For citation, please use:

Kotliarov, I.D., 2025. Crowdfunding the Army: Implementation and Implications. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(2), pp. 75–86. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-2-75-86

The hostilities that began in the Donbass in 2014 have demonstrated crowdfunding’s importance in providing additional resources to the military (Stewart, 2015). Crowdfunding (and, more broadly, crowdsourcing and fundraising) helped Ukraine overcome the consequences of ineffective post-1991 military policy and the destabilizing 2013-2014 Maidan, providing material and medical support to new highly-motivated units (Boichak and Asmolov, 2021; Khoma, 2023; Redko et al., 2022).

Ukraine’s reliance on crowdfunding grew further after the February 2022 launch of Russia’s Special Military Operation, partly compensating for Ukraine’s smaller military-economic potential and military budget.

Of course, Western aid is a crucial source of funding for Ukraine’s military and security agencies (Yevtodyeva, 2023; Shchipansky et al., 2022; Marsh, 2023), but crowdfunding plays a prominent role, too (Champion and Krasnolutska, 2023; Spansvoll, 2024; Wood, 2022). Although its share in Ukraine’s military spending is far from impressive (according to open sources, it amounts to about 3% (Méheut and Mitiuk 2024)), crowdfunding has proven instrumental in providing drones and building a new branch of the Ukrainian Armed Forces—the Unmanned Systems Forces (Hawser, 2022; Loh, 2024; Roblin, 2023).

Despite its larger budget, the Russian military also benefits from crowdfunding and fundraising (Skorobogaty, 2022). Regular campaigns provide additional resources, make supplies more flexible, and improve the quality of military personnel’s life, as recognized by the Russian leadership (Shakirov, 2024).

Research has examined the crowdfunding of military supplies (Asmolov, 2022; Khoma, 2023; Redko et al., 2022; Grove, 2019), and the place of crowdfunding and crowdsourcing in the digital transformation of warfare (Nilsson and Eckman, 2024; Zarembo et al., 2024; Boichak and Hoskins, 2022). However, other important issues related to military crowdfunding—varieties of military crowdfunding, its impact on army sustainment, counteraction to crowdfunding in support of the enemy, etc.—remain understudied.

The article is based on available foreign and Russian literature that describes the nature of crowdfunding as an innovative tool of financing commercial and non-commercial projects and identifies its main types (Langley, 2016; Paschen, 2017; Schneor, 2020) and various crowdfunding practices described in the media.

In its traditional meaning, crowdfunding means raising resources (most often financial) from a large number of individuals and foundations to facilitate a project’s implementation (Langley, 2016; Paschen, 2017). Crowdfunding is similar to fundraising in that resources are collected by a large number of donators, but it differs from the latter exactly for its specific purpose (Kotliarov, 2024). Since public and business organizations often use croudfunding and fundraising simultaneously, these terms are used herein as synonyms.

Military Crowdfunding by Type of Provided Resource

Military crowdfunding and fundraising campaigns may be initiated by the state, its armed forces, their units, or even individual servicemen, who publicly post information about the purpose of the campaign and details of the bank accounts to which donations may be sent. If the recipient is a state or its military, donations are added to the budget for supplies.

However, units or individuals may use donations to directly purchase equipment or goods that are not officially provided. This resource crowdfunding provides soldiers with direct access to society’s funds.

In tentatively-labeled service crowdfunding, funds are raised by specialized, permanent, usually volunteer organizations that support the military (Asmolov, 2022) with non-combat functions such as medical care (field hospitals, evacuation of the wounded, etc.) or supply (e.g., procurement centers that take requests from military units for clothing, communications equipment, etc., purchase it, and deliver it to the front line). Such volunteer organizations (which can be described as altenative sustainment providers) operating on a permanent basis and financed through donations, free up military units and compensate for failures in the official military logistics system, increasing the quality and sustainability of supply. The use of alternative sustainment structures augments the official resource supply chains: troops can diversify their sources of materiel, overcoming the bureaucratic procedures and rigidness of the official resource supply chains that hamper operation in a swiftly changing combat environment.

