As a result of the present worldwide economic crisis, and the twin challenges of climate change and global energy security due the huge energy demand of Asia, and China and India in particular, the world is confronted with “unprecedented uncertainty” for maintaining global energy security, as the International Energy Agency (IEA) warned in November 2010. According to the IEA’s central scenario, the so-called “New Policies Scenario,” the world’s primary energy demand will increase by 40% between 2009 and 2035, with the non-OECD-countries accounting for 90% of the projected increase.

The recent revolutions in North Africa, the unrest in Bahrain and the following military intervention of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as well as the civil wars in Yemen and Libya have caught the entire international world by surprise and led to disruptions of supply of oil and gas to Europe and other parts of the world. In the EU, and particularly in Italy and Spain, the widespread domestic instabilities in the Arab world have highlighted the challenge of energy supply security, its dependence on the political stability of oil and gas producers in the Middle East, and the geo-economic and geopolitical importance of the “Strategic Ellipse” (Persian Gulf and the Caspian region), where over 70% of the world’s remaining conventional oil and more than 40% of the world’s remaining conventional gas resources are concentrated.

Alongside of the growing LNG markets, which further pushed globalization, one national development had been missed out by most of the major international and national oil and gas companies (including Gazprom) until around 2006–2007: The development of unconventional gas in the U.S., in particular shale gas. The release of unconventional gas resources triggered a revolution in the global gas market. Unconventional gas not only transformed the U.S. energy market, and in particular the natural gas market, but it also became the tipping point of a fundamental change in global gas markets. An increase in the U.S. incremental non-conventional shale gas production coincided with other critical economic, political, and technological factors – the drop of demand linked to the global recession and the arrival of new LNG delivery capacity – which together created a sudden global “gas glut.” It laid the groundwork for an expanded role of natural gas in the world economy, which prompted the IEA to envisage a “Golden Age of Gas.”

THE EU-RUSSIAN ENERGY PARTNERSHIP AT A CROSSROADS

Together with the nuclear reactor catastrophe in Fukushima (Japan) in March 2011, Russia was hoping to benefit from the aforementioned geopolitical developments by declaring itself an island of stability, willing and able to expand its oil and gas deliveries to the EU-27. It could re-define the EU-Russian Energy Partnership after years of rising mutual mistrust and continuing crisis as a result of the Russian-Ukrainian gas price conflicts and other controversial foreign policy issues (Estonia 2007, Georgia 2008, etc.).

When Germany revised its energy policies last summer with its decision of phasing out nuclear power by 2022 and eight nuclear reactors already since April 2011, Russia offered immediately another 20 bcm of natural gas per year to compensate for the loss of nuclear power. At first glance, Russia’s position appears stronger than ever. In 2010, 13 European countries still relied on Russia for more than 80% of their total gas consumption; and a total of 17 countries were dependent for more than 80% of their gas imports on Russia. Moreover, the IEA has forecasted that Russia’s projected increase of its gas production will be greater than in any other gas producing country between 2009 and 2035, accounting for no less than 17% of the worldwide gas supply increase.

While Russia will remain the EU-27’s largest source of energy imports, the EU will remain Russia’s largest trade and modernization partner. However, confronted with the rising global competition for energy resources and raw materials, and re-nationalization of the world’s energy sectors, the EU’s energy policies have pushed a liberalization policy for its internal market and fastened common energy policies and political solidarity between its member-states in order to maintain its overall economic competitiveness in the future.

In the EU, the expanded use of natural gas by acquiring a larger share of the EU’s overall energy mix and the increased diversification of gas imports can translate the EU’s energy security from being an “Achilles’ heel” to a future energy “stabilizer.” But the global developments have created major challenges for the future EU-Russian energy partnership. The “Third Energy Package” to create unified and liberalized energy and gas markets by establishing rules has forced energy companies to “unbundle” their transport (pipelines and storage) activities from their production and sales, which has already caused frictions and a conflict of diverging interests in the bilateral relationship.

While the EU’s diversification strategy for its gas imports has clearly been recognized as another major challenge for Russia’s and Gazprom’s traditional gas strategy, in the EU view, the changes of the global gas markets appear to have either been overlooked, dismissed or at least marginalized by Russia. The Kremlin and Gazprom seem more interested in maintaining highest possible gas prices linked to the oil prices, rather than defending its share in the European gas market. Thus its share of EU gas imports has fallen from almost 50% in 2000 to 34% in 2010. Equally, the share of the EU in Russia’ total gas sales revenue has dropped from 60% to 40% within the last decade.

