I. The Eurasian Initiative of the Park Geun-Hye Administration: Assessments and Objectives

In the late 1980s the Roh Tae-woo administration began implementing the Northern Policy, which opened up new vistas for cooperation with countries in the communist camp, specifically China and the USSR. By normalizing diplomatic relations with the USSR and China, the Republic of Korea (RK) could create new space for economic cooperation with the northern states and lay the foundation for quantitative growth. The Sunshine Policy pursued by the Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun administrations, which was focused on encouraging North Korea (DPRK) to take the path of reform and openness, paid special attention to the cooperation with northern Eurasian states. Owing to these efforts, the Republic of Korea’s space for economic cooperation expanded to Central Asia and Mongolia.[1] In 2014, a visa-free agreement came into force between the Republic of Korea and Russia. This created the legal framework for expanding humanitarian exchanges.

However, this quantitative growth failed to promote qualitative improvement, as evidenced by the failure of the trans-Korean gas pipeline project and the Lee Myung-bak administration’s policy of resource diplomacy as a whole. The administration made an attempt to address the North Korean nuclear problem and implement three mega projects – the joining of railways and electric grids and the construction of a gas pipeline – on the basis of a ‘grand bargain’. But the so-called May 24 Measure that followed the sinking of the RKS Cheonan, a South Korean naval ship, banned all forms of South-North cooperation and led to a rupture in inter-Korean relations. Other projects also failed to deliver on account of the North Korean factor. By advancing its Eurasian Initiative, the new Park Geun-hye administration demonstrated firm political will to seek cooperation with the Eurasian countries but, despite initial expectations, the initiative stalled.

Advanced in October 2013, the Eurasian Initiative aimed to open new markets and create growth drivers by using Korea’s development experience and industrial and technological advantages in projects designed to diversify industry, expand transport and logistical infrastructure, and build industrial facilities in Eurasian countries. Yet another aim was to prepare a new environment for encouraging reform and openness in North Korea and promoting stability in inter-Korean relations by involving the DPRK.[2]

Implementing the Eurasian initiative has produced some results. First of all, the Republic of Korea announced its intention to expand cooperation with Eurasian countries in the narrow sense, that is, with Russia and the Central Asian countries, which had been given relatively less attention in the past. Moreover, the formulation of the Eurasian Initiative has put the foreign policy aspirations of a middle-sized Northeast Asian state, which is ready to become a developed nation and a driving force of international cooperation in Eurasia, at the center of international discussions. The initiative also helped to resume talks (in circumvention of the May 24 Measure) on Korean involvement in the Rajin-Khasan project; to sign and put into force a visa-free agreement with Russia for holders of ordinary passports (up to 60 days); to create a Korean-Russian investment and financial platform; to launch a public-private committee for economic cooperation with Central Asian countries; to finalize the Eurasian Initiative roadmap; to hold meetings of the Coordination Committee for Economic Cooperation with Eurasia (under the Korean government); and to pursue joint research into opportunities for establishing a free-trade area with the EEU.

Many former projects, including Northern Cooperation and initiatives to expand interaction with Russia, were integrated and merged as the Eurasian Initiative proceeded. As a result, Eurasia as a strategic space has moved to a prominent position in national policy, which was formerly oriented chie.y towards cooperation with maritime powers. This work has also helped ordinary Korean citizens to realize the importance of cooperation with continental powers.

Nevertheless, the Eurasian Initiative has stalled for the following reasons.

First, the Eurasian Initiative, put forward by President Park Geun-hye at an international conference in October 2013, was not preceded by a thorough elaboration of specific strategies, practical content and implementation methods. This is why the agencies concerned worked on the roadmap after the initiative was announced (until the end of 2014). However, despite their best efforts, the initiative has not been implemented in a systematic way.

Second, the lack of a single center for supervising cooperation with Eurasia is the reason why systemic and consistent programmes have failed to be approved, and those that were adopted have remained unimplemented. Lacking a single system and speci.c strategies, each ministry or agency has created various business units and undertook impromptu measures. For example, the Coordination Committee for Economic Cooperation with Eurasia that includes the International Economic Affairs Bureau under the Ministry of Finance and Strategy and heads of bureaus of relevant ministries, have overseen the exchange of project plans between ministries, summed up their performance, and monitored the proceedings. To implement a presidential project of national importance, a special organizational structure is required, which would have powers to raise a budget, make plans, and administer and coordinate projects of all ministries and agencies. But no such center has been established. Neither has a budget been created.

Third, there is no key channel for communicating with Russia, nor is there a body in charge of consultations. In Russia, decision-making process involves top officials and government agencies, while the most important issues are addressed within the Kremlin inner circle. Therefore, in dealing with Russia it is essential to have close contacts and a relevant channel to communicate with key figures, as well as a specially created body authorized to discuss a broad range of issues.

