Abstract

This article studies the European identity of modern Russia and EU countries. The main idea of the article is that the existence of the European Union today is largely determined by the spirit of “Europeanness” and by relations between European countries and the EU. The article examines the correlation between the notions of ‘Europe’ and the ‘European Union,’ and analyzes the results of the opinion polls conducted to measure peoples’ feeling of “Europeanness” in EU countries and Russia. Over the past twenty-five years, the EU and Russia have seen all kinds of relations—from official assurances of sharing common values, goals and interests and public support for the idea of Russia’s integration with the EU to openly competitive and, later, hostile relations. The Ukraine crisis has brought growing differences to a head, and subsequent mutual sanctions have clearly demarcated the boundaries of “Europeanness” and prospects for rapprochement or estrangement between the former strategic partners. The issue of “belonging to Europe” today determines the political choice and development vectors of EU and non-EU countries. The peculiarity of European identity is that residents of EU countries, just like many Russians, do not believe that the EU is the embodiment of an “ideal Europe,” although they agree that European integration positively influences the implementation of the idea of an “ideal Europe.”

Keywords: Russia, Europe, European Union, Europeanness, European identity

FROM GEOGRAPHY TO POLITICAL ECONOMY AND THE POLICY OF SYMBOLIC IDENTITY

This article does not pursue the goal of defining “European identity” or “the feeling of attachment to Europe.” My task is modest: to show what meaning is given to this notion and what factors influenced the understanding of European identity in EU countries and Russia in the last twenty-five years. This task can be achieved by analyzing an explicitly expressed feeling of attachment to Europe in political elites, and by studying the results of public opinion polls in EU countries and Russia. Comparing the results of those polls in EU countries and Russia with actual events makes it possible to identify the factors that increased or reduced the feeling of supranational identity and its substantive interpretation.

European identity is a supranational category and exists both in EU countries (although they feel their attachment to this supranational community differently) and in countries that are not members of the EU and have no membership prospects. Discussing Europe requires taking into account several aspects of this notion: 1) geographical under which it is understood as part of the world; 2) political seen through European organizations operating on the basis of treaties, norms, institutions and obligations; and 3) cultural/civilizational under which it is perceived as some imaginable community of countries and peoples; belonging to it is not fixed but rather suggests self-identification of peoples, countries and individuals. Geographical borders in Europe changed over time, and disputes still continue over whether certain countries belong to Europe or not. Europe’s eastern and southern borders are most disputable and unstable as they affect, apart from the purely geographical dimension, cultural and civilizational identity. Klaus Eder referred to these differences as the issue of Europe’s “soft,” or imaginary, borders (geographical and cultural-civilizational) and “hard,” or institutionalized, borders within the EU (soft/imaginary boundaries and institutional (hard) Europe which we call the European Union) (Eder, 2006: 256).

The problem of European identity lies in the fact that since the early 1990s this notion has shifted from the sphere of geography and cultural/civilizational coordinates to the sphere of political economy, legal obligations and symbolic affiliation, determined by the institutional frameworks of political organizations, which has created new dividing lines in Europe. The problem of European identity, seen in terms of politics and law, ceases to be a subject for purely scholastic discussions, since the answer to the question of European/non-European identity today is a matter of political and even ideological choice for countries, political leaders and peoples. That is why it is so important to analyze how different aspects of European identity correlate, what factors influence the feeling of Europeanness, and what consequences political elites and peoples living in Europe may face when they make a choice in favor of European identity or waive it.

Relations between Europe, the EU and individual European countries, including Russia, can be illustrated by a diagram using subsets proposed by mathematician Leonhard Euler, known as “Eulerian circles.” It is common knowledge that Europe is part of Eurasia and the political map of Europe comprises 50 countries, as well as disputed territories, unrecognized or partially recognized states, and dwarf and island states. Twenty-eight countries are members of the European Union, and another seven countries have been officially accepted as candidates for EU membership. Some other countries do not have candidate status but would like to join the EU and now cooperate with it under the European Neighborhood Policy (Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, and Armenia). Some European countries are not EU members, yet they closely cooperate with it in the fields of economy, political relations, and internal and external security (Switzerland, Norway, and Iceland). Forty-seven countries of Europe are members of the Council of Europe (with the exception of Belarus and Kosovo), although geographically not all of them are situated in Europe (Azerbaijan and Georgia, for example). Geographically, Russia is a European country, and its most important (politically, demographically and economically) part is located in Europe. However, a large territory of Russia is in Asia; so, in a geographical sense, Russia is more a “Eurasian country” than a purely European one. We should also mention the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), which comprises all European countries, plus the United States and Canada. Twenty-seven European countries are members of NATO, which is led by a geographically non-European country, the United States, and which also includes Canada.

