The strategic partnership with China began in 1996 (just in time when this form of bilateral cooperation first became available), and it was considered by the leaders of Russia and China as a geopolitical rather than economic project. This interaction was supposed to be one of the key strokes in portraying Russia’s new international image. Developing privileged relations with Beijing would help to ensure Russia’s security in the East providing Moscow with the necessary space for maneuver in its relations with the United States and the West in general. The diversi?cation of foreign economic relations was only a part of these ambitious political objectives.

China became a net oil importer only in 1993, so its prospect as an economic partner was not quite clear at that time.

Of course, our approach to China has changed: its role in Russian foreign policy has been growing continuously. But although it is customary now to say about the sudden turn of Russia to the East, the peak of the political rhetoric concerning Russian-Chinese relations occurred precisely in the 1990s.

In December 1999, President Boris Yeltsin used his visit to Beijing to make his statement in front of President Jiang Zemin: “Yesterday, Clinton permitted himself to put pressure on Russia. It seems he has for a minute, for a second, for half a minute, forgotten what Russia is, that Russia has a full arsenal of nuclear weapons; therefore, he decided to ?ex his muscles.” Then, Yeltsin noted that Russia and China intend to uphold a multipolar world order: “We will dictate to the world how to live, and he is not alone.” [1]

Back then, Yeltsin’s statement, which was made in response to criticism on behalf of the United States and the European Union of the Russian military operation in Chechnya, did not cause a signi?cant reaction and, in fact, was seen as an oddity. Few people in the world took seriously Russian-Chinese rapprochement. Let us imagine what would happen today, if the Russian leader, in the presence of the Chinese President, threatened the United States with nuclear weapons saying that “we will dictate to the world how to live…”

In the 1990s, Western and many Russian analysts believed that cooperation between the two countries was reduced to the arms trade. As a matter of fact, the world had a fairly vague idea about the scope, the nature and the strategic objectives of Russian-Chinese military-technical cooperation. Nonetheless, gradual reorientation of Russia’s foreign economic relations toward the East began back then, with varying degrees of success.

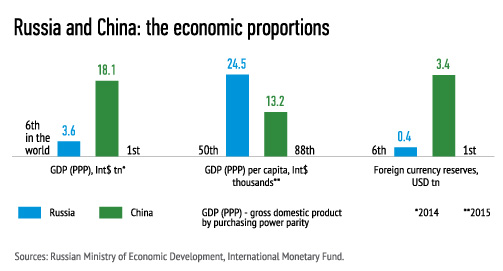

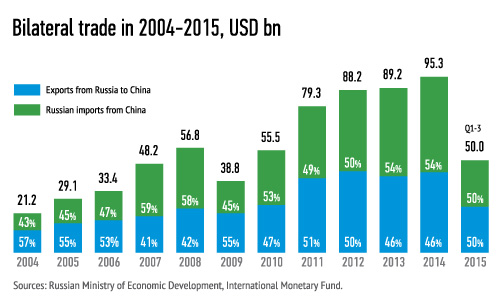

At that time, few believed that Russia would become less dependent on the EU and the United States through its cooperation with China. In 1999, bilateral trade amounted to $5.72 billion. Even though in the mid-1990s the Russian government embarked on a policy of building a strong economic foundation for the bilateral strategic partnership, Russia’s arms exports still remained the largest component of the trade turnover. It is only now that China has become Russia’s largest trading partner. In 1999, it was behind not only Germany, but also Ukraine, the United States, Belarus and Italy. Even in the crisis-ridden year of 2015, the monthly trade figures between the two countries was roughly equal to their annual trade in 1999.

The year 2015 with its fairly unusual statistics deserves special mention. Amid an overall $20 billion drop in bilateral trade, China’s weighted share in Russia’s foreign trade continued to grow (from 11.3 to 12.1 percent) at the same time as the EU’s share fell (from 48.1 to 44.8 percent). In other words, the process of reorientation of Russia’s economic ties toward the East has accelerated markedly during the crisis. Not only Western sanctions are to blame: other major countries, such as the United States and Japan, have stepped up their trade with Russia.