Therewith the EU-Russian energy partnership and its Energy Dialogue, launched in 2000, are in the midst of fundamental change. It is not so much the result of EU-Russian relations in general but much more of fundamental changes of the EU energy policies and global energy developments, particularly in the world gas markets. It has created new uncertainties on all sides. While EU member-states already struggle to cope with the rapidly changing energy environment on a global level, in the view of the EU, the Kremlin and Gazprom appear rather to stick to their traditional energy strategies and positions, overlooking or being unwilling to recognize its fundamental changes and geo-economic implications.

Since 2000 the EU has made significant progress in liberalizing its gas sector and formulating common energy and gas policies. In October 2010, a Council Directive has adopted a legal framework “to safeguard security of gas supply and to contribute to the proper functioning of the internal gas market in the case of supply disruptions,” including with new effective mechanisms and instruments to guarantee political solidarity and coordination. It has emphasized the need for priority infrastructure programs such as the “Southern Gas Corridor” and diversified an adequate LNG supply for Europe. The cross-border nature of the new infrastructure investments of new gas and electricity interconnectors and harmonized security of supply standards are overviewed and coordinated by the Agency for Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER; established in 2009), the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSO for Gas; established in 2009) and the Gas Coordination Group as an Advisory Body of the European Commission.

In February 2011, the first ever European Council meeting dedicated to energy decided that the internal gas and electricity market should be completed by 2014 and declared the objective: “No EU member-state should remain isolated from the European gas and electricity networks after 2015 or see its energy security jeopardized by lack of the appropriate connections.”

Criticizing the Third Energy Package of the EU’s internal market rules and the Commission’s anti-trust prosecution of energy companies (ownership unbundling: separating gas supply business from gas transportation), Russia insisted that EU jurisdiction should not extend to pipelines and other critical energy infrastructures. The Kremlin has demanded exemptions or sought derogations from the Third Energy Package (i.e. for the South Stream gas pipeline). In the European Commission’s view, Russia may retain control of critical energy infrastructure assets (such as pipelines) in EU countries (blocking access to competing suppliers) without offering the EU the same opportunities for its own pipeline network in Russia. Hence the lack of reciprocity and the asymmetric nature of the “interdependent” EU-Russian energy relations would be deepened, giving Russia a lasting upper hand over the EU.

While Russia interpreted the EU “unbundling” policies as a “confiscation of property” (as Prime Minister Vladimir Putin put it in February 2011), the EU views these rules as a pre-condition not just for enhancing the competitiveness of its energy sector but of its entire economy with other countries and regions. In this regard, the “unbundling” issue and the conflict between the EU and Russia result from the existence of different economic-political orders in an era of new powers rising outside of the Transatlantic region and a tectonic shift in the global power balance to the Asia-Pacific region.

THE CHANGING EU ENERGY MIX AND THE DIVERSIFICATION OF EU GAS IMPORTS

The growing concern about the EU’s gas supply security is the result of a combination of worrying trends such as its increasing reliance on the more environmentally friendly natural gas resource in its energy mix, its depleting own gas resources in the North Sea, an increasing dependency on Russia and its only gas export company (Gazprom), as well as its heavy dependency on an inflexible pipeline system in a major crisis in contrast to oil and LNG ships which can be sent to other gas fields and countries when a technical or political supply cut-off is taking place. Those concerns are increasing in the light of the global demand for natural gas. According to the IEA’s optimistic “Golden Age of Gas”-scenario, the IEA expects an annual growth of 1.4% of natural gas consumption (altogether 44%) between 2008 and 2035 – making it the only and the cleanest fossil fuel for which demand will be higher in 2035 than in 2008.

To strengthen its future energy security, the European Commission’s energy demand management strategy has emphasized the broadest possible energy mix, diversification of energy supply and imports, promotion of renewable energies, and a neutral policy towards the nuclear option. The 20-20-20 percent formula of its “Energy Action Plan” (EAP) of March 2007 aims to reduce Green House Gas Emissions (GHGE), raise the share of renewables, and improve energy efficiency and conservation. While the 20% objective for enhancing energy efficiency is presently doubtful, the other 20% for expanding renewables will probably be surpassed and may even reach 30%, according to the newest forecasts. As a result, the future EU energy mix will look very different by 2020, and significantly impact the future EU energy demand in general and gas consumption and imports in particular (see below).

