The ease of transportation and communication in the modern world makes it possible to quickly deliver potential migrants to countries that they previously could only see on their television screens, hear about from family and friends living and working there, or read about in glossy magazines. A new era has dawned, different from anything humanity has ever experienced, and as the world becomes increasingly open to migration, the seeming simplicity of changing status, workplace and place of residence becomes all the more tempting. Unfortunately, ‘migration without borders’,[1] once regarded as a promising strategy for the future, is increasingly viewed an undesirable outcome by a significant number of people in host countries, and migrants can expect to find solidarity mainly among fellow migrants and left-wing parties.

Freedom of movement and freedom to choose a place of residence can be ranked among the category of freedoms which, as part of the Global Commons, have been restricted to varying degrees at the level of communities, states, and international associations. Such restrictions have produced and will continue to produce a variety of migration conflicts both at the level of migration within countries and international migration, which can be accounted for by differences in economic development, environmental situation, armed conflicts, and demographic pressure/depopulation, as well as other factors. In these circumstances, restrictions on migration in the origin and host countries and regions may be justified by the interests of the countries themselves or their governments, but in reality, such restrictions are not insurmountable even under authoritarian and totalitarian systems.

In economically developed countries with aging populations that have been taking in migrants for a while now, right-wing parties advocating greater restrictions on migration are gaining more supporters now, despite the fact that both the governments and the expert community that influences migration policy recognise that migration is an important resource (in economic, demographic, and geopolitical terms). The explosive growth in the number of refugees in 2015 served as a catalyst for this process in Europe. Back then, the countries of the Visegrad Group – Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary – gradually came to an outright reject of the mandatory European quotas and redistribution of refugees within the EU,[2] while the UK’s exit from the EU following the 2016 referendum was, among other things, due to the British being reluctant to provide benefits and social housing to immigrants who have lived in their country for less than four years.[3]

The enthusiasm of EU residents, who welcomed the refugees and, in 2015–2016, offered remarkable examples of solidarity with them,[4] gradually faded, and by 2017–2018 gave way to fears that their excessive numbers had become a challenge to the established pan-European migration system. The real state of politics today includes the fact that Alternative for Germany is making a serious bid to become the third most influential party in the country,[5] Lega Nord (the Northern League) in Italy gained 17.5% of vote in the March 4, 2018, elections and became one of the two parties of the ruling coalition,[6] and the Austrian Freedom Party was involved in forming the government in 2017.[7] The growing popularity of nationalist parties and slogans and the support of a significant share of voters for restrictions on migration are not a purely European development, as is clear from the victory of Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election on a platform of tighter migration policy and the election of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi[8] in 2014, who is considered a leader of the ‘Saffron’ Indian nationalists, who believe that Muslims have no place in India and openly declare in the slogan of their party that nationalism is ‘our inspiration’.[9] This con.rms that the increased popularity of nationalist parties and slogans and the support by much of the constituency of restrictions in migration policy is not a purely European development.

Despite the fact that parties advocating more restricted migration policies are gaining popularity across the world, the possibility of free movement in and of itself remains an undisputed value,[10] and host countries use it to derive considerable economic benefits, overcome their demographic challenges, and strengthen their geopolitical influence. The equality of human society, implied by the idea of Global Commons, also means equal access to global goods and the right to migrate.

Migrants in Russia: A Wall of a Doubled Alienation

Over the past decade, the external labour migration to Russia has undergone significant changes that directly affect relations between Russians and migrant workers from other countries[11]: instead of residents of large cities, people from small towns and villages are now coming to Russia; the education level of migrants is low as schools are few and far between in rural areas; most new migrants are poorer than in previous years; the cultural differences between the newly arriving migrants and Russians are growing, including in terms of religion and language; the share of migrant workers from Central Asia is growing, and they have begun to form communities in Russia; more female migrants and migrants with families are also coming to Russia.

The already tangible lack of unity in the Russian society is further aggravated by distrust between migrants from other countries and Russians. Even though such distrust rarely escalates into open hostility, one can speak of the parallel existence of the two worlds: the world of Russians and the world of migrants. Mutual distrust and growing alienation go hand-in-hand with the emergence of boundaries that resemble glass walls through which both sides can see each other but rarely interact.

The Glass Wall Built by Foreign Migrant Workers

The mutual assistance that foreign migrant workers (especially from Central Asia) in Russia provide to each other has over time led to a number of institutions that formed the basis for ‘parallel’ migrant communities springing up in Russian cities.[12] Some examples follow below.

- There is a network of ethnic eateries (Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Tajik) not only on central streets of Russian cities, such as Chaykhona No. 1, but unassuming backstreet dives that cater mostly to migrants.

- There are also athletic clubs where migrant coaches give classes in various sports and martial arts to migrant students (typically, Kyrgyz).

- A network of migrant outpatient clinics has emerged in Moscow, where doctors (both Russian citizens of foreign origin and migrant workers) provide medical services to migrant workers and use the languages of Central Asian countries to communicate. Access to such medical centres is open to Russians as well, but migrant workers form the bulk of their patients.

