Both views are incorrect. In the case of Ukraine—the most important of all expansion-targets—the U.S.’s pursuit of NATO expansion began almost immediately after Ukrainian independence, at a time when Russia was both friendly and weak. (If anything, that lack of desire or ability to stop NATO expansion was a crucial condition permitting expansion. Once that condition disappeared, expansion violently came to a (partial) halt.)

This article reveals that the U.S.:

• by 14 October 1994, had adopted the objective of Ukrainian accession to NATO (Section 1);

• by 2001, began taking concrete action to achieve this (2);

• initially sought a Membership Action Plan (MAP) for Ukraine in 2006, and accession in April 2008 (3);

• actually came close in 2008 to winning a MAP in 2010 (4); and

• has subsequently continued to desire and work towards accession (5), with some de facto success (6).

For citation, please use:

Royce, D.P., 2024. The U.S.’s Pursuit of NATO Expansion into Ukraine Since 1994. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(3), pp. 46–70. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-3-46-70

U.S. desire/intent to admit Ukraine

The earliest indication of U.S. support for Ukraine’s membership is perhaps Yuri Kostenko’s claim that, on 7 December 1992 (when Kostenko was Ukraine’s Minister of Environmental Protection and Nuclear Safety), Frank Wisner, U.S. Under Secretary of State for International Security Affairs, “requested a meeting with Ukraine’s Ambassador in Washington, Oleg Bilorus, in which he [Wisner] seemed to have urged Ukraine to join NATO.” Kostenko bases this on a record of the conversation in his personal possession, sent by Ukraine’s Deputy FM to the Speaker of its Parliament on 21 December 1992 (Kostenko, 2021, pp. 140, 319).. However, it is not clear precisely what Wisner said, and whatever he did say may have been a not-necessarily-honest part of the U.S.’s effort to convince Ukraine to relinquish the nuclear weapons on its territory. But NATO membership does seem to have been genuinely considered within the USG as a means of resolving the nuclear issue: e.g., in May 1993, U.S. National Security Advisor Anthony Lake suggested that “if we admitted Ukraine to NATO, the nuclear question would of course resolve itself” (Sarotte, 2021, p. 160).

In any case, the U.S. was soon favorably considering Ukrainian NATO membership—unambiguously, and independently from the nuclear issue. For instance, a 7 September 1993 paper, from the DoS Policy Planning Staff, proposed admitting Ukraine (alongside Belarus and Russia) into NATO in 2005.[1]

And Ukrainian admission was essentially made U.S. policy—seemingly without much debate or any real opposition—by an NSC working paper dated 12 October 1994 and titled Moving Toward NATO Expansion. The document came to serve as the “blueprint” or “roadmap” for U.S. expansion policy in the coming years (Vershbow, 2019, pp. 430, 432), and held that the “possibility of NATO membership for Ukraine and Baltic states should be maintained; we should not consign them to a gray zone or a Russian sphere of influence.” It recommended that NATO “keep the membership door open” for them (and Romania and Bulgaria) (Lake, 1994). In contrast, the paper essentially foreclosed the possibility of Russian membership, which had been discussed in some earlier, lower-level documents. It held that the “possibility of membership in the long term for a democratic Russia should not be ruled out explicitly” [emphasis added]. NATO should produce a “statement of new, more ambitious goals for [an] expanded NATO relationship with Russia in addition to PFP (implicitly foreshadowing [an] ‘alliance with the Alliance’ as an alternative [for Russia] to [the] membership track).”

On 14 October 1994, President Clinton not only checkmarked the paper and wrote “looks good” on its front page, but also made two other markings on the document—one of them, a pair of parallel lines emphasizing the stipulation to keep the “membership door open” for Ukraine (and the others) (Lake, 1994).

NSC Eurasia Director Nick Burns subsequently asked that Deputy State Secretary Strobe Talbott “please note, in particular, the emphasis [on] trying to figure out how to deal with Ukraine and the Baltics,” as Burns and Anthony Lake believed that “while they may not be the prime early candidates for NATO,” “we ought to concentrate ourselves intellectually on them as we continue developing our NATO policy.”[2]

In accordance with this new policy, on 18 January 1996, Talbott told the Ukrainian Ambassador that “the U.S. is determined that the enlargement process will continue and that the ‘first new members will not be the last.’ The U.S. is very specifically concerned about Ukraine.”[3] On 25 March 1996, Talbott assured the Estonians that “until we can better answer the question of Baltic and Ukrainian security, the rationale for NATO enlargement will not be complete [i.e. satisfied].”[4] In September 1996, Talbott told the Chairman of Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council that: “…the [NATO-Ukraine] relationship must include [the] possibility that Ukraine might at some future date decide to join NATO. …Russia wants it understood that the Baltic states and Ukraine could never be allowed to join NATO. …the U.S. has made it very clear that such a position is unacceptable. …NATO’s door must be open and never exclude the Baltic states, Ukraine[,] or any other democratic country.”[5]

And on 13 June 1997, Talbott told the Ukrainian Ambassador that “…possible Ukrainian membership is not just a theoretical notion, but rather ‘a guiding principle which we have restated over and over. It is an article of faith’ for the U.S. … The U.S. will never ‘pressure’ Ukraine to seek NATO membership…but NATO’s door will remain open in the future to a democratic, reformist Ukraine.”[6]

In fact, Talbott on 13 June 1997 was responding to Ukraine’s Ambassador and Deputy Chief of Mission telling him that Ukraine might apply for membership “early” in the coming century.[7] And this was far from the first such expression of Ukrainian intent. Already by October 1993, Assistant Secretary of State Robert Gallucci was writing that “Ukraine … has repeatedly expressed an interest in joining NATO.”[8] Ukrainian Deputy FM Boris Tarasyuk told U.S. officials, in February 1995, that “no matter what we say publicly, I can tell you that we absolutely want to join NATO” (Asmus, 2002, p. 339). Tarasyuk similarly told Talbott, in January 1996: “As for Ukraine and [NATO] enlargement, at this moment neither NATO nor Ukraine is willing to express publicly what they have in mind, although the U.S. of course is aware of Ukraine’s expectations.”[9]

Thus, other less-committal Ukrainian statements about membership[10] likely indicate not an actual lack of desire, but rather a recognition that public pursuit of membership was currently inopportune. And in February 2002, Ukraine did publicly target membership, when President Kuchma inserted the following into the State Program of Ukrainian Cooperation with NATO for 2001-2004: “Ukraine’s current approach to the development of a security policy is based upon the state’s unchanging strategic objective of full-scale integration into European and Euro-Atlantic structures and of fully-fledged participation in the pan-European security system (President of Ukraine, 2002).

