With sufficient political will, it would be possible to secure an extension of the New START treaty even after the US presidential inauguration on January 20, 2021. Russia and the US have a wealth of experience of interaction on nuclear-related topics, including the conclusion and extension of bilateral agreements in that area. They also possess adequate diplomatic and technological instruments that, with sufficient political will in both capitals, can help them to achieve a shared goal under time-pressing circumstances.

Introduction

The Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, known as the New START treaty,[1],[2] is the last Russian-US arms control agreement still in force. It is currently set to expire on February 5, 2021. Under Article XIV of the Treaty, it can be extended for a period of up to five years. On December 5, 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin proposed to the United States to agree on a New START extension “as soon as possible” and “without any preconditions”.[3],[4] The Russian head of state’s initiative was formalized in a diplomatic note prepared by the Russian Foreign Ministry and delivered to the US Department of State on December 20, 2019. The note contained a proposal to extend the Treaty “as is” and “without any preconditions”, as well as to conduct a bilateral meeting of experts to discuss all the issues related to a New START extension.[5] As far as the authors of this paper are aware, as of May 31, 2020, there has been no official response from the US Department of State.[6]

In their comments, Russian Foreign Ministry officials increasingly emphasize that a New START extension would have to be ratified by Russian parliament – the Federal Assembly – and that the process could take months.[7],[8] In February 2020, Russia proposed to the United States to hold a meeting of Russian Foreign Ministry and US Department of State legal experts in order to exchange information about the national procedures that would be required for a New START extension – but Washington avoided such a meeting.[9] In response to diplomatic signals from Moscow that the time has come to begin a substantive discussion on the extension procedures, US officials say there is no rush. On March 9, 2020, during a briefing on the New START, a senior State Department official said that “[…] our understanding is that legally speaking the extension of the treaty provision […] is already baked into the text of the treaty, which has already been subject to advice and consent and ratification. So from our perspective it would take […] nothing more than an exchange of diplomatic notes. I will leave it to the Russians to characterize what their process might or might not involve […]”.[10]

This paper offers a detailed review of the Russian national procedures that would be required for a New START extension. Also, with only eight months remaining until the Treaty’s expiration, a continued absence of a political decision on extension in Washington, and the US presidential election looming on the horizon later this year, this paper estimates the minimum time frame that would be required to complete all the bilateral and national procedures needed for an extension of the last remaining Russian-US arms control treaty. Other factors (domestic and foreign policy, military, economic, technological, and other considerations) that affect the outlook for the Treaty’s extension deserve separate in-depth analyses, and are deliberately excluded from the scope of this research.

New START and Russia’s legal system

Before discussing the procedure of extending the New START in accordance with Russian law, let us first examine the process of the Treaty’s ratification in Russia.

The procedure of conclusion, implementation, and termination of international agreements is stipulated by Federal Law № 101-FZ of July 15, 1995 “On International Treaties of the Russian Federation” (hereinafter referred to as Law №101). Under Law №101, the New START treaty was subject to ratification by the Russian legislature because it met three ratification criteria.[11] First, under Paragraph 1.a, Article 15, a ratification is required for all international agreements “if their implementation requires changes to the existing federal laws or the adoption of new laws, or if they establish rules that are different from those currently established by law”. In this particular case, the issue at stake was granting the inspectors and aircrew members various privileges and immunities – which essentially establishes a special legal regime for them that is different from the regular regime stipulated by Russian law.

Second, Paragraph 1.d (1.г), Article 15 of Law №101 stipulates that ratification is required for treaties “dealing with issues that pertain to the defense of the Russian Federation, disarmament or arms control, and international peace and security”.

Third, under Paragraph 2, Article 15, “international treaties require ratification if the parties have established such a requirement in the text of the treaty”. Article XIV of the New START stipulates that “This Treaty […] shall be subject to ratification in accordance with the constitutional procedures of each Party”.

Based on Paragraph d (г), Article 84 of the Russian Constitution, and in accordance with Federal Law №101, the Russian president submitted the New START treaty for ratification to the Duma (lower chamber of the Russian Federal Assembly) on May 28, 2010. In accordance with Paragraph 4, Article 16 of Law №101, the letter to the Chairman of the Duma contained 7 attachments: 1) draft federal law “On the Ratification of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms”; 2) a presidential order appointing official presidential representatives for the ratification process; 3) a certified copy of the official text of the Treaty; 4) a letter of approval of the draft federal law on ratification from the Russian Government; 5) an explanatory note attached to the draft law; 6) a conclusion on the financial and economic feasibility of the draft law; and 7) a list of federal acts that would have to be terminated, suspended, amended or newly adopted in connection with the adoption of the proposed federal law on ratification. The entire package of documents submitted to the Duma consisted of 315 pages.[12]

The Russian Government’s approval of the draft federal law on the ratification of the New START treaty was required under Article 104 of the Russian Constitution because the treaty is categorized as “[…] necessitating expenses covered from the federal budget”.[13]

The Russian president appointed Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and then-Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov his official representatives for the New START ratification process at the Russian Federal Assembly.

On June 1, 2010, the Council of the Duma put the Committee on International Affairs in charge of reviewing the draft federal law on the New START ratification; the Defense Committee was asked to contribute to the process. The International Affairs Committee was instructed to provide its assessment, analysis, and recommendations on the draft submitted by the president, and to prepare the draft for the Duma hearings. The committee then initiated consultations with the relevant government ministries and agencies, as well as experts and members of the academia. On June 26, 2010, the Duma committees for international affairs, defense, and security held a joint private session to discuss the military-political, defense, and technological implications of the treaty; the session was attended by Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defense officials. On July 8, 2010, the draft federal law “On the Ratification of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms” was presented at the meeting of the International Affairs Committee; the meeting was attended by officials from the Foreign Ministry and the General Staff of the Armed Forces. The committee issued a recommendation for the Duma to approve the draft federal law. At the same sitting, it was proposed to put the hearing on the draft bill on the agenda of the Duma’s autumn 2010 session.

Further work on the draft bill was then put on hold in order to “synchronize” the ratification process with the United States in view of the New START treaty’s significance for national security and strategic stability, and also given the historic record of other nonproliferation and arms control agreements (such as the CWC[14] and the CTBT[15]) passing through the US legislature.

The New START ratification resolution passed by the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (SCFR) on September 16, 2010 contained several declarations and understandings on a number of issues (such as missile defense, strategic-range non-nuclear-weapon systems, etc.) that were substantial for Russia in terms of their strategic stability implications.[16] After studying the SCFR resolution, the Duma International Affairs Committee decided in early November 2010 to review once again the draft of Russia’s own New START ratification bill in order to include several amendments and to issue a statement on behalf of the Duma explaining its stance on the matter.

