For citation, please use:

Polianskii, M.A., 2021. Russia’s Dissociation from the Paris Charter-Based Order: Implications and Pitfalls. Russia in Global Affairs, 19(4), pp. 36-58. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2021-19-4-36-58

“Russia is fortunately not a member of any alliance.

This is a guarantee of our sovereignty… any nation that is part

of an alliance, gives up part of its sovereignty”

Vladimir Putin (2014)

The international liberal order (ILO) based on international multilateral cooperation is in crisis (Ikenberry, 2020). In the last seventy-five years, more than 200 member states have withdrawn from intergovernmental organizations, with the number of withdrawals in recent decades increasing to an average of one every ten days (von Borzyskowski and Vabulas, 2019). States’ withdrawal from international organizations (IOs), however, is not the only way they can demonstrate their dissatisfaction with the order they are part of. More often, countries choose to dissociate from an order, in which they intentionally distance themselves from the core rules and norms of institutions, sometimes still remaining formally committed to them (Morse and Keohane, 2014). Yet, dissociations can have very tangible consequences for the parties involved by significantly exacerbating tensions and even leading to a full-blown international crisis, as the Ukraine conflict and the ensuing confrontation between Russia and the West vividly demonstrates.

Even though the processes of dissociation are actively discussed by politicians, research on this topic is lagging behind, as scholars have traditionally focused more on their creation than their decay (Krasner, 1983; Keohane, 1984). Only in recent years has the academic debate begun to acknowledge more explicitly that international institutions, too, can face severe crises (Dembinski and Peters, 2019). That said, attempts to explain such crises have mostly been limited to trying to establish the absence of the factors that led to the creation of respective IOs (Webber, 2014; Schimmelfennig, 2017; Börzel and Risse, 2018). The present study aims to bridge the gap regarding the “exit stage” by drawing a distinction between the rationale behind states’ involvement in an IO and the centrifugal dynamics that emerges in the process of integration. Specifically, the author looks into the character of the issues that lead to states’ dissociation by differentiating between material and ideational conflicts. Material problems comprise those groups of issues where parties have tangible interests (often military), whereas ideational problems are those that have no material substance and are epitomized by ideological clashes, identity concerns and the like. Using an established understanding of international institutions as “persistent and connected sets of rules that prescribe behavioral roles, constrain activity, and shape expectations” (Keohane 1988, p. 386) this study analyzes the causes of dissociation by paying particular attention to the way the two aforementioned dimensions influence a state’s rationale to leave a normative order.

The crisis of the Paris Charter-based order (1990) as a result of Russia’s dissociation from it represents an excellent case study to explore the logic of dissociation for two major reasons. First, as Russia’s dissociation has pronounced material and ideational dimensions (Dembinski and Polianskii, 2021), the paper can weigh the salience of these two problem areas against each other to determine which factors influenced Moscow’s decision to dissociate the most. Second, since Russia’s dissociation has culminated in a dramatic growth of overall tensions in the wake of the Ukraine crisis in 2014, the study also conducts a preliminary analysis of how serious dissociation can be for the dynamics of tensions between Russia and the West. The author intends to explore the specific interconnection between dissociation and the tensions between “leavers” and “remainers” throughout various stages of dissociation in future studies.

For the purposes of this paper, the term ‘West’ is defined as a community historically encompassing NATO (without Turkey) and the EU member states. Although this might be seen as too broad an interpretation, it corresponds both to the understanding of the term in the Russian discourse (Tsygankov, 2007) and in the academic literature (Neumann, 1999). While acknowledging that Russia’s dissociation from the Paris Charter-based order also has a distinct interactional aspect between the motives of the two sides, the focus of the present study is limited to Russia’s rationale only, leaving the Western perspective for further research endeavors.

To answer this question, the paper offers an informed institutional reading of relations between Russia and the West that resulted in Ukraine’s “big bang” in 2014, the epitome of Russia’s dissociation, on the one hand, and on the other, develops a theoretical argument concerning the driving forces of dissociation, differentiating between ideational and material dimensions. The paper proceeds as follows: first, the author sketches out the contours of the Paris Charter-based order, focusing on the expectations and hopes that Russia had when interacting with the West in the framework of multilateral institutions. The article then moves on to an analysis of the material-ideational dichotomy of the European security institutional set-up and Russia’s frustrations with this arrangement. In the last part, the study explores the case studies represented by Moscow’s security concerns, on the one hand, and its self-conception as a great power, on the other, to illustrate how these two dimensions contributed to Russia’s dissociation from the Paris Charter-based order.

The Depth and Nature of Russia’s Involvement in the Paris Charter-Based Order

To understand why Russia constantly refers to its past frustrations with the West when justifying its current policies, the study examines how this relationship developed after the end of the Cold War and what expectations Moscow had while integrating into Western-led institutions.

