For citation, please use:

Chesnakov, A.A. and Parenkov, D.A., 2024. Bristling States in Search of an Antidote to Foreign Interference. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(3), pp. 71–86. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-3-71-86

Rapid technological, social, and cultural changes in the last two decades have dramatically complicated international interactions. One of their consequences was the growth and diversification of external influence in spheres that had been considered sovereign, which caused states’ hurried institutional responses to this threat. A marked transformation of the international environment and the arrival of new actors are mainly responsible.

The Shift

Technological change has made political phenomena increasingly extraterritorial. Advancements in communications and logistics, especially digital advancements, have blurred the traditional boundaries of political action. Previously, foreign threats were clearly associated with actions by states or their direct proxies. The erosion of cultural, normative, informational, technological, and resource boundaries makes the source of a threat difficult to identify. National governments face a real threat of losing their monopoly on decision-making.

New types of political activity have emerged in traditionally state-controlled spheres, and a number of technological and communicative processes have acquired political significance but remain beyond state control. IT giants claim the right to the autonomous use of digital force. Transnational digital platforms control targeted-advertising algorithms and can convert their users into a special kind of social capital. Communication mechanisms have entered into computer games and entertainment streams. Politicians as opinion leaders compete with influencers for audiences. Kanye West’s political manifestos and election campaigning on Twitch have heralded the erosion of familiar institutional frameworks. There has emerged a vast gray zone in which political action is possible outside the existing rules.

Transnational corporations, international organizations and programs, cross-border social movements, and even individuals now potentially generate political risks. A digital political action or position needs not rely solely on supporters physically within the national borders. In effect, there has emerged an unlimited “online constituency,” in which one can compete for supporters regardless of their citizenship. For example, ‘likes’ from Pakistan and Puerto Rico, regarding solutions to environmental issues, can just as easily influence Scandinavian public opinion.

Interstate and nongovernmental organizations have also played a role. Driven by expansive interpretations of their mandates and missions, and responding to growing doubts about the role and effectiveness of international organizations, some increasingly dismiss state borders and undertake contentious actions.

The 2020 amendments to Russia’s Constitution established its priority over the decisions of international organizations and courts, and Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept (2023) mandated “countering the use of human rights issues as a tool for external pressure, interference in the internal affairs of states and destructive influence on the activities of international organizations.”

The social situation has transformed qualitatively. Face-to-face communication and common everyday practices are no longer needed for the formation of group identity. Social identities have transcended state borders and can be ‘remotely verified’ through inclusion in a common, transnational communicative space.

Identities, based solely on virtual experience, have become widespread. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, sociologists noted the spontaneous unification of people—even those who had never been to New York—around the idea that “we are all New Yorkers.” The formulas “all of us…,” “I/we,” “me too,” etc. have been repeatedly used to create subjective and situational politically-colored identities.

A number of identities (gender, race, etc.) have received external backing from foreign and international actors. Dual political loyalty—to nation-states and to transnational groups—has become common for such identities.

States perceive the transnationalization of group identities as a potential threat. The political priorities of some groups obviously presage conflict with national (civil) identity. Hardline solutions to the problem, through bans or cancelation of some group identities, tend to complicate things, as they trigger identities’ compensatory function to provide solidarity and belonging in the context of social alienation (Bilgrami, 2006).

When some social identity is perceived as deviant or exposed to pressure, its bearers can seek support outside the state. In the past, retention of civic identity, with its accompanying rights and freedoms, typically took precedence over political emancipation. Now, connection with a large supranational group, and the support expected from it, may ease such fears, facilitating defection to the state’s opponents.

Another source of change is the unresolved or poorly resolved problems caused by the geopolitical crises of the 1990s. A short-lived delusion of inevitable openness was fueled by the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the end of the Cold War, and inflated expectations of rapprochement between former adversaries within the context of globalization. Even open interference in domestic politics was often perceived as a necessary part of fitting a country into the new world order. For example, in 1992, the U.S.-government-supported National Democratic Institute held a series of working meetings on the development of Russia’s electoral and party system with the authors of the relevant draft legislation (McFaul and Mendelson, 2000).

However, with a growing awareness of the realities of the new world order (including the limited opportunities for integration into the global Western project), Russia, China, and other non-Western powers reassessed their places in the world and the limits of their own sovereignty. They recognized not only the opportunities but also the threats posed by interaction with their foreign counterparts.

