As Russian political experts and the media analyzed the outcome of the political events of 2012, they came to a conclusion that it would be best to forget that strange and controversial year as quickly as possible and hope that 2013 will bring something completely new.

However, there is no general consensus regarding forecasts for 2013. Three possible scenarios are frequently mentioned: (1) the government will keep on applying pressure to the protest movement; (2) the incumbent political regime will continue to deteriorate, the conflict will intensify between Russian citizens and the government, and the present political system will weaken; (3) 2013 will be another uneventful year for Russia, as weak action on the part of both the authorities and the opposition will accomplish nothing. Amid the struggle between various interest groups for financial and property resources, politics will still be conducted behind the scenes.

Even though many people would rather forget about 2012, the year’s events will not likely fade into oblivion anytime soon. The widespread protests were actually the first serious “stress test” for the political system built in the 2000s. The outcome remains to be analyzed and evaluated.

PARALLELS WITH THE 1980S

Russians habitually look to the past to make sense of the present. The country’s elites are not inclined to draw parallels with what is happening abroad and are not well informed about similar developments in other countries (Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Romania, Venezuela, Pakistan, Myanmar).

In 2012, both supporters and opponents of the Putin regime frequently drew parallels with events of the late 1980s-early 1990s – if not in connection with the policy of reforms (although similarities between the failed “Medvedev thaw” and Mikhail Gorbachev’s successful perestroika policy easily come to mind), then in connection with a growth in public action. Without a national consensus on certain events in Russian history, drawing parallels with the same event may lead to the opposite conclusion. The approaches common among the elites (listed below) require an explanation: those methodologies (except for the first one) rarely were a guide to action, and their proponents were not disposed to publicize their vision of the future.

The “August 1991 putsch-style” approach. The government’s biggest mistake in the 1980s was that it was weak, yielded to internal and external “enemies,” and, as a result, lost power. The incumbent authorities should learn from the past, remain tough, and not try to please their Western partners – then everything will be fine.

The “1980s” approach (which is more characteristic of those who lived in Moscow and, to a lesser degree, Leningrad during the perestroika years). Public activity is an indicator of trouble and everything could be lost if it is ignored. Importantly, the line between the “putschist” and “1980s” approaches is not between “reactionaries” and “reformers.” Each of these (largely virtual) groups has their own “eighties’ devotees” and “putschists” – today they exist among siloviki, in the government, in the United Russia party, and in parliament. It is difficult to determine which of the groups is larger and stronger – members of the elites often had to struggle for their careers and respond to challenges created by the authorities.

The sacral approach. The state is all-powerful and President Vladimir Putin has not lost his political initiative, therefore he will have his own way. One needs to adapt to reality and try to translate personal ideas of the beautiful into life. People who hold this view most often rationalize it by believing that the alternative is even worse or by an exaggerated belief that a global cabal is interested in destabilizing Russia’s political regime.

The system-centric approach. The main risk in this approach is the destruction of the “system” as such – not so much existing political institutions, but the real system of administration and financial decision-making. A weaker system will result in a catastrophic disruption of existing balances: a “war where everyone is fighting each other,” a repartition of spheres of influence and property, the criminalization of society, and widespread chaos. Many proponents of this approach speaking off the record expressed concern that Putin is losing his awareness that the existing system should be preserved at all costs, and that he is even shaking it loose for tactical reasons.

The fatalistic approach. The proponents of this approach readily accept the possibility of dismantling the political system – “at first, Alexei Navalny will come to power through a revolution; then several generals or nationalists will win; after which the weakened power will pass from hand to hand.” At the same time, while the current political regime is strong and relatively efficient, there is no sense in dismantling it; instead, one simply needs to adapt to new realities.

A personal approach to history frequently serves as a watershed among individual opposition groups. For some, the 1980s are a guide to action and an indication that success is possible. For others, the decade is a mere abstraction – either those people had not been born yet, or they did not feel the era deeply enough because of what they were doing, or they failed to make use of those times because of their lack of initiative. Therefore, the former intuitively believe in the growing strength of the protests. They compare 2012 with 1990 (when, despite the formal strengthening of “democratic’” positions, there was a sense that the demonstrators were gradually losing the initiative), since events similar to 1991 will inevitably follow. Soviet-era poet and writer Daniil Kharms (1905-42) said: “Life defeated death by a method unknown to me;” a phrase that is more in tune with those who believe success is possible. They are not ready to think about ways to achieve victory; rather they are thinking about how not to waste its rewards. By contrast, skeptics are not inclined to draw historical parallels or they recognize the vulnerability of doing so. This group is prone to hesitation, depression, and, like the Kremlin’s supporters, talks about differences within the opposition, a decline in protests, and their own impotence in the sense that “sooner or later everything will be more or less bad.” In the second half of 2012, these sentiments dominated among the opposition.

