Executive Summary

Russia’s Far East and Siberia have much in common with Australia in terms of geopolitical, geo-economic, and even sociopolitical characteristics. However, Russia–Australia economic cooperation has been showing a downward trend over the last decade. The two countries failed to realize the cooperation potential opened by the end of the Cold War. The major barriers to the bilateral cooperation are exogenous to the relationship itself. On the Australian side, the significant systemic barrier to cooperation with Russia in the Far East and beyond is Australia’s deep embeddedness in the American security structures, high responsiveness to Washington’s interests, and lack of independence in foreign policy decisions. As a result, Australia–Russia relations have become residuals of US–Russia and EU–Russia relations and are increasingly subject to the character of interaction between Moscow and Washington or Moscow and Brussels. On the Russian side, increasingly assertive and at times aggressive foreign policy as well as political activity in the South Pacific island states have contributed to the deterioration of relations with Canberra. While cooperation opportunities in Russia’s Far East exist, predominantly in the mining industry, the current sanctions regime against Russia, of which Australia is a part, seriously undermines the prospects of cooperation both directly – by creating barriers for Australian investors – and indirectly – by complicating the political climate surrounding Russia–Australia relations.

Development of the Russian Far East: Implications for Australia

Even though Russia’s eastern territories, including the Far East and Siberia, and Australia are worlds apart on the map, they may not be so in terms of geopolitical, geo-economic, and even sociopolitical attributes that have shaped, though to different extents, the development of both throughout centuries. Geographical remoteness of the administrative centres and the traditional refusal to hold far-off authorities in awe, low population density and the abundance of land, economic models primarily based on resource extraction, as well as the shared past of being penal colonies[1] – all are the features shared by both Australia and Russia’s Siberia and the Far East.

However, similarities in natural endowments and historical trajectories have not transmuted into productive cooperation or at least effective learning from each other’s development experience.[2] Interaction and cooperation between Australia and Russia have at best been patchy. The friendly beginning after the first acquaintance in the early 19th century was followed by antagonism in the second half of the century; alignment during World War I was later succeeded by the disruption of diplomatic relations after the Russian 1917 Revolution. Then again, shortly after World War II made USSR and Australia de facto allies, the Cold War placed the two countries in the rivalling military.political blocks, which resulted in complete interruption of diplomatic ties in the early 1950s. Despite the slight ‘warming up’ in USSR–Australia relations in the 1970s under the Labour government of Gough Whitlam in Australia, the general atmosphere of mistrust and suspicion continued to plague the relationship, frustrating economic cooperation and keeping bilateral trade at miniscule volumes.

The collapse of the USSR and the ensuing fundamental political and economic changes in Russia opened the gates for new cooperation. Mutual perceptions improved dramatically. In 1997, in the context of post-Cold War political rapprochement, the official Australian view of Russia was relatively positive and emphasising the Asia-Pacific future of Russia. Thus, according to the 1997 Australia’s Foreign and Trade Policy White Paper, Russia’s attention in the short term was likely to be predominantly concentrated on the West, which implied that Russia was unlikely to be turning into an Asia-Paci. c power with significant regional impact. However, in the medium to long term ‘Russia must be seen as a significant country in the Asia-Pacific’.[3] Moreover, ‘as Russia puts its economic house in order, its interests in its Pacific seaboard will increase, potentially to the advantage of Australia’s trade and investment interests.’

The Australian government also pledged to ‘encourage Russia’s constructive role in Asia-Pacific affairs, recognising that Russia will continue to operate at a global level, and that an East Asian focus could help lock in Russia’s economic transition. The working out of Russia’s longer-term relations, not only with the US but also with China, Japan, and India, will be important for the security of the Asia-Pacific.’[4] This positive assessment was reinforced by the 2003 Australia’s Foreign and Trade Policy White Paper, which stated that:

Russia could become a more important partner for us. Its transformation from a centrally planned to a market-based economy, integrated into the global economy, will be a complex and gradual process. But dependence on foreign markets, capital, and technology, and its aspirations to join the World Trade Organization (WTO), will drive Russia’s increased international economic engagement. Australia is a potentially valuable economic partner as Russia looks for assistance to develop its vast natural resources.[5]

