The world economy enters a new phase of prolonged recession and uncertainty. Over the past half-century, globalization and underpinning international governance such as the WTO have led global economic growth. Since the global ?nancial crisis of 2007-2008, however, the world economy has failed to create new growth engines. There seems no breakthrough in sight. Nevertheless, international community is no longer capable of creating new global initiatives as major nations are struggling to tackle a variety of socio-economic problems. The recession and the absence of global cooperation almost automatically add instability and fear of protectionism to the global economy. The bleak landscape of the global economy is paradoxically the product of globalization that hauled the previous decades of economic growth. So the immediate challenge is how the international economic community manage the new landscape of the world economy in the face of increased uncertainties and lost growth momentum of globalization.

Prolonged Recession; It’s Structural Rather than Cyclical

Worldwide recession is here to stay longer than we want. The world economy is failing to recover from the almost a decade long recession except for a short period of V-type come back from the 2007–2008 global ?nancial crisis. The current situation seems to betray the hope that the recession is only a cyclical one rather than a structural one. The world economy witnessed euro zone crisis, slowing of the Chinese economy and weak demands form newly developing markets in recent years. We tend to believe that the current recession can be explained by these relatively shorter term events. However, we should remind ourselves that these events originate again from the possibly fundamental changes in the world economic structure.

First of all, the rapid ‘financialization’ of the economy must have increased the overall volatility in the global economic system. Major economic regions have experienced, one by one, continual financial crisis over the last few decades. The fragility of the financial markets is not only detrimental to efficient resource allocation but also fast contagious across regions adding uncertainty to international economic activities of trade and investment. We have observed that a financial crisis of a particular country had seriously negative impacts on periphery countries as international investors in center countries quickly adjust international portfolios. The so-called ‘Wake-up Call Hypothesis’ is quite plausible considering highly integrated international capital market. Developing countries particularly in Asian regions have to accumulate their hard-earned foreign currency through active export. They have to keep sufficient level of foreign reserves as an insurance policy against the fear of potential financial crisis. Obviously, the insurance policy, otherwise being potentially productive capital, weakens effective demands in the developing world. The overall sluggish demand also comes from more structural changes such as global and domestic income inequality and fast aging of major societies. While these changes seem to be almost perpetual, policy spaces of governments are limited mainly due to the high level of public debt, record low level of interest rates and distorted balance of powers between market and public sector.

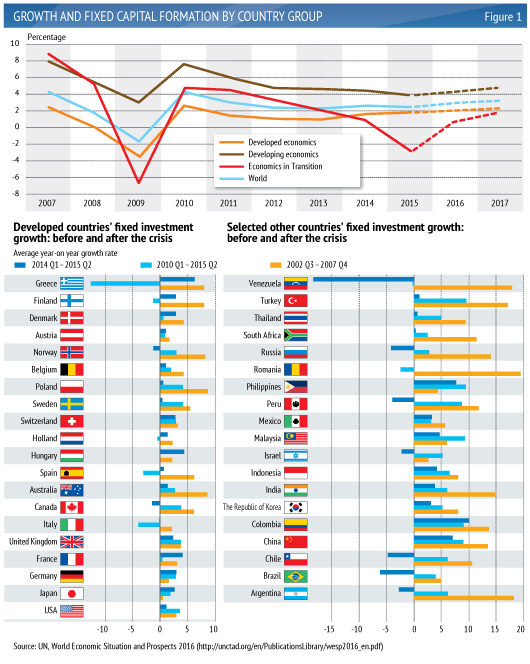

Figure 1 supports the pessimistic expectation presented above. It shows that every country group of different economic development stages has experienced lower economic growth for a decade than before the global financial crisis. While the growth prospects are positive for the year 2016 and beyond, most institutions are downgrading their forecasts recently. Even the positive prospects are greatly hinges on uncertain assumptions of rebounding of effective demand in the near future particularly in the major emerging markets.[1] The bottom panels of Figure 1 shows that the gross fixed capital formation in most countries dropped signi?cantly since after the global financial crisis except in the few numbers of countries like the U.S, Japan, Germany and France. While the economic rebound is most conspicuous in the U.S, it has not proven to be suf?cient enough to boost overall world economic conditions. It seems quite appropriate to put the popular new tag of ‘New Normal’ to the current situation of the world economy.