The full US Senate passed the New START resolution of advice and consent on December 22, 2010.[17] The following day, the Duma put the ratification bill on its own agenda. There were three separate readings of that bill: on December 24, 2010; on January 14, 2011; and on January 25, 2011. After approval by the Duma, the bill was submitted for the vetting of the Federation Council (upper chamber of parliament) on January 25–26, and on January 28, Federal Law №1-FZ “On the Ratification of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms” (Federal Law №1) was signed by then-President Dmitry Medvedev.[18]

To summarize, the New START ratification process took 8 months from the submission of the ratification bill to the Russian Duma to its signature by the Russian president. The period from the signing of New START by the two presidents to its ratification by Russian parliament was 9,5 months.

Procedure of the New START extension in Russia

Under Paragraph 2, Article XIV of the New START treaty, “if either Party raises the issue of extension of this Treaty, the Parties shall jointly consider the matter. If the Parties decide to extend this Treaty, it will be extended for a period of no more than five years […]”.[19]

In their statements, Russian and US officials have mentioned the possibility of extending the New START for less than the maximum period of five years[20] allowed by the treaty itself.[21] In May 2020, it was reported that one of the options being seriously considered by the Trump administration was an extension of the Treaty for a period of less than five years.[22]

An extension of an international treaty can be accomplished by the parties’ consent using such means as exchanging diplomatic notes or letters, signing a joint protocol, or concluding an agreement on an extension of the treaty. For Russia, the preferred method is to sign a single document – an extension protocol. The practice of extending a treaty by means of exchanging diplomatic notes is also fairly common: a case in point is the Agreement Between the United States of America and the Russian Federation Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes.[23] However, it is uncommon for Russia to use an exchange of diplomatic notes for those international agreements that require ratification.[24]

Article 1 of Law №101 “On International Treaties of the Russian Federation” reads as follows: “The present Federal Law shall apply to the international treaties of the Russian Federation […] regardless of their type and name (treaty, agreement, convention, protocol, exchange of letters or notes, and other types and names of international treaties)”. Therefore, from the Russian legal perspective, concluding a New START extension agreement is equivalent to concluding a separate international treaty. In this context, regardless of the chosen form of extension, the extension agreement (for instance, a joint protocol or an exchange of diplomatic notes) would be subject to ratification based on two of the three criteria that required the New START itself to go through the ratification process. First, the New START extension agreement would pertain to issues of defense, disarmament, and arms control (Paragraph 1.d (1.г), Article 15 of Law №101). Second, the extension agreement would implement rules that are different from the ones that already exist under Russian law (Paragraph 1.a, Article 15). These “different rules”, in particular, include granting inspectors and inspection plane aircrews’ various privileges and immunities. Under the Protocol to the New START treaty (Part Five, Section II), they are granted the same privileges as diplomatic agents, as stipulated in Article 29 of the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. These privileges and immunities include inviolability of personnel, immunity of the inspectors’ and aircrews’ papers and correspondence, and immunity of the inspection planes that transport the inspection teams to and from the entry/exit ports. Additionally, inspectors and aircrew members have the right to import into the Russian Federation items for their personal use without paying any customs duties, taxes or charges.[25]

Ratification of the New START extension agreement is a procedure required by Russian law rather than by the Treaty itself. In the United States, there is no requirement to ratify such an agreement.[26] When the New START treaty was originally ratified by Russia in 2011, the Russian legislature gave its consent for Russia to be bound by the terms of the Treaty for a fixed period of 10 years. The right to extend that period also belongs to the legislature.

The Russian president would have had the right to extend the New START by his own executive decision only if such a right had been granted to him during ratification and incorporated into the text of the law on the New START ratification (Federal Law №1). The Russian president’s powers with regard to the implementation of the Treaty are formulated in Article 3.2.1 of Federal Law №1. The respective section reads as follows: “the President of the Russian Federation […] determines the main directions of Russian international policy in the areas of strategic offensive weapons and missile defense for the purpose of strengthening strategic stability and national security, […] conducts consultations and negotiations with the leaders of foreign states for the purpose of strengthening strategic stability and Russian national security”.[27] But there is no indication in the text of Federal Law №1 that the president has the power to extend the New START treaty. As a result, incorporating the New START extension agreement into the Russian legal system requires the approval of that document by the legislature by means of ratification.

There are precedents in Russian legal practice of the legislature delegating some of its powers on specific issues to the president. A case in point is the suspension of Russia’s participation in the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE). According to Article 2 of Federal Law №276-FZ “On the Suspension of Russian Federation Participation in the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe” of November 29, 2007, “the decision to resume participation in the Treaty shall be made by the President of the Russian Federation”.[28]

A relevant example of a nuclear risk reduction agreement awaiting an extension that will have to be ratified by the Russian legislature is the Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Notification of Ballistic Missile and Space Vehicle Launches.[29] The original 10-year term of that Treaty expires on December 16, 2020. Under Paragraph 2, Article 13 of the Agreement, “[…] the Parties shall hold consultations to discuss an extension of this Agreement not later than one year before the expiration of its 10-year term […]”. Moscow and Beijing have already exchanged diplomatic notes to confirm their interest in extending the treaty. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, Russian and Chinese officials has already started the process of negotiating an extension protocol. Like the New START, an extension of this agreement will also have to be ratified by Russian parliament, and Beijing has already been notified of this requirement.[30]

There is also an example of a Russian-US nuclear-related agreement that has been extended following a ratification of the extension by the Russian legislature. The Agreement between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on the Safe and Secure Transportation, Storage and Destruction of Weapons and the Prevention of Weapons Proliferation was signed by Presidents Boris Yeltsin and George H.W. Bush on June 17, 1992. It laid down the legal framework of the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program, also known as the Nunn-Lugar Program. That program contributed to the implementation of arms control commitments, including those undertaken under the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), at the time of Russia’s economic transition. The agreement entered into force for a seven-year period on the day of its signature, and was subsequently extended twice for additional seven-year periods. Extensions were accomplished by means of signing extension protocols on June 15–16, 1999, and on June 16, 2006, respectively. Both of these protocols were subject to ratification because, like the New START treaty, they also met the criteria under Paragraphs 1.a and 1.d, Article 15, of Law №101. More specifically, they had defense, disarmament, and arms control implications, while also establishing a new regime (different from the normal Russian legal regime) on such issues as customs duties, taxes and charges exemptions; liability for damage; and privileges and immunities.[31],[32]

Five steps towards a New START extension and the time they would take to implement

Since there is only about eight months left before the expiration of the New START’s original 10-year term, the matter of its extension becomes especially urgent. Now that time is of the essence, the authors would like to analyze how long it would take to complete all the extension-related procedures (including those required by Russian law).