The Russian Federation was never a full-fledged part of the European security system (De Haas, 2010; Kortunov, 2016). The country’s leadership did, however, inherit Paris Charter rights and obligations from the Soviet Union, which secured its role as a central player in the field of European security. The Paris Charter, signed by former Cold War antagonists at a summit of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) in 1990, determined the contours and principles of the new European order. It emphasized common security and the peaceful resolution of conflicts, on the one hand, and underlined the importance of liberal democratic norms, on the other. The former principles of the Charter implied that the security space was indivisible and that a threat to the security of any participating state was inextricably linked to the security of all others (Charter of Paris for a New Europe, 1990). The latter pillar of the Paris Charter-based order postulated the signatories’ commitment to “consolidate and strengthen democracy as the only system of government of their nations” as well as respect “sovereign equality” of every member, and thus also their freedom to choose their own security arrangements (ibid). Consequently, alongside the principle of indivisible security (which Russia favored the most), the universality of liberal democratic values, as demanded by the West, was equally important for building a new Europe on the basis of the Paris Charter (Forsberg, 2019).

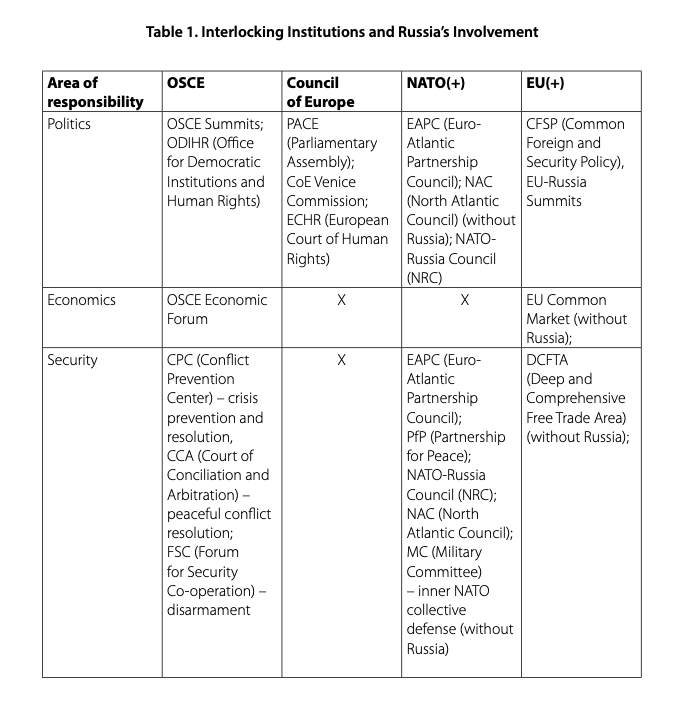

Owing to the speed of the collapse of the Soviet Union that occurred shortly after the Charter’s ratification, the signatories decided to take stock of the existing IOs that were to ensure the fulfilment of the aforementioned contradictory principles. These organizations were the Conference (Organization since 1995) on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE/OSCE), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU) as well as the Council of Europe (CoE) (Forsberg and Haukkala, 2015). Flanked by the inclusion of Russia in “prestigious” forums like the G7/8, each of the four multilateral organizations was supposed to create a system of interlocking/overlapping institutions, despite their different roots and aims (see Table 1). Moscow’s experiences and expectations of each of these platforms varied and the present study will briefly examine this below.

Russia’s hopes for building a common post-Cold War European project were primarily pinned on the OSCE. Apart from being a founding member of this IO, Russia had numerous allies from the post-Soviet space in the organization, with which it frequently built coalitions and put forward new initiatives against the Western bloc (Kropatcheva, 2012). Given that the OSCE was, in Russia’s eyes, the only genuinely pan-European organization, Moscow expected it to become the main pillar of the emerging European institutional security order, arching over all other IOs and playing a “key integrating role” between former adversaries (OSCE, 1999). Russia actively lobbied the idea, presented at the OSCE Istanbul Summit in 1999, of creating a “flexible coordinating framework” of European security with no “hierarchy of organizations or a permanent division of labor among them” (ibid). Even though these ideas did not become reality due to the ensuing tension surrounding frozen conflicts in the post-Soviet space, Russia still actively employed the organization’s mechanisms in mediating the numerous conflicts that kept springing up along its borders until the early 2000s (e.g., OSCE missions in Nagorno-Karabakh, Transnistria etc.). After it had transformed from a Conference into an Organization, the OSCE established permanent and independent dialogue platforms which were represented by three “baskets”: military, economic, and human security. Negotiations on these issues were separated from each other, unlike during the Cold War (after 1975), when the Soviet Union often had to make compromises on human rights issues to make any progress on disarmament. In the 1990s, this opened a window of opportunity for Russia to stabilize its western neighborhood through the arms reduction treaties (Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty, CFE) and confidence-building measures (Open Skies Treaty).