Any ambiguity produced by this somewhat euphemistic language was eliminated on 23 May 2002, when Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council adopted the decision to pursue NATO membership, and on 9 July 2002, when Kuchma issued a decree to the same effect (RIA Novosti, 2002). And this objective was actively pursued: for instance, as reported by U.S. Embassy Ankara, in a 1-2 December 2003 visit to Turkey, PM Yanukovich “requested [Turkish] support for Ukraine’s [acquisition of a] membership action plan.”[11]

But, to return to the matter of U.S. preferences, they were also made clear to Russia. On 15 July 1996, Talbott warned Russian FM Yevgeny Primakov that “if … you’re not prepared to accept the Baltic states’ and Ukraine’s eligibility for NATO membership in the future, then we’ve got a collision of red lines.”[12] In fact, a July 1996 internal DoS paper identified one of Russia’s goals, in negotiations on the NATO-Russia charter, as “rul[ing] out Baltic and Ukrainian membership in NATO,” and it stipulated a U.S. effort to persuade the Russians “that realism means [i.e. requires] abandoning or significantly modifying their coming-in goals.”[13] And when Clinton and Yeltsin met in Helsinki in March 1997, Yeltsin tried to exchange Russian acquiescence to limited NATO expansion for an “oral agreement” between the two presidents that NATO would keep out of former Soviet states. Per Talbott, Clinton “…did not just say ‘no’ to Russian opposition to eventual Baltic or Ukrainian membership in NATO; he explained why ‘no’ is the only right answer, even from the Russian point of view.”[14]

At about the same time, U.S. support for Ukraine’s NATO membership was also enshrined into law by the NATO Enlargement Facilitation Act—passed 353-65 in the House[15] and 81-16 in the Senate[16] and enacted on 30 September 1996[17]—which in part read: “…in order to promote economic stability and security in Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Moldova, and Ukraine: “(1) the United States should continue and expand its support for the full and active participation of these countries in activities appropriate for qualifying for NATO membership; … (4) the process of enlarging NATO to include emerging democracies in Central and Eastern Europe should not be limited to consideration of admitting Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia as full members of the NATO Alliance” [emphasis added].

U.S. actions to realize Ukrainian accession

A few years later (at most), the U.S. began providing material/financial support to certain ‘non-governmental’ organizations in order to improve Ukrainian public opinion regarding membership. (The U.S. would subsequently identify public opinion as “the Achilles Heel of Ukraine’s ambitions to be invited sooner (in 2008) rather than later to join NATO,” and repeatedly exhorted the Ukrainian government to invest more of its own resources into a pro-NATO “public education campaign.”[18] In fact, NATO accession never achieved majority support in Ukraine’s southeastern region before much of that territory was lost by Ukraine, and opinion polls became unreliable for obvious reasons, beginning in 2022.[19])

Although U.S. activity in this sphere may very well have begun earlier, the first for which I have evidence started in late 2001 (the beginning of U.S. Fiscal Year 2002), when the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) began supporting the Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation (IEAC),[20] founded that year “to promote the idea of European and Euro-Atlantic integration within Ukrainian society” (Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation, 2002). Support for the IEAC, which continued through 2009, amounted to $477,341 (current USD) from NED alone, and paid for things like “Euro-Atlantic clubs” (FY2002), “NGO networking and public meetings intended to build support for greater integration of Ukraine into Western political and economic structures” (FY2005), and “public hearings … on Ukraine’s integration into the EU and … NATO” that targeted southeastern regions “where polls have shown low public support for integration” (FY2006).

Then—just after Ukraine officially adopted the goal of NATO membership, as noted above, in early-mid-2002—the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan was concluded, on 22 November 2002.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) described it as “modeled on NATO’s Membership Action Plan,” featuring Ukrainian commitments to various reforms, and noted that “U.S. officials have said that, if Ukraine takes real strides towards reform, and meets the qualifications for NATO membership, it should have the opportunity to join the Alliance” (CRS, 2004). Indeed, the Plan clearly identified accession as the end-goal of reforms, acknowledging “Ukraine’s foreign policy orientation towards European and Euro-Atlantic integration, including its stated long-term goal of NATO membership,” and stating that “reform efforts and military cooperation also support Ukraine’s strategic goal of Euro-Atlantic integration by gradually adopting NATO standards and practices, and enhancing interoperability between the armed forces of Ukraine and NATO forces.”

More concretely, the Action Plan stipulated 13 areas of Ukrainian cooperation with NATO, including: general defense reform (#1, 2, 5); achieving “full interoperability” of forces (#4, 8, 12); creating a NATO-compatible Rapid Reaction Force (#7); joint operations (#3, 6); and technological-scientific cooperation (#13).[21] Notably, the Action Plan was concluded mere months after Ukraine officially/publicly declared the goal of NATO membership, indicating that the limiting factor had been on the Ukrainian side, as the U.S. and NATO were willing and eager to move ahead just as soon as Ukraine was.

U.S. pursuit of an intensified dialogue, MAP, and membership invitation for Ukraine in 2005, 2006, and 2008

23 January 2005 saw another leap forward in Kiev’s willingness/ability to join NATO, with Viktor Yushchenko’s inauguration as President.

Kuchma had also sought NATO membership, and even Yanukovich worked towards it as PM in 2002-2004. Indeed, U.S. officials saw Yanukovich and his party as much less hostile to NATO in private than they were in public[22]—at least until they “abandoned their previous insider support of NATO membership for a public anti-NATO line” in 2007.[23] Nevertheless, the Orange Revolution empowered forces whose support for membership was far more ardent and public, and the U.S. seized the opportunity to advance Ukrainian membership.

At the 22 February 2005 NATO Summit, merely one month since the Orange Revolution, President Bush welcomed Yushchenko and “reminded him that NATO is a performance-based organization and that the door is open, but it’s up to President Yushchenko and his Government and the people of Ukraine to adapt the institutions of a democratic state. And NATO wants to help, and we pledged help” (Bush, 2005).

The U.S. went on to repeatedly express support for Ukrainian membership, for example, telling the Ukrainians on 24 January 2006 that it “strongly supported Ukrainian aspirations for membership”;[24] telling the Bulgarians[25] and Romanians[26] in March 2006 that it sought to integrate Ukraine (and Georgia) into “Euro-Atlantic structures” and specifically NATO; and telling the French on 3 November 2006 that “U.S. intentions are to protect and promote Ukraine’s long-term prospects for NATO membership and to educate Ukrainians about the positive aspects of eventual accession.”[27]

Specifically, the U.S. sought to get Ukraine an Intensified Dialogue with NATO in April 2005, a MAP at some point in 2006, and an invitation to membership in April 2008.

The first step was soon accomplished. On 4 April 2005, Presidents Bush and Yushchenko issued a joint statement: “The United States supports Ukraine’s NATO aspirations and is prepared to help Ukraine achieve its goals by providing assistance with challenging reforms. The United States supports an offer of an Intensified Dialogue on membership issues … in Vilnius, Lithuania, later this month” (Bush and Yushchenko, 2005).