Russia was reciprocating by speaking highly of Russia–Australia relations and by trying to strengthen contacts with Australia’s political elites. President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Australia in September 2007, and later President Dmitry Medvedev’s meetings with Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in November 2008 and April 2009, helped to intensify bilateral political dialogue. Russia’s former ambassador to Australia Alexander Blokhin stated in 2009 that ‘the level of the relationship between the two countries that has been achieved over the past three years has never been so high.’[6]

In an article, published in the Australian Journal of International Affairs (a major Australian journal in the field of international relations) in 2012 and commemorating the 70th anniversary of establishing diplomatic relations between Russia and Australia, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov praised multiple international formats and mechanisms of Russia–Australia interaction. These include the Russia–Australia Joint Commission on Trade and Economic Cooperation, comprising of working groups on cooperation in agriculture, mining, trade and investment, and peaceful uses of nuclear energy, the forum of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM), ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), and ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting with dialogue partners (ADMM-Plus). Lavrov also emphasised the importance of focusing on the APR of which Russia ‘is an integral part’. Special attention, thus, should be paid to the ‘seamless integration […] into the system of regional economic relations and the use of unique sources of growth existing in the Asia-Pacific region for the innovation-based development of the national economy, primarily in relation to Siberia and the Far East.’[7] In the context of Russia’s re-orientation to the East, the progress that has been achieved between the two countries was claimed to ‘offer encouraging prospects for a higher level of Russian-Australian relations’ and generate ‘the necessary preconditions for the further development of cooperation between Russia and Australia’.[8]

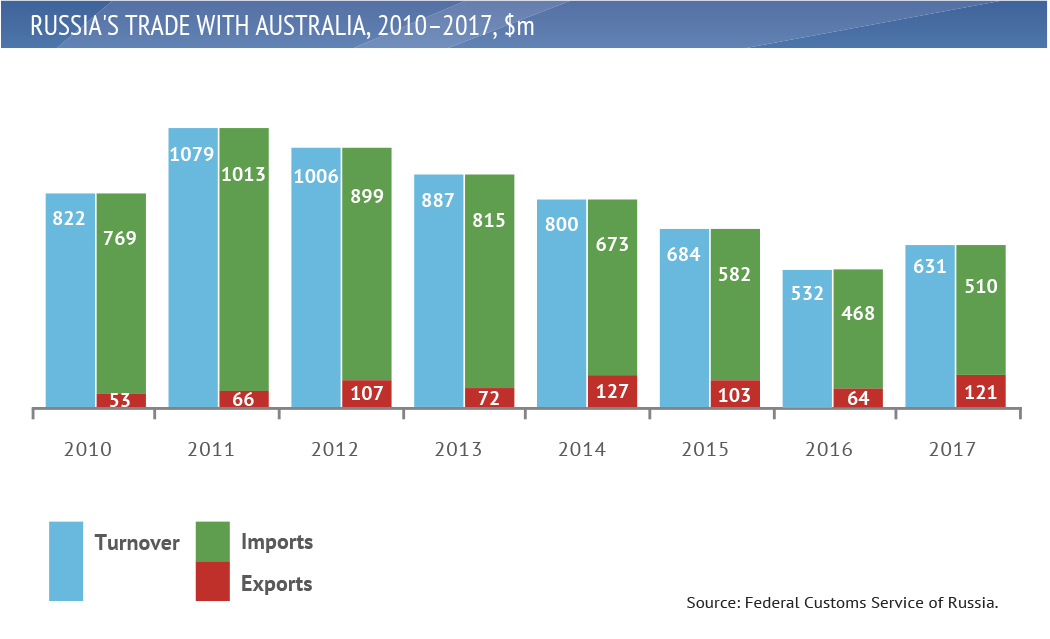

However, economic cooperation, while showing some signs of improvement, never truly picked up. The bilateral trade turnout remained very modest compared to Russia’s and Australia’s trade with most of the other Asia-Pacific countries. Moreover, after having reached its historical peak of less than $1.1bn in 2011, the bilateral trade volume started to plummet, falling below the levels of the late Cold War period. Similarly, in the sphere of foreign direct investments, an unstable upward trend was followed by negative dynamics. Russian foreign direct investment in Australia, after having exceeded $1.2bn in 2013, dropped to $431m in 2014 and further to less than $200m in 2016. The same applies to Australian investments in Russia, which had been growing from $50m to $65m between 2010 and 2013 but then fell to $62m in 2014.[9]

Despite the fact that the volume of investments was rather modest, there were some projects significant for Russia’s Far East and Siberia. The major Australian investors in Russia were mining companies, such as BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, whereas the principal Russian investors in Australia were Rusal, Norilsk Nickel, Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works (MMK), Sberbank, and Vneshtorgbank (VTB). In 2006, Norilsk Nickel concluded deals with Australian BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto to conduct minerals exploration and development in Russia. A year earlier, Rusal actively invested in the Australian mining industry and acquired a share in Queensland Alumina.

