2.5 times but never succeeded. The next two decades, marked by the revolutions of 1991-1993 and economic reforms, brought no solution, either. The efficiency problem is still pressing.

Solving systemic institutional and political problems of Russian society is a pre-requisite and a crucial part of the task to create an effective economic model. Russia has proclaimed a course towards economic modernization, broad introduction of innovative technologies, and the attraction of foreign investments and human capital. Russian companies will have to actively compete with emerging markets in all fields, in the same way as the BRIC countries are actively competing with each other.

All emerging market economies are characterized by high country risks. However, they are outweighed by advantages, such as vast domestic markets, natural resources, and, most importantly, mass cheap and well-trained labor. The Russian economy is obviously losing this competition. Its labor force is expensive and will not become cheaper. At the same time, investments in companies’ fixed assets must increasingly become investments in machinery to replace manual labor.

The demographic situation in Russia does not contribute to a natural inflow of manpower. Russia will inevitably have to import both skilled and unskilled labor. Due to demographic changes in the population mix and the expanding segment of old people who need social security, Russia’s vast market will become increasingly less receptive to advanced high-tech goods. The elderly part of the population will need specialized goods and services.

The economic problems faced by Russia make it a typical Eastern European country. However, unlike most of them, it does not aim at joining the EU’s Eastern Partnership program or the association itself at a later stage. From the author’s point of view, it is a serious mistake of Russia’s foreign policy. Applying the EU’s economic, legal and administrative rules to Russia could have made its economy much more attractive to foreign and domestic investors.

This approach does not rule out successful and mutually advantageous cooperation with neighboring China or other Asian countries. Russia should simply take an untraditional view of seemingly embedded notions. For example, the Nabucco pipeline, traditionally viewed by Moscow as an unfriendly challenge, may well organically supplement Russia’s South Stream project. Iranian gas will inevitably reach the European and Asian markets within a decade or two, and such cooperation will become an attractive business.

In developing the natural resources of Eastern Siberia and creating a potential there for exports to Chinese and Indian markets, Russia will gain not only Asian, but also European and American business partners. In a recent article that addressed cooperation with China, Russian political analyst Sergei Karaganov convincingly proved that the production and supply of food to the Chinese market can become a variant of high-tech export production. It will also contribute to environmental protection and the use of recoverable natural resources. Where else can the Russian economy obtain this money and such technologies if not in the EU and the U.S.?

GLOBALIZATION: FROM THE CHAOS OF THE CRISIS YEARS TO A NEW ORDER

The world economic crisis of 2007-2009 has set many things in their proper place. For many people, the globalization of the economy has turned from an abstract notion into a very tangible economic context, adapting to which is crucial for the survival of countries, companies, people and households. Modernization looks unfeasible without it.

However, neither the Russian business community nor the bodies of state regulation of the economy have learned yet to take advantage of the Russian economy’s participation in globalization.

Russian businesspeople and analysts view globalization as a threat in the first place, or a challenge at best, but hardly ever as a new opportunity. Indeed, the economic crisis has exposed negative consequences of the globalization of the world reproduction process. It has become customary to criticize the expansion of financial markets and the increasing complexity of transactions with derivatives. It was this sphere that was hit by the payment crisis, which collapsed the financial markets in a domino fashion. Yet we should not forget that new derivatives in the financial and commodity markets created the necessary and sufficient conditions for boosting investment in the emerging market economies in the two pre-crisis decades. Innovations in the financial sector helped increase money flows, which are essential for building modern innovative industrial companies and securing the demand for their products.

Thanks to the labor of the population in developing states, financial flows were largely diverted to emerging market economies. The mass export of cheap goods and services from China and India caused structural imbalances in the movement of money flows, such as trade surpluses in these countries and their huge gold and foreign exchange reserves. While giving credit to China’s and India’s obvious achievements, obviously their rapid growth largely rested on the excessive supply of free financial resources, created with new derivatives and bank overleverage.

This set the following pattern for economic relations: on the one hand, the salaries of public-sector employees in the United States directly depend on their administration’s ability to attract dollars accumulated in China’s gold and forex reserves into U.S. government bonds. On the other hand, incomes of a Chinese producer or seller of staple goods depend on the purchasing power of U.S. households. As a result, evaluation of the balance of international monetary flows became the driving force for an overwhelming majority of economic decisions. In turn, the stability of monetary flows depends on a nation’s competitiveness on the world market.