NATO was initially designed as a collective defense organization to provide security through deterrence vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. After the disappearance of its main antagonist, however, the Alliance found itself in an ideological crisis and attempted to reinvent itself as a global collective security organization (Yost, 1998). This was reflected in NATO’s active involvement in crisis management in Europe and beyond, as well as in the introduction of enhanced stability programs between the Alliance and its partner countries (Forsberg and Haukkala, 2015). Against the background of the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the emerging security vacuum in Eastern Europe, the Russian leadership (after realizing quite soon that hopes of NATO’s reciprocal dissolution were too far-fetched) actively tried to establish cooperation with the “renewed” Alliance in order to secure its zone of influence in the region. With this aim in mind, Russia joined the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC), a post-Cold War NATO institution, initially hoping that this forum might become an all-encompassing European security organization where Russia would be a full-fledged member. The Yeltsin/Kozyrev team attempted to become part of the “first wave of accession” by joining the Partnership for Peace (PfP) program in 1994 when the U.S. leadership took the decision to expand into Eastern Europe (Forster and Wallace, 2001). In addition, the NATO-Russia Founding Act (1997) was signed to facilitate the exchange of information, promote consultation, and generally reduce the transaction costs incurred by the two parties associated with joint peacekeeping efforts. In 2002, the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) with its G20 concept (19 member states in national capacity and Russia) was founded, which was seen in Moscow as a cornerstone platform for cooperation and the provision of a common security space. In the same year, President Putin even welcomed plans for NATO enlargement as Moscow saw it as a step to create an “enlarged common area” for cooperation (quoted in Warren, 2002).

Cooperation with the European Union was also regarded by Moscow as an additional instrument embodying the spirit of the Paris Charter through economic cooperation and political consultation. Despite being shaped by asymmetrical cooperation, interaction with the EU was marked by healthy pragmatism (Neumann, 1998). The milestone Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA), ratified in 1997, created a framework for comprehensive cooperation at the economic, political, and civil society levels. In addition to the existing annual Russia-EU summits, the EU-Russia Permanent Partnership Council was created in 2003, which became a valuable addition to an extremely comprehensive system of exchange platforms, including a “common space” on security issues. Regular meetings were held at the level of foreign ministers (twice a year), political directors (four times a year) and foreign policy experts (Forsberg and Haukkala, 2016, p. 27). Russia was the only non-EU state with which Brussels had so many high-ranking exchange platforms, and this visibly satisfied Moscow’s status ambitions. Even after numerous Eastern European countries’ admission to the EU in 2004 and the conflict around Russian transit to Kaliningrad (Russia’s exclave on the Baltic Sea), relations between Russia and the EU still remained pragmatic and mutually beneficial. In 2009, former NATO Secretary General Javier Solana described Russian-European relations as “fantastically” stable (quoted in Arbatova and Dynkin, 2016) despite the impact of the Russo-Georgian War in 2008 and the failure to renegotiate the PCA agreement a few years before that. The Medvedev era ushered in some hope for the renewed development of multilateral cooperation with the EU when in 2009, the Partnership for Modernization (P4M), a German initiative, was launched. Building on this initiative, both sides managed to revive some structures of institutionalized cooperation, which had some, albeit limited, trust-building spill-over effects on security.

Finally, Russia’s engagement with the Council of Europe (CoE) rested on the logic of building stability in Europe through the “human” dimension. After having been admitted to the CoE in 1996 and having ratified the European Convention on Human Rights two years later, Moscow initially signaled that it did not have any problems with fulfilling its obligations in the human rights domain (Zagorskiy, 2021). It abided by the rules of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), adopted a new criminal code, passed laws regulating the activities of the office of the prosecutor general, and created the post of commissioner for human rights (Busygina and Kahn, 2019, p.70). At a later stage, however, Russia expected that in exchange for its progress towards liberal democratic values, the West would also take certain steps, especially concerning NATO expansion in Eastern Europe. Being a nuclear superpower, however, Moscow definitely did not consider the implementation of liberal democratic norms or convergence with “Western” civilizational standards to be defining elements in determining its status and position in the Paris Charter-based order.

Moscow’s foreign policy is often described as essentially realist (Lynch, 2001; Simionov, 2017) and solely dependent on force and power in relations with foreign actors. Yet, no other major power in Europe created and became involved in more IOs after the end of the Cold War than Russia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia established the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and BRICS. Russia even tried to establish relations with the Western European Union in the 1990s, became a member of the G20, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and was almost admitted into the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2013. Although not all of these IOs deal with security-related issues and many of them developed separately from the wider European network, Russia’s involvement in these institutions demonstrates that in its foreign policy, Moscow relies on international institutions more than is usually assumed (Istomin, 2021). Despite the fact that the scope of the present study is limited to Russia’s relationship with the West in the context of NATO, the EU, the OSCE, and the CoE, the author considers the aforementioned cases of Russia’s engagement with multilateral platforms more than enough to posit that the former’s dissociation from the Paris Charter-based order was not driven by its alleged general dismissal of IOs in international politics. The motivation for this move comprised different factors, which the study focuses on in the next subchapter.

The Reasons Behind Russia’s Dissociation: The Dichotomy of the Material and the Ideational

Having outlined the nature of Russia’s integration into the Paris Charter-based order and the expectations that accompanied it, the study now analyzes the essence of the problems and frustrations that Moscow experienced throughout the process of integration, differentiating between material and ideational problems.

