The European

Union, together with its geography, institutions and mechanisms, is

changing. So is the regional integration philosophy per se. The

single vector movement is giving way to a variety of constantly

changing scenarios.

integration is usually compared to a train moving toward a single

destination that is known to all of its passengers. Today, however,

there is a metaphor that more aptly describes European integration:

a hypermarket with numerous shops, cafes, Internet outlets, beauty

parlors, Laundromats, and multiplex cinemas.

There are no more

railway cars where the passengers are reading the same morning

newspaper and looking at the same scene out the window. Nor is

there any sort of set schedule. But most importantly, there is no

destination as such.

Instead, there

are common working hours, parking lots, clean floors and toilets,

and functional escalators. There are also fountains, winter

gardens, and music that plays around the clock. There is plenty of

space here for everybody – civil servants, businessmen, senior

citizens, teenagers, and families with children. A person can

purchase a plasma TV set, a bunch of bananas, a can of coffee or an

investment share acquisition certificate – whatever he

prefers.

The metaphoric

train transformed into a hypermarket so quickly that neither the EU

member states nor their neighbors have appreciated the fact yet.

Thus, the frequent setbacks in EU integration plans, as well as

unprecedented tension in relations with third countries, including

Russia.

GLOBAL

RACE

What is regional

integration and why is it necessary? The European discourse

provides four definitions.

based on the EU’s own experience, primarily in the economic sphere:

integration as the merging of national economies. The three other

definitions are based on theoretical assumptions that belong to

specific political schools of thought.

of European federalism, inspired by centuries-old dreams about the

unity of Europe, see the ultimate goal in the creation of a

superstate. From this perspective, the main hallmark of integration

is the existence of supra-national bodies, to which independent

states delegate a part of their national sovereignty.

so-called communication theory, integration is defined as a

close-knit community based on common values that ultimately lead to

a common identity. A distinguishing feature of integration under

this definition is the existence of closer ties between its

participants than with those outside of the community.

Finally, within

the framework of neo-functionalism, integration is seen as a

collective method of fulfilling practical tasks. National

authorities may delegate executive functions, but not sovereignty.

The public, seeing the practical utility of common institutions,

recognizes and embraces them.

These definitions

differ from one another appreciably, but they have two

shortcomings: they fail to answer the main question, which concerns

the strategic purpose of integration, and they blur the difference

between aims and means.

In accordance

with the federalist concept, which foresees the creation of strong

supra-national bodies, the EU has already passed most of the

distance toward the ultimate goal. However, the ultimate goal –

federation or confederation – is unlikely to be achieved any time

soon. Does this mean that the EU’s current activities are

pointless? Certainly not.

From the

perspective of the communication theory, the EU’s major success

story has been the consolidation of common values. But the EU’s

sense of identity is still extremely ambiguous, as its evolution is

being hampered not only by cultural differences but also by the

absence of a unified political system, as well as the priority of

national over pan-European citizenship.

The intensity of

regional economic relations is an even trickier issue. Trade

between EU member countries only grew at the initial stage of

integration. Since the 1970s, it has been about 60 percent. That is

hardly surprising: further economic rapprochement between the

partners would have disqualified them from international relations,

cutting them off from attractive markets and sources of raw

materials.

The central idea

of the pragmatic economists – i.e., the purpose of integration is

the formation of a single market and a single economy – has failed

the test of time. Although the EU’s internal market has on the

whole been operating since 1993, the “single price” law has been

applied haphazardly at best. Any well-traveled tourist knows that

prices in Sweden are high, moderate in Spain, and low in Bulgaria.

For many types of services, not least financial assets, convergence

of prices is impossible in principle; at best it can be regarded as

a goal for succeeding generations of Europeans.

Bela Balassa’s

theory that says integration passes through four stages of

development – from a free trade zone to a currency union – has now

lost its relevance. According to this logic, the EU has only one

goal left, namely, to expand the euro zone to 27 member countries

without wasting resources on a common defense identity or

scientific and technical policy.

In 2005, the

European Integration Department at the Moscow State Institute of

International Relations (MGIMO), following a series of seminars,

proposed a new definition of regional integration. It bases its

conclusions within the context of globalization, which has two

essential but opposing elements – unifying and divisive.