Particularly remarkable was the signing between Canberra and Moscow on September 7, 2007, of the Agreement on Cooperation in the Use of Nuclear Energy for Peaceful Purposes. According to the agreement, Russia could enrich Australian uranium for use in its civil nuclear power industry. The deal was worthy of $1bn, and both sides were interested in the agreement.After significant delays, triggered by Canberra’s indignation about the Russia–Georgia war and the recognition of independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia by Russia, as well as domestic political resistance in Australia, mostly emanating from the Australian Greens but also from the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties (JSCOT), the deal was eventually ratified and entered into force in November 2010. However, following the Ukrainian crisis and the introduction of sanctions and travel bans against Russia, on September 3, 2014, Prime Minister Anthony Abbott announced the suspension of Australian uranium sales to Russia ‘until further notice’.[10]

In summary, the nascent cooperation between post-Soviet Russia and Australia could not sustain the trial by political factors. Both Canberra and Moscow failed to take advantage of the opportunities that had opened after the collapse of the USSR to develop economic relations strong enough to endure the impact of political crises. The progress that the two countries had achieved in the late 1990s – early 2000s was essentially nullified. The Joint Commission on Trade and Economic Cooperation suspended its activities. The same was the case with the major Russian companies, such as Norilsk Nickel, that also gradually curtailed their business in Australia. According to Russian Ambassador in Australia Vladimir Morozov, the conditions for doing business in Australia for the Russian companies became ‘not always comfortable’, whereas ‘tense political relations and sanctions had played a definitely negative role’.[11]

While there is still anticipation of possibilities in cooperation with Russia, especially in the context of Russia’s re-orientation to the APR, it can be argued that Russia–Australia relations are not self-sufficient and are heavily affected by factors that are exogenous to them. Under the current political circumstances, the efforts of Russia to increase its presence in Asia is perceived in Canberra as having serious ‘implications’ rather than ‘opportunities’ for Australia.[12]

The Evolution of Russia– Australia Relations

Overall, Russia–Australia cooperation has deteriorated since 2012. There are several causal factors behind this outcome. The most fundamental one is that the level and nature of cooperation between the two countries is subordinate to Russia’s relations with other Western nations, predominantly the US and the UK. Thus, in the 19th century, the tensions between Australia and Russia intensified because of the deterioration of Russia–Britain relations. Subsequently, Australia–Russia relations improved as a result of Russia–Britain rapprochement. In today’s world, the quality of interactions between Moscow and Canberra to a considerable extent depends on Moscow–Washington relations. In other words, Australia has limits in its foreign policy, and its actions with regard to most of the international issues are reflective of the preferences of its more powerful allies. Dependency on allies, such as the US and UK, in foreign policy making generates an important milieu in which Australia’s relations with Russia evolve.

In this context, the chain of events surrounding the 2008 Russia– Georgia war and the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, as well as Russia’s increasingly assertive foreign policy, severely undermined the prospects of Australia– Russia cooperation in Russia’s Far East or elsewhere. Standing by its allies is the cornerstone of Canberra’s foreign policy. The passage of the above.mentioned uranium deal in the Australian parliament was stonewalled by the reaction to the Russia–Georgia confrontation. Canberra stood against the recognition of Abkhazia and Ossetia by Moscow. In an interview to Sky News, the then Australian Foreign Minister, Stephen Smith, emphasised that while Russia is ‘very keen to pursue or proceed with the agreement’, Australia will also ‘consider the state of our bilateral relations with Russia and Russia’s recent conduct in Georgia and Abkhazia and South Ossetia’.[13] Two years later, in March 2010, Australian officials allocated AUD 1m to help Georgia recover from the Russian intervention, reinforcing the image of Russia as an external threat.

