For citation, please use:

Zuenko, I.Yu., 2025. China’s Activity in Central Asia in Light of Russian Interests. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(2), pp. 146–164. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-2-146-164

China is an immediate neighbor, and the principal economic partner, of post-Soviet Central Asian countries. Their historical ties can be traced back to the Middle Ages. The present border between China and Central Asian countries emerged during the Russian Empire and was finalized in the 1980-2000s. After the collapse of the USSR, Russia retained cultural and economic dominance in Central Asia, but was joined as a player in the region by China, due to the latter’s economic strength and geographical proximity.

As China’s position strengthened and Russia’s waned, their overlapping interests in the former Soviet republics were increasingly seen as a source of future rivalry. And although Russian leaders have repeatedly asserted the convergence rather than collision of the two powers’ interests in Eurasia (Putin, 2023), it remains useful to monitor China’s activity in the region. Moreover, the escalation of the Ukraine crisis in 2022 is likely to discourage former Soviet republics from further rapprochement with Russia, and thus allow China to expand its influence in the region. Currently, that influence is strongest in Central Asia, where it can exemplify Chinese activity in general.

Through the lens of Russian interests, this article analyzes Chinese activity in Central Asia: its context, its general trends, and its dynamics in the areas of trade, investment, education, and military cooperation. The article utilizes a wide range of statistics and public opinion data. Particular attention is paid to the China-Central Asia Format, launched in 2023 and termed here the Xi’an Process, which provides material shedding light on China’s position towards the region.

China’s Central Asia Policy: Systemic Conditions

Top officials in Central Asian countries and China often publicly claim that their historical contacts date back to the journey of Han Dynasty diplomat Zhang Qian in the 2nd century BC (see, e.g., Xi, 2023). However, the current system of relations began to take shape only with Russia’s 19th century expansion into Central Asia, at which point the Russo-Chinese border was largely determined, Russian became the language of modernization and interethnic communication, and economic and cultural ties with Russia displaced those with China.

Also of importance, a significant part of the historical Central Asian Turkic world—Kashgaria and Dzungaria, forming modern Xinjiang—fell within the Chinese state, even as its people retained their linguistic, cultural, and religious identity. On the one hand, this allowed the Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Dungans in those territories to act as cross-border conduits between the Russian part of Central Asia and that within the Qing Empire/China. On the other hand, China’s hardline Sinicization policies towards ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang sparked strong anti-Chinese sentiment in post-Soviet Central Asia (Oka, 2007).

In the last days of the Soviet Union, the Central Asian republics were the least interested in its disintegration, understandably worried that the disruption of trade, economic, and personal ties, the inevitable outflow of Russian specialists, and the delimitation of the republics’ confused borders could trigger a crisis, up to and including the region’s radical Islamization or descent into permanent civil war.[1]

China had similar concerns and feared separatist and extremist spillover to Xinjiang. Thus, in the 1990s and 2000s, Beijing was interested less in economic and cultural expansion, and more in maintaining Central Asia’s stability. It expanded trade and economic ties while creating, together with Russia, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, with which it intended to combat the Three Evils: terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism.[2]

As the Central Asian republics gained statehood (quite successfully, except for Tajikistan’s civil war and Kyrgyzstan’s series of revolutions), the threat of the region becoming a “huge Afghanistan” increasingly gave way to economic issues. Chinese interests include Central Asia’s natural resources (hydrocarbons, uranium, farmland) and its position astride transcontinental trade routes which are not vulnerable to U.S. naval power and which China can safely use to import strategic raw materials and export its industrial goods to international markets.

Both these interests are at the core of the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) initiative, announced in Astana in 2013 and later expanded to the global Belt and Road Initiative. Remarkably, its symbolic and discursive effects have so far been greater than its concrete economic results. The Belt and Road’s references to the Silk Road, and to inner Eurasia’s prosperity, proved so complimentary to the young Central Asian states that they readily supported it and developed their own initiatives that parallel Chinese discourse (for instance, Kazakhstan’s Nurly Zhol infrastructure project, announced in 2014.) They have thus acquired (and retained) inflated expectations of Chinese investment and technology, but these have themselves fueled xenophobic sentiment, supported by pro-Western media and NGOs that became more active in the region precisely in the mid-2010s.

China is seen as a potential replacement for Russia in the “post-colonial” discourse that intensified after the start of the Special Military Operation (SMO) in February 2022 (as evidenced, inter alia, by relevant sociological surveys conducted and published in Kazakhstan (DEMOSCOPE, 2023.)) Advocates emphasize the opportunities offered by China, from the upgrade of transport and logistics capabilities (which Central Asian elites see as key to their prosperity, as during the Silk Road era) to education in Chinese universities (Informburo, 2023).

But China is also seen as an economic and demographic threat. In the latter respect, it is feared as capable of assimilating Central Asia’s relatively small populations, if Chinese settlement and interethnic contacts were to intensify (Laruelle and Peyrouse, 2009, pp. 167-168). This perception is particularly strong in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, which directly border on China, and it led to a series of major anti-Chinese protests in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in 2019-2020 (Kulintsev et al., 2020). Anti-Chinese sentiment is also fueled by the strained situation in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which Central Asians learn about through the above-mentioned cross-border contacts.