On the one hand,

globalization intensifies ties between countries and regions, but,

on the other, it divides them into strata, thereby establishing a

rigid hierarchy. Each stratum has its own level of wellbeing,

political, economic and cultural influence, access to resources and

information, the use of advanced technology, and so on.

Under these

conditions, the principal driving force of regional integration is

the striving of the member states to advance to a better stratum

(or otherwise to build a stronger stratum through concerted

efforts) than the one to which they belong (or would belong)

without integration. Not surprisingly, the unification of Europe

started after World War II. That was the time when colonial

empires, which had been calling the shots in the previous era,

began to fall apart, while the United States and the Soviet Union

emerged as the world’s main powers.

Therefore, the

following definition was proposed: regional integration

is a model of conscious and active participation by groups of

countries involved in the globalization-driven stratification of

the world. As mentioned previously, the main goal is

to create the most successful stratum – i.e., strengthening the

group’s positions in those realms of activity that are the most

important for a given stage of globalization. The goal of each

individual country is to ensure the most favorable strategic

environment. Integration makes it possible to maximize the

advantages of globalization and minimize its negative

impact.

So, regional

integration is a model of collective behavior in the context of

global stratification. The creation of supra-national bodies, the

expansion of regional trade, and the introduction of a common

currency or citizenship – all of these are the instruments and

products of regional integration. If tomorrow it is decided that

global leadership will depend upon a country’s ability to grow

square tomatoes, the EU will immediately adopt a detailed plan of

action to that effect.

The most

important element of regional integration is the idea of a common

future of the EU nations. It is important to stress: a common

future, as opposed to a common past. Common histories and similar

cultures, as well as comparable political and economic systems, are

essential but not sufficient conditions for successful integration.

The invisible foundation of integration is constituted by a common

view of its present and future global identity. It is no accident

that the European Constitution opens with the following line:

“Reflecting the will of the citizens and States of Europe to

build a common future, this Constitution establishes the European

Union…” (Article 1.1).

a shared dream about a bright future for oneself, one’s children

and grandchildren. And like any dream, it may or may not come true.

However, a dream, especially one backed up by viable plans, is

better than no dream at all. Therefore, integration is both a dream

and an ongoing project at the same time.

the EU today is indeed reminiscent of a hypermarket. To a well-off

individual, it is a place where he can resolve domestic problems

quickly and without hassles. To a provincial teenager, it is a

model for a better life. It is an exhibition of international

economic achievements that he can easily access – ride a glistening

escalator, listen to a CD of a favorite pop group, buy a cool

T-shirt or discuss the latest cell phone model with a sales

assistant. He can interact in the same venue as the customer who

arrives in an expensive car and uses credit cards to pay for his

purchases.

EU’s greatest attraction.

UNIFORMITY

After the

Maastricht Treaty in 1992 permitted individual countries not to

adopt the euro, experts started talking about multi-speed

integration, and the EU-train metaphor arose once again. But is

integration simply a matter of speed?

question, this author, using data from the World Bank, conducted a

targeted analysis of socio-economic indicators of 34 European

countries, as well as Cyprus and Turkey. The survey did not include

states with a population of less than one million, since such data

are subject to deviation. These countries were classified according

to their level of wealth, as represented by per capita Gross

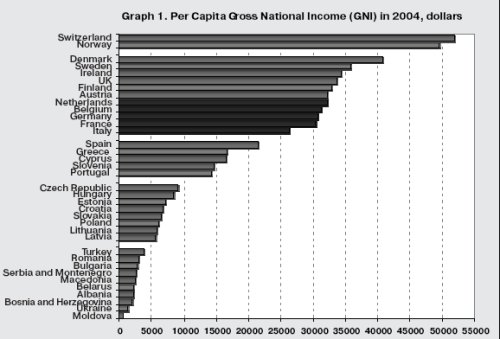

National Income (GNI) in 2004 (Graph 1).