And, indeed, at that meeting in Vilnius on 21 April 2005, “NATO invited Ukraine to begin an ‘Intensified Dialogue’ on Ukraine’s aspirations to membership and relevant reforms.” NATO also agreed to “enhance public diplomacy efforts in order to improve understanding of NATO in Ukraine”[28] (which, as noted above, the U.S. had already been doing for some time).

Then, by September 2005 at the latest, the U.S. was planning a 2008 “enlargement summit”[29] that—given the “warnings” and “reservations” expressed by the French[30] and the Dutch[31] about admitting Ukraine at the event—was evidently intended to do just that. And an invitation in April 2008 would require a MAP by the end of 2006.

Ukraine hoped to get one a bit earlier: a 15 February 2006 cable from Embassy Kiev refers to “Ukrainian hopes to secure approval for a … MAP in the spring-summer of 2006”[32] and, on 19 April 2006, Ukraine’s Deputy FM told the U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor that “a positive signal to Ukraine on MAP[,] at the April 27-28 Sofia NATO Ministerial[,] would help Ukraine in its domestic debate on NATO.”[33]

However, in early March, the U.S. advised Ukraine against pursuing a “MAP decision in Sofia,” saying that “NATO allies had already decided not to make any decision on enlargement in Sofia” and that Ukraine should “be patient and wait until the Defense Ministerial in June, which would still permit Ukraine to have two full MAP cycles (which start in September) before NATO’s enlargement summit in 2008.”[34]

And following Ukraine’s 26 March 2006 elections, the U.S. switched its target to the November NATO Summit in Riga. On 19 April 2006, Deputy National Security Advisor Jack Crouch told Kiev that “tangible, visible efforts and results were needed to spur momentum” for Ukraine’s MAP effort, and “the U.S. was ready to help”—but, “as the U.S. engaged allies” on the matter, the new Ukrainian Cabinet needed to itself “state clearly that MAP and membership were definite goals.”[35] And the U.S. did engage its allies: on 18-19 May 2006, Ambassador to NATO Victoria Nuland presented to the German Foreign Ministry “the strategic rationale behind our Riga summit initiatives” but found the Germans “skeptical about near-term prospects for Ukraine moving to a NATO…MAP.”[36] In June 2006, the CRS noted that Kiev wanted “to join NATO as early as 2008,” that “NATO may consider whether to grant Ukraine a MAP at its November 2006 summit in Riga,” and that “U.S officials are backing Ukraine’s request to join the Alliance’s [MAP] program” (Woehrel, 2006a). On 22 June 2006, David Kramer, Deputy National Security Advisor for Europe, announced that “the United States is actively engaged at NATO to help Ukraine achieve its NATO goals, including…the Membership Action Plan that Ukraine is interested in. … Without a doubt, the United States sees Ukraine’s future as an integrated member of all Euro-Atlantic institutions” (Kramer, 2006).

Finally, an 11 August 2006 cable from Embassy Kiev referred to Ukraine’s “drive towards NATO via a … MAP” as a “key progra[m] launched by Yushchenko … which the U.S. closely cooperates [with, and which it] supports.”[37]

But much of this evidence for U.S. support also alluded to potential obstacles. Nuland encountered skepticism from certain NATO allies, while Crouch and Kramer worried that Ukraine’s indecision would deepen that skepticism. Kramer and the CRS noted that the Rada had rejected NATO overflight to Afghanistan, that a U.S. warship’s visit to Crimea had provoked protests and scandal, and that Ukraine’s “new parliament could have a majority opposed to NATO membership” (Woehrel, 2006a).

Kramer had earlier warned the Ukrainians that “MAP would be difficult if Ukraine did not have a government in place by July,” and on 31 July 2006, he told them that a letter from (soon-to-be PM) Yanukovich to NATO’s Secretary-General “reiterating Ukraine’s desire for MAP at Riga” would be helpful but “not enough.” In order to improve their “currently slim chances of a MAP invitation,” the Ukrainians should also pass a “long-stalled bill authorizing foreign exercises in Ukraine,” ratify “the 2004 NATO-Ukraine [memorandum of understanding] on strategic airlift,” send Yanukovich to make Ukraine’s case in Brussels, and send other officials to make its case in other NATO capitals.[38]

In reality, despite repeated promises from Yushchenko of an imminent request by Yanukovich for a MAP,[39] and obfuscation from Yanukovich himself,[40] no request ever came. In fact, in September 2006, Yanukovich outright said that Ukraine was “not ready” for a MAP, a position fiercely attacked by Yushchenko and the Orange-holdover ministers of foreign affairs and defense.[41] In essence, opponents of NATO membership—or, at least, political forces that wished to appear as though they opposed NATO membership—had acquired sufficient power to immobilize Ukraine’s post-Orange-Revolution movement towards MAP and membership (Woehrel, 2006b).

Consequently, Ukraine would not receive a MAP in Riga. Even the U.S. recognized, as Daniel Fried, Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, told Yanukovich on 7 September 2006, that it would “be better if Ukraine entered more slowly but based on a solid national consensus, rather than quickly but divisively.”[42] This meant not that the U.S. was giving up on Ukrainian membership, but rather that it was (again) pushing back the timetable. As Fried said to the Ukrainian FM on 6 September 2006, “…the U.S. and the alliance would respond if Ukraine demonstrated the serious political will to join NATO and do the work necessary to meet all the standards, not just in military reform. President Bush’s guidance had been clear on this point for the past six years: if a country really wanted to join and was ready, the U.S. would make it happen.”[43]

Indeed, at the Riga Summit, President Bush emphasized that “as democracy takes hold in Ukraine and its leaders pursue vital reforms, NATO membership will be open to the Ukrainian people if they choose it” (Bush, 2006a).