This perception only grew stronger as the battle for broader international recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia moved to the South Pacific – an area where Australia has long enjoyed close economic and political ties. The recognition of the independence of Georgia’s breakaway republics by Nauru, Vanuatu, and Tuvalu as a result of Moscow’s ‘checkbook diplomacy’ in the region caused worries in Canberra about Russian threat. Australia accused Moscow of pushing tiny Pacific island countries towards accepting the independence of the disputed territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. According to the accusations, Moscow promised tens of millions of dollars of aid to Nauru, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu in exchange for the recognition. According to the Australian Parliamentary Secretary for Pacific Island Affairs in the federal government, Richard Marles, ‘what we are seeing here is really the exploitation of one of the smallest countries in the world’. While, according to Marles, Australia did not regard the Pacific as its exclusive patch, other countries should be transparent with aid.[14]

Among other factors that contributed to the negative attitude of the Australian policy-making elites towards Russia prior to the Ukrainian crisis were Moscow’s policies in Syria and the alleged support of Bashar al-Assad, Russian border guards’ arrest of Australian activist Colin Russel who, together with other Greenpeace activists, protested against off-shore oil drilling in the Pechora sea in September 2012, Russia’s ‘gay propaganda’ law, which was vociferously criticized by the Greens in Australia, and, most importantly, a growing perception in Canberra that Russia is becoming one of the US’ actual rivals. The latter is of crucial importance, and it fully manifested itself during another major crisis in the post-Soviet space – the 2014 Ukrainian crisis.

Soon after the cessation of Crimea from Ukraine, Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop announced targeted economic sanctions as well as travel bans against Russian individuals who, according to Canberra, contributed to the encroachment on Ukraine’s sovereignty. Worth noting is that in her speech in the House of Representatives on March 19, 2014, Bishop emphasised that: ‘Australia’s response to Russia’s actions is aligned with the action taken by the EU, the US, and Canada, who have also implemented a number of targeted sanctions and travel bans. Measures have been taken in close coordination with our friends and allies, including the US, the UK, Canada, and Japan.’[15]

In the following few months, Australia substantially extended anti-Russian economic sanctions and travel bans. The bilateral relationship further deteriorated after the downing of the Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 with 38 Australian citizens onboard over Eastern Ukraine on July 17, 2014. The then Prime Minister of Australia, Anthony Abbot, in his statement to the Parliament stressed that ‘MH17 had been shot down by Russian-backed rebels over Eastern Ukraine. This was not just a tragedy; it was an atrocity.’[16] A crucial factor in Australia’s stance towards Russia is its solidarity with the West. On September

1, 2014, Prime Minister Abbot further stated: ‘I inform the House that Australia will raise its sanctions against Russia to the level of the European Union’s. There will be no new arms exports; there will be no new access by Russian state-owned banks to the Australian capital market; there will be no new exports for use in the oil and gas industry; there will be no new trade or investment in Crimea; and there will be further targeted financial sanctions and travel bans against specific individuals.’[17]

On November 14, 2014, Australian Ambassador to Russia Paul Myler in his interview to Interfax emphasised that in terms of anti-Russian sanctions ‘we followed exactly the same progression as the EU’.[18] In the same interview, responding to a question concerning Australian businessmen’s interest in cooperating with Russian companies, Myler said that a lot of Australian companies now choose ‘to commit their capital to other markets because they are uncomfortable with the risks associated with Russia at the moment. Russia was really a good market and had a lot of potential. Russia has huge deposits, huge reserves of everything essential, and there was going to be really good cooperation. But now I think the risks associated with Russia are starting to have little more limitation on the purely commercial decision about where you invest with your company.’[19] In September 2017, the Australian government extended the previously imposed sanctions to include 153 individuals and 48 companies in the sanctions list. Among those targeted by sanctions are Sberbank, VTB Bank, Vnesheconombank, Gazprombank, Gazprom Neft, Rosneft, Transneft, Oboronprom, United Aircraft Corporation, etc.

In summary, Australia’s embeddedness in security alliance with the US, its unconditional solidarity with the American and European interests, as well as Russia’s assertive foreign policies in the post-Soviet space and elsewhere, including activities in the South Pacific, pose severe barriers to the development of Russia–Australia cooperation, including in Russia’s Far East.