From the early 2000s onwards, a sense of disappointment and disillusionment pervaded the overall atmosphere in Western-Russian relations. This was already reflected in Vladimir Putin’s address to the German Parliament in 2001, where he noted: “…we talk about partnership, but in practice we have not learned to trust each other” (Putin, 2001). The lack of trust in Russia was, in Putin’s eyes, directly tied to the West’s cautious and “leisurely” approach to the integration of its former adversary, illustrated by the way in which the visa-free regime negotiations were carried out, for example. Not only was this somewhat reminiscent of the Cold War but it was also very humiliating for Moscow, as it implied that the West first expected Russia to “become civilized” by fulfilling obligations under the EU-Russia cooperation agreement (Baysha, 2018).

Throughout his first two presidential terms, Putin demonstrated that he could never accept the implementation of Western liberal democratic values as a precondition for a good mutual relationship. The “Democracy first—cooperation later” formula, especially as Brussels did not allow Moscow to substantially influence any decision-making mechanisms of NATO or the EU (Zagorskiy, 2017, p.68), hardly corresponded with Putin’s vision of this integration. And negotiations about “how fast” and “how exactly” Russia should unilaterally adapt to normative expectations of the West were never on Putin’s agenda (Lukyanov quoted in House of Lords 2015, p. 23). In short, from Russia’s perspective, the fundamental post-Cold War process was rather supposed to be one of mutual transformation, which was contrary to the Western perspective of a rather straightforward process of enlargement and Russia’s unilateral adoption of liberal democratic ideals.

Russia’s convergence with the West’s civilizational standards (especially in the domain of individual rights and freedoms), however, was the key factor for the West when it came to determining Russia’s place in this order, an approach Russia strongly disagreed with.

Furthermore, not only did the principle of sovereign equality anchored in the Paris Charter-based order not allow Moscow to dictate how its former “satellites” should go about their security arrangements, but later also allowed the latter to demand accession to NATO, based on the argument that Russia was a major threat to their security. Thus, the declarative principle of sovereign equality that Russia originally saw as securing its own position vis-à-vis the West in the circumstances of the crumbling Soviet system, was, in Moscow’s eyes, ultimately used against it as a pretext for NATO’s enlargement.

Admittedly, Russia might have had (unjustifiably) high hopes when it came to the West’s readiness to acknowledge and accept its ambitions and expectations. But this does not change the fact that when Putin returned to the Kremlin for his third presidential term in May 2012, the Paris Charter came to be seen as a document indicating Russia’s “indirect submission” to the West (Ensel, 2020). In Putin’s view, Russia should not have “trust[ed] the West too much” as it was later betrayed for that (Putin, 2017). Thus, we argue that roughly one year before the Ukraine crisis began, the “double-faced” Paris Charter-based order had already reached its moment of truth. Its spectacular collapse, ushered in in the wake of the Euromaidan, was mainly predetermined by the fact that the West failed to establish an inclusive security system with Russia that would leave behind the Cold War mentality (Sakwa 2017). And the “irony” of this order is not that it failed to prevent the Ukraine crisis from erupting, but that the dichotomy inherent in it might even have contributed to its own eventual collapse (Hill, 2018).

To demonstrate how Russia’s dissatisfaction and frustrations led to its complete dismissal of the Paris Charter principles poses a fundamental challenge. By examining how exactly the different dimensions of this institutional order contradicted Russia’s identity concerns and national security considerations, the present study illustrates how the principles of the Paris Charter eventually legitimized policies that ran counter to perceived Russian interests in Europe.

The Paris Charter as a Threat to Russia’s National Security Interests

National interests (understood in this paper as material issues) have, more often than not, coexisted with the ideological rationale in Russian foreign policymaking vis-à-vis the West (Trenin, 2021). Nonetheless, this study tries to differentiate between these types of issues and demonstrate how each contributed to Russia’s belief that the Paris Charter-based order was skewed and biased.

Ensuring security and stability on the western border has traditionally been the primary task of every Russian leader for the last three centuries (Danilov, 2021). After the end of the Cold War, participation in the Western multilateral institutions was seen as one of the instruments to attain this goal. The OSCE was instrumental in reducing the military budget (through arms control agreements) as well as in settling conflicts in the post-Soviet space (e.g., the mission in Transnistria), while multilateral cooperation with the United States and NATO helped to determine the fate of the Soviet nuclear arsenal in Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. Apart from stabilizing the post-Soviet space, Western assistance also helped to free Moscow’s hands to deal with domestic security threats, such as the separatists in the North Caucasus (Trenin, 1996). This cooperation, however, had an extremely ambiguous character that was defined by NATO’s evolving role and the West’s initially uncertain position on Eastern Europe (Istomin, 2018). But as this ambiguity began to evaporate, and, after three waves of expansion, NATO’s intentions as a collective defense organization became more obvious, Russia’s opposition to the Alliance also crystallized into more concrete forms.

