The migration corridor that has formed between the countries of Central Asia and Russia is one of the largest and most stable in Eurasia and the world. It consists primarily of labour migrants and, according to our estimates, includes from 2.7 million to 4.2 million people – or from 10 percent to 16 percent of the economically active population of Central Asia. That is not only large-scale migration, but it also creates serious political, social, economic, and demographic repercussions for all the countries involved. For example, remittances to Central Asian countries from Russia alone totaled $13.5 billion in 2013. According to the World Bank, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan placed first and second among all countries for remittances as a share of GDP, at 52% and 31% respectively. According to the Federal Migration Service (FMS) of Russia, more than 1.6 million people from Central Asian countries received Russian citizenship in 2001–2011. Because many were labour migrants, returning migrants, and student migrants, as well as refugees, they made a major contribution to Russia’s demographic and labour potential. Labour migration also became a substantial form of economic and political integration between countries of the former Soviet Union, contributing to the formation of the Eurasian Economic Union. That body includes Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan – with Tajikistan as a potential future member. In fact, the combined effect of several factors has contributed to the formation of these labour migration flows from Central Asia to Russia.

Factors Contributing to Labour Migration from Central Asia to Russia

The economic factor. On one hand, in the countries that export migrant workers, the departure of a significant percentage of the of able-bodied population was stimulated by typical “pusher” factors such as eclining production, low salaries, high unemployment, job shortages, increasing poverty, and an idle workforce. On the other hand, certain economic factors in Russia, the recipient of these migrant f lows, serve to make the country even more attractive. These include a large labour market, a diversified economy, a need for workers in many economic sectors and regions, higher salaries, and a better standard of living. The result is a major migration subsystem in Eurasia with Russia and Kazakhstan at its center attracting labour migrants from Central Asian countries. The disparity in salaries among countries in this subsystem provides a clear illustration of the situation. In absolute terms, Russia and Kazakhstan offer the highest average monthly wages, at $689 and $526 respectively. By contrast, Tajikistan offers the lowest average monthly wage at just $81, while the average in Kyrgyzstan is $155. Unemployment levels also largely explain the region’s migration trends. Kazakhstan and Russia had the lowest levels of unemployment in the region in 2013, at 5.2% and 5.5% respectively. At 8.4 percent, Kyrgyzstan had mid-range unemployment, and at 11.6% percent, Tajikistan had the highest. Estimates for some countries, however, were sketchy. The number of unemployed reached 640,000 in Uzbekistan, 471,000 in Kazakhstan, 241,000 in Tajikistan, and 206,000 in Kyrgyzstan, with those numbers generally increasing over time. Rural residents suffered most from unemployment. However, many provide for themselves even without regular jobs by living on the fruits, vegetables, and livestock they raise. Many people in rural areas are not even registered with employment services due to their physical remoteness and the lack of transportation between their communities and employment centers. The lack of jobs in a given area prompts many residents to search for work in the immediate vicinity and nearby countries. The countries of Central Asia are major donors of labour migrants to the Eurasian region, and that migration activity increased significantly in 2000–2010.

Socio-demographic factors. The Russian labour force has been shrinking and growing older ever since the 1990s. That trend deepens shortages on the Russian labour market, intensifies competition for labour resources, and increases labour migration from donor countries. The demographic situation in the Central Asian countries that send the most labour migrants to Russia looks radically different. Projections indicate that by 2050 the working-age population will increase by 6.4 million in Uzbekistan, by 2.8 million in Tajikistan, by 900,000 in Turkmenistan, and by 600,000 in Kyrgyzstan. Even if economic development were to accelerate in the region, those countries could not employ all of their working age citizens. Migration trends among the people of the former Soviet republics grew and transformed between 2000 and the 2010s. In many of those countries, a pervasive stereotype took hold that the only way to succeed in life was to work and earn money in Russia. Many young and middle-aged people in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and other countries prefer working abroad over working or continuing their studies at home. They also follow the example of relatives, neighbors, and acquaintances who have earned enough money from working abroad to buy or build their own homes, cars and other essentials. Further contributing to the increase is the fact that new social and demographic groups have joined the migration – residents of rural regions and small villages, women and youth.

Cultural and historical factors. A migration subsystem has formed in Eurasia based on the socio-economic relations between the countries of the former Soviet Union and the widespread use of Russian as the primary means of communication. Many migrants from Central Asia decide to come to Russia because their knowledge of the Russian language and the Russian mentality greatly increases their chances of finding employment. Most labour migrants in Russia find jobs through social networks, relatives, private intermediaries, and so on. Unfortunately, government agencies and private employment agencies play only a minor role in incorporating migrants into the Russian workforce.

Infrastructural and geographic factors. Despite their location in the heart of Eurasia, the Central Asian states – as the key sources of migrants to Russia – are far more connected to Russia in terms of transportation infrastructure than they are to China, the Middle East, and Western Europe. It is possible to reach Russia from Transcaucasia and Central Asia by rail, road, sea, or air. The number of f lights has increased in recent years, contributing further to labour migration. Many national and regional airlines have opened direct f lights not only to Moscow, but to other major Russian cities as well. Tickets are relatively inexpensive and some Central Asian countries now offer loans for travel to Russia. The availability of affordable transportation and geographic proximity play a significant role in stimulating labour migration from Central Asia and Transcaucasia to Russia.