In the coming years, the EU will not only increase its gas imports via new gas pipelines from North Africa, but also from Norway and various other countries as part of its diversification strategy. While the North Sea gas fields are depleting, new large oil and gas discoveries in Norway, record high capital investment, new field allowances and decommissioning cost tax relief for investors in the United Kingdom indicate that the North Sea gas supplies will play a longer and more important role as a source of supply for EU gas imports than it was forecast just two years ago.

The development of the Southern Corridor in Southeast Europe with gas imports from Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and northern Iraq has been defined as a strategic project. Gas production in Central Asia and the Caspian Region (CACR) is expected to rise from 159 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2009 to around 260 bcm by 2020 and more than 310 bcm by 2035. Gas exports are forecast to grow rapidly from 63 bcm in 2008 to 100 bcm in 2020 and more than 130 bcm by 2035. But recent discoveries of new gas fields in Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan suggest that the future regional production and export levels might even rise much higher than previously forecast. Turkmenistan’s government, for instance, expects total gas production to reach 230 bcm annually by 2030, which now appears more realistic than two years ago.

Although CACR cannot and won’t replace Russia as Europe’s most important energy partner, it is viewed as an important supplementary supplier and an alternative diversification source for oil and, especially, gas supplies to the EU. Thanks to the EU’s combined diversification efforts concerning the future rise of its gas imports, by 2020 it will have a capacity of more than 300 bcm of non-Russian gas supplies (doubling the present capacity in addition to Russia’s current 150 bcm exports to the EU-27).

With the newly agreed TANAP gas pipeline between Azerbaijan and Turkey, reducing the length and costs of the Nabucco pipeline (“Nabucco West”), the Southern Corridor project has become much more realistic. In addition, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, both rejecting Russia’s objections to building a 300-km long underwater Trans-Caspian gas pipeline, have made considerable progress in their negotiations with the EU and, reportedly, will sign some kind of agreement until the end of this year. Hence, it is not surprising that the IEA expects a stagnation of Russia’s share in the EU’s total gas imports by 2020 and a further gradual decline from 34% to 32% by 2035. But its share of the EU’s total gas consumption may slightly recover from 23% in 2009 to 27% by 2035. Nonetheless, the share of the EU in Russia’s total gas sales revenue might further fall from 40% in 2010 to less than 30% by 2035 as a result of Russia’s forced diversification of its gas exports and the rising value of its domestic sales.

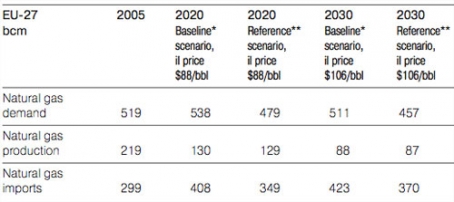

As the world’s largest energy producer and exporter, Russia understandably seeks “security of demand” as it had previously planned for up to 200-220 bcm of natural gas exports annually by 2030 in comparison with around 150 bcm at present. While the IEA still maintains its forecast of a rising EU import demand from the present 300 bcm to more than 500 bcm by 2035, the EU itself and many independent experts are rather skeptical about it and forecast a much lower rise of its imports as a result of its changing energy mix and policies to enhance its energy efficiency (even then when the EU will not fully achieve its 20% target). Indeed, according to the newest gas forecast, the EU-27’s gas import demand by 2030 could be even lower than 400 bcm or at least not significantly higher (see above). This is also explained by the fact that no EU member-states have followed Germany’s decision to phase out nuclear power in the mid-term perspective. Switzerland, Italy and Bulgaria have given up plans for building a nuclear power station, but not phased out reactors presently in operation.

While best-case EU forecasts might be seen as too optimistic in decreasing the gas demand, the IEA’s and the European gas industry’s forecasts might be too optimistic for the European gas industry alike. Eurogas, for instance, has already decreased its own gas demand forecasts for the EU, albeit it appears still too high. At least, there is a consensus among European experts that there is no certainty about the EU gas demand in the next decades.

Table 1. EU-Gas Forecast of 2010