The ‘democracy-authoritarianism’ dichotomy produced skepticism of actual or perceived non-democracies.

It was in the 1990s that the topic of interference gained particular prominence in academic research. “Foreign political engagement” was defined as “the calculated action of a state, a group of states, an international organization or some other international actor(s) to influence the political system of another state (including its structure of authority, its domestic policies and its political leaders) against its will by using various means of coercion (forcible or non-forcible) in pursuit of particular political objectives” (Geldenhuys, 1998, p. 6). Foreign interference is “targeted at the authority structures of the government with the aim of affecting the balance of power between the government and opposition forces” (Regan, 1998, p. 756).

Stage One: perception

Initially, interference was the domain of the powerful and usually manifested itself as overt military interventions and coups: “almost everything scholars know about the subject… is based on… powerful states meddling in weak ones” (Wohlforth, 2020). Over time, however, the phenomenon took on more pervasive and complex forms.

Major powers’ perception of the threat posed by external interference prompted a more meaningful analysis of the problem. Previously, they were primarily interested in legitimizing their own actions (hence the concept of ‘humanitarian interventions’), while the targets of interference were struggling for political survival, lacked the necessary intellectual resources, and were excluded from the discourse. This changed with the emergence of new actors and new roles.

The Soviet Union’s support for foreign Communist parties was dictated more by the ruling party’s ideology than by the state’s interests. The 7th Congress of the Communist International, held in 1935, accordingly emphasized the need for “proceeding from the specific conditions and peculiarities of each country and avoiding, as a rule, direct interference in the internal organizational affairs of Communist parties” (Titarenko et al., 2007, p. 669). In 1943, Stalin explained that the Comintern was being dissolved partly because “the Communist Parties belonging to the [Comintern] are falsely accused of being alleged agents of a foreign state, and this hinders their work among the broad masses. With the dissolution of the [Comintern] this trump card is knocked out of the hands of the enemies. The step taken will undoubtedly strengthen the Communist parties as national labor parties and at the same time strengthen the internationalism of the masses, the base of which is the Soviet Union” (Adibekov, 2004, p. 812).

In the case of the United States, as Igor Istomin writes, “although the Soviet Union represented the most significant strategic target for the United States, it was subject to relatively modest subversion in contrast to that against less capable states” (Istomin, 2022). Liberal democracies saw intervention and interference as suitable tools for influencing “weak states of a non-liberal character” (Doyle, 1983).

Since the end of the Cold War, major powers have used interference against each other on a new scale and in new ways. In many countries, the intelligence community is actively involved in conceptualizing foreign interference and in doing so draws a clear line between it and espionage. Whereas espionage is one of the many means of obtaining information and thus an advantage over a rival, intervention aims to “influence, disrupt or subvert target’s national interests.” Such a distinction is proposed in the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s report entitled New Zealand’s Security Threat Environment 2023 (NZSIS, 2023).

CIA Director William Burns has aptly remarked that “espionage has been and will remain an integral part of statecraft” (Burns, 2024). Interference, on the other hand, is seen as something that is outside the established rules of the game. Even in the rare cases where espionage is categorized as interference, its routine nature is emphasized and contrasted to more novel forms of influence. For example, the French parliamentary delegation on intelligence described espionage as a “classic” form of interference (Rapport Relatif, 2023).

The targets of interference have not upheld these semantic distinctions. In Russia, rethinking the threat of interference began in the 2000s, prompted by disappointment with integration into the West, by increasingly obvious attempts at external influence on Russian domestic politics, and by a series of “color revolutions” and coups near Russia’s borders. The latter began with the Rose Revolution in Georgia and Orange Revolution in Ukraine. This prompted openly hardline official rhetoric and debate about national sovereignty within growing globalization.

In 2006, Russia enacted its first legislation regulating foreign-funded NGOs. In Western publications, this innovation is often regarded as the beginning of restrictions, around the world, on foreign involvement in NGOs. However, it was actually just one part of a global trend. For example, a similar measure was introduced in India in 2006 and passed in 2010, completely banning foreign funding of political activities (FCRA, 2010).

The issue was brought to a head by the Arab Spring, which brought uprisings, regime change, and civil war to almost all of North Africa. Interference drew growing attention from both policymakers and experts. However, in the perception of both policymakers and experts, the political goals of interference are often blurred by the accompanying social and informational processes.