Political factors. On one hand, many from the Russian-speaking populations of Central Asia and Transcaucasia immigrated to Russia in 1990–2010 for a range of ethno-political factors, including civil war, interethnic conflicts, and domestic nationalism in the 1990s, and in the 2000s–2010s, due to the diminished use of the Russian language and the lack of career opportunities and general prospects in the region. In addition, some Central Asian countries persecute citizens based on their opposition to official policy, political views or sexual orientation. Political conf licts, revolutions, and wars in Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, Uzbekistan, and Ukraine have also prompted migration to Russia, especially among ethnic Russians. On the other hand, the former Soviet republics are making fairly rapid progress toward political and economic integration. The agreement to establish the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) was signed on 29 May 2014, effective 1 January 2015. The EAEU currently consists of five countries – Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia. In addition, it was signed an agreement with Vietnam that would create a free trade zone, and in 2014, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon announced the need to study the economic foundation and legal documents of the EAEU with a view to possibly joining the integrative organization. The citizens of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia can cross the borders between their countries without visas, they also have no need of work permits for employment within the EAEU. Russia also offers visa-free entry for the citizens of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and Moldova. Once in Russia, they have 30 days in which to locate employment and obtain a work patent. By contrast, the citizens of the former Soviet republics of Georgia, Turkmenistan, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia must obtain both work visas and permits.

Trends in Labour Migration from Central Asia to Russia

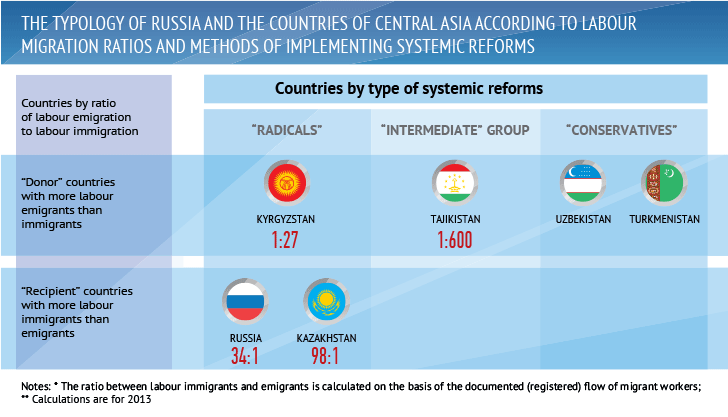

Despite these many factors, labour migration is largely determined by the level of economic development in the countries sending and receiving migrants. Russia and the Central Asian countries fall into three groups in terms of their implementation of systemic economic reforms:

1) radical – Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Russia; 2) conservative – Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan; and 3) intermediate – Tajikistan. “Radical” defines those countries using “shock therapy” to reform their economies. Those in the “conservative” category are more cautious in making the transition to a market economy. The “intermediate” group of countries transformed more slowly than the “radicals” but faster than the “conservatives.” This classification was compared with the classification of countries according to the impact of labour migration. The “radical” states had varying, rather than similar migration ratios: Russia and Kazakhstan are primarily recipients of migrants whereas Kyrgyzstan loses more migrants abroad than it receives. Calculations indicate that, for Russia, the ratio of labour immigration to labour emigration is 34:1, and in Kazakhstan, 98:1. The opposite is true in Kyrgyzstan, where labour emigration exceeds labour immigration 27:1. In Tajikistan, a country in the “intermediate” group, that ratio is 600:1! Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are among the “conservative” migration donor countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1

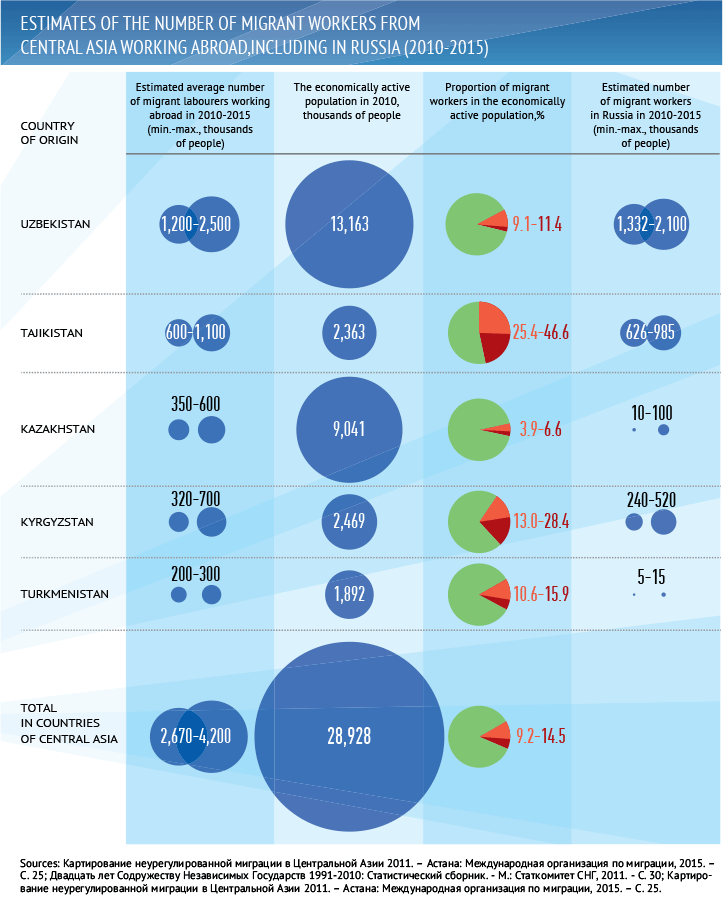

The following general estimates of the number of migrant workers from Central Asia working abroad is based on official statistical data and expert analysis. (Figure 2).

