The 21st century began with chaos in international relations, the growing multipolarity of the once unipolar world, and geographic determinism giving prominence to regional leaders, who are resisting unipolar projects and competing with each other in their geographical region. However, nation states have shown that they are still to be reckoned with.

International organizations and transnational law enforcement agencies, which were created to ?ght transnational threats such as international terrorism, drug cartels and criminal organizations, have not increased their ef?ciency. Nation states continue to shoulder the biggest burden of fighting the above threats.

Globalization has stimulated integration and accelerated various global processes, but it has not made this world safer or more stable. The connection between national, regional and global security is growing stronger. The fact that transnational threats operate as a network has highlighted the importance of interaction between nation states in fighting these threats. But strained relations between the geopolitical power centers, contradictions between regional states and the revival of bloc mentality are hindering the civilized world from consolidating its resources.

The period of unipolar world witnessed many serious violations of international law, which the reviving states have copied. This, in turn, has led to new con?icts and wars. The ideology of the states that see themselves as the winners of the Cold War has failed to become dominant in the world; the liberal intervention has failed. The ongoing processes in the West have discredited the path chosen by these states. The democratic principle of the free expression of will has come into con?ict with global integration. The views of the political and economic elites in the West have clashed with the views of the people. The results of the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump have showed the victory of protectionism ideas. The predominance of liberal ideas has been challenged not by the states as a target group of liberal interventionists but by the people of these same Western states.

At a time when international law is losing its value and is often interpreted very loosely, nation states endeavor to follow a pragmatic policy based on national interests. This casts a bright light on a discrepancy between the theory of international relations and reality. The global power centers are abandoning the ideological view on foreign policy in favor of pragmatism and result. The economic and financial crises, the use of sanctions in international relations, and the weakening of integration increased the number of con?icts and wars and open interventions in the internal affairs of states. This has shifted the focus on the objective perception of national interests by states that have become the objects of pressure and the relation of these national interests to history, geography, economic expediency and reality.

Western academicians for a long time refused to recognize the importance of national identity in foreign policy, focusing instead on the paradigms of realism and neoliberalism in the foreign policy concepts of large and strong powers and disregarding the role of small and weak states. According to them small and weak countries have limited choice in the area of foreign policy and depend on external factors and lineups of forces. This approach is based exclusively on material values and excludes the role of social values and national identity.

The role of national identity has been objectively assessed and presented in the constructivist theory of international relations. By comprehending the national identity you can understand the conceptual basis of decisions that often clash with the geopolitical projects of large and strong powers.

Thereby, each country has a unique geopolitical identity or geopolitical code, according to the adepts of constructivism such as Gertjan Dijkink, professor of political and cultural geography at the University of Amsterdam, who is known for his works in geography, geopolitics, culturology and geographical identity. Another advocate of constructivism, Professor Colin Flint from the University of Illinois pointed out that academic and expert communities are used to old notions, paradigms and dogmas of geopolitics or the strategies of “classical geopolitical scholars.” This interpretation of geopolitics, which does not recognize the geopolitical codes of various actors of international relations, precludes an objective view on the world. The geopolitical code or identification is composed of a combination of society’s views on its geography, history, cultural and civilizational identity, and the like.

The Geopolitical Identity of Azerbaijan

In 2016, the Republic of Azerbaijan marked 25 years since the restoration of its state independence. It was a difficult period for Azerbaijan, just as for the other post-Soviet republics. The Armenia-Azerbaijan Nagorno-Karabakh conflict which resulted in occupation of 20% of Azerbaijan territory (the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Area plus 7 adjacent regions) and in one million refugees and internally displaced persons, has become the biggest foreign policy challenges for Azerbaijan. Internal instability and three presidents in two years led to the establishment of an armed opposition and pushed the republic to the brink of a civil war. The destruction of cooperation ties in the post-Soviet space endangered the production cycle and complicated the search for new markets for Azerbaijan’s products. The oil sector needed multibillion investments, which was impossible amid the war and internal instability.

However,Azerbaijan gradually overcame the problems of the early 1990s and regained the role of a regional leader in the South Caucasus. The main condition for implementing the domestic and foreign policies is a clear understanding of one’s place in the world and the region and a correct formulation and achievement of national interests based on history, geography, cultural identi?cation and economic interests. Azerbaijan’s national leader, Heydar Aliyev, created the foundation for understanding and implementing national interests. President Ilham Aliyev successfully continues his policy, adding new elements to the domestic and foreign policies of Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan has a complex and multilayered geopolitical identity that includes geographical, historical, religious and cultural components.