In the history of Russian-US relations, there have already been precedents of time factor playing the decisive role in the entry into force of bilateral nuclear-related agreements. These include, for example, the Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Russian Federation for Cooperation in the Field of Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy (the so-called 123 Agreement). The document was signed on May 6, 2008, and entered into force on January 11, 2011. Due to the nature of the US legal process, the agreement had to be submitted for Congressional review twice. The second submission happened under the Obama administration, and a successful outcome of Congressional review was only accomplished thanks to the longest “lame-duck” sitting of the outgoing Congress in almost three decades.[33]

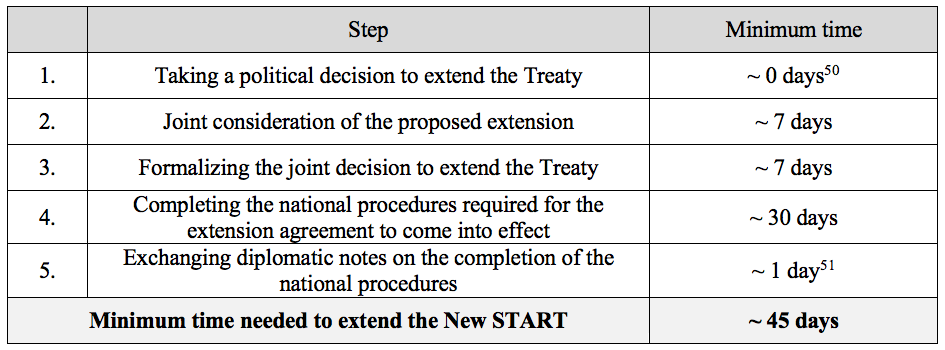

Since there are many different factors that can affect the pace of the extension procedure at its various stages, including factors that are hard to predict, let us estimate the shortest possible amount of time that would be required to formalize a legally-binding New START extension. Such a procedure would include five key steps: 1) taking a political decision to extend the Treaty; 2) completing a bilateral “joint consideration” of the proposed extension; 3) formalizing the joint decision to extend the Treaty (for example, by signing an extension protocol or exchanging diplomatic notes); 4) completing the national procedures required for the extension agreement to come into effect; and 5) exchanging diplomatic notes on the completion of the national procedures.

Step 1. A political decision to extend the Treaty

The first step both parties would have to take is to confirm their consent to extend the New START Treaty; that decision must be taken by the two heads of state. President Putin announced Russia’s willingness to extend the New START without any preconditions in December 2019. The ball is now in Washington’s court, but there have been mixed signals from the US capital, including statements that the interagency process to decide the future of the Treaty is still ongoing. There have also been signals that the US would like to change the fundamental nature of the Treaty by bringing in a new state party (China) and by extending the scope of the Treaty (through including new types of Russian strategic weapons systems).[34]

For the purposes of this paper, the authors assume that the White House will eventually agree to extend the New START in its original form – otherwise there is no point to any further deliberations. Therefore, the countdown of the period for the extension procedure would begin once the US president announces Washington’s willingness to extend the last remaining Russian-US arms control agreement.

Step 2. Joint consideration of the proposed extension

The next step would be to jointly consider a New START extension and, if needed, to negotiate an extension agreement. In this context, “extension agreement” refers to any specific extension instrument (a protocol, an exchange of diplomatic notes, etc.) chosen by the two parties. For Russia, launching such negotiations would not require any additional decisions by the president or the government. Under Article 9.6 of Law №101 “On International Treaties of the Russian Federation”, “the federal executive bodies […] have the right to hold consultations with the relevant bodies of foreign states […] for the purpose of preparing drafts of international treaties […] and to submit […] proposals on concluding such treaties to the President of the Russian Federation or the Government of the Russian Federation”. As previously noted, the Russian Foreign Ministry has already formalized its proposal to conduct negotiations on extending the New START in a diplomatic note delivered to the US Department of State on December 20, 2019.

Once the joint effort begins, the two parties will have to decide on: a) the format of the document on extending the New START treaty; b) a clause on the extension agreement’s entry into force, in view of the need for the parties to complete their respective national procedures; and c) the length of the extension (no longer than 5 years). If the parties agree on a single document (such as a protocol) as their preferred instrument of extending the Treaty, the draft should be produced in Russian and in English. It is hard to imagine the bilateral review of the issue of extending the Treaty – completed using an in-person process or remotely, given the ongoing pandemic and travel restrictions – taking less than a week.

Based on the considerations outlined in the previous section, it seems that signing an extension protocol would be the preferred method of extending the New START. The authors of this paper therefore propose a draft Protocol on the extension of the New START as a possible starting point for further discussions involving government officials, diplomats, members of the research community, and the academia (see Annex 1).

Step 3. Formalizing the joint decision to extend the Treaty

As far as the Russian side of the process is concerned, formalizing the joint decision to extend the New START (for example, by signing an extension protocol or exchanging diplomatic notes) would require the consent of the Russian president. Under Article 9 of Law №101, the Russian Foreign Ministry, independently or in cooperation with other relevant government agencies, must submit its proposal on concluding the agreement to the president. Under Article 9.5 of that Law, “a proposal on concluding an international treaty must contain a draft of that treaty or its main clauses, an explanation of the rationale for concluding the treaty, a conclusion on the treaty’s compliance with national legislation, and an estimate of the potential financial and economic implications of concluding the treaty”. The proposal must also be approved by the relevant federal ministries and agencies.

Based on these documents, the president’s office must then draft a presidential order on signing (concluding) the New START extension agreement. The order will formally approve the Foreign Ministry’s proposal and instruct it to sign the agreement on behalf of the Russian Federation. The president may also choose to sign the agreement personally. In such an event, the text of the order must contain a clause about the document being signed at the presidential level.

Since several agencies will have to be involved in reviewing the draft of a New START extension agreement, it is safe to assume that even under the most optimistic scenario, this will take a week at the very least.