As shown in the

graph, there are five groups of nations, each categorized according

to their relative wealth. The first group, which is made up of the

least prosperous members, comprised 10 countries – six in Southern

Europe (Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, Macedonia,

Albania, and Bosnia and Herzegovina), three in the CIS (Belarus,

Ukraine, and Moldova), and Turkey. The second group includes seven

new EU members from Central Europe (the Czech Republic, Hungary,

Estonia, Slovakia, Poland, Lithuania and Latvia) and Croatia. The

third group is comprised of three backward member countries of the

EU-15 (Spain, Greece, and Portugal) and two successful newcomers

(Cyprus and Slovenia). The fourth group consists of 11 of the

strongest West European EU members. The fifth are the two richest

outsiders – Switzerland and Norway.

capita GNI was calculated for each group (arithmetic mean of these

indicators for each country in a given group. In Group 1, the

average GNI was $2,077; Group 2, $6,913; Group 3, $16,752; Group 4,

$32,767, and in the last group, $50,705). Needless to say, this

method is not absolute and has its limitations. One problem is that

Group 5 is so small, while Group 3 is mainly comprised of

Mediterranean countries. At the same time, this procedure is simple

and provides clear results that are easy to interpret. Its

important advantage is the absence of time frames, which seriously

complicate the identification of trends due to uneven inflation

rates and structural changes. The resultant data provide an instant

picture of Europe’s economic condition in 2004. They point to

changes that occur in society as per capita income grows and, just

like a family picture, provide some idea about the age

distribution.

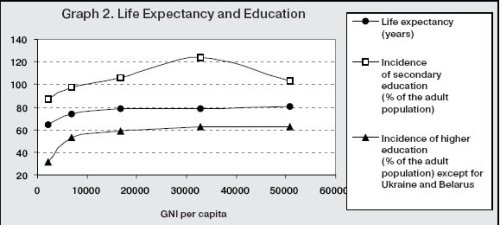

expectancy, the difference between Group 1 and Group 5 is 16 years

– 65 and 81 years, respectively (Graph 2). Remarkably, the first

step – transition from Group 1 to Group 2 – accounts for one-half

of the total increase, i.e., eight years. The next step adds five

more years. So in Group 3, life expectancy actually approaches

Europe’s (and the world’s) highest level.

In the poorest

countries (except Bulgaria), secondary education was not available

to all adults. However, that problem was effectively resolved

already in Group 2, while in Group 4, one person in five has a

second secondary education. The incidence of higher education

largely depends on the national model. The highest proportion of

people with university degrees is in the Scandinavian countries –

Norway, Sweden and Finland (80-87 percent of the adult population).

In highly developed states of Western Europe, this indicator is on

average 62 percent (including in Austria 49 percent and in Germany

50 percent). In the poorest countries of Southern Europe and

Turkey, only 31 percent of adults have a higher education, while in

the Central European countries the level is 53 percent. As in the

case of life expectancy, the most substantial difference is between

Groups 1 and 2.

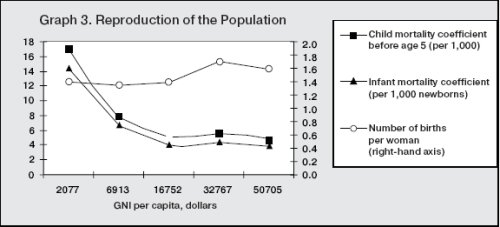

pattern is observed in the instance of infant mortality (Graph 3).

In Group 3, with a per capita income of at least $14,000, not more

than nine out of 1,000 newborns die before age five. In Group 1,

the coefficient is almost double that. The situation is especially

bad in Turkey, where 60 out of 1,000 children die before age five.

In Poland, the coefficient is 15, in Germany 9, in Finland 7, and

in Switzerland 10.

births per woman (fertility coefficient) provides some interesting

statistics. There are two different models in Group 1. The first

model is characteristic of former socialist states – Bulgaria,

Romania, Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus – where the average number of

births per woman varies between 1.2 and 1.4. In Turkey and Albania

(where Muslim traditions are strong), the coefficient is 2.2 (in

Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro, the figure is 1.7). On the other

hand, Groups 2 and 3 are extremely homogeneous with 1.2 to 1.4

births per woman.

A marked increase

in the birth coefficient occurs in Group 4. That refutes the common

belief that there is an inverse proportion between income growth

and the birth rate. In the Netherlands and Finland, birth rates are

higher than in Spain and Greece. It is possible that higher birth

rates in more prosperous states are due to an inflow of immigrants

from the Third World, as well as the social model (especially in

Scandinavia), and family support programs. Whatever the case may

be, in rich European countries (except Germany and Italy) the

population is aging more slowly than in the relatively poor

countries.

Modernization and new technology.