By visualizing the political architecture of Europe (political Europe) as Eulerian circles, we can define the boundaries of affiliation of different countries and their intersections, using their formal membership in these organizations as the basis. This methodology allows us to identify “the most European countries” which are integrated in all these subsets (for example, France, Germany, and Italy), and countries that are least represented in European organizations (Belarus). We can single out the most inclusive European organizations (the OSCE and the Council of Europe) and those with limited membership (NATO and the EU). The latter two organizations are almost identical, with some exceptions. Besides the non-European U.S. and Canada, NATO includes Turkey, Albania, Norway, Iceland, and Montenegro, but these are not EU members. However, these countries are either official candidates for EU membership (Albania, Montenegro, and Turkey) or earlier considered applying for membership but then decided otherwise (Norway and Iceland). Some EU countries maintain neutral status and are not NATO members—Sweden, Austria, Finland, and Malta. Twenty-one European countries are members of NATO’s Partnership for Peace program, including neutral EU countries, EU candidate countries, Eastern Partnership countries, and countries that do not have formal relations with the EU (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan).

Importantly, the configuration of all these European organizations has changed significantly over the past twenty-five years and set an identity vector by formalizing relations between European countries. The factor that played a major role in these changes was symbolic affiliation with Europe as a space of shared values and an ideal community striving for the ideals of peace, development, protection of human rights, and universal security based on the principles of cooperation, good neighborly relations, and openness. These ideas were expressed by European leaders in the “Greater Europe” and “Common European Home” concepts at the turn of the 1990s. The enthusiasm inspired by those projects persisted, despite armed conflicts in Europe and on its periphery, many of which were frozen, with no prospect of being settled in the foreseeable future. Unresolved conflicts with a high potential for escalation have influenced the present-day perception of the European political space and the choice of ways to solve problems. In this sense, the issue of European/non-European identity has a pronounced political and value dimension and depends on the choice of political leaders and people voting for or against an “ideal Europe.”

THE EUROPEAN UNION AS A POLITICAL PROJECT FOR CREATING AN “IDEAL EUROPE” AND THE POLICY OF EUROPEANIZATION

I would like to share a long quote from the book Re-Visioning Europe: Frontiers, Place Identities and Journeys in Debatable Lands by German anthropologist Ullrich Kockel (Kockel, 2010), which, in my opinion, accurately conveys the meaning and context of discussions about “Europe,” its borders, the substance of this concept, and its perception both from within and by external actors over the past quarter of a century: “Once upon a time, not all that long ago, there was a place called ‘Europe,’ which some of us may still remember. Like other parts of the world, it had its share of problems, but most people were, nonetheless, happy enough there, while many from elsewhere have long been eager to move to Europe, even as we are told that there may not be, nor ever have been, such a place at all. Until not so long ago, it seemed to be a fairly obvious matter where and what this Europe was. […] While it may have meant rather different things to different people, there was at least a consensus that it did exist somewhere. But that consensus evaporated in the final decades of the twentieth century.” Kockel writes that “for the Russians it was a kind of cultural alter ego,” while “the French and Germans would expect Europe to be a place where, at long last, they might live together in peace.”

This jocular and somewhat provocative reasoning reflects the main idea of the book—the search for meanings that peoples living in or outside Europe read into the notion of ‘Europe.’ The main source of debates is the project to create a “United Europe” within the European Union which, as the author rightly says, does not exhaust the idea of being ‘European,’ although it claims so (Kockel, 2010: 1-2).

The early 1990s were a period when two major processes in Europe coincided in time and space. They determined inseparable dynamics of events and the interdependence of actors. The first process was the deepening of European integration and its transition to a qualitatively new level, which required strengthening the European Union’s supranational institutions and creating a political community of Europeans or a kind of nation within the EU framework. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 introduced “EU citizenship” and the EU began to shape “European identity” to enhance EU citizens’ feeling of attachment to a supranational Union. EU institutions viewed European identity as a means to bring heterogeneous regions and countries closer together within the framework of the EU citizenship concept. In addition, it was believed to solve the problem of democratic deficit and strengthen the legitimacy of supranational institutions through more active participation of EU citizens in European construction (Shore, 2000: 45).

It was then that a gradual transition began from “EU identity” to “European identity.” This actual substitution of notions broadened the political content of the term ‘European’ and fixed European identity as attachment to the EU at the level of individual and group identity. It should be noted that researchers of European identity have always noted this distinction. It is noteworthy that Eurobarometer surveys conducted in 2018 already used two independent categories—“attachment to the EU” and “European identity”—to denote the feeling of belonging to Europe (Standard Eurobarometer, 2018).

Another process, which coincided with the deepening of integration of twelve (and since 1995, fifteen) countries of western, northern and southern Europe, was the disintegration of the Eastern bloc as a military-political alliance and socio-economic system based on a common ideology. The disintegration of the Eastern bloc and the Soviet Union, as well as reforms in these countries, created a situation where nearly thirty countries in the post-Soviet space had to choose new political, social, economic, and ideological bases and define guidelines for future development. In the early 1990s, the EU became such a guideline in Europe. At that time, countries of Central and Eastern Europe, including post-Soviet countries, saw the EU-15 as a realized ideal of a peaceful and prosperous Europe. The Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty) says that “any European State may apply to become a Member of the Union” (Treaty, 1992: 138), without mentioning geographical boundaries. The terms of admission were elaborated by the European Council in 1993 and 1995 and are known as the Copenhagen criteria (Accession criteria, 2018). The Copenhagen criteria determine the value and regulatory requirements applicant countries should meet, including their commitment to creating a political, economic, and monetary union.