In Russia, mass protests in December 2011-February 2012, fueled by heavy foreign funding, had a considerable impact on views of the Arab Spring. The authorities opted for a hardline approach to managing interference risks. On 13 July 2012, the State Duma amended the law “On Non-Profit Organizations,” introducing the status of ‘foreign agent’ for Russian NGOs engaged in political activities in Russia and receiving foreign funding. Later, in 2015, the concept of ‘undesirable organization’ was added to the legislation.

Discussions of foreign interference received a new impetus with the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, to which the topic was central. Attention to the issue has since become far more systematic around the world, including in official doctrines and legislation. Administrative and criminal legislation establishes the corpus delicti of crimes related to foreign interference, and specialized institutions are created to counter interference attempts. By 2018, more than 50 states had restricted or entirely banned foreign funding of political activities (Mayer, 2018), not to mention other counter-interference mechanisms.

The topic’s discussion has been complicated by its politicization within the U.S., and it is torn between the extremes of justification versus harsh restrictive measures.

It is also burdened and obfuscated by obsolete terminology. For instance, the term ‘foreign agent’—whether used negatively to mean association with foreign intelligence services, or neutrally to mean action in the interest of the principal—refers to the practices of previous eras. In fact, the actors now defined by this concept have vague political loyalties that vary depending on the domestic environment and external influences. Not all act consciously. However, all bear hybrid worldviews and act as channels for the import of values. The authorities see them as dangerous annoyances and proponents of foreign interests. Even if these interests do not necessarily contradict the interests of the rest of society, they are still implicitly hostile as products of another political system, another “symbolic universe” (Berger and Luckmann, 1990).

Stage Two: reaction

The threats stemming from technological, social, and geopolitical changes and regulatory imbalances could not be left unanswered. Political systems had to equalize internal pressure with that of the external environment. Initial efforts at self-defense were naturally chaotic.

An in-depth analysis of interference countermeasures is complicated by the asynchronous nature of states’ adaptation to the threat. Each state has its own degree of immersion in the new technological order and its own history of encounters with interference.

For some countries, certain aspects of interference simply do not exist. There can be no interference in digital electoral infrastructure if there is no such infrastructure. For most countries, interference in electoral infrastructure can be nothing more than old-fashioned physical seizure of a polling station or an entire constituency.

Some countries’ histories have made them very sensitive to the problem of interference, while others have not yet developed sufficient mechanisms for recognizing it. Russia’s heightened alertness was produced by the collapse of the USSR and then of illusions regarding openness’s unalloyed goodness.

States’ institutions for countering foreign interference also vary. Some focus on protecting electoral processes and on limiting foreign support for the opposition, while others focus on protecting education and research and on regulating digital platforms. Actions are taken both regarding infrastructure (e.g., the development of technology to protect critical infrastructure such as communications and electronic electoral systems) and regarding individuals and organizations (e.g., restricting or prohibiting foreign influence on the political system via specific actors).

A number of countries complement institutional restrictions with social and political pressure on those political actors that seek support abroad or directly act in the interests of foreign states. Foreign-supported political and sub-political activities are stigmatized, and their participants become “outcasts,” often pushed to the periphery of the political arena or out of it altogether.

The institutionalization and legitimization of political stigmatization is done in three ways. First, specific states and their supporters or representatives are labeled as threats in legislation and other official documents (for example, the West’s reference to a ‘Chinese threat’ in academia). Second, demonstrative procedures convey some form of condemnation (for example, the French National Assembly’s hearings on foreign political, economic, and financial interference). Third, specialized labeling directly imposes stigmatization (for example, Russia’s register of foreign agents, the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), and the UK’s Foreign Influence Registration Scheme (FIRS)). The EU is implementing a similar mechanism within the Defense of Democracy package, and France and Canada are also discussing the urgent need for registers of foreign influence.

Foreign interference is presented as a danger common to all countries, stemming from attempts by individual states to blur the boundaries of national sovereignty and interfere in others’ internal affairs. In contrast, the U.S. and its allies reject the universalization of the threat, adhering to interference narratives based on different principles. Western official discourse rarely connects foreign interference to sovereignty, and instead narrows the concept to “interference in democratic processes” or (even more specifically) to “interference in elections.”

Executive Order 13848, “Imposing Certain Sanctions in the Event of Foreign Interference in a United States Election” (Executive Order, 2018), emphasizes that “foreign powers have historically sought to exploit America’s free and open political system.” The U.S. National Security Strategy similarly states that “America will not tolerate foreign interference in our elections” and “will act decisively to defend and deter disruptions to our democratic processes” (The White House, 2022). Thus, foreign interference is understood primarily as an attempt to influence elections by affecting electoral infrastructure and via information campaigns for or against specific candidates/parties.