The U.S.’s 2008 pursuit of MAPs for Ukraine and Georgia

The NATO Freedom Consolidation Act—introduced on 6 February 2007, passed unanimously (i.e. without objection) in both the House and the Senate, and enacted without modification on 9 April 2007—called for “the timely admission of Albania, Croatia, Georgia, Macedonia (FYROM), and Ukraine” into NATO, urged NATO allies to support a MAP for Georgia, and designated all five states as eligible to receive assistance under the Program to Facilitate Transition to NATO Membership that was established by the NATO Participation Act of 1994.[44] The Program not only heavily implied that any designated beneficiaries of it were destined to “transition to NATO membership,” but also included substantive elements to make that happen, giving beneficiaries military assistance directed at yielding: “(1) joint planning, training, and military exercises with NATO forces; (2) greater interoperability of [equipment]; and (3) conformity of military doctrine and also making beneficiaries eligible for an array of other military assistance in the form of financing, training, the transfer of military equipment, etc.”[45]

This was followed by Senate Resolution 439, introduced 31 January 2008 and adopted 14 February 2008, which explicitly called for the U.S. to “take the lead in supporting the awarding of a Membership Action Plan to Georgia and Ukraine as soon as possible.” Notably, the Resolution was introduced by a wide spectrum of prominent Senators, including Biden, Obama, Lugar, Lieberman, Graham, and McCain. And, like the NATO Freedom Consolidation Act, it was adopted unanimously.[46]

Then, as NATO’s Bucharest Summit drew near, President Bush repeatedly identified MAPs for Ukraine and Georgia as his objective (Bush, 2006b, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). Once in Bucharest, Bush continued to make the same points (Bush, 2008d), for example: “…we must make clear that NATO welcomes the aspirations of Georgia and Ukraine [to] membership in NATO and offers them a clear path forward to meet that goal. So my country’s position is clear: NATO should welcome Georgia and Ukraine into the Membership Action Plan. And NATO membership must remain open to all of Europe’s democracies that seek it and are ready to share in the responsibilities of NATO membership” (Bush, 2008e). (He also insisted that Russia has no “veto” and that it is in Russia’s interest to have “democracies on [its] border” (Bush, 2008f)).

As NSC Director for Europe Damon Wilson put it, the U.S. “expended a tremendous amount of political capital” on its effort at Bucharest.[47] Ultimately, this was partly successful, yielding on 3 April 2008 a Summit Declaration that read: “NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO. … MAP is the next step for Ukraine and Georgia on their direct way to membership. Today we make clear that we support these countries’ applications for MAP. Therefore, we will now begin a period of intensive engagement with both at a high political level to address the questions still outstanding pertaining to their MAP applications. We have asked Foreign Ministers to make a first assessment of progress at their December 2008 meeting. Foreign Ministers have the authority to decide on the MAP applications of Ukraine and Georgia.”

Thus, as an 8 April 2008 cable from the U.S. Mission to NATO put it: “While Allies delayed a decision to move Ukraine and Georgia into the…MAP process, Allies more importantly agreed that Ukraine and Georgia will become NATO members. The question is now ‘when’, not ‘if’[,] and MAP could come as early as NATO’s December Foreign Ministerial.”[48]

The U.S. now turned to winning those December MAPs.

This objective received legislative endorsement when, on 28 April 2008, Senate Resolution 523 was unanimously adopted. The Resolution—whose sponsors included Biden, Obama, Lugar, Hillary Clinton, and McCain—“supports the declaration of the Bucharest Summit…that Ukraine and Georgia will become members of NATO” and “urges the foreign ministers of NATO…at their meeting in December 2008 to consider favorably the applications of … Ukraine and Georgia for Membership Action Plans.”[49]

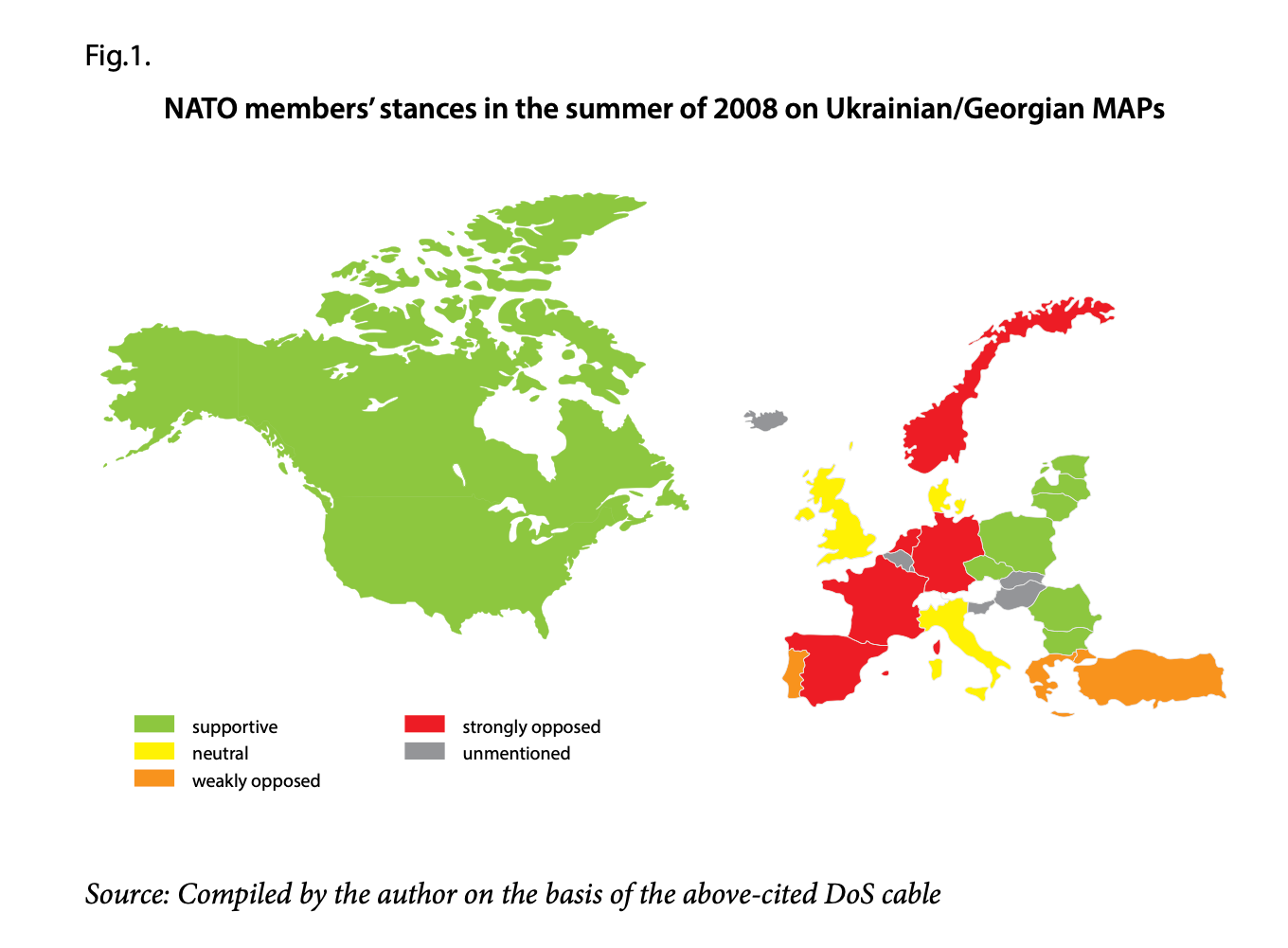

After Bucharest, the U.S. sought to build the same sort of unity amongst its allies that—as demonstrated by Resolution 523—already existed within the U.S. itself. However, as the U.S. Mission to NATO reported on 27 June 2008, “discussion of Ukrainian and Georgia[n] MAP prospects at NATO remains highly charged and polarized,” thus leaving uncertain “the prospect for Ukrainian [and] Georgian MAP attainment at or before the December NATO Foreign Ministerial.”[50] Based on the cable’s report, NATO members can be divided into five groups in terms of their (perceived) stances on Ukrainian/Georgian MAPs: supportive, neutral, weakly opposed, strongly opposed, and unmentioned (Fig.1).

