For citation, please use:

Mukhia, A., Zou, X., 2022. Mapping India’s (Re)Сonnection to Eurasia. Russia in Global Affairs, 20(2), pp. 184-204. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2022-20-2-184-204

India’s interest in Eurasia (excluding the EU) grew seriously after foreign affairs analyst Lieutenant Colonel Dianne L. Smith called the Central Asian region a “New Great Game,” a strategic competition between major powers (Smith, 1996). The Central Asian region was traditionally perceived as “India’s extended neighborhood,” an area extending beyond South Asia, which, due to geopolitical and geoeconomic importance, has historically been the object of a tussle for great powers (Scott, 2009, p. 107). It was also called the “heart of Eurasia,” which for many countries—China, Russia, India, the U.S., and European states—served as a pivot for geopolitical transformations (Wani, 2020).

India started to build ties with the countries of the region in early 1993 when then Prime Minister Narasimha Rao visited Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, and later Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan (Sachdeva, 2016, p. 3; Szczepanski, 2019). In April 1995, India, Iran, and Turkmenistan signed a memorandum of understanding to build transport corridors for facilitating trade between each other. Most significantly, in 2000, India, Iran, and Russia signed the International North-South Trade Corridor (INSTC) agreement, which was ratified and came into effect in 2002. In 2012, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan agreed to extend their support to the INSTC. The Indian policymakers then pushed to expand and implement India’s Connect Central Asia policy in 2012, which was reinforced by incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to all these states between the 6th and 13th of July, 2015. Importantly, over the years, India not only maintained a privileged position in partnership with Russia in Eurasia but also signed strategic partnership agreements with Kazakhstan (2009), Uzbekistan (2011), Afghanistan (2011), and Tajikistan (2012). India’s participation in the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) since 2017 (the start of its official membership) is yet another dimension of its growing involvement in Eurasian politics (Sachdeva, 2016; Wani, 2020).

However, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the struggle for the balance of power in the region apparently arouse concern among Indian policymakers. India traditionally sees Eurasia as an area of strategic and economic engagement where it can emerge as an attractive market for some of its prominent partners, focusing, in particular, on Central Asia, the INSTC, and the Russian Far East. This paper studies the region collectively, in both historical and proactive perspectives; identifies factors that can promote dialogue to strengthen regional security and defense; looks into possible opportunities for cooperation in promoting India’s interests; and explores India’s developmental footprint in the Far East for further economic cooperation.

HISTORICAL CONNECTIONS AND GEOPOLITICS

Connectivity is a popular trend in international relations. The term ‘connectivity’ refers to “the physical, institutional and people-to-people linkages that comprise the foundational support and facilitative means to achieve political-security and the economic and socio-cultural pillars towards realizing the vision of an integrated community” (Yhome, 2015, p. 1218). Asian leaders have constantly sought to boost new ways of regional connectivity (Purushothaman and Unnikrishnan, 2019, p. 71). India has always been keen on maintaining connectivity underlined in the international Raisina Dialogue of 2016, in which the theme “Asia: Regional and Global Connectivity” focused specifically on Asia’s physical, economic, human, and digital connectivity. In 2017, Prime Minister Modi stressed the necessity to rebuild connectivity, saying: “Only by respecting the sovereignty of countries involved, can regional connectivity corridors fulfil their promise and avoid differences and discord” (ORF Raisina Dialogue, 2017).

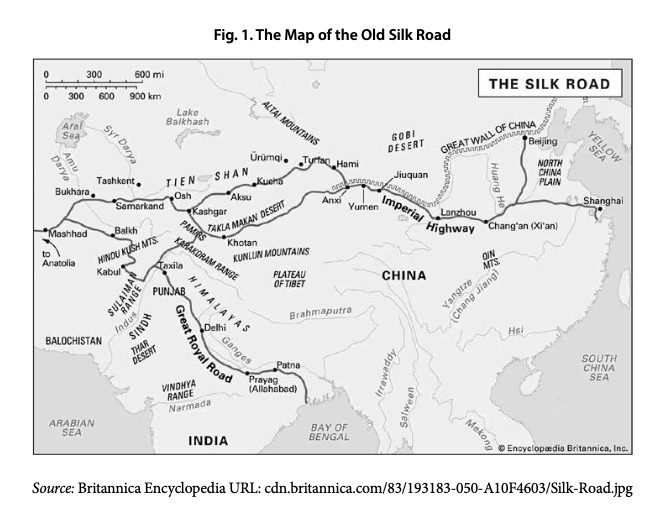

To understand India’s present-day interaction with Eurasia, it is worth looking at India’s connection with the Old Silk Road of the Mauryan times of about 2,400 years ago. Ancient Indian scholar Kautilya in Arthashastra coined the Sanskrit term ‘cinapatta’ to describe silk merchants’ travels from China (Sichuan) to India and the spread of Buddhism from India to China (Verghese, 2001). These routes expanded trade and interactions, with the northern route going through Chang’an (Xian) across the Gobi and around the Taklamakan Desert to Kashgar, Samarkand, Bokhara, Afghanistan, and Persia (Iran), and around the Caspian Sea to Europe. The southern route covered Sichuan, Yunnan, and northern Burma to reach India. The Silk Road was not a real road, as many would think, but a network of trade connections used by merchants to carry goods from the Eastern Mediterranean to Central Asia and from Central Asia to China. The Silk Road also used maritime routes as many goods reached Rome via the Mediterranean, and goods from Central Asia were brought to the Pacific.