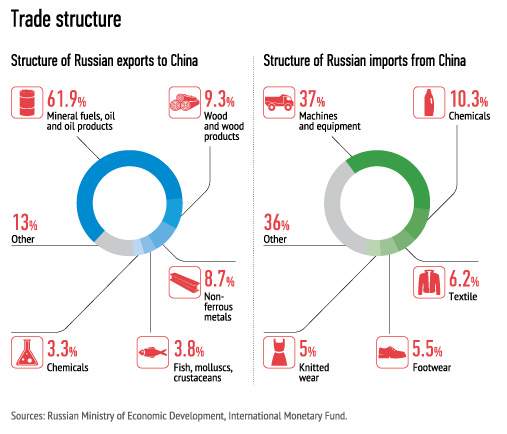

Admittedly, Russia’s ongoing diversi?cation of foreign economic relations through China provides only a limited economic and even more limited political effect. The unsatisfactorily slow pace of this turn is the first problem. The second problem concerns the structure of economic relations. The current model of bilateral trade has no future either for Moscow or for Beijing when looking long term. Russia’s role at the Chinese market is reduced to supplying raw materials, whereas Chinese high-tech manufacturers have less advantageous positions in Russia, as compared to their competitors from developed economies.

Even more importantly, this current model does not address the goals that were originally set early on in the strategic partnership. Due to the historical speci?cs of the Russia-China relations, economic cooperation lies in the hands of several major state-owned companies. In monetary terms, it is dependent on oil price fluctuations even more so than Russian oil exports. Falling oil prices first led to a decline in the financial indicators of Russian exports despite their physical growth, and then to a collapse of the ruble, which, in turn, triggered an even more drastic decline in China’s exports to Russia. For example, in 2015, Russia’s exports to China went down by 19.1 percent, while imports from China fell by 34.4 percent.

The predominance of fuel and energy and other commodities in Russian exports creates a landscape of limited interaction between our two countries. Bilateral relations affect a limited number of large mostly state-run companies; cooperation is politicized and usually involves extremely drawn-out negotiations at the highest level. In other words, bilateral economic ties are mainly controlled by a small group of government of?cials and business leaders, leaving little space for the development of human relations that are necessary for facilitating the exchange of information, ideas, or cultural achievements.

Outside the narrow range of companies operating in the sphere of energy and in the defense complex, other Chinese businesses know terrifyingly little about Russia. Short summaries of articles from American and British media are the primary, if not the only sources of information about the Russian economy. Even major Chinese businessmen are usually surprised to find out that Russia has no restrictions on capital movement, having dropped them in 2003.

With the exception of the Heilongjiang Province, most Chinese regions have no meaningful relations with Russia which would play any signi?cant role in their respective local economies. Furthermore, this limited relationship becomes dangerous within the current model of economic relations, as it has been built with a strong dependence on oil price fluctuations. This fact was corroborated by the 2009 crisis, which urged the authorities of Heilongjiang Province to diversify its foreign economic relations.

Outside of individual commodity industries and the defense sector, businesses in both countries are profoundly unaware of their respective capabilities and capacities. Instead, they disrespect, underestimate or show no sign of interest in each other, mainly because of a lack of information. Amid financial sanctions on Russia, Chinese banks have actually introduced additional restrictions on doing business with Moscow and additional checks for their counterparties. This solidi?ed the trade structure, where the Russian side focuses predominantly on fuel exports, which have long since been dubbed as a problem. Likewise, Chinese exports are far from being perfect, either, despite their “high-tech” nature, which one can surmise from a quick overview of customs statistics.

Chinese exports are dominated by western brands with negligible Chinese added value. For example, 3.25 million iPhones worth $2.14 billion [2] that were sold in Russia in 2014 were made in China. The fact is that these exports actually contributed just a few percent points to China’s GDP at best. Relatively unsophisticated consumer goods still dominate Chinese exports, which are doomed to become uncompetitive over time with growing labor costs in China.

