Executive Summary

The main objective for the Shinzo Abe administration’s active engagement in supporting the involvement of Japanese companies in the development of the Russian Far East is to create favourable environment for resolution of the territorial issue and conclusion of a peace treaty with Russia. Japan– Russia cooperation in the Russian Far East is part of Abe’s 8-point cooperation plan with Moscow. In regard to economic cooperation, there are two categories to be discussed separately. One is the traditional area of cooperation that is energy such as oil and gas, initiated mainly by big companies. The other is shaped by new areas of businesses initiated mainly by small and medium-sized companies.

On energy cooperation, there were high expectations after the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011 that Japan–Russia cooperation could largely expand due to the rapid increase of Japan’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) import. Unfortunately, the results fell short of expectations due to a couple of reasons. Yet, in the coming decade there will be another chance of expanding cooperation in this area. Firstly, we will see the start of a new cycle of signing long-term LNG contracts by Japanese utilities companies in 2023 at the earliest. Secondly, it is highly likely that the overall Asia-Pacific region (APR), including China and ASEAN countries, will dramatically increase the volume of LNG import. Therefore, Japan–Russia energy cooperation potentially could expand not only in Japanese market but also in the whole APR in the near future.

On economic cooperation unrelated to energy, it is worth noting that we have seen several cases of Japanese small and medium-sized companies deciding to use the system of special economic zones in the Russian Far East to make direct investments in new areas of businesses such as agriculture, tourism, healthcare, etc. The volume has not been large so far, but it is to be counted as an achievement considering that this is a new trend in Japan–Russia economic cooperation. We need to make further efforts to accelerate and expand this positive trend.

The Main Objective of Abe’s Initiative

The Abe administration of Japan, in office since December 2012, has actively urged and supported the involvement of Japanese business in the development of the Russian Far East. The fact that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe himself attended the plenary session of the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) in Vladivostok for the third year in a row since 2016 clearly demonstrates his seriousness in this regard.

It is no secret that the main objective for his active engagement in this issue is to create favourable environment for resolution of the long-standing territorial issue and conclusion of a peace treaty with Russia. This approach has been based on the assumption that overcoming complex political issues like this requires the process of building full-scale confidence between Japan and Russia through deepening cooperative ties on all fronts including economy. One of priority areas for our economic cooperation must become the development of the Russian Far East, along with the joint economic activities on the disputed Kuril Islands. There has also been a special area of economic interaction in the Russian Far East that is energy cooperation, which should be analysed separately due to its different dynamics. The geographical definition of the Russian Far East in this context includes the Arctic region considering potential impacts of the development of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) on the Far East.

President Putin’s Hikiwake Remark in 2012

There could be several opinions on when the current process of active development of relations between the two countries began. It could be argued that the turning point was the then Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s remark of hikiwake (a Judo term meaning a ‘draw’) while talking about resolution of the territorial dispute during the Q&A session at the press-conference with foreign journalists, including Japanese Asahi newspaper, in March 2012, just two months before his return to presidency.

Traditionally the EU has been the most important economic partner for Russia. Its dependence on Europe has been very high with Europe being one of the main energy export markets for Russia and a vital source of . nance and technologies for Russian economic modernization. However, while the EU has entered a prolonged economic crisis after the Lehman Shock of September 2008 (the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., a global financial services firm), China recovered faster than other countries from the global crisis in 2010 with huge public investment. China’s maritime activities started intensifying in the East China Sea and the South China Sea around this period. In November 2011, the US administration of Barack Obama announced the ‘Pivot to Asia’ policy. With the rapid shift of the centre of gravity of world politics and economy, it was inevitable for Russia to start an active course of diversification of its economic partners from Europe to the APR. In this strategic context, the development of the Russian Far East as a gateway to the Asia-Paci. c has become one of the top strategic priorities for Vladimir Putin’s administration.

On the one hand, there is no doubt that the most important partner for Russia must be China that overtook Japan to become the world’s second largest economic power after the US in 2010. On the other hand, Russia wants to avoid excessive economic dependence on China as it could lead to its dependence in the political sphere as well. In these circumstances, the Putin administration has set the goal of diversifying its economic partners in the development of the Russian Far East as much as possible, including Japan, South Korea, etc. Japanese political elites took Vladimir Putin’s hikiwake remark seriously – as a kind of strategic signal from Russia.