Is Globalization Hitting the Wall?

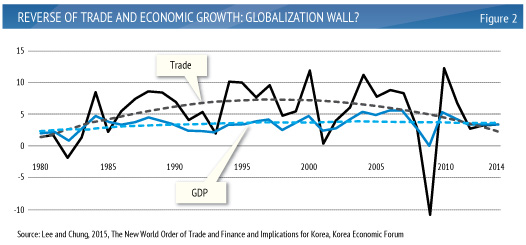

The prolonged slowdown of the world economy may be signaling the end of export-led growth in the age of globalization since 1980s. Globalization may have reached to a limit in many respects after it has played as growth locomotion of the world economy. Since 1980s, the growth rates of world trade has hauled overall economic growth. Recently, the trend seems to have overturned; growth of trade is slower than the economic growth. Figure 2 clearly shows that the fitted lines of trade and GDP growth crossed around 2013 and 2014.[2] It is afraid that world trade is settling down in the lower growth trend around 3% while it had maintained growth rates above 5% for the most years of recent decades. The world economy has not experienced such reversal of trends before. Particularly, the share of capital goods in total imports gradually dropped from 35.0 per cent in 2000 to 30.1 per cent in 2014, whereas consumer goods maintained their share of about 30 per cent throughout the same period.[3] The trend exactly is consistent with the stagnant fixed investment described in the Figure 1. If this trend continues, it would impose a serious challenge to the developing world, particularly the East Asian countries. In the absence of sufficient expansion of world demand, increased economic sizes of export-oriented emerging markets can create a zero-sum game situation among countries adopting export-led growth strategy. The situation may call for a new growth policy space for many countries, and it is highly likely that protectionism would be included in short lists of policy options.

The potentially new trend of trade and economic growth may reflect an intrinsic limit against furthering of globalization. That is, the world economy may be facing at the ‘Globalization Trilemma’, which says it is just impossible that the world integrates national economies in full scale allowing certain level of sovereignty and democratic relationship at the same time.[4] Globalization initiatives, popular for a long time, are becoming too a costly option for politicians and policy makers as we have witnessed in the US presidential election process. Therefore, the world economy may have reached the stage at which not only globalization can lead the world economic growth, but also globalization itself can no longer expand its fronts any further. Major countries do not have sufficient political capitals to create a system of international economic cooperation. It is almost impossible for international community to agree upon any resolution to call for further sacrifice of sovereignty, which is necessary for strengthening international economic governance in order to push forward further globalization.[5] Recent development of the U.S domestic politics indicates that no country has big enough political capital to take the leadership of creating a mechanism for new global economic governance. Countries seem busy looking inside rather than outside their borders.At this point, the right question must be how the world economic system could effectively manage the hard-earned current platform of economic cooperation including the WTO.

