For citation, please use:

Nikolskaya, M.V. and Matveeva, A.A., 2025. BRICS as a Brand and Its African Dimension. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(4), pp. 143–154. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-4-143-154

Of all regions of the world, Africa enjoys the widest representation in BRICS. As of summer 2025, South Africa, Egypt, and Ethiopia are full members, Nigeria and Uganda are partners, and Algeria is a partner within the New Development Bank. Over the past two years several other African states have declared their intent to become BRICS partners.

What advantages does BRICS promise for African countries? Can one speak of a real ‘African bloc’ within the group? These questions need to be answered for Russia to understand how best to cooperate with African countries, and how BRICS expansion should be directed in the future.

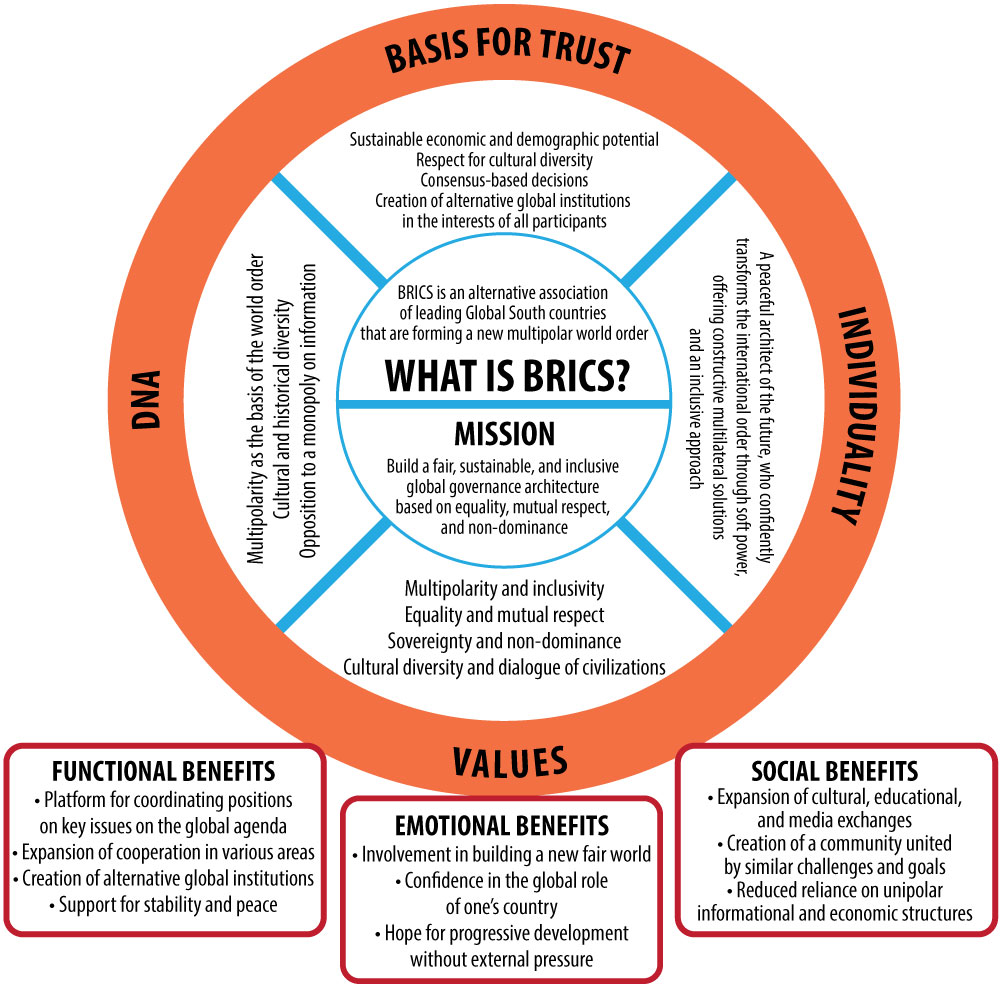

Compiled by the authors.