The creation of the Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East and the hosting of the APEC summit meeting in Vladivostok in 2012 were the two major symbolic events for Russia’s Turn to the East policy initiated by President Putin. It was at the annual Presidential address to the Federal Assembly in December 2013 when he declared that ‘development of our Far East is a national priority for the 21st century’.

The 8-Point Cooperation Plan and Putin’s Visit to Japan

With the Abe administration in power since December 2012, high-level contacts between Japan and Russia have dramatically intensified. In April 2013, Abe visited Moscow with a Japanese business delegation of about 120 people and held a meeting with President Putin. In February 2014, Abe visited Russia again to attend the closing ceremony of the Sochi Winter Olympics and have another meeting with the Russian leader, which was the fifth Japan–Russia summit in less than one year. They reached an agreement on Putin’s visit to Japan in autumn 2014. However, with the Ukrainian crisis that followed, the relations between Russia and Western countries dramatically deteriorated, and Japan joined the US and EU sanctions on Russia as a G7 member. But Tokyo has managed to maintain the level of sanctions softer than the US and EU in order to minimize a negative impact on Abe’s initiative to strengthen Japan– Russia bilateral relations. Still, the planned President Putin’s visit to Japan was postponed to a more appropriate time.

The process of strengthening Japan–Russia relations resumed only after Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida’s visit to Moscow in September 2015. In May 2016, Abe proposed an 8-point plan of cooperation with Russia at the summit meeting in Sochi. This plan includes:

- extending healthy life expectancies;

- developing comfortable and clean cities easy to reside in;

- fundamentally expanding medium-sized and small companies exchange and cooperation;

- cooperating in the energy sphere;

- promoting industrial diversification and enhancing productivity in Russia;

- developing industries and export bases in the Far East;

- cooperating on cutting-edge technologies;

- substantially increasing people-to-people interaction.

Later, in September 2016, Abe attended the EEF in Vladivostok for the first time and held another meeting with Putin. At the same time, he appointed Hiroshige Seko, Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) to the post of the head of the Ministry for Economic Cooperation with Russia, which is in charge of materializing the 8-point cooperation plan. In December 2016, President Putin finally visited Tokyo. On this occasion, under the 8-point cooperation plan, 80 documents were signed between the two governments’ authorities and among businesses. The two governments also agreed to start discussions on joint economic activities on the four disputed islands.

Lost Opportunities after the Fukushima Accident

The area in which Russia started the policy of diversification to extend to APR before 2012, was energy. The Sakhalin-1 and the Sakhalin-2 projects, both of which have Japanese shareholders, started exporting oil in 1999 and 2005, respectively. And against the backdrop of growing oil prices, Transneft, the Russian state-owned oil transport monopoly, started the construction of the Eastern Siberian–Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline from Tayshet of Irkutsk Oblast to Skovorodino of Amur Oblast in 2006. The ESPO pipeline was launched in 2009. LNG exports from the Sakhalin-2 project began in 2009, remaining the first and only LNG plant in Russia until recently. It is fair to say that 2009 was the year when Russia’s diversification of oil and gas markets to the Asia-Paci.c greatly accelerated. The ESPO oil pipeline extended from Skovorodino to Kozmino of Primorsky Krai in 2012.

The Great East Japan Earthquake and the following Fukushima nuclear accident in March 2011 caused a dramatic increase of Japan’s demand for natural gas. This initially raised expectations that Japan could expand cooperation in the . eld of natural gas with Russia.