Given the importance of the New START for the nuclear nonproliferation regime and international security, should the parties choose a single document as the format of extension agreement, the preferred option to proceed would be to conduct an official signing ceremony involving the two presidents and hosted by one of the European cities; alternatively, the ceremony may involve the Russian foreign minister and the US secretary of state. The New START treaty itself was signed in Prague, and the bilateral meetings on strategic stability issues held in 2017–2020 were hosted by Geneva, Helsinki, and Vienna.

The time frame for the extension agreement signing ceremony may be affected by the busy schedules of the two presidents (or the foreign minister and the secretary of state). If the agreement is to be signed by the foreign minister and the secretary of state, and if the two parties manage to complete all the necessary procedures before mid-January 2021, then the 10th NPT Review Conference, postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic and provisionally scheduled for January 2021, could be used as a venue for the signing ceremony. This would also serve as a good opportunity for the world’s two largest nuclear powers to reaffirm their commitment to Article VI of the NPT, and could also have a positive effect on the course of the NPT Review Conference itself.

Another possible format would be to hold two separate signing ceremonies in Moscow and Washington. For example, the Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Russian Federation Concerning the Management and Disposition of Plutonium Designated as No Longer Required for Defense Purposes and Related Cooperation (the Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement) was signed in Moscow by Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov on August 29, 2000, and in Washington, DC by Vice President Al Gore on September 1, 2000. Another example is the Protocol on the extension of the June 17, 1992 Agreement between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on the Safe and Secure Transportation, Storage and Destruction of Weapons and the Prevention of Weapons Proliferation. The Protocol was signed on June 15, 1999 in the Russian capital by US Ambassador to the Russian Federation James Collins, and the next day in Washington, DC by Russian Ambassador to the United States Yuri Ushakov. Since time is of the essence, such a format can be useful as it would enable the parties to save several days. In fact, it may turn out to be the only possible format if the pandemic-related restrictions aren’t lifted by the time the extension agreement is ready for signature.

Step 4. Completing the national procedures required for the extension agreement to come into effect

As already explained, the extension agreement would have to be approved by the Russian legislature (by means of passing a federal law to that effect) before it can enter into force.

On the basis of Article 16.2 of Law №101, proposals on the submission of international treaties to parliament for ratification are initially presented to the president by the Foreign Ministry (independently or in cooperation with other federal executive bodies). Before the draft law on the New START ratification is submitted to the Duma, it would have to be approved by the Government because the implementation of the treaty after its extension would require funds from the federal budget.[35] After the approval letter is signed by the prime minister, it should be submitted to the president.

The extension agreement ratification process would be identical to the process used for the original New START treaty. It would begin with the submission of the draft law on ratification to the Duma by the president. The submission should include the same package of documents that was presented with the New START when it was submitted for ratification. Overall, the entire procedure would include the following stages: Foreign Ministry > Government > President > State Duma > Federation Council > President.

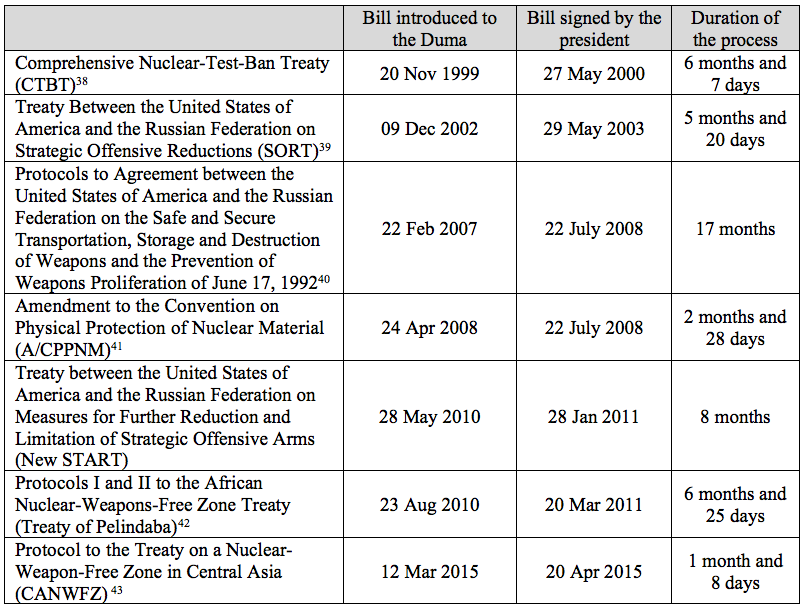

The table below cites several multilateral and bilateral nonproliferation and arms control agreements signed by Russia,[36] and the time it took the Russian legislature to ratify those agreements.

Table 1. Ratification of international nuclear-related agreements by Russian parliament

Let us recall that the ratification of the New START treaty took 8 months from the date of the bill’s submission to the Duma. The average length of time it took to ratify the treaties listed in the table above is approximately 7 months.[43] The speediest ratification (of the Protocol to the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia) took 1 month and 8 days. There is also a precedent of an even faster ratification of an international treaty – the Kyoto Protocol, which took only 28 days to ratify – but this should be considered a rare exception.[44],[45] It should also be remembered that the last 40 days of the New START treaty’s original 10-year term will overlap with the New Year and Christmas holidays in Russia, which are tentatively scheduled to last from January 1 to January 10, 2021.

The ratification of the New START extension agreement could be speeded up should the Duma decide to reduce the number of ratification bill readings from three to one.[46] The ratification procedures for the Protocol to the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia and for the Kyoto Protocol were completed in one reading. A single reading was not the only factor that enabled such a speedy ratification, but it certainly helped a lot. Another way to win time would be to accelerate the interagency vetting process of the draft bill before its submission to the Federal Assembly.[47]

To summarize, since the extension of the New START treaty is a presidential initiative, the Federal Assembly can be expected to consider the bill a top priority and pass it within the shortest technically possible time frame – but that time frame, as we have just demonstrated, is physically unlikely to be shorter than about a month.

Step 5. Exchanging diplomatic notes on the completion of the national procedures

The final step is exchanging diplomatic notes on the completion of the national procedures required for the extension of the Treaty to come into effect. Under Article 18 of Law №101, “in accordance with a federal law on the ratification of international treaty, the President of the Russian Federation signs the instrument of ratification bearing the presidential seal and the signature of the Minister of Foreign Affairs”. Unless the parties specifically agree otherwise, the procedure of exchanging the instruments of ratification (diplomatic notes) is carried out by the Russian Foreign Ministry or on behalf of the ministry by the Russian diplomatic mission to the respective foreign state or international organization.