The cable, sent to virtually the entire U.S. government (including the CIA), requested suggestions of “any ‘soft spots’ on advocacy which we should explore.” The cable bemoaned Germany’s focus on ensuring a “compensation strategy for Russia,” its insistence “that Ukrainian MAP must be shown to benefit ‘all of Europe’s security,’” and its “active denial that the Bucharest statement already agreed [on] membership for both aspirants.” And the cable referred to Germany and Italy “fishing” to set up a working group that would consider the “Russian strategic calculus” in the context of Ukrainian/Georgian MAP/membership—an effort which, the cable implies, was opposed by the U.S.

Thus, in mid-2008, the U.S. was persistently lobbying for Ukrainian/Georgian MAPs but found the majority of NATO—and all of ‘old’ NATO members besides Canada—to be skeptical or outright opposed, inter alia out of concern about the Russia-related strategic consequences of expansion. (An issue that the U.S. tried to exclude from discussion altogether.)

But this opposition was not necessarily insurmountable. The U.S., given enough time, could push almost anything through NATO, as demonstrated by the Baltics’ membership and by the Bucharest membership pledge itself. (Hence, when a Ukrainian official asked in 2006 “whether [Kiev] could count on U.S. support to convince skeptical alliance members on MAP[,] if Ukraine did its part,” Daniel Fried answered that “if a country really wanted to join and was ready, the U.S. would make it happen.”[51])

Accordingly, by July 2008, the U.S. was breaking through. On 22 July 2008, Fried was told by NATO’s Secretary-General that the latter “did not see Germany or France softening their opposition to a positive decision [on MAPs] in December [2008],” but that Chancellor Angela Merkel “had floated the idea of deciding in December [2008] that Ukraine and Georgia would get MAP[s] in 2010.”[52] As the above-cited 27 June 2008 cable noted, “as Germany goes, so goes the prospect for Ukrainian [and] Georgian MAP attainment,”[53] so this apparent shift in the German position likely meant that the U.S. would be able to get Ukraine and Georgia their MAPs, after all—albeit with a further two-year delay.

However, there was a caveat to the Germans’ concession: they would commit, in December 2008, to granting the MAPs in 2010—“unless something terrible happened.” And something terrible did happen, just 13 days after Fried’s meeting with the NATO Secretary-General, when Georgia went to war with Russia. This ended the reluctant willingness of Germany, and other European expansion-skeptics, to give Georgia and Ukraine MAPs and eventual membership.

Continuing U.S. intention to admit Ukraine and Georgia

Yet the U.S. remained determined to admit them.

On 24 October 2008, Bush said that “I reiterate America’s commitment to the NATO aspirations of Ukraine, Georgia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Montenegro” (Bush, 2008g). Then, on 19 December 2008 and 9 January 2009, the U.S. signed Charters on Strategic Partnership with Ukraine[54] and Georgia.[55] The Charters reaffirmed the Bucharest membership pledge and committed to strengthening the states’ candidacies, including by strengthening their militaries. (Ukraine’s was renewed on 10 November 2021. The new version maintained a reference to the Bucharest Summit membership pledge, while adding that the “United States supports Ukraine’s right to decide its own future foreign policy course[,] free from outside interference, including with respect to Ukraine’s aspirations to join NATO.”[56])

And this support for Ukrainian and Georgian membership did not end with the Bush Administration. To the contrary, as early as 5 March 2009—the day before presenting Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov with a Reset/Overload Button—U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was saying that “we should continue to open NATO’s door to European countries such as Georgia and Ukraine and help them meet NATO standards” (Reuters, 2009). (And the U.S. did help. For instance, even more than a decade later, in August 2021, the U.S. and Ukraine concluded a Strategic Defense Framework, in which the U.S. promised, inter alia: a “robust training and exercise program”; a “closer partnership of defense intelligence” in “military planning and defensive operations”; and support for “defense sector reforms, in line with NATO principles and standards.”[57])

De facto NATO expansion to Ukraine

Although Ukraine never did receive formal membership, it has still de facto partly entered NATO.

In June 2008, Ukraine joined the NATO Response Force (NRF), a rapid-deployment formation under NATO command.[58] In July 2016, NATO launched its Comprehensive Assistance Package for Ukraine, providing advice, training, and joint exercises with the intent of assisting Ukraine to “reform its Armed Forces according to NATO standards and to achieve their interoperability with NATO forces by 2020.”[59] And in June 2020, Ukraine was designated an Enhanced Opportunity Partner,[60] providing “preferential access to NATO’s interoperability toolbox, including exercises, training, exchange of information and situational awareness.”[61]

Aside from formal NATO institutions, by 2021, more than 12 NATO members had sent military advisors to Ukraine (including 150 just from the U.S. Special Forces and National Guard) (Schwirtz, 2021). And between 2014 and 23 February 2022, NATO members showered Ukraine in weaponry. The U.S. alone provided materiel—including sniper rifles, anti-tank missiles, armored vehicles, reconnaissance drones, radar systems, night vision equipment, and radio equipment[62]—worth about $2 billion in 2014-2020,[63] $450 million in 2021 (Brennan and Watson, 2022), and $200 million in just the few weeks immediately preceding 24 February 2022 (McLeary and Swan, 2022). Aside from the U.S., Canada provided trainers, the UK provided armored vehicles, anti-tank missiles, and trainers, the Czech Republic provided artillery ammunition, Poland provided anti-air missiles, the Baltic states provided anti-air and anti-tank missiles, and Turkey provided lethal drones (Cheng, 2022; Reuters, 2022; Hille, 2022). And this is surely an incomplete list. By one estimate, NATO and its members altogether provided equipment worth $14 billion to Ukraine between 2014 and 2021(Seibt, 2022), which would amount to 42% of Ukraine’s military expenditure ($33.6 billion (SIPRI, nd.)) in the same time period.

* * *

In sum, the U.S.’s pursuit of Ukraine’s membership in NATO began almost as soon as Ukraine became independent. It was not a response to objectively- or subjectively-threatening Russian actions, but instead began during the U.S.-Russian honeymoon, at a time when Russia was seeking entry into the West, largely subservient to the U.S., and struggling to merely survive as a state. In fact—alongside NATO allies’ cautiousness, and occasional disagreement within Ukraine itself—Russian military operations have been the only factors preventing Ukrainian accession from being fully achieved, while Russian diplomacy and offers of compromise have been consistently rejected by the U.S., and entirely unsuccessful.