The long-term decline on the oil market combined with China’s gradual loss of its role as a “global assembly shop,” which remains competitive due to its low labor costs, will preclude any effective growth based on such a model. In the long term, our countries may in fact experience a decline in economic relations, an outcome which will entail unwanted political implications.

Meanwhile, the current political and economic situation provides an important window of opportunity, making it very possible to take our relations to the next level. The weak ruble and the large amount of formal and informal technology sanctions on Russian industry make it possible to deploy industrial cooperation between the two countries on a wholly new level.

Technology sanctions on Russia are an important precedent, which other major emerging economies have taken into account. This is the ?rst time in the past decade that such signi?cant restrictions have been imposed on one of the world’s major economies. The sanctions on China following the events of 1989 were of far lesser scope.

Based on available information, we can assume that formal sanctions against Russia in the technology and ?nancial sector will stay in place for a long time. However, they will go hand in hand with signi? cant informal restrictions that are likely to remain in effect even after the formal sanctions have been lifted.

Sanctions are a standard response to foreign policy crises practiced by the United States and its allies. The likelihood of such a crisis is increasing year by year. China is faced with a similar set of problems due to rising tensions in the East China Sea and the South China Sea. As of now, China is pursuing the politics of a full-?edged great power, albeit with its own peculiarities. Therefore, China may ?nd itself ever increasingly confronted with the threat of sanctions from the West.

Thus, in early March 2016, the United States introduced restrictions on ZTE, a leader in the Chinese electronics industry, controlling 3.5 percent of the global smartphone market, and earning in excess $15 billion in 2015. [3] The sanctions were triggered by ZTE’s cooperation with Iran. This company depends on US-made components supplied by Qualcomm, and is now forced to obtain a permit for each purchase from the United States. ZTE’s main competitor – Huawei – is also operating under a recurring threat of sanctions.

Russia has now been living for over two years in a state of economic war waged against it. China is slowly but surely moving in that direction. It is surprising that this is happening in a situation where China’s foreign policy remains overall passive, and China is not involved in any crisis that would even remotely resemble the Ukraine conflict in terms of its severity. Nonetheless, the threat of sanctions on industry leaders who are not involved in defense production but whose turnover exceeds billions, if not tens of billions, of US dollars is becoming quite real. Companies such as ZTE are an important part of the Chinese economy. They are far more vulnerable to sanctions than companies engaged in commodities or manufacturing defense equipment production, and which form the backbone of the Russian economy.

The natural way to deal with this situation would be to look for alternative suppliers and, eventually, to establish a new system of industrial ties, the con?guration of which would largely follow the political situation. We’ve done most of this work in the defense and certain related industries. For decades, Russia has been part of the supply chain in the manufacturing of important parts for the Chinese defense industry. Russian companies act as R&D providers in developing finished products and individual units. They supply the Chinese with such components as engines, radars, homing devices and electromechanical components.

Against the backdrop of the Ukraine crisis, military-industrial cooperation has become a two-way street. Already in 2014, the first talks were held between Roskosmos and China’s CASIC space corporation regarding the supplying of Chinese electronic components for Russia’s space program. After German exports of marine diesel engines to Russia were put on hold, the new Russian project, number 21631, started producing small missile ships equipped with Chinese engines.

Similar processes are taking place in the non-military ?eld as well. As is known, shortly after the sanctions were imposed on Russia, contacts between the Russian oil and gas sector companies and Chinese manufacturers of drilling rigs and other oil industry equipment intensi?ed.[4] However, contacts in the civil industry remain chaotic and irregular.

Of course, expecting a different outcome amid the economic crisis in Russia and a general decline in the investment climate globally in 2014–2015 is an unlikely proposition. Economic dif?culties further aggravate a situation for cooperation between the two countries, when there is a general shortage of information, lack of experience and fear of doing business in an unfamiliar environment.

The likelihood of formal or informal sanctions against Chinese companies engaged in joint industrial projects with our country represents an additional problem. The United States has developed a model for coercing Asian companies based in countries that are not parties to the sanctions against Russia to actually comply with such sanctions anyway. The US of?cials meet with representatives of the companies cooperating with Russia and openly intimidate them with unspeci?ed consequences should they continue to engage in such undesirable cooperation.