This avoidance of a more general conceptualization is explicable given the West’s flexible approach to interpreting threats and justifying protective measures. The Western strategic narrative of interference is built around three key elements: drawing a normative distinction between interference against democracies versus non-democracies; narrowing the definition of interference with a focus on specific risks; and attributing threats to specific countries or groups of countries.

The latter is also observed in Russia, where interference is discursively associated with the Western countries, but this is limited at the official/legislative level. In the U.S., the linkage of the threat of interference to specific actors is a well-established tradition. As early as 1918, the Senate created “a subcommittee to investigate German and Bolshevik propaganda” (CRS Report, 2020), and in 1938 the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) was passed amid concerns over Nazi Germany’s propaganda activities. This tradition continues with the October 2022 U.S. National Security Strategy, which blames foreign interference on specific countries: China, Russia, and Iran (The White House, 2022).

Stage Three: conceptualization

Over the decades, states have moved from recognizing the problem of interference to attempting a systemic response. The initial reaction was similar to piloerection in animals, as states bristled against the threat. Evolutionarily, this reflex demonstrates a sensitivity to external stimuli and a readiness to retaliate and is associated with maintaining or challenging the existing hierarchy (Muller and Mitani, 2005). Similarly, states demonstrate a willingness to assert sovereignty in various spheres and use the defenses available to them. The reflex inevitably outstrips rational comprehension of the situation, and its conceptualization remains sketchy.

Once, states generally acted straightforwardly: if there was a sufficient imbalance of capabilities (or perceptions of such an imbalance), the stronger actors used diplomatic, economic, and even military interventions. However, advancements in information and communication technology have granted states a wider range of indirect instruments of influence, and a greater ability to vary the degree of pressure. Some of these processes were conceptualized as ‘soft power,’ which could not have emerged without information flows strong enough to influence foreign audiences. However, categorizing the instruments of external influence solely by their hardness is clearly insufficient.

Their conceptualization has also seen the emergence of certain ambiguities. The first attempts resulted in the confusion of ‘intervention’ with ‘interference’ (Bartenev, 2018), while some authors assert the concept’s essential indeterminacy (Istomin, 2023). Academics and practitioners now offer contradictory distinctions between ‘interference’ and ‘influence’ and various typologies of such activities. State actors have joined these processes. For example, research carried out on a grant from the Australian Department of Defense has produced a model for analyzing interference with regard to the most vulnerable elements of political systems: institutions, infrastructure, industry, individuals, and ideas (Henschke et al., 2020).

The existing approaches’ key problem is their attempt to exhaustively explain various related phenomena through a single concept. In fact, interference does not supplant but rather supplements previous practices, which are altered and obtain greater flexibility and more opportunities for use.

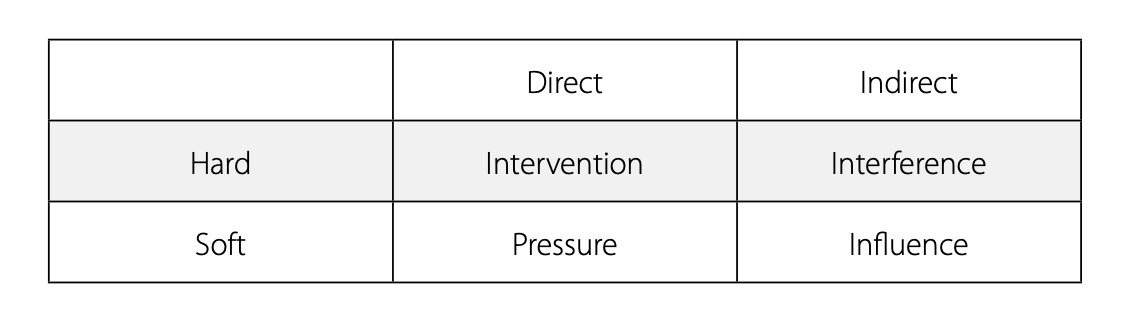

An action’s most important characteristics are the degree to which it is direct (or indirect) and hard (or soft). Intertwining, these characteristics make up the following matrix:

Direct actions include intervention or overt pressure.