This ambivalent perception of China, coupled with the Central Asian countries’ traditional focus on a multivector policy and balancing between external players, prompt a cautious approach—maximum cooperation with China while preventing its excessive strengthening in any sphere. These are the systemic conditions under which China is implementing its policy in Central Asia.

The History and Current Trends of China’s Central Asia Strategy

China’s strategy in Central Asia since the early 1990s has gone through four stages:

- In the 1990s, China established ties with the newly independent post-Soviet states, while exercising caution and seeking to avoid risks stemming from the region’s possible destabilization. This period was marked by the creation of the Shanghai Five in 1996 and by the final settlement of China’s border with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. At this stage, the resolution of priority tasks was impossible without close coordination with Russia, which was seen as a key guarantor of stability, security, and economic development in the region.

- In 2001-2013, cooperation between China and Central Asian countries expanded due to sustainable economic ties (a major event was the construction of the Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline, with the first section commissioned in 2009) and the creation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001. At this stage, Russia’s importance as the “only adult in the room” decreased, but it still played a crucial role in providing a safe environment in which China could increase its economic presence.

- In 2013-2023, the Silk Road Economic Belt initiative was launched and Chinese investments proliferated (Soboleva and Krivokhizh, 2021). Flagship projects included the Kazakhstani section (completed in 2017) of the Western China-Western Europe transport corridor, and the beginning of work on the fourth section of the Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline through Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Inflated expectations of Chinese investments meant that less importance was ascribed to Russia. Yet China still saw coordination with Russia as crucial for maintaining stability and expanding its trade and other plans in the region, hence the May 2015 joint Russo-Chinese statement on integrating the Eurasian Economic Union and Silk Road Economic Belt.

- In May 2023, the current stage in China’s strategy towards the region began with the China-Central Asia Summit and resulting Xi’an Declaration. Xi Jinping’s speech at the Summit should be considered as declaring China’s strategy in the region (Government of China, 2023). The China-Central Asia permanent secretariat’s activation, in Xi’an in March 2024, marks the launch of a new integration organization, one differentiated from predecessors by China’s pursuit of political (not only economic) objectives and by the absence of Russia.

Thus, Russia’s regional influence, across these four stages, has been steadily decreasing (Borisov and Karmanova, 2024).

Prospects for the China-Central Asia Format

While establishing integration platforms with various actors, Central Asian countries neither step aside from their strategy of multivector cooperation with other countries nor allow any one actor (including China) to critically consolidate its influence in the region.[3]

The development of the China-Central Asia Format began amid the SMO, which largely molded the region’s attitude towards Russia. Public opinion in Central Asian countries (especially Kazakhstan) sharply swung against Russia, associated with expectations of Russia’s imminent economic collapse and the destabilization of trade, economic, and personal ties with it (Demoscope, 2022a, 2022b, 2023).[4] This helped elites and the general public overcome alarmism about China and secure media support for the Xi’an Process.

Likewise, the abolition of visas between China and Kazakhstan in 2023, and negotiations on the relaxation of the visa regime between China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan in 2023-2024, were perceived by Central Asian elites as a gesture of trust and recognition of status.[5]

Notably, Central Asia is not the only region where China has established a multilateral dialogue with the local countries. There are similar formats in Africa (the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation), in Latin America (the China-CELAC Forum), in the Middle East (the China–Arab States Cooperation Forum), in Central and Eastern Europe (the 14+1 Format), and elsewhere. These host discussions of regional cooperation and specific bilateral projects.

The Xi’an Declaration of 2023, in addition to creating a permanent secretariat, calls for the establishment of a China-Central Asia business council (to coordinate the work of businesses and chambers of commerce) and for meetings of foreign and economic ministers. Future summits are to be accompanied by the China-Central Asia Industrial and Investment Cooperation Forum. However, the benefits of this business communication infrastructure should not be overestimated. Other players (including Russia) are creating similar infrastructure, and in practice such formats often become vacuous unless backed up by bilateral cooperation agenda.

Thus, China’s advance in Central Asia should be assessed not on the basis of rhetoric about integration or of a “struggle between the great powers” (as in Bossuyt and Kaczmarski, 2021) but based on concrete results—especially in the economy, education, and military cooperation, where Russia has historically held preeminence.