Despite the fact that the NATO expansion was initially framed by Putin as an “enlarged common area,” it was later perceived in Russia as a “national humiliation” (Karabeshkin and Spechler, 2007). NATO’s enlargement in Eastern Europe, a region which had long been Moscow’s sphere of influence, posed a fundamental challenge to Russia’s ability to project its power and ensure its dominance in what it considered a “zone of privileged interests” (Trenin, 2009). Although with each step of enlargement, NATO’s combined military potential in Europe gradually decreased (Marten, 2020, p. 407) in Russia’s eyes it did not change the fact that a historically adversarial alliance was deploying its troops in the proximity of Russia’s border (not to mention the loss of the market for the military-industrial complex with the shift to NATO military standards).

When, during the NATO Summit in Bucharest in 2008, the Alliance promised Ukraine and Georgia that they would become full-fledged NATO members, Russia saw the West as having crossed a red line. By allowing these states to join NATO, in Russia’s eyes, the Alliance undermined the country’s “hard” security interests by failing to acknowledge Moscow’s perceived great power status with its own legitimate zone of influence. Russia struggled to understand the logic of NATO’s enlargement as the Alliance’s “fulfilling the individual ambitions” of East European states for more security, democracy and rule of law, instead framing it as Western Realpolitik in the common neighborhood. Aggravated by the wave of color revolutions that took over the post-Soviet space, even the most progressive people in Moscow started voicing concerns about malicious Western ambitions in the post-Soviet space (Tsygankov, 2021). These fears and frustrations were reflected in Putin’s emotional Munich speech, where he openly expressed his discontent with American supremacy, accusing it of constantly ignoring Russia’s national interests: “The United States has overstepped its national borders in every way. This is visible in the economic, political, cultural and educational policies it imposes on other nations. Well, who likes this? Who is happy about this?” Shortly after this speech, the harsh rhetoric was followed by equally radical actions, with Russia resuming flights of its strategic nuclear bombers after a 15-year break (Kramer, 2007). In 2007, Russia also suspended its participation in the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE).

As a result, although at first, Russia saw Western-led security institutions as one of the means of solving the security-related issues it was not in a position to tackle alone, from the late 2000s, Russia became aware that the West’s security vision did not coincide with its own.

Identity Concerns as an Enabler of Russia’s Dissociation

Despite having lost its status as one of the global superpowers with the collapse of the USSR, Russia did not, however, lose its sense of being a great power, a self-perception which still played a key role in Russia’s relations with the West and in the world at large (Splidsboel-Hansen, 2002, p. 416). Accessing Western institutions both at home (introducing a market economy, democratic practices, etc.) and abroad (i.e., Council of Europe) was seen as a central instrument for maintaining this status. Having retained its permanent seat on the UN Security Council, Russia never considered itself as having been defeated in the Cold War. Both Gorbachev and Yeltsin argued that the Soviet Union did not lose the Cold War since the end of the confrontation was ushered in by the “new thinking” on both sides and not by the victory of the United States. Accordingly, Moscow expected to occupy an equal and prominent position in the new European and global order as a great power that it considered itself to be. It also wanted to be seen by the West as an equal partner and expected the West to adapt to Russia’s specific ambitions in the Paris Charter-based order. Recent studies indicate that up until the mid-1990s, Russian elites did not have strong anti-Western sentiments and were genuinely ready to cooperate with the United States to become a normal Western European country (Sokolov et al., 2018). This did not mean, however, that they were prepared to abandon their great power aspirations, despite the significant economic downturns and political troubles at home. What they failed to grasp, however, was that “…the political structure of the modern West, which emerged in the 1940s, was and still is based on the unconditional leadership of one country—the United States. There could be no other great power in the united West” (Trenin, 2021).

While Russia was hoping to become a sort of “vice president” in this order, in the eyes of the West, its reduced capacity did not even qualify it for a second-tier status in the new ranking system, as status and recognition were awarded in accordance with the implementation of “civilizational standards” and not sheer military power or territory. When Moscow’s elites realized this in 1994-1995, their criticism of the order became more explicit. This did not automatically lead to a sharp downturn in relations with the West, but Moscow became more vocal about its discontent with the fact that it had fulfilled Western requirements and yet had still not received what it had expected. Consequently, as the EU itself had consistently ignored its own declared values in its relations with Russia, the Kremlin, for its part, dismissed the Western emphasis on human rights commitments as cynical (Forsberg and Haukkala, 2016). And when the West invoked the Paris Charter and Russia’s obligation under this document, Moscow saw this as Brussels’ intentionally disregarding Moscow’s right as a great power to independently decide how to organize its domestic politics.

But the ideational conflicts were not limited to the domestic domain only. The aforementioned waves of NATO enlargement, apart from being a purely materialistic issue opened another Pandora’s box: the Kremlin saw deployment of military infrastructure in the region as yet more proof of Western distrust towards Russia and its intentions, particularly regarding its ambitions in Eastern Europe. Moscow realized that the viability of the Alliance’s (primarily American) security assurances to the Eastern European states rested squarely on the exclusion of Russia from NATO (Danilov, 2021). In other words, the accession of Eastern European states (with the simultaneous exclusion of Russia from this process) proved to Moscow that it was still seen as the main ideational antagonist in the transatlantic community.