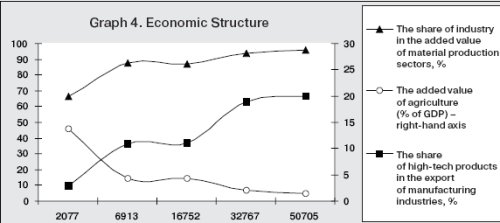

In the less developed countries, agriculture generates between 11

and 21 percent of GDP, as compared to 1-3 percent in the most

developed countries (Graph 4). But can such a low share of the

agrarian sector in West European GDP be attributed to its

large-scale services industry? To exclude this factor, the share of

industry in material production was calculated for each country.

The results show convincingly that economic development goes hand

in hand with steady industrialization. Thus, in Bulgaria, industry

accounts for 74 percent of material production, as compared to 87

percent and 92 percent in Portugal and France,

respectively.

The substantial

gap reflects a global move toward specialization. High-tech

products in the total export of the manufacturing industry are 3

percent in Group 1, 11 percent in Groups 2 and 3, and 19 percent in

Group 4. It is noteworthy that the high-tech export curve is a

mirror-like reflection of the share of agriculture in

GDP.

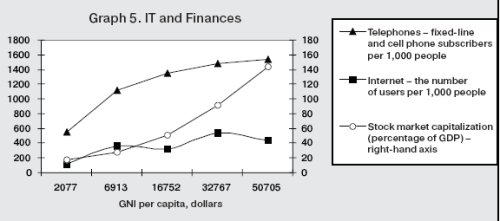

Internet penetration rates in the EU’s leading states are three to

four times higher than in the weaker states (Graph 5). As per

capita income grows, the number of fixed line telephone networks

and cell phone subscribers increases more evenly than, for example,

does life expectancy or the spread of higher education. Although

even here, the rates appear to be slowing.

The unusual form

of the graphs reflecting the process of industrialization (Graph 4)

and Internet penetration (Graph 5) – i.e., the equality of Group 2

and Group 3 indicators – may have the following explanation. Group

3 is comprised of states that are the largest agricultural

producers in the Mediterranean. Agriculture there has deep

historical and cultural roots. By contrast, Group 2 includes former

socialist countries, which (during the COMECON period) pursued an

active export-oriented industrialization policy. For example, in

Hungary, high-tech products account for 29 percent of industrial

exports: it ranks second in Europe by this indicator, together with

Germany.

markets present an entirely different picture. Unlike the majority

of the aforementioned indicators, stock market capitalization

increases not along a horizontal parabola but an exponential curve

(upward). The value of stocks and bonds circulating in the country

in relation to GDP increases 11 percentage points from Group 1 to

Group 2, 23 points from Group 2 to Group 3, 40 points from Group 3

to Group 4, and 53 points from Group 4 to Group 5.

Cluster strategies. Analysis

shows that different groups of countries in the EU are moving

toward integration not only at a different pace. They each have

their own priorities.

Romania, and aspiring states have yet to complete the process of

industrialization, modernize education and healthcare systems, and

build up their infrastructures. They need to restructure the

agricultural sector, diversify and strengthen its specialization

techniques, and ultimately enhance its profitability. Prospects for

industrial growth also require a clear prioritization of goals, as

well as foreign investment and technology. In the next 10 to 15

years, these countries will be unable to appreciably upgrade their

industry and increase the export of high-tech

products.

It is also

critical for the Central European states to develop their

healthcare and higher education systems. With a balanced economic

policy, they have a good chance of catching up with the EU leaders

in terms of life expectancy and child mortality rates. But

according to EC forecasts, before 2050, the population of these

central states will continue to age. Poland, the Czech Republic,

Hungary, Slovakia and the Baltic States have effectively completed

their industrialization programs, but they will work many more

years to modernize their industry. However, their ability to

implement large-scale, investment-intensive R&D programs will

remain limited in the foreseeable future.

In Spain,

Portugal, Greece, Slovenia, and Cyprus, the categories of life

expectancy, infant mortality, and secondary and higher education

effectively correspond to the level of the EU’s leading nations.

The priority here is to complete the retooling of industry and

sharply increase the share of cutting-edge, research-intensive

production. Judging by Ireland’s experience, that goal is quite

feasible. Spain, Portugal and Slovenia, for example, have set the

stage for a new breakthrough in the pursuit of national R&D

programs, as well as modern information society.

developed EU countries are destined to play a special mission here.