China-Central Asia Trade

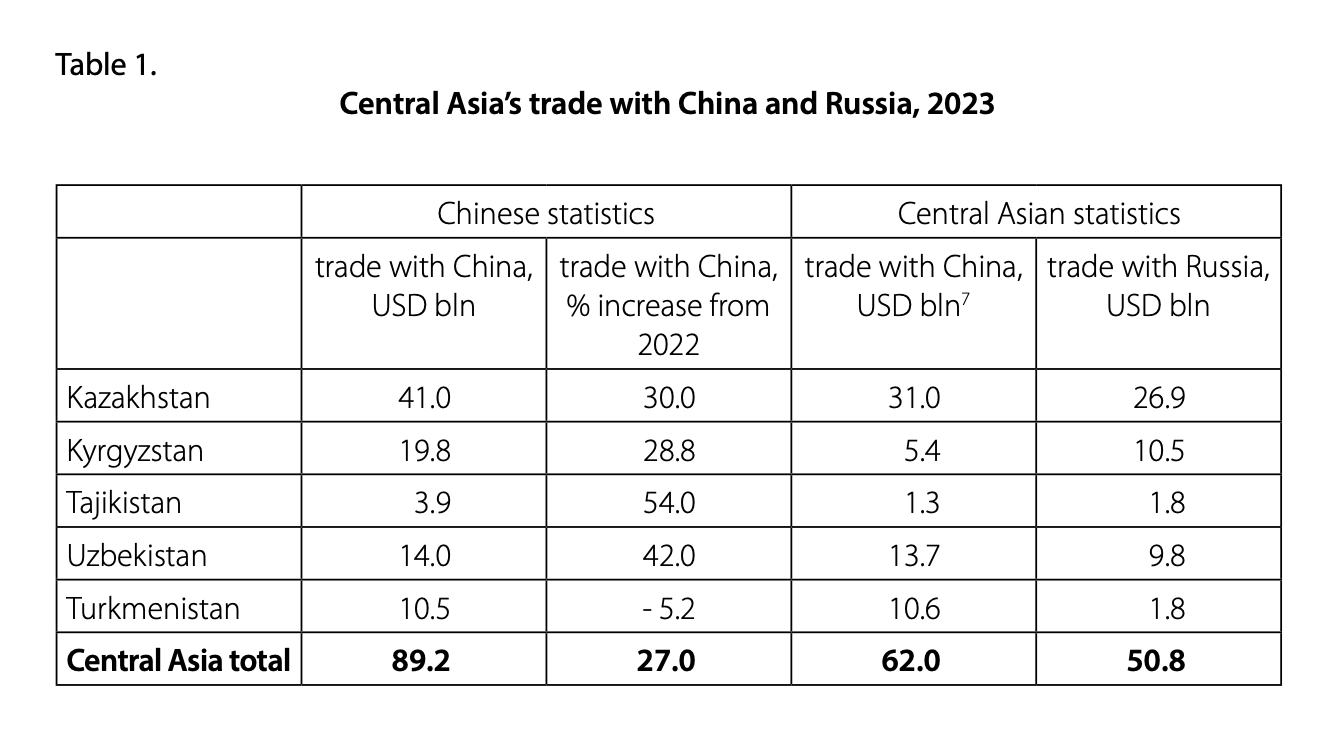

China-Central Asia trade increased considerably in 2022-2024, partly due to “parallel import” from China to Russia through third countries (primarily in the EAEU).[6]

Since 2022-2023, China has been clearly ahead of Russia as Central Asia’s main trading partner, mainly on account of its growing exports. The only exception is Turkmenistan, whose main export commodity is natural gas supplied under long-term contracts, which explains minimal fluctuations in trade statistics. This trend seems irreversible and parallels that of other Eurasian countries. However, the region’s trade with Russia also remains substantial.

Chinese Investment in Central Asia

China is widely perceived as the main investor in Central Asia. While measuring foreign investment is difficult, China’s investments in Central Asia are clearly significant, exceeding Russia’s and being quite comparable to China’s investments in other regions.

Per the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, cumulative direct Chinese investment in Central Asia had reached $63.9 billion by the Xi’an Summit in 2023 (including $15 billion in 2022 alone), financing various energy, transport, and manufacturing projects (National Development and Reform Commission, 2023), whereas Russia’s cumulative and 2022 investments were $23.9 and $3.6 billion, respectively (Eurasian Development Bank, 2023). At the summit, China announced 26 billion yuan (about $3.7 billion) to support Central Asia’s sustainable development, although the destination and use of these funds remains unclear.

In line with Beijing’s priorities for the region, more than half of declared Chinese investments are in energy (production and transportation).[8] As for transport infrastructure—where Central Asia’s expectations have been elevated since the announcement of the SREB ten years ago—the situation is not so positive. Kazakhstan has seen the greatest logistical improvements, building several ‘straightened’ railway lines, ports on the Caspian Sea, and the ‘dry port’ of Khorgos, but without Chinese investment.

Yet such conditions are frowned upon in post-Soviet states that are generally confident in their irreplaceability and importance, and prefer to await better offers (see also Zuenko, 2024).

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway project is emblematic of this, as its implementation was postponed for many years by Kyrgyzstan’s demands for compensation from China and Uzbekistan as the project’s main beneficiaries. Some progress was reached only in 2023-2024 after the 2022 Samarkand SCO Summit, but a feasibility study is still unfinished. Similarly, the Xi’an Declaration does not contain any new ambitious transport or logistics projects, merely stating the importance of building the Ayaguz-Tacheng railway line (discussed since 2017) between Kazakhstan and China, and of the smooth functioning of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan, China-Tajikistan-Uzbekistan, and Western China-Western Europe highways (People’s Daily, 2023).