Fourth, the West’s anti-Russian sanctions and the economic downturn in Russia have played a role. The crisis in Russian-US relations has both restricted South Korean business operations in Russia and affected Seoul’s diplomatic independence. Following the 2008-2009 global economic crisis, Russia, with its limited economic growth model dependent on raw material exports, witnessed an economic slowdown. The United States and its Western allies imposed sanctions on Russia in 2014 and oil prices collapsed in the latter half of the same year. All of these factors led to a dramatic worsening of the economic situation in Russia, the key partner in the context of the Eurasian Initiative.

Fifth, South Korea lacks a specific funding programme, while its project programme is mostly for show, emphasizing ostentatious measures handed down from on-high. Empty declarations and a focus on quick returns are among the reasons why the project has not succeeded. The Eurasian Initiative is a large-scale programme designed for comprehensive economic cooperation with all Eurasian countries and requires a strategic vision.

Sixth, South Korea lacks a flexible approach to North Korea and does not factor in all the risks. Moreover, it does not fully appreciate the fact that Eurasian cooperation should be approached in a wider context without limiting itself to inter-Korean problems alone. Given the absence of shifts in US-North Korean relations, the Republic of Korea would do well to respond to missile and nuclear tests by engaging North Korea in Eurasian cooperation projects that could become a platform for multilateral cooperation. But inter-Korean relations have been blocked instead. Given North Korea’s geographical location, improving inter-Korean relations was seen as both a precondition for implementing the Eurasian Initiative and as its primary aim. This excessively limited approach made sanctions directed at isolating North Korea and bleeding it dry the sole political objective. As a result, all trilateral projects involving the two Koreas and Russia, including the Rajin-Khasan project, the driving force behind the initiative’s implementation, have been suspended and the Eurasian Initiative has proved generally unviable.

There was also a number of constraining factors, such as insufficiently developed local communications channels, inefficient management of the intergovernmental cooperation development policy, underestimation of the Russian market’s potential, an inadequate information support system that hamstrung Korean businesses on their way to the Russian market, weak financial incentives for Korean businesses to boost exports to Russia and vie for Russian orders, and the focus on short-term economic gains at the expense of a long-term strategic approach.

As a result, the Eurasian Initiative has assumed a rather abstract form: ‘united continent’, ‘creative continent’,‘peaceful continent’. There were great hopes for Korean-Russian cooperation. The lack of results has led to disappointment and distrust.

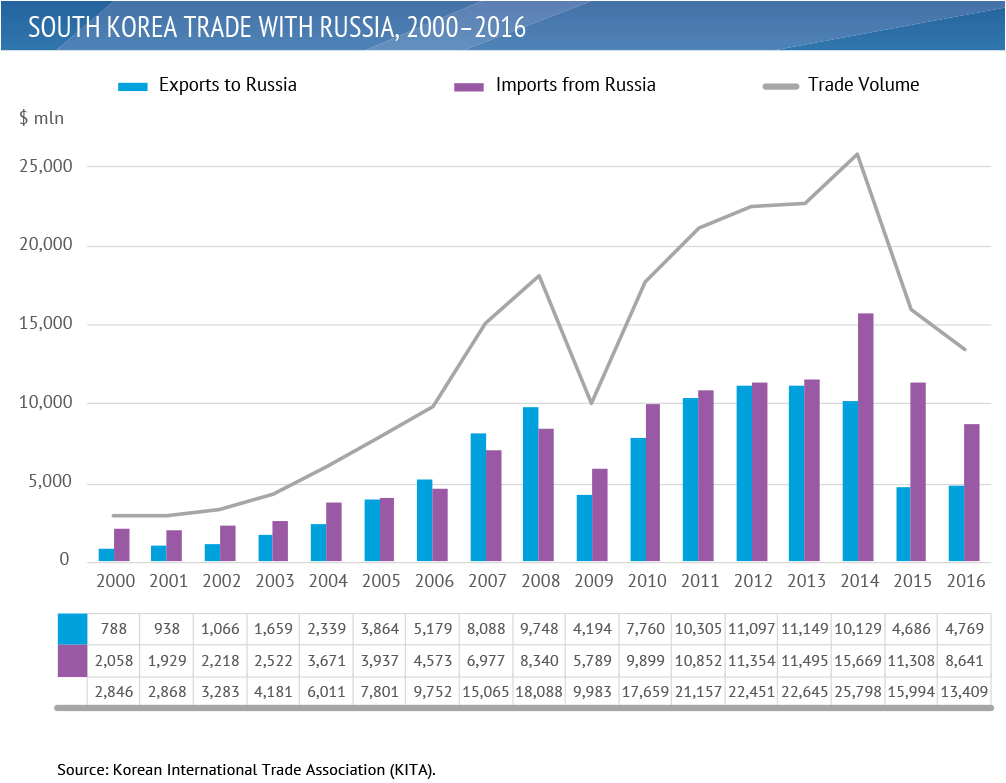

Economic cooperation between the Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation has declined dramatically in the process. In 2016, Russia fell to the 19th place on the list of South Korea’s trade partners (1.5%). Fortunately, Korean-Russian trade grew by 58.9% to $5.8 billion during the first four months of 2017 as compared to the same period in 2016.