Widening Global and Domestic Income Inequality

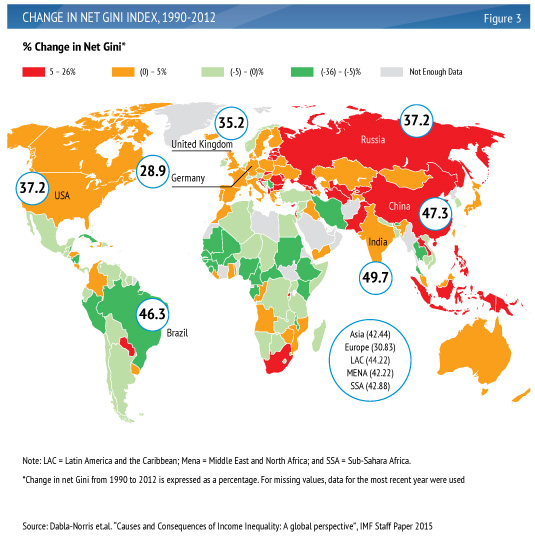

In 2015, the IMF reported that the income inequality continued globally. It was quite a news that the same observation was released by the IMF itself because it has been the leading organization of the globalization wave for longer than a half century. Now it is natural to receive such reports warning aggravated income inequality and blaming globalization at least partially. Figure 3 from an IMF report (Dabla-Norris, et.al, 2015) summarizes the global trend of income inequality. Evidently, the situation has aggravated in most major economic regions. For instance, we can find huge increases of GINI indices in China and Russia in which the indices show not only fast increases but also high absolute levels. Major advanced economies in the North America and Europe also showed significant growth of inequalities while Europe is still of relatively equal situation of income distribution. We can find some improvement in less developed regions of Africa and Latin America. However, their absolute levels of GINI are still too high and they are the regions still struggling for the basic socio-economic problems of very limited access to education, health and financial services.

While reducing income inequality itself is an important policy objective today, there are growing numbers of evidence that it is also an effective way to promote economic growth. A trading partner country with high income inequality yields less bilateral trade flows through lower import demands.[6] More balanced income distribution provides stronger effective demand necessary for stable economic growth considering the disparate marginal propensities to consume of the rich and poor income groups. Also, if a society fails to improve the income distribution, it could face a risk of falling into a vicious cycle of low growth and aggravated income inequality. Following the logic of IMF, it is true that both the technological gap and globalization may be responsible for today’s income inequality. However, high income inequality again can widen the technology gap between countries and between social groups within a society with accelerated globalization. It is highly likely that the potential benefits of globalization tend to be limited in a relatively smaller group of high income. Globally widening income inequality is an important background for a pessimistic prospect on the future of the world economy.

Understanding the Real Value of the WTO

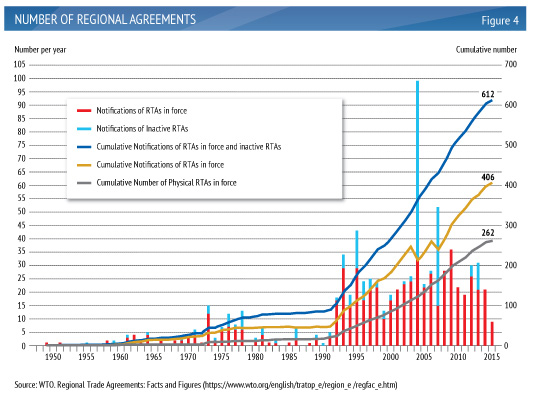

It is no doubt that the launch of WTO in 1995 was one of the most important achievements of the international community. It has the most comprehensive governance over commercial policies and trading activities with binding mechanism for dispute settlement. Ironically, however, the birth of WTO ignited explosive expansion of regional economic agreements, mostly in the form of FTA [7]. Principally, regional economic agreements pursue trade and investment liberalization among a few numbers of contracting parties. They are in line with the objectives of the world trading system under the WTO. However, as the basic mechanism of regional economic agreement is to provide preferences to members in the block, they create discriminatory impacts on world trade flows, hence potentially resulting in distortions in resource allocation globally.