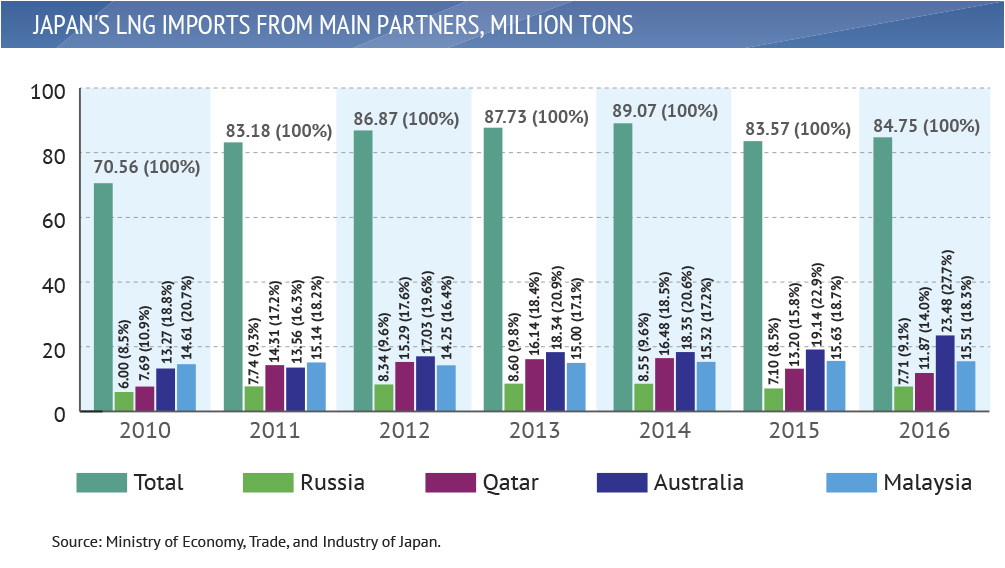

Surrounded by sea on all four sides, Japan imports all of its natural gas in the form of LNG. In 2010, its total volume reached 70.56 million tons, and in 2014 it increased by 26% to 89.07 million tons. As was mentioned above, the Sakhalin-2 LNG plant, operated by Sakhalin Energy, started exporting LNG in 2009, remaining the sole LNG exporter in Russia. Its shareholders include Gazprom (50% plus one share), Royal Dutch Shell (27.5% minus one share), as well as Japan’s Mitsui (12.5%) and Mitsubishi (10%). The volume of Russia’s LNG export to Japan was 6 million tons in 2010, increasing to 8.6 million tons in 2013. But after hitting the peak in 2013, Russia’s LNG export to Japan has decreased to around less than 8 million tons in the past two years. Notably, Russia’s share remains much smaller than this of Qatar and Australia. Qatar’s LNG export to Japan increased from 7.69 in 2010 to 16.48 million tons in 2014. Australia also grew its LNG export to Japan from 13.27 in 2010 to 23.48 million tons in 2016.

The main reason for this was that there was a limited room for production increase in the Skakhalin-2 LNG plant, the only plant in Russia at that time, with 9.6 million tons per year of the design capacity of its production trains. Therefore, for further increase of LNG export to Japan, Russia needed to build new plants or expand the production capacity of the Sakhalin-2 LNG facility.

Even before March 2011, Gazprom had a plan to build a new LNG plant in Vladivostok. Gazprom also intended to expand the production capacity of Sakhalin-2 LNG facility by means of adding a third train. Moreover, debates on partial liberalization of Gazprom’s gas export monopoly started within Russia’s energy industry in autumn 2012. Novatek, Russia’s biggest independent gas company, and Rusneft, Russia’s state-owned oil company, took their initiatives for the debates, demanding a licence for LNG exports, and obtained the LNG export right in November 2013. The former planned to build a new LNG facility with design production capacity of 16.5 million tons per year on Yamal peninsula in the Arctic region, while the latter planned to build a new LNG plant in the Far East.

As mentioned above, Japanese companies participated in the Sakhalin-2 LNG project as shareholders. The Japanese government and several Japanese companies were involved in Gazprom’s Vladivostok LNG project from its initial phase. According to soma data, Rosneft’s new LNG project in the Far East looked set to have Japanese investors if it had been actually launched. Novatek initially approached Japanese companies for their participation in the Yamal LNG project. Since then five years have passed, and so far Novatek’s Yamal LNG facility has reached the Final Investment Decision (FID) and started operation. At least two factors may be the reason for such an outcome:

- Unfavourable market conditions for LNG suppliers after the sharp drop in oil prices in 2014–2015.

- Lack of reliable sources of gas supply for Gazprom.