Figure 2

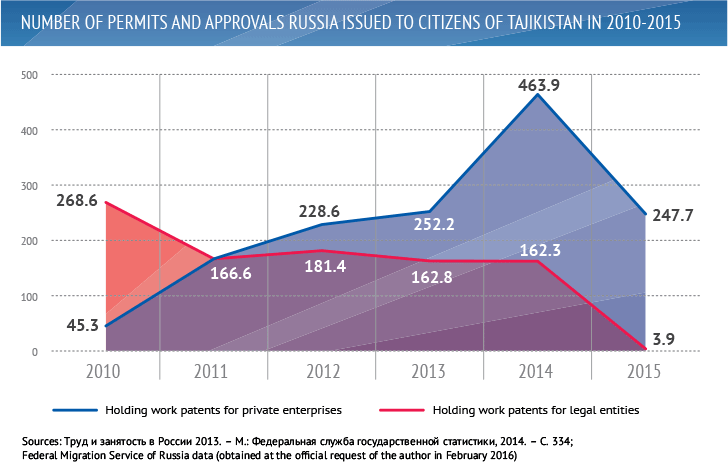

Figure 3

Tajikistan currently provides the second-largest number of labour migrants to Russia after Uzbekistan. According to the 2010 Census, there were 87,000 citizens of Tajikistan in Russia. Of those, 31,500 came to work or study, and of those, 30,500 were of working age. These are undoubtedly low estimates that include only migrants who had been in the country for more than one year. According to the World Bank, in 2010 more than 791,000 citizens of Tajikistan were living abroad, or 11% of the country’s population. A more realistic estimate is that approximately 700,000 Tajik migrant workers live and work in Russia. The FMS reported that 985,000 Tajik citizens were in Russia in early August 2015. The FMS also reported the presence of 626,000 migrant workers from Tajikistan, of whom 162,000 held permits to work in firms and companies, and 464,000 held permits to work for private enterprises (Figure 3).

According to FMS data, Tajik migrant workers laboured in almost every Russian region in 2014, with most concentrated in St. Petersburg, Moscow, the Moscow region, the Khanty-Mansiisk Autonomous District, and also the Sverdlovsk, Kaluga, Samara, Novosibirsk, Tyumen and Volgograd regions.

Tajik migrant workers generally fall into two groups. The first is seasonal workers. Their numbers swell in spring and summer when they come to Russia to work in agriculture and construction. They typically return home in the fall. According to rough estimates, in some Russian regions Tajik citizens comprise approximately 75%-80% of all seasonal migrant workers. The second group is Tajik migrants who remain in Russia for extended periods but who lack legal status. Many work in a wide range of sectors of the Russian economy: services, housing, transportation, and so on. Most Tajik migrant workers are men, although more women have recently begun joining their ranks. The age of the workers depends on the field of employment. For example, in construction, the most difficult work, employers typically hire youth for their greater endurance, physical strength, and robust health. Most agricultural workers are middle-aged.

According to the FMS, in 2010 Tajik migrant workers laboured primarily in construction (44%), trade (14%), industry (11%), services (5%), agriculture (4%), and transportation (3%). By 2014, that picture had changed, with most working in services (42%) and construction (29%). The FMS, however, lacked information concerning 18% of Tajik migrant workers, greatly distorting the statistical findings.

According to a State Statistics Service sample survey on the use of migrant workers, 250,700 Tajik migrants were employed in the “private economy” in 2014 and 145,600 worked for private entrepreneurs. Of the latter, almost one-fourth worked in trade (24%), one-fifth in construction (20%), one-sixth in agriculture (12%), one-tenth in housing services (10%), and 8% in the transportation sector.

Tajik migrant workers have endured poor working and living conditions in Russia for many years, with most living in basements, converted train wagons, or non-residential premises. A number of them lack some of the necessary documents permitting them to live and work in Russia, making them easy prey for labour exploitation and human trafficking.

Despite the daunting personal and professional difficulties, however, as many as 48% of Tajik migrant workers would like to remain in Russia permanently, according to a survey by the Center for Demography and Economic Sociology (CDES) of the Institute of Socio-Political Studies under the Russian Academy of Sciences. Government statistics back up those findings. From 2001 to 2011, 145,000 Tajik citizens received Russian citizenship, many managing to retain their Tajik passports and gain dual citizenship.

The Contribution of Central Asian Migrant Workers to the Economies of Their Home Countries and Russia

The flow of migrant labour into Russia – the largest host country in the region – has created a variety of socio-economic consequences. On one hand, migrants fill many non- prestigious niches in the labour market that have difficult working conditions and that local workers often refuse. In fact, thanks to migrant workers, entire economic sectors grow and develop in the receiving countries. A good example is the growth of the construction industry in Russia’s largest cities, largely due to the use of cheap labour from abroad. Federal Migration Service Director Konstantin Romodanovsky noted that migrant labour accounted for 8% of GDP in 2011. In addition, migrant workers contribute to the Russian economy by spending part of their incomes on meals, lodging, and some services. Surveys of migrant workers indicate, however, that they must take great pains to economize, especially on food, in order to send money home. They scrimp on food, eating mostly bread, milk, noodles, rice, etc., rarely purchasing meat, fruit or vegetables. They prepare their own meals, often pooling their savings to feed several people, and spend almost nothing on entertainment, clothing, or shoes. According to official estimates, migrant workers in Russia earned cumulative net wages of $10.5 billion in 2013 after taxes and travel expenses. Assuming they spent 15% of that sum on daily expenses, revenues to the Russian economy total about $1.6 billion.