It is ironic that NATO, an alliance ostensibly committed to preserving peace in Europe, has once again made war the ultima ratio, the only effective way for a state to preserve its security. But such an outcome was essentially predetermined almost as soon as the USSR collapsed, when the U.S. decided to expand NATO into Ukraine.

Asmus, R., 2002. Opening NATO’s Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New Era. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Brennan, M. and Watson, E., 2022. US and NATO to Surge Lethal Weaponry to Ukraine to Help Shore Up Defenses against Russia. CBS News, 20 January. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230608021106/https://www.cbsnews.com/news/u-s-nato-ukraine-weapons-defense-russia/ [Accessed 8 June 2023].

Bush, G., 2005. The President’s News Conference with Secretary General Jakob Gijsbert ‘Jaap’ de Hoop Scheffer of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 22 February. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230610000936/https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2005/02/20050222-3.html [Accessed 10 June 2023].

Bush, G., 2006a. Remarks at Latvia University in Riga. 28 November. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230908133132/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-latvia-university-riga [Accessed 8 September 2023].

Bush, G., 2006b. Remarks Following Discussions with President Mikheil Saakashvili of Georgia. 19 March. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20231129181817/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-following-discussions-with-president-mikheil-saakashvili-georgia-and-exchange-with [Accessed 29 November 2023].

Bush, G., 2008a. Interview with Foreign Print Journalists. 26 March. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230903141423/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/interview-with-foreign-print-journalists-6 [Accessed 3 September 2023].

Bush, G., 2008b. Remarks at a Luncheon Hosted by President Viktor Yushchenko of Ukraine in Kiev. 1 April. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230902192212/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-luncheon-hosted-president-viktor-yushchenko-ukraine-kiev [Accessed 2 September 2023].

Bush, G., 2008c. The President’s News Conference with President Viktor Yushchenko of Ukraine in Kiev. 1 April. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230902191637/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/the-presidents-news-conference-with-president-viktor-yushchenko-ukraine-kiev-ukraine [Accessed 2 September 2023].

Bush, G., 2008d. Remarks Following a Discussion with Secretary General Jakob Gijsbert ‘Jaap’ de Hoop Scheffer of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in Bucharest. 2 April. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230906162530/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-following-discussion-with-secretary-general-jakob-gijsbert-jaap-de-hoop-scheffer [Accessed 6 September 2023].

Bush, G., 2008e. Remarks in Bucharest, Romania. 2 April. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230911054008/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-bucharest-romania [Accessed 11 September 2023].

Bush, G., 2008f. The President’s News Conference with President Traian Basescu of Romania in Neptun, Romania. 2 April. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230902191640/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/the-presidents-news-conference-with-president-traian-basescu-romania-neptun-romania [Accessed 2 September 2023].

Bush, G., 2008g. Remarks at a Signing Ceremony for North Atlantic Treaty Organization Accession Protocols for Albania and Croatia. 24 October. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230902204933/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-signing-ceremony-for-north-atlantic-treaty-organization-accession-protocols-for [Accessed 2 September 2023].

Bush, G. and Yushchenko, V., 2005. Joint Statement: A New Century Agenda for the Ukrainian-American Strategic Partnership. 4 April. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240213211825/https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2005/04/20050404-1.html [Accessed 13 February 2024].

Cheng, A., 2022. Military Trainers, Missiles, and over 200,000 lbs of Lethal Aid: What NATO Members Have Sent Ukraine So Far. The Washington Post, 22 January. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20221024135124/https://www.stripes.com/theaters/europe/2022-01-22/military-trainers-missiles-lethal-aid-nato-ukraine-4378966.html [Accessed 24 February 2024].

CRS, 2004. Ukraine: Background and US Policy. Congressional Research Service, 27 February. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240206101756/https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20040227_RL30984_528da393b4c8455bee4f9acc82538d51bbe47acf.pdf [Accessed 6 February 2024].

Duben, B.A., 2022. The Long Shadow of the Soviet Union: Demystifying Putin’s Rhetoric Towards Ukraine. LSE IDEAS Strategic Update. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220706013734/http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/114493/1/Duben_the_long_shadow_of_the_soviet_union_published.pdf [Accessed 6 July 2022].

Goldgeier, J., 2023. NATO Enlargement Didn’t Cause Russia’s Aggression. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230802123308/https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/07/31/nato-enlargement-didn-t-cause-russia-s-aggression-pub-90300 [Accessed 2 August 2023].

Hille, P., 2022. Who Supplies Weapons to Ukraine? Deutsche Welle, 14 February. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20231204113114/https://www.dw.com/en/russia-ukraine-crisis-who-supplies-weapons-to-kyiv/a-60772390 [Accessed 4 December 2023].

Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation, 2002. Mission and Aims. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20020708202033/http://ieac.org.ua/eng/about/index.shtml?id=25 [Accessed 8 July 2023].

International Republican Institute. 2021. Public Opinion Survey of Residents of Ukraine: March 13-21, 2021. March. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230131011447/https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/public_-_03.2021_national_eng-_public.pdf [Accessed 31 January 2023].

Kiev International Sociological Institute, 2021. Otnoshenie k vstupleniyu Ukrainy v ES i NATO, otnoshenie k pryamym perevogoram s V. Putinym i vospriyatie voyennoi ugrozy so storony Rossii: Rezultaty telefonnogo oprosa, provedennogo 13-16 dekabrya 2021 goda. [Attitude to Ukraine’s Accession to NATO, Attitude to Direct Negotiations with V. Putin and Perception of the Military Threat from Russia: Results of a Telephone Survey Conducted on December 13-16, 2021]. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20221210162742/kiis.com.ua/?lang=rus&cat=reports&id=1083 [Accessed 10 December 2022].

Kostenko, Y., 2021. Ukraine’s Nuclear Disarmament: A History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kramer, D., 2006. Ukraine and NATO. Remarks at the US-Ukraine Security Dialogue Series. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220428205037/https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/eur/rls/rm/68408.htm [Accessed 28 April 2022]

Lake, A., 1994. Memorandum for the President. With attached NSC staff paper Moving Toward NATO Expansion. 12 October. Clinton Library Box 481, Folder 9408265, 2015-0755-M. P. 63-78 (PDF pagination). Available at: https://goo.su/fCGDU [Accessed 3 April 2024].

McLeary, P. and Swan, B.W., 2022. US Approves Allied Weapons Shipments to Ukraine as Worries Mount. Politico, 19 January. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20221227221108/https://www.politico.com/news/2022/01/19/us-allies-ukraine-weapons-russia-invasion-527375 [Accessed 27 December 2022].