These factors shaped a paradoxical situation. One way or another, most of the political players viewed the relationship between the government and protesters in Moscow as the key intriguing development. However, since the collapse of the Soviet Union had caused a psychological (in some cases, phantom) trauma for a large section of the ruling class, the elites tended to overestimate the potential and prospects of the protests. In turn, the opposition movement’s leaders and members underestimated the possible effects of their actions.

This was the background against which political developments unfolded in 2012. And there is no reason to expect that anything will change fundamentally in the upcoming months.

THE ENIGMA OF THE PUTIN PROJECT

During the 2012 presidential election, Putin’s campaign team posed him as “Putin 2.0” – that is, a more modern president who can meet the expectations and requirements of “advanced” users. Experts found this term lacking. Many critics still regard Putin as a twentieth-century man with peculiar ideas about modern methods of competition and permissible boundaries of dispute with his opponents. Serving his country means for him serving the state. However, even though Putin has not “rebranded” his image, he has returned to the presidency as a markedly different man. It is still hard to determine to what extent the reactionary trend in 2012 was a manifestation of Putin’s readiness to take revenge for perceived humiliations he received from the opposition and for Dmitry Medvedev’s four-year presidency, and to what extent it was a purely technological tactic. Like Gorbachev, who in the late 1980s avoided giving clear signals about which side he was on, Putin is not rushing to make any unequivocal statements. He does not oppose the “August 1991 putsch-style” approach and, although he was the instigator behind many of the more moot ideas, at the same time he maintains a relatively balanced rhetoric. This aspect was manifested, for example, in his 2012 address to the Federal Assembly.

Another interesting phenomenon is Putin’s new tactics towards the protest movement. Whereas the government as a whole expects a decline in the protests, provocative high-profile moves by the security agencies tend to incite large-scale protests. A few examples include: verbal assaults against the protesters whom Putin described as “Bandar-log” (monkeys from Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book (1894)) in a December 2011 televised question and answer session; apartment searches of activists Alexei Navalny and Ksenia Sobchak on the eve of a June 12, 2012 opposition protest; and pushing a controversial adoption bill through parliament. Quite possibly, stirring up large protests in this way is a technological tactic intended to show that, even at the height of its activity, the opposition is unable to build an effective strategy and become a full-fledged participant in the political process.

The main question about Putin is: Does he have a new ambitious and coherent project that he intends to consistently implement? Factors that support the existence of such a project include: attempts to tighten administrative control over the elites; growing fears on the part of the president over the worsening situation on international markets for Russia; and more active efforts to build ideological constructs to ensure the loyalty of Russian citizens (“fear of change,” then “Orthodoxy,” and finally “patriotism”). If such a project does exist, then the actions of the authorities may become more targeted and consistent. Work on individual elements of the “project” may continue, but Putin, for now, has the initiative, which will help keep the system from becoming obsolete.

Moreover, the style of exacerbating things, time-tested in domestic politics and which provides for the artificial creation of problems in order to benefit from the solution, may be used more actively in foreign policy. Exerting more pressure on post-Soviet countries could compensate for a lack of diplomatic leverage with G8 countries. However, these efforts could incite opposition even from countries other than Ukraine, Belarus, and Turkmenistan. Recent harsh criticism by Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev about plans to restore the Soviet Union has shown that there is a limit to Kazakhstan’s loyalty too.

However, even if there is a “Big Idea,” there are still several questions to answer:

- The overall viability of Putin’s new project and how adequate it is for existing economic and political challenges against the background of the controversial foreign experience of “self-reliance” in the context of globalization.

- How does the project relate to the expectations of Russians who are experiencing another round of social pessimism? There are a growing number of people who do not want change, but who cannot live in this way any longer.

- How to deal with overwhelming pessimism among the elites, who lack not only the tools to become more competitive, but even an ounce of faith that positive change is possible in at least some areas (investing in science, overhauling the healthcare system, fighting corruption, etc.). Without change, there will always be the risk that the elites will view Putin’s return to power not as evidence of the system’s consolidation, but as his biggest mistake.

- Doubts about changing the existing system. Economic reforms are not being implemented because of government paralysis and a social demand for paternalism. Serious anti-corruption efforts may lead to destabilization among the elites. Conservative ideas or efforts to involve the Russian Orthodox Church to help deal with corruption have not proved effective and actually have turned into a joke.

