Since I wrote this in August 2016 Donald Trump won a majority of the Electoral College, though he came in second to Hillary Clinton in the popular vote. The Republicans control both the House and Senate, again even though the Democrats received more votes. The U.S. Constitution and biased district lines for the House gave the Republicans an advantage. Congressional Republicans are committed to quickly passing extreme neoliberal policies: eliminating Obamacare, privatizing Medicare (the health program for the elderly), public lands, and the student loan program. They also want to eliminate the Dodd Frank bill that regulated banks after 2008 as well as much environmental and workplace and consumer safety regulation. All these plans are the opposite of what Trump suggested he would do to protect (white) Americans who have been harmed by elites. We can look forward to a deeper nationalist/racist reaction, as American voters do not get the economic relief that Trump promised. We will see if the next step is a turn by those voters to the left (perhaps to a younger version of Bernie Sanders) or an eruption of violence against minorities, immigrants and intellectuals whom Trump no doubt will blame for his failings and betrayals.

In 2016 elites appear to be under challenge in rich as well as poorer countries. Poor countries understandably have populations that are angry and disillusioned about their leaders. After all, in most poor countries leaders are unable to prevent their citizens from being exploited economically by outside powers. Often the leaders who emerge in such circumstances, or who are installed by colonial or neocolonial powers, are corrupt and repressive. Such conditions spur passive cynicism or active rebellion.

What is new and unusual is that citizens of rich countries also are angry and disillusioned. Most spectacularly, Britain voted to leave the EU. The heaviest majorities for Brexit came in Wales and poor English communities that are the biggest bene?ciaries of EU subsidies, which they will lose if and when Britain actually leaves the EU.

Donald Trump’s supporters, like those who backed ‘Tea Party’ candidates for Congress are for the most part comfortable retirees, government employees, or bene?ciaries of social welfare programs directed at disabled and elderly whites. While Trump is unlikely to win in November, the fact that he could capture a major party nomination, and that other candidates who share his racist and anti-immigrant views now dominate the Republican majority in Congress, indicates that this is not a momentary aberration but a strong tendency in American politics that will not disappear anytime soon even if Trump is decisively defeated for president.

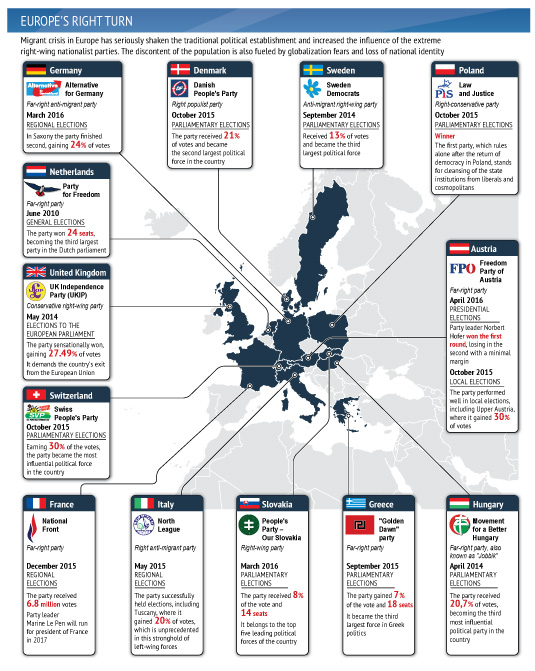

Trump-like politicians are prominent in Europe too. A neo-Nazi came within few thousand votes of being elected president of Austria. Le Pen, father and daughter, and their National Front are a permanent in?uence on French politics even though they so far have been unable to win any significant of?ces. The leaders of the Brexit bloc, Boris Johnson (now Foreign Secretary) and Nigel Farage, are on record for making openly racist statements. The only Western country where the extreme right controls the government, so far, is Hungary under Viktor Orban.

