For citation, please use:

Royce, D.P., 2026. The U.S. Pursuit of NATO Expansion to Russia’s Borders: Motivation and Timing. Russia in Global Affairs, 24(1), pp. 15–41. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2026-24-1-15-41

While NATO’s expansion to Central Europe might have had some realpolitik merit, and it did limited damage to Russian interests and thus to international stability, NATO’s expansion to the Baltics, Ukraine, and Georgia (BUG) was different, in that it did (or threatened, insofar as successful) serious harm to Russia’s security and vital identitarian interests.

This article contends that, for the U.S., NATO’s BUG expansion is/was motivated, justified, and/or compelled by Cosmopolitan-Liberalism (Cosmopoliberalism) and the desire to contain Russia (Section 1).

This Cosmopoliberal Anti-Russian BUG Expansion (CL-AR-BUG-E) was seemingly always latent within U.S. thinking. It was officially adopted on 18 October 1993 and (more expansively) on 13 October 1994. It was foisted upon the U.S.’s allies at NATO’s January 1994 summit and (more comprehensively) in NATO’s 3 September 1995 Study on Enlargement. And it was even established as U.S. law in September 1996 and October 1998. (Secs.2.1-2.7) While the Anti-Russian component of CL-AR-BUG-E is left unstated in most of the analyzed material, it is present in the most important document of all, along with a warning to keep silent about it (Sec.2.8).

Thus, virtually from the moment that the Cold War ended, the U.S. was implicitly committed to (and soon actively engaged in) a Drang nach Osten that targeted:

- The Baltics (intent by 13 October 1994, action by spring 1996, accession on 29 March 2004) (Sec.3.1).

- Ukraine (intent by 13 October 1994, action by 2001) (Sec.3.2).

- Georgia (intent by January 2001, action by late 2003) (Sec.3.3).

And this was a project led and driven by the U.S., which actually faced reluctance and some degree of opposition from many of its NATO allies, especially those in Western Europe (Sec.4).

-

Defining CL-AR-BUG-E

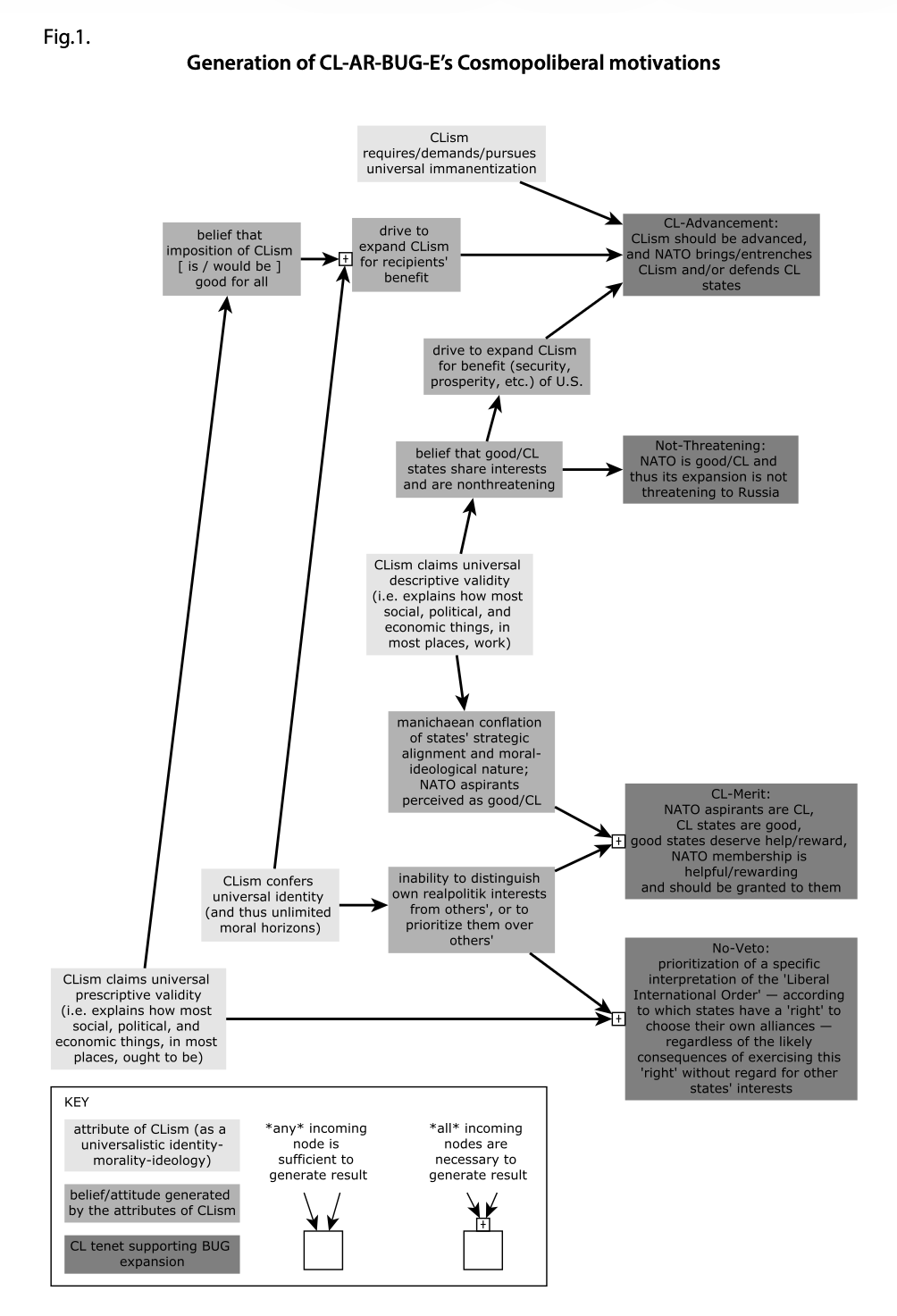

The four main Cosmopoliberal tenets of CL-AR-BUG-E are as follows:

Not-Threatening: NATO is good/Cosmopoliberal and thus its expansion is not threatening to Russia. E.g., “democracies on the border of Russia [due to NATO’s expansion] are in its [i.e., Russia’s] interest” (Bush).[1] “…Russians need to get over their neuralgia on this subject… there are no would-be aggressors to be rebuffed” (Strobe Talbott, Deputy Sec.State for the FSU).[2]

CL-Advancement: Cosmopoliberalism should be advanced, and NATO brings/entrenches Cosmopoliberalism and/or defends Cosmopoliberal states. For example, expansion “strengthen[s] democracy against future threats” (Clinton),[3] establishes a “Europe whole and free” (Bush),[4] and “anchor[s] democracy and stability in Europe” (Obama).[5]

CL-Merit: Good/Cosmopoliberal NATO aspirants deserve help/reward, NATO membership is helpful/rewarding and should be granted to them. For example, “no European democracy should be excluded from ultimate consideration” for membership (Clinton),[6] and “every European nation that struggles toward democracy and free markets and a strong civic culture must be welcomed into Europe’s home” (Bush).[7]

No-Veto: Prioritization of a specific interpretation of the ‘Liberal International Order’—according to which states (especially “free”[8] and “democratic”[9] ones) have a ‘right’ to choose their own alliances[10]—regardless of the likely consequences (including for the U.S.’s own realpolitik interests) of exercising this ‘right’ without regard for other states’ interests. Hence “no country outside NATO will have a veto” (Clinton),[11] “no non-NATO country has a veto,”[12] “Russia cannot have a veto” (Obama),[13] etc.

