Abstract

In the 1990s-2000s unilateral sanctions were viewed primarily as a reactive, often tactical, policy tool applied to weaker countries, or as an auxiliary strategic instrument (greatly inferior in importance to military-political ones). But today the status of sanctions has risen significantly. From a formal point of view, they are still ineffective since in most cases they do not lead to the achievement of declared political goals. However, in the past two to three years sectoral sanctions against Iranian and Russian companies and their partners, and technological ones against China (in addition to the trade war) have been expanded, which increasingly turns them from a “noisy” but ineffective tactical instrument into one of the pillars of strategic deterrence. This article examines three interrelated developments that have occurred in recent years: unilateral sanctions as such, their effects, both direct and concomitant (collateral damage), and, finally, reactions to them. Our analysis suggests that formal and informal unilateral sanctions will be intensified both in the short term and in the medium term of three to five years. However, within the next ten to fifteen years, as the international political and economic system becomes increasingly mosaicked, even their immediate effects and consequently their importance will be smoothed over, while the cost of international cooperation will increase. In other words, sanctions will become less ruinous, but fostering “fortress to fortress” bonds will become significantly more expensive and will require large investments in “building trust” with new partners. For Russia, this means transforming the strategy of survival under sanctions, launched five years ago, into a strategy of development under sanctions.

Keywords: unilateral sanctions, Russia, China, multipolarity, geo-economics

INTRODUCTION

The term ‘sanctions’ has become so widespread, and their use has expanded so much that one study can hardly cover all relevant trends pertaining to this phenomenon. So, the article focuses on formal unilateral sanctions understood herein as restrictive measures with economic effects, which pursue political objectives and are introduced in circumvention of the UN Security Council.

Thousands of unilateral sanctions are imposed every year against individuals, companies, NGOs, and less often against states, as formal measures initiated mainly by the United States and less often by the EU and other U.S. allies (Australia, New Zealand, Japan, etc.). In 2018 alone, the United States imposed sanctions against approximately 350 individuals, 300 entities, 49 vessels and 32 aircraft in addition to about 700 individuals and entities associated with Iran that were subjected to sanctions when the U.S. seceded from the JCPOA (Dentons, 2019).

There are also numerous informal restrictive measures actively used by countries, such as Russia and China, which do not recognize unilateral sanctions and consider the UN Security Council the only legitimate authority empowered to impose sanctions. But the most significant and visible changes are occurring in formal sanctions practices and their effects, because informal restrictive measures rely on traditional tools, mainly various non-tariff barriers in trade in goods and services like Russian measures against Georgian and Moldovan wine (Newnham, 2015) and Turkish tomatoes (Özertem, 2019), or China’s sanctions against its neighbors (Reilly, 2012).

In this article we will focus on the evolution of formal unilateral sanctions in the post-bipolar period, unless stated otherwise. It is these sanctions that are used today against Russia and, gradually, against China. During the Cold War period (1945-1991), sanctions as an element of the “economic Cold War” were incorporated into the structure of bipolar confrontation and used against the Soviet Union and other socialist countries (through the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM)) as well as against China. Although in the post-bipolar period sanctions have not lost relevance in the foreign policies of the United States and other players, but on the contrary have gained greater importance, this kind of influence and, above all, the external conditions for its use have changed significantly.

The hypothesis of the study is that although the legal approaches to the use of sanctions in the United States and other countries, which impose formal unilateral restrictions, remain intact, changes in their nature and external conditions for their use require new responses to sanctions challenges.

The purpose of the study is thus to determine necessary qualities for the Russian strategy of responding to sanctions and related challenges as sanctions instruments and external conditions for their use keep changing quite rapidly.

Within the framework of this article, we will consistently solve three tasks: first, we will systematize key changes in sanctions policy as such; second, we will assess trends in reaction to such sanctions, and, accordingly, to qualitative changes in their effects. Finally, part three will focus on Russia’s sanctions policy and assess its potential in the international context considered.

EVOLUTION OF UNILATERAL SANCTIONS

Sanctions represent an ever-changing phenomenon of international life. Even if sanctions are formally imposed in the same way as five or twenty-five years ago, there are a number of signs indicating that they have undergone fundamental changes.

Stakeholders of Sanctions Agenda

The most visible shift concerns the target audience, which has expanded significantly and become more privileged by international standards. Unlike in 2014, when the imposition of sanctions against Russia was considered an exceptional situation, today sanctions are more and more often viewed as a “new normal” of international relations.

In the 1990s, sanctions were used mainly against small countries with a view to changing their political regime or behavior in the international arena, or against international drug cartels (for example, the international campaign “La Lista Clinton,” launched by the United States in 1995). In the early 2000s, a fierce sanctions war was started against a new player—international terrorist organizations (Hufbauer, Schott and Oegg, 2019)—by means of financial sanctions effected through the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the U.S. financial intelligence services’ access to the SWIFT worldwide interbank financial telecommunication system (Zarate, 2016).