President of Ukraine, 2002. Ukaz #190. 26 February. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220308174405/zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/190/2002#Text [Accessed 8 March 2022].

Reuters, 2009. Clinton Says NATO Must Make Fresh Start with Russia. Reuters, 5 March. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20210516072402/https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL5564217 [Accessed 16 May 2021].

Reuters, 2022. Factbox: Ukraine Gets Weapons from the West but Says It Needs More. Reuters, 25 January. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230324001123/https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraine-gets-weapons-west-says-it-needs-more-2022-01-25/ [Accessed 24 March 2023].

RIA Novosti, 2002. Prezident Ukrainy podpisal ukaz o vvedenii v silu resheniya Soveta natsionalnoi bezopasnosti i oborony strany o vstuplenii Ukrainy v NATO [President of Ukraine Signs a Decree on Enforcing the National Security Council’s Decision on NATO Membership]. Ria Novosti, 9 July. [Accessed 11 September 2022].

Sakhno, Yu., 2019. Geopoliticheskiye oriyentatsii zhitelei Ukrainy: Fevral 2019. Kiyevsky mezhdunarodny institut sotsiologii [Geopolitical Orientations of the Citizens of Ukraine: February 2019. Kiev International Institute of Sociology]. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20210417120204/kiis.com.ua/?lang=rus&cat=reports&id=827 [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Sarotte, M.E., 2021. Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Seibt, S., 2022. Is the Ukrainian Military Really a David against the Russian Goliath? France 24, 20 January. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230826015819/https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20220120-is-the-ukrainian-military-really-a-david-against-the-russian-goliath [Accessed 26 August 2023].

SIPRI, nd. Military Expenditure Database. Available at: sipri.org/databases/milex [Accessed 1 January 2024].

Schwirtz, M., 2021. NATO Signals Support for Ukraine in Face of Threat from Russia. New York Times, 16 December. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20231106132929/https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/16/world/europe/ukraine-nato-russia.html [Accessed 6 November 2023].

Woehrel, S., 2006a. Ukraine: Current Issues and US Policy. Congressional Research Service, 7 June. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240209170825/https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20060607_RL33460_bb905122710efbabebfa1a851c3875fdc9b54986.pdf [Accessed 9 February 2024].

Woehrel, S., 2006b. Ukraine: Current Issues and US Policy. Congressional Research Service, 23 August. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240209170825/https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20060823_RL33460_63076fc65c44846685739be3db8e5f6d2e2dbb1f.pdf [Accessed 9 February 2024].

Vershbow, A., 2019. Ch.18: Present at the Transformation: An Insider’s Reflection on NATO Enlargement, NATO-Russia Relations, and Where We Go From Here. In: D. Hamilton and K. Spohr, K. (eds.) Open Door: NATO and Euro-Atlantic Security After the Cold War. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

___________

[1] DoS, 1993(7 Sep). Strategy for NATO’s Expansion and Transformation. Memo from Lynn Davis to the Secretary of State. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220313081603/nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/16374-document-02-strategy-nato-s-expansion-and [Accessed 13 March 2022].

[2] DoS, 1994(15 Oct). Note for Strobe Talbott. Cable from Nick Burns to Strobe Talbott. C06835794. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102459/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_L_Nov2021_C/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06835794/C06835794.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[3] DoS, 1996(1 Feb). Deputy Secretary Talbott’s January 18 Meeting with Ukraine Ambassador Tarasyuk. Cable from USNATO to the Secretary of State. C06698130. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240403182020/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Apr2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06698130/C06698130.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2024].

[4] DoS, 1996(16 Apr). The Deputy Secretary’s Meeting with Estonian Foreign Minister Kallas, March 25. Cable from the Secretary of State to Embassy Tallinn. C06697970. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102439/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_Jun2019_2020/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06697970/C06697970.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[5] DoS, 1996(2 Oct). Deputy Secretary’s 9/16 and 9/19 Meetings with Ukrainian NSDC Secretary Horbuyn. Cable from Embassy Vienna to USDEL CSCE. C06698651. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102448/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_Aug2019_2020/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06698651/C06698651.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[6] DoS, 1997(15 Jun). Deputy Secretary Meeting with Ukrainian Ambassador Shcherbak. Cable from Embassy Vienna to Embassy Kiev. C06703280. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102452/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Sep2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06703280/C06703280.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[7] DoS, 1997(15 Jun). Deputy Secretary Meeting with Ukrainian Ambassador Shcherbak. Cable from Embassy Vienna to Embassy Kiev. C06703280. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102452/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Sep2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06703280/C06703280.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[8] DoS, 1993(5 Oct). Your October 6 Lunch Meeting with Secretary Aspin and Mr. Lake. Cable from Robert Gallucci to the Secretary of State. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220310190110/nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/16377-document-05-your-october-6-lunch-meeting [Accessed 10.03.2022].

[9] DoS, 1996(1 Feb). Deputy Secretary Talbott’s January 18 meeting with Ukraine Ambassador Tarasyuk. Cable from USNATO to the Secretary of State. C06698130. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240403182020/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Apr2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06698130/C06698130.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2024].

[10] DoS, 1996(28 Feb). Ukraine FM Udovenko’s Meeting with Amb. Collins. Cable, unknown sender and receiver. C06698242. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102443/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Apr2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06698242/C06698242.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[11] DoS, 2003(11 Dec). 03ANKARA7611. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240209154151/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/03ANKARA7611_a.html [Accessed 9 February 2024].

[12] DoS, 1996(16 Jul). Memo from Strobe Talbott to the Secretary of State. C06570196. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102435/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11926/DOC_0C06570196/C06570196.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[13] DoS, 1996(29 Jul). NATO-Russia: Objectives, Obstacles, and Work Plan. C06570185. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240403183847/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11899/DOC_0C06570185/C06570185.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2024].

[14] DoS, 1997. (24 Mar) Official Informal. Cable from USNATO to the Secretary of State. C06703619. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240404102456/https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Sep2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06703619/C06703619.pdf [Accessed 4 April 2024].

[15] House of Representatives, 1996. Vote #338. 23 July. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220628211513/https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/104-1996/h338 [Accessed 28 June 2022].

[16] Senate, 1996. Vote #245. 25 July. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220826151022/senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_votes/vote1042/vote_104_2_00245.htm [Accessed 26 June 2022].

[17] US Law, 1996(30 Sep). Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Act, 1997. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220506005210/https://www.congress.gov/bill/104th-congress/house-bill/3610/text/pl [Accessed 6 May 2022].

[18] DoS, 2006(26 Jan). 06KIEV336. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230222073017/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV336_a.html [Accessed 22 February 2023].

DoS, 2006(15 Feb). 06KIEV604. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220302012513/wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV604_a.html [Accessed 2 March 2022].