The Not-Threatening tenet leads to nonperception of Russian opposition to BUG expansion, or disbelief in the genuineness of that opposition, or belief that Russia can be disabused of it. That, in turn, blocks the recognition that BUG expansion would affect Russian perceptions and behavior in ways that would likely have net-negative consequences for the realpolitik interests of NATO’s current members. CL-Advancement and CL-Merit morally-ideologically compel expansion. And No-Veto forbids expansion’s realpolitik restraint.

Aside from these Cosmopoliberal tenets, an Anti-Russian motivation (to contain and weaken Russia) would (at least given sufficient disregard for realpolitik considerations) also motivate NATO’s expansion up to Russia’s borders.

The result of all this is BUG expansion—an objective that may be:

(1) expressed by explicitly targeting some or all of BUG;

(2) included within a broader commitment to expanding into the FSU, into all of Europe, or limitlessly (without any geographic/realpolitik constraints).

Not-Threatening, CL-Advancement, CL-Merit, and No-Veto are all explained and predicted by the Theory of Particularism/Universalism (Royce, 2025). Specifically, they are generated by the U.S.’s universalistic Cosmopoliberalism as follows:

These four tenets motivate universalistic behavior that—to the extent that these motives, and not the anti-Russian one, are at play—only incidentally impinges upon Russia’s vital interests, through NATO’s expansion into BUG. (It thus is Type 1 Impingement per the Theory of Particularism/Universalism.)

An alternative possibility is that the Cosmopoliberal tenets are not genuinely held or genuinely motivating the U.S., but rather are being cited by the U.S. as justification for expansion that is actually driven by purely Anti-Russian motives. This probably is happening in some cases, especially instances of communication with the public, U.S. allies, or Russia itself. And it is particularly plausible in the case of the No-Veto tenet, which would then be nothing more than an (unsurprising) unwillingness to compromise with Russia on a policy directed against Russia. However, as will become apparent in this analysis, the Cosmopoliberal tenets of CL-AR-BUG-E are also voiced within entirely internal discussions at the highest levels of the U.S. government. (These documents have been ‘forcibly’ declassified only in the last few years, pursuant to Freedom of Information Act requests—and often lawsuits.) Thus, Cosmopoliberalism is also exerting a genuine motivational effect, one that is substantial and independent of the (certainly also present) Anti-Russian motivation.

Regardless, the U.S.’s statement of Cosmopoliberal tenets is significant in that it indicates an intent to carry out BUG expansion—whether the tenets are genuine motivation for that expansion, propagandistic cover for an actual Anti-Russian motivation, or both.

-

CL-AR-BUG-E’s Crystallization after the Cold War

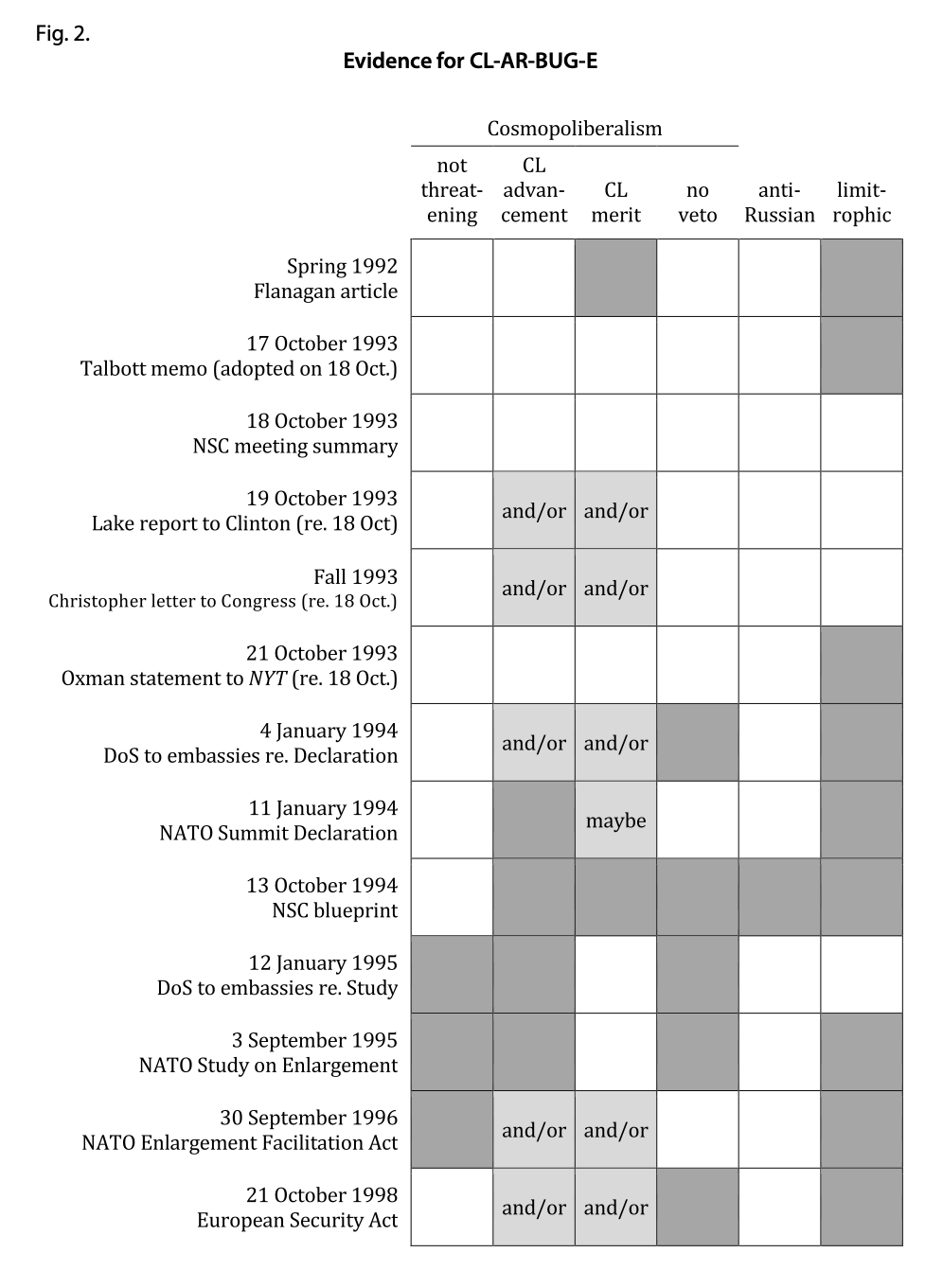

This article now traces the crystallization of CL-AR-BUG-E—consisting of Not-Threatening, CL-Merit, CL-Advancement, No-Veto, Anti-Russian, and BUG—in the key documents, decisions, and laws of the U.S. and NATO that defined the alliance’s expansion.