- Informal migrant services have been created to address issues such as registration at a place of residence, obtaining work permits, and other issues that every labour migrant in Russia is confronted with. Such services are often based on corrupt and even criminal ties between shady dealers from diaspora communities and corrupt representatives of the Russian law enforcement agencies and authorities.

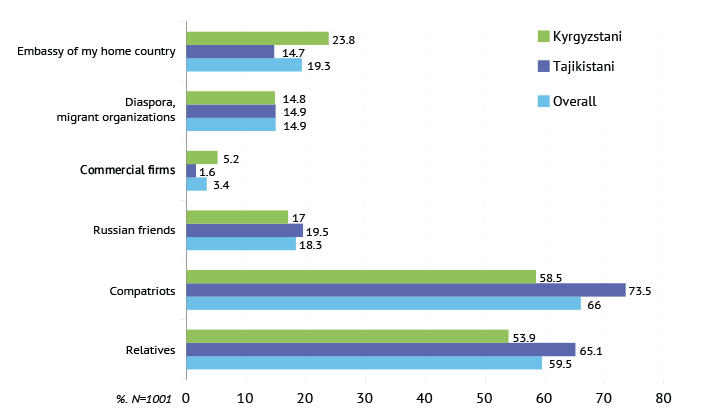

THE DISTRIBUTION OF RESPONDENTS BY WHERE THEY SEEK HELP, 2016[13]

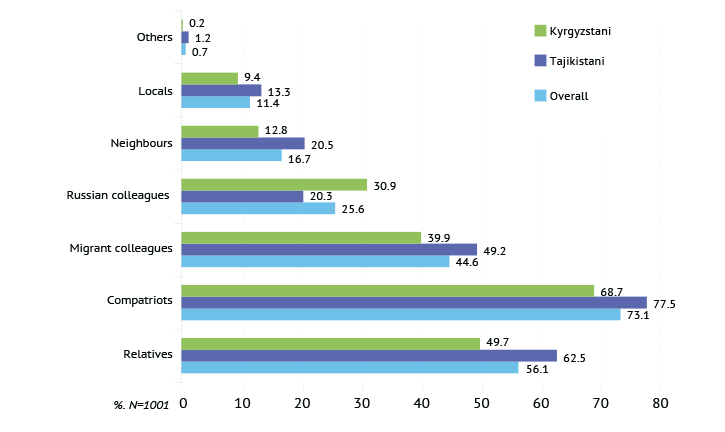

The emergence of parallel migrant communities in Russian society represents a major challenge for the future of Russia. The crisis of trust in Russian society is further exacerbated by feelings of alienation between foreign migrant workers and local residents. Long-term studies of migration to Russia[14] show that migrant workers count on help only from family and friends. This is especially true of migrant workers from Central Asia. A 2016 survey conducted among migrant workers from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan revealed that in the overwhelming majority of cases they rely on help from family, friends, and fellow migrant workers from the same country of origin. Over decades of living in Russia, migrant workers almost never have face-to-face interactions with Russians as part of their daily lives. From year to year, migration studies in Russia show minimal levels of interaction with the locals.

THE DISTRIBUTION OF RESPONDENTS BY WHO THEY INTERACT WITH, 2016[15]

Even within the Muslim community, interactions between Muslim Russians and Muslim migrant workers from Central Asia are limited. Although the Tatar Muslim community and the Caucasus Muslim community welcome their fellow believers from Central Asia and seek closer relations with them, complete unity is a distant prospect.[16] Interestingly, even the language of sermons in mosques located in big Russian cities changed from Tatar to Russian, as migrant workers from Central Asia, who now make up most of the ummah, do not understand the Tatar language in which sermons used to be delivered. Some migrant workers from Central Asia have introduced elements of paganism into traditional Islam, such as ‘charging’ water and using it for medicinal purposes (which is popular with part of the Kyrgyz community), new rituals that are at odds with the canons of Islam (divorce over the phone by repeating the word ‘talaq’ (divorce) three times), and entering into marriages with the help of mediators without an official ecclesiastical title despite the fact that one or both partners are officially married back home in Central Asia. This creates mistrust and even some division between Russian Muslims and Muslim migrant workers from Central Asia.

Radicalization of migrant workers, even those who eventually obtain a residence permit or Russian citizenship, is one of the consequences of such disunity. Migrant workers and Russians of foreign origin – who are humiliated by xenophobia, do not have much education, and find themselves isolated from the Russian society for whose benefit they work tirelessly – provide fertile ground for spreading radical ideas, recruiting for terrorist organizations, and enlisting in terrorist attacks. On April 3, 2017, there was a terrorist attack in the St. Petersburg underground.[17] According to the Russian Investigative Committee, a suicide bomber by the name of Akbarjon Jalilov, a Russian citizen since 2011 of Uzbek origin and a native of Kyrgyzstan, was responsible for the blast that killed 16 and injured 87.