Counterintuitive as it may sound, a framework for analysis may be borrowed from marketing theory. Professor Stefan Tschauko of Columbia University has employed marketing theory to assess what kind of brands have been formed by international organizations, and to provide reputation-management tools for recruiting new members and obtaining political and financial support from stakeholders (Tschauko, 2025).

In this model, BRICS can be positioned as an international brand, with all the appropriate characteristics:

- DNA (a stable set of characteristics).

- Individuality (an image).

- Resources and ideological capital that create brand loyalty.

- Clear benefits for its ‘clients.’

(See Fig. 1.)

Branding theory distinguishes between three main types of benefits. Functional benefits are the practical value provided by the brand. Symbolic or emotional benefits are associated with image, status, and identity. Finally, social benefits provide a sense of belonging, support, and interaction with other ‘consumers’ of the brand or members of a specific affiliated community.

Emotional Benefits: Development, Equality, and Solidarity

A content analysis of the 2023 and 2024 BRICS summit declarations, conducted within the framework of the MGIMO project “The Role of BRICS in the World Economy and Global Economic Governance: An African Perspective,” reveals that development and cooperation are among the 700 most frequently used words.

“BRICS’[s] magnetism lies in the emotional appeal of its ideas… rooted in positive associations with investment and [in] alignment with national and global development agendas” (Papa, 2024). BRICS countries in recent years have placed inclusive growth, accounting for the interests of all nations, among their core values (Barabanov, 2025).

Within BRICS, Africa has the opportunity to end its status and image as a perpetual recipient of donor assistance, and instead emerge as a full-fledged partner. For African nations, this historical closure means dignity and respect for interests long disregarded by former colonial powers.

The values of equality and equal rights resonate with resistance to any hegemony, including on a regional level. The structure and decision-making processes of African integration projects (such as SADC, ECOWAS, EAC, and others) are designed to prevent domination by any single country. This is achieved through rotating chairmanship, collective goal-setting, and institutional checks on major players, such as the role of the West African Economic and Monetary Union in relation to Nigeria within ECOWAS (Vanheukelom, 2017), or oversight by the African Union (PSC Report, 2019).

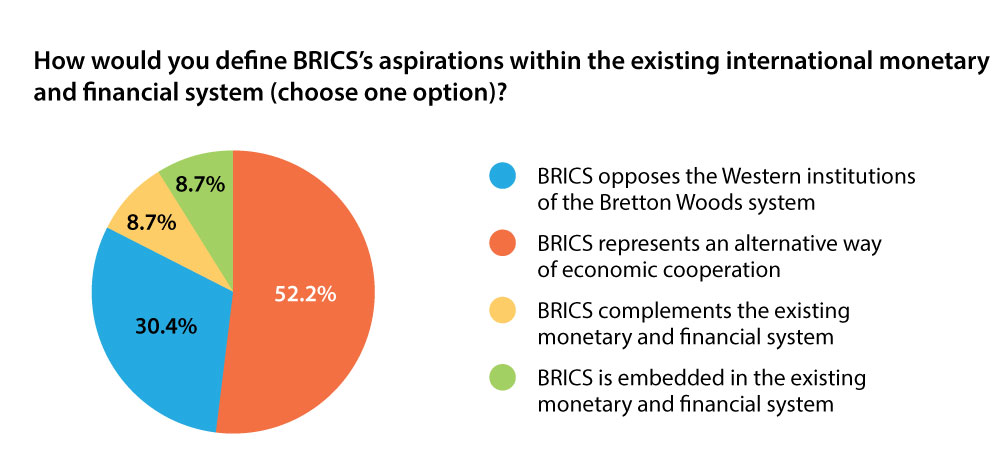

Source: African think tank experts’ poll, MGIMO University grant project KMU-15/01, 2025.

African countries have great expectations of BRICS. Its underlying principles of multipolarity, solidarity, and consensus resonate with Africa’s cultural, religious, and economic diversity. African countries are invested in ensuring that BRICS operational mechanisms are based on a balance of interests, enabling all members, regardless of economic or political weight, to fully participate in shaping the agenda. This idea aligns with the humanistic philosophy of Ubuntu and its emphasis on universal interdependence, which underpins the foreign policies of South Africa and some other countries (Shubin, 2024).