Industrial crowdfunding supports the manufacture of products that are not available on the consumer market. For instance, the Russian drone Upyr (Ghoul) was created entirely thanks to donations (Kots, 2024). While service crowdfunding compensates for inflexibility in the official logistics system, industrial crowdfunding compensates for inflexibility in the defense industry. Effective industrial crowdfunding provides the military with fundamentally new weapons. For instance, Ukraine has created a new branch—the Unmanned Systems Forces—based on the crowdfunded Drone Army project.

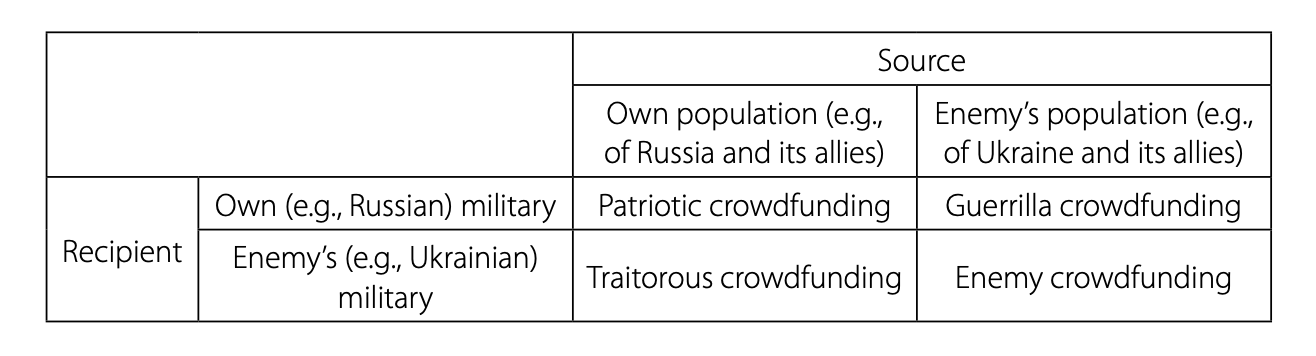

Military Crowdfunding by Source and Recipient

Aside from the type of resource being provided, crowdfunding can also be categorized on the basis of the source and recipient of the funds:

Note that even nominally non-military aid may be used for military purposes (e.g., supplying ambulances and medical equipment to civilian hospitals does not formally support the army, but it does facilitate the care of wounded soldiers in these hospitals as even people who donate ambulances admit).

Patriotic Crowdfunding

The effectiveness of patriotic crowdfunding requires:

- Improved effectiveness by reaching more donors and increasing the amount of funds raised. Relevant tools and strategies for civilian commercial and non-commercial crowdfunding have been extensively described (De Crescenzo et al., 2021; Domínguez-Borrero et al., 2020; Wenzlaff, 2020) and are generally suitable for military crowdfunding as well.

- Overcoming opposition from the military and the state. Such opposition seems paradoxical, but it does exist. Resistance increases as aid becomes more specific (e.g., field radio stations rather than food), more targeted (e.g., for a specific unit rather than the MoD), or more deeply involved in the process of equipping forces. Volunteer teams engaged in service crowdfunding face the greatest resistance, because:

- Crowdfunding does not adhere to official regulations, and top supply-and-logistics officials (and leaders of potentially crowdfunded units) are not always willing to take responsibility for violating the regulations. Note that the flexibility gained from ignoring them is precisely one of crowdfunding’s main advantages, as it may better meet the real needs of the military (Kashin and Sushensov, 2024).

- Crowdfunding risks the state’s partial loss of control over supplying the military.

- Society may perceive crowdfunding as evidence that the existing military supply system—and perhaps the military as a whole—is ineffective. Such narratives are amplified by anti-Russian propaganda (Troyanovsky, 2022) and are particularly undesirable during mobilization, as they provoke fear of heavy casualties, resistance to conscription, and opposition to the continuation of hostilities. That is why, even if there are problems with supply, military command assures the public that they do not exist or will be quickly resolved (Baglikova, 2022; Surkes, 2023). Yet crowdfunding also masks problems with the official logistics system, permitting it to declare that troops are adequately supplied, without specifying by whom.

