While the tit-for-tat tariff war between the two largest economies in the world seems to have subsided since the Phase 1 deal was agreed upon last December, the strategic competition between US and China is far from an end. Apart from trade measures, the US has leveraged several other weapons against China. Financial and people-to-people decoupling have started in a very targeted way, tech decoupling has made great strides.

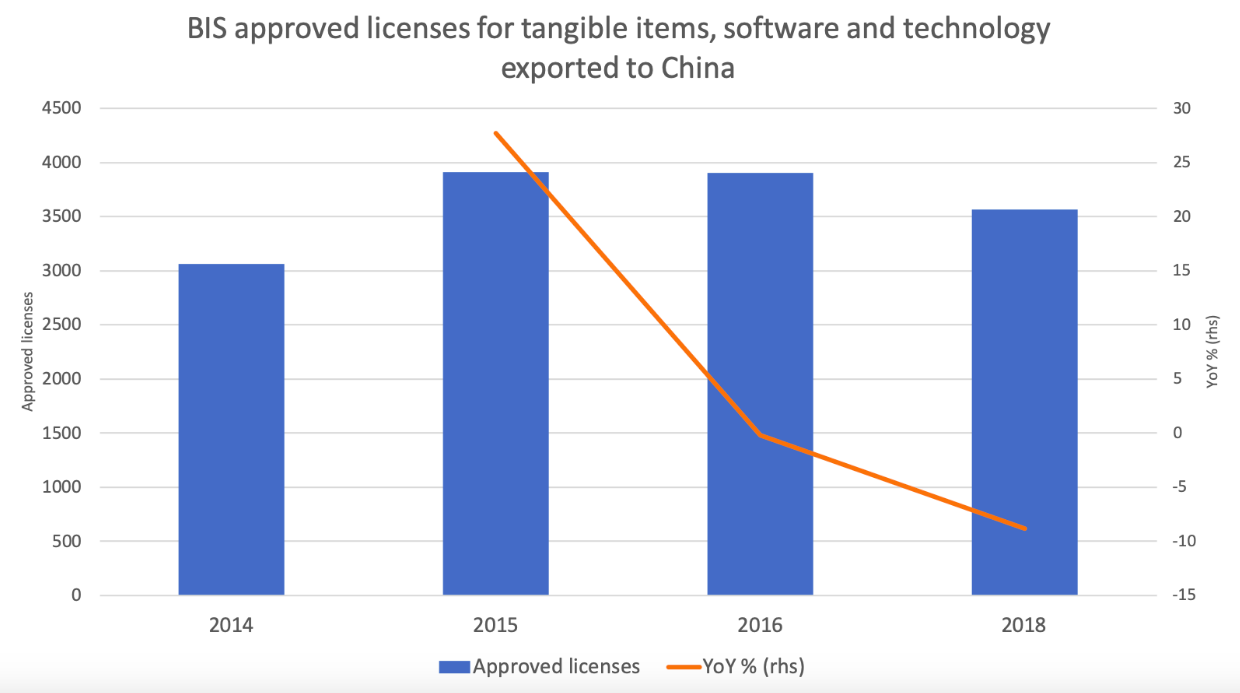

It is hard to pinpoint a date when the tech decoupling between the US and China started. One could go very much back in time when China started banning US social media and other platforms, such as google and facebook. More recently, in the midst of the US-China trade war, one important moment of tension was the house arrest of Huawei’s chief financial officer in Canada in 2018 to comply with a request by the US judiciary to testify on US soil. Given Huawei’s role as the national champion in China’s telecommunication sector, Chinese officials considered this a direct attack to Huawei’s perceived hegemony in 5G. In reality, this is just one of the many ways in which the US tightens control on Chinese technology. For instance, the US has tightened its control over technology transfer into China through the reduction of export licenses on sensitive technology, both into China but also Hong Kong more recently. The process has actually started even before the trade war as Chart 1 shows. To be sure, the number of approvals has been trending downwards since 2015 and has undergone a sharp decline in growth since 2016. In turn, China has recently introduced export licenses into key technologies, such as drones and artificial intelligence.

Beyond trade, the free flow of investment has also been limited, especially as regards technology. This is particularly the case of the US, after the reform of its Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States Committee (CFIUS), with the intent to block an increasing amount of China’s M&A into US, especially on the high-end industrial sector. EU also followed and has finally set up its own investment screening device in April this year, which points to the technology protectionism globally and especially against China in moving up the ladder.

Another important measure taken by the US is the introduction for an entity list, which effectively forbids US companies to conduct business with the Chinese companies in the list. In fact, the US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has published such a list in as early as 1997 on entities deemed risky to US national security. But the names on the list has expanded quickly since 2019 with the addition of Huawei as well a couple of its affiliates and more Chinese corporations. Very recently, China has finally announced the release its own identity list as retaliation but the names of the targeted companies have not been made public. Still, the grounds for the list of targeted entities has been made public, namely having taken discriminatory measures against Chinese businesses on non-commercial grounds. The announced consequences of being in China’s list are not sanctions, as in the case of the US identity list, but rather to be blocked entirely from both trade and investment with China. All in all, both lists are clearly making it harder for Chinese companies to deal with the US but als for any foreign company to deal with China. This can only accelerate decoupling. Tech being one of the key targets of scuh list, makes tech decoupling an even more likely dvelopment.

Another stumbling block in the US-China decoupling which has spilled over to the rest of the world is 5G technology. In fact, after the US banned Huawei from providing 5G platforms in the US, many other countries have followed, such as the UK but also Singapore. As such, the sniped Huawei symbolize the deterred process of technology globalization, which will in turn drive fragmentation of investment, manufacturing and employment.

In addition to the conflicts over technology hardware, the US containment on Chinese technological expansion is moving into software. In early August this year, the Whitehouse published an executive order targeting at Chinese owned social media platforms TikTok as well as WeChat. The measures threaten penalties on U.S. residents or companies engaging in any transactions with these firms after the order is in effect. This is equivalent to the great firewall set up by China much earlier to block its internet users from a handful of applications.

Beyond tech realms, the first steps into financial decoupling could actually support tech decoupling in as far as its financing cross-border becomes more difficult. In fact, Chinese technology firms listed in the US have opted to do a secondary listing to avoid the risk of delisting from the US stock market. This is the case of Alibaba, JD and Netease, which have launched their secondary listing in Hong Kong. Beyond Hong Kong, the Chinese government has adopted policies to encourage the funding domestically for tech companies including the launch of Science and Technology Innovation Board (SSE STAR Market) with loosening regulations. This new market based in Shanghai has the objective of supporting promising tech startups easier equity funding. It, thus, supports China’s industrial policy objectives, especially that of technological upgrade, without havingto rely of foreign stock exchanges where to raise the capital, especially since the biggest such platforms are in the US.

While we are still unsure about the future evolvement of the conflict, the restrictions from the US will only push for China to speed up the development of its own ecosystem in tech. In other words, the upgrade of the Chinese tech industry is more urgent than ever so China will not blink at the related financial costs to support these industries. Another consequence of the above will be for China to rush even more to acquire the necessary technology from the rest of the world. Europe – with much fewer restrictions than the US or even Japan and Korea — will continue to be the most obvious target.

All in all, the creation of two tech ecosystems seems by now relatively unavoidable unless the US elections imply a major change in US approach to China. This seems all the more likely as the US belligerent position on China seems shared by both Democrats and Republicans and, thereby, by President Trump and his contender Biden. On that note, it should be noted that operating with two different ecosystems as regards tech will push other areas, such as finance, trade and foreign direct investment towards more decoupling.