Finally, concerning the sensitive question of whether BRICS is an anti-Western alliance, the designation non-Western (rather than anti-Western), proposed by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, seems particularly fitting for Africa and will likely remain so in the foreseeable future. This delicate approach gives African countries the freedom to choose their international partners.

Social Benefits: A Collective Herald on the International Stage

African countries’ participation in BRICS allows them to garner significantly more clout in international affairs, promote important issues, and support like-minded partners. For instance, the declaration of the 2025 BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro (Declaration, 2025) proclaims BRICS consensus on a wide range of international issues, especially regarding the Middle East: both members and partners unanimously called for an end to Israeli attacks on Gaza, adherence to international humanitarian law, and Palestinian self-determination.

Furthermore, the declaration highlighted a special focus on African conflicts and an adherence to the principle of ‘African solutions to African problems.’ This can be viewed as an achievement of BRICS members advocating for a stronger role of the African Union and greater African agency in resolving crises on the continent, including in Sudan, the Horn of Africa, and the Great Lakes region.

Africa’s vision also aligns with transforming global financial and economic governance, including calls for increasing the quotas of Global South countries in the IMF, as well as moving away from outright protectionism in world trade. Such trends have been characterized as a return to BRICS’s original mission to expand developing countries’ participation in the global economy (Darnal et al, 2025). As with most other international issues, African countries tend to advocate for reforming rather than dismantling institutions. This applies to the WTO, which “remains the only multilateral institution with the necessary mandate, expertise, universal reach, and potential for leadership in multidimensional international trade discussions” (Declaration, 2025, p. 5).

Supporting the Kimberley Process (KP) is also important for Africa. The KP is an international certification program, established in 2000 to prevent global trade in conflict diamonds (‘blood diamonds’). In contrast to recent Western attempts to undermine or rewrite the KP in their own interests, preserving it in its original form will help African countries retain control over their natural resources (Moiseev, 2023).

Finally, working within BRICS enables African countries to align themselves with India, China, and Russia, which offer alternatives to Western-centric narratives and development models. African nations are generally inclined to emulate successful examples and rely on proven strategies.

For example, Uganda Vision 2040 cites Chinese, Indian, and Brazilian development from scratch of computing, biotechnology, and aviation industries, and the countries’ growth of human capital (Uganda Vision 2040, 2013). Nigeria’s national strategy through 2050 references China’s infrastructure development and industrialization model (Nigeria Agenda 2050, 2023, pp. 38, 39, 44). Learning from others’ experience, Africa promotes deeper alignment with BRICS.

Functional Benefits: Bilateral Partners and Multilateral Institutions

In terms of pragmatic value, African countries primarily view BRICS as a platform to stimulate economic growth and expand multilateral cooperation. Within BRICS, Africa is interested in practical, results-oriented efforts aimed at implementing infrastructure projects, developing human capital, and facilitating technological exchange. Access to advanced agricultural and energy technologies could, in the long run, help African nations strengthen domestic production and reduce dependence on imports (Abramova, 2024).

Intra-BRICS cooperation in these areas is expected to follow two parallel paths: bilateral channels with members whose trade volumes exceed $1 trillion, and specialized structures with the rest (Lezhneva, 2025). BRICS’s ‘drivers of development’ are perceived differently across Africa, but each holds specific value: Russia as one of the principal ideologists and defenders of multipolarity; Brazil due to shared identity and historical-cultural ties; and India and China as major investors.