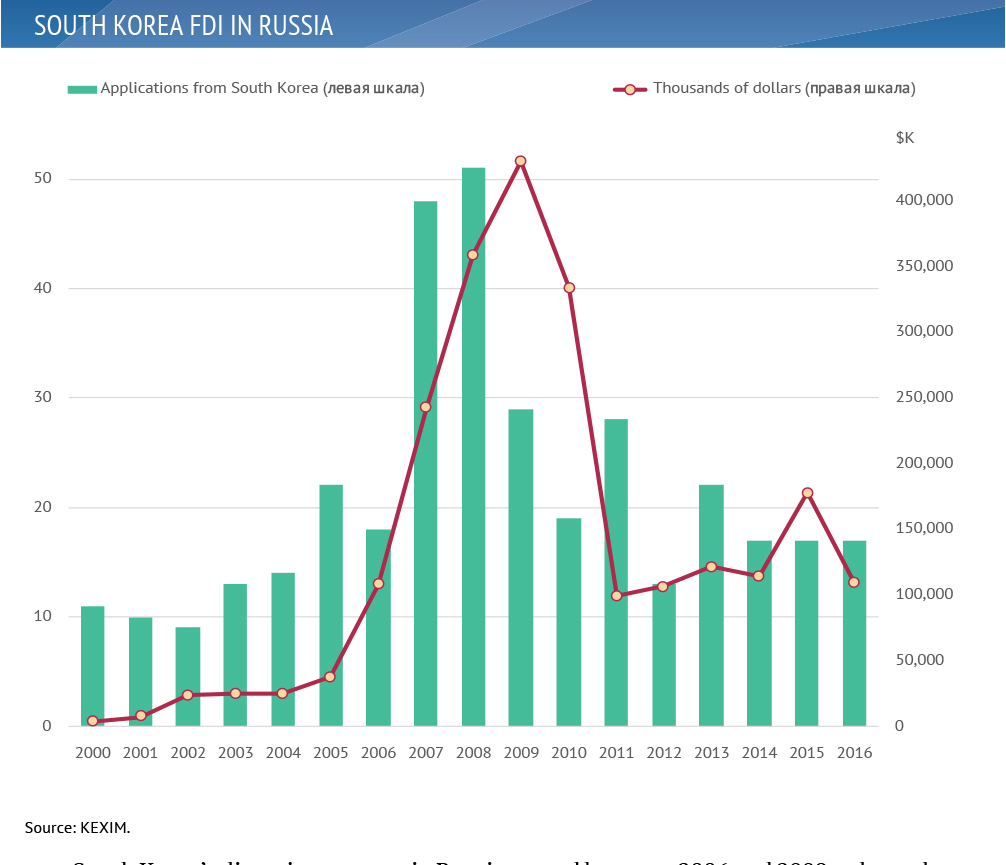

South Korea’s direct investment in Russia surged between 2006 and 2009 only to plummet thereafter as a consequence of the global financial crisis.[3] As of the end of 2016, Korean accumulated direct investments in Russia amounted to $2.5 billion. The Russian share of foreign direct investment in the Republic of Korea shrunk from 1.38% ($334 million) in 2010 to 0.32% ($110.4 million) in 2016.[4] Korean investment in Russia goes mostly to the electronics, auto and food industries, as well as the services sector. As a consequence of the economic stagnation in Russia in recent years, the number of new legal entities from the Republic of Korea seeking access to the Russian market has dwindled: from 52 in 2007 and 62 in 2008, to 21 in 2014, 18 in 2015, and 17 in 2016.

There is no doubt that the scale of Korean-Russian economic cooperation has grown over the past years, as has the spectrum of cooperation. But the level of cooperation itself is far below both the potential of South Korea that ranks among economically advanced countries, and the huge Russian potential. Evidence of this is the low Russian share of South Korea’s foreign trade (1.2%), the insignificant amount of Russian direct investment in South Korea (less than 1% of all foreign direct investments), and the low level of Korean business involvement in resource development and infrastructure projects in Russia.

The Russian economy has faced temporary problems in recent years induced by Western sanctions and low oil prices. However, gradual economic recovery is expected in 2017, and therefore we can assume that the demand for Korean-Russian cooperation will grow significantly in the future.

II. The Rise of Eurasia and Russia’s Accelerated Turn to the East

The Northern Policy initiated by the Roh Tae-woo administration has been further advanced, regardless of which government was in power, and has remained a nonpartisan issue. Although the previous government’s Eurasian Initiative has not yielded results, with the current global trends it can be assumed that northern Eurasian states will play an important role in the new government’s foreign policy.