The Glass Wall Built by Russians

Fear of migrants is the main ‘building material’ for the wall from the part of Russians. While its level had declined enormously by 2018,[18] it remains fairly high. According to the Levada Center[19], in 2017, the share of Russians in favour of limiting the number of people of other ethnic backgrounds living in the country reached a low of 54% of 13 years of sociological surveys, compared to 70% in 2016 and 81% in 2013. Attitudes towards members of the majority of ethnic groups living in Russia have improved. In 2013, 45% of the respondents believed that it was necessary to limit the presence of people from Central Asia in Russia. By 2014, the figure had dropped to 29%, reaching 22% in 2017. Similar dynamics can be observed with regard to Roma, Chinese, Jews, Vietnamese, and Ukrainians. In 2017, the number of the Russians against limiting the number of residents of any non-Russian nations in the country increased to 28%, compared to 11% in 2013 and 20% in 2016.

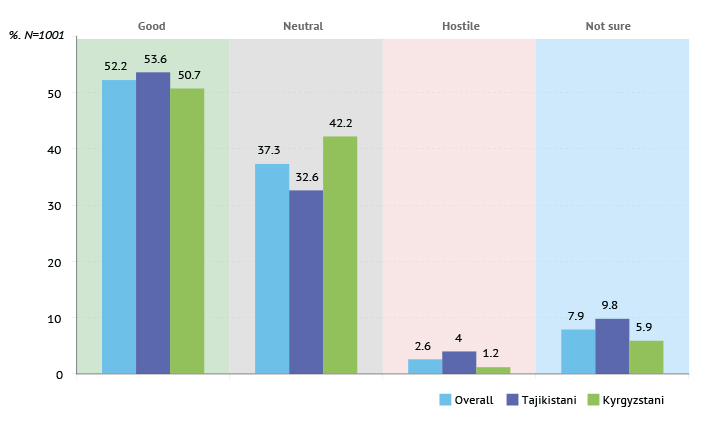

LOCAL PEOPLE’S ATTITUDES TOWARDS MIGRANTS FROM TAJIKISTAN AND KYRGYZSTAN, 2016[20]

Despite the improved attitudes towards migrants, a majority of Russians (58%) in 2017 believed that their entry into the country should be limited, a 10% decline from 2016. Attitudes of Russians to migrants already living in the same cities as them was mostly neutral in 2017 with 60% of respondents saying they have no negative feelings about it. At the same time, 8% of respondents said they have feelings of respect and sympathy for migrants, 28% expressed annoyance and hostility, and 2% – fear. Studies by the Migration Research Center also show that Russians are considered fairly open to migrants, and this is according to migrant workers from Central Asia.

Lack of comprehensive and specially funded adaptation and integration programmes for including migrants in the social and cultural life of the Russian society and providing general assistance to them in Russia also contributes to building barriers between the local Russian population and migrants. In Russia, there are only isolated elements of an incomplete system to promote

integration, such as free education for children of migrants at Russian schools, free emergency medical care, and free maternity hospital services for migrant women. These elements are not interconnected and are not part of the country’s migration policy. Moreover, they are not specifically aimed at reducing disunity between migrants and Russians.

Back when the Federal Migration Service of Russia was still in existence and to this day, the practice has been primarily to engage diaspora associations as the sole representatives of migrant communities in the public dialogue and cooperation with authorities of all levels. On the one hand, this decision excludes Russian NGOs that provide direct assistance to migrants of various categories from full-.edged cooperation with the authorities, but, on the other hand, it involves in migrant adaptation and integration ethnic and cultural associations (diasporas) that were originally created not for migrants’ adaptation and integration, but preservation of the national culture, traditions, and native language. Round tables with the participation of ethnic and cultural associations (ECAs) held by government officials and the involvement of such ECAs in the work of regional public chambers and the Civic Chamber of the Russian Federation is important and necessary, but only minimally effective in integrating migrants. Some diaspora associations monetize their interaction with local authorities, providing migrants with fee-based legalization services. This state of affairs serves only to perpetuate the isolation of migrants in Russian society and complicates their basic adaptation and further integration.

Non-profit Organizations

In the EU and the United States, as well as Southeast Asia, host countries have a large number of NGOs[21] that provide a variety of services to migrants. What sets them apart from Russian NGOs is the fact that they are an integral part of the migration system of their countries and in.uence migration policy in their respective states and regions.

The small number of NGOs[22] that provide the necessary assistance to migrants in Russia for free is due to both weak civil society and the lack of sufficient state funding for NGOs, including think tanks. Temporary projects of international organizations and grants from charitable foundations are too limited and inconsistent to ensure proper functioning and development. In addition, the civil society institutions themselves, as well as volunteering and social responsibility, are not yet fully developed. However, there is a desire to consolidate and unite the efforts of NGOs in the form of creating special NGO networks and public organizations, including the All-Russian Memorial Network Migration and Law, which operates through lawyers[23], and attempts to unite on a broad-based civil platform like the initiative of the 21st Century Migration Foundation[24] in late 2012. Non-pro.t NGOs, such as Civic Assistance, Migration and Law, Sisters and the Ural House, to name a few, are more efficient than others at helping migrant workers. Unfortunately, their effective solutions for Russia have not yet been realized because the Russian state has not ordered the creation of these services that are so vital to helping migrant workers.