Intervention is inherently hard but is not limited to military incursion, instead including all crossings of sovereign borders: informational, electoral, cultural, educational and other interventions. Cultural intervention, for example, could include support for cultural projects in a foreign country aimed at undermining the government.

Pressure entails the use of economic, diplomatic, political, and other instruments to change a state’s behavior. For example, unilateral economic sanctions.

Indirect actions can be termed interference if hard and influence if soft.

Influence does not necessarily entail negative effects on the target of influence. It can be exercised openly and is generally regarded as legitimate practice in international relations.

Interference, on the other hand, is usually covert and always aimed at harming the opponent.

The difference between influence and interference may also be seen in the way they are addressed. In its June 2023 report, the French Commission of Inquiry on Foreign Interference stated: “Influence can most often be tolerated and is tolerated, which is not the case with interference” (Rapport d’enquête n°1311, 2023).

All foreign activities fit into this typology. In the electoral sphere, which is most sensitive to external influence, all four types of foreign activities are clearly visible. Influence manifests itself in assessments by foreign actors of electoral procedures and campaigns. Pressure is enforced, for example, through sanctions on elections officials, calls for changes in legislation, etc. Interference is more covert: from non-public support for the opposition to targeted long-term “nurturing” of future candidates through leadership training programs. Finally, direct attacks on electronic election infrastructure, or the dissemination of misinformation (e.g., falsified opinion polls), are electoral interventions. The list of tools to affect elections is far longer, but all of them fall into one of these four categories.

Balancing

Interference is commonplace today and will likely become only more so, especially as it has become possible in “endoscopic” form. Channels and instruments are hidden, and external interests can exert themselves from within the sovereign political space.

The escalation of tensions between Russia and the West, between China and the West, and generally around the world, only adds to the importance of the matter.

As countries approach future political cycles, they observe interference in various disguises and hope that the most destructive types are not directed against them. Their first reactions seek to eliminate vulnerabilities. Most major powers have begun developing protective mechanisms, but this is just the beginning.

The British National Security Act and the Hungarian Act on the Protection of National Sovereignty, both adopted in 2023, emphasize measures to counter foreign interference in elections. In the United States, various initiatives are constantly emerging at both the federal and state levels. For example, in April 2024, Senator Bill Hagerty, along with other senators, introduced the Preventing Foreign Interference in American Elections Act. Before the 2024 elections, Taiwanese officials offered a cash reward for evidence of foreign interference. Even before the Russian presidential campaign began, it was clear that attempts to meddle would be part of the overall drama. Attempted interference will also surely enjoy special attention in the upcoming U.S. and British elections.

Special apprehension, regarding the security of the processes of power-formation, is understandable. However, an excessive emphasis on elections may be counterproductive. Firstly, claims of foreign interference are weaponized in internal political battles, hindering objective analysis. Secondly, less obvious (but no less significant) cultural, educational, and economic processes (strategic infrastructure, etc.) should not be ignored.

An over-simplified or reductive approach to matters can lead to exaggerated reactions or careless neglect. Without meaningful discussion, the analysis of interference and related phenomena may well be displaced by moral evaluations that are far-removed from reality. Further technological development, including the spread of artificial intelligence, will make the topic more controversial. States will long remain in the position of Achilles, patching up legal loopholes to keep pace with the technology of their competitors.

In the long run, the conceptualization of interference is likely to become increasingly diverse, followed by tougher rhetoric and firmer domestic countermeasures. The sooner the countries realize that they are dealing with a complex system of interrelated phenomena, the more effective and less painful the adaptation process will be. Challenges and institutional responses must be balanced. Given the speed of the ongoing processes, equilibrium will probably not be attainable for several decades.

Influence, pressure, interference and interventions require different responses. How quickly they are identified will determine the degree of sovereignty held by states in the new system of international relations.

Adibekov, G. (ed.), 2004. Politbyuro TSK RKP(b)‒VKP(b) i Komintern. 1919–1943 gg. Dokumenty [Politburo of the Central Committee of the RKP(b)‒VKP(b) and the Comintern. 1919–1943. Documents]. Moscow: ROSSPEN.

Bartenev, V., 2018. Vmeshatelstvo vo vnutrennie dela: spor o definitsii [Interference in Internal Affairs: Questioning Definitions]. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya 25: Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya i mirovaya politika, 10(4), pp. 79-108.

Berger, P.L. and Luckmann, T., 1990. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor Books.

Bilgrami, A., 2006. Notes Toward the Definition of Identity. Daedalus, 135(4), pp. 5-14.