This should be explained more in detail. Gazprom had three gas fields in East Siberia and the Far East that could be counted as reliable sources for gas supply in Gazprom’s LNG projects – Chayanda field in Yakutia, Kovykyta field in Irkutsk, and the Yuzhno-Kirinskoye field of the Sakhalin-3. However, in May 2014, Gazprom singed a 30-year natural gas supply contract with China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). Under this contract, Gazprom agreed to supply 38 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas per year from the Chayanda and Kovykta fields. Moreover, the Yuzhno-Kirinskoye field of the Sakhalin-3 has been under US sectoral sanctions since August 2015.

Nevertheless, regardless of uncertainties over the global LNG market, Novatek’s Yamal LNG project reached the FID in December 2013 and started its operation in 2017. There may be at least two important factors underlying the successful implementation of this project. Firstly, Russian government has provided Novatek with full support, including infrastructure development and tax exemption. Secondly, Novatek succeeded in getting the participation of Chinese investors, including CNPC (20%) and Silk Road Fund (9.9%), in addition to France’s Total (20%). Japanese companies decided not to join the Yamal LNG project as shareholders. Yet, whatever technological dif.culties this project could have faced, the joint venture of JGC and CHIYODA, Japanese two major engineering companies, played the role of an engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contractor for the first ever in history LNG project in the Arctic region and started LNG production at the first train of this plant in November 2017.

In this regard, in December 2016, Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) signed a credit line facility with Yamal LNG for €200m for exporting Japanese-made plant facilities. Besides, Japanese companies have also been actively involved in the LNG transportation work from the Arctic to the APR. In July 2014, Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL), a Japanese major shipping company, together with China Shipping Company declared to join the transportation work for Yamal LNG project by signing contracts with Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Co. to build three ice-class LNG carriers. In March 2018, their first vessel, Vladimir Rusanov, started its operation at the port of Sabetta, Yamal Peninsula.

Investments by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

Beyond the energy sphere, there are other areas of Japan–Russia cooperation worth looking at. In line with the 8-point cooperation plan proposed by the Japanese government as part of efforts to create favourable environment for the resolution of the long-standing territorial issue and the conclusion of a peace treaty with Russia, Tokyo has actively supported the expansion of economic cooperation between the two countries.Yet, needless to say, whatever support the government provides, Japanese companies never make investments in the Russian Far East without any business feasibility. From this perspective, it is fair to say that a series of the Russian government’s measures, including the creation of Territories of Advanced Social and Economic Development (TORs) and the Free port of Vladivostok (FPV), have begun to produce certain positive effects.

As of June 30, 2018, as much as six Japan-related entities have been registered as residents of TORs. Among them is Japan–Russia joint venture (JV) JGC Evergreen initiated by the JGC Corporation, Japanese engineering company, that has launched a greenhouse project in Khabarovsk, providing local people with fresh cucumbers and tomatoes. Sayuri, initiated by the Japanese Hokkaido Corporation has started another greenhouse project in Yakutsk. Japan–Russia JV Honoka Sakhalin joined by Marushin Iwadera, one of Japanese biggest hot-spring spa operators, has begun working on the .rst Japanese-style hot-springs spa resort in Sakhalin. Japanese Arai Shoji plans to start two ventures with Russian partners: Terminator project on car recycling and Prometheus – on electric car’s spare production. Mazda Sollers, joint venture of the Japanese Mazda Motor and the Russian Sollers, plans to start production of car engines in Vladivostok in 2018, with Mazda Sollers having operated the car assembly Vladivostok plant since 2012.

Apart from that, two Japan-related entities have been registered as residents of the FPV. Among them are stevedoring company Slavic Forest Terminal created by Iida Group Holdings, which plans to build factories for advanced timber processing and saw timber production in Primorsky Krai, and JGC Hokuto Healthcare Service, established by JGC and Hokuto Social Medical Corporation, which has opened a rehabilitation centre in Vladivostok in May 2018.

As is obvious from these examples, areas of Japanese direct investments in Russia have begun to diversify from traditional energy and auto-related big businesses into small and medium-sized new businesses such as agriculture, tourism, healthcare, etc. Yet, this development has just begun. Japan and Russia need to make further efforts in order to speed up and expand this progress. In April 2018, Teruo Asada, Chair of the Japan–Russia Business Cooperation Committee of the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren), made the following remark at the Japan–Russia Forum in Moscow.