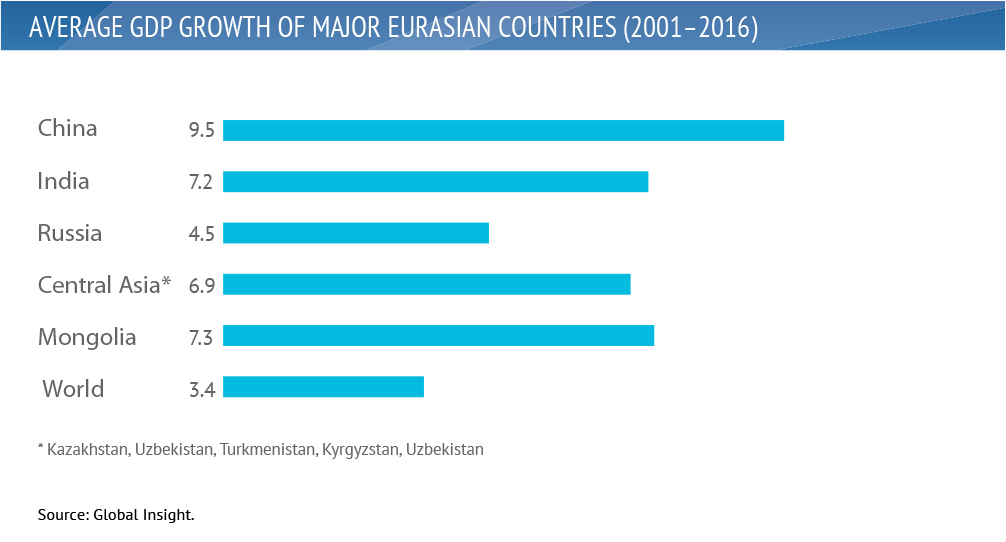

The architecture of international relations is going through a rapid transformation in the modern world. While the European project is in crisis (Brexit) and the North Atlantic paradigm (American trade protectionism) is weakening, Eurasian integration processes are accelerating: China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the Russia-centric Eurasian Economic Union, India and Pakistan’s accession to the SCO and its expansion. In a broader sense, there is an economic upsurge in Eurasia.[5] With the rapid growth of major Eurasian countries’ macroeconomic indicators in 2016 – including Russia, China, India, the Central Asian states, and Mongolia – the strategic value and significance of the continent have grown substantially.

These are the circumstances in which Russia is making its turn to the East, which accelerated after Vladimir Putin’s reelection in 2012. In fact, Russia began showing interest in Northeast Asia (NEA) and the Asia-Paci.c region (APR) in general back in the early 2000s, but the turn to the East intensified only in recent years. In 2012, a specialized Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East – the .rst of its kind – was established, an Asia-Paci.c Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit was held in Vladivostok, and the federal targeted programme Socioeconomic Development of the Russian Far East and the Baikal Region to 2013 was adopted. The Eastern Economic Forum (WEF) has been held on a regular basis since 2016, and new development institutions have been established, including the Advanced special economic zones (ASEZs) and Vladivostok Free Port.

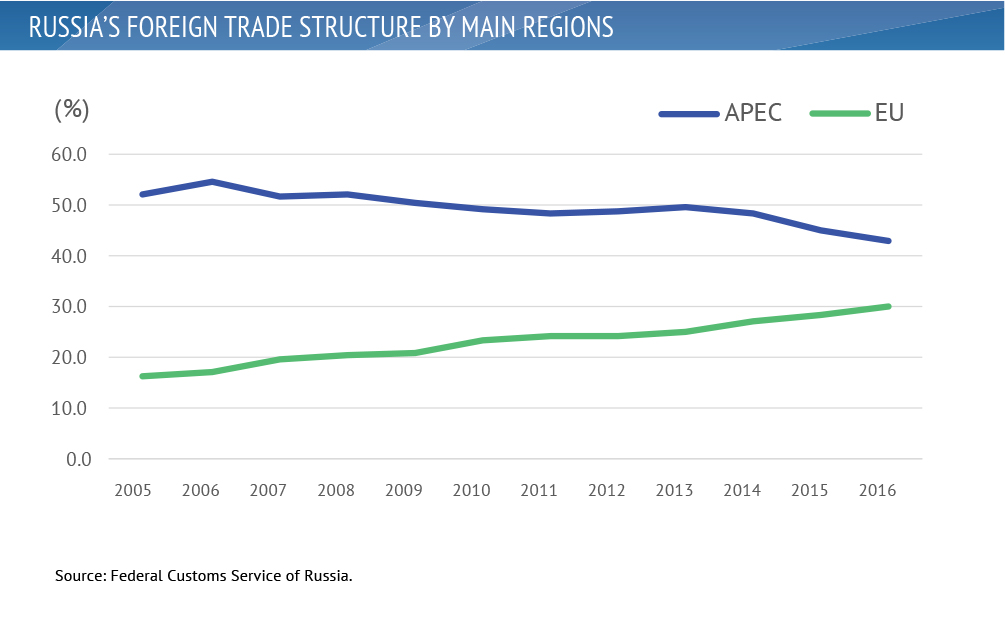

It is too early to weigh the results of Russia’s turn to the East, but it is obvious that its economic ties with APR countries have significantly expanded over the past decade. Until the mid-2000s, Russia’s foreign trade was highly dependent on the European market. With the accelerated implementation of the Far East and Siberia development programme and the turn to the East, the share of Asia-Paci.c countries in Russia’s foreign trade structure has grown considerably. In 2005.2016, the EU’s share in Russia’s trade shrank from 52% to 42.5%, while that of APEC countries surged from 16.2% to 29.8%, and this trend seems likely to continue in the future.