Burns, W.J., 2024. Spycraft and Statecraft. Foreign Affairs, 30 January. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/cia-spycraft-and-statecraft-william-burns [Accessed 10 April 2024].

CRS Report, 2020. Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA): Background and Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service, 30 June. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46435 [Accessed 10 April 2024].

Doyle, M.W., 1983. Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs, Part 2. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 12(4), pp. 323-353.

Executive Order, 2018. Executive Order 13848. Imposing Certain Sanctions in the Event of Foreign Interference in a United States Election. U.S. Government Publishing Office, 12 September. Available at: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-13848-imposing-certain-sanctions-the-event-foreign-interference-united [Accessed 16 May 2024].

FCRA, 2010. Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act. fcraonline.nic.in, 27 September. Available at: https://fcraonline.nic.in/home/PDF_Doc/FC-RegulationAct-2010-C.pdf [Accessed 16 May 2024].

Foreign Policy Concept, 2023. The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation (Approved by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 229, March 31, 2023). Kremlin.ru, 31 March. Available at: http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/files/ru/udpjZePcMAycLXOGGAgmVHQDIoFCN2Ae.pdf [Accessed 10 April 2024].

Geldenhuys, D., 1998. Foreign Political Engagement. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Henschke, A., Sussex, M., and O’Connor, C., 2020. Countering Foreign Interference: Election Integrity Lessons for Liberal Democracies. Journal of Cyber Policy, 5(2), pp. 180-198.

Istomin, I.A., 2022. Military Deterrence vs Foreign Interference? Record of the Cold War. MGIMO Review of International Relations, 16(1), pp. 106-129.

Istomin, I.A., 2023. Inostrannoe vmeshatelstvo vo vnutrennie dela: problematizatsiya sushchnostno neopredelimogo kontsepta [Foreign Interference in Internal Affairs: Deconstruction of an Essentially Indeterminate Concept]. Polis. Politicheskie issledovaniya, 2, pp. 120-137.

Mayer, L.H., 2018. Globalization Without a Safety Net: The Challenge of Protecting Cross-Border Funding of NGOs. Minnesota Law Review, 102, pp. 1205-1271.

McFaul, M. and Mendelson, S.E., 2000. Russian Democracy – A U.S. National Security Interest. Demokratizatsiya, 8(3), pp. 330-353.

Muller, M.N. and Mitani, J.C., 2005. Conflict and Cooperation in Wild Chimpanzees. In: Slater, P.J.B., Snowdon, Ch.T., Roper, T.J et al. (eds). Advances in the Study of Behavior. Vol. 35. San Diego, CA: Elsevier, pp. 275-331.

NZSIS, 2023. New Zealand’s Security Threat Environment 2023. NZSIS. Available at: https://www.nzsis.govt.nz/assets/NZSIS-Documents/New-Zealands-Security-Threat-Environment-2023.pdf [Accessed 10 April 2024].

Rapport d’enquête n°1311, 2023. Rapport Fait au Nom de la Commission d’Enquête Relative aux Ingérences Politiques, Économiques et Financières n°1311 – Tome 1. Assemblée nationale, 1 June. Available at: https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/16/rapports/ceingeren/l16b1311-t1_rapport-enquete#_Toc256000008 [Accessed 10 April 2024].

Rapport Relatif, 2023. Rapport Relatif à l’activité de la délégation parlementaire au renseignement pour l’année 2022–2023. Senat.fr, 29 June. Available at: https://www.senat.fr/rap/r22-810/r22-810_mono.html [Accessed 16 May 2024].

Regan, P.M., 1998. Choosing to Intervene: Outside Interventions in Internal Conflicts. The Journal of Politics, 60(3), pp. 754-779.

The White House, 2022. National Security Strategy 2022. Whitehouse.gov, 12 October [pdf]. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf [Accessed 16 May 2024].

Titarenko, М., Leitner, М. et al. (eds.), 2007. VKP(b), Komintern i Kitai: Dokumenty / T. V. VKP(b), Komintern i KPK v period antiyaponskoi voiny. 1937 – mai 1943 [The VKP(b), the Comintern and China: Documents / Vol. V. VKP(b), the Comintern and the CPC during the Anti-Japanese War. 1937 – May 1943]. Moscow: ROSSPEN.

Wohlforth, W.C., 2020. Realism and Great Power Subversion. International Relations, 34(4), pp. 459-481.