Proliferation of regional economic agreements is almost an inevitable result of the development of global economic governance. The highly liberalized world market under the WTO provided a favorable environment for increased international production sharing by not only multinational enterprises but also medium and small sized ?rms. It is natural that production sharing activities resulted in creating agglomeration of industrial activities leading to a new regional economic geography. Once the WTO was established, private sectors seemed to find it too costly to pursue UR-type multinational trade negotiation from the cost and bene?c perspectives. The WTO is a platform for ‘markets (exports and imports) for markets’ as well as code of conducts with respect to trade policy measures. The practically failed DDA[8] is the proof that the multilateral trading system has reached to the point where the marginal bene?t of negotiation efforts is far less than the expected marginal bene?t of further liberalization of world market. This argument is well supported if we compare the scopes of the DDA and the UR. The latter ?rst time in the history, introduced service markets and trade related IPRs into the realm of the multilateral trading system. The DDA is, at most, a mere attempt to improve market access achieved during the UR. The private sectors simply do not ?nd any appetite to push for another round of multilateral trade negotiations. It was natural to pursue regional economic agreement as an alternative as it provides more direct and immediate market access for contacting parties.

Of course, in spite of this argument, the failure of DDA does not deny the value of the WTO. It is now working as more of the manager of the world trade activities and the supervisor of code of conduct for trade policy than as a marketplace of international trade. The current multilateral trading system is successful enough to manage trade practices against returning to protectionism.

The Diminishing Marginal Bene?t of Regional Trading Blocs

The theory of the New Economic Geography (NEG) explains that the improved market access through globalization (by both multilateral and regional initiatives) prompts agglomeration of industrial activities in major economic regions or regional central economies. The increasing return to scale is the very ?rst factor behind the asymmetric space distribution of industrial activities. It is advantageous for manufacturing industries in particular to be concentrated rather than dispersed geographically with respect to the bene?ts of the economies of scale. Secondly, NEG explains with monopolistically competitive behavior of businesses when gathered around limited geographical area; businesses tend to rationalize the size of production activities to take advantage of the economies of scale. Also, the formation of an industrial cluster creates a variety of external effects such as supply of skilled labor, procurement of intermediate goods and technology spillover. Therefore, regional economic clusters generate gravity to invoke further concentration of industrial activities. Regional economic agreements reinforce agglomeration of industrial activities. NAFTA created a new industrial zone along the US-Mexico border as businesses took advantage of the improved market access to both markets by actively engaging in international production sharing targeting both markets. Distribution of major industrial regions and existing trade agreements clearly overlaps. That is, regional economic agreements are distributed around regions of most active industrial activities in north America (West Сoast regions of the U.S, US-Mexico Border), European region (EU members and Сentral European countries) and East Asia (China, Korea, Japan and China-South East Asia border region).

The expansion of regional economic agreements is a natural response of policy makers to pressures from markets; there has been growing demand for regional economic agreement from both regional economic leader and followers to support for international production sharing activities. However, the wave of regional trade blocs after the WTO seems to have reached to the final stage. Most of the major trading countries already joined multiple numbers of regional trade agreements. More than two hundred regional trading agreements are in force and more agreements were notified to the WTO (See Figure 4). The widespread of regional trade agreements brought about much broader and deeper integration in addition to the improved market access provided by the multilateral system.

Obviously, it would decrease again the marginal bene?ts from further efforts for establishing additional trading blocs. Regional trade agreements reduced trade barriers signi?cantly while they are adding economic and political costs domestically. The recently stumbling TPP [9] best supports this argument. TPP is a unique attempt by the USA to pursue improving market access at semi-multilateral platform. On the one hand, the initiative is the plan B of multilateral approach of global integration. The active involvement of the USA in TPP in recent years signals its pessimistic view on the future role of multilateral trading system in furthering market access globally as witnessed by the failure of DDA. On the other hand, the TPP is a grand experiment of whether a semi-multilateral version of regional trade agreement is achievable. It is formally an FTA of a grand scale. The doomed destiny of TPP is not because of the large scale itself but of the intrinsic political risks from furthering globalization. As we have discussed earlier, it is an interesting observation that recognition of the social costs of further globalization sees widespread among the public of the USA. Considering its political verdict in the process of the US presidential election, it is hardly likely that the US politics would seriously consider TPP at least during the early years of the new administration. In the European front, euro zone crisis and the recent BREXIT referendum can be interpreted in a similar way, raising the question of whether EU can go on further integration. The initiative of RCEP by China has not entered into a meaningful negotiation process.