Education

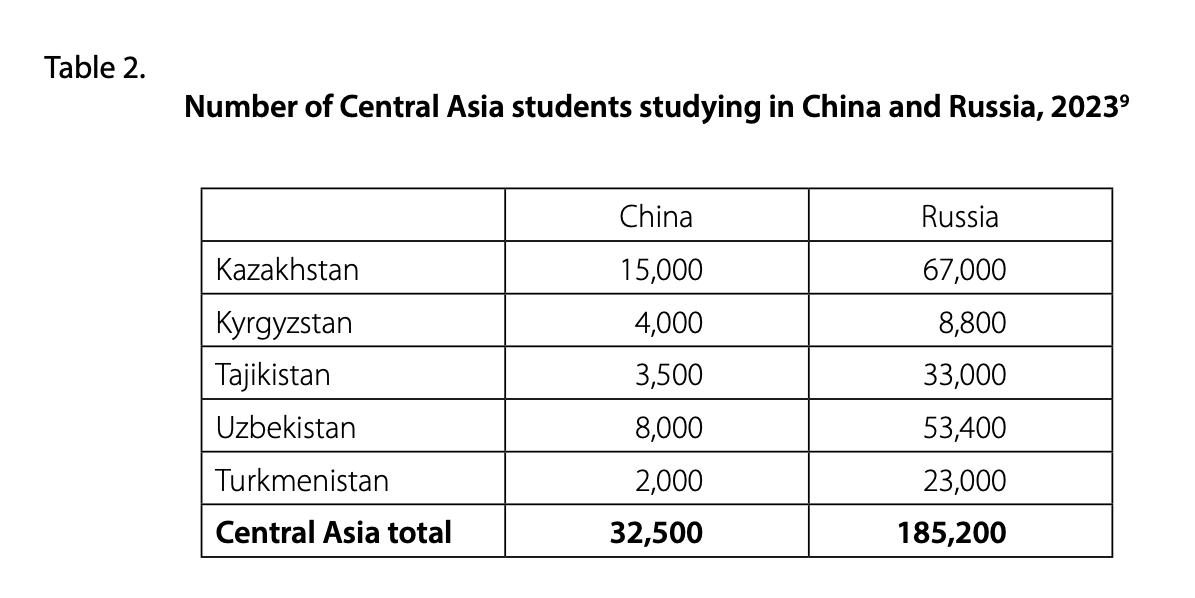

China’s education strategy is being implemented as part of the Cultural Silk Road concept, mentioned in the Xi’an Declaration. Student exchange programs resumed after the COVID-19 pandemic ended and travel restrictions were lifted. Work in this area intensified significantly in 2023-2024.

The example of Kazakhstan is indicative. It ranks among the top ten sources of foreign students studying in China, which is touted in the media as proving the popularity of Chinese education among young Kazakhstanis. However, foreign education is more popular among Kazakhstanis than in any other population in the world: 0.48% of the total population was studying abroad in 2023, and about 50% of all school graduates in 2023 enrolled in higher education programs abroad (Standard.kz, 2024). And Russia remains the most popular destination of all: 67,000 out of 90,000 Kazakhstanis studying abroad chose Russia (see: Embassy of Kazakhstan 2023).

There are also Chinese-funded educational institutions in the region, including 13 Confucius Institutes[10] and two Lu Ban Workshops[11] (compared to 23 and zero, respectively, in Russia).

In 2023, Chinese Vice Minister of Education Sun Yao visited Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan in order to address technical issues concerning the opening of such branches. In October of the same year, China’s Northwestern Polytechnical University (Xi’an) opened a branch in Almaty. Kyrgyzstan’s Balasagyn National University and China’s Henan University (Zhengzhou) created the Silk Road Institute. Uzbekistan’s President has also expressed interest in opening branches of leading Chinese universities (Uz-24, 2023). Yet, in comparison, 24 branches of Russian universities already work in Central Asia, plus separate Kyrgyz-Russian and Tajik-Russian universities in Bishkek and Dushanbe.[12] Established on China’s initiative, the University Alliance of the Silk Road, in operation since 2015, brings together seven universities from Kazakhstan, seven from Kyrgyzstan, two from Tajikistan, two from Turkmenistan, and one international university based in Uzbekistan (compare to 27 from Russia). So, despite China’s increased efforts to expand its university branches in Central Asia, it still falls far behind Russia in this area.

Military Cooperation

Currently, China has a military presence only in Tajikistan, which is important for Beijing as a bridgehead to Afghanistan and northern Pakistan. In 2016, China initiated a quadripartite mechanism for military cooperation and coordination with Tajikistan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, but it is now in limbo after the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan. According to some Western sources (Shih, 2019; Schulz, 2021), the People’s Armed Police are deployed in the Murghab district of the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region of Tajikistan, though Dushanbe denies this. In addition, since 2021, a Chinese construction company has been building a base in the Ishkoshim district to be used by the Tajik Ministry of Internal Affairs.[13]

Since the mid-2010s, Central Asian countries have increased purchases of Chinese arms: UAVs (Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan), armored vehicles (Tajikistan), anti-aircraft missile systems and artillery shells (Uzbekistan), and transport aircraft (Kazakhstan). Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan stand out in military-technical cooperation with China, with Chinese weapons making up more than 20% of their total arms purchases.