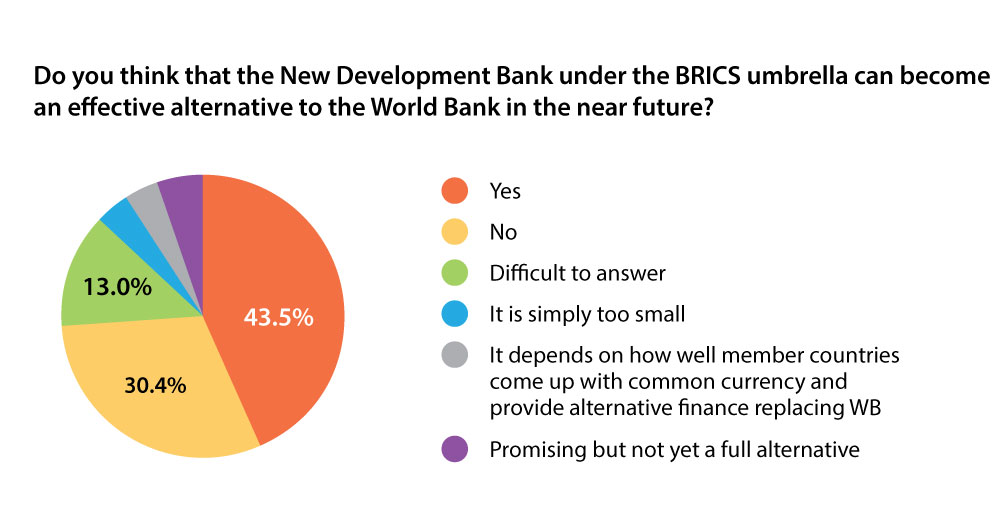

African countries place high hopes in the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) as a way to diversify financing, especially of green technology. However, unresolved issues remain, including the participation of new members such as Ethiopia, their shares in the bank, and the expansion of NDB projects to other African nations. As of now, NDB membership in Africa is limited to South Africa, Egypt, and Algeria. Moreover, the bank is currently unable to facilitate transactions between Russia, a BRICS founding member, and African countries.

Source: African think tank experts’ poll, MGIMO University grant project KMU-15/01, 2025.

New mechanisms within BRICS Pay are intended to expand flexibility. However, despite African countries’ official readiness for transactions in national currencies, they soberly recognize that this is still impossible under the current financial architecture.

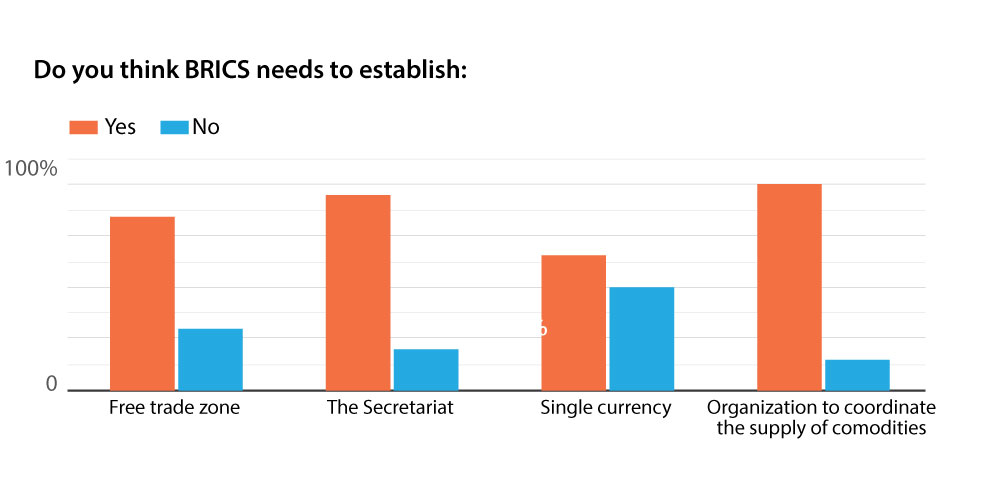

However, surveys of the African academic community show nearly unanimous support for the establishment under BRICS of an organization of natural-resource-exporting countries. Thus, many African elites view BRICS as a pillar of a new economic order that redistributes income towards the Global South and fully integrates Africa into global supply chains.

Source: African think tank experts’ poll, MGIMO University grant project KMU-15/01, 2025.

Is the African Bloc within BRICS United?