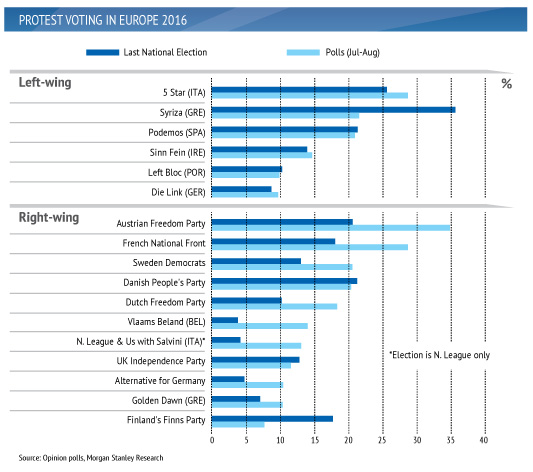

Leftist challenges to elites also enjoy a measure of popularity. We need to remember that Bernie Sanders got almost as many votes in the Democratic primaries as Trump did in the Republican. The Blairite neoliberals who dominated the British Labour party were overwhelmingly rejected in favor of longtime leftist Jeremy Corbyn. Greece elected Syriza on an anti-austerity platform. New leftwing parties have won substantial parliamentary blocs in Spain, Italy, and elsewhere. While those parties that control governments, above all Syriza, have gone back on their election promises and accepted austerity demands from the Troika of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and international Monetary Fund, their elections nevertheless express profound opposition to the European elites and local elites and politicians who have embraced and enforced austerity. Lawrence Summers (2016), the former U.S. Treasury Secretary who was a key advocate of financial deregulation in the 1990s, recently wrote “the willingness of publics to be intimidated by experts into supporting cosmopolitan outcomes appears, for the moment, to have been exhausted.”

Are the new leftist and rightist forces genuine challenges to elite power? Do they express a fundamental reordering of the relationship between elites and masses? Clearly, both left and right insurgent politicians and their supporters articulate profound disquiet with existing policies, politicians, and institutional structures. Voters and supporters of Trump, Brexit, the National Front, Jeremy Corbyn, Syriza, and others believe that the main parties are corrupt and serve the interests of rich capitalists, foreign interests, or immigrants and minorities. Where the left and right disagree is on the sources of and solutions to political corruption and to what large segments of the public perceive as declines in the quality of their lives and communities.

Left parties and politicians focus on the ways in which transnational corporations, above all the giant financial firms, have usurped decision about the distribution of wealth and the allocation of resources from elected officials. The more perceptive of these critics note, as Pierre Bourdieu put it, “Paradoxically, it is states that have initiated the economic measures (of deregulation) that have led to their economic disempowerment. And contrary to the claims of both the advocates and critics of the policy of ‘globalization,’ states continue to play a central role by endorsing the very policies that consign them to the sidelines” ([2001] 2003, p. 14). Of course, deregulation, and the globalization of production and commerce that the loosening of government controls has allowed, affects different social groups and regions unevenly. Industrial workers, service workers who are not unionized, and people outside the largest cities have suffered the greatest income declines. The poorer countries in southern and Eastern Europe, and the ‘Anglo’ countries — the U.S., UK, Australia and New Zealand — have seen the greatest cuts in social benefits, although here again the effects within those countries are uneven. Children and the poor have lost absolutely, while in some countries the elderly and workers with seniority have been spared most of the effects of social spending cuts.

The enrichment of the top 1% (or more accurately the top 0.1%) since the 1980s, documented by Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013), has been at the expense of everyone else, but it has been made possible by financial deregulation, union busting, and trade agreements that shift manufacturing to low wage countries. The shift in income and wealth from the middle classes, created by government policies in North America and both Eastern and Western Europe in the decades after 1945, to an ever-smaller elite is accompanied by the feeling that decisions are beyond democratic control. As jobs move to cheaper locations, communities are destroyed. Investment in infrastructure, once paid for with progressive taxes, has declined, and the degradation of public transportation, roads and bridges, schools, hospitals, and other public goods is a daily sensory reminder of governmental weakness. The ubiquitous media coverage of the lavish spending and global interactions of the rich further enforces the view that a uni?ed transnational elite makes the important decisions away from public scrutiny and that the members of that elite have more in common with each other than with the citizens of their own nations.