While Russian weapons predominate over Chinese in the CSTO—85 to 1 in Kazakhstan, 53 to 1 in Kyrgyzstan, and 27 to 1 in Tajikistan—this is not so in Uzbekistan (6 to 4) or Turkmenistan (54 to 46) (Zholdas, 2021). Since 2022, Russian arms exports have decreased in Central Asia and generally, their overall quantity falling by 52% in 2023 alone (TASS, 2024)). China’s share in Central Asia has thus presumably increased, but the region shrank to a mere 0.1% of global arms purchases in 2022 (SIPRI, 2023).

Experts from anti-Russian Western think tanks claim a growing distrust of Russia as “security provider,” given the “failure of Russian arms” during the SMO in 2022 (Sharifli, 2023). However, negotiations and decision-making on arms purchases are lengthy affairs, and thus the situation on the front line could not be reflected so quickly. Moreover, the success of Russian troops in 2023-2024 should, according to this logic, have just as rapidly led to an increase in purchases from Russia.

Rather, the general trend in Central Asia is a result of the republics’ pursuit of diversified relationships, which has led even to increased Uzbek purchases of U.S. weaponry (U.S. Embassy in Uzbekistan, 2022).

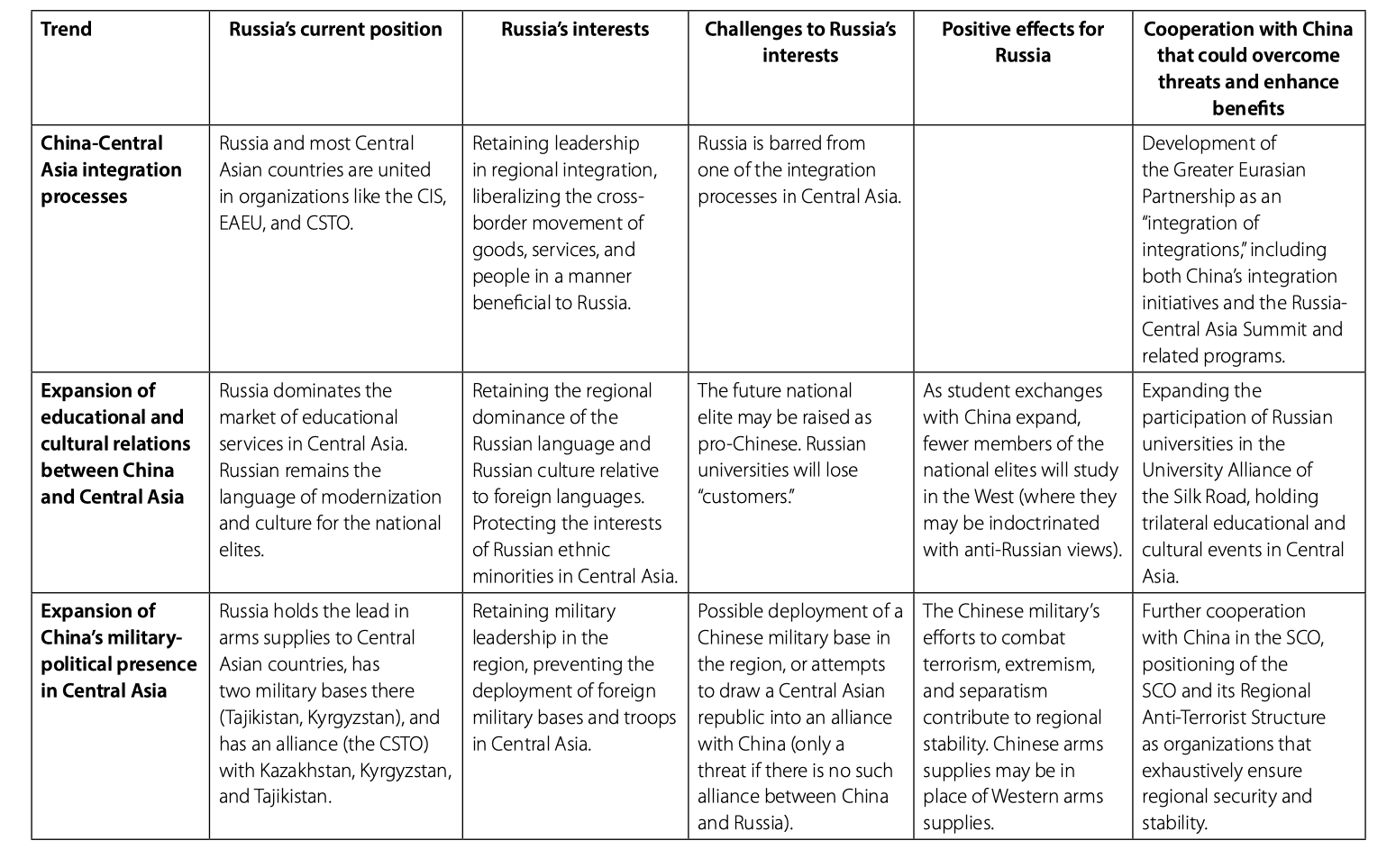

Challenges and Benefits for Russia

Current trends in China’s presence, and their impact on Russian-Chinese cooperation in the region, are summarized in Table 3.