In Russia, there are examples of migrant groups self-organizing as non-governmental organizations both for addressing long-term issues and providing relief for the catastrophic consequences of war for refugees. For example, the Forum of Migrant Organizations was created after the collapse of the Soviet Union to address the problems of refugees and internally displaced persons, and one of the many organizations that were part of this network – the Ural House[25] – turned into a public organization that provides high-quality services to migrants at the lowest possible price. It operates according to strict ethical standards that preclude dubious schemes with shady intermediaries and has become a benchmark for the quality of service. The functioning of the Ural House Integrated Support Centre for Migrants makes it possible to simultaneously provide information, legal advice, accommodation, legalization services, and job placement for migrants; maintain feedback with migrants and employers; and create a database of potential migrants from the CIS countries and vacancies in the Sverdlovsk region.

Russia has several large interethnic entities, such as the Federation of Migrants of Russia[26], the Assembly of the Peoples of Russia[27], and the Union of Diasporas of Russia, but their activities do not involve provision of comprehensive direct assistance to migrant workers. Importantly, the migrant organizations that are now helping migrant workers (once united under the auspices of the Forum of Migrant Organizations, such as the Ural House, etc.) initially helped people of different ethnic backgrounds and mixed families leaving for Russia and did not divide migrants along ethnic lines. Disadvantaged migrants have always been for them more than just clients, but also supporters and allies. Precisely this strategy led to the current success of the civil society organizations in Russia when they have to fight for survival. People who found themselves in a new environment and a different country united to address common challenges, realizing what was proclaimed as a goal back in the Soviet Union: a multicultural society in which ethnic background was not important.

Diaspora Organizations

Migrant diasporas in all Russian regions are an unofficial and unstructured assistance organization. There are quite a few of such diaspora organizations registered in various legal forms[28], such as public organizations, ethnic and cultural associations and foundations. However, intermediary and commercial activities account for much of their work. High trust levels shown by migrants with regard to those who speak their native language have in some cases led to legalization schemes through unofficial channels with intermediaries using corrupt connections, relegating legalization services to the shadow economy.

Russian intermediary commercial organizations and NGOs find it difficult to gain the trust of migrants, but diaspora organizations have no problem with that. They speak the same language, so turning a prospective client into an actual client is simple enough for them. When such diaspora organizations deal with social problems of migrants and defend their rights, they succeed while protecting migrant workers from being cheated by unscrupulous employers, helping them escape slave labour and return home, etc. Unfortunately, a significant portion of them work on the market of intermediary services, and even if they call themselves a non-profit organization, they, in fact, are making money off helping migrants. Many diaspora representatives are interested in promoting commercial assistance among migrants, and such fee-based assistance is provided most often through commercial companies that are created to cater to such diasporas.

The diaspora organizations that are trying to provide free social services to migrants remain operational as long as they have funding, such as grant support. As soon as they run out of such funding, their work tapers off and other organizations, trying to fill the niche of the main representative of a particular diaspora in the region quickly push aside the former protagonist. In their rivalry for leadership and clients within the diaspora, those who establish the best contacts with the consulate of the country of origin and the Russian authorities usually have the upper hand, which hampers consolidation of a diaspora. Precisely because the diasporas operate through businesses engaged in fee-based intermediary activities that have their own financial interests, the attempts to unite diaspora organizations have so far been unsuccessful. It is also important to take into account the fact that diasporas are separated regionally, which is not good for unification either.

Activities such as providing free employment services, document issuance, talking with government officials, and defending the rights migrants on a case-by-case basis are carried out haphazardly within diasporas. Not all diaspora organizations use lawyers in their work. As a rule, the leaders have to do the bulk of the work themselves, such as maintaining dialogue with the authorities and speak at conferences. This prevents diaspora organizations from conducting any human rights activities to help migrant workers within the system.

The ‘old diaspora’ organizations have been working in Russia for a long time now and quite intensively, such as the Armenian diaspora, which runs Sunday schools and television broadcasts. The Azerbaijani diaspora also has its own media. These diasporas are headed by rich and influential leaders. However, among migrants from Central Asia, only migrants from the Pamir Mountains have come up with a similarly strong organization.

International Organizations

International organizations, such as International Organization for Migration, International Labour Organization, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Red Cross and Red Crescent, International Centre for Migration Policy Development, etc., do an enormous amount of work to provide information and legal advice, to initiate public and academic discussions about migrant workers’ problems and the help they need, and to share best practices in protecting the rights of migrants in Russia and around the world. International organizations have accomplished much. However, their status allows them to influence the processes of forming systemic protections of migrant workers’ labour rights and improving law enforcement practices, but they cannot participate in them directly. Thus, their role is important, but limited.