Both left and right criticize trade agreements and the growing power of international agencies, such as the IMF and WTO. The National Front in France and Syriza both present the EU and international agencies as villains. Donald Trump, re?ecting his supporters’ and his own ignorance about world governance, blames speci?c foreign governments, above all China and Mexico, for America’s trade de?cits and the export of manufacturing jobs. The rightists almost never mention capitalists, the rich, or corporations in their indictments of what is wrong. Leftists do offer criticisms of capitalists, although recently their preferred label is the 1%. However, even leftists today direct most of their ?re against their own governments or international agencies. Once the Marxist and non-Marxist left agreed that governments did the bidding of capitalists but they believed that a revolution or electoral victory could lead the state to serve workers instead. Now leftist rhetoric suggests that international agencies have the initiative while the rich are almost passive bene?ciaries of globalization policies. Such an analysis is substantively wrong. It also is an error politically, since it directs powerful feelings of resentment and envy at government of?cials rather than the far more privileged, and still largely invisible, capitalists. Most signi?cantly, blaming international agencies bleeds into blaming domestic politicians and governments and undermines the possibility of convincing voters that a different government could reverse neoliberal policies and bring real bene?ts to their supporters.

Cynicism about politics is compounded by neoliberalism. Just as a “legitimation crisis” in the 1970s provided an opening for economists and politicians to present neoliberal solutions (Krippner. 2011), so too does the current “crisis of political legitimacy [allow] critics of state intervention…to delegitimize the intervention of the state on behalf of the public interest… because people do not trust their political representatives, governments have a relatively small margin for daring decisions” (Castells. 2011, pp. 194-95). Schafer and Streeck (2013) ? nd that voting participation declined in all OECD countries when austerity was imposed, and most strongly among those strata affected most heavily by cuts in social programs. They argue that democracy is being replaced by a ‘post-democracy’ of spectacles and that states now respond more to the views of financiers, expressed in periodic auctions of government bonds, than they do to voters in regularly scheduled elections.

The main way that the right differs from the left is in their blame of immigrants and minority groups. Rightist politicians falsely assert that budgets are in crisis because immigrants or lazy minorities are absorbing so much money in welfare grants. Racist politicians promise to preserve existing bene?ts: Trump says he opposes any cuts to Social Security (the U.S. old age pension), while Marine Le Pen promises increases in social bene?ts for ‘real’ French people, just as the Nazis promised and delivered bene? ts for ‘real’ Germans during their twelve years in power. However, to actually deliver on those promises, Trump, Le Pen, and others of their ilk would have to challenge neoliberal policies and increase taxes on their wealthy benefactors. Until one of these demagogues or nativist parties wins power we can’t know if they would keep their promises to their mass base or would instead maintain the conservative neoliberal orthodoxy. The French National Front is such a marginalized party that their ties to capitalists are weak, and they very well might increase taxes on capital to reward their mass base.As the of? cial candidate of the Republican Party, Trump has inherited his party’s ties and commitments to the rich. His platform promises such lavish tax cuts for the wealthy that it would be impossible to sustain existing social programs, let alone improve them. His appeal is not grounded in an actual mass movement but instead in the sort of post-democratic spectacle that Schafer and Streeck see as the mark of contemporary electoral politics.

In any case, unless populist left or right parties assumed power in a number of countries at the same time, the bond markets can mount a ‘credit strike’ (the contemporary equivalent of the capital strike) against any single government that seeks to abandon neoliberal constraints. Syriza is an object lesson in the power of a small government relative to the bond markets combined with international agencies. Only the U.S. government, and perhaps even not it, has the economic power to adopt signi?cant change unilaterally.

Of course, most voters, especially those motivated by nativism, do not make such complex political and structural calculations. Instead, they take self-destructive stands in an effort to lash out against alien others they believe are polluting their communities and country. Contemporary nativism can be understood, as the nineteenth century German socialist August Bebel described the anti-Semitism of his time, as the “socialism of fools.” Thus, the Brexit vote, which was won with the self-destructive support of Welsh and English voters in communities with the heaviest EU subsidies is a spectacular manifestation of often inchoate anger at elites, in this case the unelected men and women who make EU policy and have imposed austerity and appear to be unable or unwilling to stem emigration from the Middle East and North Africa. Although most non-white immigrants to Britain come from the former colonies, and are not enabled in any way by Schengen, Brexit voters thought leaving the EU would restore Britain’s white identity. Similarly, if Trump were to become president, coal and manufacturing jobs would not return to the U.S. but his supporters would have a leader giving voice to their racist notions from the most prominent governmental of?ce in the world.