For Russia, currently locked in confrontation with the West, China’s presence in Central Asia promises not only challenges, but also benefits, such as enhanced security and economic interconnectedness, providing Russia with necessary goods and filling vacuums that might otherwise be occupied by unfriendly countries. Also, China’s influence, unlike the West’s, neither ousts governments that favor constructive relations with Russia, nor suppresses ethnic Russians, the Russian language, traditional moral values, or memory of the victory in World War II.

Aside from the economy, Russia’s military and educational dominance in the region is clear and probably unchallengeable by China, whose influence is limited by a deep-seated Sinophobia with historical-cultural roots that only intensifies as China’s presence expands. Chinese is unlikely to supplant Russian as the language of interethnic or inter-elite communication within several decades or even half a century. Although criticized, Russian-initiated integration projects (the CSTO and the EAEU) continue to operate quite successfully, and China is unable to offer an effective alternative to them. This is particularly clear in the CSTO’s rescue of Tokayev in January 2022.

The SMO has somewhat shifted the balance of influence between Russia and China in the region. Public reaction was largely anti-Russian (especially in Kazakhstan, gripped by the fear of losing its northern territories). The national elites in Central Asia began seeking to diversify their international cooperation. Businesses feared the unprecedented Western sanctions imposed on Russia. This created a window of opportunity for China, which it has used to advance the Xi’an Process. But is expanding this window, and/or squeezing Russia out of the region, China’s strategic goal?

At the Xi’an Summit in May 2023, President Xi stated that China needs a Central Asia that is: “1. stable, 2. prosperous (thereby contributing to the post-pandemic global economic recovery), 3. harmonious (without interethnic conflict), and 4. interconnected (connecting East to West)”. Priority is given to stability, and none of the goals can be achieved without Russia.

Therefore, Russia should itself seek not to expel China from Central Asia, but to develop mutually-beneficial cooperation with it there, based on the Greater Eurasian Partnership and existing organizations like the SCO.

[1] On the attitude of the new states’ elites, see Ibraimov, 2015. (The author is Kyrgyz Republic’s former deputy prime minister and secretary of state.)

[2] The Shanghai Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism was signed by the SCO heads of state, simultaneously with the Declaration on the Establishment of the SCO, on 14 June 2001 (see President of Russia, 2001). In Chinese documents, the expression “Three Evils” (三股势力) has been used since 2004.

[3] One should also mention the Central Asia–Germany summits held in 2023 and 2024, and the Central Asia–Japan summits of 2024.

[4] However, public opinion data in Central Asia may be unreliable or affected by local analysts’ self-censorship.

[5] The opposite took place in 2016-2019, when China unilaterally tightened visa requirements for Kazakhstanis, and essentially stopped issuing visas to Kyrgyzstanis after its Bishkek embassy was bombed.

[6] As evidenced by the abnormal growth of Chinese imports to Kazakhstan (52.8% at the end of 2023, worth $24.7 billion).

[7] Customs discrepancies between China and post-Soviet countries are well-known, caused by methodological peculiarities (e.g., the exporter does not account for freight and insurance costs) and by re-export.

[8] In addition to the above-mentioned four gas pipeline branches connecting Turkmenistan and China, there are 20 more projects worth $18.8 billion in Kazakhstan, 12 projects worth $205 million in Uzbekistan, and 16 projects worth $15 billion in other countries (Aminjonov et al., 2019).

[9] Compiled using data from Trotsky et al. (2024), Embassy of Kazakhstan (2023), CABAR (2023), Anhor.uz (2024), Aslonova (2024). Note: while Chinese statistics include only students studying at universities, Russian statistics include young people who come to Russia to study in other educational institutions, including vocational and technical schools as well.

[10] Five in Kazakhstan, four in Kyrgyzstan, two in Uzbekistan, and two in Tajikistan, plus 24 Confucian classes.

[11] In November 2022 and December 2023, workshops opened at the Tajik Technical University in Dushanbe and the Serikbayev East Kazakhstan Technical University in Ust-Kamenogorsk.

[12] Calculated by the author based on the analysis of open data.

[13] In addition to numerous mention of these facilities by Western media, they were also described in an article written for the Russian International Affairs Council by Tajik researcher A. Dodikhudo, who relied, among other things, on the information gathered during her professional trip to the village of Shaimak, Murghab district (see Dodikhudo, 2023).

_________________________

Aminjonov, F., Overland, I., and Vakulchuk, R., 2019. BRI in Central Asia: Energy Connectivity Projects. Central Asia Regional Data Review, 22, pp. 1-14.