2.1. The George H. W. Bush Administration

The U.S. began seeking some form of NATO expansion as soon as that was made possible by the Soviet bloc’s collapse (Shifrinson, 2020, p. 22-25). While CL-AR-BUG-E may or may not have been consciously adopted by the Bush I Administration, its underlying attitudes and beliefs were present from the outset.

A good look at these attitudes and beliefs was provided by Stephen Flanagan, then the Associate Director of the Policy Planning Staff of the Department of State (DoS),[14] who played a major role in NATO expansion discussions in 1992, and who was “granted permission by the State Department to publish a paper… that outlined some of our deliberations within the Bush I Administration on… enlargement” (the same considerations were also “outlined” for NATO allies in October 1992 (Flanagan, 2019, pp. 103-105)).

The paper’s crucial passage read: “If NATO is an alliance of democracies with historical ties and common values [CL-Merit], what is the basis for excluding other such countries in Europe [BUG] who request membership? …states would exclude themselves… by their failure to realize or uphold the expanded Alliance principles. …perhaps ultimately membership… might be offered on the basis of the degree to which a given society had completed its transformation” (Flanagan, 1992).

In 1992, these CL-AR-BUG-E tendencies did not yield a concrete policy. This is hardly surprising, given that BUG had only become independent within the last few months, and the Bush I Administration was “contending with a number of more pressing issues” in 1992, including the upcoming election. Yet “a quiet debate and growing consensus on enlargement continued throughout the end of the Bush Administration” (Flanagan, 2019, pp. 103-105).

2.2. The NSC Decision for Expansion (18 October 1993)

On 17 October 1993, Strobe Talbott sent a memo to Sec.State Warren Christopher which, according to Talbott’s memoir, contended: “Our strategic goal… was to integrate both Central Europe and the former Soviet Union [BUG] into the major institutions of the Euro-Atlantic community. …instead of designating who the first new members would be, the [NATO] Brussels summit in January [1994] should commit the alliance to ‘an evolutionary process’ in which… the Partnership for Peace would be ‘an important first stage,’ leading to the admission of new members in the future” (Talbott, 2003, pp. 99-100).

According to Talbott (2003, pp. 99-100), “Chris agreed with this approach, and… it carried the day” at the next day’s NSC meeting, which concluded (in language very similar to that of Talbott’s CL-AR-BUG-E-promoting memo) that: “The [January 1994] summit should make a commitment in principle to NATO expansion but without articulating criteria, specifying timing[,] or [naming] likely candidates for membership… The path to membership should be described as an ‘evolutionary process’ with active participation in PfP as an important step…”[15]

Just over a year later, on 2 January 1995, Talbott alluded to 18 October 1993 as the point of decision, writing that Sec.Defense William Perry’s position (skepticism of expansion, and preference for PfP as a true alternative to it) is “not our Administration policy—and hasn’t been for just over a year now.”[16] And in his memoir, Talbott (2003, p. 111) again identified the decision to expand, expressed publicly by Clinton on 12 January 1994 in Prague, as having been actually made “the previous October.”

It is true that Talbott’s 17 October definition of expansion—as explicitly extending into the FSU, thus including BUG—was not repeated in the summary of the 18 October meeting. But it soon became clear that the agreed-upon expansion was indeed Cosmopoliberal and BUG.

National Security Advisor Anthony Lake, in a 19 October report to Clinton,[17] and Sec.State Christopher, in a subsequent letter to Congress,[18] said that the U.S. had decided that the upcoming NATO summit should issue a “statement of principle[s]” that NATO will enlarge to “include new democracies in Europe’s east” [CL-advancement and/or CL-Merit].

And on 21 October 1993, a “senior aide to Secretary of State Warren Christopher” (this aide was actually Assistant Sec.State for Europe Stephen Oxman (Goldgeier, 1999, p. 184))—informed the New York Times that: “The United States has decided to support an expansion of NATO that could eventually include Russia, the countries of Eastern Europe[,] and other former members of the Warsaw Pact [BUG]… …the issue [of expansion] was discussed at [an NSC] meeting within the past week and… Clinton approved the decision on Tuesday [19 October] night.”[19]

2.3. The NATO Declaration (11 January 1994)

In accordance with the 18 October 1993 decision, the DoS on 4 January 1994 directed its embassies in Europe to tell European governments that the U.S. was pursuing CL-AR-BUG-E: “We anticipate that the NATO Summit will issue a statement of principle that the Alliance expects and would welcome expansion to include new democracies to its east [CL-Advancement and/or CL-Merit], as part of an evolutionary process. Our approach is inclusive and non-discriminatory. It does not draw new lines in Europe. No state is a priori excluded from eligibility for possible membership [unlimited including BUG]. NATO consideration of expansion issues will take the interests of all European states into account. But be subject to a ‘veto’ by none [No-Veto].”[20]

And, unsurprisingly, the 11 January 1994 NATO Summit Declaration contained most of what the U.S. had ordered (minus No-Veto): “The fuller integration of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and of the former Soviet Union [BUG] into a Europe whole and free [CL-Advancement] cannot be successful without the strong and active participation of all Allies… We expect and would welcome NATO expansion that would reach to democratic states to our East…[CL-Advancement and/or CL-Merit].”[21]

2.4. The NSC Blueprint (13 October 1994)

On 13 October 1994, Nat.Security Advisor Anthony Lake sent an NSC working paper titled “Moving Toward NATO Expansion” to President Clinton.[22]

The next day, Clinton read the paper and wrote, on its front page, that it “looks good.” According to the NSC’s Director for Europe, Alexander Vershbow (2019, p. 430-432), it “served as the vehicle for gaining interagency consensus,” it “became the blueprint for efforts led by the State Department to build a consensus within NATO,” and “over the next three years, the United States followed this roadmap almost to the letter.” In short, it largely represented and/or crystallized U.S. policy. And it contained most of CL-AR-BUG-E:

CL-Advancement: “To… underpin the democratic reform process in [Central and Eastern Europe], we need to create a perspective that Partnership for Peace will lead to Alliance membership for some…members.”

CL-Merit: In deciding how to expand, NATO should “stick to ‘precepts’—democracy, market economy, responsible/good-neighborly security policies.”

No-Veto: “…an institutionalized relationship between NATO and Russia… should include a mechanism for consulting with Russia on NATO or NATO-led military operations… but without giving [the] Russians a veto over NATO decisions.”

BUG: The U.S. should pursue “an expanded NATO, including the major CEEs [i.e., Central and Eastern European states] who live up to our precepts, with the prospect of further expansion to those not admitted in the first tranche.” More specifically, the “possibility of NATO membership for Ukraine and [the] Baltic States should be maintained; we should not consign them to a gray zone or a Russian sphere of influence.” Another point, about the need to “keep the membership door open for Ukraine, [the] Baltic States, Romania and Bulgaria,” was emphasized by Clinton by hand.

And the paper held that the U.S., at the upcoming 1 December 1994 NATO FMs’ meeting, should secure a “formal review to establish [the] Alliance policy framework for expansion, including [its] political/security rationale, military requirements…”

2.5. The NATO Study (3 September 1995)

At the 1 December 1994 meeting, a Study on Enlargement was indeed ordered.