- Supply and logistics officers may see crowdfunding as reflecting a negative assessment of their own work.

- Crowdfunding campaigns are often conducted in legal gray areas. This increases their flexibility (e.g., cryptocurrencies facilitate international and anonymous donations) but also creates risks of legal violations.

- Material resources gathered by volunteers are less protected from sabotage than resources provided by the official system, and their quality and compliance with military requirements are not sufficiently controlled (Halpern, 2023). This jeopardizes the safety of those using such supplies.

The Russian state has become more suspicious of private and volunteer organizations’ support of the military since the June 2023 Wagner PMC rebellion. In our opinion, the government should dismiss these fears and welcome crowdfunding as an expression of patriotism that complements the official supply system, increasing its flexibility and capabilities. The military logistics system of Russia—and of other countries, as demonstrated by Israel’s October 2023 mobilization (Surkes, 2023)—cannot quickly adapt to the constantly changing conditions of modern warfare. It should be made more flexible (including through greater autonomy for its administrators and for field commanders) in order to integrate crowdfunded supplies. Effectiveness of cooperation with crowdfunding volunteer organizations should perhaps become a measure of the official system’s performance. This would essentially mean encouraging military command to cooperate with volunteers and gently integrate them into the official logistics system (as the Ukrainian army did).

- Measures against practices that generate public mistrust of military crowdfunding, including the fraudulent collection of funds (Riley, 2022; Smith, 2022) or their misuse partially or fully for purposes other than those that were declared. Involuntary donations (e.g., forced by one’s employer) are another harmful practice, as they spark disaffection with crowdfunding and with the government that permits them, and are exploited by anti-Russian propaganda. The government must take tough measures against individuals and legal entities that employ such practices.

- Countering enemy attempts to obstruct patriotic crowdfunding, threaten fundraisers, damage their physical or digital infrastructure, destroy collected resources, etc.

Guerrilla Crowdfunding

There are two varieties of guerrilla crowdfunding:

- An open version that is publicly for support of the army that the potential donors’ state is fighting against. Such campaigns may be launched if enough people living in that state want the opposing country to win. Despite state censorship, information about such campaigns can be communicated via the Internet, and modern payment technologies (including cryptocurrencies) permit transfers even if official financial channels are shut. This model requires maintaining a relationship with the enemy state’s population, information platforms protected from the enemy’s security services, and a covert payment infrastructure.

- A hidden version, with false declarations of the fundraising’s purpose, i.e., a military version of the civil scam crowdfunding (Lee et al., 2022)). (Often, ostensible support of the target state’s armed forces.) Even if exposed, such schemes undermine the confidence of the target state’s population in crowdfunding. They may involve fake versions of the enemy’s digital fundraising platforms, and may be carried out by non-state actors (e.g., volunteer hackers).

Funds raised in the enemy state may remain there to support subversive operations or—under conditions of sanctions or export restrictions imposed against the campaigning state—to purchase goods through front companies.

Traitorous Crowdfunding

Traitorous crowdfunding is guerrilla crowdfunding targeted against, rather than conducted by, one’s state. Donors may be voluntary (in support of open crowdfunding) or random (if tricked into supporting hidden crowdfunding). This distinction is important for determining their responsibility for financially supporting the enemy army.

The state must counter traitorous crowdfunding by taking, inter alia, the following steps:

- Punishment of support for the enemy’s fundraising campaigns (this work is currently underway in Russia (Sovina, 2024)).

- Informing the population about the consequences of participation in traitorous crowdfunding.

- Teaching people to recognize the enemy’s hidden crowdfunding.

- Identifying and eliminating structures that fundraise for the enemy.

- Identifying, disabling, and destroying the infrastructure used by enemy crowdfunding.