Sanctions were also imposed against great powers: India (for nuclear weapons) and China (after the events in Tiananmen Square), but the former were of limited severity, and the latter, imposed simultaneously by the United States and the EU, were subsequently lifted except for the arms embargo. These sanctions were primarily a disciplinary measure rather than a means of deterrence against a major power.

The first major player to face so-called all-out, or comprehensive, sanctions was Iran in 2010, but the tendency to make sanctions against that country global dates back to the 1990s. The new sanctions were initiated by the U.S. which had previously been imposing unilateral restrictions on Iran for more than 20 years. In the 2000s the grip was tightened further: the first UN Security Council resolution was adopted in 2006 (No. 1696), followed in the subsequent three years by four more: No. 1696, No. 1737, No. 1747, and No. 1929, the toughest one of which made the sanctions complete. Unilateral sanctions, including the severest ones, such as the disconnection from the SWIFT system, broadened their coverage, but it was only after the U.S. resolution that such a powerful and effective anti-Iranian coalition was built (Timofeev, 2018b; Ji-Hyang and Lee, 2013).

Then, in 2014, sanctions were imposed on Russia, and over the following five years they have transformed from mainly the first “disciplinary” packages adopted in the spring of 2014 into systemic and deterrent ones. According to leading experts, the next great power to be subjected to the intense pressure of sanctions will be China (Drezner, 2018a). In fact, it has already been facing individual sanctions and an arms embargo since the 1990s. In part, Chinese companies fall under sanctions not for their “success” or market share, but for violating U.S. sanctions against Iran. That is how ZTE was slammed after repeated warnings of sanctions for the supply of prohibited equipment to Iran. Similar arguments were stated as the official reason for sanctions against Huawei, although the arrest of its top manager as part of these measures was quite unprecedented (The company’s vice president and CEO’s daughter was detained in Canada at the U.S. request) and only proved the political nature of the Huawei case (Bajak and Liedtke, 2019).

Second, the risks of so-called “secondary” sanctions for the EU, India, Korea, Japan, China and other countries have increased in recent years (Geranmayeh and Rapnouil, 2019). Some companies and banks in these countries, mainly European ones, regularly fall under American sanctions and have to pay fines for cooperation with sanctioned companies and countries. There are about 150 Chinese companies on the SDN lists. For other countries, the risk of getting on such lists may serve as a restrictive factor in making investment or trade decisions. Complaints about informal U.S. pressure have been repeatedly made at Chatham House Rule meetings by Korean and Japanese investors who are potentially interested in cooperation with Russia. A former OFAC employee, Juan Zarate, writes openly about this exhortative practice with regard to Iran (Zarate, 2016). However, it would be an exaggeration to say that such risks are a universal constraint for business. In the absence of UN Security Council resolutions, dozens of European, Korean, Chinese, and Indian corporations worked in Iran in the 2000s, and the American ban on Iranian oil import is violated nowadays, too (Singhi, Wong, and Lu, 2019). A vivid example is the Nord Stream-2 project, in which Russia is the political target of sanctions, but any company that directly contributes to its implementation, i.e. European participants, may face sanctions as well.

Third, in the last two to three years, the number of countries using formal sanctions has increased. Apart from traditional sanctioning powers—the United States and the European Union—sanctions have become more widespread in the Middle East, largely due to Saudi Arabia’s policy (Cordesman and Hashim, 2018): it has persuaded four Arab countries to impose sanctions on Qatar, and used individual sanctions against Canada (Drezner, 2018). In other words, we are witnessing the proliferation of formal sanctions, even though earlier formal sanctions were an exclusive foreign policy tool designed mainly to ensure the unavoidability of punishment, which could be done, at least partly, only by global actors.

Sanctions Toolkit

During this period, the sanctions toolkit has also changed to include a wider range of measures. Traditional trade sanctions, which have been in existence since 5 BC, have changed in two principal ways. First, there has been a shift from comprehensive sanctions aimed at blockading individual countries to so-called targeted, or “smart sanctions” (Drezner, 2011). It is worth mentioning that the new model of sanctions began to be used only after comprehensive and subsequent sanctions against Iraq (authorized by a UN Security Council resolution) had resulted in the death of several hundred thousand people from hunger (Koc, Jernigan and Das, 2007; Alnasrawi, 2001). Such blockades were considered inhumane (Kozal, 2019), so they had to be abandoned in favor of targeted sanctions against companies or individuals. Damage from such sanctions can be either symbolic (for example, the freezing of U.S. dollar assets or denial of entry to individual politicians and civil servants) or comparable with the damage from comprehensive sanctions, if, for example, the central bank of a particular state is disconnected from the SWIFT system (Totensen and Bull, 2002; Biersteker et al., 2018). Just like comprehensive sanctions, sudden isolation of a country from international financial flows directly affects the quality of people’s life, but the concept has not been renamed. However, the effectiveness of such sanctions depends on the type of political regime against which they are directed. It is believed that authoritarian regimes are more resistant to comprehensive sanctions, while democratic regimes are more resilient against targeted sanctions (Major, 2012).