Anhor.uz, 2024. Что происходит с молодежью Центральной Азии, следующей по “образовательному пути” Китая [What Is Happening to the Young People in Central Asia Following China’s “Educational Path”]. Anhor.uz, 2 January. Available at: https://anhor.uz/vzglyad-iznutri/central-asian-youth/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Aslonova, N., 2024. Минобрнауки назвало число обучающихся за границей таджикских студентов [The Ministry of Education and Science Has Named the Number of Tajik Students Studying Abroad]. Asia-Plus, 27 August. Available at: https://asiaplustj.info/ru/news/tajikistan/society/20240827/minobrnauki-nazvalo-chislo-obuchayutshihsya-za-granitsei-tadzhikskih-studentov [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Borisov, D.A. and Karmanova, L.A., 2024. Периодизация внешней политики КНР в отношении Центрально-Азиатского региона (1990–2024 гг.) [Periodization of China’s Foreign Policy towards the Central Asian Region (1990–2024]. Bulletin of the Institute of Oriental Studies, 2(62), pp. 97-108.

Bossuyt, F. and Kaczmarski, M., 2021. Russia and China between Cooperation and Competition at the Regional and Global Levels. Introduction. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 62(5-6), pp. 539-556.

CABAR, 2023. Образовательные проекты Китая как инструмент мягкой силы в Казахстане [China’s Educational Projects as a Soft Power Tool in Kazakhstan]. CABAR, 22 June. Available at: https://cabar.asia/ru/obrazovatelnye-proekty-kitaya-kak-instrument-myagkoj-sily-v-kazahstane [Accessed 10 January 2025].

DEMOSCOPE, 2022a. Вторжение российских войск в Украину [Invasion of Russian Troops in Ukraine]. DEMOSCOPE, 7 April. Available at: https://demos.kz/scenarij-oprosa/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

DEMOSCOPE, 2022b. Отношение казахстанцев к войне в Украине [The Attitude of Kazakhstanis to the War in Ukraine]. DEMOSCOPE, 30 November. Available at: https://demos.kz/otnoshenie-kazahstancev-k-vojne-v-ukraine-2/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

DEMOSCOPE, 2023. Пресс-релиз и инфографика на казахском и русском языках [Press Release and Infographic in Kazakh and Russian]. DEMOSCOPE, 17 May. Available at: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1RDIrM8GxTxh4yaCBbHED-Qc1CZn9wSMd?usp=sharing [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Dodikhudo, A., 2023. Свято место пусто не бывает, или Как Пекин становится ближе для Таджикистана [A Holy Place Is Never Empty, or How Beijing Is Becoming Closer to Tajikistan]. RIAC, 13 September. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/columns/sandbox/svyato-mesto-pusto-ne-byvaet-ili-kak-pekin-stanovitsya-blizhe-dlya-tadzhikistana/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Embassy of Kazakhstan, 2023. Информация по ВУЗам [Information According to University Data]. Embassy of Kazakhstan, n.d. Available at: https://kazembassy.ru/rus/studenty/vuzy [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Eurasian Development Bank, 2023. Мониторинг взаимных инвестиций ЕАБР – 2023 [Monitoring of Mutual Investments of the EDB – 2023]. Eurasian Development Bank, 19 December. Available at: https://eabr.org/analytics/special-reports/monitoring-vzaimnykh-investitsiy-eabr-2023/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

General Administration of Customs of China, 2023. 年统计月报 [Tables of Import-Export Volume by Country (Region) in 2023]. General Administration of Customs of China, n.d. Available at: gdfs.customs.gov.cn/customs/302249/zfxxgk/2799825/302274/302277/4899681/index.html [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Ibraimov, O., 2015. История кыргызского государства [The History of the Kyrgyz State]. Bishkek: Uyluu toolor.

Informburo, 2023. Эксперт: “Один пояс, один путь” стал для Казахстана прорывным проектом [Expert: One Belt, One Road Has Become a Breakthrough Project for Kazakhstan]. Informburo, 20 October. Available at: https://informburo.kz/stati/ekspert-odin-poyas-odin-put-stal-dlya-kazaxstana-proryvnym-proektom [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Kulintsev, Yu.V., Mukambaev, A.A., Rakhimov, K.K. and Zuenko, I.Yu., 2020. Sinophobia in the Post-Soviet Space. Russia in Global Affairs, 18(3), pp. 128-151. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2020-18-3-128-151

Laruelle, M. and Peyrouse, S., 2009. China As a Neighbor: Central Asian Perspectives and Strategies. Washington: John Hopkins University.

National Development and Reform Commission, 2023. 中国-中亚峰会为地区繁荣发展注入新动力 [China-Central Asia Summit Gives New Impetus to Regional Prosperity and Development]. National Development and Reform Commission, 2 June. Available at: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/wsdwhfz/202306/t20230602_1357181.html [Accessed 10 January 2025].

National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic, 2023. Внешняя торговля [External Trade]. National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic, n.d. Available at: https://stat.gov.kg/ru/statistics/vneshneekonomicheskaya-deyatelnost/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Oka, N., 2007. Managing Ethnicity under Authoritarian Rule: Transborder Nationalisms in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Chiba: IDE Press.

People’s Daily, 2023. Полный текст Сианьской декларации саммита “Китай — Центральная Азия” [Full Text of the Xi’an Declaration of the China-Central Asia Summit]. People’s Daily, 19 May. Available at: http://russian.people.com.cn/n3/2023/0519/c31521-20021203.html [Accessed 10 January 2025].