Modern Russia and countries that have joined or plan to join the EU call this vector of internal transformation “Europeanization” as a way of harmonizing national norms and standards with those of the EU. Petr Kratochvil described Europeanization which the EU used in relation to countries that wanted to join or closely cooperate with it as a “substantial change in policy practices and discourse” (both of the elite and society) with regard to their own identity and place in the world, and as a result of normative pressure or attractiveness of the European Union (Kratochvil, 2008: 398). The Europeanization of candidate countries proceeded as a gradual change of their legislation and practices used by public institutions before their formal accession to the EU, and the adoption of thousands of regulations governing internal and international activities of the EU, which were called acquis communautaire. According to the accession criteria, before admission, candidate countries should coordinate “the conditions and timing of the candidate’s adoption, implementation and enforcement of all current EU rules (the ‘acquis’),” grouped in 35 chapters (Chapters, 2016).

Russia was “Europeanized” through the EU’s active participation in the country’s reform through technical assistance programs and expert and financial support for the reforms of the administrative, judicial, and electoral systems. In 1996, Russia joined the Council of Europe, to which end it had to reform its judicial and law enforcement systems. Russia’s joining the Bologna Process, aimed at creating a European Higher Education Area, required major changes in its secondary and higher education systems, which was formally accomplished by 2010.

With regard to Russia, the Europeanization policy was complemented with a policy of “normalizing” the country, with a distinct focus on transforming the former hegemon of the Eastern bloc into a “normal” European state without any privileges or special rights in relations with the EU and former Eastern bloc countries. Russia’s relations with the EU and NATO very quickly made it realize that it would never be admitted to either alliance and that it would always remain outside them as a not quite “ordinary” or “normal” state. Russia’s admission to NATO as a full member was “inconceivable” as it was a former adversary, while for the EU Russia was too vast and distinct to be digested. In addition, it would have created “a serious imbalance in the Union” (Marquand, 2009: 49).

THE FEELING OF ATTACHMENT TO EUROPE IN EU COUNTRIES

Many European researchers note that the emergence of the EU and its efforts to shape European identity as EU identity, on the one hand, have created a great deal of (formal) certainty about the feeling of attachment to Europe; on the other hand, they have provoked constant debates about whether or not the notion of Europe should be limited to the EU and whether ‘Europe’ and ‘EU’ are interchangeable notions. It is absolutely clear that the deepening of European integration has required defining the identity of the EU as a political community and pursuing an EU identity policy. However, it is important to remember that the EU is not a state, although it has clear signs of a state: extensive common legislation, supranational bodies, external borders, a common currency and a common market (although the internal border and common currency regimes are not comprehensive). The EU does not collect taxes, which means it cannot be a guarantor of social policy or an effective regulator of social processes. EU countries retain their national identity and continue to support it as the basis of the political unity of their nations.

The development of the European Union for a long time was based on the logic of economic and political goal-setting, and European identity was taken as a given which exists and helps solve the set political and economic tasks. This perception was facilitated by the existence of the Iron Curtain which made it possible to build identity on confrontation. However political changes in Europe required a new look at the pan-European project, its goals, objectives, and principles of integration. The signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and the fundamental decision of the Copenhagen summit in June 1993 to allow Central and Eastern European countries to join the European Union prodded the EU into taking more meaningful and purposeful efforts to form European identity as an important element of its political and value space. The main reason for those efforts was the changing external environment and growing heterogeneity within the Union.

Forming the EU’s identity is an attempt to combine the national and supranational identity of EU citizens, avoiding contraposition and co-subordination but emphasizing important uniting elements of identities. Apart from the idea of minimal interference of EU institutions in the work of national governments, the EU also worked to develop the legal framework for common citizenship. In 2000, the EU summit in Nice adopted the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which was included in the Treaty of Lisbon of 2007. Attempts to create a single supranational legal framework for relations between EU citizens and EU institutions can be interpreted as efforts to build a civic nation and matching EU identity.

In the 1990s and the 2000s, EU institutions worked to create an active field for symbolic interaction between European citizens and popularize and disseminate knowledge about the EU’s concrete positive actions which affect the life of people in Europe (cognitive-emotional aspects of identity). One of the examples is the popularization of the common European symbols such as the flag and anthem of Europe. The introduction of a single currency, the euro, in 2002 became a consolidating symbol used by Europeans in their everyday life. Concrete forms of symbolic interaction between EU citizens and institutions also include the Schengen area of visa-free travel, the uniform health record and driver’s license, the Bologna Process and special EU-funded programs to preserve cultural heritage, museums, and student mobility, and develop science. Special attention is paid to courses studying the history of the EU and its current situation, which are implemented through the Tempus, Jean Monnet, Erasmus+ and other projects.