Due to their economic and political weight, they set priorities and

define the type and pace of integration. They also bear the utmost

responsibility for the Union’s future. The most important goal is

to retain the positions that have already been attained:

maintaining the present social standards, ensuring stable (albeit

not very high) economic growth rates, and being globally

competitive. Strategic considerations are connected with the

development of the “knowledge society”: improving the quality of

education, developing high technology, upgrading IT systems, and

enhancing the liquidity of financial markets.

Therefore,

stratification occurs not only worldwide, but also within the EU as

a result of global competition and the growing differentiation of

the EU countries. In the European “hypermarket,” some stock up on

economy-class detergent, others rejoice at the sight of 50

different brands of ice cream, while still others pick and choose

from a variety of sea products. One should not, however, get the

impression that the first group experiences great difficulties

whereas the third group has an easy life. It is important to

understand that a hypermarket is not a train that will deliver its

passengers to their destination as soon as possible. A hypermarket

is a product of globalization. It offers buyers goods from all over

the world, goods that meet international standards of quality.

Unlike the train, where the choice is made only once, the burden of

freedom in the hypermarket is constant. Everyone has to make a

decision every minute as to how to spend his money and

time.

THE POWER OF

EMOTION

peace and the end of the Cold War have affected European policy

just as the great diversity of goods has affected consumer

behavior. Today, when a person buys a leather or cashmere jacket,

he is less concerned about keeping warm than creating his own

identity. By buying a certain product, he makes a policy statement,

declaring his affiliation with a certain social group whose values

he shares. Whereas in the past, the main issue on the political

agenda was the issue of war (real or imaginary), today the problem

of identity and the related feelings and emotions has taken center

stage.

At the beginning

of this century, the extremely complex goal of building a common

European identity became one of primary importance.

heterogeneous. A huge influx of immigrants has changed the cultural

and religious landscape in many EU countries. The admission of new

members not only increased the number of EU official languages but

also greatly deepened economic inequality. In 1950, when the

European Coal and Steel Community Treaty was signed, GDP per capita

in Belgium (at the current exchange rate) was 130 percent higher

than in Italy. Today, the gap between the richest and the poorest

EU countries (Denmark and Bulgaria) has reached 1,400 percent.

Incidentally, Graph 1 shows that the EEC founding members are still

a remarkably close-knit group in terms of their levels of

prosperity.

Second, following the breakup of the

Soviet bloc, the EU no longer had an ideological adversary, whose

existence helped European nations – so different and not always

amenable toward one another – to share something of a common

identity. It has to be said that the Soviet Union was an ideal

opponent for Western Europe, and today it cannot be replaced either

by the United States or by other global forces or

regions.

complex that the majority of the population cannot understand them.

But broad public support is critical for integration and the

evolution of a common European identity.

The sharp

alteration in the global system of orientations has produced two

conflicting sentiments among the West Europeans. On the one hand,

there is a sense of pride, which oftentimes reaches the point of

conceit, with the market system and its historical vindication. On

the other, there is a sense of confusion and anxiety about the

future. It is important to understand that it is psychologically

more difficult for Western Europe to adapt to a new stage of

globalization than it is for any other part of the world. European

civilization is based on sheer rationalism, aspiration for optimal

calculations of action, and a sense of morality. Meanwhile,

globalization is destroying stereotypes, requiring unconventional

solutions and demanding creativity. The majority of average

Europeans feel extremely uncomfortable about this new

scenario.

consolidate the sense of security and form a positive European

identity compelled the EU to prioritize values. In 1993, Copenhagen

Criteria – the rules that define whether a country is eligible to

join the EU – were laid down. These requirements include democracy,

the rule of law, human rights and respect for, and protection of,

minorities, and the existence of a functioning market economy. That

system of values provided yet another important means of global

stratification, namely the right to require others to comply with

these norms (as defined by Brussels).

consolidate an all-European identity had a substantial impact on

daily practices, and not all of them positive. General statements

by EU leaders and documents of EU executive bodies are looking

increasingly bland. Open debate, which brought glory to European

culture, is giving way to mere political rhetoric. The goal of EU

functionaries is to ensure that the average people do not have

negative emotions, and they are quite skillful at

that.