Russia’s “great power” identity continuously evolved around its positioning towards European/Western institutions (starting with the Concert of Europe after the Congress of Vienna in the 19th century), and gaining access to European multilateral institutions after the end of the Cold War was initially seen as an instrumental step in recovering from the perceived loss of status caused by the collapse of the USSR. However, as it became clear to Moscow that the requirements of occupying a prominent position in that order (and thus acquiring status) did not correspond to Russian cost-benefit expectations, it started looking for other ways to obtain status outside of that framework. Subsequently, the Kremlin embraced its perceived great power status by saying “no” to the West and advancing its status in opposition to Western structures (Tsygankov, 2016). Russia now feels comfortable openly challenging the authority of Western institutions: around 70 percent of all ECHR rulings are pending in Russian courts (Council of Europe, 2021).This resistance gives Russia a feeling of being taken more seriously by the West than it was in the past when it fully complied with its ideological obligations.

Today the Kremlin no longer considers committing itself to Western-dominated European institutions instrumental in sustaining its great power identity, as the price it must pay for this is higher than any ideational benefits it can reap from further integration.

* * *

Moscow’s experience with multilateral European security institutions in the first twenty years after the end of the Cold War led it to believe that both its material and ideational interests were better served outside of these structures. The Paris Charter, which was once seen as a document that would secure Moscow’s right and proper place in the post-bipolar regional order, was later perceived as being skewed towards the West, to Russia’s detriment. This dissatisfaction gave rise to growing tensions that came to a head in Ukraine in 2014, leading to a confrontational shift in the logic of relations between Russia and the West.

At the same time, the growing tensions between Russia and the West within the European institutions in question do not seem to reflect Moscow’s general distaste for IOs but rather its accumulated frustrations with its counterpart in them. This explains the consistent deterioration of relations across all the four analyzed institutions at the same time, while Russia’s multilateral cooperation in other regions has remained intact. Against this background, there is reason to assume that European institutions could still be instrumental in resolving the conflict in one form or another if the general atmosphere between the two actors were to improve.

Recent research indicates that Russia is in fact far from being an out-and-out revisionist and anti-Western power (Istomin, 2020; Romanova, 2018), and neither does the Western institutions’ raison d’être seem to be centered on Russia’s destruction either (Moens and Richards, 2020). This assumption begs the question, however: If the Paris Charter-based order almost collapsed within a matter of days after the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis, how advisable is it to build a new system of rules on the basis of this fragile architecture? Various scholars on both sides argue that European security institutions are outdated and that Russia and the West would be well-advised not to repeat the mistakes of the past by trying to strengthen relations with the West through institutions that continue to reproduce the confrontation (Karaganov, 2018). Indeed, some of the remnants of these institutions could be used instrumentally to anchor emerging norms, principles and institutions but should be abandoned when a new system and its institutions finally take shape (Dembinski and Spanger, 2017). Opponents of this approach in the West, however, are “monistically” sure that these old institutions can still provide a sustainable framework for stability in the continent and that Russia should return to the old rules of the game (Sakwa, 2018). By so doing, however, they ignore Moscow’s absolute reluctance to return to “business as usual,” as the Paris Charter-based order is perceived as genuinely unjust and even threatening Russia’s national security and ideational interests.

If the West continues to fail to acknowledge Russia’s frustration, which eventually led to the desperate dissociative act in 2014, Moscow is likely to continue to challenge the basis of the European order and sabotage the West (cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, etc.). Since, for Russia, committing itself to the norms and principles of the Paris Charter in 1990 essentially symbolized joining the wider international liberal order (Bordachev, 2021), the consequences of dissociation for the Paris Charter principles can potentially reverberate beyond Europe. Thus, by analyzing Russia’s past interactions with the West through NATO, the EU, the OSCE, and the CoE, this paper sought to explain why Russia sees its interests as better served in Europe outside the Paris Charter. The global consequences of this development, however, are yet to be explored.

Arbatova, N.K. and Dynkin, A.A., 2016. World Order after Ukraine. Survival, 58(1), pp. 71-90.

Baysha, O., 2018. Miscommunicating Social Change: Lessons from Russia and Ukraine. 1st Edition. Lexington Books.

Bordachev, T., 2021. The Charter of Paris and a New European Order. Russia in Global Affairs, 19(1), pp.12-31. Available at: eng.globalaffairs.ru/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/012-031.pdf [Accessed 1 Septembeer 2021].

Börzel, T. and Risse, T., 2018. A Litmus Test for European Integration Theories: Explaining Crises and Comparing Regionalisms [online]. Persistent Identifier (PID). Available at: nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-57753-6 [Accessed 1 September 2021].

von Borzyskowski, I. and Vabulas, F., 2019. Hello, Goodbye: When Do States Withdraw from International Organizations? Review of International Organizations, 14(2), pp. 335-366.