And on 12 January 1995, the DoS provided its European embassies and NATO mission with a “draft outline” of what “the U.S. believes should emerge from the Alliance’s internal deliberations on enlargement.”[23] This included three of the Cosmopoliberal tenets.

Not-Threatening: The “alliance is purely defensive, not a threat to any country.” “By extending stability, enlargement will benefit both new members and those who do not join.”

CL-Advancement: Enlargement will “accelerate [the] process of building a new Euro-Atlantic community” by “helping consolidate democratic reforms.”

No-Veto: “No non-member has a veto over membership.”

When the Study on NATO Enlargement was published nine months later, on 3 September 1995, it contained all of the above, plus BUG.[24]

Not-Threatening: The 1 December 1994 Communique had stated that “enlargement should strengthen the effectiveness of the Alliance, contribute to the stability and security of the entire Euro-Atlantic area” [emphasis added].[25] But now the Study asserted that NATO expansion is a priori nonthreatening, and seemingly betrayed some frustration with Russia’s inability to understand that: “…the Alliance has made it clear that the enlargement process[,] including the associated military arrangements[,] will threaten no-one… enhancing security and stability for all;” enlargement “would threaten no one”; enlargement “will…threaten no-one” [emphases added].

CL-Advancement: “Enlargement will contribute to enhanced stability and security… by encouraging and supporting democratic reforms… …reinforcing… integration and cooperation in Europe based on shared democratic values.”

No-Veto: “NATO enlargement would [i.e., will] proceed in accordance with the provisions of the various OSCE documents which confirm the sovereign right of each state to freely seek its own security arrangements, to belong or not to belong to international organisations, including treaties of alliance. No country outside the Alliance should be given a veto or droit de regard over the process and decisions.” “…there can be no question of ‘spheres of influence’ in the contemporary Europe.” “NATO decisions… cannot be subject to any veto or droit de regard by a non-member state.”

BUG: “It will be important… not to foreclose the possibility of eventual Alliance membership for any European state in accordance with Article 10 of the Washington Treaty.”

2.6. U.S. Legislation

Finally, later in the decade, CL-AR-BUG-E was also enshrined in legislation.

The NATO Enlargement Facilitation Act (passed 353-65 in the House[26] and 81-16 in the Senate,[27] and enacted within the 30 September 1996 omnibus[28]) stated that it is U.S. policy to “actively assist the emerging democracies in Central and Eastern Europe in their transition so that such countries may eventually qualify for NATO membership” [CL-Advancement and/or CL-Merit]. NATO’s admission of “emerging democracies” “will not threaten any nation” [Not-Threatening]. In particular, “in order to promote economic stability and security in Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Moldova, and Ukraine,” the U.S. “should continue and expand its support” for their participation “in activities… qualifying for NATO membership”, and expansion “should not be limited to consideration of… Poland, Hungary, [Czechia], and Slovenia” [BUG].

And the European Security Act (passed unanimously by the House[29] never voted on as a distinct item in the Senate, and enacted within the 21 October 1998 omnibus[30]) declared that the U.S. “should ensure that NATO continues a process whereby all [emphasis added]…emerging democracies in Central and Eastern Europe that wish to join NATO will be considered for membership… as soon as they meet the criteria” [BUG, CL-Advancement and/or CL-Merit]. And the U.S. should make no commitment to Russia that would provide any “authority to delay, veto, or otherwise impede deliberations and decisions of the North Atlantic Council… including… with respect to… the admission of additional members to NATO” [No-Veto]. In particular, the Baltics (along with Romania and Bulgaria), “upon complete satisfaction of all relevant criteria[,] should be invited to become full NATO members at the earliest possible date,” and they were made eligible for military assistance under the Program to Facilitate Transition to NATO Membership [BUG].[31]

2.7. The Anti-Russian Motive

The above analysis has presented only the four Cosmopoliberal tenets, and the BUG ambitions, of CL-AR-BUG-E, with no mention of the Anti-Russian motive. That is partly because the latter is, indeed, rarely stated in the analyzed documents.

However, it can still be found on occasion. For instance, in a 5 February 1996 memo to Sec.State Christopher (not analyzed above), Talbott said that, throughout the FSU, “we have assiduously avoided rhetoric or activities that could be construed… as neo-containment” of Russia. Yet he suggested warning Russia that its objections to NATO expansion will only “raise the profile of the ‘hedge’ (i.e., anti-Russian) rationale for expansion” [parentheses original].[32] Meaning that such a rationale did, in fact, exist.

And the crucial 13 October 1994 NSC NATO-expansion blueprint did state an Anti-Russian purpose (alongside the various Cosmopoliberal tenets already identified above).

While targeting the Baltics and Ukraine, as described above, it strongly implied that expansion would exclude Russia. The “possibility of membership in the long term for a democratic Russia should not be ruled out explicitly” [emphasis added]. And NATO should produce a “statement of new, more ambitious goals for [an] expanded NATO relationship with Russia in addition to PFP… implicitly foreshadowing [an] ‘alliance with the Alliance’ as an alternative [for Russia] to [the] membership track…”

Moreover, expansion was described as having an “‘insurance policy’/‘strategic hedge’ rationale (i.e., neo-containment of Russia)” [parentheses original]. But this rationale should be “kept in the background only, rarely articulated.”

And yet, one more statement of the Anti-Russian purpose actually followed immediately, on 15 October 1994, when Nick Burns (the NSC’s Director for Eurasia) asked Talbott to “Note, in particular, the [NSC plan’s] emphasis [on] trying to figure out how to deal with Ukraine and the Baltics. In my view, and [in the view of Nat.Security Advisor Lake], these [not Visegrad] are the real fault lines… as we seek to expand NATO, i.e. they are the countries that could actually face a Russian threat in the future. While they may not be the prime early candidates for NATO, they cannot be relegated to a Russian sphere.”[33] [Emphases added.]

2.8. Summary

The analyzed material’s evidence, for the various components of CL-AR-BUG-E, can be summarized as follows:

-

CL-AR-BUG-E’s Concrete Implementations

The general doctrine of CL-AR-BUG-E quickly crystallized into specific policies of expansion (often conceptualized and/or defended on a Cosmopoliberal basis). This crystallization was virtually instant in the cases of the Baltics and Ukraine, and took about ten years in the case of Georgia.

3.1. The Baltics

Following the 13 October 1994 NSC blueprint’s statement of intent to admit the Baltics, the U.S. Government, from mid-1995 through mid-1996, gave increasingly unambiguous signals to the Baltics of that desire/intent.[34] These culminated in a 12 June 1997 statement, from Talbott to the three Baltic ambassadors, that the U.S. “since 1994 [has] known that enlargement should not exclude any emerging democracy [CL-Merit], including for reasons based on history [or] geography” (Sarotte, 2021, p. 481). Talbott promised that the U.S. “will not regard the process of NATO enlargement as finished or successful unless or until the aspirations of the Baltic states are fulfilled” (Asmus, 2002, p. 236).