On the other hand, labour migration also has a number of negative consequences for host countries: it stimulates the growth of the shadow economy, depresses wages and leads to the formation of closed ethnic enclaves. Studies indicate that almost every sector of the economy makes use of migrant labour. In many, a practice has developed of listing Russian employees on the books when migrants are actually doing the work. One illustrative example is the way commercial and apartment building owners employ migrants to perform routine maintenance and concierge services at rock bottom rates, but list them as Russian employees drawing much higher salaries, pocketing the resultant savings. Serious social and humanitarian problems also exist. Migrant workers live under poor conditions, receive much lower wages, and suffer exploitation at the hands of employers and violations of their human rights from all quarters. In effect, it amounts to the formation of a segment of forced labour in certain sectors of the Russian economy. And due to the depressive effect migrant labour has on the price of labour, local workers often refuse to look for employment in those sectors, and employers lose interest in recruiting them.

Russian businesses from small to large simply desire cheap labour, and with few exceptions, do not invest their resultant excess profits into social projects aimed at integrating migrants into society. Мoreover, such employers assume no responsibility for providing health insurance or access to social services for migrant employees. Instead, the government carries the primary burden for caring for migrant workers and their families, in the form of education, health care, and pensions. For example, childbirth by female migrant workers from Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan alone cost Moscow approximately 5 billion rubles in 2011. Studies show that 10–20% of migrant workers come to Russia with their children, more than 90% of whom attend public schools. A lack of statistics makes it difficult to study the issue of education for the children of migrant workers, although some figures do exist: such children comprise 10% of all students in Moscow, 12% in the Moscow region, and 3% in St. Petersburg. Estimates indicate that the children of migrant workers could comprise up to one-third of all Russian school students within 8–10 years if the current migration policy remains unchanged. One of the main problems, however, is the lack of a unified state program aimed at integrating those students socially and culturally, and helping them learn Russian and adapt to the Russian way of life. Russia’s extensive body of legislation contains absolutely no guidelines for the education of migrant children.

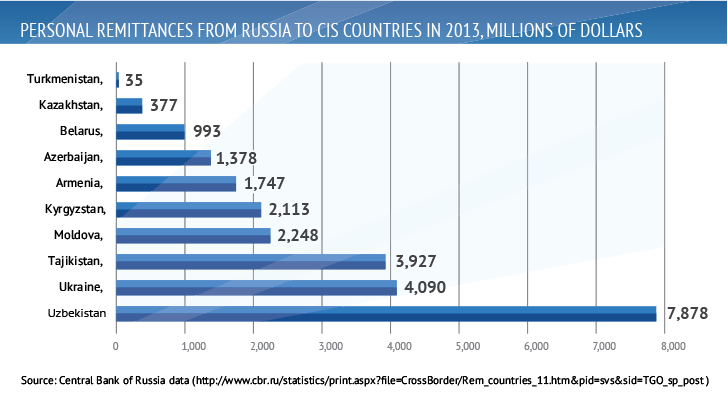

The large-scale flow of labour migrants also has mixed consequences for the countries of Central Asia. The most obvious positive result is the large quantity of money that migrants send home. The negative consequences are often hidden or delayed and include both the economic effects and the social costs of migration. Because the Central Asian countries provide most of the migrant workers in Russia, those states are also the recipients of most of the remittances sent from Russia. All Central Asian countries were recipients of such funds in 2013, with Uzbekistan in first place, receiving $7.9 billion, Tajikistan in third place with $3.9 billion, Kyrgyzstan in fifth place with $2.1 billion, Kazakhstan in ninth place with $377 million and Turkmenistan in 10th place with $35 million. (Figure 4)

Figure 4

The money that members of the Tajik diaspora send home plays a major role in the socio- economic development of Tajikistan as a whole, and of specific regions and households. Tajik migrants sent home $2.1 billion in 2010 and $4 billion in 2013 – or approximately 52% of that country’s GDP. According to the Central Bank of Russia, remittances to Tajikistan only from Russia alone amounted to $4.2 billion in 2013. By some estimates, the sharp devaluation of the ruble in 2014–2015 caused the average and absolute value of remittances from Russia to Tajikistan to fall by 40%-50%.

These remittances affect the socio-economic development of Tajikistan in several ways. First, there was a close connection between the volume of money transferred and Tajikistan’s economic growth from 2000 to 2014, and especially after 2005, when the period of “restorative growth” in 2000–2004 had ended and when such remittances had minimal impact. Overall, the increasing size of such remittances stimulated an increase in the country’s GDP.

Second, the money transferred into the country did not lead to significant investment in local production. In addition, migrants and their families invested only minor sums in developing small businesses such as bakeries, cafés, small stores, and so on. In fact, the wire transfers stimulated growth in practically only one sector of the economy – construction – with many Tajik migrant workers using their earnings to remodel their homes, build new ones or purchase apartments.

Third, the money transfers by migrant workers stimulate additional consumption, as Tajik citizens began spending more on food, consumer goods, housing, and education. Goods and services in Tajikistan that are subject to an 18% VAT in Tajikistan (and 12% in Kyrgyzstan) serve to augment state coffers. In both Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, VAT fees account for approximately one-half of all tax revenues. In addition, the increase in remittances to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan prompted an increased demand for imported goods, primarily Chinese, resulting in greater market trade for the countries of Central Asia.