President of Russia, 2001. Шанхайская конвенция о борьбе с терроризмом, сепаратизмом и экстремизмом [The Shanghai Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism]. President of Russia, 14 June. Available at: http://kremlin.ru/supplement/3405 [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Putin, V.V., 2023. Россия и Китай – партнёрство, устремлённое в будущее [Russia and China – A Partnership Looking to the Future]. TASS, 20 March. Available at: https://tass.ru/politika/17312135 [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Qazstat, 2023. Внешнеторговый оборот Республики Казахстан (январь-декабрь 2023 г.) [Foreign Trade Turnover of the Republic of Kazakhstan (January-December 2023)]. Qazstat, 15 February. Available at: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/industries/economy/foreign-market/publications/123068/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Schulz, D., 2021. China Advances Security Apparatus in Tajikistan in the Aftermath of the Taliban Takeover. Caspian Policy Center. Available at: https://www.caspianpolicy.org/research/security-and-politics-program-spp/china-advances-security-apparatus-in-tajikistan-in-the-aftermath-of-the-taliban-takeover-13254 [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Sharifli, Yu., 2023. China’s Dominance in Central Asia: Myth or Reality? Royal United Service Institute, 18 January. Available at: https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/chinas-dominance-central-asia-myth-or-reality [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Shih, G., 2019. In Central Asia’s Forbidding Highlands, a Quiet Newcomer: Chinese Troops. The Washington Post, 18 February. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-central-asias-forbidding-highlands-a-quiet-newcomer-chinese-troops/2019/02/18/78d4a8d0-1e62-11e9-a759-2b8541bbbe20_story.html [Accessed 10 January 2025].

SIPRI, 2023. Trends in World Military Expenditure. SIPRI, 1 April. Available at: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/2304_fs_milex_2022.pdf [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Standard.kz, 2024. Сколько казахстанских студентов учится за рубежом? [How Many Kazakhstani Students Study Abroad?]. Standard.kz, 4 July. Available at: https://standard.kz/ru/post/2024_07_skolko-kazaxstanskix-studentov-ucitsia-za-rubezom-387 [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Soboleva, E. and Krivokhizh, S., 2021. Chinese Initiatives in Central Asia: Claim for Regional Leadership? Eurasian Geography and Economics, 62(5-6), pp. 634-658.

TASS, 2024. В SIPRI сообщили, что закупки вооружений странами Европы в 2019–2023 годах почти удвоились [SIPRI Reports Arms Purchases by European Countries Almost Doubled in 2019–2023.]. TASS, 11 March. Available at: https://tass.ru/ekonomika/20196739 [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Trotsky, Ye., Yun, S., and Pogorelskaya, A., 2024. Интернационализация высшего образования в Центральной Азии и роль России [Internationalization of Higher Education in Central Asia and the Role of Russia]. RIAC, 27 August. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/internatsionalizatsiya-vysshego-obrazovaniya-v-tsentralnoy-azii-i-rol-rossii/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

US Embassy in Uzbekistan, 2022. United States Presents Military Equipment to Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Defense. US Embassy in Uzbekistan, 26 October. Available at: https://uz.usembassy.gov/united-states-presents-military-equipment-to-uzbekistans-ministry-of-defense/ [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Uz-24, 2023. Президент Узбекистана предложил открыть в Ташкенте филиалы китайских вузов – Университета Цинхуа и Пекинского университета [The President of Uzbekistan Has Proposed to Open Branches of Two Chinese Universities in Tashkent – Tsinghua University and Peking University.]. Uz-24, 17 October. Available at: https://uz24.uz/ru/articles/dva-vuza [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Uzstat, 2023. Внешнеторговый оборот Республики Узбекистан (за январь-декабрь 2023 г.) [Foreign Trade Turnover of the Republic of Uzbekistan (January-December 2023)]. Uzstat, 20 January. Available at: https://stat.uz/ru/press-tsentr/novosti-goskomstata/49770-o-zbekiston-respublikasi-tashqi-savdo-aylanmasi-2023-yil-yanvar-dekabr-5 [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Xi Jinping, 2023. 习近平在中国-中亚峰会上的主旨讲话 [Speech by Xi Jinping at China-Central Asia Summit 2023]. Available at: gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202305/content_6874886.htm [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Zholdas, A., 2021. Import of Arms in Central Asia: Trends and Directions for Diversification. Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting, 1 October. URL: https://cabar.asia/en/import-of-arms-in-central-asia-trends-and-directions-for-diversification [Accessed 10 January 2025].

Zuenko, I.Yu. and Zuban, S.V., 2017. Китай и ЕАЭС: динамика трансграничного движения товаров и будущее евразийской интеграции [China and the EAEU: The Dynamics of Cross-Border Movement of Goods and the Future of Eurasian Integration]. Customs Policy of Russia in the Far East, 2, pp. 5-24.

Zuenko, I.Yu., 2024. Проблемы развития международных транспортных коридоров “Восток – Запад” в Каспийском регионе [Problems of the Development of East-West International Transport Corridors in the Caspian Region]. Journal of Frontier Studies, 4, pp. 169-185.