The idea of reviving the Silk Road, or connecting a greater part of Eurasia is a mega cross-border project (UNESCO, 1997). Since 1990 the revival of the Silk Road has been discussed at all levels—by states and organizations, scholars of culture and business groups. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has got engaged in the initiative to revive the Silk Road by repairing the road connection to the Xinjiang Autonomous Region of China with Central Asia and Iran. The Europe-Caucasus-Asia corridor (TRACECA) is still referred to as the ancient great Silk Road (Gorshkov and Bagaturia 2001). The Asian Highway (AH) network, 141,000 kilometers long, crossing thirty-two Asian countries and linking them to Europe, is another mega project that since 1959 has been encouraging the revival of historical connections (Dulambazar, 2016, p. 42). The initial AH routes AH1 and AH2 aimed to link Bangkok with Tehran through Yangon, Dhaka, New Delhi, Rawalpindi, and Kabul, further connecting to Turkey and E-roads system in Europe (Dayal, 2010). The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), connecting India with Iran and linking other countries, places more emphasis on the idea of reviving the Silk Road (Ramachandran, 2019).

Later, the idea of the Silk Road connecting Eurasia transformed into China’s grand strategy that since 2013 has been referrred to as One Belt, One Road (OBOR). This 21st-century Silk Route economic belt is to connect China to Europe, the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean, while the Maritime Silk Route is designed to connect Asia with Europe and Africa. As China promoted OBOR together with aid, loans, and infrastructure development, it caused concern among neighboring states, such as India and Russia, and also in the U.S.

Russia’s attitude towards BRI is rather moderate, though. It sees itself as a partner rather than a competitor of China in the global primacy. In 2015, the Silk Road Fund (SRF), created by Beijing to finance the BRI projects, received a 9.9% share in Russia’s Yamal LNG project located north of the Arctic Circle. In 2018, the volume of bilateral trade between Russia and China exceeded $100 billion. Yet Moscow does not overly depend on China in terms of the market. Russia’s main objective in cooperating with China winin the BRI framework is to develop its economy, avoiding Beijing’s influence on Moscow’s policies (Yujun et al., 2019).

As for the U.S., it believes that BRI’s true goal goes far beyond economic gains. If successful, it will serve as a global trade hub and as a tool for projecting China’s military capabilities and its influence on the political decisions of the countries involved. So, the U.S. is clearly interested in pressurizing China and looks for alternative projects (Hillman and Sacks, 2021). Others see the Trans-Pacific Partnership as a way to create an economic territory hostile to China’s interests.

Many commentators viewed BRI as a response to Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” aimed at countering U.S. foreign policy initiatives by rebalancing its strategy. The New Silk Road Initiative (NSRI), announced in 2011 in Chennai by then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as promoting regional integration between Europe and East Asia, was perceived by China as a sign of encroahment on Afghanistan and Central Asian states. BRI’s focus is also directed at Central Asia but not at Asian maritime regions. At the initial stage, BRI’s key strategy was improving China’s energy and food security. BRI was also meant to resolve the so-called Malacca Dilemma. Considering China’s limited control over available sea routes that account for 80% of its energy imports and the growing geopolitical tension with India, China seeks to diversify its supply routes by investing in the pipelines in Central Asia to connect China with the Indian Ocean via the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). This is viewed as a solution to China’s blockade by the U.S.

The international community also sees BRI as threatening states’ sovereignty, exporting sub-standard norms and practices, and holding grave geostrategic implications. A major concern is the possibility of getting engaged in a “debt-trap” diplomacy, getting entrapped in economic dependency by developing countries, and falling under increased dependence on China’s geopolitical influence. The Center for Global Development names eight countries that are particularly at risk of debt distress resulting from the involvement in BRI, of which Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Malaysia are most vulnerable (Yujun et al., 2019). For instance, the Hambantota Port of Sri Lanka was acquired by China for ninety-nine years, forcing Colombo to give up control in return for a Chinese bailout. In Pakistan, the CPEC fueled opposition over its financial crisis. This debt-trap argument aroused concern when Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad canceled a $23 billion investment in BRI, warning that it was a new form of colonialism (Ibid). Thus, BRI, which came as the revival of the Old Silk Road, has been working as an economic project in China’s geopolitical interests.

GEOPOLITICS AND MACKINDER’S CONCEPTAS THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Since the Great Game, which started in 1830 as a rivalry between the British and the Russian Empires over trade routes, Central Asia has been a region of hostilities. Britain sought to control Central Asia mainly as a buffer zone and saw it as a crown jewel of its empire, while in Russia’s eyes it was a territory meant to expand its sphere of influence (Dave, 2016). Halford Mackinder, a British strategist, in his paper, The Geographical Pivot of History, read to the Royal Geographical Society in 1904, stated that the one “who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the world island; who rules the world island commands the world.”