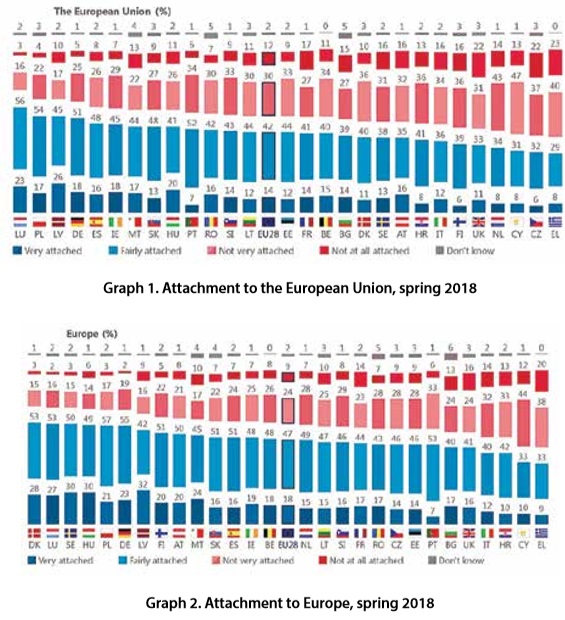

A Eurobarometer survey conducted in the spring of 2018 shows a stable tendency among EU citizens to preserve their national or local identity and a less manifest supranational identity. According to the survey, 93% of respondents said they feel attached to their “country”; 89% feel attached to their “city/town/village”; 65% feel attached to “Europe”; and 56% feel attached to the “European Union” (Standard Eurobarometer 89). The same survey shows that in some EU countries the feeling of belonging to the EU divides, rather than unites society. Low levels of the sense of EU citizenship are seen in Greece (51% said they feel they like EU citizens vs 49% who said they do not), the United Kingdom (57% vs 41%), Italy (56% vs 43%), the Czech Republic (59% vs 40%), and Bulgaria (51% vs 46%) (p. 32). The analysis of people’s attachment to the EU or Europe shows that a majority of respondents in EU countries feel attached to Europe, rather than the EU. A majority of the population feel attached to the EU only in 20 of the 28 EU countries, while a majority of people feel attached to Europe in 26 countries. Below are diagrams illustrating these data (Standard Eurobarometer, 2018: 14, 16).

A 2014 survey requested by the European Commission and called “The Promise of the EU” shows similar results. The respondents most highly valued the EU’s achievements in economic integration and free movement of people. Among negative aspects of EU membership, people named “too many regulations, with the EU being seen as inefficient and interfering with things that should be regulated at the national level,” “the inability to restrict the import of low quality goods, resulting in more products of poor quality coming into the country,” and “concerns, especially among Eurosceptics, that open borders will lead to citizens of other countries coming and taking jobs, or taking advantage of high social benefits without ever having the intention to contribute to local society.” On the whole, most respondents were of the opinion that “the benefits of the EU outweigh the negative aspects” (The Promise of the EU, 2014: 4-5).

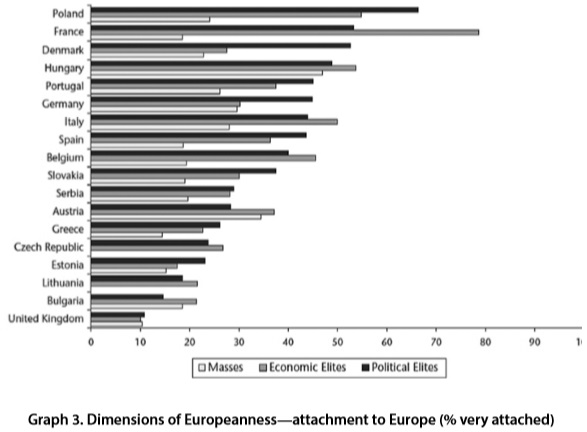

European identity was also the focus of a large research project implemented in 2005–2009 and titled IntUne (Integrated and United. The Quest for Citizenship in an Ever Closer Europe). The survey used quantitative and qualitative methods and comprises monographs examining the sense of European identity in four dimensions: political and economic elites, masses, and the media. Below is a diagram illustrating different degrees of attachment to Europe in EU countries at the levels of people and political and economic elites (Best et al, 2012: 210). The diagram shows that European identity was poorly represented at the level of society in all EU countries, compared with a clearly expressed supranational identity among political and economic elites. In some countries, the overall level of European identity was critically low—the United Kingdom, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Estonia, the Czech Republic, and Greece.

Economic elites generally supported deeper integration and broader powers for supranational bodies to remove barriers in the economic sphere, but they objected to common tax and social security systems. Political elites showed an ambivalent attitude, but their ambivalence was slightly different. They used the idea of ??European integration to win public support during elections in their countries, but in the decision-making process at the European level they were more interested in maintaining an interstate approach and a high role of national governments in solving pan-European problems. Political elites sought to retain competencies in areas affecting the population’s standard of living, namely, taxation and social security. On the contrary, the population of EU countries showed great interest in harmonizing tax and social security systems and creating a single supranational area (Best et al, 2012).