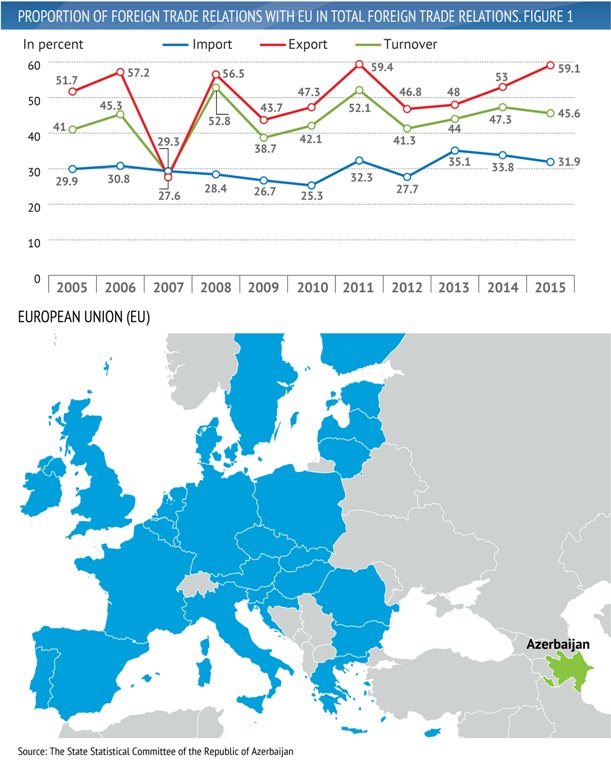

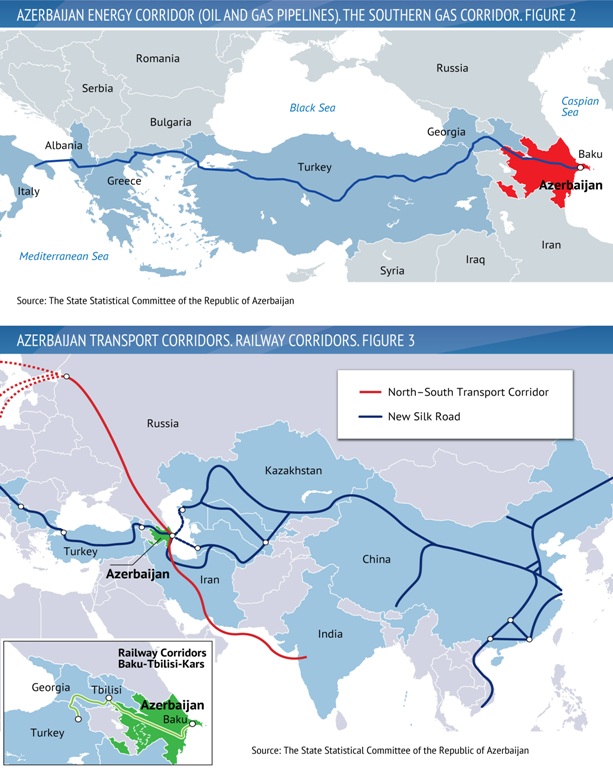

Geographically, Azerbaijan is located in Europe (Figure 1) and joined the Council of Europe in 2001. Although it decided against signing an association agreement with the EU in 2014, the EU is Azerbaijan’s biggest trade partner. It accounted for 45.6 percent of Azerbaijan’s foreign trade in 2015. Both parties are interested in promoting energy and transport cooperation. To develop mutually bene?cial and equal cooperation, the parties are holding talks on a new EU-Azerbaijan agreement to replace the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement signed in 1996. The parties are building the Southern Gas Corridor to deliver Azerbaijani gas to the EU (Figure 2) and a railway line from Baku to Kars (Turkey) via Tbilisi, Georgia (Figure 3).