According to Mackinder, the world includes the “World Island” and the “Outer Island.” The “World Island” comprises Africa, Europe, and Asia, while the “Outer Island” is America, British Isles, and Australia. The one who controls the World Island controls the world, producing population, weapons, and other resources. The World Island is also divided into two parts: the “Heartland” (inaccessible to a sea power) and the “Rimland” (the “inner crescent” consisting of Arabia, Western Europe, East Asia, and India) (Ismailov and Papava, 2010). There is no access to the sea or ocean for the Heartland states, and it has a flat landscape and arid climate that stimulates human migrations, wars, and trade. Remarkably, calling the flat Eurasian landscape the “Heartland,” Mackinder highlighted the region’s geopolitical and geo-strategic importance to global politics, and later Brzezinski (1997) called Central Asia “the global chessboard,” and some political analysts referred to it as the “New Great Game” (Cooley, 2012).

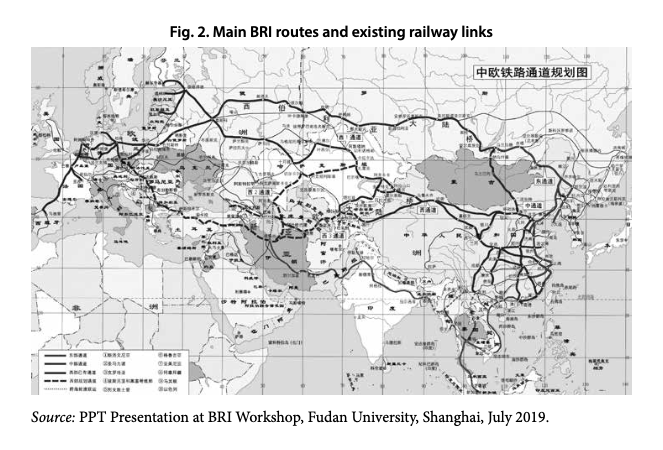

Deuck (2019) noted that China is located in both the Rimland and the northern part of the Heartland. Potentially, it could become a big player in the Heartland and may even rise to control most of it. Also, according to many analysts, China is seen as a major player in the “New Great Game” in Central Asia (Rehman, 2014; Chen and Fazilov, 2018). China is not only a land power but also an amphibious one, facing both land and sea. This means that China has opportunities to expand in both directions (Deuck, 2019). Thus, building the railways network and opening various corridors is crucial to China if one follows Mackinder’s concept of pivot to the Eurasian Heartland.

First announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping during his speech at the Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan in 2013 (MOFA, 2013), China’s BRI initiative aimed to revise the Silk Road with promises of international trade linkages like in the ancient world.

Fig. 2 shows the China-Europe Rail Road Plan with three major lines connecting China with other countries: the blue line indicates the east channel connecting China and Russia’s eastern regions; the green line indicates the middle channel that transcends Asia and Russia; and the red lines indicate the west channel connecting large parts of Europe with China.

This project serves China in the following ways: a) China capitalizes on its geopgraphical location within the Heartland; b) China gets the potential to rule the Heartland (as many scholars have predicted, see, for example, Rehman, 2014; Chen and Fazilov, 2018; Deuck, 2019); c) BRI challenges India’s strategic “Extended Neighborhood” initiative (“Connecting Central Asia Policy” developed in 2012), forcing India to look for alternatives.

At first, India’s attitude towards China’s seeking a connection to its neighbor was rather lukewarm, it was only after calls for BRI were projected across Asia (Purushothaman and Unnikrishnan, 2019, p. 75) that New Delhi got worried: it did not want Asia to be dominated by any country, and least so by China because of their animosities since the 1960s. And New Delhi got really outraged when the CPEC was included in BRI: India saw it as a violation of its sovereignty. In the BRI projects, part of the CPEC runs through Gilgit Baltistan (Pakistan-occupied part of Kashmir), which is entirely claimed by India. Another part runs through Kashmir, which India says Pakistan illegally ceded to China in the 1960s. When New Dehli was invited to participate in BRI, the official response from the Ministry of External Affairs read: “We are of the firm belief that connectivity initiatives must be based on universally recognized international norms, good governance, rule of law, openness, transparency, and equality…its projects must be pursued in a manner that respects the sovereignty and territorial integrity” (MEA, 2017).

India has three main concerns regarding BRI. The first one is that it involves South Asia, which means more of China’s influence in the region; the second one is its presence in the Indian Ocean; and the third one is BRI’s links to the Middle East. In other words, India is worried that China will become more powerful in South Asia while the Indian Ocean—not only its southern part but also the Arabian Sea—will face security problems. Thus, India’s refusal to take part in BRI is explained by purely geopolitical reasons.

Thus, if BRI serves China to regain the old and potentially potent idea of ‘Tianxia’ (China being the center of the world), that is, if it dominates the Heartland in Mackinder’s conceptual framework, it might eventually threaten China’s neighbor, India. Moreover, if China dominates the Heartland, it not only encircles India, but also commands the whole of Asia and the “World Island” in the long run.