Since joining BRICS in 2010, South Africa has served as a bridge between the grouping and the rest of Africa (Zelenova, Andreyeva et al., 2024, pp. 113-114) and used the format to advance African interests (Panin, 2024). For example, the first BRICS summit held in Africa—Johannesburg Summit 2013—became an important catalyst for enhancing cooperation between external actors and African countries in infrastructure, industry, and social development. Today, African influence within BRICS is increasingly evident, as the incorporation of South Africa’s national priorities and broader African initiatives—gender equality, sustainable development, the climate transition, Pan-African integration, and African Union initiatives—were integrated into the 2023 Johannesburg Declaration.

However, South Africa’s role as Africa’s leading voice in BRICS has been diminishing. At the April 2025 foreign ministers’ meeting in Rio de Janeiro, a joint communiqué could not be reached (for the first time ever) due to Egyptian and Ethiopian objections to the draft’s reference to a permanent seat for Africa on the UN Security Council. The wording, proposed by Brazil, implied awarding the seat to South Africa (Fabricius, 2025).

In addition, the expansion of BRICS into Africa is inevitably changing the group’s identity and trajectory of development. For example, while major economies like South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, and Nigeria already serve as regional hubs for finance, trade, agriculture, and industry to varying degrees, Uganda’s GDP is less than one-seventh of Nigeria’s. Uganda’s status as partner (rather than full member) reflects BRICS’s push for a multi-tiered cooperation model. But such heterogeneity may complicate responsibility and burden-sharing, and the coordination of goals and actions.

Western hostility also poses a potential risk to Africa in BRICS. For instance, in July 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump described BRICS as an “anti-American” association threatening U.S. interests and seeking to undermine the U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency. Trump announced a 10-percent tariff (unimplemented as of the time of this publication) on countries supporting BRICS policies. In other words, BRICS integration is being perceived as a challenge to the existing world order. This will force Africa’s export-dependent economies to consider how deeply they can afford to integrate with BRICS.

Finally, political developments within BRICS members/partners can affect the bloc’s plans. For instance, Argentina’s election of Javier Milei in 2023 led to the country’s reversal of accession to BRICS and completely distancing itself from the group.

Some Conclusions and Recommendations

BRICS’s partnership with Africa, and development of an ‘African dimension’ reflect Africa’s movement to the center of international relations and make BRICS attractive to African countries.

The strategic positioning of the BRICS brand in Africa should not be achieved through imposition, but through co-ownership and co-engagement. For African countries, BRICS membership/partnership means symbolic recognition of Africa’s potential and concrete access to new development opportunities.

As it enters the new African space, BRICS must be aware of its responsibility to meet expectations with real initiatives and support. Otherwise, disappointment and threats to the group’s reputation are inevitable. Symbolic steps and ideas must be translated into specific projects in the region. Only then will the group be perceived not as a hollow slogan or a source of elite enrichment, but as an important part of genuine national development strategies.

BRICS is slowly but surely approaching a bifurcation point, where further expansion will reduce effectiveness. In such a scenario, the group faces a choice:

- deepen political coordination and institutional integration, possibly through the introduction of a double majority in decision-making;

- create issue-oriented coalitions/committees with varying degrees of institutionalization. Each country would determine its own specialization within BRICS and oversee it in accordance with national priorities, be they coffee exports or green energy. In this regard, the history of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, with its industrial cooperation between members, may be of interest.

In any case, any of the proposed scenarios should be discussed with the African partners, given Africa’s share in BRICS and the strategic importance to Russia.

This article is an edited and expanded version of the paper written for the Valdai Discussion Club: https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/brics-as-a-brand-and-its-african-dimension/

The authors express their sincere gratitude for the information and results of the survey conducted under grant project KMU-15/01, kindly provided by the project head, Chief Researcher of the Institute of Africa and MGIMO University, Professor Denis Degterev. Full results of the project are due to be released in November 2025.