- Confiscating collected funds, including by hacking the digital infrastructure used to raise them. Seized funds can be used to support one’s own armed forces, or returned to the donors if they were deceived.

Enemy Crowdfunding

Enemy crowdfunding is the enemy’s patriotic crowdfunding. Russia might obstruct enemy crowdfunding, inter alia, through sabotage of the crowdfunding infrastructure, sabotage of the organizations and persons engaged in fundraising, destruction of the collected resources, and psychological measures to discourage potential donors from participating in fundraising campaigns for their armed forces.

The latter may include the popularization of views that: 1) funds are spent ineffectively and misappropriated, fundraising campaigns are fraudulent or coercive, etc.; 2) the military’s inability to provide for its soldiers is more a reason to press for an end to hostilities than it is a reason to donate; 3) participants in fundraising are supporting an incompetent regime and artificially prolonging the war, leading to unnecessary human losses on their own side (this argument can be instrumental in the case of Ukraine overusing forced mobilization); 4) people already finance the army with their taxes; 5) after defeat the victors will prosecute those who participated in fundraising.

* * *

Crowdfunding is more than a tool for resource collection. It also serves as the basis for alternative supply chains for the army, which, having engaged non-military and non-state actors, increasingly resemble an ecosystem. Its core consists of the official logistics system, now supported by the government budget and also by donations from individuals, corporations, and foreign actors. Around this system are arrayed various independent (but sometimes cooperating) organizations: private military companies, informal volunteer teams, foundations, specialized business units, etc. The resulting network transcends the boundaries of traditional army sustainmemt by diversifying the sources and models of supply. By meeting a wider range of the troops’ specific needs it increases the quality and flexibility of supplies and stimulates the emergence of new producers of military equipment.

Cooperation between volunteers and the official logistics administration combines the advantages of different supply models and provides volunteer organizations with access to the official system. But it should not subordinate volunteers to the military’s full control, as this would limit crowdfunding’s advantages in flexibility.

Military crowdfunding and fundraising management should not be limited to collecting donations from patriotic citizens but should also implement tools for rasising funds from supporters among the enemy’s population. Strategies should be developed to disable the enemy’s potential for military crowdfunding campaigns. Extensive use of digital tehnologies for military crowdfunding to reach the enemy’s population makes it differ considerably from civic crowdfunding and historical fundraising campaigns for the army (Danilov, 2019).

Asmolov, G., 2022. The Transformation of Participatory Warfare: The Role of Narratives in Connective Mobilization in the Russia-Ukraine War. Digital War, 3, pp. 25-37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-022-00054-5

Baglikova, I., 2022. Тихая помощь. Почему в Петербурге о раненых заботятся тайно [Quiet Help. Why the Support to the Wounded Soldiers in St. Petersburg Is Secret]. Fontanka, 1 November. Available at: https://www.fontanka.ru/2022/11/01/71784956/ [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Boichak, O. and Asmolov, G., 2021. Crowdfunding in Remote Conflicts: Bounding the Hyperconnected Battlefields. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research. Available at: https://spir.aoir.org/ojs/index.php/spir/article/view/12147 [Accessed 1 July 2024]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2021i0.12147

Boichak, O. and Hoskins, A., 2022. My War: Participation in Warfare. Digital War, 3, pp. 1-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-022-00060-7

Champion, M. and Krasnolutska, D., 2023. Ukrainians Dig Into Their Own Pockets to Fund Everything from Drones to Mortars. Bloomberg, 21 February. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2023-ukraine-local-fundraising-helps-pay-cost-of-war/ [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Danilov, V. N., 2019. Мобилизация денежных средств населения в годы Великой Отечественной войны: практика Саратовской области [Civic Crowdfinding during Great PatrioticWar: The Saratov Region’s Practices]. Izvestia Saratovskogo universiteta. New Series: History, International Affairs, 19(3), pp. 387-395.