The second direction in which changes have taken place in the post-bipolar period shifted the focus from embargoes to financial and technological sanctions. The shift began during the Cold War, when Japan and Germany were the main states that helped third countries bypass the American trade embargo despite their own dependence on the U.S. economy, and intensified immensely after rapid globalization in the 1990s and 2000s (Hufbauer et al., 2007). At first, financial sanctions were used more and more often (to limit access to the American financial system and capital markets) (Hufbauer and Oegg, 2002), eventually followed by technological sanctions (sometimes in the form of financial restrictions but aimed at limiting access to technologies). While the former leave a window of opportunity for a gradual reorientation of capital markets, restrictions on the use of critical technologies almost certainly impede the development of a sanctioned country quite seriously and create strategic risks, as we can already see in the Russian oil and gas sector (Mitrova, Grushevenko and Malov, 2018). This indicates a gradual transition from sanctions as a disciplinary measure to sanctions as an instrument of deterrence.

The trend of recent years is the increasingly long-term nature of sanctions. This is borne out by the intensive codification of U.S. sanctions in the form of laws and persistent efforts by the legislative branch to snatch the sanctions agenda away from the executive branch just because it has been gaining more weight in U.S. domestic policy lately (Tama, 2019). The Congress previously passed sanctions acts against Libya, Iran (ILSA, ISA, etc.) and other countries, but their effectiveness was quite low. However, today the practice of sanctions legislation has changed. In 2017, the Congress legislatively codified presidential decrees that imposed sanctions on Russian companies and individuals, which makes them almost irrevocable. Such legislation is extremely inert, and even if the domestic political situation in the United States changes, one can hardly expect the anti-Russian or anti-Iranian restrictions adopted in the form of law to be lifted promptly. The best example is the Jackson-Vanik Amendment after the Soviet Union’s breakup (Timofev, 2017).

Finally, the expansion of sanctions toolkit relies on the use of pseudo-universal systems and international institutions solely for the benefit of Western countries: SWIFT, dollar settlements and correspondent banks, international development institutions, Visa and Master Card payment systems. Until the 2010s, they were positioned as an international public good and did work effectively for the globalization of the international financial system. Yet, when necessary, they were immediately used as a political tool, starting with the disconnection of Iran from the SWIFT system. On the other hand, this became a powerful catalyst for third countries to start their search for alternative financial institutions.

One of the most significant novelties in the field of sanctions concerned not so much sanctions per se as the system of oversight over their enforcement. The U.S. Department of the Treasury suggested monitoring compliance with sanctions by strengthening oversight mechanisms through financial systems and their participants. So, the responsibility to watch compliance with sanctions requirements was transferred from the Office for Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) to individual American banks. Under the threat of heavy penalties (up to $8 billion) or exclusion from the American financial system, the sanctions policy was actively outsourced to the private sector. This has been described in detail by one of its authors, Juan Zarate (Zarate, 2016). Supervision is carried out through the “financial compliance” of all persons interested in cooperating with the American financial system. New technologies capable of analyzing large amounts of data have undoubtedly played a big role in monitoring the enforcement of sanctions. In addition, informal criteria for the imposition of sanctions have been expanded: formal signs of circumvention of sanctions requirements, for example by means of bogus payments, are no longer necessary, as a company may be put on the sanctions list even on the basis of correspondence exposing its illegal activity.

From Action to Mode of Action

There is yet another change that has occurred in the sanctions agenda in recent years, which confirms that the nature of sanctions has gone from tactical to strategic: the deliberate strengthening of the unpredictability factor when “the mode of action” becomes more important than concrete actions themselves. While in the past the bargaining over sanctions boiled down to the terms of their lifting, now we can hear statements such as those by Kurt Volker: “We will impose new sanctions every one or two months” (Southfront.org, 2019), and see the Congress locked in fighting over “devilish bills” (Schroeder, 2018; Flatley and Weinstein, 2019; Mohsin and Wadhams, 2019).

Such practices fuel negative expectations among various stakeholders of international cooperation and result in the toxicity of jurisdiction as a whole rather than of specific individuals or entities. In other words, formal compliance with the policy of smart sanctions fulfils the goal of comprehensive sanctions. Such changes indicate a shift in the role of sanctions and their use for systemic deterrence.

UNILATERAL SANCTIONS IN A MULTIPOLAR WORLD: PROSPECTS

In general, there is a consensus on the issue of sanctions currently faced by both sanctioned countries and their partners who do not want to fall under secondary sanctions or reduce cooperation with the former. Moreover, the situation is complicated not only by the constantly growing number of specific sanctions and fines imposed for their violation, but also by increasing protectionist tendencies, which more and more often lead to open trade wars. Today one can identify a number of trends which will most likely determine the sanctions landscape in the medium term.