Recently, we have observed some positive trends in our trade and investment relations. But this is not enough considering economic potential of both countries. We, Keidanren, understand that the development of the Far East region will be the litmus test to determine the future of the overall Japan–Russia economic relations, but so far only a small number of Japanese companies have utilized the system of special economic zones. We have not seen serious progress in some big projects as we had expected.

Asada made three proposals to Russian government: (1) infrastructure improvement, (2) extension of tax exemption period, and (3) aftercare services for investments. Concerning the latter, JBIC, the Far East Investment and Export Agency (FEIA), and the Far East Development Fund (FEDF) of.cially announced the formation of the Joint Japanese Project Promotion Vehicle in the Far East LLC (Far East JPPV) in February 2018 at the Sochi Economic Forum. It aims to provide advisory services to Japanese companies, which make investment in TORs and the FPV in the Far East. It is very timely to create the Far East JPPV at the moment when Japanese investments from small and medium-sized companies have begun to extend to the Far East. Moreover, as part of the 8-point cooperation plan, in September 2017, JBIC IG, a subsidiary of JBIC, together with the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) launched the Russia–Japan Investment Fund (RJIF), a joint investment framework in which each party has committed $500m. As of June 30, 2018, RJIF has made three investment decisions, including two energy and infrastructure related companies and a healthcare related company.

With regard to joint economic activities on the disputed Kuril Islands, which are also considered as part of Japan–Russia bilateral cooperation in the Russian Far East, Japanese and Russian governments have already identified the following five candidate projects: (1) propagation and aquaculture of marine products facility, (2) greenhouse vegetable cultivation project, (3) tour development based on the islands’ features, (4) introduction of wind-power generation, and (5) garbage volume reduction measures. Government-to-government dialogues on the legal framework for the implementation of these projects continue. The two foreign ministries play the central role in this process.

Conclusion. New Opportunities in Energy Cooperation

Returning to the subject of Japan–Russia energy cooperation in the Far East, the following should be considered. According to the report The Latest Development in Natural Gas & LNG, conducted by Japan Oil, Gas, and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) under METI, although it could change depending on the number of operating nuclear power plants, Japanese utilities companies might sign new long-term contracts of purchasing LNG – with its demand in mind – from 2023 at the earliest and 2024 at the latest. Besides, it is highly likely that the demand of LNG in the overall APR, including China and ASEAN countries, will dramatically increase in the coming decades. Against this backdrop, in recent years we have observed new LNG projects in Russia reactivated.

The Sakhalin Energy, majority-owned by Gazprom, has been working on the third train expansion plan of the Sakhalin-2 LNG plant. Rosneft has also been considering the possibility to construct a new LNG facility in the Far East. In June 2018, Alexey Miller, Chairman of the Gazprom Management Committee, mentioned the possibility to reactivate the Vladivostok LNG project, which Gazprom had postponed indefinitely in 2015. The possibility of Japan–Russia gas pipeline construction project, which will connect Sakhalin and Hokkaido, has been under exploration for a long time. Novatek has also worked on a new LNG project in Gydan Peninsula in the Arctic (the Arctic-2 LNG facility). In May 2018, France’s Total, the earliest partner of the Yamal LNG project, agreed to purchase 10% of the Arctic-2 LNG project by obtaining a 10% stake. According to press releases, Novatek has also discussed potential cooperation on this project with Japanese Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Marubeni, and the Korean KOGAS. In this regard, there is a new development trend in the field of LNG transportation. In November 2017, Novatek, MOL, and Marubeni signed a Memorandum of Understanding on a joint feasibility study aimed at establishing an LNG transhipment and marketing complex in Kamchatka Krai. This project will create off-shore infrastructure to tranship LNG cargoes from ice-breaking LNG ships to standard LNG vessels. The project will ensure flexible LNG supply to the APR.

However, there are many new LNG projects aimed at marketing products in the APR not only in Russia but also in USA and Australia. Needless to say, the above-mentioned Russian LNG projects will face severe competition with its American and Australian counterparts. The key for successful realization of projects is, first and foremost, a timely implementation as well as offers of competitive prices. Whatever the case, one thing is clear. The future of Japan– Russia energy cooperation has a big potential to expand not only in Japanese market but also in the whole APR.

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.