International organizations are most effective as coordinators of migration policy, consultants supporting NGO networks, and producers of analytical documents on important matters. As coordinators of new initiatives and best practices, they are effective in building a systemic approach to assist migrant workers. They can also spearhead initiatives to promote solutions to the most challenging problems, such as human trafficking (organizing shelters) and slave labour. In addition, by disseminating the best practices already developed by human rights organizations, NGOs, and commercial organizations, international organizations can help develop the interaction models and spread them across Russia and the world.

Migrant Trade Unions as a Form of Solidarity

Labour migration is seen not only as a globalization trend, but even as an alternative to the class struggle;[29] therefore, the question of the most effective practices that migrant workers can use to protect their labour rights is becoming increasingly important. Studies show that migrants prefer to resolve their problems themselves, so the form of self-organization as trade unions looks most promising and straightforward to them, which is backed up by the existing practice of unions working with foreigners in Russia and around the world. However, trade unions in Russia and the rest of the world play very different roles when it comes to protecting migrant workers’ rights.

For example, in Moscow, the Trade Union of Migrant Workers[30] mediates labour disputes between migrants and their employers and provides high-quality services, information, and counselling to migrants. Its activities are not limited to intermediary services as it also publishes the newspaper Vesti Trudovoy Migratsii (News of Labour Migration) and informs migrants and their leaders about the latest changes in legislation and other developments. The upside of this union is that it managed to demonstrate that trade unions can effectively work with migrants in Russia. Unfortunately, this union has so far been unable to encourage migrant workers to form a large-scale association and has only approximately 35,000 members on its roster.

Officials in Moscow, as the centre of Russia, cannot afford to be overly conservative. The situation in regions is more complicated. Local officials are more conservative, and it is therefore very difficult to create an active trade union there, especially a union for migrants. There were attempts to create unions that are similar to the Migrant Trade Union. However, in the Urals region, for example, they ended unsuccessfully. On the one hand, this was due to the fairly large number of existing intermediary organizations in the region, and, on the other hand, the consolidation of migrants around a trade union was a delicate proposal since each of the diaspora organizations operating in the region pursued its own interest, primarily, financial.There was an attempt to establish a Territorial Trade Union of Employees of Organizations Using Migrant Labour in the Arkhangelsk region in 2008. However, according to the Sova Centre[31], local authorities opposed the activities of this trade union, and it essentially closed down.

Not all countries have functioning migrant trade unions. In some states the authorities do not allow such unions or break them up and shut them down. For example, a labour union of migrants in South Korea was disbanded.[32] There is the All-Ukrainian Union of Migrant Workers in Ukraine and Abroad,[33] which works with its members living and working outside the country. Russian trade unions that have their origin in the Soviet unions, as a rule, oppose labour migration and the notion that Russia needs migrants. Such trade unions can hardly be considered partners when it comes to protecting migrant workers. Migrants never join these unions; such unions do not work with migrants or their employers. Their position as de facto opponents of cooperation with migrants has remained unchanged for quite a long time now.

In other countries, solidarity with migrant workers is based on a more comprehensive and broader foundation. For example, in the United States, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations[34] (AFL– CIO) has a partnership agreement with the network association of temporary workers – the National Day Laborer Organizing Network.[35] This network operates through job centres throughout the US and works with migrant workers who do not have a full-time job and are often employed without labour contracts. This association is not a trade union in the conventional sense, since it does not engage in collective bargaining. However, temporary workers use it to determine the rules and terms of employment, in particular, the minimum wage below which they cannot go. Most of the temporary workers and the majority of the job centre employees are immigrants; therefore, they develop political, legislative, and legal rules that also affect migrants. There is also a partnership with another network job centre called Interfaith Justice.[36] The AFL–CIO Executive Committee in Chicago adopted a resolution that allows job centres to join trade unions at the local and state levels as public partners (Central Labor Councils/ State AFL–CIO). There is a practice of preparing migrant workers for life far from home by involving them in union activities even before they leave the country to migrate.[37] For example, Belgian unions promote dialogue with trade unions in the countries of origin by organizing seminars and setting up information centres, while French trade unions have offices in the countries of origin of migrants in order to provide information on their rights and union membership.

Trade unions in countries of origin are also interested in maintaining contacts with members of their associations who have gone abroad, such as the National Union of Autonomous Trade Unions of Senegal (UNSAS), the Dominican National Labour Confederation (Confederación Nacional de Trabajadores Dominicanos, CNTD), the General Federation of Nepalese Trade Unions (GEFONT) with branches for Nepalese workers who work in India, the Ceylon Workers’ Congress of Sri Lanka, the Moroccan Labour Union (Union Marocaine du Travail, UMT), and the General Confederation of the Portuguese Workers (CGTP–IN), which enlists migrants in the union in the countries of origin. Trade union associations in the countries supplying labour force develop policy measures to help migrant workers when they return to their respective home countries.The Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC)[38] operates in the US and Mexico ensuring the protection of agricultural workers and their participation in the union. In Mexico, FLOC advocates for the newly acquired rights of workers that farmers bring to the United States. A global union federation – the Union Network International (UNI)[39] – issued a UNI passport to help migrant workers protect their trade union rights and receive assistance when moving from country to country. The UNI passport makes it possible for the service workers[40] to:

- join any of the more than 900 trade unions around the world that are UNI members;

- obtain support and assistance from a local union in a country of destination that is a UNI member;

- get familiar with the functioning of a local trade union and also sign up for the mailing list to receive information materials and invitations to cultural and political events;

- participate in the activities of a local trade union, for example, in groups dealing with speci. c professional issues or organizing training;

- obtain access to information about working conditions, banking and tax systems, housing conditions, school facilities, medical care, and the pension system;

- get legal advice on employment issues, employment agreements, local labour laws, and collective agreements;

- obtain legal support in dealing with the employer.

Getting new members aboard is an important rationale behind enlisting migrant workers in unions. Labour market reforms in developed countries have led to a reduction in the number of trade unions, an increase in union members’ average age, and a decrease in the number of trade unions in highly active industries. Given these circumstances, the search for new members in areas outside the scope of trade unions, including areas where migrant workers are employed, becomes important for strengthening the labour movement. For instance, in Switzerland, in the Industry and Construction Trade Union (GBI), the number of foreign-born workers already makes up more than half of its members. Meanwhile, Portuguese migrants join unions in the UK. Many new members who have joined the AFL–CIO after an extended period of shrinking union membership in the United States are migrant workers from Latin America and the Caribbean.

German trade unions cooperate with Polish unions in the construction industry and agriculture. They have offices in Warsaw where members can get information about employment terms and conditions and labour rights in Germany. Potential migrants in Poland are invited to join the union before leaving the country. The unions support bilateral and trilateral agreements between the migrants’ countries of origin and destination which recognize the validity of joint union membership in both countries so that German unions can help migrant workers without them having to join their trade union.

In September 2004, the German Trade Union for Building, Forestry, Agriculture and the Environment (IG BAU) created the European Migrant Workers Union[41], which defends the interests of seasonal workers, especially migrant workers in the construction industry and agriculture. The union provides legal assistance, advice, and support in the event of illness or accident, ensures the receipt of the agreed amount of compensation, and helps improve housing conditions. In the US, a number of Boston-based unions have developed the Immigration Rights Advocacy, Training and Education Project (RATE) with an eye towards uniting migrant workers, providing information and legal assistance and help in creating workers’ committees, as well as further training of trade union activists. Even domestic servants, who are isolated from the host society and are subject to exploitation like no other workforce, such as the South African Domestic Service Allied Workers Union,[42] are making efforts to unite. Unionizing domestic servants requires innovative strategies and approaches, as well as providing them with a wide range of services, such as help overcoming low self-esteem and developing worker consciousness.

Unfortunately, the above-mentioned practices of working with foreigners on the basis of trade unions still have very limited prospects for being implemented in Russia, which is due to the conservative stance of Russian trade unions and legal restrictions. However, efforts to protect migrant workers’ labour rights are already underway as part of the EAEU practices and have the potential to turn the situation around fairly quickly.

***

Summing up, the conclusions are as follows:

- Despite the increasing popularity of right-wing parties in recent years and stricter migration policies in key host countries, institutions supporting migrants, such as NGOs, trade unions, including migrant trade unions, international organizations, and associations dealing with migration policies and supporting migrants, to name a few, are strong enough to maintain the high levels of solidarity exhibited by host societies towards migrants.

- In Russia, civil society institutions operating in the migration sphere received a powerful leg up in the 1990s but largely (though not definitively) exhausted their potential by 2018. In this regard, migrants in Russia, as corroborated by studies, have minimal chances of getting support since integration and adaptation efforts on behalf of the state have been reduced to a minimum and the situation is unlikely to change any time soon.

- The level of solidarity with migrants is fairly low in Russia today. However, civil society institutions have, since 1991, gained enough experience and developed practices to be able to effectively support migrants in Russia. As such, when migration policy is updated and its humanitarian component is improved, Russia will be well-positioned to enhance solidarity with migrants within its society.

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai International Discussion Club

[1] See the collective study arguing the economic advantages of such a development strategy: ‘Migration without Borders: Essays on the Free Movement of People’, 2009, edited by Antoine Pecoud and Paul de Guchteneire, UNESCO.