First, sanctions (aimed at achieving political objectives) are mixed with trade wars (aimed at obtaining economic benefits) due to increased competition among states in a less stable international environment (Timofeev, 2018a). This is not the first mixed “cocktail” in history: the embargo on Cuban sugar imports had a political nature, but American sugar producers welcomed it heartily. However such blending makes negotiation and deal-making much more difficult: this is true for both sanctions, because the conditions for lifting them are becoming increasingly unclear, and trade wars, because the most sensitive sanctions are justified by national security issues, but it is impossible to trade in national security.

This requires a sanctioned state to develop a proactive rather than reactive approach: a well-defined strategy of international cooperation with clear sanctions restrictions. Otherwise, it will be extremely difficult to reverse negative market expectations but, especially, to diversify partners and enter new markets.

As far as multilateral cooperation is concerned, it is likely to experience an ever-growing impact from sanctions. First of all, there are no global approaches and solutions to interstate disputes (SCO, RIC, BRICS could make some effort to fill this gap, but they have so far been trying to distance themselves from the issue of sanctions). Secondly, sanctions are becoming more prestigious and relatively cheap: the ability of a state to impose unilateral sanctions increases its status in the international arena. When Saudi Arabia imposes sanctions on Canada or Qatar, and a routine trade dispute between Uzbekistan and Ukraine is presented in the media as a risk of sanctions by Tashkent (Syundyukova, 2019), these events clearly show that sanctions are becoming a “new black color” in political fashion trends.

However, the international situation in five to ten years from now will be determined not only by the impact from sanctions, but also by the reaction to them, that is, by the countersanctions policy of many states. We will see more opportunities to make up for the negative effects of sanctions, in particular through integrated diversification of the international system:

- In the field of finance: capital markets will become more fragmented, new currency swaps will be used, and new payment instruments and systems will be created (Drezner, 2015). Nevertheless, one can hardly expect the U.S. dollar to be replaced by anything else as a means of saving rather than settlement.

- In the field of technology: new solutions will be introduced for fast and cheap localization of production processes, new technological hubs will be created to minimize negative effects from technological sanctions, and more intermediaries will support value-added chains. In fact, while thirty years ago only Western countries possessed critical technologies, access to which could be limited by the U.S. or the EU, today Asian countries can also offer a number of important technological solutions. Naturally, no parity in this area can be expected even in the medium term, but some progress has already been made (for example, in the field of artificial intelligence, renewable energy, materials science, genetics and selection, etc.).

- In the field of trade: new trade routes will be actively developed, including the “Belt and Road” and the North-South international transport corridor, and new substitutes will appear for traditional goods, even in the energy sector. These measures will have an indirect effect on the ability to resist financial sanctions, but as China, India, Russia, and Iran diversify their trading partners, all countries, not just the sanctioned ones, will get more incentives to develop non-dollar settlements and create alternative insurance companies.

These approaches will directly affect the fallout from sanctions. In the medium term, there will be fewer “avalanche” effects from sanctions, less confidence in the international system and higher costs of developing international cooperation (Riker, 2017), at least because it will be more expensive to maintain multiple channels of international cooperation than in a homogeneous international environment.

Due to diversification, sanctions are increasingly less likely to have truly devastating effects on sanctioned economies (Smeets, 2019) (if they could ever have them without military support at all (Pape, 1997)), but their deterrent effect on development will continue to be quite tangible. In other words, today states are actively mastering survival strategies, but the preparation of development strategies under sanctions requires a deeper transformation of the established economic and political processes.

The constant risk of sanctions will continue to reduce trust and discourage countries from launching joint long-term projects even after sanctions are lifted. The case of Iran clearly demonstrates that it is difficult for “traitors” to return to the previously sanctioned markets, because local businesses have already reoriented themselves to cooperation with other countries (Blockmans, Ehteshami and Bahgat, 2016). The decline of trust itself necessitates higher costs, including those associated with the hedging of foreign exchange risks (for example, using many foreign exchange swaps instead of one global currency) and financial support for exports. For example, in 1979, the U.S. and European countries accounted for 77% of Iranian exports, primarily oil, and for 65% of imports, while Asian countries accounted for 29% and 20%, respectively. In 2015, according to the International Trade Centre, Asia’s share in Iran’s exports exceeded 90%, and the total volume of Iranian imports from Asian countries amounted to 68%, which required the creation of a whole new infrastructure for trade with the new partners.

On the whole, under the influence of unilateral sanctions (but certainly not only them), the international system will become more dynamic, more mosaicked and more flexible.

For Russia and other sanctioned states, this has very clear implications for the development of international cooperation. On Russia’s traditional arms and energy export markets, which are vulnerable to sanctions, most solutions can be found only through high-level political transactions and sanctions risk hedging strategies for specific organizations (non-use of the U.S. dollar, involvement of special intermediaries, creative structuring of transactions, etc.).

As for the consequences for Russia, China, India, and other countries, especially Iran, U.S. sanctions increase risks for joint projects in such areas as energy, infrastructure, and international transport corridors. There is a need for flexible and dynamic solutions that can be developed taking into account the current nature of sanctions. Such solutions should be dynamic, autonomous from American jurisdiction as much as possible, and accessible to small and medium-sized players.