Given that the political will to speed up the expansion of bilateral relations is observed mostly at the upper tiers of the political leadership both in Russia and China, these tactics are more than effective with regard to Chinese companies. Should the United States impose sanctions against Chinese businesses on a broader basis, the latter are likely to use even more caution. Therefore, the question arises: who exactly can be our partner in China in promoting industrial cooperation, and what organizational and legal forms should the cooperation take?

This question has a fairly simple and straightforward answer: China’s military-industrial complex is our most promising partner in promoting cooperation in nonmilitary industries.

The Chinese defense industry is represented by 10 giant state corporations, namely, Norinco Group, China South Industries Group Corporation (specializing in weapons for ground troops), AVIC (aviation equipment), CASC and CASIC (missiles and space), CSSC and CSIC (shipbuilding and naval equipment), CNNC and CNECC (nuclear equipment and materials, and construction of nuclear facilities). CETC is a major manufacturer of military-grade electronics. The China Academy of Engineering Physics, which is in charge of all nuclear weapons design and development is another defense corporation that is part of a league of its own.

Why do these companies hold promise as partners? Unlike its Russian counterpart, the Chinese defense industry boasts a much more diversi?ed manufacturing base. Purely military output within major military-industrial conglomerates accounts for no more than 10-15 percent of revenues. So, we are talking about a community of gigantic diversi?ed industrial companies which manufacture a wide range of civilian products, including many types of machines and equipment for the oil and gas industry, in addition to industrial and consumer electronics, software, telecommunications equipment, rail and sea transport, and even automobiles. They are experienced in carrying out complex foreign-based engineering projects.

China’s defense manufacturers continue to lag behind their Russian counterparts in terms of purely military output and are much less successful on the global arms market. But when it comes to diversi?cation and their share of output for civilian use, they leave their Russian colleagues far behind. The share of goods for the civilian population manufactured by Russia’s largest defense company Rostekh has so far amounted to just 28 percent, but long-term plans estimate an increase to 50 percent. [5]

Why should Russia be interested in these companies under current circumstances? Primarily, because they are also under the sanctions or they are under a constant threat of sanctions. Strictly speaking, a ban on military-technical cooperation with China was introduced by the European Union and the United States in 1989 following the Tiananmen Square protests, and has been in place until now without any prospects for cancellation. In addition to US restrictions on military and technical cooperation, there are others on the exportation of dual-purpose products to China, and let’s not forget the special powers of the US President, who can ban any commercial activity of these companies in the United States (this ability is used selectively).

There’s also a vast body of US sanctions on these corporations and their subsidiaries imposed as a punishment for their alleged cooperation with Iran in missile technology or nuclear sphere. In most cases, it concerns the import and export departments of missile companies, such as CPMIEC, which sell missiles made by CASIC and CASC. In still other cases, the sanctions apply to entire organizations, such as Norinco Group.

In addition to this already extensive body of formal sanctions, the Chinese military-industrial conglomerates are confronted with much wider informal restrictions, including equipment purchases and cooperation with US partners. These companies have considerable experience in operating under sanctions and circumventing them. They make use of the opportunities offered by Chinese and foreign businesses interested in having in?uential Chinese partners.

In some cases, defense companies, such as Norinco, tend to become China’s economic agents in charge of conducting business with the countries subjected to sanctions or countries with speci?c business environments.

Norinco has in fact carried out underground subway construction projects in Tehran. The company also has expertise in railway electri?cation, as well as solar and conventional power engineering. Based on its long-term and diversi?ed business in the Middle East, Norinco has established its own oil division named Zhenhua Oil, which is engaged in oil upstream and downstream operations.

Other defense companies have developed a similar pattern. For example, CETC was involved in implementing telecommunication projects in Egypt. AVIC International, AVIC’s investment arm, is involved in development projects in a number of countries around the world.

Russian state and private companies have experience working with Chinese defense industry enterprises in the civilian sphere. For example, Roselektronika, which is part of Rostekh, participated in LED projects while working in conjunction with China’s CETC, which specializes in military electronics. In 2010, En + signed a strategic cooperation agreement with Norinco, which was to involve, in particular, the supplying of large quantities of aluminum.