On December 3, 2015, the Russian president delivered his annual address to the Federal Assembly in which he proposed creating an economic partnership between the countries of the Eurasian Economic Union, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Later, in June 2016, speaking at the opening of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF 2016), Vladimir Putin introduced the idea of a Greater Eurasia or a Greater Eurasian partnership including Russia, the EEU countries, the CIS, China, India, Pakistan and other states. This aspiration was reaffirmed by the country’s leadership at the 2016 WEF.[6]

This kind of Eastern policy should be considered in the context of the EU’s and NATO’s eastward expansion. Having secured strategic cooperation with China, Russia is responding by taking steps to expand the SCO, which already includes India and Pakistan, and supporting the expansion and development of the EEU. This should help Russia consistently gain a stronger foothold in the APR, including Northeast Asia. For the Republic of Korea, the expansion of Moscow’s presence in the APR, including NEA, is a good opportunity to strengthen cooperation with its northern neighbors.

Guided by the idea of a ‘Euro-Pacific power’, Russia is striving to expand the horizons of cooperation throughout the continent. The Republic of Korea, in turn, can expand cooperation with Eurasian states in energy, transport and logistics, aligning its Eurasian initiatives with the Greater Eurasia project. In other words, the Republic of Korea, which links Eurasia with the Asia-Paci. c region, should strive to intensify cooperation with Russia and other Eurasian countries, playing to its geopolitical and geo-economic advantages.

III. Cooperation between the Republic of Korea and Russia: Areas and Goals

Following the establishment of diplomatic relations, bilateral cooperation between the Republic of Korea and Russia went through a stage of development and quantitative growth. However, today, despite the proposed Eurasian Initiative, bilateral interaction has come to a standstill. Now, more than ever, breakthrough solutions are required.

The Russian economy is expected to start its gradual recovery in 2017, and presumably demand for Korean-Russian cooperation will increase substantially as a result. In 1998, after Russia declared a moratorium on debt payments, unlike their Western counterparts, Korean companies did not leave the Russian market. Instead, they continued to work to expand their ties, con.dent of the Russian market’s promise. That is why Korean businesses rank .rst on the market of household appliances, and Korean brands have become the people’s choice in Russia.

Korean-Russian cooperation has not yet entered a new era or reached a qualitatively new level. Nor has the practical content of bilateral cooperation changed to reflect Russia’s focus on the eastern vector in its policies. To achieve this, it is imperative to develop new approaches. Now is the time for the parties to take steps in order to embark on a path of cooperation while expanding interaction in the sphere of energy and services, abandoning the earlier model of exporting finished products. Also, Russia and Korea should strengthen joint investment activities and strive to promote industrial cooperation.

It’s time to abandon the old policy of ‘patching up’ current issues of the bilateral agenda and undertake thorough efforts in order to put together systematic and consistent medium.term and long-term plans for cooperation with Russia and Eurasia, as well as to promptly form a regulatory framework underlying its implementation. In its cooperation with Russia, the Republic of Korea pursues the following main goals.

Goal One. Creating a system of Korean-Russian interaction aimed at establishing peace on the Korean Peninsula and uni.cation. Without close cooperation with Russia, instability on the Korean Peninsula will only increase. Tensions caused by the North Korean nuclear threat and the deployment of the US missile defense system (THAAD) persist. Building its relations with Russia, the Republic of Korea seeks to ensure peace and stability, while creating opportunities for common prosperity on the Korean Peninsula and in Northeast Asia.

Goal Two. Searching for sources of economic growth and creating a third component of northern economic cooperation. Economic cooperation between the Republic of Korea and Russia is complementary, so there is every reason to believe that bilateral cooperation will ensure sustainable coexistence and mutually beneficial economic development of the countries. The Republic of Korea faces the task of creating the third route for northern economic cooperation, following the route of maritime cooperation with the United States and Japan, and a route of interaction with China. To this end, the Republic of Korea needs to strengthen its economic cooperation with Russia strategically, and be the first to develop the ‘space of northern economic growth’.

Goal Three. Expanding international cooperation in Eurasia and forming the corresponding institutional framework. Strong integration processes are underway in Eurasia. Russia initiated the creation of the EEU, while China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ and New Silk Road initiatives are underway. The SCO borders are expanding, with Russia and China playing the central role. Given these circumstances, the Republic of Korea should begin actively searching for ways to participate in the international cooperation developing in Eurasia. Such steps will not only help to lay the foundations for institutionalizing international cooperation in Eurasia, but will also boost economic growth in the Republic of Korea.

The main areas of cooperation between the Republic of Korea and Russia can be articulated as follows.

Area One. Establishing a basis for cooperation aimed at restoring mutual trust between the parties and creating drivers to advance interaction. It is also desirable to expand industrial cooperation, which should be the focus of such efforts. It is important to start with practical projects in sectors such as tourism, agriculture and livestock production, fisheries, logistics, medicine, and healthcare. In tandem, phased-in investments are needed in key infrastructure projects, such as energy, port infrastructure, roads, warehouses, and maritime transport. This approach will create a track record of success. In addition, to re-invigorate the investment activity of the Korean private sector, the government needs to think about the sources of financing, starting with state investments as an example.