[2] ‘Tsentrobezhenskie Tendentsii. Lideram Evropeiskikh Stran ne Udaetsia Dogovorit’sia o Tom, Chto Delat’ s Migrantami’ [Centrigugal Trends on Migrant Issue: European Leaders Fail to Agree on Migrant Policies], 2018, Korresant, June 25. Available from: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3668062

[3] ‘The Four Key Points from David Cameron’s EU Letter’, 2015, BBC News, November 10. Available from: https:// www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-34779250

[4] Bershidsky, L, 2017, ‘One Million Refugees Came. Here’s What Happened Next’, Bloomberg, September 18. Available from: https://inosmi.ru/politic/20170919/240316593.html

[5] Kartsev, D, 2018, ‘Tret’ia Fol’kspartai. Pochemu «Al’ternativa dlia Germanii» – eto Nadolgo’ [Volkspartei No.3: Why Alternative for Germany Is Here to Stay], Carnegie, May 17. Available from: https://carnegie.ru/ commentary/76183

[6] Dunaev, A, 2018, ‘Liga u Vlasti. Zhdet li Italiiu Katalonskii Stsenarii’ [The League Has Come to Power: Is Italy Up For the Catalonian Scenario?], Carnegie, June 8. Available from: https://carnegie.ru/commentary/76554

[7] Klimovich, S, 2017, ‘Pravee, Ul’trapravee. Chto Oznachaet Novoe Pravitel’stvo Avstrii dlia Rossii i ES’ [To the Right and Ultraright: The Meaning of the New Government in Austria for Russia and the EU], Carnegie, December 18. Available from: https://carnegie.ru/commentary/75040

[8] Mirzayan, G, 2014, ‘Prem’er iz Trushchob’ [The Slumdog Prime], Expert, no. 22 (901), May 26. Available from: http://expert.ru/expert/2014/22/premer-iz-truschob/

[9] Strokan, S, 2014, ‘Kasta Natsionalistov. Vlast’ v Indii Perekhodit k «Bkharatiia Dzhanata Parti»’ [The Nationalist Caste: The Bharatiya Janata Party Comes to Power], Kommersant, May 15. Available from: https://www. kommersant.ru/doc/2470280

[10] For instance, the EU Treaty provides for freedom of movement for migrant workers from the EU states (although temporary measures to restrict this freedom for the citizens of states that have recently acceded the EU or are in the process of acceding are also allowed), prohibits any discrimination of such workers based on nationality in the sphere of employment and other working conditions, including social security. Migrant workers enjoy the overall protection provided by the Organization of American States (OAS), which adopted the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man of 1948 (OAS, 1948) and the 1969 American Convention on Human Rights (Pact of San Jos.) (OAS, 1969), which guarantees freedom from discrimination. The Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union proclaims, as one of the four freedoms, the freedom of movement of EAEU nationals within the countries of this association. (See: ‘Handbook on Establishing Effective Labor Migration Policies in Countries of Origin and Destination’, 2006, Vienna, Geneva: OSCE-IOM-ILO, p. 37.)

[11] Zaionchkovskaia, ZA, Tiuriukanova, EV & Florinskaia IF, 2011, ‘Trudovaia Migratsiia v Rossiiu: Kak Dvigat’sia Dal’she’ [Labour Migration to Russia: What to Do Next?], Migration Barometer of the Russian Federation, Special Reports Series, Moscow, MAKS Press.

[12] Demintseva, EB & Peshkova, VM, 2014, ‘Migranty iz Srednei Azii v Moskve’ [Migrants from Central Asia in Moscow], Demoscope Weekly, no. 597-598.

[13] Poletaev D., Nasritdinov E., Olimova S. Analiz konyunktury rynka truda v RF v celyah ehffektivnogo trudoustrojstva trudyashchihsya migrantov iz KR i RT [‘Analysis of Labour Market in Russia in Terms of Efficient Employment of Migrant Workers’]. Bishkek, 2016.

[14] Zaionchkovskaia, ZA, Poletaev, DV, Florinskaia, IF, Mktrchian, NV & Doronina, KA, 2014, ‘Zashchita Prav Moskvichei v Usloviiakh Massovoi Migratsii’ [Protection of Rights of Moscovites in the Face of massive Influx of Migration], Moscow, М.: Commissioner for Human Rights in Moscow, Centre for Migration Studies; Mukomel, VI, 2012, ‘Transformatsiia Trudovoi Migratsii: Sotsial’nye Aspekty’ [Transformation of Labour Migration: Social Aspects], Rossiia Reformiruiushchaiasia, Yearbook, no. 11, ed. by Gorshkov, MK, Moscow, Novyi Khronograf.

[15] Poletaev D., Nasritdinov E., Olimova S. Op. cit.

[16] ‘Starye i Novye Musul’mane Moskvy: Ostorozhnye Otnosheniia’ [The Old and the New Muslims of Moscow: Cautious Relations], 2015, Fergana, January 26. Available from: http://www.fergananews.com/ar ticles/8383

[17] ‘Chto Izvestno o Krupneishem v Istorii Goroda Terakte’ [Factlist on the Biggest Terrorism Act in the History of the City], 2017, RBK, no. № 058 (2555) (0404), St. Petersburg, April 3. Available from: https://www.rbc.ru/news paper/2017/04/04/58e2384a9a7947f3f0173629

[18] ‘Intolerantnost’ i Ksenofobiia’ [Intolerance and Xenophobia], 2016, Levada-Centre, press release, October 11. Available from: http://www.levada.ru/2016/10/11/intolerantnost-i-ksenofobiya/

[19] ‘Uroven’ Ksenofobii v Rossii Dostig Minimuma’ [Xenophobia Rates in Russia Hit a New Low], 2017, Levada-Centre, press release, August 23. Available from: https://www.levada.ru/2017/08/23/uroven-ksenofobii-v-rossii.dostig-minimuma/

[20] Poletaev D., Nasritdinov E., Olimova S. Op. cit.