INDIA AND CENTRAL ASIA

Before BRI was introduced in 2013, the “go west” policies and plans to connect Central Asia were first voiced in 2011 by then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton during her visit to India. While China took advantage of launching BRI before India took full initiative, India was considering the Central Asia region only within the “Extended Neighborhood Policy,” and it was only after meeting Clinton that Indian External Affairs Minister Somanahalli Krishna came up with a full-fledged “Connect Central Asia Policy” on June 12, 2012 in Washington (MEA, 2012).

Central Asian countries see India as the fastest growing economy, an influential actor in international politics, and an investor in the region (Agarwal and Sangita, 2017). On January 13, 2019, foreign ministers met at the India-Central Asia Dialogue in Samarkand (Uzbekistan) to strengthen cooperation between India and the Central Asian countries. The Central Asian countries welcomed India’s provision of $1 billion line of credit for development projects such as connectivity, energy, IT, healthcare, education, agriculture, etc. (Chaudhury 2020).

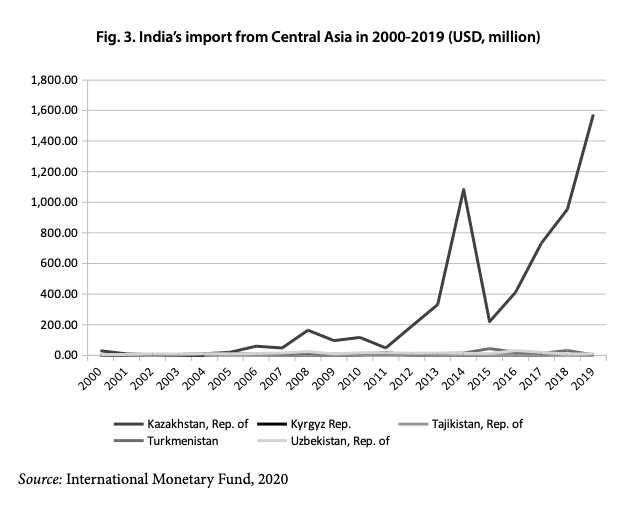

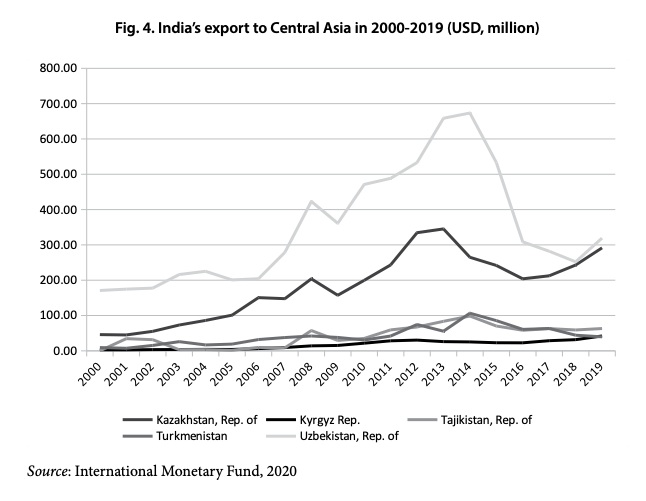

Fig. 4 shows that India’s trade increased significantly with Kazakhstan, as compared to other CIS countries. Its trade volume in Central Asia is less than a $1 billion. Kazakhstan and other “-stan” countries have oil and Kazakhstan has uranium, but it is easier for India to get oil from the Middle East because it is closer and there is no dedicated land route for transporting uranium from Central Asia as the demand is too small. Meanwhile, China is contiguous to these countries and so is Russia. Unfortunately for India, business with Russia is lopsided. Regions in eastern Russia get some key products from China while low-value products come there from the West because geographically Russia sits in between the two big industrial powers.

India’s enmity with Pakistan limits the transit of its goods to Afghanistan and Central Asia. Under the current conditions, in order to provide access to Afghanistan and Central Asia, India is intensively developing the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), the key link of which is Iran (Yakubov, 2020). In the INSTC agreement, Mumbai is chosen as the main port in India and Chabahar in Iran. In the long run, the INSTC aims to connect India with Iran, Russia, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Northern Europe.

INDIA AND THE INSTC

The INSTC was launched in 2000 as an agreement signed in St. Petersburg by Russia, India, and Iran, and later joined by other eleven Central Asian and Eurasian countries (Purushothaman and Unnikrishnan, 2019, p. 79). It foresees a 7,200 km multimodal trade corridor that runs from India to Russia and Europe, linking the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea. It uses a network of ships, trains, and road transport to ship goods. In 2014, the INSTC route was estimated to be 30% cheaper and 40% shorter and faster (Roy, 2015). In 2016, the lifting of international sanctions on Iran dramatically pushed the implementation of its project (Yakubov 2020). In 2018, the parties resumed talks on rejuvenating the INSTC, indicating greater regional connectivity. The cost of transportation now is $4,900 per TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit), and estimated to reach $3,400 per TEU with the new route (Jacob, 2020).