Fourth, the flow of remittances from abroad spurred the development of local “social initiatives.” For example, locals in many mahallla in Tajikistan took the initiative to collect funds for the repair and construction of public places, buildings, water and gas systems, and various road-related structures. Such initiatives often compensate, however, for the complete lack of government initiatives and incentives.

CDES and Tajik scholars conducted a study in the city of Khujand, Tajikistan, in the summer of 2008 on the use of money transferred into the country. They surveyed 200 households receiving remittances from abroad.

The study found that more than one-third (37%) of Tajik households received money transfers from spouses working in Russia; approximately 28% received money from children or grandchildren;, approximately 16% from parents; and approximately 14% from more distant relatives. Money sent by relatives remains the primary “channel.” Migrant workers are usually married men with children who work abroad in order to support their families. A survey found that 24% of households with migrant workers consist of at least five people, 22% have at least four, and 19% at least six. Further, 21% of such households have two minor children, 18% have three, and 9% have four. Many such families are large and have many children.

Most households (65%) receive remittances from abroad once per month, and approximately one-fourth every few months. Approximately 9% of households surveyed received such funds several times per month.

Many families in Tajikistan and other countries of Central Asia are now very dependent on money sent from abroad, and primarily from Russia. One Tajik study found that 12% of the income of even the most prosperous segment of the population consists of money transfers from abroad. Of the households we surveyed, 45% said most of their incomes come from remittances, 39% said they constituted one-half of their income and 15% said such funds represent less than one-half of their income.

Many studies show that households spend such remittances on daily expenses, thus spurring short-term growth in economic sectors producing such everyday goods as food and services, as well as in housing construction. According to our study, 74% of households in Tajikistan use money transferred from abroad to buy food, indicating that labour migration focuses primarily on feeding families. In addition, 34% of families use that money to buy clothing and 31% for medicine and medical treatment. Housing-related needs represent a more substantial investment of those funds. The same study found that 26% of households receiving money from migrant workers in Russia spent money on home construction or remodeling. Approximately 45% of those surveyed also paid for education – another more long-term use of those funds. Approximately 23% of households have savings, most of whom deposit that money in bank accounts.

Although the countries of Central Asia enjoy certain short-term benefits from the export of labour, it is obvious that they would see greater revenues if those workers produced the same goods and services at home. The most effective and promising model of economic development for the countries of Central Asia is one based on increased manufacturing for export, that in turn would create more jobs and gradually reverse the migration trend. Labour migration abroad gives countries an opportunity to adopt new models of economic development. In this regard, the countries of Central Asia should work to attract uncommitted funds to their economies in order to stimulate entrepreneurial activity among their domestic populations.

Our survey also asked household members in Tajikistan under which conditions they would be willing to keep their money in banks – that is, to invest in developing the national economy. It turned out that 54% of respondents were unwilling, although approximately one-fourth said they would do so if annual interest rates increased and 11% of respondents – if the government guaranteed the security of their deposits. This indicates not only that ordinary Tajik citizens are unwilling to invest their money in the larger economy, but also that the government lacks policy on the issue. Instead, state policy continues to focus on the export of labour – that produces only short-term benefits for the country.

Entrepreneurship and small business are important engines of the economy. The money that migrant workers send home represents the “initial conditions” by which part of the population could realize that potential. The survey found that more than one-half of all households are ready to invest funds received from migrant workers abroad to start and develop their own business ventures. One-fourth of respondents said they wanted to open their own store or a stall at the local market, approximately 8% wanted to buy a car as an aid to earning money, 6% were ready to launch small-scale production, and 3% wanted to open a cafe or restaurant. Of course, the countries of Central Asia, including Tajikistan, must use the entrepreneurial potential of their population. It would make sense for them to create favorable tax policies that would stimulate the families of migrant workers to invest money in their own businesses. Russia might also benefit from the entrepreneurial potential of migrant workers located in the country.

The survey in Tajikistan showed that citizens are more willing to invest in local infrastructure projects than in banks. Approximately 33% of households are willing to contribute funds for the construction of water, sewer, or gas lines in their villages; approximately 31% for road repair or construction; 16% for the construction or repair of schools; approximately 11% for the construction or repair of hospitals; and 3% for the construction or repair of community centers. Only 1.5% of respondents said they would not contribute money to local projects.

Research in Tajikistan showed that the households of migrant workers hold significant socio-economic potential – if properly administered – for resolving social issues at the grassroots. The governments of Central Asia have not fully appreciated or made effective use of that potential for the development of their states as a whole, or of specific regions or villages in particular. Money transferred from abroad is primarily used to pay for food, the purchase or remodeling of homes, consumer goods, weddings, and funerals. Although that partly relieves social tension in society, it means the government essentially shifts its social welfare obligations onto migrant workers. They continue to invest too little in developing local infrastructure such as water and gas lines, roads, and so on, or into small business, entrepreneurship, or manufacturing. Thus, remittances, unfortunately, continue to play only an insignificant role in the medium-term economic development of countries exporting migrants.

Labour migration lowers the unemployment rate of the home countries, creating a strong “social welfare assistance” effect, and the money those migrant workers send back eventually helps fill government coffers through taxes on consumer goods purchased with those funds – thus producing the so-called “short money” effect.