First, it is impossible to find a permanent solution to counter sanctions in 2019 and keep it working for years: the logic of U.S. sanctions policy implies constant adjustment, both instrumental and technological, every year or two, on average, with a view to making the global financial system as a whole more transparent. Western restrictions against Iran have confirmed that harsh sanctions are dynamic and accelerating, as is the policy of countering them (all stages of stepping up American sanctions against Iran were studied in detail and systematized by Kenneth Katzman, while the tightening of compliance practices was described in Juan Zarate’s book) (Katzman, 2019; Zarate, 2016). Otherwise, the negative effects of sanctions can wear out in a couple of years, and their continuation will be necessitated solely by the political situation, rather than by their objective effectiveness.

Second, the transition to national currencies in multilateral formats, such as Russia-Iran, India, China, opens the door to easier trade and currency balance adjustments. This is why it is essential to combine survival and development strategies when planning how to minimize the effects from sanctions.

Third, end-to-end solutions for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can be in demand in many countries. Strict requirements for risk management and sanctions compliance are too expensive for SMEs, and a certain “compliance package” sponsored by export support business associations can play a crucial role in driving their expectations. Otherwise, it will be easier for them to stay away from potentially toxic counterparties, or too costly to convince foreign partners that they are not “toxic.”

Finally, the diversification of value-added chains with a large number of beneficiaries can ensure greater sustainability of projects, and the example of Nord Stream-2 convincingly proves this. If the project were purely Russian, the chances of blocking it would be much higher.

This forecast is directly applicable to the Russian international strategy, more precisely to how it has been devised on the basis of the “anti-shock” therapy started in 2014.

RUSSIA AND SANCTIONS CHALLENGES: EFFECTS AND REACTIONS

It is generally believed that Russia’s reaction to the sanctions was a “shock” response, but five years on we can talk about concrete strategies to counter outside pressure.

First, the main goal was to hold out (Mau, 2015): to avoid a financial and foreign trade collapse (which would have cut off the supply of food, medicines, dual-use goods, components and other important commodities), and isolation in international institutions which Russia considers important for itself. In economic terms, this was first reduced to import substitution (2014-2015) in a narrow interpretation of this term, meaning full substitution for all stages of production chains, which proved ineffective and unattainable, and localization (since 2016), meaning attraction of foreign technologies and industrial solutions for the production of goods in Russia. These measures were supported and financed by the federal budget. The weakest spot in this policy was small and medium-sized enterprises operating outside the military-industrial and export (essentially strategic) sectors of the economy (Connolly, 2018). They have suffered from restrictions on capital markets but have not yet received sufficient support even though a number of SME development measures have been adopted, including the SME Development Corporation, the SME Bank, and regional development institutions.

The second goal of the Russian economy was to intensify the diversification started earlier, in 2008-2009. It was then that some members of the Russian elite began to acknowledge the potential of cooperation with Asian countries, primarily China, which was showing double-digit growth rates, and spoke about the need to modernize the economy to fit in new markets, and increase the added value of Russian-made goods, etc. (Karaganov, 2009). However, as Jeffrey Mankoff points out in his study of Russia’s Pivot to Asia, it was the sanctions that catalyzed this process and gave it an additional meaning for a wider circle of persons who make decisions concerning politics, business, and international military cooperation (Mankoff, 2015).

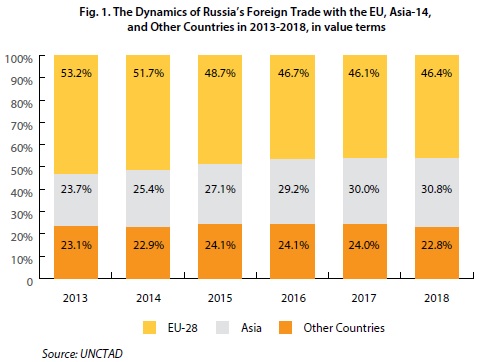

Today, there is no denying that the diversification of foreign economic relations is in progress: over the past five years Asia-14 (China, South Korea, Japan, India, and ASEAN countries) has taken 7% of Russian trade away from European countries (hereinafter all foreign trade statistics are based on UNCTAD data, unless stated otherwise). With Central and South Asian and Middle Eastern countries, which now account for more than 50% of Russia’s foreign trade turnover, this clearly shows that Greater Eurasia has turned from a political initiative announced in 2015 into a foreign trade model for Russia.

Just to compare, Iran needed fifteen years to restructure and redirect the first 10% of its trade turnover to Oriental countries: in 1979, Asian countries accounted for 29% of Iran’s exports and 20% of its imports, but by 1995 their share had grown to 44% and 28%, respectively, mainly at the expense of trade with the West.

Currently, the immediate economic challenges for Russia posed by sanctions boil down to two major problems: payment risks due to the significant role of the U.S. dollar in the Russian economy and capital market restrictions—borrowing openly on Western markets is completely out of the question, it is difficult and costly on non-Western markets working with the American financial system, and almost impossible under investment programs that were used routinely before.