The analysis of the press and TV programs shows that the image of Europe is still very vague and interpreted arbitrarily as some geographic area or the EU. Interestingly, it was more typical of French television, for example, to speak of a “common pan-European identity” with a strongly pronounced concept of “collective we” concentrated around France. In the UK, on the contrary, Europe was often depicted skeptically as something detached. A comparison of the British and Italian press shows that in Italy common European history mostly depicts postwar developments, whereas in the UK it covers a much larger span of time, including the history of European colonialism and empires (European identity, 2012).

To sum up, for Europeans living in EU countries, European identity and EU identity are different categories, while supranational identity remains secondary to national and local identity. Britain’s exit from the EU as a result of the 2016 referendum confirms the validity of the results of opinion polls in European countries. One can even say that the formation of a political nation in the EU is still a process, rather than an accomplished fact, and that EU identity does not replace European identity, as the feeling of non-political attachment, for EU citizens.

RUSSIANS’ ATTITUDES TO THE EUROPEAN UNION AND EUROPE

The analysis of Russian people’s attitudes to Europe shows that the feeling of European identity stemmed from the nature of relations between the EU and Russia (Semenenko, 2013: 103). In the early 2000s, many Russians thought it was possible for Russia to join the European Union and believed that this would be in the country’s economic and political interests. Opinion polls conducted by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM) on the eve of the EU’s eastward enlargement in 2004 showed that almost an equal number of Russians (30 to 35 percent) supported Russia’s potential accession to the EU or the establishment of partner relations with it. Opponents of Russia’s partnership with the EU numbered 14 to 20 percent. Opinion polls showed that the degree of support for Russia joining the EU depended on respondents’ educational level, and almost 40 percent of respondents with higher education supported this option. The analysis of respondents’ political party affiliation revealed that advocates of integration were largely members of the United Russia party (VTsIOM). Surveys on would-be referendums on EU membership conducted in Russia demonstrated an even greater degree of support for the idea: in 2001, 55% of respondents would have voted for and 21% against; in 2003, 60% would have voted for and 14% against; and the figures for 2004 were 45% for and 30% against (VTsIOM, 2004a).

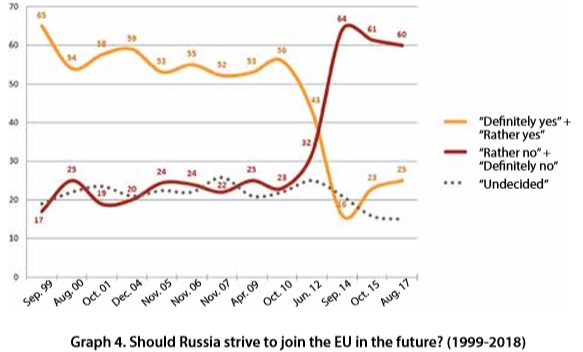

Despite the gradual realization of the impossibility of joining the EU, the majority of Russians maintained a positive attitude to the EU even after the first major crisis in 2008 caused by the August war with Georgia. The full realization of the impossibility of EU membership for Russia (64%) was registered by the Levada Analytical Center in September 2014, whereas in October 2010 the majority of respondents (56%) believed that “Russia should strive to join the EU in the future,” and 23% were opposed to this idea. In 2013, the percentage of supporters and opponents of Russia’s EU membership was almost equal (Levada Center, 2017).

Currently, Russian people’s attitude towards possible admission to the EU is determined by mutual sanctions and growing tension along the country’s western border after the reincorporation of Crimea and the outbreak of the ongoing military conflict in the east of Ukraine. Most Russians understand that there is no way for their country to be admitted to the EU, but there has been a slight decrease in the number of those who thought that “Russia should not seek to join the EU” in the past three years and a considerable increase in the number of those who thought otherwise. On the whole, the graph above reflects diametrically opposite changes in the attitude of Russian people.

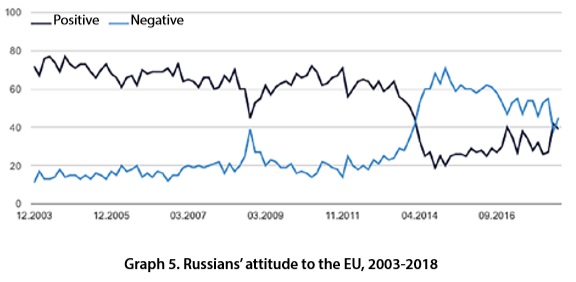

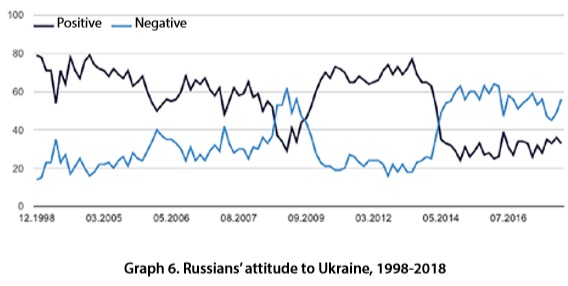

Levada Center surveys on Russians’ attitudes to the EU illustrate all crisis points and the turnabout in them in the period from 2003 to 2014. In September 2018, 39 percent of respondents had a positive attitude to the EU and 45 percent were negative. Graph 5 is surprisingly similar to Graph 6 illustrating Russians’ attitudes to Ukraine (Levada Center, 2014).