Area Two. Detailed study of ways to cooperate based on changes in the behavior of North Korea (through engagement in these efforts or, conversely, risk minimization). On this basis, it is necessary to prepare a scenario for developing cooperation. In the effort to restore inter-Korean relations, it is imperative to create infrastructure for inter-Korean uni. cation and to strengthen trilateral cooperation with the participation of the two Koreas and Russia in order to develop transport-logistics connectivity.

Today, North Korea is an isolated state that seeks economic cooperation with a limited number of countries led by China. Trilateral projects involving the two Koreas and Russia, which are linked to international projects in Eurasia, remain the only practical tool for involving North Korea in regional economic cooperation. By participating in the construction and use of infrastructure, Economic benefits that North Korea will get from participating in infrastructure projects will make it realize the need to use its geopolitical location and become a partner in regional economic interaction. In other words, Pyongyang will come to realize that it is necessary to change its existing pattern of foreign economic activity characterized by strong dependence on China.

Alternative measures should also be considered. If no settlement is possible in inter-Korean relations, the format of trilateral cooperation between the two Koreas and Russia should be transformed into a format for cooperation between the Republic of Korea, China and Russia. While forming a new format of cooperation, it is imperative to envisage measures to involve North Korea in the future.

Area Three. Phased-in solutions to tasks aimed at sustainable development of relations. In the short term (one to two years), efforts should be directed towards creating the basis for cooperation and expanding industrial cooperation. In other words, it is necessary to abandon the old practice of discussions, formulating strategies and programmes for the sake of abstract and unattainable goals. The efforts have to be directed at developing bilateral industrial interaction, beginning with setting clear and readily attainable goals. In the medium term (three to five years), all efforts should be directed towards full implementation of priority tasks and achieving results. On the basis of bilateral industrial cooperation, it is necessary to fulfill all priority tasks, and then move on to implement trilateral projects involving North Korea. In the long term (six to 10 years), the focus should be on ensuring that cooperation is sustainable. Expanding the horizons of cooperation to the borders of Eurasia, it is important to actively participate in bilateral and multilateral cooperation projects, including regional mega-projects.

Along with such efforts, the system for practical implementation of the outlined plans to strengthen cooperation with Russia and the Eurasian states needs to be revised.

First of all, a special unit for cooperation with Eurasia should be created in the government. The Republic of Korea did not do enough to ensure regular bilateral summits. Also, the absence in the government of a unit responsible for working with Russia and the Eurasian states, and the overall lack of a systematic approach to cooperation with this region, led to a situation where the implementation of corresponding programmes and strategies was not always consistent and responsible. So, professional, sustainable and responsible work to develop cooperation with northern states, including Russia, calls for creating a special independent division within the government. For example, it could be a special committee for cooperation with Eurasia, which will answer directly to the president. Due to the lack of such a government task force, medium-term and long-term strategies and tasks have not been properly executed, which, in turn, hampered cooperation with Russia and the Eurasian states.

Along with the creation of a dedicated committee, it is advisable to transform the department for Eurasia into a separate directorate of the Republic of Korea’s Foreign Ministry, and take it out from the directorate for European affairs. In addition, a Foundation for Cooperation with Northern States should be formed within the Ministry of Strategy and Finance to support the investment activity of small and medium-sized businesses on the Russian and Eurasian markets. Cooperation with Eurasia for the Republic of Korea is a new driver of future economic growth. This is precisely why the government must adopt an active position and take decisive action. It would also be advisable to hold regular high-level meetings and meetings in the 2+2 format (foreign and economic ministers). The Eastern Economic Forum, which enjoys special attention of the Russian leadership, could be the best platform for holding regular meetings at the top level.

In the medium and long term, it will be possible to consider using this venue as an advisory body for the north and the south of the Korean Peninsula, Russia, China, Japan and Mongolia. With regard to the 2+2 meetings, the current Korean-Russian committee on economic, scientific and technological cooperation could be expanded and taken to a new level. Activities to transform the intergovernmental committee will ensure the regularity and sustainability of the 2+2 meetings, which could prove instrumental in promoting economic and diplomatic cooperation.

IV. The Future of Russian-South Korean Relations: Expanding Bilateral Cooperation

In order for Russia and the Republic of Korea to expand economic cooperation, the two countries should start by creating a foundation by stepping up industrial, as well as trade and investment cooperation. At least three key issues have to be taken into account.

First, the establishment of a free-trade area between the Republic of Korea and the EEU is essential. In the Asia-Paci.c Region, the EEU has already entered into an agreement to this effect with Vietnam, and is currently exploring opportunities for signing free-trade agreements with India, Mongolia, Singapore and the Republic of Korea.[7] Given Russia’s central role within the EEU, an FTA would pave the way for new cooperation concepts and strategies, entailing the emergence of shared Eurasian values. In addition, this step would create growth opportunities for a new Eurasia.