The U.S. even made its intentions clear to Russia. When Primakov told Talbott on 15 July 1996 that Russia’s red lines “include such issues as the Baltics and Ukraine”, Talbott responded that: “if… you mean that you’re not prepared to accept the Baltic states’ and Ukraine’s eligibility for NATO membership in the future, then we’ve got a collision of red lines… …one of our red lines is… and will continue to be… that no country is going to be ruled out of eligibility, certainly not by some other country [No-Veto].”[35]

In fact, a July 1996 internal DoS paper identified one of Russia’s objectives, in negotiations on the NATO-Russia charter, as “rul[ing] out Baltic and Ukrainian membership in NATO”—and it described the U.S. strategy as: “persuad[ing] [the] Russians that enlargement is a fact and that blocking or splitting tactics will not work; …[and] that realism means [the Russians] abandoning or significantly modifying their coming-in goals.”[36]

Accordingly, when Primakov, in early March 1997, tried to ensure that Clinton would, in an upcoming summit with Yeltsin, commit to not admitting any former Soviet states into NATO, Talbott dodged the strategic substance of Russia’s concerns by responding with what Primakov labeled “high theory and legalisms.” Talbott, according to his own recounting: “reminded [Primakov] that the U.S. had never recognized the Baltics’ incorporation in[to] the USSR and that we didn’t accept Russia’s right to block any of its neighbors from joining any international organization or alliance [No-Veto]” (Talbott, 2003, p. 236).

In fact, when Clinton and Yeltsin met in Helsinki in mid-March 1997, Yeltsin offered acquiescence to limited NATO expansion in exchange for an “oral agreement” between the two presidents that NATO would keep out of former Soviet states. Clinton refused, saying that he would not be “vetoing any country’s eligibility for NATO, much less letting you or anyone else do so” and that any commitment to limit NATO expansion “would violate the whole spirit of NATO [No-Threat, No-Veto, unlimited including BUG]” (Talbott, 2003, pp. 238-241). Clinton “did not just say ‘no’ to Russian opposition to eventual Baltic or Ukrainian membership in NATO; he explained why ‘no’ is the only right answer, even from the Russian point of view [No-Threat].”[37]

Already by spring 1996, the U.S. had begun work on a Baltic Action Plan, completed in the summer, that would provide bilateral and multilateral military assistance to the Baltics in order to help them “meet the Alliance’s accession requirements.”[38]

And as the first round of NATO expansion approached, the USG concluded that restricting its scope would ensure a second round soon, thereby “protecting the Baltic states and ensuring that they, too, had a chance to join NATO down the road” (Asmus, 2002, p. 216). Thus, the U.S. went to the 8-9 July 1997 NATO Summit in Madrid with the mission of restricting membership invitations to Poland, Czechia, and Hungary, preventing the placement of Romania and Slovenia ahead of the Baltics (as sought by the Latin states), and securing a general Open Door principle (contrary to British reluctance). With the support of the Germanic states, this was accomplished (Asmus, 2002, pp. 245-248). On 12 July 1997, Clinton said: “we’ve made a very clear statement that every democracy in Europe who wishes to join should be eligible to join at the appropriate time [CL-Merit] and that we will take regular reviews, the first one in 1999. And that applies to the Baltics as well as other countries.”[39]

In the meantime, as Deputy Assistant Sec.State for Europe Ron Asmus wrote to Talbott on 20 July 1997, the U.S. would move from its “passive NATO enlargement strategy” (ensuring “that the Baltics are not excluded”) to a “more active strategy designed to create the circumstances under which we could bring the Baltics into NATO.”[40] By 26 November 1997 (when a Latvian official accurately predicted that his state’s membership would be endorsed in the upcoming document[41]), the U.S. had decided to publicly and officially support Baltic NATO membership in a Baltic Charter (signed with the three Baltic states on 16 January 1998) stating that the U.S. “welcomes the aspirations and supports the efforts of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to join NATO,” that “NATO’s door [will] remain open to new members,” and that “no non-NATO country has a veto over Alliance decisions” [No-Veto].[42]

Finally, on 24 April 1999, the Baltics were issued Membership Action Plans (MAPs)[43]—the recipients of which, excepting Bosnia, had always been offered membership sooner or later—that were indeed followed by invitations on 21 November 2002[44] and accession on 29 March 2004.[45]

3.2. Ukraine

As for Ukraine, the U.S.’s intent to induct it into NATO was, as with the Baltics, confirmed in the NSC blueprint on 13 October 1994. Details of the U.S.’s intent and actions—the latter beginning by 2001—are available separately (Royce, 2024a, 2024b).

3.3. Georgia

Finally, in the case of Georgia, CL-AR-BUG-E apparently did not immediately translate into intent, let alone action. Instead it seems that, as Georgia was so far from the center of Europe and NATO, its accession was simply not actively considered for many years. Yet, as NATO expanded eastward—the Black Sea states of Romania and Bulgaria, alongside the Baltics, were offered MAPs in 1999—this changed, and Georgian accession was adopted as a natural component of CL-AR-BUG-E, seemingly without debate and almost automatically.

At the January 2001 hearing on Colin Powell’s nomination to be Sec.State, Senator Gordon Smith asked what the Bush Administration would do about the Russian government’s “efforts to intimidate Georgia.” Powell responded, in writing, that “we will support Georgia’s efforts to become a reliable regional partner, firmly integrated into Euro-Atlantic institutions”[46]—which could refer only to NATO, since Georgia was already fully part of the OSCE.

On 13 September 2002, the Georgian Parliament instructed the government to “launch… an integration process into NATO,”[47] and Georgian leader Eduard Shevardnadze accordingly declared the goal of NATO membership at the 21-22 November 2002 NATO Summit in Prague.[48]

The U.S. responded by immediately endorsing and assisting this shift in Georgia’s policy. Beginning in 2003 (Fiscal Year, 2004), the National Endowment for Democracy began supporting the NGO “Georgia for NATO”, which would “educate the public about the military, political, and economic reforms that are the prerequisites for NATO membership” and “the necessity for such reforms.”[49]

The U.S. also provided public and private indications of its support for Georgian membership. For instance, at a 10 May 2005 press conference, Bush told then Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili that “we look forward to working with you to meet [the] obligations” required for NATO membership.[50]

Throughout 2006, the U.S. sought a MAP for Georgia[51]—and in the course of this campaign, told allies like Romania,[52]

Bulgaria,[53] and Turkey[54] of its support for Georgia’s full membership—but ultimately had to settle for an Intensified Dialogue, granted on 21 September 2006. The U.S. continued pursuing a MAP for Georgia, now alongside Ukraine, in 2008—an effort that nearly succeeded, and that is detailed in a prior article regarding Ukraine (Royce, 2024a, 2024b).

-

CL-AR-BUG-E Was Sought by the U.S., Not by Its NATO Allies

Finally, it should be clarified that CL-AR-BUG-E was very much a U.S. project, and actually had to be imposed upon many NATO allies who were neutral or outright opposed.

For instance, in the early 1990s, Germany’s Chancellor and FM were skeptical of any enlargement at all, while Defense Minister Volker Ruhe, often seen as one of the initiators of NATO expansion, actually supported expansion specifically to Poland and perhaps the rest of Visegrad—but not beyond (Goldgeier, 1999, p. 34). According to Asmus (2002, p. 300), it was “the Clinton Administration and other allies” that insisted “that all countries from the Baltic to the Black Sea were potential members” [emphasis original].