De Crescenzo, V., Botella-Carrubi, D., and Rodríguez García, M., 2021. Civic Crowdfunding: A New Opportunity for Local Governments. Journal of Business Research, 123, pp. 580-587. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.021

Domínguez-Borrero, C., Cordón-Lagares, E., and Hernández-Garrido, R., 2020. Analysis of Success Factors in Crowdfunding Projects Based on Rewards: A Way to Obtain Financing for Socially Committed Projects. Helyon, 6(4), e03744. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03744

Grove, N. S., 2019. Weapons of Mass Participation: Social Media, Violence Entrepreneurs, and the Politics of Crowdfunding for War. European Journal of International Relations, 25(1), pp. 86-107. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117744867

Halpern, S., 2023. IDF Receives Dozens of Shipments of Defective Protective Vests. The Jerusalem Post. Available at: https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/defense-news/article-768692 [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Hawser, A. 2022. Ukraine’s Army of Drones Crowdfunding Campaign. Defence Procurement International, 4 October. Available at: https://www.defenceprocurementinternational.com/features/air/ukraines-army-of-drones-crowdfunding-project [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Kashin, V.B. and Sushentsov, A.A., 2024. Warfare in a New Epoch: The Return of Big Armies. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(1), pp. 32-56. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-1-32-56

Khoma, N., 2023. Crowdfunding and Fundraising in the Peacebuilding System: Ukraine’s Case. Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review, 20(1), pp. 53-75. DOI: https://doi.org/10.47459/lasr.2023.20.3

Kotliarov, I.D., 2024. Краудфандинг как инструмент финансирования: концептуальный анализ [Crowdfunding as a Financial Tool: A Conceptial Analysis]. Mirovaya ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 68(8), pp. 28-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20542/0131-2227-2024-68-8-28-36.

Kots, F., 2024. “Это новый Т-34”: Как гениальный российский дрон стал хозяином Днепра, убийцей “Абрамса” и ужасом ВСУ [“This is a New T-34”: How a Smart Drone Mastered the Dniepr, Killed Abrams and Horrified the UAF]. Komsonolskatya pravda, 8 October. Available at: https://www.kp.ru/daily/27644/4995161/ [Accessed 11 November 2024].

Langley, P., 2016. Crowdfunding in the United Kingdom: A Cultural Economy. Economic Geography, 92(3), pp. 301-321. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1133233

Lee, S., Shafqat, W., and Kim, H-c., 2022. Backers Beware: Characteristics and Detection of Fraudulent Crowdfunding Campaigns. Sensors, 22(19), 7677. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/s22197677

Loh, M., 2024. Ukraine’s Front-Line Fighters and dDonemakers Are Trying to Crowdfund Their Way to Russia’s Defeat through Cheap Strikes. Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/ukraine-dronemakers-war-unwinnable-dirt-cheap-crowdfunding-veterans-civilians-russia-2024-12 [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Marsh, N., 2023. Responding to Needs: Military Aid to Ukraine during the First Year after the 2022 Invasion. Defense & Security Analysis. 39(3), pp. 329-352. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2023.2235121

Méheut, C., and Mitiuk, D., 2024. Crowdfunding, Auctions and Raffles: How Ukrainians Are Aiding the Army. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/07/world/europe/ukraine-war-donations-crowdfunding.html [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Nilsson, P.-E. and Ekman, I., 2024. “Be Brave Like Ukraine”: Strategic Communication and the Mediatization of War. National Security and the Future, 25(1). Available at: https://www.nsf-journal.hr/NSF-Volumes/Focus/id/1496. DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.25.1.2

Paschen, J., 2017. Choose Wisely: Crowdfunding through the Stages of the Startup Life Cycle. Business Horizons, 60(2), pp. 17-188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.11.003

Redko, O., Moskalenko, O., and Vdodovych, Y., 2022. The Role of Crowdfunding Systems during Crises and Military Actions. Baltic Journal of Economic Studies, 8(4), pp. 117-121. DOI: https://doi.org/10.30525/2256-0742/2022-8-4-117-121

Riley, T., 2022. Cybercriminals Are Posing as Ukraine Fundraisers to Steal Cryptocurrency. Cyberscoop, 10 March. Available at: https://cyberscoop.com/cybercriminals-are-posing-as-ukraine-fundraisers-to-steal-cryptocurrency/ [Accessed 11 November 2024].