The Current Challenges for Cooperation Between Australia and the Russian Far East

Australia’s cooperation with Russia’s Far East, and Russia as a whole, are severely affected by the broader political context and Russia’s relations with the US and the EU. In the context of Russia’s re-orientation to the Asia-Pacific, Australia has a potential to become a valuable partner. However, this is not going to be an easy task. Because of unfavourable political climate, there is no significant interdependence in Australia– Russia economic or political relations. While the immediate threat (either political or military) to Australia emanating from Russia is not significant, Canberra views Russia’s increasing presence in the APR and the modernization of Russia’s Pacific fleet mainly through negative rather than positive lenses.

At the same time, the fact that both Australia and Russia are exporters of energy resources (with Australia announcing plans to become the world’s biggest LNG exporter), there are reasons to expect Australia– Russia competition for the energy markets of China, India, and other Asian countries. This is exacerbated by Australia’s growing concerns about foreign policy intentions of China, with which Russia has close economic, political, and strategic ties. In this context, Moscow’s close cooperation with Beijing is likely to be viewed in Canberra as a factor contributing to the deterioration of Australia–Russia relations. While economic cooperation between the two countries in Russia’s Far East is not impossible, it is likely to be an exception rather than a rule, at least in the short to medium term. Australia tends to follow the US and the EU in its foreign policy decisions towards Russia. Therefore, a possible improvement of Russia’s relationship with either the US or Europe is likely to contribute to strengthening of Australia–Russia economic ties.

Conclusion. Opportunities for the Enhancement of Bilateral Trade and Economic Relations

Of particular interest to potential Australian investors is the mining sector of Russia’s Far East and Siberia. Australia recognises Russia as the largest producer of mining commodities, such as bauxite, coal, copper, diamond, gold, iron ore, lead, nickel, potash, silver, uranium, etc. in the world. Due to the weakness of rouble, Russia’s coal output is likely to grow substantially, with Russian mining companies developing new deposits. The major mining regions in Russia are the Far East, Eastern Siberia, and the Kola Peninsula. Many of these resources remain untapped and will require modern technologies and investment. This sector opens opportunities for Russia–Australia cooperation.

Due to Russia’s vast territory and other geographic parameters, Russian mining companies are interested in optimizing the costs of operation and increasing efficiency of development projects.As Russia’s mining sector is looking for cooperation with foreign companies to obtain access to new technologies and products, new opportunities may open for Australian exporters. According to the Australian Trade and Investment Commission, the key opportunities for the Australian mining companies in Russia’s Far East may include the areas in which Australian suppliers have a competitive advantage, such as mapping, airborne surveying, prospecting, exploration drilling services; EPC and engineering, procurement and construction management (EPCM) services for the mining projects with the capacity of one–five million tons of ore per year; mining optimization consulting services; mining training services; mining and processing equipment and technologies; maintenance and repair services for mining equipment; IT, geological data analysis and data modelling; engineering, project management, risk analysis and other consulting services; mine safety, audit and environmental services; ore processing and screening; geotechnical and construction services.[20] Australian mining equipment, technology, and services companies have a good reputation within the Russian mining industry, which opens multiple opportunities for cooperation.

At the conference MINEX Far East 2017, which took place in Magadan, Russia, on July 5–6, 2017, the Australian Honorary Consul and Trade Representative in Russia’s Far East, Vladimir Gorokhov, emphasised that the Australian Trade and Investment Commission sees a great potential in developing cooperation between Russian and Australian companies in Russia’s Far East.[21] An example of recent successful cooperation in the region is the partnership between the Australian coal company Tigers Realm Coal and its Russian partner, Northern Paci. c Coal Company, that are jointly developing the Amaam coking coal .eld in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. Tigers Realm Coal is a resident of the TOR Beringovsky. The extracted coal is exported to China, Japan, and South Korea.[22]

At the same time, the sanctions regime requires that the Australian companies with existing business activities in Russia should register on the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Online Sanctions Administration System, to submit an enquiry in relation to whether they need a sanctions permit for an activity or a formal application for a sanctions permit.[23] The current condition of Australia–Russia political relations is a barrier to the progressive development of economic ties.