[19] See, for example: Sakhno, 2019; International Republican Institute, 2021; Kiev International Sociological Institute, 2021.

[20] NED, 2002-2009. Annual Reports.

[21] NATO, 2002. NATO-Ukraine Action Plan. 22 November. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240117042013/https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_19547.htm [Accessed 17 January 2024].

[22] DoS, 2006(26 Apr). 06KIEV1639. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210090956/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV1639_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

DoS, 2006(28 Apr). 06KIEV1693. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054633/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV1693_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2022].

DoS, 2006(18 Sep). 06KIEV3553. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054633/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3553_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2022].

[23] DoS, 2007(15 Aug). 07KYIV2001. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054633/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/07KYIV2001_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2022].

[24] DoS, 2006(26 Jan). 06KIEV336. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230222073017/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV336_a.html [Accessed 22 February 2023].

[25] DoS, 2006(14 Mar). 06SOFIA372. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210093042/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06SOFIA372_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[26] DoS, 2006(15 Mar) . 06BUCHAREST447. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210093059/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06BUCHAREST447_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[27] DoS, 2006(9 Nov). 06PARIS7340. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210093200/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06PARIS7340_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[28] NATO, 2005. NATO Launches ‘Intensified Dialogue’ with Ukraine. 21 April Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230531064417/https://www.nato.int/docu/update/2005/04-april/e0421b.htm [Accessed 31 May 2023.

[29] DoS, 2005(9 Sep)a. 05PARIS6125. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230221173818/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/05PARIS6125_a.html [Accessed 21 February 2024].

DoS. (7 Oct) 2005. 05THEHAGUE2708. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210093217/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/05THEHAGUE2708_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[30] DoS, 2005(9 Sep)b. 05PARIS6125. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230221173818/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/05PARIS6125_a.html [Accessed 21 February 2024].

[31] DoS, 2005(7 Oct). 05THEHAGUE2708. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210093217/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/05THEHAGUE2708_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[32] DoS, 2006(15 Feb). 06KIEV604. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054633/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV604_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2023].

[33] DoS, 2006(26 Apr). 06KIEV1639. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210090956/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV1639_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[34] DoS, 2006(16 Mar). 06KIEV1036. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220309062648/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV1036_a.html [Accessed 9 March 2023].

[35] DoS, 2006(26 Apr). 06KIEV1639. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210090956/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV1639_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[36] DoS, 2006(2 Jun). 06BERLIN1494. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20231201222854/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06BERLIN1494_a.html [Accessed 1 December 2023].

[37] DoS, 2006(11 Aug). 06KIEV3130. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210093910/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3130_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[38] DoS, 2006(31 Jul). 06KIEV2962. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210094439/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV2962_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[39] DoS, 2006(4 Aug). 06KIEV3029. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210094446/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3029_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

DoS, 2006(11 Sep). 06KIEV3489. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210094454/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3489_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

DoS, 2006(18 Sep). 06KIEV3553. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054633/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3553_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2022].

[40] DoS, 2006(11 Aug). 06KIEV3130. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210093910/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3130_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[41] DoS, 2006(18 Sep). 06KIEV3570. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210094342/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3570_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[42] DoS, 2006(8 Sep). 06KIEV3463. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210094339/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3463_a.html [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[43] DoS, 2006(18 Sep). 06KIEV3553. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054633/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3553_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2023].

[44] US Law, 2007. NATO Freedom Consolidation Act of 2007. 9 Apil 2007. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20210729211313/https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/110/s494 [Accessed 29 July 2023].

[45] US Law, nd. 22. USC.1928. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20200331114103/http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:22 section:1928 edition:prelim) [Accessed 31 March 2024].

[46] Senate, 2008. A Resolution Expressing the Strong Support of the Senate for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to Enter into a Membership Action Plan with Georgia and Ukraine. 14 February. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20221017054821/https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-resolution/439/text [Accessed 17 October 2022].

[47] Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, 2018. Hearing: Russia’s Occupation of Georgia and the Erosion of the International Order. 17 July 2018. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210095332/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115jhrg30828/html/CHRG-115jhrg30828.htm [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[48] DoS, (8 Apr) 2008. 08USNATO122. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20190711111241/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08USNATO122_a.html [Accessed 11 July 2023].

[49] Senate, 2008. A Resolution Expressing the Strong Support of the Senate for the Declaration of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization at the Bucharest Summit that Ukraine and Georgia Will Become Members of the Alliance. 28 April 2008. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20201028194815/https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/senate-resolution/523/text [Accessed 28 October 2023].

[50] DoS, (27 Jun) 2008. 08USNATO225. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054651/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08USNATO225_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2023].

[51] DoS, 2006(18 Sep). 06KIEV3553. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054633/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06KIEV3553_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2023].

[52] DoS, 2008(25 Jul). 08USNATO265. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20210608234158/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08USNATO265_a.html [Accessed 8 June 2023].

[53] DoS, 2008(27 Jun). 08USNATO225. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220930054651/https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08USNATO225_a.html [Accessed 30 September 2023].

[54] DoS, 2008(19 Dec). United States – Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230129202721/https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/eur/rls/or/113366.htm [Accessed January 2023].

[55] DoS, 2009(9 Jan). United States – Georgia Charter on Strategic Partnership. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240210004709/https://www.state.gov/united-states-georgia-charter-on-strategic-partnership/ [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[56] DoS, 2021(10 Nov). US-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240117055412/https://www.state.gov/u-s-ukraine-charter-on-strategic-partnership/ [Accessed 17 January 2024].

[57] DoD, 2021. Fact Sheet — US-Ukraine Strategic Defense Framework. 31 August. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20240208181205/https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/31/2002844632/-1/-1/0/US-UKRAINE-STRATEGIC-DEFENSE-FRAMEWORK.PDF [Accessed 10 February 2024].

[58] NATO, 2008. Defense Ministers of the NATO-Ukraine Commission. Joint Statement. 13 June. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20230406212813/https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_1292.htm [Accessed 6 April 2023].

[59] NATO, 2016. Comprehensive Assistance Package for Ukraine. July. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220319215217/https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2016_09/20160920_160920-compreh-ass-package-ukra.pdf [Accessed 19 March 2023].

[60] NATO, 2022a. Partnership Interoperability Initiative. 22 February. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220709065216/https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_132726.htm [Accessed 9 July 2022].

[61] NATO, 2022b. Relations with Ukraine. 8 July.Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220916181956/https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_37750.htm [Accessed 16 September 2023].

[62] NATO, 2016. Comprehensive Assistance Package for Ukraine. July. Available at: web.archive.org/web/20220319215217/https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2016_09/20160920_160920-compreh-ass-package-ukra.pdf [Accessed 19 March 2024].

[63] 2.5b in 2014-2021 (Reuters, 2022) minus 450m in 2021.