Now, based on the experience of cooperation with these companies – both in military and civilian spheres – it would make sense to build a new industrial cooperation system based on the strengths of both countries’ industrial potential. The defense industry has the necessary experience, labor and expertise to do so. Most importantly, defense industry enterprises on both sides can enlist private businesses in their projects and establish better communication channels with political leaders. Chinese defense industry companies can serve as a bridge to reach out to China’s high-tech civilian enterprises, with which they maintain unpublicized symbiotic relations. CETC’s cooperation with world-renowned corporations such as ZTE and Huawei is one such prominent example.

Thus, there is now a need to create new special mechanisms for promoting Russian-Chinese industrial cooperation capable of taking our relations to the next level. These mechanisms should be fully adapted to function even amid an economic war, and ensure long-term cooperation in the ? eld of industrial cooperation and the funding of joint projects. This cooperation could follow in the steps of industrial cooperation between China and Iran.

Stepping up cooperation between the defense industries of Russia and China in the sphere of civilian production as part of an initiative approved by the leaders of the two countries can be the starting point for developing such relations. Initially, it is imperative, therefore, to recognize at the national level that industrial integration needs to be a major political goal for both Moscow and Beijing. Without resolving this problem, all efforts to merely build up trade won’t have the desired effect on our ability to change the nature of bilateral relations. It is also important to realize that neither party alone will be able to build the independent research, technological or industrial potential, capable of allowing full-scale competition with the United States in the manufacturing of military or consumer products.

Consequently, any industrial integration policy should be enshrined in a joint document similar to the renowned declaration signed in May of 2015, uniting the Eurasian Economic Union with China’s Silk Road Economic Belt project. The document outlines the main objectives and principles of industrial integration, including the fundamental issues of protecting intellectual property rights.

The parties should also agree that in certain areas of industrial cooperation that are not directly related to defense, there will be no special publicly funded import substitution efforts with regard to Russian- or Chinese-made products. The adoption and subsequent implementation of such a document would greatly increase mutual trust, actually, much better than the annual Russian-Chinese military exercises, and without calling undue attention or being perceived as an attempt to establish a military-political alliance.

The existing mechanism of annually convening intergovernmental commissions and industry-speci?c subcommissions to address this problem is inef?cient, because this way one can monitor only the implementation of a very limited number of projects. In its current form, the Russia-China Machinery/Equipment/Innovative Products Chamber of Commerce created in 2007 is an association of Russian and Chinese companies that is fairly limited in terms of its goals and capabilities.

Initially, it will be imperative to create a permanent Russian-Chinese coordination center in charge of industrial integration, which will be responsible for collecting, organizing and making available to potential customers information about the capabilities of R&D institutions and industrial companies in both Russia and China. Such a coordination center could be established by a special intergovernmental agreement, which will, among other things, outline the issues related to protecting the information that is used by this center. These efforts should focus on the precise identi?cation of areas in which each side has a competitive advantage. At the same time, it is imperative to create a specialized joint Russian-Chinese financial unit to finance the industrial integration program, which should be immune to any pressure from the United States or the EU, as well as to ensure an acceptable level of information protection.

This coordination center can ensure cooperation between enterprises and research centers operated by the military-industrial complexes of the two countries but under civilian programs. On the one hand, its initial goal may be the creation of a new non-military production site in Russia with Chinese investments, technology and parts and, on the other hand, it could help the Russian companies in overcoming the bottlenecks of China’s industrial capacity, primarily, in the ?eld of R&D and software development, as well as in supplying Russian-made products, which can potentially replace imports from developed countries.

In the near future, Russia and China will receive a favorable window of opportunity for deploying such cooperation. A major undervaluation of the ruble against the RMB and other major currencies makes manufacturing in Russia more competitive and makes new projects easier to launch. But this window of opportunity may close within the next five to seven years, as oil prices resume their growth and Russia’s relations with the West stabilize. This is quite a short-lived opportunity for rolling out major technically challenging projects.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.