A 1 October 1994 DoS cable reported the UK’s view of the Baltics as “militarily indefensible” and “far from possible NATO membership,” and its fear that their accession “would be unacceptable to the Russians in the foreseeable future.”[55]

In April 1995, President Clinton expressed uncertainty that: “the Russians will be isolating themselves[,] rather than isolating us[,] if they continue to play hard-to-get on NATO. The Europeans are vulnerable to being split from us on this. They’re probably sympathetic to some of the arguments [that] they’re hearing from the Russians.”[56]

A 29 July 1996 DoS paper concurred, noting that key allies, especially Germany and France, had doubts about the U.S.-preferred pace of expansion, and might be “susceptible to Russian splitting/delaying/blocking tactics.”[57]

Indeed, on 27 February 2001, Senator Biden noted that: “whether I am in France or Belgium or Spain or Italy or Germany, talk of the Baltics becoming members of NATO is by and large very much at odds with [the West Europeans’] view of expansion and where it should take place, if any takes place. [The West Europeans] view the Baltics as not defensible. [The Baltics] would be lost if there was a conflict, very quickly, and [the West Europeans] view it as a stick in the eye to the Russians, going back to our differing views as to how important it is to have the acquiescence of—or at least not the open hostility of—Russia.”[58] (The U.S., apparently, did not view that as important at all.)

And if many West Europeans were skeptical of Baltic accession, they were terrified of Ukrainian and Georgian accession. For instance, they dragged their feet in 2006-2008 when the U.S. sought MAPs for Ukraine and Georgia. (Although it seems that the U.S. would eventually have had its way, were it not for the Russo-Georgian War (Royce, 2024a, 2024b).)

(This does raise a question. The West Europeans have twice now been proven right in their opposition to NATO’s BUG expansion and the U.S.’s anti-Russian course more generally. (For instance, in 2005, the French warned the Americans that “the question of Ukrainian accession to NATO remain[s] extremely sensitive for Moscow, and… if there remained one potential cause for war in Europe, it was Ukraine.”[59]) So why then have they responded not by redoubling their commitment to their own position, but by abandoning it precisely when it is most clearly justified and most badly needed? Perhaps because their elites and even general populations have undergone a drastic transformation in consciousness and worldview over the last few decades: away from national identity and sovereignty; towards English, Americanization, and Cosmopoliberalism.)

-

Conclusion

Thus, in accordance with the Theory of Particularism/Universalism, NATO’s BUG expansion was/is motivated by the U.S.’s Cosmopoliberalism; “based mainly on liberal principles” (Mearsheimer, 2018, p. 178); driven by “liberal universalism” (Sakwa, 2015). This motive was/is probably genuine. The U.S., in public and in communications with allies and Russia itself, might indeed have reason to invent Cosmopoliberal camouflage for a policy that is actually only anti-Russian. But this article has also analyzed internal high-level U.S. documents—namely Lake’s 19 October 1993 report to Clinton, and the crucial 13 October 1994 NSC blueprint—which reference not just No-Threat, but also the more dispositive tenets CL-Merit and/or CL-Advancement.

Yet alongside Cosmopoliberalism, an anti-Russian purpose—not so much Realpolitik as unprudently aggressive—certainly has propelled BUG expansion. The sparseness of evidence for this motive does not at all indicate its actual absence. The motive was clearly stated in the crucial 13 October 1994 blueprint, alongside a warning—evidently carefully followed—to keep silent about it.

This analysis, then, has revealed that a policy of Cosmopoliberal Anti-Russian BUG Expansion existed inertly from when (or even before) the USSR collapsed, took shape on 18 October 1993, crystallized on 13 October 1994, targeted the Baltics and Ukraine by that date, and extended to Georgia by January 2001. The motivations and timing of this policy are significant for several reasons.

First, Cosmopoliberalism and an anti-Russian purpose were sufficient to launch the U.S.’s pursuit of NATO’s BUG expansion, virtually as soon as this was made possible by the USSR’s collapse—even though (or precisely because) Russia was then at its weakest and most subservient to the U.S.

Second, BUG expansion’s Cosmopoliberal motive is likely responsible for the impotence of Russian diplomacy (including the December 2021 ultimatum) that appeals to (and/or threatens) the U.S.’s realpolitik interests (Royce, 2024c). The U.S. has been guided not by its own realpolitik interests, but by its Cosmopoliberal identity-morality-ideology, on which it cannot compromise. The threat or use of force (directly in support of South Ossetia and the Donbass) has therefore been the only thing able to stop expansion.

Third, that will continue to be the case, and any future U.S. commitment to refrain from expansion will be probably unattainable and definitely unreliable, insofar as the U.S. remains driven by Cosmopoliberalism. If expansion is a moral imperative, membership is an inalienable right, etc., then a treaty abrogating those things must be morally-ideologically unacceptable and—if signed—illegitimate and nonbinding. Conversely, if and insofar as the U.S.’s Cosmopoliberalism diminishes, it may be possible for Russia to contain expansion through diplomacy, compromise, and treaty. But such mechanisms will collapse if the U.S.’s Cosmopoliberalism resurges, and thus should be implemented only (1) alongside the establishment of a favorable military-strategic situation and alongside a continuing readiness to use force as necessary, and/or (2) given full confidence that the U.S.’s rejection of Cosmopoliberalism is real (not superficial or declarative) and permanent (not subject to reversal by the whims of a single president or by a several-percentage-point swing in voter sentiment).

[1] George W Bush, 2 April 2008. The President’s News Conference With President Traian Basescu of Romania in Neptun, Romania. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/the-presidents-news-conference-with-president-traian-basescu-romania-neptun-romania

[2] Strobe Talbott, 19 September 1997. The End of the Beginning: The Emergence of a New Russia. Speech at Stanford University. Quoted in Asmus, 2002, p. 231.

[3] Bill Clinton, 28 October 1996. Remarks to the Community in Detroit, Michigan. Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents 32.43. Specifically pp. 2137-2144.

[4] George W Bush, 15 June 2001. Address at Warsaw University. Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents 37.24. Specifically pp. 914-918.

[5] Barack Obama, 11 March 2008. NATO Enlargement and Effectiveness. Hearing. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110shrg44537/html/CHRG-110shrg44537.htm

[6] Bill Clinton, 7 July 1997. Remarks Following a Meeting With Members of Congress and the National Security Team and an Exchange With Reporters in Madrid, Spain. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PPP-1997-book2/html/PPP-1997-book2-doc-pg917.htm

[7] George W Bush, 15 June 2001. Address at Warsaw University. Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents 37.24. Specifically pp. 914-918.

[8] Daniel Fried, 10 September 2008. Protocols to the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949 on the Accession of the Republic of Albania and the Republic of Croatia. Hearing. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110shrg44538/html/CHRG-110shrg44538.htm

[9] Philip Gordon, 28 July 2009. The Reset Button Has Been Pushed—Kicking Off a New Era in US-Russian Relations. Hearing. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111hhrg51655/html/CHRG-111hhrg51655.htm

[10] E.g.: Baltic Charter, 16 January 1998. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PPP-1998-book1/html/PPP-1998-book1-doc-pg71.htm

Philip Gordon, 28 July 2009. The Reset Button Has Been Pushed—Kicking Off a New Era in US-Russian Relations. Hearing. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111hhrg51655/html/CHRG-111hhrg51655.htm

Daniel Fried, 10 September 2008. Protocols to the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949 on the Accession of the Republic of Albania and the Republic of Croatia. Hearing. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110shrg44538/html/CHRG-110shrg44538.htm

Hillary Clinton, 13 January 2009. Hearing on Confirmation as Secretary of State. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg54615/html/CHRG-111shrg54615.htm

[11] Bill Clinton, 28 October 1996. Remarks to the Community in Detroit, Michigan. Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents 32.43. Specifically pp. 2137-2144.