Racism has a long history in the United States, Britain, France, and elsewhere. Its virulence and endurance are a joint project of ignorant and angry masses and elites that engage in race baiting or immigrant baiting to win popular support for pro-capitalist and neoliberal parties and platforms. Trump is the nominee of the political party that has made racial appeals for the past fifty years. Nixon’s law and order platform was directed as much against the civil rights movement as against actual street crime and certainly was understood that way by his supporters. Later Republicans made barely veiled racist appeals as they fulminated against “strong young bucks” collecting welfare (Reagan) and broadcast commercials depicting black men walking out of prisons and raping white women (George H. W. Bush). The French National Front shares a base and history with the pied noirs who fought against Algerian independence and carried their contempt for North Africans to the present. The Brexit leaders come out of the right wing of the Conservative party which, under Thatcher, blamed Britain’s (relatively low) crime rate on non-white immigrants and sought to restrict future immigration.

Elites that seek to win majorities for policies that bene?t the upper crust by patronizing politicians who make nativist and racist appeals have been able to play and win this cynical game for decades. The people actually elected to of?ce, like Reagan, Thatcher, Sarkozy, and the Bushes, kept racist sentiments under control and obediently pursued neoliberal policies. However, the masses have grown dissatis?ed with symbolic acknowledgements. Falling living standards and discontent with the changing conditions of their societies, a discontent cultivated and heightened by the veiled racism of conservative politicians, have produced the current level of anger.

Masses lash out in ways that can potentially harm elites. Thus, the London financiers supported racist Conservative politicians and funded the jingoist and dishonest Murdoch media outlets, and now with Brexit they could find their privileged access to the Continent severed and their ability to act as the financial haven (and money launderer) for the world undermined. If Trump were to win, it would be because most career Republican politicians, funded for decades by elite financiers and corporations, pretended that he was just a normal candidate. A Trump presidency could disrupt global markets, cause a stock market crash, and unleash popular anger and vigilantism that Trump, the Republican Party, and elites would be unable to control. We need to remember that Hitler never won a majority. He was placed in power by normal conservative German parties that thought they could control him and his followers.

Will mass anger at elites get worse? Two factors make it seem likely that the current upsurge in left and right populism will strengthen. First, neoliberalism remains the guiding philosophy for elites and for the governments they control. And neoliberalism is likely to produce more financial collapses, which will provoke new waves of anger and lead masses to search for solutions that can point as easily toward racial scapegoating as to systematic reform directed from the left.

Second, environmental crises, above all global warming, are likely to spark massive waves of migration from countries that are running out of water, enduring droughts or flooding, or which are no longer able to produce food as climate changes. Yemen, with a population of 24 million, is slated to become the first country on Earth to run out of water, due to lack of rainfall and the pumping of their aquifers, within twenty years, i.e. by 2034 (Lichtenthaeler. 2014). Environmental catastrophe in that one country will more than double the number of refugees in the world. Coastal flooding will create tens of millions of refugees elsewhere, most notably in Bangladesh, a country of 156 million that will lose up to 17% of its land mass by the end of this century as sea levels rise due to global warming, creating another 20-30 million refugees from that one country alone. Worldwide there could be 250 million refugees, a majority internal but still up to 100 million crossing borders, due to global warming by 2050. Already there are backlashes against large-scale migration throughout the world. The numbers of migrants due to environmental disasters will be on a scale never before seen, and therefore will provoke much greater opposition than already exists toward refugees.