Busygina, I. and Kahn, J., 2019. Russia, the Council of Europe, and “Ruxit,” or Why Non-Democratic Illiberal Regimes Join International Organizations. Problems of Post-Communism, 67(1), pp.64-77.

Charter of Paris for a New Europe, 1990. Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) [online]. Available at: https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/0/6/39516.pdf [Accessed 9 September 2021].

Council of Europe, 2021. Country Factsheet for the Execution of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. Department for the Execution of Judgemeents of the European Court of Human Rights.

Danilov, D., 2021. Interview with the Author. Personal interview.

Dembinski, M. and Peters, D., 2019. Dissoziation als Friedensstrategie? Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen, 26(2), pp. 88-105.

Dembinski, M. and Polianskii, M., 2021. Russia and the West: Causes of Tensions and Strategies for Their Mitigation. Russia and Contemporary World, 110(1), pp. 5-19.

Dembinski, M. and Spanger, H., 2017. ‘Plural Peace’-Principles of a New Russia Policy [online]. Available at: www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/53452 [Accessed 3 September 2021].

Ensel, L., 2020. 30 Jahre ‘Charta von Paris’ oder: Wurde der Kalte Krieg eigentlich jemals beendet? Telepolis [online]. Available at: www.heise.de/tp/features/30-Jahre-Charta-von-Paris-oder-Wurde-der-Kalte-Krieg-eigentlich-jemals-beendet-4963769.html [Accessed 16 August 2021].

Forsberg, T., 2019. Russia and the European Security Order Revisited: From the Congress of Vienna to the Post-Cold War. European Politics and Society, 20(2), pp. 154-171.

Forsberg, T. and Haukkala, H., 2015. The End of an Era for Institutionalism in European Security? Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 23(1), pp. 1-5.

Forsberg, T. and Haukkala, H., 2016. The European Union and Russia. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

Forster, A. and Wallace, W., 2001. What Is NATO For? Survival, 43(4), pp. 107-122.

De Haas, M., 2010. Medvedev’s Alternative European Security Architecture. Security and Human Rights, 21(1), pp. 45-48.

Hill, W.H., 2018. No Place for Russia: European Security Institutions since 1989. Columbia University Press.

House of Lords, 2015. The EU and Russia: Before and Beyond the Crisis in Ukraine. Authority of the House of Lords [online]. Available at: cursdeguvernare.ro/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/115.pdf [Accessed 16 August 2021].

Ikenberry, G.J., 2020. The Next Liberal Order. Foreign Affairs, 99, pp. 133-143 [online]. Available at: www.reteccp.org/primepage/2020/demousa20/thenext.pdf [Accessed 2 September 2021].

Istomin, I., 2018. Negotiations under Disagreement: Limitations and Achievements of Russian-Western Talks on NATO Enlargement. In: F.O. Hampson and M. Troitskiy (eds.) Tug of War. Negotiating Security in Eurasia. Centre for International Governance Innovation, pp. 35-52.

Istomin, I., 2020. Rossiya kak derzhava status-kvo [Russia as a Status-Quo Power]. Rossya v globalnoi politike, 18(1), pp. 30-38 [online]. Available at: globalaffairs.ru/articles/rossiya-kak-derzhava-status-kvo/ [Accessed 2 September 2021].

Istomin, I., 2021. Interview with the Author. Personal interview.

Karabeshkin, L.A. and Spechler, D.R., 2007. EU and NATO Enlargement: Russia’s Expectations, Responses and Options for the Future. European Security, 16(3–4), pp. 307-328.

Karaganov, S., 2018. On the Struggle for Peace [online]. Available at: karaganov.ru/content/images/uploaded/f2d9088fd3ea226d8b26ef2b113c5d06.pdf [Accessed 9 Septrember 2021].

Keohane, R.O., 1984. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Keohane, R.O., 1988. International institutions: Two approaches. International Studies Quarterly, 32, pp.379–396 [online]. Available at: academic.oup.com/isq/article-abstract/32/4/379/1805478 [Accessed 1 September 2021].

Kortunov, A., 2016. The Inevitable, Weird World. Russia in Global Affairs, 14(4), pp. 8-19 [online]. Available at: eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/the-inevitable-weird-world/.

Kramer, A.E., 2007. Russia Resumes Patrols by Nuclear Bombers. The New York Times, 18 August [online]. Available at: www.nytimes.com/2007/08/18/world/europe/17cnd-russia.html [Accessed 11 September 2021].

Krasner, S., 1983. International Regimes. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Kropatcheva, E., 2012. Russia and the Role of the OSCE in European Security: A ‘Forum’ for Dialog or a ‘Battlefield’ of Interests? European Security, 21(3), pp. 370-394.

Lynch, A.C., 2001. The Realism of Russia’s Foreign Policy. Europe — Asia Studies, 53(1), pp. 7-31.

Marten, K., 2020. NATO Enlargement: Evaluating Its Consequences in Russia. International Politics, 57(3), pp. 401-426.