[12] Baltic Charter, 16 January 1998. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PPP-1998-book1/html/PPP-1998-book1-doc-pg71.htm

[13] Barack Obama, 11 March 2008. NATO Enlargement and Effectiveness. Hearing. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110shrg44537/html/CHRG-110shrg44537.htm

[14] Press Secretary of the White House, 1 August 1997. https://clintonwhitehouse6.archives.gov/1997/08/1997-08-01-stephen-flanagan-appointed-special-assistant-to-the-president.html

[15] Summary of Conclusions for Meeting of NSC Principals Committee, October 18, 1993. Quoted in: Asmus, 2002, p. 51.

[16] Strobe Talbott, 2 January 1995. Untitled Memo to Sec.State Warren Christopher. Quoted in: Asmus, 2002, p. 98.

[17] Anthony Lake. 19 October 1993. Memo to President Clinton. Quoted in: Sarotte, 2021, p. 177.

[18] Warren Christopher, nd. Letter to Members of Congress. Quoted in: Goldgeier, 1999, p. 60.

[19] Elaine Sciolino, 21 October 1993. U.S. to Offer Plan on a Role in NATO for Ex-Soviet Bloc. The New York Times.

[20] Warren Christopher, 4 January 1994. NATO: Briefing on Partnership for Peace. Cable to all European embassies. C06544777. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11350/DOC_0C06544777/C06544777.pdf

[21] NATO, 11 January 1994. The Brussels Summit Declaration. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_24470.htm?mode=pressrelease

[22] Anthony Lake, 13 October 1994. Moving Toward NATO Expansion. Memo to President Clinton. Clinton Library Box 481, Folder 9408265, 2015-0755-M, pp. 71-76 (PDF pagination). https://goo.su/fCGDU

[23] Warren Christopher, 12 January 1995. US Draft Outline of NATO Presentation on Expansion; Guidance for January 12 SPC/R. Cable to the US Mission to NATO and all European embassies. C06323567. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-03979/DOC_0C06323567/C06323567.pdf

[24] NATO, 3 September 1995. Study on NATO Enlargement. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_24733.htm

[25] NATO, 1 December 1994. Final Communiqué issued at the Ministerial Meeting of the North Atlantic Council. https://www.nato.int/docu/comm/49-95/c941201a.htm

[26] House Vote #338 of 1996, 23 July 1996. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/104-1996/h33

[27] Senate Vote #245 of 1996, 25 July 1996. https://senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_votes/vote1042/vote_104_2_00245.htm

[28] HR3610(104) Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Act of 1997, 30 September 1996. https://www.congress.gov/bill/104th-congress/house-bill/3610/text/pl

[29] HR1758(105) European Security Act of 1997, 11 June 1997. https://congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/house-bill/1758/all-actions?s=1&r=53

[30] HR4328(105) Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act of 1999, 21 October 1998. https://congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/house-bill/4328

[31] 22 USC 1928 North Atlantic Treaty Organization. http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:22 section:1928 edition:prelim)

[32] Strobe Talbott, 5 February 1996. Memorandum to the Secretary: Your Meeting with Primakov in Helsinki. Memo to Sec.State Christopher. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_L_Apr2023/FL-2017-13804/DOC_0C09000058/C09000058.pdf

[33] Nick Burns, 15 October 1994. Note for Strobe Talbott, Jim Collins. C06835794. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_L_Nov2021_C/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06835794/C06835794.pdf

[34] U.S. Embassy Vienna, 2 August 1995. DEPSEC Talbott Discusses Baltics/Estonia with Finns and Estonian Foreign Minister. Cable to USDEL OSCE. C06700554. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Apr2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06700554/C06700554.pdf

U.S. Embassy Vienna, 15 September 1995. Acting Secretary Talbott’s Sept. 1 Meeting with Estonian P.M. Vahi: Focus on Russia and Security Concerns. Cable to USDEL OSCE. C06699302. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Apr2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06699302/C06699302.pdf

U.S. Embassy Vienna, 16 April 1996. The Deputy Secretary’s Meeting with Estonian Foreign Minister Kallas, March 25. Cable to USDEL OSCE. C06697970. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_Jun2019_2020/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06697970/C06697970.pdf

U.S. Embassy Vienna, 24 May 1996. Deputy Secretary’s May 24 Meeting with Lithuanian DEFMIN Linkevicius: Focus on NATO Enlargement. Cable to USDEL OSCE. C06722131. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Dec2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06722131/C06722131.pdf

Warren Christopher, 1 July 1996. Meeting with Presidents Meri of Estonia, Ulmanis of Latvia and Brazauskas of Lithuania. Cable to Embassies Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius. C06698302. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_Jul2019_2020/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06698302/C06698302.pdf

Warren Christopher, 9 September 1996. Acting Secretary Briefs Baltics on Action Plan. Cable to Embassy Tallinn. C06698268. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_Jul2019_2020/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06698268/C06698268.pdf

[35] Strobe Talbott, 16 July 1996. Readout of 15 July 1996 Conversation between Strobe Talbott and Yevgeniy Primakov. Memo to Sec.State Warren Christopher. C06570196. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11926/DOC_0C06570196/C06570196.pdf

[36] No author, 29 July 1996. NATO-Russia: Objectives, Obstacles, and Work Plan. DoS paper. C06570185. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11899/DOC_0C06570185/C06570185.pdf

[37] U.S. Mission to NATO. 24 March 1997. Official Informal. Cable to Sec.State Madeleine Albright, C06703619. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/Litigation_Sep2019/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06703619/C06703619.pdf

[38] Warren Christopher, 9 September 1996. Acting Secretary Briefs Baltics on Action Plan. Cable to Embassy Tallinn. C06698268. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/FOIA_Jul2019_2020/F-2017-13804/DOC_0C06698268/C06698268.pdf

[39] Bill Clinton, 12 July 1997. Exchange With Reporters Prior to Discussions With Prime Minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen of Denmark in Copenhagen. In: Federal Register Division of the National Archives and Records Service. 1999. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, Book 2, p. 953.

[40] Ronald Asmus, 20 July 1997. The Hanseatic Strategy. Memo to Strobe Talbott. C06570058. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11994/DOC_0C06570058/C06570058.pdf

[41] No author, 26 November 1997. Baltic presidents to meet Clinton in January. Agence France-Press.

[42] 1997. Exchange With Reporters Prior to Discussions With Prime Minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen of Denmark in Copenhagen. In: Federal Register Division of the National Archives and Records Service. 1999. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, Book 2, p. 953.