On the plus side, more countries become aware of the need to diversify their payment instruments since they are also vulnerable to American sanctions, which means more potential partners for Russia. External incentives for third countries to fight their dependence on the U.S. dollar include not only anti-Russian, but also anti-Iranian sanctions, U.S. trade wars, tangible risks of sanctions against major Chinese players, and “secondary” sanctions against European businesses.

With regard to payment options, the main instruments of diversification are national currencies and currency swaps linked to them, and regional payment systems, the development of which was announced in the EAEU and BRICS. Barter and quasi-barter deals (which have proved quite effective in the case of Iran (Early, 2015)) may certainly be useful for circumventing sanctions, but the scale of such operations is limited to a certain extent and requires harmonization of the interests of exporters and importers. Otherwise barter deals will not be effective. And because of this specificity, they remain a solution for big business.

Despite full political support in Russia and partner countries for initiatives to reduce the role of the U.S. dollar, the level of operationalization in the financial market remains quite low. But since this process is underway not only in Russia but also in other countries, the first results can be expected already in the medium term (RBC, 2018).

Still, the systemic obstacle to complete rejection of the U.S. dollar is that it is very difficult to find a replacement for its savings function, as opposed to the payment one. The economic and psychological readiness to save, for example, the euro, not to mention the yuan or rupees, is still quite low, while gold, which the Russian Central Bank has been actively acquiring lately, could provide reliable insurance for a rainy day, but is of little help to active investment operations. As a result, Russia’s foreign debt is at its all-time low since January 1, 2008 ($483 billion as of July 1, 2019) and fully covered by the country’s gold and foreign exchange reserves ($518 billion as of July 1, 2019), which significantly increases resilience to external shocks, but complicates the implementation of programs designed to accelerate economic growth.

In addition to monetary nuances, sectoral sanctions against Russian banks and oil and gas companies have made it extremely difficult to attract external financing (Karaganov, 2018): reorientation to new markets creates a time gap that could be fatal for business, and the sociocultural conservatism of business elites makes things even worse.

At the same time, business inertia, which manifested itself most acutely in 2014-2016, remains a sensitive issue. This trend is particularly noticeable in the financial sector where the situation in the 2000s and the early 2010s led European banks and funds to offer lending and loan refinancing and restructuring services to Russian companies. The need for an urgent adjustment to persuade previously unknown partners in China and other Asian countries that cooperation could be attractive for them presented not only investment, but also sociocultural difficulties for Russian business elites. This process is far from over, largely due to limited human ties and low support for Oriental studies in Russia, which is not the case in countries that have similarly intensive business relationships with China or India.

Of all possible sources of investment, which do not contradict either the logic of sanctions risk hedging, or Russia’s real financial resources, or even the sociocultural traditions of doing business in Russia, the greatest potential is held by new development institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the BRICS New Development Bank. Russia is the third largest founder in the former, and holds a 20% share in the latter, but has very few projects supported in either of them.

Summarizing the above, Russia has two main strategies to counter sanctions: a survival strategy and a development strategy. The survival strategy has so far proved more effective. The country’s response in the field of security has been very systemic and addressed the biggest challenges:

- A national interbank settlement system has been created in case the country is disconnected from SWIFT

- Hedging practices have been developed to secure transactions outside of U.S. control by stimulating settlements in national currencies

- A national payment system has been created in case Visa and Master Card stop servicing Russian users

- Investments have been made in Russian production facilities as protection from trade sanctions (value-added chains redirected to Russia), in particular, in the field of agriculture and certain pharmaceuticals

- Low external debt remains a priority

- The Central Bank continues buying up “Doomsday” assets—gold.

The development strategy, not so successful so far, given current international tendencies, is based on three basic principles: flexibility, diversification and openness.

The first principle—flexibility—implies engagement in new institutions (AIIB and BRICS, which Russia is actively doing), integration into new value-added chains, including inside the EAEU, the priority of which was announced in presidential decree in May 2018, and measures to make the Russian economy more dynamic (which has not been achieved yet).

The main challenges here are related to sanctions indirectly. First, it is a business culture that is not sufficiently plastic in Russia; second, it is the balance between the state and business in the economy: in all examples of successful development under sanctions in major countries, such as China or Iran, priority was given to business as a more flexible player. But since access to external capital markets is limited, practically the only available source of financing today (directly or indirectly) is the state, which does not make it possible to task business with increasing the flexibility of the Russian economy.

The second task is diversification. The main challenges here are again internal: there is still no full determination to work with Asia in the long term. The main indicator of such determination will be the interest of business in carrying out specific educational programs necessary for successful work with Asian partners. However, Oriental studies curricula have not been revised and updated on a systemic basis either in higher or additional education institutions. Isolated programs are launched occasionally, but, in general, the level of knowledge about modern economic realities in Asia falls far behind not only that of American experts, but also of their Canadian, Australian, and European counterparts (Karaganov, 2018).