[21] See, for example: Bolshova, N, 2012, ‘Nemetskie Nekommercheskie Organizatsii na Pomoshch’ Migrantam’ [German Non-Profit Organizations to Help Migrants], Russian International Affairs Council, April 11. Available from: http://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/nemetskie-nekommercheskie-organizatsii-na.pomoshch-migrantam/; ‘Sotsial’nyi Ekskliuziv Migrantov v Mestnykh Soobshchestvakh iz-za Ogranichennogo Dostupa k Sotsial’nym Uslugam i Blagam’ [Social Exclusion of Migrants in Local Communities As a Result of Limited Access to Social Ser vices], 2015, Migration Working Group, US–Russia Social Expertise Exchange. Available from: http://usrussiasocialexpertise.org/sites/default/files/Migration%20Study%20-%20RU.pdf

[22] See, for example: ‘Handbook: Migration Field of Russia’, Russian International Affairs Council. Available from: http://russiancouncil.ru/en/projects/complitedpublishing/migration-directory/

[23] ‘Migratsiia i Pravo. Osnovnye Svedeniia o Programme’ [Migration and Law: Information on the Programme]. Available from: http://refugee.memo.ru/

[24] See: ‘Zaiavlenie Liderov Nepravitel’stvennykh Organizatsii, Rabotaiushchikh v Sfere Migratsii’ [Statement of the Leaders of NGOs in the Sphere of Migration], 2013, Migratsiia 21 Vek, no. 7 (16), January-February, p. 22–25.

[25] The Ural House, a public organization, was founded in 1997. Since then, more than 20 socially important projects in the sphere of migration were implemented under its auspices. The organization includes a legal department as well as medical and education centres, and an Integrated Support Centre for Migrants. Since 2010, it is a regional advisor for the International Organization for Migration in the Sverdlovsk region.

[26] Federation of Migrants of Russia. Available from: http://www.fmr-online.ru/

[27] Assembly of the Peoples of Russia. Available from: http://ассамблеянародов.рф/

[28] See, for example: ‘Spravochnik Moskovskogo Doma Natsional’nostei po Natsional’nym Obshchestvennym Ob»edineniiam g. Moskvy (s Elektronnymi Adresami)’ [Handbook of the Moscow House of Nationalities on Ethnic Cultural Associations in Moscow (with e-mails)]. Available from: http://www.mdn.ru/cntnt/blocksleft/menu_left/ sotrudnishestvo/noogr.html

[29] Milanovic, B, 2011, ‘Global Inequality: From Class to Location, from Proletarians to Migrants’, Policy Research Working Paper, no. WPS 5820, World Bank. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/ handle/10986/3583

[30] The Trade Union of Migrant Workers. Available from: http://www.profmigr.com/

[31] ‘Profsoiuznaia Deiatel’nost’ Kak Nasil’stvennoe Izmenenie Osnov Konstitutsionnogo Stroia’ [Trade Unions’ Activities to Enforce Change in the Foundations of the Constitutional System], 2011, Sova-Centre, July 22. Available from: http://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2011/07/d22173/

[32] ‘Deportatsiia Liderov Koreiskogo Profsoiuza Migrantov’ [Leaders of the Korean Migrant Trade Union Deported], 2007, IUF, December 14. Available from: http://www.iuf.org/cgi-bin/dbman/db.cgi?db=default&uid=default&ID= 4751&view_records=1&ww=1&ru=1

[33] UA Immigration Firm. Available frim: http://migrant.org.ua/

[34] The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations. Available from: https://aflcio.org/

[35] ‘Podenshchiki novogo vremeni’ [Day Workers of the New Time], 2015, Nastoiashchee Vremia. May 27. Available from: https://www.currenttime.tv/a/27040122.html

[36] Interfaith Justice Coalition. Available from: http://www.interfaithjusticesd.org/

[37] Smith, S, 2008, ‘In Search of Decent Work-Migrant Workers’ Rights: A manual for trade unionists’, International Labour Office, Geneva. Available from: https://www.un.am/up/library/Search%20of %20Decent%20Work_eng. pdf

[38] Farm Labor Organizing Committee. Available from: http://www.floc.com

[39] Union Network International. Available from: http://www.uniglobalunion.org/

[40] UNI Europa Professionals / Managers. Available from: http://www.uniglobalunion.org/groups/managers.

professionals/uni-passport

[41] European Migrant Workers Union. Available from: http://www.emwu.org/

[42] South African Domestic Service Allied Workers Union. Available from: http://www.sadsawu.com/