It is worth noting that anyone developing a business in Central Asia faces numerous obstacles. First, local administrations or those higher up often discourage local initiative, making projects unfeasible with unreasonable demands for approvals and permits. As evidence, in many UNDP projects in Tajikistan, the organization’s role is limited to simply assisting in talks with the authorities. Second, local governments differ greatly throughout the region. In Kyrgyzstan, local government is highly decentralized, while Tajikistan retains a strong power vertical in which local leaders are “selected by agreement.” Uzbekistan has a similar power vertical, but devolves a great deal of authority to mahalla committees.

Models for Regulating Labour Migration in Central Asia

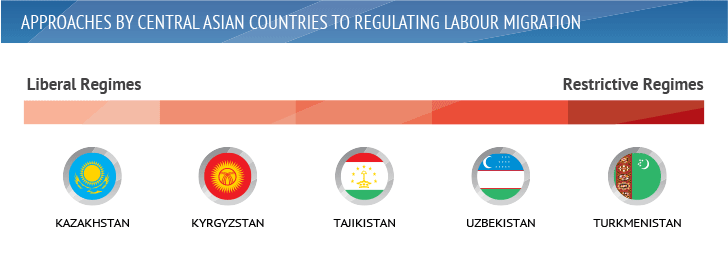

With the exception of Kazakhstan, the countries of Central Asia are migrant labour donors. Labour migration out of the region results from similar factors and has common features. Yet, those countries regulate labour migration to different degrees. The regime in Kazakhstan takes the most liberal approach and that in Turkmenistan the most controlling, with the remaining countries falling along a spectrum in between. (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Kazakhstan pursues a liberal but passive method of regulating labour migration that aims at reducing the outflow of labour resources by stimulating the return migration of Oralmans (ethnic Kazakhs) and students who have received their education abroad, and by attracting a limited number of foreign workers according to established quotas. Official Kazakh policy has undergone a “pivot” in recent years toward prioritizing a reduction in labour emigration. In particular, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev announced the Kazakhstan-2050 strategy in December 2012 that details seven long-term priorities of the government – among them, development of the country’s human potential. Official strategic documents of the government have also recognized the need to prevent the emigration of the working age population. For example, Kazakhstan’s Comprehensive Plan for 2014–2016 states a long-term goal of retaining the country’s skilled workforce by providing its members with priority access to Kazakhstan’s labour market. That is accomplished by establishing quotas on foreign workers and requiring that employers give preference to hiring Kazakh workers to fill job vacancies.

Kyrgyzstan pursues a liberal but active method of regulating labour migration that is arguably the most developed among the countries of Central Asia. The primary strategic goal of that policy is to make use of labour migration to further the country’s socio-economic development. Whereas, in the 2000s, that policy sought to bring the f low of migrants under government oversight, protect the rights of migrant workers living abroad, and encourage the transfer of earnings back into the country, by the 2010s the government began focusing on repatriating migrant workers, enlisting them for socio- economic development, and reducing the number of skilled Kyrgyz professionals working abroad. To a great extent, changing the strategic goal of regulating labour migration prompted the Kyrgyz authorities to recognize the negative social and demographic consequences of mass labour emigration.

By contrast, the government of Uzbekistan exerts nearly total control over labour migration, prohibiting migrant workers from leaving the country, preventing unorganized labour migration, and doing its utmost to organize and regulate that migration. The authorities exercise control through legal, administrative, and economic means.

Turkmenistan, meanwhile, takes an approach unique in Central Asia of exercising absolute control over labour migration. Essentially a closed country blocking immigration by foreigners and emigration by its own citizens, Turkmenistan exercises nearly total state control over the flow of migrants.

In Tajikistan, the state plays a significant role in regulating labour migration. As a typical source country for migrant labour, in 1988 Tajikistan became one of the first states in Central Asia to adopt a Concept for State Migration Policy. On 9 June 2001, it also adopted the Concept for Labour Migration by Tajik Citizens Abroad, No. 242 that effectively encouraged unemployed citizens to become migrant workers in other countries. That document states: “In the context of an overabundance of manpower and limited financial resources to create new jobs, approximately 30% of the unemployed population can emigrate as labourers. The purpose of the migration policy of Tajikistan concerning labour emigration is the social and legal protection of Tajik citizens temporarily working abroad, the regulation of migration flows, the prevention of illegal immigration and the adoption of laws governing the migration process.” Developing the concept of labour migration in December 2002, the government adopted the Program for Tajik Migrant Workers Abroad for 2003–2005 that tasked relevant ministries and agencies with more actively stimulating labour migration. In July 2004, Tajikistan adopted a law “On combating human trafficking,” after which the state developed a program for labour migration by citizens of Tajikistan for 2006–2010. In 2011 it adopted the most recent such policy, covering the period 2011–2015. In it, the state acknowledges for the first time the impact of labour migration on the economy and the need for a fundamentally new approach to the regulation of labour migration in Tajikistan. That strategy aims primarily at creating the legal and institutional mechanisms for regulating migration and the provision of services to migrants and their families, and to a lesser extent at providing specific services to migrants. Unfortunately, the plan for implementing the National Strategy on Labour Migration contains no specific figures or indicators for evaluating its effectiveness by, for example, measuring the number of migrant workers benefiting from the strategy or the impact of the strategy’s measures for upholding the rights of migrant workers. Tajikistan adopted a new law “On combating human trafficking” in July 2014, but despite the country’s vast legislative framework for regulating labour migration, Tajik citizens are among the most poorly protected labour migrants of Central Asia while residing in the recipient countries of Russia and Kazakhstan.