The state of Russia-EU relations obviously influences the perception by Russians of their country as European. In December 2008, 56% of respondents believed that Russia was a European country, against 32% of those who did not agree with this statement. In September 2009, the ratio changed to 47% vs 36%; in October 2015 to 32% vs 59%; and in August 2017 to 44% vs. 48% (Levada Center, 2017).

Qualitative surveys of the attitude of Russia’s political elite to the EU policy of “Europeanizing and normalizing” their country revealed a generally negative attitude. The EU policy came into conflict with the sense of Russia’s “greatness” and was viewed as inappropriate and unacceptable to Russia (Kratochvil, 2008: 417). Mass opinion polls and qualitative surveys show that Russians have preserved the sense of their country’s greatness throughout the years.

Events that affected Russian people’s attitude towards the EU include the war in Georgia in August 2008 and the normalization of relations after it. The most dramatic changes occurred in late 2013 and early 2014 due to events in Ukraine, the reincorporation of Crimea into Russia, and a series of mutual sanctions between the EU and Russia in the spring and summer of 2014. Unlike Ukraine, until 2013 Russians were not inclined to blame the EU for deteriorating relations in the post-Soviet space. Russian people’s attitude towards the EU slightly worsened after the latter’s eastward enlargement in 2004 and has never returned to its all-time high registered in the late 1990s and the early 2000s.

Russian people’s attitude towards Ukraine has gone through a large number of crises and conflicts for different reasons: problems with the transportation of natural gas to Europe via Ukraine (gas wars); interpretation of historical Soviet-era events and responsibility for mass crimes committed in Soviet times; the shooting down of a Russian civilian plane over the Black Sea in October 2001; the color revolution in Ukraine in 2004; the start of EU-Ukraine talks on the Association Agreement in 2007; Ukraine’s accession to the Eastern Partnership program in 2009; and the like. Crises in relations between the two countries were exacerbated by Ukraine’s choice in favor of cooperation with the EU at a time when its relations with Russia were going down. On the whole, Ukraine’s political drift towards integration with the EU marked a cooling of bilateral relations, even though Russian people’s attitude to Ukraine remained generally positive after the crisis of 2008 and until the end of 2013.

A survey of Russian people’s attitude to the EU within the framework of its project implemented in August 2015 showed that a positive image of the EU was prompted by economic cooperation, trade, and scientific and educational exchanges between Russia and the Union. Negative assessments of the EU were based mostly on political relations, especially in the post-Soviet space. Russians described the EU as an “arrogant, aggressive and hypocritical player” with a very bad attitude towards Russia. Russians also expressed the view that the EU was not able to solve its internal problems, that it depended on the United States in technological development, and that it was not an independent and full-fledged international actor (Analysis of the Perception of the EU 2015).

Some researchers interpret negative assessments of the EU as stemming from the psychological feeling of “inferiority” or discrepancy between Russia and an “ideal Europe” (Gudkov, 2015). Olga Gulyaeva writes in her survey that Russia views Europe as “an example of individual freedoms, social norms and values. The EU is an example of economic modernization, economic dynamism and development. At the same time, political relations between the EU and Russia, characterized by antagonisms typical of relations between great powers, create the context of belonging to Europe but not being part of Europe. For Russia, Europe remains attractive and frightening, appealing and repulsive, hostile and inspiring” (Gulyaeva, 2013: 188).

If “Europeanness” is a country’s development trajectory aimed at increasing freedoms, peace and prosperity, then we can say that this idea is still attractive to many Russians. The problem is that for most Russians, the EU is no longer the embodiment of an “ideal Europe” and is not viewed as a partner in moving towards an “ideal Europe.”

PROBLEMS OF EUROPEANIZATION AS AN EMBODIMENT OF “IDEAL EUROPE” IN THE EU FRAMEWORK

The problem with the policy of “Europeanizing” countries that built their relations with the EU in the 1990s-2000s is that this process began with recognition of the sense of symbolic belonging to Europe and the desire to formalize this sense through joining the European Union. The process of Europeanization continued through a planned and large-scale reorganization of the legal and regulatory space of countries that sought to join an “ideal Europe” on the EU principles and foundations. Without denying the significance and importance of these reforms and their value for the development of political and economic institutions in the reformed countries, we should point out at least two features of this cooperation that have led to serious consequences for the EU in the framework of its eastward enlargement, Neighborhood Policy and relations with countries with no prospects for EU membership: 1) unilateral influence and client relations between the EU and candidate or partner countries, rather than relations based on mutual consideration of interests; and 2) largely technocratic reform with active involvement of political and economic elites and passivity or complete non-involvement of the population of the reformed countries in these processes.