Ronald Asmus, 20 July 1997. The Hanseatic Strategy. Memo to Strobe Talbott. C06570058. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11994/DOC_0C06570058/C06570058.pdf

No author, 26 November 1997. Baltic presidents to meet Clinton in January. Agence France-Press.

A Charter of Partnership Among the United States of America and the Republic of Estonia, Republic of Latvia, and Republic of Lithuania, 16 January 1998. http://1997-2001.state.gov/www/regions/eur/ch_9801_baltic_charter.html

[43] NATO, 24 April 1999. An Alliance for the 21st Century: Summit Communique. Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Washington, DC on 24th April 1999. https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/WH/New/NATO/statement3.html

[44] NATO, 21 November 2002. NATO Invites Seven Countries to Accession Talks. https://www.nato.int/docu/update/2002/11-november/e1121c.htm

[45] NATO, 29 March 2004. Seven New Members Join NATO. https://www.nato.int/docu/update/2004/03-march/e0329a.htm

[46] Colin Powell, 17 January 2001. Nomination of Colin L Powell to be Secretary of State. Senate hearing. https://www.congress.gov/107/chrg/shrg71536/CHRG-107shrg71536.htm

[47] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia, nd. Information on NATO-Georgia Relations. https://mfa.gov.ge/ევროპული-და-ევრო-ატლანტიკური-ინტეგრაცია/მნიშვნელოვანი-მოვლენების-ქრონოლოგია-NATO.aspx?lang=en-US

[48] Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies, nd. Timeline: NATO Georgia Relations. https://gfsis.org.ge/media/download/GSAC/resources/NG_Timeline.pdf

[49] NED Annual Reports: 2004. https://www.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/annualreports/2004-ned-annual-report.pdf

- http://ned.org/publications/annual-reports/2006-annual-report/eurasia/description-of-2006-grants/georgia

- http://ned.org/publications/annual-reports/2007-annual-report/eurasia/description-of-2007-grants/georgia

- http://ned.org/publications/annual-reports/2008-annual-report/eurasia/description-of-2008-grants/georgia

- http://www.ned.org/publications/annual-reports/2009-annual-report/eurasia/description-of-2009-grants/georgia

[50] George Bush, 10 May 2005. The President’s News Conference With President Mikheil Saakashvili of Georgia in Tbilisi, Georgia. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/the-presidents-news-conference-with-president-mikheil-saakashvili-georgia-tbilisi-georgia

[51] State Department cables 05PARIS6125, 06ROME933, 06ROME1023, 06ANKARA1790, 06PARIS2195, 06TALLINN318, 06BUCHAREST573, 06PRAGUE343, 06REYKJAVIK125, 06PARIS2252, 06ANKARA1877, 06THEHAGUE822, 06BERLIN1494, 06PARIS4214, 06PARIS5423, aavailable on Wikileaks.

George W. Bush, 5 July 2006. Remarks Following Discussions With President Mikheil Saakashvili of Georgia and an Exchange With Reporters. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-following-discussions-with-president-mikheil-saakashvili-georgia-and-exchange-0

George W. Bush. 10 July 2006. Interview With Foreign Journalists. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/interview-with-foreign-journalists

Congressional Research Service, 6 March 2009. Georgia [Republic] and NATO Enlargement: Issues and Implications. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20090306_RS22829_e73867b1b6414471263abcd8330e6b19da8969a9.html

[52] Embassy Bucharest, 15 March 2006. DAS Pekala’s visit to Romania highlights Black Sea issues, EU accession, corruption battle. Cable. 06BUCHAREST447. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06BUCHAREST447_a.html

[53] Embassy Sofia, 14 March 2006. Bulgarians discuss Iraq, joint bases, crime/corruption, and democracy promotion. Cable. 06SOFIA372. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06SOFIA372_a.html

[54] Embassy Ankara, 5 October 2006. Turkey and GMF–seeking wider Black Sea Western strategy. Cable. 06ANKARA5817. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06ANKARA5817_a.html

[55] Warren Christopher, 1 October 1994. Official-Informal No.62. Cable to Embassy Riga. C06551636. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11854/DOC_0C06551636/C06551636.pdf

[56] Strobe Talbott, 13 April 1993. Note to the Secretary. Memo to Sec.State Warren Christopher. C06698878. https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/20263-national-security-archive-doc-16-note

[57] Unspecified author, 29 July 1996. NATO-Russia: Objectives, Obstacles, and Work Plan. DoS paper. C06570185. https://foia.state.gov/DOCUMENTS/MDR_May2018/M-2017-11899/DOC_0C06570185/C06570185.pdf

[58] Joseph Biden, 27 February 2001. The State of the NATO Alliance. Hearing of the Subcommittee on European Affairs of the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107shrg71538/html/CHRG-107shrg71538.htm

[59] Embassy Paris, 9 September 2005. EUR A/S Fried’s September 1 Meetings with Senior MFA and Presidency Officials on Improving Relations with Europe. Cable. 05PARIS6125. https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/05PARIS6125_a.html

_________________________

Academic Sources

Asmus, R., 2002. Opening NATO’s Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New Era. Columbia University Press.

Flanagan, S., 1992. NATO and Central and Eastern Europe: From Liaison to Security Partnership. The Washington Quarterly, 15(2), pp. 141-151.

Flanagan, S. 2019. NATO From Liaison to Enlargement: A Perspective from the State Department and the National Security Council 1990-1999. Ch. 4. In: Hamilton, D,, and Spohr, K., (eds.) Open Door: NATO and Euro-Atlantic Security After the Cold War. Brookings Institution Press.

Goldgeier, J., 1999. Not Whether But When: The US Decision to Enlarge NATO. Brookings Institution Press.

Mearsheimer, J., 2018. The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities. Yale University Press.

Royce, D., 2024a. Путь к столкновению: Стремление США к экспансии НАТО на Украину: хроника тридцати лет [Collision Course: The U.S.’s Pursuit of NATO Expansion into Ukraine: A 30-Year History]. Rossiya v globalnoi politike, 22(3), pp. 210-234. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6439-2024-22-3-210-234

Royce, D., 2024b. The U.S.’s Pursuit of NATO Expansion into Ukraine Since 1994. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(3), pp. 46-70. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-3-46-70

Royce, D., 2024c. The History of Russian Diplomatic Opposition to NATO Expansion into the Baltics, Ukraine, and Georgia. Russian Politics, 9(3), pp. 366-401. https://brill.com/view/journals/rupo/9/3/article-p366_3.xml

Royce, D., 2025. The Behavior of Particularistic and Universalistic States. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(1), pp. 70-99. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-1-70-99

Sakwa, R. 2015. The New Atlanticism. Russia in Global Affairs, 13(3).

Sarotte, M., 2021. Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate. Yale University Press.

Shifrinson, J., 2020. Eastbound and Down: The United States, NATO Enlargement, and Suppressing the Soviet and Western European Alternatives, 1990–1992. Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(6-7), pp. 1-31.

Talbott, S., 2003. The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy. Random House.

Vershbow, A., 2019. Present at the Transformation: An Insider’s Reflection on NATO Enlargement, NATO-Russia Relations, and Where We Go from Here. Ch. 18. In: D. Hamilton and K. Spohr (eds.) Open Door: NATO and Euro-Atlantic Security After the Cold War. Brookings Institution Press.