Abramova, I.O., 2024. Стратегия сотрудничества России со странами Африканского континента: что изменилось после второго саммита Россия–Африка? [Russia’s Strategy of Cooperation with the Countries of the African Continent: What Has Changed after the 2nd Russia–Africa Summit?]. Vestnik Rossiiskoi akademii nauk, 94(6), pp. 500-515. DOI: 10.31857/S0869587324060015

Barabanov, O., 2025. Evolution of the BRICS Platform of Shared Values. Valdai Discussion Club, 8 April. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/a/reports/evolution-of-the-brics-platform-of-shared-values/ [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Darnal, A., Monyae, D., Garcia, A.S., Adhinegara, B.Y., and Stibor, G., 2025. 2025 BRICS Summit: Takeaways and Projections. Stimson, 4 August. Available at: https://www.stimson.org/2025/2025-brics-summit-takeaways-and-projections/ [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Declaration, 2025. The Rio de Janeiro BRICS Declaration. BRICS, 6 July. Available at: https://brics.br/en/documents/presidency-documents [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Fabricius, P., 2025. New Africa BRICS Members Decry Preferential Treatment for South Africa. ISS Today, 14 May. Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/new-africa-brics-members-decry-preferential-treatment-for-south-africa [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Lezhneva, L., 2025. Контрольная покупка: внутренняя торговля стран БРИКС достигла $1 трлн [Test Purchase: Intra-BRICS Trade Reaches $1 Trillion]. Izvestiya, 28 June. Available at: https://iz.ru/1911524/lubov-lezneva/kontrolnaa-pokupka-vnutrennaa-torgovla-stran-briks-dostigla-1-trln [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Moiseev, A., 2023. Comments by Deputy RF Finance Minister Alexey Moiseev on the Results of the 2023 Kimberley Process Plenary Meeting and the G7 and the EU Sanctions Initiatives. RF Ministry of Finance, 23 November. Available at: https://minfin.gov.ru/ru/press-center/?id_4=38750-kommentarii_zamestitelya_ministra_finansov_alekseya_moiseeva_po_itogam_plenarnoi_sessii_kimberliiskogo_protsessa_2023_i_sanktsionnym_initsiativam_g7_i_es [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Nigeria Agenda, 2023. Nigeria Agenda 2050. Available at: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig217433.pdf [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Panin, N., 2024. Фактор БРИКС в дипломатии ЮАР [BRICS Factor in SAR’s Diplomacy]. Russian Council, 16 January. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/faktor-briks-v-diplomatii-yuar/ [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Papa, M., 2024. The Magnetic Pull of BRICS. APRI, 3 December. Available at: https://afripoli.org/the-magnetic-pull-of-brics [Accessed 3 September 2025].

PSC Report, 2019. Defining AU–REC Relations Is Still a Work in Progress. PSC Insights, 1 August. Available at: https://issafrica.org/pscreport/psc-insights/defining-aurec-relations-is-still-a-work-in-progress [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Shubin, V.G., 2024. The External Dimension of the Ubuntu Concept. Journal of the Institute for African Studies, 4, pp. 49-60. Available at: https://africajournal.ru/en/2024/12/28/the-external-dimension-of-the-ubuntu-concept/ [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Tschauko, S., 2025. Branding in International Organizations. Available at: https://stefantschauko.com/research/ [Accessed 03/09/2025].

Uganda Vision 2040, 2013. Uganda Vision 2040. Available at: https://consultations.worldbank.org/content/dam/sites/consultations/doc/migration/vision20204011.pdf [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Vanheukelom, J., 2017. Understanding the Economic Community of West African States. ECDPM. Available at: https://ecdpm.org/application/files/5116/6135/5439/ECOWAS-Background-Paper-PEDRO-Political-Economy-Dynamics-Regional-Organisations-Africa-ECDPM-2017.pdf [Accessed 3 September 2025].

Zelenova, D.A., Andreeva, T.A., Grishenkin, M.S., and Ufimtsev, A.A., 2024. Формирование повестки дня в БРИКС: глобальные проблемы и национальные интересы [Shaping BRICS Agenda: Navigating Global Issues and National Interests]. Kontury globalnykh transformatsiy: politika, ekonomika, pravo, 17(5), pp. 103-122. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31249/kgt/2024.05.06