Originally, a separate Migration Service of the Tajik government was responsible for implementing migration policy, but it became part of the Ministry of Labour, Migration, and Employment in 2013. According to Resolution No. 390 of 4 June 2014, the Migration Service is mandated to deal with only three types of migration: labour, domestic, and environmental. The Migration Service headquarters are located in Dushanbe. Bureaus of the Migration Service were established in the Sughd and Khatlon regions and the city of Dushanbe. Departmental offices were set up in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, and departments and branch offices were also established in the regions and cities of Tajikistan. The Migration Service also offers a network of Pre-Departure Centers for Counseling and Training Migrant Workers in Dushanbe, Khorug, Khujand, Vahdat, Qurghonteppa, Kulob, Panjakent, Tursunzode, Isfara, and the Rasht region. Resolution No. 392 also calls for opening a Moscow office of the Tajik Ministry of Labour, Migration, and Employment devoted to migration. That office is primarily tasked with working with embassies and consulates to protect the rights and interests of Tajik migrant workers, cooperating with the relevant Russian authorities in the area of migration, carrying out measures for implementing international treaties on migration to which Tajikistan is a signatory, and analyzing opportunities for Tajik labour migrants in the Russian labour market.

Possible Scenarios for Changing Labour Migration Flows from Central Asia

Of course,the economic crisis in Russia in 2014–2015 had a negative impact on migration from Central Asia. The decline in production caused a reduction in the employment of migrant workers because they are the first to lose jobs in a downturn. The devaluation of the ruble led to a substantial 30 percent to 50 percent decrease in the volume of funds that migrant workers sent home. Finally, some migrant workers who had lost their jobs in Russia began returning home to Central Asia. Many are unable to find work there either, leading to a rise in unemployment, social tensions, and crime. Several interviews with migrant workers confirm this.

Interview 1. Migrant worker from Dushanbe (Tajikistan).

Yes, we want to leave. Almost everyone wants to. More than half have already left. My brother left with his family and they had lived in Moscow since 2004. What can we do? We have no money, but now with the new rules, we have to practically work for free. I worked in construction and earned a good salary – about 40,000 rubles [per month], but I transferred the money [home] in dollars. We don’t have any debts: I paid off the last of the debt last month. We borrowed $1,000 dollars and paid back $150 more [in interest]. We had to do some remodeling. That is a lot of money for us. My brother is looking for work in Tajikistan now, but he hasn’t found anything yet. But things are still better in my homeland than here. [1]

Interveiw 2. Ansur (29 years old), migrant worker from a village near the city of Qurghonteppa (Tajikistan).

Because of the ruble’s sharp drop, salaries in Tajikistan and Russia are almost equal now. I worked odd jobs in the Moscow region, built dachas. The pay varied, but I usually earned 30,000–40,000 [per month]. Sometimes the pay came late, but not for long, and they always paid in the end. But before, 30,000 rubles was almost $1,000, and now it is less than $500. That is about the same as salaries in Tajikistan, although there’s less work available. It used to be possible to live in Tajikistan for three or four months on $1,000. That’s not possible now, and prices in Tajikistan are 1.5–2 times higher now also. [2]

Studies indicate, however, that this trend did not last long because the first wave of the economic crisis in Russia coincided with the seasonal migration of temporary migrant workers who usually return home in winter. They began returning to Russia in spring 2015, although the devaluation of the ruble has made it less lucrative to work in this country. Moreover, Russian migration policy is unstable and has recently become considerably stricter. Russia began cracking down on illegal migration in 2014 by barring entry to foreigners who have broken the law. According to the FMS, in 2015–2016 1.6 million foreigners were barred from entering Russia under that law. That led to higher social tensions in the countries of Central Asia when they were already struggling with economic crises and serious job shortages. There are even reported cases of migrant workers committing suicide because they were barred from entering Russia and could not find work at home.

In addition, the cost of filing for a work permit, or “patent” in Russia increased significantly in 2015, prompting many migrant workers from Central Asia to work without one – thus shifting them into Russia’s “shadow economy.”

Of course, many experts anticipate a more upbeat scenario in which the Russian economy stabilizes and the influx of migrant workers from Central Asia resumes. In fact, the demographic situation gives every reason to believe this will happen. Projections indicate that Russia will experience labour shortages in the medium term, even while local populations grow rapidly in Central Asia. For example, the population in Uzbekistan reached almost 31 million in 2014, with the able-bodied population of persons aged 18–60 reaching 18 million. In Tajikistan, the birthrate reached 3.7 children per woman of childbearing age and the overall population totaled 8.1 million in 2014. In Turkmenistan, the birthrate was 2.1 children per woman of childbearing age and the population was 5.1 million in 2013.

The United Nations forecasts that the population of Tajikistan will swell to 10.4 million by 2050, including a working age population of 6.6 million. The population of Turkmenistan will grow to 6.8 million, and of Kyrgyzstan to 6.7 million. By contrast, the UN predicts that by 2050 the population of Russia will decrease by 30 million, to 112 million. The population of Kazakhstan could shrink considerably over the same period, decreasing by 1.7 million to 13.1 million. The average age in Russia will also increase, creating more pensioners even while the number of youth and working age citizens declines. This will lead to an increased burden on the government to provide pensions, healthcare, and social programs. And while the populations in Russia and Kazakhstan age and shrink, the exact opposite is happening in Central Asia. There, by 2050, the working age population will increase by 6.4 million in Uzbekistan, 2.8 million in Tajikistan, 900,000 in Turkmenistan, and 600,000 in Kyrgyzstan. Even if economic development were to accelerate there, those countries could not employ all of their working age populations. It is very likely that Central Asian countries will remain the primary donors of migrant labour to Russia and Kazakhstan over the medium term.