- There is not any protection against self-destructive initiatives that could diminish the loyalty of politically indifferent citizens. The state’s attempts to position itself as a warrior against social vices by slapping restrictions on the consumption of tobacco and alcohol, imposing a ban on gambling, and censoring the Internet affect broad sections of the public who did not expect such moves on the part of the federal government.

- There is no obvious consensus on the viability of the proposed project.

Yet the main risk for the project is its vulnerability to random factors. The Russian economy is still largely dependent on global markets, which is important considering the (possibly irreversible) decline in revenue from gas exports. The return to “manual control” over Russian politics in 2012 has gradually reduced the number of those who are ready to go all the way to uphold the inviolability of the incumbent regime. Active involvement on the part of law enforcement agencies in politics weakens the role of legislation as a method of social self-regulation and hurts the reputation of previously authoritative institutions, such as the courts or the Church. Additionally, there is no guarantee that repressive orders will be carried out at the grassroots level because of declining administrative discipline and possible issues of loyalty among those who execute those orders.

ONSET AND DECLINE OF POLITICAL REFORM

When the protests began the Russian government hesitated between the “August 1991 putsch-style” and “1980s” scenarios. In December 2011, the government came out with a political reform plan. The plan was not intended to meet the protesters’ demands (actually, it did not have much in common with them at all), rather it was meant to solve several problems: reduce the degree of pressure on the authorities by reviving expectations of possible liberal measures, preventing splits in the ruling class, and, possibly, causing division among the protesters.

The first two problems were resolved.

The government ignored protestors’ demands calling for the overturn of the election results and the resignation of Central Election Commission chairman Vladimir Churov, yet there was a sense that the Kremlin was ready to consider the possibility of early elections to the State Duma, at least as a backup option. It was not accidental that two of the three key elements of political reform concerned the lower house of parliament – the registration of smaller political parties and changes to parliamentary election rules. Another move, the quick reanimation of the Mikhail Prokhorov project, gave rise to timid expectations about an alternative. However, actual changes were merely cosmetic and reflected the conventional wisdom that the authorities were ready to discuss any issue with the opposition, except for the issue of power.

As regards division among the elites, the authorities unexpectedly drew lessons from previous crises (including the “parade of sovereignties” in the late 1980s). The idea of returning to direct gubernatorial elections made it possible to prevent protest sentiment in the regions and the local authorities from coming together. The latter were offered a carrot in the form of federal support for the popular idea of elections. Incumbent governors (at least the strongest of them) were given the opportunity to consolidate their status. At the same time, their opponents hoped that they could now rise to power through elections under the current political regime, rather than through support from the opposition and a regime change at the federal level.

As a result, the protest movement, which in December 2011 swept Russia’s 50 largest cities (including in the North Caucasian republics), later declined in the regions. Opposition leaders in Moscow were convinced that they had no serious support in the provinces, while regional leaders began to prepare for local elections – mostly for no good reason as it turned out. When the dust settled, only a few of the promised liberties materialized. Between December 15, 2011, when a proposal was made to return to direct gubernatorial elections, and June 1, 2012, when the new rules came into effect, the Kremlin removed or reappointed governors in 25 of Russia’s 83 regions, thus putting off elections there for five years until the new governors’ terms expire. In 13 of those regions, elections were to be held in 2012. As a result, in the autumn of 2012, elections were held only in five regions (instead of 17, as would have been the case if the new rules had come into effect when the political reform was announced). In most of the regions, incumbent governors had a good chance to win reelection, while in regions where the outcome of elections was still in doubt (the Ryazan and Bryansk regions), many experts said the uncertainty was not so much due to opposition activity, as to shady political maneuvers carried out by financial and political clans close to Putin. However, their attempts to compete for governorships were cut short, and the incumbent governors kept their posts in all five regions.

A different strategy was used at the federal level to cement the establishment. While regions demonstrated their readiness to strengthen the political independence of regional leaders, representatives of the central government, on the other hand, had to put up with a sharp decline in their status.

The main moves in this direction were as follows:

- To establish an intentionally weak government led by Dmitry Medvedev (with the possibility of repeatedly raising the issue of the prime minister’s replacement or building up expectations that a “parallel” government would be formed within the presidential administration). Interestingly, at a pre-election meeting with a group of Russian political analysts in February 2012, Putin said he was leaning towards the U.S. political system—not only in terms of bi-partisanship, but also because of the president’s hands-on management.