The third, somewhat paradoxical, principle of development strategy amid the global rise of protectionism is openness. This strategy requires active participation in free trade zones and acceleration of integration projects to “multiply ties,” rather than barricading oneself in a fortified fortress.

The main challenges here also stem from domestic factors rather than external sanctions: Russia’s conservative trade policy (until 2014 FTA agreements were rarely considered relevant, and a FTA with China, which has them with ASEAN countries, Korea, Australia, and even New Zealand, is still nearly taboo); backpedaling of Eurasian integration (which is going through a natural struggle of sovereignties); and a lack of interest among businesses in the development of new external relations (largely due to previously uncompetitive export support conditions for non-resource sectors—the Russian Export Center’s and Roseximbank’s activities are only getting underway, while such institutions in competing countries have been working successfully for decades).

So, despite modest results, the reason for optimism about the development strategy is that its main constraints are not so much external as internal. No matter how much the sanctions may be intensified, Russia still has extensive domestic resources for making its development policy more effective and productive.

In conclusion, as a systemic element of the international agenda, sanctions will stay there for decades because they reflect fundamental transformations in international spheres of influence. This factor should be taken into account when adopting state and interstate decisions, adjusting business strategies, and introducing and promoting new legal practices. Otherwise, sanctions designed to be a means of deterrence may prove quite effective as such.

References

Alnasrawi, A., 2001. Iraq: Economic Sanctions and Consequences, 1990–2000. Third World Quarterly, 22(2), pp. 205-218.

Bajak, F. and Liedtke, M., 2019. AP Explains: US Sanctions on Huawei Bite, But Who Gets Hurt? [online] Available at: https://www.citynews1130.com/2019/05/21/ap-explains-us-sanctions-on-huawei-bite-but-who-gets-hurt-2/ [Accessed 13 Aug. 2019].

Biersteker, T. et al., 2018. UN Targeted Sanctions Datasets (1991–2013). Journal of Peace Research, 55(3), pp. 404-412.

Blockmans, S., Ehteshami, A. and Bahgat, G., 2016. EU-Iran Relations after the Nuclear Deal. Brussels: CEPS.

Connolly, R., 2018. Russia’s Response to Sanctions. Cambridge University Press.

Conolly, R., 2018. Russia’s Response to Sanctions: How Western Sanctions Reshaped Political Economy in Russia. Russia in Global Affairs. Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/valday/Russias-Response-to-Sanctions-How-Western-Sanctions-Reshaped-Political-Economy-in-Russia-19865 [Accessed 13 August 2019].

Cordesman, A. and Hashim, A., 2018. Iraq: Sanctions and Beyond. New York: Routledge.

Dentons. 2019. US Sanctions Year-in-Review. [online] Available at: https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/alerts/2019/january/7/us-sanctions-year-in-review [Accessed 3 June 2019].

Drezner, D., 2011. Sanctions Sometimes Smart: Targeted Sanctions in Theory and Practice. International Studies Review, 13(1), pp. 96-108.

Drezner, D., 2015. Targeted Sanctions in a World of Global Finance. International Interactions, 41(4), pp. 755-764.

Drezner, D., 2018a. Economic sanctions are about more than imposing costs. [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2018/04/18/economic-sanctions-are-about-more-than-imposing-costs/?noredirect=on [Accessed 9 July 2019].

Drezner, D. 2018b. Why in the World Is Saudi Arabia Sanctioning Canada? [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2018/08/07/why-in-the-world-is-saudi-arabia-sanctioning-canada/ [Accessed 15 August 2019].

Early, B., 2015. Busted Sanctions. Stanford University Press.

Flatley, D. and Weinstein, A., 2019. House Democrats Restart Russia Sanctions Debate with Draft Bill. [online] Bloomberg, 15 May. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-15/house-democrats-restart-russia-sanctions-debate-with-draft-bill [Accessed 18 Aug. 2019].

Geranmayeh, E. and Rapnouil, M., 2019. Meeting the Challenge of Secondary Sanctions. [online] Available at: https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/meeting_the_challenge_of_secondary_sanctions [Accessed 15 August 2019].

Hufbauer, G. and Oegg, B, 2002. Capital-Market Access: New Frontier in the Sanctions Debate. [online] PIIE. Available at: https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/capital-market-access-new-frontier-sanctions-debate [Accessed 16 August 2019].

Hufbauer, G., Schott, J. and Oegg, B., 2019. Using Sanctions to Fight Terrorism. [online] PIIE. Available at: https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/using-sanctions-fight-terrorism [Accessed 17 July 2019].

Hufbauer, G., Schott, J., Elliott, K. and Oegg, B., 2007. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Ji-Hyang, J. and Lee, P., 2013. Do Sanctions Work? The Iran Sanctions Regime and Its Implications for Korea. 1st ed. Seoul: The Asian Institute for Policy Studies.

Karaganov, S., ed., 2009. Towards the Great Ocean or New Globalization of Russia. Valdai Club Report. Available at: http://vid-1.rian.ru/ig/valdai/Toward_great_ocean_eng.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2019].