Apart from reducing the time and costs, the INSTC helps both India and Russia boost their bilateral trade, which is to reach $30 billion over the next ten years from $7 billion in 2016 (Singh and Sharma, 2017). In total, 69% of the railway infrastructure has been completed, with two of the three sextions of the Chabahar-Zahedan line launched recently. The 628 km rail project is expected to be completed in 2024. This connects the Chabahar port through the existing Iranian railway to Turkmenistan in the north, and to Afghanistan—from Zabol through the Zaranj-Delaram Highway, and from Khaf (South Khorasan Province) to Herat.

INDIA AND THE FAR EAST

Just like India, Russia, too, does not want any hegemony in this landmass of Eurasia on the part of China. The distance covered by the current route running through the Suez Canal to St. Petersburg is 10,000 nautical miles and India is looking for a separate maritime route that would connect it to the Russian Far East. India was the first country to establish a consulate in Vladivostok in 1992. In 2019, India was invited as the chief guest to the 5th summit of the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) held on September 4-6, 2020, in Vladivostok, where Modi pledged a $1 billion line of credit for the development of the region. India’s INSTC can connect the Russian Far East to the Indian Ocean. This corridor runs through Aktau in the Kazakh area of the Caspian Sea, and could be connected with the Trans-Siberian railway in the Omsk Region via a road and the railroad network. The opening of a sea route is likely to help the project.

Compared to the existing route from Mumbai to St. Petersburg, which is 8,675 nautical miles long, the proposed route from Chennai to Vladivostok will be only 5,647 nautical miles long, much shorter and faster. The route will run through Vladivostok to Chennai via the Sea of Japan (passing the Korean Peninsula), pass Taiwan and the Philippines (in the South China Sea), through the Strait of Malacca to the Bay of Bengal, and pass Andaman and Nicobar Islands to Chennai. This route is about 10,300 km long, and large ships will cover the distance in ten to twelve days, traveling at the normal cruising speed of 20-25 knots or 37-46 km/hour (The Times of India, 2019). This maritime corridor will not only allow India and Russia to establish economic links, but will also possibly connect Southeast Asia. Today, the Russian Far East is heavily dependent on East Asia, particularly China. Russia is aware of its neighbor’s presence and wants India to play a bigger role in counterbalancing China in the Far East.

A CRITICAL EVALUATION INDIA’S (RE)CONNECTION TO EURASIA

Mackinder’s Heartland is an area that was once ruled by the Russian Empire and was part of the Soviet Union. He argued that Central Asia had long been the geographical pivot of history and would remain pivotal to world politics. One of Mackinder’s key ideas is the importance of control over Eurasia. Mackinder emphasized that the geographical pivot of history would remain important even if Russia were to be subordinated to another power, such as China (IDSA, 2016). Many political analysts tend to limit Mackinder’s theory to geopolitical domination without giving due attention to its geoeconomic dimension.

As the analysis shows, India’s political interest in Eurasia and efforts to counterbalance China in the region do not match reality. There must be economic gains to sustain political reality. India’s approach towards Eurasia is based not on economic benefits but on a certain level of political hype. So, the debate around the feasibility of the Indian connectivity initiatives boils down to the premise that “everything depends on the markets.” This implies a set of questions to answer: What is India importing and what is India exporting? What will determine the connectivity in a free-market globalized world? Should we build a road where there is no business, and build a railway where there are no people to use it? (Guruswamy, 2020).

In terms of market principles, trade will be where there is supply and demand. India cannot compete with China even in the inner part of Central Asia, India’s manufacturing industry is weak and there are no profit margins. To find a market for international trade, economic freedom is needed (incidentally, the Old Silk Road was little controlled by the state (formally empire)). The Heritage Foundation relates economic freedom to four main factors that can be under government control (to a greater or lesser degree) and can influence the economic environment: 1) rule of law; 2) government size; 3) regulatory effectiveness; 4) the degree of market openness (Gulaliyev et al., 2017).

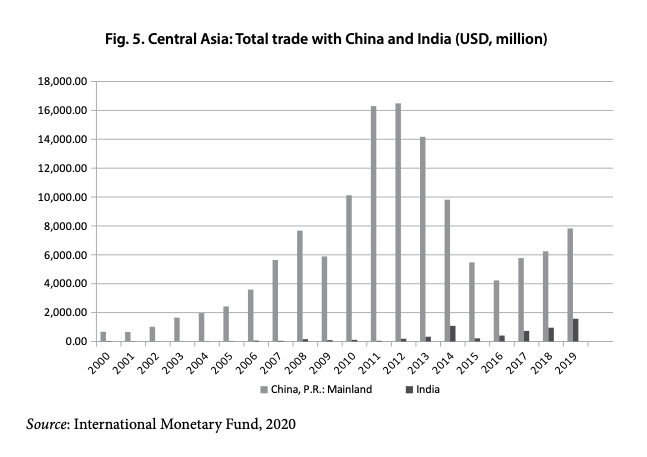

Fig. 5 shows that China leads in trade with Central Asia as compared to India. It was only in the recent years that India gained access to Central Asia, but still falls behind China in this respect. Thus, India’s market must be, first of all, competitive and collaborative with China. India is not able to compete with China in Central Asia for the mere reason that China directly adjoins Central Asia. China is interested in a railroad network to export goods to Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. It will also connect it to Russia, which is the major trade partner of China.