Let us recall that Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton exchanged the instruments of ratification of the New START treaty on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference on February 5, 2011.[48] If the parties are unable to use the upcoming 10th NPT Review Conference as a symbolic venue for signing the extension agreement, that conference could still be used as an occasion to exchange the diplomatic notes on the agreement’s entry into force. It is also worth mentioning that Vladimir Putin and George W. Bush exchanged the instruments of ratification of the SORT Treaty during a meeting in Strelna (St. Petersburg) on March 1, 2003.

Table 2. Estimated minimum time frame required to extend the New START

It is therefore safe to assume that even under the very best-case scenario, the entire process of concluding an agreement on the extension of the New START treaty and completing all the national procedures required for the extension to enter into force will take at least 45 days from the moment of the US President announcing his political decision to initiate an extension. That minimum time frame will likely increase by another 10 days should the process overlap with the Russian holiday period on January 1–10, 2021.

Possible scenarios in view of the upcoming U.S. presidential election

Let us now adjust these projections to reflect the political realities in the United States, where, as May 31, 2020, the current administration has yet to take a political decision on whether to extend the New START treaty. The next US presidential election will take place on November 3, 2020; the incumbent President Donald Trump will contend for the office with the Democratic candidate (presumably Joe Biden).

In this context, there are three possible scenarios with regard to the future of the New START.

Scenario 1: The United States refuses to extend the Treaty, allowing it to expire on February 5, 2021. The demise of the last remaining Russian-US instrument of mutual predictability and transparency in the area of strategic weapons would multiply the risks of the two parties sliding towards an uncontrolled arms race. The arms control regime as the world has known it over the past several decades would cease to exist.

Scenario 2: The current administration agrees to the New START extension in its original form, and this happens before the US presidential election. Should the US decision to extend the treaty be announced before November 2020, the two parties would have enough time to negotiate an extension agreement, sign it (if needed), and complete the national procedures required for its entry into force by February 5, 2021. However, a move to extend the treaty that was conceived by the previous administration (in which the likely Democratic nominee Joe Biden served as vice-president) could be politically toxic to Donald Trump if it comes in the final weeks of his campaign in October 2020. Scenario 2 is therefore based on the assumption that if the Trump administration decides to extend the New START, it will probably try to do so before the end of September 2020. Let us recall at this point that the 75th session of the UN General Assembly is scheduled to open on September 15, 2020.

Scenario 3: Washington decides to extend the New START treaty after the presidential election. If Donald Trump is re-elected, such a decision, should it be taken no later than December 10, would probably leave Russia and the United States enough time to negotiate an extension and complete all the required national procedures despite the Christmas and New Year holidays in both countries. If the US president takes the decision to extend the treaty after December 10 (but before the last week of January 2021), the extension would still be possible, but it would require a clause on the provisional application of the extension agreement.

If the Democratic candidate wins the election, the new administration will be able to act on the New START extension only after the inauguration – in other words, not before January 20, 2021. Therefore, there will be only 16 days left until the expiration of the New START treaty.[51] The only possible way of preserving the Treaty in such circumstances would be to hold urgent consultations on the issue of extension and conclude an extension agreement as soon as possible, making sure to include a provisional application clause.

Russia is one of the states where the executive branch has the power to authorize (without the approval of the legislature) a provisional application of those international treaties that require parliamentary ratification (and the passage of a ratification bill) to enter into force – provided that the treaty itself has a provisional application clause. Article 23 of Law №101 reads that “an international treaty or a part thereof may be implemented by Russia on a provisional basis if such a possibility is included in the treaty or if this has been agreed upon by the parties to the treaty”.

A provisionally implemented New START extension agreement would have the same legal power as any international agreement that has entered into force because it would fall under the scope of the pacta sunt servanda principle of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (“Every treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith“, Article XXVI). But provisional implementation is no real substitute for a proper entry into force. Law №101 requires that a provisionally implemented agreement must be submitted for ratification within six months of its signature. According to some legal experts, failure to meet that requirement engenders a conflict between national and international law.[52] In the context of the New START extension, such a conflict could, among other things, create a gray area with regard to the immunities and privileges of US inspectors and aircrews in Russian territory.

In the event of the Democratic candidate winning the election, it may become necessary to reinvigorate the Russian-US Track 2 expert dialogue in the period from November 2020 to January 2021. Such dialogue could potentially facilitate the New START extension process as Moscow and Washington will have very little time left to complete the preparations following the arrival of the new US administration. Dialogue between the US and Russian expert and academic communities would also help to identify the modalities so that by the time the 46th US president is sworn in on January 20, 2021, there is at least a mutual understanding of how to proceed in order to preserve the New START treaty for another period of up to five years.

Conclusion

Any further delay with deciding the future of the New START treaty now that there is only about 8 months left until it expires is a huge and completely unjustifiable risk. The COVID-19 pandemic not only imposes restrictions on international cooperation (including security-related efforts), but also poses new challenges. But the pandemic is no excuse for letting the last remaining Russian-US arms control agreement expire. Modern communication technologies make it possible to discuss the issue remotely in a safe and secure way. The time has come for the current US administration to complete the interagency process on a New START extension. Such issues as involving other countries or extending the scope of the Treaty to cover new strategic weapons systems will take time. They can indeed be put on the agenda – but only after the New START treaty has been extended, giving the parties up to five more years to hold consultations and negotiations on the matter. For the moment, the next step would be to launch, as soon as possible, a regular Russian-US dialogue on the entire range of issues related to the treaty’s extension. As this paper has demonstrated, the completion of all the required procedures, including the national procedures stipulated by Russian law, would take 45–55 days at the very least.

But with sufficient political will, it would be possible to secure an extension of the New START treaty even after the US presidential inauguration on January 20, 2021. Russia and the US have a wealth of experience of interaction on nuclear-related topics, including the conclusion and extension of bilateral agreements in that area. They also possess adequate diplomatic and technological instruments that, with sufficient political will in both capitals, can help them to achieve a shared goal under time-pressing circumstances.

The New START treaty plays a very special role in the system of Russian-US bilateral relations. It serves the national interests of both states. It is also a crucial element of the entire international security architecture. The treaty imposes mutual restrictions on both countries’ strategic arsenals; very importantly, it also gives the two parties valuable information about the current state of each other’s strategic capability.[53] Over the past 9 years since the treaty’s entry into force, the parties have conducted 300 inspections and exchanged over 20,000 notifications on their strategic forces.[54] Further, the New START has established a multi-layered system of Russian-US interaction – a system that is valuable in and of itself amid the severely reduced number of “communication channels” that still remain open between the two nuclear superpowers. The demise of the last standing Russian-US arms control agreement, coming in the wake of the US decision to pull out of the ABM, INF, and now the Open Skies treaties, would affect the two countries’ bilateral relations as well as global security. It would make the world more vulnerable and less predictable by potentially triggering an uncontrolled arms race at a time when every single country in the world, Russia and the United States included, should focus instead on rebuilding their economies from the devastation COVID-19. Last but not least, the expiration of the New START treaty would further complicate the situation with the NPT, which is already going through a very rough patch.