The establishment of the Group of Twenty amidst the crisis and fruitful negotiations within its framework were a major contribution to the stabilization of the economic situation. However, it became clear soon that the main decisions on state regulation of national economies and global ties still have to be made at the national level.

Despite the significant disproportions in the global financial system where the collapse of the derivatives market rocked financial institutions and provoked the bankruptcy of many investment and commercial banks and insurance companies, the U.S., the euro zone countries and the United Kingdom took anti-crisis measures without recourse to international financial institutions. Only the European Central Bank played a major anti-crisis role as the issue center for the common currency, the euro.

The financial disproportions spread to the sphere of state finance. The accrued state liability to the tune of 100 percent of GDP in leading countries predetermined increased inflationary pressure. In this situation, Barack Obama’s administration and the U.S. Federal Reserve System opted for “quantitative easing,” i.e. pumping money into the national and global financial systems. The Bank of England and the European Central Bank followed suit. Although euro zone leaders repeatedly said that an inflationary scenario was unacceptable, it is this scenario that they are actually implementing.

Inflation, economic slowdown or stagnation is the most realistic prospect for the global economy for the next five to seven years. In a sense, this development will be a direct follow-up of the economic disorder in the previous crisis years.

World inflation is not new to international economic relations, as The Economist recently noted. “Between 1945 and 1980 negative real interest rates ate away at government debt. Savers deposited money in banks which lent to governments at interest rates below the level of inflation. The government then repaid savers with money that bought less than the amount originally lent. Savers took a real, inflation-adjusted loss, which corresponded to an improvement in the government’s balance-sheet. The mystery is why savers accepted crummy returns over long periods.” World economy analysts Carmen Reinhart and Belen Sbrancia suggested calling this process “financial repression,” (Liquidation of Government Debt, Peterson Institute for International Economics, April 2011).

The question is whether “financial repression” will be exploited again to resolve the government debt problem. The author of this article gives an affirmative answer to this question. An increase in money supply in dollars, euros and pounds (which in a politically correct language is described as ‘quantitative easing’) has already resulted in higher dollar prices of all commodities in international exchange trade, and a visible increase in domestic prices in the United Kingdom and the euro zone.

The euro zone leadership is openly trying to use this method in resolving the debt problem in countries of Southern Europe. On the one hand, while giving financial aid to Greece, they help it pay debts to private banks in other countries, and on the other, they extend its maturing sovereign debt. Also, such rescheduling will help lower interest rates on national debt. A mounting inflation will make the task of servicing the debt much easier for governments.

In the medium term, inflation will devalue the state debt of not only Greece. The “financial repression” will help repay this debt with inflation-devalued dollars and euros. Banks are also invited to make their own contribution by rescheduling and prolonging debts on their balance. However, the incumbent Greek government is unlikely to benefit from the “financial repression” as it will default on its national debt earlier.

The next stage of world development will not stop globalization; rather, it will give it a new impulse. Banking legislation will become uniform to cover not only accounting principles but also banking supervision, where coordination will give way to joint implementation of budget policy. The EU will set up anti-crisis stabilization funds, like the one now used to provide assistance to Greece. The EU may also introduce taxes common to the budgets of the EU and member countries, like the financial transaction tax, with tax revenue to be shared between the Brussels bureaucracy and national governments.

The Russian government, the business community and society at large will inevitably have to look for a response to this new reality, from which they cannot hide behind state borders. They must ensure Russia’s full-fledged participation in the new stage of economic globalization and, on this basis, find a niche it deserves in the world hierarchy of states. What kind of world we will live in depends on decisions made by the leading powers, even if these powers are presently not doing well. Russia’s strategy may rest on a defense, military-political and economic alliance with the United States and its European and Asian allies and on renouncement of mutual nuclear deterrence, inherited from the Cold War times. The author elaborated on this idea in the article “A New Entente” (Russia in Global Affairs, No. 4 October-December, 2008). The way the situation has been developing since then has only strengthened the author’s confidence that there is no alternative to this scenario.