Where does India fit in the current marketplace? In the old days, India had a political reason: the Soviet Union was there, and India had established trade with the USSR which imported lots of goods like coffee, tea, spices, textiles and tobacco from India. Unfortunately, that cash-lucrative market is gone.

Unlike India, China’s position is very different: it has got reserves of $3 trillion, and it has to invest this money somewhere in order not to have it devalued. China has devised a new method: it gives the BRI money in loans to the “-stan” countries like Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, so that they could buy Chinese goods with those loans—cement, steel, equipment. And then these countries have to repay the Chinese loans. Of course, China does not give anything for free; it gives everything at a high rate of interest. It has been lending money to Pakistan at 5%, which is higher than the World Bank’s and IMF’s rates (Naviwala, 2017). As Mohan Guruswamy (2020) says, China assumes debt and transfers the cost to somebody else.

The Central Asian governments expect that the BRI investments in the infrastructure projects will help open the landlocked region economically and attract more global projects. In terms of BRI, two out of six corridors run through the Central Asian region, connecting China to Europe and to Iran and West Asia. China also offers the closest port to most of the Central Asian countries. Another factor is that no country can offer as big investments as those provided by China through BRI (Taliga, 2021, p. 6-7).

However, the BRI projects also arouse the “Chinese threat” sentiments among the people in Central Asia (Nurgozhayeva, 2020). Like in the case of Pakistan and Sri Lanka, the Central Asian countries run the risk of falling into a debt trap. China accounts for 16% of Kazakhstan’s total trade and its external debt to China stands at $12.3 billion. China became Kyrgyzstan’s creditor in 2012: out of $3.7 billion of external debt, $1.4 billion was issued by the Export-Import Bank of China. Kyrgyzstan, too, runs the risk of getting into the Chinese debt trap by agreeing to participate in BRI. As for Tajikistan, in 2015, $238 million, or 81.2% of the total FDI, came from China. Deeper cooperation within BRI will also pose the risk of a debt trap for Tajikistan (Vakulchuk and Overland, 2019).

According to the IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics, India’s total trade with Central Asia has grown from $108 million in 2000 to $1.5 billion in 2017. By comparison, from 2000 to 2017, Central Asia’s trade with China grew from $1.8 billion to $36.3 billion, largely due to an increase in oil and gas exports through Central Asia-China Gas Pipelines (CAGP) and Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline (The Economist, 2019). This indicates that building roads and railways is not sufficient for extending trade; it is important to build markets.

Although the South Caucasus is unsettled right now, Indian businesses are not afraid to invest in it. With both Central Asian and the South Caucasian regions, India’s annual trade stands at $2 billion (Sachdeva, 2016, p. 18). However, unlike Central Asia, the South Caucasus has not yet become an eye-catching target for the Indian policymakers.

So far China has been the primary trading partner in the Russian Far East, and Indian companies still have to face many challenges to be established in this region. Any foreign investor to do business in the Russian Far East would accept numerous high risks, such as “Western sanctions, poor infrastructure, and frequent changes in Russian legislation” (Simes, 2021). Indian companies also face competitor China’s rivals that benefit from lower transportation costs. There is a huge difference between transporting timber from the Far East to China and transporting it to India. This makes it more expensive for India to buy natural resources from the region.

Yet India can find advantages where Beijing disputes. China’s recent decision to restrict seafood imports from the Russian Far East gives India a business opportunity. These little economic linkages will become political linkages and the West fears this the most. Thus, Eurasia needs a revision of old players in the region.

India and China are destined to become big economic partners. Demographically, India is now in a situation where China was thirty years ago. India’s middle class is expanding and needs consumer goods, such as cars, refrigerators, computers, washing machines, and mobile phones. China is the second biggest automobile market in the world. China contributes 30% to the world GDP growth, India contributes about 9% and this is a big growing market. If China is to benefit from exporting to India, it must invest in India and sell in India, that is, avail of an opportunity to make profit, not to get windfall gains.

The cornerstone of Erasia will be Russia, India, and China; after all the SCO or BRICS is impotent without Russia, China, and India. Moscow, which has remained silent for quite some time, must take the lead. By 2040, Russia and India will predictably account for 30% to 35% of world GDP, respectively. PWC (2015) forecasts that India alone has the potential to become the second largest economy in the world by 2050. Russia, with its technology and good intellectual manpower, is crucial for the global economy. Indian, Chinese, and Russian leaders must think more of Eurasia in strategic terms.

* * *

India is historically embedded in Eurasia: in ancient times it was broadly engaged in Eurasian connections through the Silk Road and today through the Indian government’s efforts to maintain cooperation with Central Asian countries in economic, trade, and science and technology fields. Historical ties must not be neglected, and finding any linkages will be helpful for the future development of India and entire Eurasia likewise. India’s geographical position and its pivot to Eurasia remain highly appealing. To improve economic cooperation with Eurasian countries, India should continue its search for new innovative ways and work for multidimensional relationships. Reviving the Silk Road connectivity and focusing on the development of the transport corridor can secure the country’s economic and trade development.