“Consumer tuning”

of EU programs and institutions has become a separate genre. Thus,

the campaign in favor of a currency union was built on the

assumption that people will save up on exchange costs and that new

jobs will be created in Europe. The former belief was a proven

truth, while the latter proved to be a bit of an exaggeration;

however, neither goal has really anything to do with the real

purposes of the project. The main goal of integration is to ensure

Europe new global advantages and accelerate economic modernization

by invigorating market forces. But that is not enough to convince

the people of the importance of the project. Every time the

European Central Bank raises the refinancing rate, it cites the

threat of rising prices. In reality, however, the real reason is

either the declining rate of the euro or a change of interest rates

in the United States. But the public must believe that the ECB

safeguards its interests.

point is the EU’s financial policy in 2007 through 2013. Its top

priority is presumably sustainable growth, in accordance with which

there are two budgetary lines: competition in the interest of

growth and employment and consolidation in the interest of growth

and employment.

A mere nine

percent of the EU budget has been earmarked for the first category,

including scientific and technical policy and innovation,

education, trans-European networks, social policy and a functioning

market economy. The second line, aimed at providing assistance to

backward regions, will consume a whopping 36 percent of the budget.

Thus the EU’s traditional regional policy has ended up under the

respectable slogan of sustainable growth. The second priority is

far more disingenuous: “preservation and management of natural

resources” is used as a cover for agricultural policy, which has

long been out of tune with the times, and is also an unbearable

burden for the EU (43 percent of the entire budget).

source of intense passion is the EU’s eastward expansion. Many West

Europeans were skeptical about it: they were concerned – and for

good reason, too – about the redistribution of budgetary resources

in favor of poorer regions. The Central Europeans were inspired by

the prospects of joining the EU. They had high hopes, not least for

better living standards. Membership in the club of prosperous

nations was also a matter of prestige, a source of national pride,

and a means of overcoming the ‘little brother’ inferiority

complex.

At the same time,

the philosophy of the Copenhagen Criteria and the condemnation of

everything that had existed in the Soviet bloc contributed to the

inferiority complex. Aspiring countries, as represented by their

leaders and elites, worked hard to prove to the West that they had

always been 100 percent Europeans. Some countries were resentful of

their new partners. Problems dating back to World War II and the

postwar world order quickly came to the fore.

Many people in

Central Europe proved unable to accept their own history. That fed

the illusion about ‘the good old days.’ Since many of those

countries appeared on the map after World War I, their nostalgia

focused on the period in between the two wars, one full of

nationalism and brutality. Those considerations were used as a

sedative for the subsequent resentment. For example, The Estonia

Passport, an official publication, asserted that more than 60

countries boycotted the 1980 Olympic Regatta in Tallinn as a token

of solidarity with the occupation of the Estonian

Republic.

Whatever the

case, Brussels is making a serious mistake by withdrawing the

history of the socialist era from public discourse. Serious

analysis of this subject is, as a rule, replaced by an ideological

caricature. Essentially, the life of two or three generations of

Czechs, Poles and Hungarians is surrounded by a conspiracy of

silence and sheer condemnation. But without respect for one’s

predecessors, or the history of one’s country, a nation cannot

really have a sense of dignity or self-respect, which enables it to

make vitally important decisions.

understandable why the EU avoids this issue. Debate about the

Soviet past would blur its present values and identity. Brussels is

also reluctant to officially state its position, seeking to avoid

public discord and yet another adjustment of relations with the

United States, Russia and the CIS.

But the danger of

this practice is not only that Europe is jeopardizing its most

valuable assets – democracy and common sense. It could eventually

give the Central European countries a sense of inferiority with

respect to other EU members, as a result of which they will be

unable to embrace its common goals and assume responsibility for

its future. This author has often asked her colleagues from Central

Europe about the type of contribution they would be ready to make

to attain the EU’s common goals. Invariably, this question caused

incomprehension, surprise or confusion.

Lack of

initiative, the reluctance to forge one’s future with one’s own

hands, and the inability to creatively appraise the ongoing

developments are the greatest sins of the globalization era. Its

principal assets are the assertion of the finest global standards,

innovation, a multidimensional view of reality, and tolerance

toward others. That applies both to the EU as a whole, and to its

individual member states.

The new model of

European integration responds to the needs of globalization better

than the previous model, but it is far more difficult to manage and

control it.