Roblin, S., 2023. Pilot Explains How Ukraine’s Crowdfunded ‘Army of Drones’ Saves Lives. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sebastienroblin/2023/05/02/interview-pilot-explains-how-ukraines-crowdfunded-army-of-drones-saves-lives/ [Accessed 21 March 2024].

Shakirov, А., 2024. Путин сообщил, что волонтёры собрали на нужды ВС России 11 миллиардов рублей [Putin Said that Volunteers Had Raised 11billion rubles for the Russian Army’s Needs]. Komsomolskaya pravda. Available at: https://www.kp.ru/online/news/5657139/ [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Shchipansky, P.V., Leontovich, S.P., and Sotnik, S.V., 2022. Міжнародна допомога партнерів як одна з економічних складових перемоги [Foreign Parters’ Support as an Economic Factors of Victory]. Nauka і oborona. Available at: http://nio.nuou.org.ua/article/view/270963 [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Schneor, R., 2020. Crowdfunding Models, Strategies, and Choices Between Them. In: R. Shneor, L. Zhao, and B.-T. Flåten (eds.) Advances in Crowdfunding. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 21-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46309-0_2

Skorobogaty, P., 2022. Два миллиарда рублей на помощь фронту [Two Billion Rubles for the Front]. Expert, 41, pp. 48-50.

Smith, Q., 2022. Scam of the Month: Ukraine Donation Scam. Washington University in St. Louis, 30 March Available at: https://informationsecurity.wustl.edu/scam-of-the-month-ukraine-donation-scam/ [Accessed 11 November 2024].

Sovina, М., 2024. На россиянина завели дело о госизмене за перевод криптовалюты ВСУ (A Russian Was Suited for Transferring Cryptocurrency to the UAF]. Lenta.ru. Available at: https://lenta.ru/news/2024/09/18/na-rossiyanina-zaveli-delo-o-gosizmene-za-perevod-kriptovalyuty-vsu/ [Accessed 9 November 2024].

Spansvoll, R., 2024. The Weaponisation of Social Media, Crowdfunding and Drones: A People’s War in the Digital Age. The RUSI Journal, 169(1-2), pp. 46-60. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2024.2350478

Stewart, P.H., 2015. Ukraine: A War Funded by People’s Donations. Aljazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2015/4/21/ukraine-a-war-funded-by-peoples-donations [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Surkes, S., 2023. Army Launches Hotline for Reservists Seeking Equipment, Food. The Times of Israel. Available at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/army-launches-hotline-for-reservists-seeking-equipment-food/ [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Troyanovsky, A., 2022. Drones. Crutches. Potatoes. Russians Crowdfund Their Army. The New York Times, 28 May Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/28/world/europe/russian-soldiers-military-supplies.html [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Wenzlaff, K., 2020. Civic Crowdfunding: Four Perspectives on the Definition of Civic Crowdfunding. In: R. Shneor, L. Zhao, and B.-T. Flåten (eds.) Advances in Crowdfunding. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 441-472. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46309-0_19

Wood, G. R., 2022. What Role for Crowdfunding Defense in Ukraine? Small Wars Journal. Available at: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/what-role-crowdfunding-defense-ukraine [Accessed 1 July 2024].

Yevtodyeva, M. G., 2023. Западная военная помощь и передачи вооружений Украине в 2022-начале 2023 г.: ключевые тенденции [Western Military Assistance and Arms Transfers to Ukraine in 2022–early 2023: Key Trends]. Pathways to Peace and Security, 1, pp. 11-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20542/2307-1494-2023-1-11-30

Zarembo, K., Knodt, M., and Kachel, J., 2024. Smartphone Resilience: ICT in Ukrainian Civic Response to the Russian Full-Scale Invasion. Media, War & Conflict, 18 March. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/17506352241236449