Annex 1

PROTOCOL

between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on the Extension of the Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms

The United States of America and the Russian Federation, hereinafter referred to as the Parties,

In accordance with Article XIV of the Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms signed in Prague on April 8, 2010, hereinafter referred to as the Treaty,

Have agreed as follows:

Article 1

The Treaty shall be extended by five years from February 5, 2021 unless it is superseded earlier by a subsequent agreement on the reduction and limitation of strategic offensive arms.

Article 2

This Protocol [shall be applied provisionally from the date of signature and*] shall enter into force on the date of receipt of the last written notifications that the Parties have completed the internal governmental procedures necessary for its entry into force.

Done at [place][date], in two originals, each in the English and Russian languages, both texts being equally authentic.

[Signatures]

* – This provision will have to be included in the text of the Protocol if the parties conclude that they do not have sufficient time to complete the internal procedures necessary for the Protocol’s entry into force by February 5, 2021.

______________

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ildar Akhtamzyan, Amb. Sergey Batsanov, Amb. Grigory Berdennikov, Gen. Evgeny Buzhinsky, Mr. Vladislav Chernavskikh, Gen. Viktor Esin, Mr. Oleg Khodyrev, Amb. Sergey Kislyak, Mr. Dmitry Konukhov, Hon. Konstantin Kosachev, Amb. Mikhail Lysenko, Amb. Yury Nazarkin, Acad. Sergey Rogov, Hon. Leonid Slutsky, Dr. Nikolai Sokov, Hon. Inga Yumasheva, representatives of the Department for Nonproliferation and Arms Control (DNKV) and the Legal Department of the Russian Foreign Ministry, staff members of the Committee on International Affairs of the State Duma and the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, as well as experts who wish to remain anonymous, for their help in preparing this paper and for their reviews of the draft. At the same time, the authors take sole responsibility for the views presented in this article.

[1] The Treaty was signed in Prague, Czech Republic, on April 8, 2010 by Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and US President Barack Obama. It entered into force on February 5, 2011 after Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton exchanged instruments of ratification in Munich, Germany.

[2] In publications by Russian governmental agencies, think-tanks, and media outlets, the Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms is referred to in English as the New START, or as START III. For the sake of consistency, the treaty will be referred to as the New START in this paper.

[3] Meeting with Defence Ministry Leadership and Heads of Defence Industry Enterprises, December 5, 2019. Russian President’s Official Website. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/62250 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[4] Russian President Vladimir Putin first officially announced Russia’s readiness to extend the New START treaty during a Russian-US summit in Helsinki, Finland, on July 16, 2018. Prior to early December 2019, Russian officials made the extension conditional on resolving several contentious issues, including the conversion of strategic delivery systems by the United States. According to Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Moscow had “questions about the US declaration on the conversion of a large number of SLBM launchers and heavy bombers […] for non-nuclear use. The Treaty permits this, but the conversion should be accomplished in such a way as to allow the other party to confirm with a 100-percent certainty that these converted SLBM launchers and bombers cannot be reverted to nuclear capability”. See: Lavrov Announces Russia’s Readiness to Discuss a New START Extension (in Russian). 2019, May 13. https://russian.rt.com/world/news/630612-lavrov-ssha-snv (Retrieved on April, 30, 2020).

[5] Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov’s Interview with the Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn journal, April 17, 2020. https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/4103408?p_p_id=101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw&_101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw_languageId=en_GB (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[6] Some Russian experts point out that the continuing US evasion from joint consideration of a New START extension goes in contradiction of their obligations under Article XIV of the Treaty: “If either Party raises the issue of extension of this Treaty, the Parties shall jointly consider the matter”. Telephone interview with former Russian Ambassador, Representative to the Conference on Disarmament Sergey Batsanov, May 18, 2020.

[7] Sergey Lavrov: Russia Will Respond to Aggressive US Rhetoric (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 2019, December 27. https://ria.ru/20191227/1562899110.html (Retrieved on April 30, 2020); Russian Foreign Ministry: It Will Take Months to Extend the New START Treaty (in Russian). Rossiyskaya Gazeta. 2019, December 11. https://rg.ru/2019/12/11/riabkov-rossii-ponadobiatsia-mesiacy-na-prodlenie-snv-3.html (Retrieved on April 30, 2020); Russia’s View on Nuclear Arms Control: An Interview with Ambassador Anatoly Antonov. Arms Control Today. 2020, April. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-04/interviews/russias-view-nuclear-arms-control-interview-ambassador-anatoly-antonov (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[8] It should be noted that there is no consensus in the Russian expert community on whether a New START extension agreement would be subject to ratification by the Federal Assembly. Some think-tank representatives believe there is no need for a ratification as the extension provision is part of the text of the Treaty, and that the consent to extend the Treaty was received from the Russian legislature at the time of the original New START ratification.