- Continuing uncertainty over the future of the United Russia Party in view of a possible shift in emphasis to the All-Russia People’s Front.

- Dashed hopes of a higher status for parliament. Instead, it was emphasized that deputies play a purely technical role in ensuring the adoption of decisions that the presidential administration wanted (“mad printer,” as critics call it). Late last year legislators were forced to vote, almost unanimously, for bills that could hurt the deputies’ reputations—not only those of members of United Russia, but also those of opposition parties (for example, the adoption bill).

- Raising the issue of property and other kinds of restrictions for state officials. The restrictions were only partially introduced, but implementing them looked like an attempt to revise the rules of the game, and was accompanied by a selective repression of individual officials suspected of corruption.

- Growing parallelism in the work of the authorities (the possibility of duplicating areas of responsibility for Cabinet members, governors, presidential advisers, and CEOs of state-run companies).

These moves were significant. The risk markedly declined of the ruling class dividing into those who would defend the current regime to the end, and those who advocated a revolutionary scenario (or, at least, were ready to adapt to it). The authorities expanded the timeframe for policy planning (approximately from six months to one year). Moreover, whereas in early 2012 it was unclear whether Putin would remain in office until the end of his term, now the idea that Putin will participate in the 2018 elections is increasingly being discussed. However, the flip side of these moves has been a noticeable decrease in the efficiency of the government. Another problem is a lack of mechanisms for resolving conflicts within the establishment. This is especially dangerous in view of the widespread belief among the elites that the protests are only a continuation of internal games; that specific groups are behind the mass demonstrations or the Pussy Riot performance, which sent their “regards” to each other in this way.

The third task of political reform – easing the rules of the game in “public politics” – was reduced to a liberalization of party registration procedures. Even largely nominal commitments, such as the creation of a public television station or parliament agreeing to consider Internet petitions signed by more than 100,000 people, have been postponed indefinitely. Mikhail Prokhorov’s political suicide and declining expectations for Alexei Kudrin’s political career were followed by a campaign against “foreign agents” and “the Bolotnaya Case.” The opposition A Just Russia party was dismantled; the Communist Party was forced to act in the wake of Putin’s initiatives; and the Liberal Democratic Party was actually included in the ruling coalition (the party received the governorship in Smolensk region).

However, the curtailing of political reform neither caused a decline nor a growth in protests. Organizationally, the Bolotnaya movement was not ready to participate in election procedures – this is why there were actually no confrontations related to the gubernatorial elections.

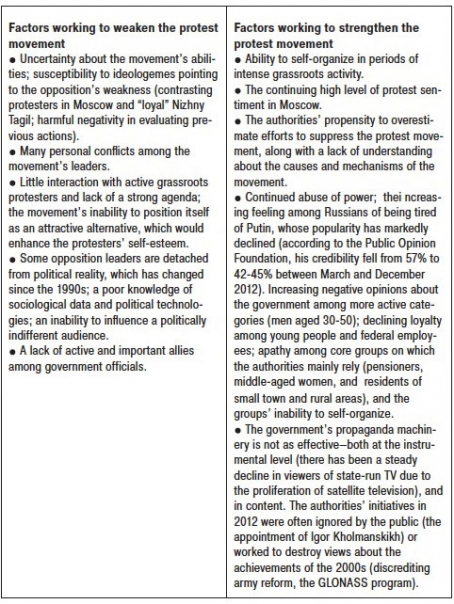

I will refrain from making more general assessments of the protest movement and list some factors from 2012 that may influence the opposition.

Since opposition leaders have failed to attract more people to their movement or bargain with the current elites, the media is gradually emerging as the main driver of opposition sentiment. This somewhat reflects what happened in the late 1980s when the media, rather than socio-political organizations, played the key role in increasing negative sentiment towards the authorities. Putin’s press conference in December 2012 was an indication of this. It was also the first attempt to impose a political debate format on Putin. The press conference was not an attempt to artificially shape public opinion, but a desire to echo audience sentiment (remarkably, sensitive questions were asked by representatives of traditionally loyal media outlets with broad circulation).

If self-esteem grows among the protest movement (which was the case in December 2011-February 2012, and in January 2013), a social upsurge could make up for differences among the protesters and the lack of a coherent strategy, while the absence of well-defined coordination mechanisms could even prove to be an advantage over the “power vertical.” Furthermore, these factors increase the probability of rapprochement between the protesters and the nominal opposition (the Communist Party, A Just Russia, and the “Prokhorov party”), which are now on the other side of the barricades. But if grassroots protests die down, the effectiveness of the opposition will decrease as well.