Anti-immigrant movements are couched in nationalist terms, and thus environmental refugees will spur nationalism in receiving countries. Nationalist politicians will bene?t from anti-immigrant passions to an even greater extent than they already have. But then mass supporters will expect the nationalist politicians they elected to actually cut the ?ow of immigrants. At the same time, there will be demand for governments to secure resources abroad, to guard domestic resources at the expense of foreigners, and to mitigate the effects of global warming such as coastal flooding, drought, and other forms of severe weather.

Mitigation of environmental disasters will cost a vast amount of money, as does blocking immigrants and securing resources. As I noted earlier, racist demagogues like Trump and Le Pen suggest they will preserve or increase social bene?ts for ‘real’ citizens. Those tasks cannot be accomplished as long as neoliberal budget cutting and low taxes on the rich endure. If such politicians are elected to of?ce, they could repudiate these promises, or refuse to address the effects of global warming in any way. Alternately, they could try and fail to address those issues because they are unwilling to raise taxes or because they and their associates are just incompetent to administer programs on such a vast scale. If that is the outcome, then mass anger at elites and at immigrants and minority groups could intensify and remain unrequited by governmental action. This is a recipe for greater political turmoil, vigilante violence, and the development of neo-fascist mass parties with clearer ideological commitments to racial nationalism. We know the end point of such a politics.

Alternately, leftists, who are willing to confront elites and who do have clear plans for social programs and governmental action, could win future elections. Then mass anger at elites would be resolved because elite power and privilege would be diminished. This is a much more hopeful path. Elites with their vast resources, high levels of organization, and control over media outlets, can play a decisive role in determining which outcome prevails. No doubt, they hope to continue to muddle along and not have to choose between racist authoritarianism and leftist reform by maintaining neoliberal governments that increasingly fail to address mass needs and desires and therefore are becoming every more discredited. However, sooner or later, masses will decisively reject the narrow and unsatisfactory political choices offered to them by elites. Global warming certainly will deepen if not hasten this moment of crisis.

If (and when and where) the left comes to power, elites will pay more in taxes and higher wages. However, elites will continue to enjoy the privilege of living in liberal democracies and will know that their descendants will be protected from environmental catastrophes. However, if elites continue to actively or passively encourage the racist demagogues of the right, they will live in societies that are fundamentally transformed beyond their control. Where unpredictable authoritarian leaders take power, elites can lose their liberties and ultimately even their wealth. As Marx put it about a similar elite choice 160 years ago in The Eighteenth Brumaire, “out of enthusiasm for its moneybags it [the bourgeoisie] rebelled against its own politicians and literary men; its politicians and literary men are swept aside, but its moneybag is being plundered now that its mouth has been gagged and its pen broken” ([1852] 1937, p. 60).

Fortunately, in the end the choices will be made by masses and not elites, and they are much more likely to choose a humane non-racist future than are the elites who have exercised almost unchallenged political and economic control for the past forty years.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai International Discussion Club

- Bourdieu, Pierre. [2001] 2003. Firing Back: Against the Tyranny of the Market 2. New York: New Press.

- Castells, Manuel. 2011. “The Crisis of Global Capitalism: Toward a New Economic Culture?” pp. 185–209 in Calhoun, Craig and Georgi Derluguian, eds. Business as Usual: The Roots of the Global Financial Meltdown New York: NYU Press.

- Krippner, Greta. 2011. Capitalizing on Crisis: The Political Origins of the Rise of Finance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lichtenthaeler, Gerhard. 2014. “Water Con?ict and Cooperation in Yemen.” Middle East Research and Information Project #254. www.merip.org/mer/mer254/water-con? ict-cooperation-yemen

- Marx, Karl. [1852] 1937. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2013. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Schafer, Armin and Wolfgang Streeck. 2013. “Introduction: Politics in the Age of Austerity.” Pp. 1–25 in Politics in the Age of Austerity, edited by Schafer, Armin and Wolfgang Streeck. Cambridge: Polity.

- Summers, Lawrence. 2016. “What’s behind the revolt against global integration?” in The Washington Post, April 10. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/whats-behind-the-revoltagainst-global-integration/2016/04/10/b4c09cb6-fdbb-11e5-80e4-c381214de1a3_story.html