[9] Russian Foreign Ministry: The US Has Declined to Participate in a Meeting of Legal Experts on the Issue of the New START Extension (in Russian). Regnum. 2020, February 27. https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2869447.html (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[10] Briefing with Senior State Department Official on the New START, March 9, 2020. https://www.state.gov/briefing-with-senior-state-department-official-on-the-new-start/ (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[11] See Explanatory Note to the draft federal law “On the Ratification of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms”. This note is part of a package of documents submitted by the President of the Russian Federation to the Chairman of the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation during the submission of the New START for ratification. The full text of the document is available in Russian at the Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/382931-5 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[12] Letter from Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to the Speaker of the Russian State Duma Boris Gryzlov, Pr-№1553 of May 28, 2010 (in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/382931-5 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[13] Constitution of the Russian Federation, Article 104. http://www.constitution.ru/en/10003000-06.htm (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[14] The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) was opened for signature on January 13, 1993. During the CWC ratification process in the United States, a number of senators argued that the Convention could pose a threat to national security and pushed for granting the US president the right to block challenge inspections in accordance with Article IX of the CWC – which would directly contravene the Convention itself. Such a provision was eventually added as part of the CWC Implementation Act adopted by the Senate in 1998. In addition to that, the Implementation Act and the ratification resolution (adopted by the Senate in 1997) included a ban on removing chemical samples taken in US territory in the course of the implementation of the Convention for detailed analysis at laboratories overseas, which also contravenes the CWC. Details available at: The US Chemical Weapons Convention Implementation Act of 1998. https://www.cwc.gov/cwc_authority_ratification_text.html (Retrieved on April 30, 2020); Jonathan B. Tucker, The Chemical Weapons Convention: Has It Enhanced U.S. Security?. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2001-04/features/chemical-weapons-convention-enhanced-us-security (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[15] The Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) was opened for signature on September 24, 1996. In the US Senate, the Treaty did not get the votes needed for ratification on October 13, 1999. The treaty has yet to be ratified by the United States, which is one of the states whose ratification is required for the Treaty to enter into force. According to US media reports, there are growing discussions in Washington on ‘unsigning’ the CTBT and resuming nuclear tests. See: Hudson John, Sonne Paul. Trump Administration Discussed Conducting First U.S. Nuclear Test in Decades. Washington Post. 2020, May 23. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/trump-administration-discussed-conducting-first-us-nuclear-test-in-decades/2020/05/22/a805c904-9c5b-11ea-b60c-3be060a4f8e1_story.html (Retrieved on May 30, 2020).

[16] U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Treaty with Russia on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (The New START treaty), Executive Report, 111th Cong., 2nd sess., October 1, 2010, Exec. Rept 111-6. https://www.congress.gov/111/crpt/erpt6/CRPT-111erpt6.pdf (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[17] For an in-depth analysis of the US Senate ratification resolution on the New START, and of the Russian Duma’s position on the issue, see: Anatoly Antonov. Arms Control: History, Current State, Prospects (in Russian). M: Russian Political Encyclopedia (ROSSPEN); PIR Center, 2012. P. 53–63. http://mil.ru/files/morf/A_Antonov__monografia.pdf (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[18] Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Draft Law №382931-5 “On the Ratification of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms” (in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/382931-5 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[19] Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, Article XIV. The US Department of State Official Website. https://2009-2017.state.gov/t/avc/newstart/c44126.htm (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[20] Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov Briefing on the Termination of the INF Treaty, August 5, 2019. The MFA Russia Official Website. https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/3750835?p_p_id=101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw&_101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw_languageId=en_GB (Retrieved on April 30, 2020); Testimony of Christopher Ford, Assistant Secretary of State for International Security and Nonproliferation, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing on U.S. Policy Toward Russia, December 3, 2019. https://www.c-span.org/video/?466936-1/undersecretary-david-hale-testifies-us-policy-russia (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[21] The authors of this paper believe that given the complexity and the time-consuming nature of the negotiating process to conclude a new arms control agreement to succeed the New START,

the preferred option is to extend the New START for the permitted maximum period of five years.

[22] Bender Bryan. White House Weighs Shorter Extension of Nuclear Arms Pact with Russia. Politico. 2020, May 20. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/20/white-house-russia-nuclear-271729 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[23] Agreement Between the United States of America and the Russian Federation Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes, June 17, 1992. https://aerospace.org/sites/default/files/policy_archives/Cooperation%20in%20Peaceful%20Use%20of%20Space%20-%20Russia%20Jun92.pdf (Retrieved on April 30, 2020); Amending and Extending the Agreement of June 17, 1992, Effected by Exchange of Notes at Moscow, December 3 and 26, 2007 and January 25, 2008. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/07-1227.1-Russian-Federation-Space-Peacef-Notes-Amends.pdf (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[24] Recommendations on the Procedural Matters for Preparing Materials Related to Concluding or Terminating International Treaties of the Russian Federation (in Russian). The MFA Russia Official Website, April 1, 2009. https://www.mid.ru/foreign_policy/international_contracts/international_contracts/-/asset_publisher/kxW4m3muIEqP/content/id/787306 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[25] Protocol to the Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms. https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/140047.pdf (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[26] Antonov Anatoly, Gottemoeller Rose. Keeping Peace in the Nuclear Age. Foreign Affairs. 2020, April 29. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-04-29/keeping-peace-nuclear-age (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[27] Federal Law №1-FZ of January 28, 2011 “On the Ratification of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms”, Article 3 (in Russian). Rossiyskaya Gazeta. 2011, February 1. https://rg.ru/2011/02/01/snv-dok.html (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[28] Federal Law №276-FZ of November 29, 2007, “On the Suspension of Russian Federation Participation in the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe” (in Russian). http://pravo.gov.ru/proxy/ips/?doc_itself=&nd=102118448&page=1&rdk=0&i#I0 (Retrieved on

April 30, 2020).

[29] The agreement was signed in Beijing on October 13, 2009; it was ratified by Russia on November 3, 2010, and entered into force on December 16, 2010. See: Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Notification of Ballistic Missile and Space Vehicle Launches of December 16, 2010 (in Russian). http://docs.cntd.ru/document/902196991 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[30] An interesting precedent of an extension of an international nuclear-related treaty (which deserves

a separate study or even a series of studies from the standpoint of international and national legal aspects) is the indefinite extension of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which was adopted by the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference by consensus and not subjected to further ratification by the NPT States Parties’ national legislatures.

[31] The protocols were ratified simultaneously by means of adoption of Federal Law №128-FZ

of July 22, 2008 “On the Ratification of Protocols to the Agreement between the Russian Federation and the United States of America on the Safe and Secure Transportation, Storage and Destruction of Weapons and the Prevention of Weapons Proliferation of June 17, 1992”; prior to that date, they were implemented on a provisional basis in accordance with the protocols’ respective provisions.