Valdai International Discussion Club

[1] For an elaboration of these similarities from a cultural perspective, see: Andrews, H, 2015, ‘Siberia’s Surpris.ingly Australian Past’, Quadrant, no. 59.6, p. 30-33.

[2] It is still a valid analytical question of why, having been endowed with comparable initial parameters, Aus.tralia and Russia’s Far East/Siberia ended up very differently in terms of socioeconomic development.

[3] ‘In the National Interest: Australia’s Foreign and Trade Policy White Paper’, 1997, Commonwealth of Australia: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, p. 31.

[4] Ibid.

[5] ‘Advancing the National Interest: Australia’s Foreign and Trade Policy White Paper’, 2003, Commonwealth of Australia: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, p. 31.

[6] ‘Prazdnovanie Dnya Rossii v Brisbene’ [Russia Day Celebration in Brisbane], 2009, Edinenie, July 6. Available from: http://www.unification.com.au/articles/read/203/.

[7] Lavrov, SV, 2012, ‘Comprehensive Strengthening of Cooperation: For the 70th Anniversary of Diplomatic Re.lations between the Russian Federation and Australia’, Australian Journal of International Affairs, no. 66.5, p. 623-624.

[8] Ibid, p. 625.

[9] Data on investments comes from the ‘Foreign Direct Investments in Russia by Instruments and Investors, 2010– 2014’, Central Bank of the Russian Federation (Available from: http://cbr.ru/statistics/print.aspx?file=credit_ statistics/dir-inv_in_country.Htm) and ‘International Investments Australia 2016’, the Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2017 (Available from: http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Docu.ments/international-investment-australia.pdf )

[10] ‘Australia-Russia Nuclear Cooperation Agreement Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ )’, 2014, Australian Gov.ernment: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, November 14. Available from: https://dfat.gov.au/geo/russia/ Pages/australia-russia-nuclear-cooperation-agreement-frequently-asked-questions-faq.aspx#16

[11] ‘Posol RF v Avstralii: My Gotovy Obsuzhdat’ Vozobnovlenie Sotrydnichestva [Russian Ambassador in Australia: We are Ready to Discuss the Resumption of Cooperation], 2015, RIA, February 5. Available from: https://ria.ru/ interview/20150205/1046028585.html

[12] See, for example, Fortescue, S, 2017, ‘Russia’s Activities and Strategies in the Asia-Pacific, and the Implica.tions for Australia’, Parliament of Australia: Department of Parliamentary Services, March 23.

[13] ‘Interview with Kieran Gilbert’, 2008, The Hon Stephen Smith MP: Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Sky News, November 25. Available from: https://foreignminister.gov.au/transcripts/2008/081125_sky. html

[14] Flitton, D, 2011, ‘Australia Lashes Russia over Aid’, The Sydney Morning Herald, October 17. Available from: https://www.smh.com.au/national/australia-lashes-russia-over-aid-20111016-1lrjv.html

[15] ‘Commonwealth of Australia Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, Official Hansard No. 4’, 2014, March 19, p. 2447. Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary _Business/Hansard

[16] ‘Commonwealth of Australia Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, Official Hansard No. 13’, 2014, August 26, p. 8549. Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary _Business/Hansard

[17] Ibid.

[18] ‘Paul Myler: We are Going to See Some Changes in Russia’s Food Policy by February–March’, 2014, Interfax, November 14. Available from: http://www.interfax.com/interview.asp?id=550848.

[19] Ibid.

[20] ‘Mining to Russia: Trends and Opportunities’, Australian Government: Australian Trade and Investment Com.mission. Available from: https://www.austrade.gov.au/australian/export/export-markets/countries/russia/in.dustries/Mining

[21] ‘Avstraliiskie Biznesmeny Izuchayut Investitsionnye Vozmozhnosti Magadanskoy Oblasti’ [Australian Busi.nessmen Explore Investment Opportunities in Magadan Oblast], 2017, Kolyma.Ru, July 5. Available from: http:// www.kolyma.ru/index.php?newsid=68463

[22] ‘Bering Coal Basin: Amaam and Amaam North, Chukotka, Far East Russia’, Tigers Realm Coal. Available from: http://www.tigersrealmcoal.com/projects/

[23] ‘Market profile – Russia’, Australian Government: Australian Trade and Investment Commission. Available from: https://www.austrade.gov.au/Australian/Export/Export-markets/Countries/Russia/Market-profile