Transition to Nationalistic Approach and the Fear of Protectionism

Of course, there is every reason to worry about protectionism in the face of the structural changes of world economy and appearance of nationalistic politics in both the USA and Europe. The recent increasing fear of protectionism is understandable because the new president of the U.S. is vividly painted as advocating protectionism seeking national interests over international cooperation. In the European front, Brexit is a ground for protectionism concern because it makes policy makers to believe populations are against further integration of world markets.

However, from economic point of view, the nationalistic approach is a plausible option to avoid economic and political costs associated with the internationally cooperative approach. Trump’s pressure on China and members of NAFTA and revoking TPP are signs of policy transition from a cooperative approach to nationalistic approach. In efforts to appease his constituents, Trump may bring trade cases against China, both under U.S. trade remedy laws and before the WTO. The transition is exactly consistent with the economic logic of proliferation of regional trading block after the WTO as we discussed earlier. The nationalistic approach is just an attempt to gain national interests with lower economic and political costs. Precisely speaking, the nationalistic approach is to improve market access to targeted countries. At the same time, threats to impose high tariffs are hardly realistic considering closely integrated production network between the U.S. and targeted countries. The previous attempts in 1990s to revoke the MFN treatment to China were never realized just because they would harm the interests of huge number of the US investors in China. Also, it is difficult to relate Brexit directly with protectionism, per se. After the referendum, the U.K. made it clear that it would engage into trade negotiations with major trading partners. It is hardly conceivable that the U.K. would want to raise trade barriers against negotiating partners than before. On the contrary, Brexit may be a liberal option to avoid costs of regulatory system imposed by the EU. Remember that the EU is not just a regional economic integration but is a political process to realize the ‘European Federalism’. Brexit is another case of nationalistic approach by conservative politics seeking smaller government, rather than a manifestation of protectionism.

So, the fear of protectionism may be somewhat exaggerated. Threats of protectionism are hardly realistic whereas nationalistic approach could end up with mixed results, sometimes with more liberalized markets. The real worry is that the nationalistic approach would increase trade disputes among trading partners. It would accelerate the recent increasing trend of discriminatory measures by major trading countries under the prolonged recession of the world economy. It’s time to recognize what the international community has achieved in this regard, the WTO. As mentioned earlier, the WTO is more competent as the supervisor of code of conduct for trade policy than as a marketplace of international trade. The current multilateral trading system is successful enough to manage trade practices against returning to protectionism. We have witnessed the value of the WTO as a stabilizer of international trade during the global financial crisis in 2007-2008 when pundits cried out for possible return of the pre-World War II type of protectionism. Protectionism never been a serious concern after the crisis thanks largely to the operational capacity of the WTO to bring trade disputes between member economies in the dispute settlement mechanism. Therefore, it is time that the international community has to be content with the current role of the WTO in defending the world economy from protectionism, instead of blaming it for not being competent enough to materialize more ambitious market liberalization.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai International Discussion Club

[1] For instance, IMF’s world economic outlook update of July 2016, after the Brexit Referendum, downgraded 0.1% point for the world economic growth in 2017.

[2] Lee and Chung, 2015, The New World Order of Trade and Finance and Implications for Korea, Korea Economic Forum.

[3] For more details, see UN World Economic Situation and Prospects, 2016.

[4] Rodrik, Dani, 2007,‘How to Save Globalization From its Cherleaders’, The Journal of International Trade and Diplomacy 1 (2), Fall 2007: 1-33.

[5] As it will be discussed below, the almost dead ‘Doha Development Agenda’ reflects the limit of WTO’s competence.

[6] Arjona, Ladaique, and Pearson, 2002, Social Protection and Growth, OECD Economic Studies No.35.

[7] Free trade agreement, FTA. – Ed. note.

[8] Doha Development Agenda, DDA. – Ed. note.

[9] Trans-Pacific Partnership, TPP. – Ed. note.