See (in Russian): https://rg.ru/2008/07/30/orugie-dok.html (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[32] Detailed information on the ratification of the Protocols to the Agreement between the Russian Federation and the United States of America on the Safe and Secure Transportation, Storage and Destruction of Weapons and the Prevention of Weapons Proliferation of June 17, 1992 is provided

(in Russian) in the Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/398020-4 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[33] That agreement, which is commonly referred to as the 123 Agreement, did not require ratification either in Russia or in the US. However, according to US law, the procedure of Congressional review was as follows: the document was to be submitted to Congress for 90 days in continuous session, and, unless Congress passed a joint resolution opposing the document during that period, the Agreement would come into effect after an exchange of diplomatic notes between the states parties. The Agreement was submitted to US lawmakers on May 13, 2008, but at that point there were only

77 session days left before the last sitting of the 110th Congress. Therefore, it had to be submitted for Congressional review once again, which happened under the Obama administration. However, the 111th Congress also had fewer than 90 continuous session days left at the time of submission, and there was a risk that a third submission of the Russian-US 123 Agreement would be required. However, the session of the 111th Congress after the election of the 112th Congress (the so-called “lame duck” session) lasted longer than ever in the preceding 28 years (the previous time the House of Representatives had the “lame duck” session lasting 13 or more days was in 1982), which provided enough time for successful outcome of Congressional review. For more details, see: Khlopkov Anton. US-Russian 123 Agreement Enters into Force: What Next? 2011, January 11. http://ceness-russia.org/data/doc/US-Russian-123-Agreement-Enters-Into-Force-What-Next.pdf (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[34] Gertz Bill. Exclusive: Envoy Says China Is Key to New Arms Deal with Russia. 2020, May 7. Washington Times. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2020/may/7/marshall-billingslea-says-new-start-fate-hangs-chi/ (Retrieved on April 30, 2020); Testimony of Christopher Ford, Assistant Secretary of State for International Security and Nonproliferation, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing on U.S. Policy Toward Russia, December 3, 2019. https://www.c-span.org/video/?466936-1/undersecretary-david-hale-testifies-us-policy-russia (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[35] Constitution of the Russian Federation, Article 104. http://www.constitution.ru/en/10003000-06.htm (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[36] For the purposes of this article, the authors cite a selection of nuclear-related agreements signed by the Russian Federation. The table does not include any agreements signed during the Soviet period because the Soviet legislation was different.

[37] Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Draft Law №99109728-2 “On the Ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty” (in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/99109728-2 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[38] Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Draft Law №272852-3 “On the Ratification of the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Strategic Offensive Reductions” (in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/272852-3 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[39] Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Draft Law №398020-4 “On the Ratification of the Protocols to the Agreement between the Russian Federation and the United States of America on the Safe and Secure Transportation, Storage and Destruction of Weapons and the Prevention of Weapons Proliferation of June 17, 1992” (in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/398020-4 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[40] Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Draft Law №50396-5

“On the Adoption of Amendment to the Convention on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material”

(in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/50396-5 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[41] Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Draft Law №421977-5

“On the Ratification of Protocols I and II to the African Nuclear-Weapons Free-Zone Treaty”

(in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/421977-5 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[42] Legislation Support System of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Draft Law №742436-6

“On the Ratification of the Protocol to the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia”

(in Russian). https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/742436-6 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[43] To be exact, the average length of ratification of the nuclear-related agreements listed in the table

is 6 months and 25 days.

[44] The ratification of the Kyoto Protocol is considered one of the speediest ratifications by the Russian legislature. The law “On the Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change” took only 28 days to approve (from October 7 to November 4, 2004).

[45] There have been examples of a ratification of international treaties by the Russian legislature taking several years. For instance, the ratification of the Open Skies Treaty in the Federal Assembly took more than 6,5 years (the draft bill was submitted to the State Duma on September 13, 1994, and adopted on May 26, 2001). See: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/94700197-2 (Retrieved on April 30, 2020). However, since an extension of the New START has been initiated by the Russian president himself, there are solid grounds to believe that in this case, such a scenario is highly unrealistic.

[46] In accordance with the Resolution of the State Duma of the Russian Federation of January 22, 1998 No. 2134-II “On Regulations of the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation”: “as a result of the draft bill discussion the State Duma can accept or approve the draft bill in the first reading and continue working on it with consideration of proposed commentaries and amendments, or to adopt or approve the law […] or to reject the bill. […] If the bill is adopted in the first reading […], or the bill is approved in the first reading, the Chair may put to vote the proposal of the Committee in charge to adopt or approve the law skipping the second and third readings […].” For more details

(in Russian): http://duma.gov.ru/duma/about/regulations/chapter-13/ (Retrieved on April 30, 2020). The adoption of bills on ratification of international treaties is carried out in three readings when more detailed discussions, preparation of federal law accompanying statements, etc. are needed. Regarding the New START treaty, the Information and Analysis Bulletin of the 5th State Duma Spring session of 2011 emphasizes that “the ratification procedure was conducted in three readings, so that […] the draft bill was amended with conditions which, in the opinion of MPs, were necessary for […] the START Treaty implementation”. For more details (in Russian): http://iam.duma.gov.ru/node/1/4896# (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[47] It is worth mentioning that under Russian Government Resolution №260 of June 1, 2004

“On Regulations of the Government of the Russian Federation and Regulations on the Executive Office of the Government of the Russian Federation”, the vetting of draft federal laws and presidential executive orders by the respective agencies should take up to 10 days since their receipt. That period can be shortened should the document be designated as ‘urgent’. See: http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_47927/ba269782742c5d460477b346c08f821af8de8647/ (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[48] It would be highly symbolic to exchange the documents on the completion of the New START extension national procedures at the 2021 Munich Security Conference, but to the best of the authors’ knowledge, the conference is provisionally scheduled for February 19–21, 2021 – meaning that it will kick off after the formal expiration of the New START on February 5, 2021.

[49] As a starting point for their calculations, the authors have chosen the moment of the hoped-for US presidential announcement of the political decision to extend the New START treaty in its original form.

[50] This estimate is based on a very optimistic scenario that would be hard (if not impossible) to accomplish; it would require the instruments of ratification to be exchanged the very next day after the Russian ratification bill is signed by President Putin.

[51] Joe Biden, the likely Democratic nominee for the upcoming election, has already announced his intention to pursue an extension of the New START. See: Biden, Joseph R., Jr. Why America Must Lead Again. Foreign Affairs. 2020, March/April. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again (Retrieved on May 30, 2020).

[52] Osminin Boris. Practice of Provisional Application of International Treaties in Different Countries (in Russian). Mezhdunarodnoye Pravo. 2013, No. 12. P. 119. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/vremennoe-primenenie-mezhdunarodnyh-dogovorov-praktika-gosudarstv (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[53] Esin Victor. Critical Factors for the New START Extension. Yadernyy Klub (Nuclear Club).

2019, No. 1–2 (37–38). P. 12–14. Available in English at https://vcdnp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/19-11-07-Gen.-Esins-Discussion-Paper-ENG.pdf (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).

[54] Statement by the Foreign Ministry Concerning the 10th Anniversary of the Signing of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the United States of America on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms. https://www.mid.ru/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/4096810?p_p_id=101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw&_101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw_languageId=en_GB (Retrieved on April 30, 2020).