Karaganov, S., ed., 2018. Towards the Great Ocean 6: People, History, Ideology, Education. Rediscovering the Identity. Valdai Club Report. Available at: http://valdaiclub.com/a/reports/report-toward-the-great-ocean-6/ [Accessed 13 August 2019].

Katzman, K., 2019. Iran Sanctions. Congressional Research Service. [online] Fas.org. Available at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/RS20871.pdf [Accessed 18 August 2019].

Koc, M., Jernigan, C. and Das, R., 2007. Food Security and Food Sovereignty in Iraq. Food, Culture & Society, 10(2), pp. 317-348.

Kozal, P. (2019). Is the Continues Use of Sanctions as Implemented against Iraq a Violation of International Human Rights? Denver Journal of International Law and Policy [online], 28(4), p. 383. Available at: https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-75375990/is-the-continued-use-of-sanctions-as-implemented-against [Accessed 13 August 2019].

Major, S., 2012. Timing Is Everything: Economic Sanctions, Regime Type, and Domestic Instability. International Interactions, 38(1), pp. 79-110.

Mankoff, J., 2015. Russia’s Asia Pivot: Confrontation or Cooperation? Asia Policy, 19(1), pp. 65-87.

Mau, V., 2015. Between Crises and Sanctions: Economic Policy of the Russian Federation. Post-Soviet Affairs, 32(4), pp. 350-377.

Mitrova, T., Grushevenko, E. and Malov, A., 2018. Perspectivy rossiskoy neftedobichy pod sanctsiami [Perspectives of Russian Oil Industry: Life under Sanction]. SKOLKOVO Energy Center. Available at: http://energy.skolkovo.ru/downloads/documents/SEneC/research04-ru.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2019].

Mohsin, S. and Wadhams, N., 2019. U.S. Readying Russia Sanctions for U.K. Poison Attack, Sources Say. [online] Bloomberg, 29 March. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-29/u-s-said-to-have-prepared-new-russia-sanctions-for-u-k-attack [Accessed 19 August 2019].

Newnham, R., 2015. Georgia on My Mind? Russian Sanctions and the End of the ‘Rose Revolution’. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 6(2), pp. 161-170.

Özertem, H., 2019. Turkey and Russia: A Fragile Friendship. Turkish Policy Quarterly, 15(4), pp. 121-134.

Pape, R., 1997. Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work. International Security, 22(2), p. 90.

RBC, 2018. Siluanov raskryl detali plana po dedollarizatsii rossiyskoy ekonomiki [Siluanov Discloses Detailed plan on Dedollarization of the Russian Economy]. Available at: https://www.rbc.ru/economics/04/10/2018/5bb5c95f9a7947709e4dac44 [Accessed 13 August 2019].

Reilly, J., 2012. China’s Unilateral Sanctions. The Washington Quarterly, 35(4), pp.121-133.

Riker, W. H., 2017. The Nature of Trust. In: Social Power and Political Influence. Routledge, pp. 63-81.

Schroeder, P. (2018). Rubio and Graham Call for Stronger Russian Sanctions if the Kremlin Commits Election Interference Again. [online]. Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/r-senators-push-sanctions-to-send-putin-message-on-election-interference-2018-7 [Accessed 18 August 2019].

Singhvi, A., Wong, E. and Lu, D., 2019. Defying U.S. Sanctions, China and Others Take Oil From 12 Iranian Tankers. [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/03/world/middleeast/us-iran-sanctions-ships.html [Accessed 12 August 2019].

Smeets, M., 2019. Can Economic Sanctions Be Effective? [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd201803_e.pdf [Accessed 18 August 2019].

Southfront, 2019. US to Impose New Sanctions on Russia Every 1-2 Months: Kurt Volker. Southfront, 18 October [online]. Available at: https://southfront.org/us-to-impose-new-sanctions-on-russia-every-1-2-months-kurt-volker/ [Accessed 19 August 2019].

Syundyukova, N., 2019. Uzbekistan Threatens Ukraine with Sanctions [online]. Available at: https://qazaqtimes.com/en/post/50500 [Accessed 18 August 2019].

Tama, J., 2019. Forcing the President’s Hand: How the US Congress Shapes Foreign Policy through Sanctions Legislation. Foreign Policy Analysis. [online] Available at: https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orz018/5539839 [Accessed 10 April 2019].

Timofeev, I., 2017. Smart Policy: How Should Russia Respond to US Sanctions? [online] Valdai Club. Available at: http://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/russia-respond-us-sanctions/ [Accessed 17 August 2019].

Timofeev, I., 2018a. Economic Sanctions as a Concept of Power Politics. MGIMO Review of International Relations, 2(59), pp. 26-42.

Timofeev, I., 2018b. Sankcii SShA protiv Irana: opyt primenenija i perspektivy razvitija [U.S. Sanctions against Iran: The Usage Experience and Perspective]. Polis: Political Studies, (4), pp. 56-71.

Tostensen, A. and Bull, B., 2002. Are Smart Sanctions Feasible? World Politics, 54(3), pp. 373-403.