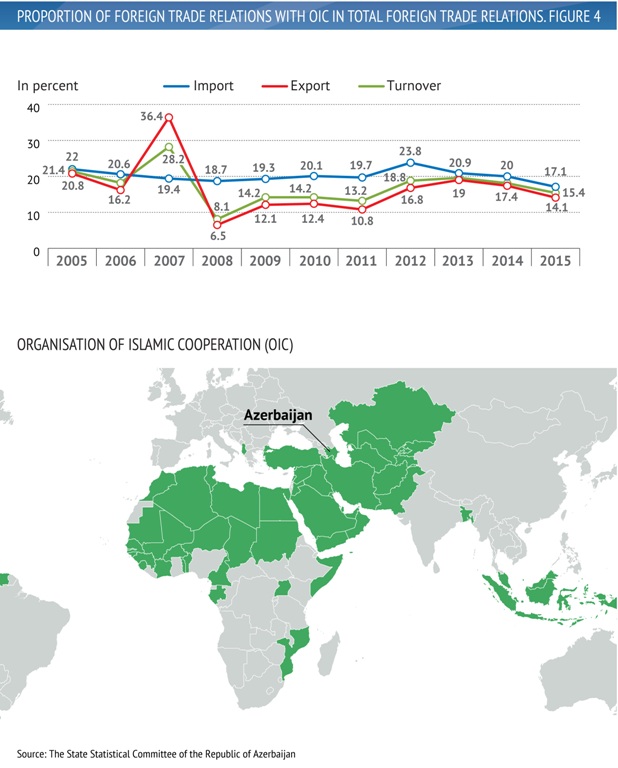

Islam is the predominant religion in Azerbaijan (Figure 4). Muslim countries differ by their geographical, military, political and economic concepts, but they are united in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), which Azerbaijan joined in 1991. It has initiated several OIC projects in education, culture and tourism. In 2017, Baku will host the Islamic Solidarity Games, which is evidence of Azerbaijan’s intention to work towards Islamic unity. The OIC supports all aspects of Azerbaijan’s foreign policy.

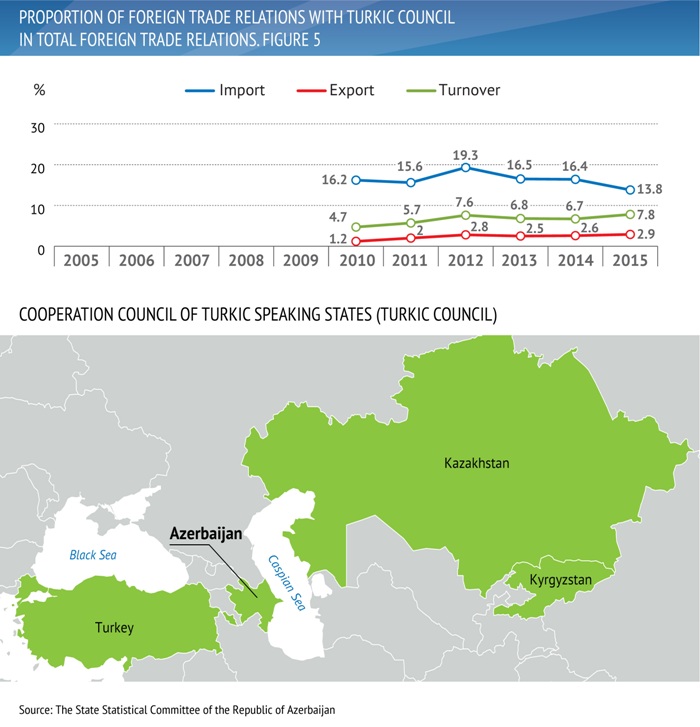

Culturally and linguistically, Azerbaijan is a part of the Turkic World (Figure 5) and as such it joined the process of Turkic integration in the 1990s. In 2009, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan met in Nakhchivan (Azerbaijan) to create the Turkic Council (the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States or CCTS). The CCTS includes countries that are also members of other economic and military political alliances. For example, Turkey is a NATO member and part of the European customs space, while Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Customs Union. Although there is a degree of confrontation among the member states of these organizations, the Turkic Council states maintain political, economic and cultural cooperation with each other. They also support Azerbaijan on the international stage, including in international organizations where the republic is not represented.

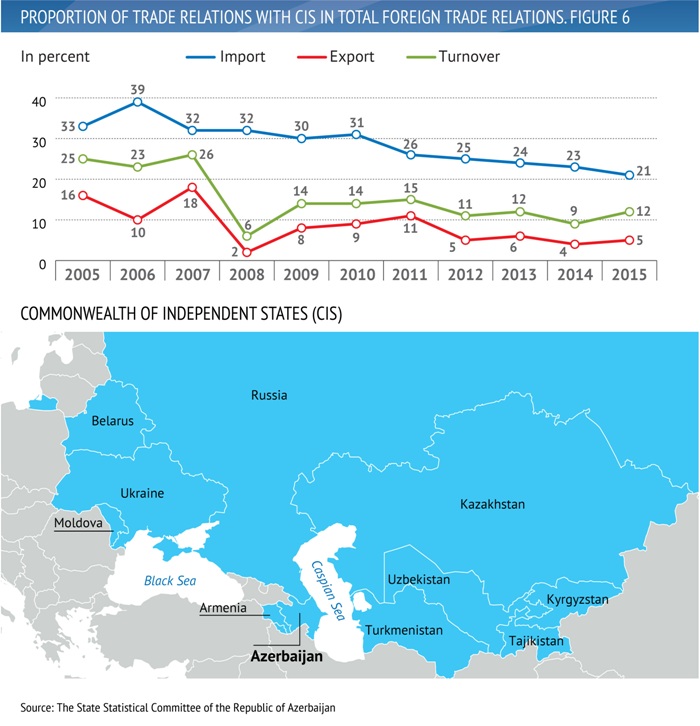

For the past 200 years, Azerbaijan was part of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union and is now a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS, Figure 6).