Economic connections are the root of political connections and of a geo-strategy where economic gains are not the key goal. Transport corridors may provide a platform for improving cooperation and communication as indispensible conditions for multilateral relations. This will facilitate regional cooperation and help shape a new geopolitical and security envrionment.

Agarwal, P. and Sangita, S., 2017. Trade Potential between India and Central Asia. Margin-The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 11(4), pp. 418-448.

Brzezinski, Z., 1997. A Geo-Strategy for Eurasia. Foreign Affairs, 76(5), Sep.-Oct., pp. 50-64.

Chaudhury, D. R., 2020. India Extends $ 1 billion Line of Credit to Central Asia for Connectivity & Other Development Projects. The Economic Times, 28 October. Available at: economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/india-extends-1-billion-line-of-credit-to-central-asia-for-connectivity-other-development-projects/articleshow/78917598.cms?from=mdr [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Chen, X. and Fazilov, F., 2018. Re-Centering Central Asia: China’s “New Great Game” in the Old Eurasian Heartland. Palgrave Communications, Vol. 4, p. 71.

Cooley. A., 2012. Great Games, Local Rules: The New Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford University Press, pp. 120-122.

Dave, B., 2016. Resetting India’s Engagement in Central Asia: From Symbols to Substance. Policy Report, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Available at: www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/PR160202_Resetting-Indias-Engagment.pdf [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Dayal, R., 2010. Asian Highway Has a Long Way to Go. The Economic Times, 4 December. Available at: economictimes.indiatimes.com/opinion/et-commentary/asian-highway-has-a-long-way-to-go/articleshow/7039739.cms?from=mdr [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Dueck, C., 2019. Mackinder’s Nightmare: Part Two. National Security Program, 9 October [online]. Available at: www.fpri.org/article/2019/10/mackinders-nightmare-part-two/ [Accessed 23 January 2021].

Dulambazar, T., 2016. Physical Connectivity between Asia and Europe: A Mongolian Perspective. In: Asia–Europe Connectivity Vision 2025 Challenges and Opportunities An ERIA–Government of Mongolia. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia. Available at: www.eria.org/Asia_Europe_Connectivity_Vision_2025.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2020].

Gorshkov, T. and Bagaturia, G., 2001. TRACECA – Restoration of Silk Route. Japan Railway & Transport Review, 28 September. Available at: www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr28/pdf/f50_gor.pdf [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Gulaliyev et. al., 2017. Assessment of Impacts of the State Intervention in Foreign Trade on Economic Growth. Espacios, 38(47), p. 33. Available at: www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n47/a17v38n47p33.pdf [Accessed 11 January 2021].

Guruswamy, M., 2020. Interview (Skype), 29 December.

Hillman, J. and Sacks, D., 2021. China’s Belt and Road: Implications for the United States. Council on Foreign Relations, Independent Task Force Report No. 79. Available at: www.cfr.org/report/chinas-belt-and-road-implications-for-the-united-states/ [Accessed 20 September 2021].

IDSA, 2016. Chaitanya Nagalla Asked: How Relevant Is Mackinder’s ‘Heartland Theory’ in the Contemporary Geo-Politics? IDSA, 27 July. Available at: idsa.in/askanexpert/mackinder-heartland-theory-in-the-contemporary-geo-politics [Accessed 20 March 2021].

Ismailov, E. and Papava, V., 2010. Rethinking Central Asia. Monograph. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Silk Road Studies Program, Washington. D.C. Available at: www.silkroadstudies.org/resources/pdf/Monographs/1006Rethinking-4.pdf [Accessed 20 March 2021].

Jacob, S., 2020. Concor to Take INSTC Route for Russia to Save Transit Time and Cash. Business Standard, 26 February. Available at: www.business-standard.com/article/companies/concor-to-take-instc-route-for-russia-to-save-transit-time-and-cash-120022601642_1.html [Accessed 12 March 2020].

Kundu, Nivedita D., 2016. India’s Emerging Partnerships in Eurasia: Strategies of New Regionalism. New Delhi: Vij Books India Pvt. Ltd.

MEA, 2012. Keynote Address by MOS Shri E. Ahamed at First India-Central Asia Dialogue. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 12 June [online]. Available at: www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/19791/ [Accessed 20 March 2021].

MEA, 2017. Official Spokesperson’s response to a query on participation of India in OBOR/BRI Forum. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. [online]. Available at: mea.gov.in/media-briefings.htm?dtl/28463/Official+Spokespersons+response+to+a+query+on+participation+of+India+in+OBORBRI+Forum [Accessed 20 March 2021].

MOFA, 2013. President Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech and Proposes to Build a Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries. MOFA of the People’s Republic of China [online]. Available at: www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpfwzysiesgjtfhshzzfh_665686/t1076334.shtml [Accessed 20 March 2021].

Naviwala, N., 2017. Pakistan’s $100B Deal with China: What Does It Amount To? Devex, 24 August [online]. Available at: www.devex.com/news/pakistan-s-100b-deal-with-china-what-does-it-amount-to-90872 [Accessed 1 January 2021].