The population of EU candidate and partner countries mainly acted as a legitimizing force, approving the choice of political elites in favor of rapprochement with the EU through public opinion polls or referendums. As a result, after the EU’s eastward enlargements in 2004, 2007 and 2013, differences in goals, content and methods of achieving unity of European countries within the EU entered into a clear conflict both at the level of national policies of individual countries and within the EU between “old” and “new” members. The conflict was aggravated by the deepening European integration in the sphere of monetary relations and the realization of four freedoms governing the movement of capital, services, goods, and people in market conditions and in the aftermath of the economic crisis of 2008-2012. Another obvious effect of the “ideal Europe” project in the EU-15 format was the aggravation of conflicts over the principles and substance of European unity and a clash between different narratives about wartime and postwar Europe and the role of the Soviet Union/Russia in European developments. Since 2014, the EU has been rethinking the goals of European integration and searching for a new unifying idea that would be shared by all EU countries to solve existential crises of the Union (Verhofstadt, 2017).

The EU’s eastward enlargement has created new dividing lines in Europe, although this was not originally intended or planned. The admission of countries of the former Eastern bloc to the EU began to be interpreted as an unequivocal victory of “ideal Europe” over the totalitarian ideology of the Soviet Union and as the EU’s contribution to the destruction of “dividing lines in Europe.” This interpretation of the European integration process inevitably created a symbolic rejection of Russia as the successor to the Soviet Union and strengthened its image of a country that was solely responsible for Soviet-era crimes, whereas other countries of the Eastern bloc and the former USSR began to be regarded as victims of the Soviet regime. This simplified binary interpretation of history could not but add fuel to conflicting narratives about the past and the future of European unity. NATO’s eastward enlargement, which preceded the accession of countries of the former Eastern bloc to the EU, quickly restored the traditional perception of Russia as a potential enemy of the Alliance—largely under the influence of the new NATO members. Frozen or subdued conflicts in the territory of a reforming Europe have become part of the new political configuration and new alliances for settling these conflicts militarily, politically or economically.

The “Europeanization” of Russia undoubtedly has been accomplished in terms of reconciling regulations and activities of public institutions with EU principles and norms. However, practices used by public institutions and relations with the authorities still depend on Russia’s traditions and constitute the well-known problem of “democratic transition” and “authoritarian legacy.” The “normalization” of Russia within the framework of the new system of international relations in Europe has proved to be unsuccessful, because political elites and society in Russia and beyond view their country as a “great power” seeking to preserve and reproduce all elements of its “greatness.” The use by Russia of military force to resolve conflicts, the strengthening of the “vertical of power,” the weakening of civil society institutions, and the curtailment of international cooperation has led to its universal rejection by Europeans as not being a “normal European country” (Averre, 2009; Haukkala, 2015; Headley, 2012; Tumanov et al., 2011). According to Richard Sakwa, the EU’s attempts to “normalize” Russia can be compared to solving the German problem in the twentieth century within the frameworks of the European integration project (Sakwa, 2015); however, in the ironic phrase of Stephen Kotkin, “Germany and Japan had their exceptionalism bombed out of them. Russia’s is remarkably resilient” (Kotkin 2016). Modern Russia is often opposed to liberal Europe and denied belonging to this “ideal community” (Laruelle, 2016).

The deterioration of Russia-EU relations increases anti-European sentiment in the Russian expert community in favor of building up the country’s military potential, ensuring its sovereignty as a guarantee of its security, and looking for other partners for economic development (Karaganov, 2018). The suspension of the Russian delegation’s work in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 2014 was followed by Russia’s decision to stop paying its Council of Europe membership fee in 2016. In addition, in 2018, Moscow threatened to withdraw from this organization and the European Court of Human Rights. These developments increase the tendency towards Russia’s withdrawal not only from symbolic but also political and organizational circles of European communities. At the same time, Russian experts and society realize the importance of the country’s European identity and the need to improve relations with EU countries even without its deep integration with them. Moreover, the success of the Eurasian integration project is considered in conjunction with the need to strengthen Russia’s European identity (Kortunov, 2018).

* * *

The transformation of Europe after the end of the Cold War began with an awareness that all countries wanted to see an ideal, peaceful and prosperous Europe without dividing lines. However, it ended with a reconfiguration of military and political alliances with clear-cut boundaries, prospects for development, and reassessment of allies and potential adversaries. The “Europeanization” policy, as harmonization with EU norms and principles, inevitably gave rise to conflicts in and between the reformed countries over which narrative of the past and future of Europe is decisive and what countries are “European.” The transformation of Europe has come a long way from recognition of a symbolic community of different countries as the basis for rapprochement, to the reform of the European political space, to a symbolic demarcation due to the emergence of a new military-political balance of power. On one side of the demarcation line are EU members and countries that would like to join the EU, and on the other side, the Russian Federation, well-aware of its problems and conflicts. A recent report of an EU-Russia expert group says that, despite different assessments of the causes and nature of conflicts between the EU and Russia, dialogue between them is necessary and possible in order to find joint ways to restore European unity on new grounds, and that they should jointly look for the formula of an “ideal Europe,” which may not be limited to the EU only (Fisher and Timofeev, 2018).

References

Accession criteria, 2018. EUR-Lex [online]. Available at: <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/glossary/accession_criteria_copenhague.html> (Accessed 28 November 2018)

Averre, D., 2009. Competing rationalities: Russia, the EU and the ‘Shared Neighbourhood’. Europe-Asia Studies, 61, No. 10, pp. 689–713.