Azerbaijan values the CIS as a platform of political and economic interaction with the former Soviet republics. Visa-free travel and economic incentives, which go together with CIS membership, help Azerbaijan maintain stable trade and also develop mutually bene?cial military-technical and cultural cooperation with Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. The CIS countries accounted for 12 percent of Azerbaijan’s trade in 2015, most of it non-resource trade, which is strategically important and highly promising for Azerbaijan in light of low oil prices.

Thus, objectively Azerbaijan shares the same identity with many Eurasian countries, including religious, geographical, historical, cultural and linguistic identity. This is a source of many opportunities and also challenges. On the one hand,Azerbaijan is a member of many integration platforms of multifaceted geopolitical identity, such as the Council of Europe, the CIS, the OIC, the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), the Customs Union, the Black Sea Economic Cooperation Organization (BSEC), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO, status partner for dialog). On the other hand, Azerbaijan is influenced by negative processes at the above platforms.

Countries with a complex geopolitical identity must take this into account in their domestic policies. The choice of one vector of multilayer identity as the only priority in foreign policy can provoke the con?ict with other elements and result in social fragmentation and enhanced con?icts with neighboring countries.

Heydar Aliyev and his “ideology of Azerbaijanism” promoted the consolidation of society around common goals and created conditions for the development of the Azerbaijani nation based on civic nationalism. This policy focused on constructive cooperation in all spheres of geopolitical identity. The principles that have been formulated as a result are being successfully implemented by the President Ilham Aliyev.

Azerbaijan has not been and will not be an area of the global power centers’ confrontation. Geographically, it can become an area of competition for geopolitical power centers. The analysis of Azerbaijan’s position in the European, Islamic and Turkic spaces shows that Azerbaijan is holding a peripheral, border position in all these spaces and so can be viewed as a sphere of in?uence and implementation of various projects that do not always meet Azerbaijan’s national interests. Azerbaijani authorities are trying to prevent the development of conditions in which external forces could in?uence its domestic policy with a view to changing Azerbaijan’s foreign policy. Due to the country’s geographical position, this is unacceptable and counterproductive.

The next principle of Azerbaijan’s foreign policy, which stems from the above principle, is that Azerbaijan does not threaten its direct neighbors. All countries have declared this principle, but only time and experience show their compliance with it. In the past 25 years, Azerbaijan has convincingly demonstrated its commitment to cooperation with its neighbors, including when external pressure was placed on Iran over its nuclear program in 2006 and 2007 or when sanctions were introduced against Russia in 2014. In both cases, Azerbaijan resisted external pressure and even threats and refused to take steps that could damage relations with its neighbors. Azerbaijan’s membership of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which it joined in 2011, has created a favorable atmosphere in its relationships with neighboring countries, which have complicated relations with various military-political blocs and openly protest against their expansion.

Bilateral relations are a foreign policy priority for Azerbaijan, which protects them from the adverse in?uence by other countries. This principle allows Azerbaijan to cooperate with countries that have no relations between each other, to maintain regional stability and to avoid emotional reactions to the escalation of con? icts between its neighbors or strategic partners.

In other words, Azerbaijan’s foreign policy priorities include stronger bilateral ties with neighbors, equal and mutually bene?cial relations with all countries regardless of their power or size, and the implementation of economic projects. The development of the East-West and North-South vectors (Figure 3), consistent support for the principles of international law and the strengthening of national defense capability are vital elements for sovereign Azerbaijan as it is working to strengthen its international standing. This multilayered geopolitical identity helped Azerbaijan to secure the votes of 150 countries during its election as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2011. Peaceful relations with countries from different civilizations have created an atmosphere of trust and dialogue, which Azerbaijan has been working to strengthen via the World Forum on Intercultural Dialogue, the Heydar Aliyev Foundation, the Baku International Humanitarian Forum and multiculturalism policy. By reference to the speci?c features of its geopolitical identity, Azerbaijan has become a predictable state and a responsible partner, which is very important in times of global geopolitical transformations.

An objective view on all aspects of its geopolitical identity allows Azerbaijan, which is a relatively small country territorially, to pursue a constructive and pragmatic policy and to strengthen its independent position of a full member of international relations. The opportunities offered by its chosen path and the variety of instruments for implementing its foreign policy clearly show that there is no alternative to this effective and constructive approach. In the next decade, Azerbaijan will be working to achieve fundamentally different goals, including resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh con?ict with Armenia, diversifying the national economy and increasing non-resource exports, enhancing the quality of life in the country, and implementing large East-West and North-South projects. Given its multilayered geopolitical identity, Azerbaijan has the capability to achieve these goals, protect its territorial integrity and strengthen its real independence in new conditions.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.