In other words, this agreement would be a ‘window to the APR’ for Russia, and a ‘window to Eurasia’ for South Korea. In 2016, the two countries completed the preparatory work in the drafting of a FTA-like Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement, and are expected to launch talks on signing it. Russia and South Korea could add momentum to this process and step up cooperation by forming a bilateral investment facilitation committee.

Second, expanding the Russian-Korean investment and financial platform and actively using it is very important. On November 13, 2013, the Export-Import Bank of Korea (KEXIM) signed a three-year Memorandum of Cooperation with Russia’s VEB to set up a $1 billion financial platform to support projects in Russia, including in Russia’s Far East and Siberia. However, the Russian-Korean platform has yet to be launched. This is attributable to a number of key factors, including the sanctions imposed against Russia by the West, the fact that suitable projects are hard to find in a stagnating Russian economy and the hypersensitivity of Korean businesses to country-related risks, especially in dealing with Russia’s Far East and Siberia. The agreement to ensure parity in financial investment is another factor. The memorandum was renewed in late 2016, which means that there is a need for more substance to this document moving forward. It should be viewed as one of the key elements on the bilateral economic agenda, emphasizing the need for further review of the cooperation framework and methods. These matters should be discussed at the working level in order to specify the geography in which the platform will operate, the cooperation framework, identify industries that will benefit from support, as well as work out the modalities and methods for providing this kind of support. These discussions should provide a foundation for developing cooperation mechanisms that will be more flexible.

Third, a package of measures should be devised with the view to supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are ready to become involved in investment projects. Facilitating investment by SMEs is one of the key objectives in terms of bilateral cooperation and a way to promote hands-on cooperation. Business-to-business ties among SMEs are directly related to programmes to modernize Russia’s value-added industries. This kind of cooperation could also create new jobs which would help Korean SMEs further improve their manufacturing quality and promote their practices on the global market, as well as make them more competitive. Consequently, projects to support SMEs and stimulate investment provide an opportunity for promoting joint strategic projects with the leading Russian manufacturers (investment and technology cooperation, development of projects to tap the markets of third countries).

In addition, strategic industrial cooperation could help overcome low growth, high unemployment and other challenges both countries are facing, helping ensure sustainable growth. In order to expand industrial cooperation, efforts to promote cooperation should focus on the following areas:

- Creating a partnership network based on the ASEZs of Russia’s Far East and Russia’s special economic zones (SEZs). Russia’s industrial modernization policy is aimed at consolidating and upgrading its manufacturing base. By creating new development institutions, including SEZs, ASEZs and the Free Port of Vladivostok, the Russian Government is seeking to attract investment and facilitate exports. Consequently, there is a need to clearly articulate cooperation opportunities for Korean SMEs willing to work with Russian producers in SEZs and ASEZs. This could help create strategic cooperation models. Building on these achievements, the two countries should move on to create a framework for medium-term industrial cooperation.

- Cold chains (food transportation infrastructure) should be created in Russia’s Far East. Even though this region is rich in sea bio-resources, Russia still exports them without any processing. It is for this reason that the Russian Government has taken a number of measures to develop bio-resource processing. In order to deliver on this objective, the cold chain should include a processing center in the Free Port of Vladivostok. This would help increase exports of processed . sh and .sh products with high added value. Specifically, this chain could include the following stages: a .sh processing plant in Russia’s Far East – refrigerated storage – fish meal plant, etc.

- Expanding the Republic of Korea’s involvement in agriculture in Russia’s Far East. A mutually beneficial cooperation system should be devised in order for Russia to deliver on its objectives to increase grain exports, and for creating a Korean food base abroad. In addition, new agricultural projects should be launched in Russia’s Far East. In the future, these could be trilateral projects, bringing together the two Koreas and Russia. Efforts are now underway in Russia to improve its agricultural infrastructure, including the construction of a grain terminal, while Korean farmers are interested in taking part in these projects. There is every reason to believe that in the medium-term, North Korean workers could contribute to the creation of an agricultural complex in Russia’s Far East (a project to create glass greenhouses, using pasture for dairy production, creating a pork and poultry processing plant). Considering the appeal of enterprises of this kind, the parties must combine efforts in exploring ways to engage in agricultural projects, and use the results of the study to decide on the investment by Korean farms and the size of government support.[8]

- There is a need to expand transport and logistics cooperation, primarily by upgrading and resuming the Khasan–Rajin railway project. The Khasan–Rajin railway is a pilot project of trilateral cooperation between the two Koreas and Russia. However, South Korean companies are unable to take part in it due to the worsening of relations between the two Koreas and the sanctions against North Korea. Just as before, Russia is interested in resuming this project as a matter of priority. However, any talk of restoring direct relations between the two Koreas, including resuming the Kaesong Industrial Zone or the ‘Golden Mountains’ projects, seems premature. For this reason, initiatives to open up North Korea and promote reform should start with trilateral cooperation projects with Russian or Chinese participation, and in compliance with UN sanctions. Projects of this kind could become the key tools for promoting ‘Northern cooperation’, setting North Korea on the path of change. Three successful cargo deliveries have already been accomplished within The Khasan–Rajin project. Containers made up the third shipment. The successful delivery proved that this route could become part of a logistics project offering high added value and returns.