Nurgozhayeva, R., 2020. How Is China’s Belt and Road Changing Central Asia? The Diplomat, 9 July. Available at: thediplomat.com/2020/07/how-is-chinas-belt-and-road-changing-central-asia/ [Accessed 17 June 2021].

ORF Raisina Dialogue, 2017. Available at: orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Raisina_Report_2017-WEB.pdf [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Purushothaman, U. and Nandan Unnikrishnan, 2019. A Tale of Many Roads: India’s Approach to Connectivity Projects in Eurasia. Indian Quarterly, 75(1), pp. 69-86.

PWC, 2015. The World in 2050: Will the Shift in Global Economic Power Continue? PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, February [online]. Available at: www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/the-economy/assets/world-in-2050-february-2015.pdf [Accessed 1 January 2021].

Ramachandran, S., 2019. India Doubles Down on Chabahar Gambit. The Diplomat, 14 January. Available at: thediplomat.com/2019/01/india-doubles-down-on-chabahar-gambit/ [Accessed 20 March 2021].

Rehman, Khalil ur, 2014. The New Great Game: A Strategic Analysis. The Dialogue, Vol. IX(1). Available at: www.qurtuba.edu.pk/thedialogue/The%20Dialogue/9_1/Dialogue_January_March2014_1-26.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2020].

Roy, M. Singh, 2015. International North-South Transport Corridor: Re-Energising India’s Gateway to Eurasia. IDSA [online]. Available at: idsa.in/issuebrief/InternationalNorthSouthTransportCorridor_msroy_180815 [Accessed 1 January 2021].

Sachdeva, G., 2016. India in a Reconnecting Eurasia: Foreign Economic and Security Interests. Center for Strategic & International Studies. Available at: csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/160428_Sachdeva_IndiaReconnectingEurasia_Web.pdf [Accessed 20 March 2021].

Sazanov, Kuanysh-Beck, 2008. The Grand Chatrang Game. AuthorHouseUk.

Scott, D., 2009. India’s “Extended Neighborhood” Concept: Power Projection for a Rising Power. India Review, 8(2), pp. 107-143.

Simes Jr., D., 2021. India Seeks Economic Energy in Russian Far East, Countering China. NIKKEI Asia, 22 February. Available at: asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/India-seeks-economic-energy-in-Russian-Far-East-countering-China [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Singh, S. and Sharma, M., 2017. INSTC: India-Russia’s Trade to Get a Major Boost. Russian International Affairs Council, 10 September. Available at: russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/instc-india-russia-s-trade-to-get-a-major-boost/ [Accessed 14 November 2020].

Smith, Dianne L., 1996. Central Asia: A New Great Game? Available at: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/109548/Central_Asia_New_Great.pdf/

Szczepanski, K., 2019. What Was the Great Game? Thought co. Available at: www.thoughtco.com/what-was-the-great-game-195341 [Accessed 20 March 2021].

Taliga, H., 2021. Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia. ITUC and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Belgium. Available at: www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/belt_and_road_initiative_in_central_asia.pdf [Accessed 17 June 2021].

The Economist, 2019. At the Periphery: India in Central Asia. The Economist, 4 January. Available at: country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=747505258&Country=India&topic=Politics&subtopic=Forecast&subsubtopic=International+relations&oid=1437529527&aid=1 [Accessed 17 June 2021].

The Indian Express, 2019. Explained: The Sea Route from Chennai to Vladivostok. The Indian Express, 6 September. Available at: indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-the-sea-route-from-chennai-to-vladivostok-5969578/ [Accessed 20 November 2020].

UNESCO, 1997. The Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue. Paris.

Vakulchuk, R. and Overland, I., 2019. China’s Belt and Road Initiative through the Lens of Central Asia. In: Fanny M. Cheung and Ying-yi Hong (eds.) Regional Connection under the Belt and Road Initiative: The Prospects for Economic and Financial Cooperation. London and New York: Routledge.

Verghese, B. G., 2001. Reorienting India: The New Geo-Politics of Asia. New Delhi: Konark Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Wani, A., 2020. India and China in Central Asia: Understanding the New Rivalry in the Heart of Eurasia. ORF Occasional Paper, 235, February, Observer Research Foundation. Available at: www.orfonline.org/research/india-and-china-in-central-asia-understanding-the-new-rivalry-in-the-heart-of-eurasia-61473/ [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Yakubov, I., 2020. India and Central Asia: The Thorny Path of Cooperation. Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting. The Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Available at: cabar.asia/en/india-and-central-asia-the-thorny-path-of-cooperation#_ftn2 [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Yhome, K., 2015. The Burma Roads: India’s Search for Connectivity through Myanmar. Asian Survey, 55(6), pp. 1217-1240.

Yujun, F. et al., 2019. The Belt and Road Initiative: Views from Washington, Moscow and Beijing. Carnegie-Tsinghua, Center for Global Policy, 8 April. Available at: carnegietsinghua.org/2019/04/08/belt-and-road-initiative-views-from-washington-moscow-and-beijing-pub-78774 [Accessed 17 June 2021].