Migrant workers from Central Asia continue coming to Russia, and to a lesser extent, Kazakhstan, due to labour markets that offer much greater opportunity than those of other nearby countries. Even the higher wages available in Middle Eastern countries, Turkey, and South Korea do not outweigh the disadvantages of their stricter demands for high-quality work, the difficulty of obtaining a work visa, the need for specialized knowledge and command of the language, and the tougher attitudes of employers. However, if those countries work harder to attract migrant workers from Central Asia, if attitudes in Russia toward migrant workers worsen, and if the economic crisis continues, the direction of the current migration flows could change. In theory, the flow of migrant workers from Central Asia could shift toward the Muslim countries of the Middle East (Turkey and Iran) and the Persian Gulf (Qatar, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia), or toward East Asia (South Korea). For example, Saudi Arabian authorities announced the possibility of recruiting migrant workers from Tajikistan, which could have negative consequences by contributing to the spread of religious fundamentalism and radicalism.

For example, according to Karomat Sharipov, chairman of the Tajik Labour Migrants NGO, “Many workers from Tajikistan would like to leave Russia. This trend is due not only to the exchange rate of the ruble against other currencies. Migrants must pay 30,000 rubles to pass the test on Russian language, history and laws that become a requirement on 1 January

2015. That, together with the weakened ruble, had a strong impact on incomes and the ‘start-up price’ for going to work in Russia – also taking into account the price of tickets and obtaining a work permit. Many Tajiks have outstanding debt at home in dollars and with high interest rates. What can they do to pay that down?” he asked. “They must look for work in other countries.” [3]

Does Russia come out the winner in this situation? Most likely, it comes out the loser, not only economically, but also geopolitically.

References And Sources:

1. Акрамов Ф.Ш. Демографическая ситуация и трудовая миграция из Таджикистана в Россию// Практика привлечения и использования иностранной рабочей силы в России: тенденции, механизмы, технологии: Материалы научно-практической конференции (16–17 октября 2006 г.)/ Отв. ред. С.В. Рязанцев. – М., 2006.

2. В России наблюдается сезонный спад трудовой миграции из стран Центральной Азии (http://migrant.ferghana.ru/newslaw/в-россии-наблюдается-сезонный-спад-тр.html)

3. Великий исход мигрантов [http://www.gazeta.ru/social/2015/01/20/6381253.shtml]

4. Выступление Президента Республики Казахстан, лидера нации Назарбаева Н.А. «“Стратегия Казахстан – 2050”: новый политический курс состоявшегося государства» (онлайн речь) (http://www.akorda.kz/en/page/page_poslanie-prezidenta-respubliki-kazakhstan-lidera-natsii-nursultana-nazarbaeva-narodu-kazakhstana/

5. Двадцать лет Содружеству Независимых Государств 1991–2010: Статистический сборник. – М.: Статкомитет СНГ, 2011.

6. Ивахнюк И.В. Евразийская миграционная система: теория и политика. – М.: МАКС Пресс, 2008.

7. Картирование неурегулированной миграции в Центральной Азии 2011. – Астана: Международная организация по миграции, 2015.

8. Рязанцев С.В. Вклад трудовых мигрантов в рождаемость в России: социально-демографические эффекты и издержки (http://www.rfbr.ru/rffi/ru/popular_science_articles/o_1894211)

9. Рязанцев С.В. Масштабы и социально-экономическое значение трудовой миграции для стран СНГ// Практика привлечения и использования иностранной рабочей силы в России: тенденции, механизмы, технологии/ Материалы научно-практической конференции (16–17 октября 2006 г.). – М., 2006.

10. Рязанцев С.В. Работники из стран Центральной Азии в жилищно-коммунальном секторе Москвы (рабочий доклад). Рабочий доклад, МОТ: Субрегиональное бюро для стран Восточной Европы и Центральной Азии. – М.: МОТ, 2010 – С. 12 (www.ilo.org/public/russian/region/eurpro/moscow/projects/migration.htm)

11. Рязанцев С.В. Трудовая миграция в странах СНГ и Балтии: тенденции, последствия, регулирование. – М.: Формула права, 2007.

12. Рязанцев С.В., Горшкова И.Д., Акрамов Ш.Ю., Акрамов Ф.Ш. Практика использования патентов на осуществление трудовой деятельности иностранными гражданами-трудящимися мигрантами в Российской Федерации (результаты исследования). – М.: Бюро МОМ, 2012.

13. Статистика СНГ: Статистический бюллетень. – № 15 (366), август 2005.

14. Труд и занятость в России 2013. – М.: Федеральная служба государственной статистики, 2014.

15. International Migration Outlook 2013, Paris, OECD Publishing, 2013 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2013-en)

16. Migration and Remittances Fact book 2011, 2hd Edition, Washington DC, The World Bank, 2011.

17. Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook, April 14th 2014, The World Bank (http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPROSPECTS/Resources/334934–1288990760745/ MigrationandDevelopmentBrief22.pdf )

18. Ryazantsev S., Trafficking in Human Beings for Labour Exploitation and Irregular Labour Migration in the Russian Federation: Forms, Trends and Countermeasures, Stockholm, ADSTRINGO, Baltic Sea States Council, 2015 (http://www.ryazantsev.org/book1–16.pdf )

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.