- A port and logistics system should be created in Russia’s Far East in order to promote the Northern Sea Route for commercial cargo shipments. The development of this trade route should be part of a stage-by-stage process to develop an intermodal transportation system linking the key ports to continental logistics centers and supply routes throughout Eurasia. In the short-term, the project to create a specialized Korean terminal and link it to other port infrastructure facilities and surrounding territory should undergo a feasibility study by Northeast Asian countries: Japan, Russia and China as they strengthen their partnership network. In the medium-term, these projects should be expanded, including by linking ports along the Arctic coast with the main continental shipment terminals and logistics centers and developing and managing international intermodal transportation.

- An ongoing effort is needed to create a Korean-Russian energy system. Even though the trilateral project to build a gas pipeline was suspended due to instability in intra-Korean relations and lack of economic efficiency, KOGAS and Gazprom could continue talks on natural gas imports by entering into a new bilateral gas deal. Pipeline gas imports should be viewed as an objective for the medium-term, while focusing on stepping up LNG shipment from Sakhalin-2 in order to guarantee stable distribution and the best prices. At the same time, the project to link energy grids also has long-term implications, taking into account the results of the joint feasibility study since there is no way this project can bypass North Korea.

- Russia should account for a larger share of foreign direct investment in South Korea. In fact, Russia has been increasing its FDI since the mid-2000s, and has become a global investor. Russia’s FDI was equal to $28.4 billion in 2012, $70.7 billion in 2013, $64.2 billion in 2014 and $26.5 billion in 2015. At the same time, the share of Russia’s overall foreign direct investment in the Republic of Korea remained quite modest: $19 million in 2012, $8 million in 2013, $22 million in 2014 or 0.067%, 0.011% and 0.034%.[9]

In order to attract foreign direct investment from Russia, the Republic of Korea should hold various conferences to show off its appeal for investors, as well as launch an awareness campaign. This could provide the foundation to further expand mutually beneficial economic cooperation, while also producing the desired foreign policy and defense effect to ensure stability on the Korean Peninsula. Until the mid-2000s Russia was highly dependent on Europe in its foreign trade. Russia’s turn to the east and focus on developing its Far East and Siberia led to more trade with the APR countries.

It was against this backdrop that the EEU signed a free-trade agreement with Vietnam. The deal entered into force in October 2016. Today, efforts are underway to enter into a similar deal with the other ASEAN countries. The investment and business climate in Russia have been improving lately. In fact, between 2010 and 2015 Russia moved from 120th to 62nd in the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking and was ranked 40th in 2016.[10]

Consequently, we have every reason to believe that the New Northern Policy and Russian proactive efforts in the APR, as well as the improved investment climate create favorable conditions and good opportunities for taking economic cooperation to a new level. In other words, all the conditions are now in place for expanding cooperation in Russia’s Far East and Siberia, as well as across Russia, and developing the Arctic territories and the Northern Sea Route. All in all, the time has come to expand and strengthen strategic cooperation with Russia.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai International Discussion Club

[1] For example, the RK’s comprehensive state strategy for reaching Central Asia was approved in 2007 during the Roh Moo-hyun presidency.

[2] For more detail on the RK Eurasian Initiative, see: Jae-Young Lee, 2017, ‘Korea’s Eurasia Initiative and the Development of Russia’s Far East and Siberia’, in ‘The Political Economy of Pacific Russia’, eds. Huang, J & Korlev, A, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 103–125.

[3] Between 2008 and 2010, investment grew by over $300 million per year, but it dropped to $110 million in 2016, according to KOEXIM data, Foreign Investment Statistics, access date: 23.03.2017.

[4] Russia accounts for 2.51% (2.9% in 2014) of Korean foreign direct investment in BRICS, which is much less than the share of China (75%), Brazil (15.5%), and even India (6.92%), according to KOEXIM data, Foreign Investment Statistics, access date: 23.03.2017.

[5] Lee Jae-young, 2017, ‘To solve North Korea issue, Moon administration should pursue northern cooperation’, The Hankyoreh, June 1, p. 21.

[6] Flegontova, T, 2017, ‘Russia’s Approach and Interests’, Valdai Discussion Club Report, March, p.12.

[7] Vinokurov, E, 2017, ‘Eurasian Economic Union: Current state and preliminary results’, Russian Journal of Economics. no. 3, p. 66.

[8] Lee Dae Seob, 2017, ‘Koreiskoie selskokhozyaistvennoe proizodstvo na rossiiskom Dalnem Vostoke’ [Korean agricultural production in Russia’s Far East], EKO, no. 5, p. 43-60.

[9] According to the Central Bank of the Russian Federation. Available from: http:/www.cbr.ru (access date: 23.03.2017)

[10] According to the World Bank, Doing Business Data. Available from: http://www.doingbusiness.org/data (access date: 28.03.2017)