Moens, A. and Richards, A., 2020. NATO: Current Challenges and Long-Term Adaptation. In: Routledge Handbook of Peace, Security and Development. Taylor and Francis, pp. 322-334.

Morse, J.C. and Keohane, R.O., 2014. Contested Multilateralism. The Review of international Organizations, 9(4), pp. 385-412.

NATO and the Russian Federation, 1997. Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation signed 27-May [online]. Available at: www.nato.int/cps/cn/natohq/official_texts_25468.htm [Accessed 18 August 2021].

Neumann, I., 1998. Russia as Europe’s Other. Journal of Area Studies, 6(12), pp. 26-73.

Neumann, I., 1999. Uses of the Other: ‘The East’ in European Identity Formation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

OSCE, 1999. Charter for European Security and the Platform for Co-operative Security [online]. Available at: www.osce.org/de/node/125809 [Accessed 3 September 2021].

Putin, V., 2001. Speech in the Bundestag of the Federal Republic of Germany. President of Russia: Kremlin.ru [online]. Available at: www.en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/21340 [Accessed 17 August 2021].

Putin, V., 2014. Security Council Meeting. President of Russia: Kremlin.ru [online]. Available at: en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/46305 [Accessed 2 September 2021].

Putin, V., 2017. Vladimir Putin Meets with Members of the Valdai Discussion Club. Transcript of the Plenary Session of the 14th Annual Meeting. Valdai Club [online]. Available at: valdaiclub.com/events/posts/articles/putin-meets-with-members-of-the-valdai-club/ [Accessed 9 September 2021].

Romanova, T., 2018. Russia’s Neorevisionist Challenge to the Liberal International Order. The International Spectator, 53(1), pp. 76-91.

Sakwa, R., 2018. One Europe or None? Monism, Involution and Relations with Russia. Europe-Asia Studies, 70(10), pp. 1656–1667 [online]. Available at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09668136.2018.1543762 [Accessed 9 September 2021].

Schimmelfennig, F., 2017. Theorising Crisis in European Integration. In: D. Desmond, N. Nugent and W.E. Paterson (eds.) The European Union in Crisis, pp. 316-336 [online]. Available at: www.researchgate.net/profile/Frank-Schimmelfennig/publication/318591049_Theorising_Crisis_in_European_Integration/links/59db2242458515a5bc2d6e24/Theorising-Crisis-in-European-Integration.pdf [Accessed 1 September 2021].

Simionov, L., 2017. The EU and Russia Shifting Away from the Economic Logic of Interdependence: An Explanation Through the Complex Interdependence Theory. European Integration Studies, (11), pp. 120-137.

Sokolov, B., Inglehart, R.F., Ponarin, E., Vartanova, I. and Zimmerman, W., 2018. Disillusionment and Anti-Americanism in Russia: From Pro-American to Anti-American Attitudes, 1993–2009. International Studies Quarterly, 62, pp. 534-547. Available at: academic.oup.com/isq/article-abstract/62/3/534/5045351 [Accessed 1 September 2021].

Splidsboel-Hansen, F., 2002. Russia’s Relations with the European Union: A Constructivist Cut. International Politics, 39(4), pp. 399-421.

Trenin, D., 1996. Russia’s Security Interests and Policies in the Caucasus Region. In: B. Coppieters (ed.) Contested Borders in the Caucasus. Brussles: VUB University Press, pp. 67-76 [online]. Available at: www.vub.be/sites/vub/files/nieuws/users/bcoppiet/131trenin.pdf [Accessed 1 September 2021].

Trenin, D., 2009. Russia’s Spheres of Interest, Not Influence. Washington Quarterly, 32(4), pp. 3-22.

Trenin, D., 2021. New Balance of Power: Russia in the Search of Foreign Policy Equilibrium. 1st Edition. Moscow: Alpina Publisher.

Tsygankov, A., 2016. Crafting the State-Civilization. Vladimir Putin’s Turn to Distinct Values. Problems of Post-Communism, 63(3), pp. 146-158. Available at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10758216.2015.1113884 [Accessed 1 September 2021].

Tsygankov, A.P., 2007. Finding a Civilisational Idea: ‘West,’ Eurasia,’ and ‘Euro-East’ in Russia’s Foreign Policy. Geopolitics, 12(3), pp. 375-399.

Warren, M., 2002. Putin Lets NATO “Recruit” in Baltic. The Telegraph [online]. Available at: www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/1398379/Putin-lets-Nato-recruit-in-Baltic.html [Accessed 1 September 2021].

Webber, D., 2014. How Likely Is It that the European Union Will Disintegrate? A Critical Analysis of Competing Theoretical Perspectives. European Journal of International Relations, 20(2), pp. 341-365. Available at: journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1354066112461286 [Accessed 1 September 2021].

Yost, D., 1998. The New NATO and Collective Security. Survival, 40(2), pp. 135-160. Available at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00396338.1998.10107847 [Accessed 9 September 2021].

Zagorsky, A., 2017. Russia in the European Security Order. Primakov National Research Institute of World Economy and International Relations, (IMEMO), Moscow.