Best, H., 2012. Elite-population gap in the formation of political identities. A cross-cultural investigation. In: Gaman-Golutvina, O. and Klemeshev A., eds. Political elites in new and old democracies. Kaliningrad: Baltic Federal University Press, pp. 304-317.

Best, H., Lengyel, G. and Verzichelli, L., eds, 2012. The Europe of elite. A study into the Europeanness of Europe’s political and economic elites. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eder, K., 2006. Europe’s borders: the narrative construction of the boundaries of Europe. European Journal of Social Theory, No. 2, pp. 255-271.

Chapters, 2016. Chapters of the acquis. European Commission. European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations. [online]. Available at: <https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/policy/conditions-membership/chapters-of-the-acquis_en> (Accessed 28 November 2018).

Fisher, Z. and Timofeev, I., 2018. Vyborochnoye sotrudnichestvo mezhdu YeS I Rossiyei. Promezhutochny doklad [Selective cooperation between the EU and Russia. A preliminary report]. EUREN. RSMD, October.

Gudkov, L.D., 2015. Rossiya’ne razlyubili Yevropu. Kak antizapadny razvorot rossiskoy politiki povliyalna massovoye soznanie [Russians have fallen out of love with Europe. How the anti-Western turn changed mass consciousness]. Novaya Gazeta, 4 December.

Gulyaeva, O., 2013. Russian vision of the EU in its interactions with the neighbourhood. Baltic Journal of European Studies, 3, No. 3(15), pp. 175-194. DOI: 10.2478/bjes-2013-0026

Haukkala, H., 2015. From cooperative to contested Europe? The conflict in Ukraine as a culmination of a long-term crisis in EU–Russia relations. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 22, No. 1, pp. 25–40.

Headley, J., 2012. Is Russia out of step with European norms? Assessing Russia’s relationship to European identity, values and norms through the issue of self-determination. Europe-Asia Studies, 64, No. 3, pp. 427-447.

Isiksel, Turkuler, 2018. Square peg, round hole: Why the EU can’t fix identity politics. In: Benjamin Martill and Uta Staiger, eds. Brexit and Beyond: Rethinking the Future of Europe. UCL Press.

Karaganov, S.A., 2018. My ischerpali yevropeiskuyu kladovuyu [We have exhausted the European stockroom]. Ogonyok, No. 34, 10 September.

Kockel, Ullrich, 2010. Re-visioning Europe frontiers, place identities and journeys in debatable lands. Palgrave.

Kortunov, A.V., 2018. Vernyotsa li Rossiya v Yevropu? [Will Russia return to Europe?] RSDM. Analiticheskie Stat’yi, 17 August.

Kotkin, S., 2016. Russia’s perpetual geopolitics. Putin returns to the historical pattern. Foreign Affairs, May/June.

Kratochvíl, P., 2008. The discursive resistance to EU-enticement: the Russian elite and (the lack of) Europeanisation. Europe-Asia Studies, 60, No. 3, pp. 397-422.

Laruelle, Marlene, 2016. Russia as an anti-liberal European civilization. In: Pål Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud. eds. The new Russian nationalism: imperialism, ethnicity and authoritarianism 2000–2015. Macmillan: Edinburgh University Press.

Levada Center, 2017. Rossiya i Yevrosoyuz. [Russia and the European Union]. Levada Center, 19 September, [online]. https://www.levada.ru/2017/09/19/16628/

Levada Center, 2018. Indikatory. Otnosheniya k stranam [Indicators. Attitudes to various countries]. Levada Center, [online]. https://www.levada.ru/indikatory/otnoshenie-k-stranam/

Marquand, J., 2009. Development aid in Russia: lessons from Siberia. London: Palgrave.

Sakwa, R., 2015. The Ukraine crisis and the crisis of Europe. Sibirskie Istoricheskie Issledovaniya, No. 3, pp. 8-39.

Semenenko, I., 2013. The quest for identity. Russian public opinion on Europe and the European Union and the national identity agenda. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 14, No.1, pp. 102-122.

Standard Eurobarometer, 2018. Standard Eurobarometer 89. European citizenship. March. Published June 2018.

The Promise of the EU, 2014. The Promise of the EU: Qualitative Survey: Aggregate Report. (September).

Treaty of European Union, 1992. Available at: https://europa.eu/european-union/sites/europaeu/files/docs/body/treaty_on_european_union_en.pdf

Tumanov, S., Gasparishvilii,A. and Romanova E., 2011. Russia–EU relations, or how the Russians really view the EU. Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 27, No. 1, pp. 120–141.

Verhofstadt, G., 2017. Europe’s last chance: Why the European states must form a more perfect union. Basic Books.

VTsIOM, 2004a. Press vypusk 70. Rossiya-Yevropa: v predverii sammita v Irlandii. [Press release 70. Russia-Europe: in the run-up to the summit in Ireland]. VTsIOM, 24 March. https://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=3357

VTsIOM, 2004b. Press vypusk 76. Yedinaya Rossiya stremitsya v Yevropu. [Press release 76. Yedinaya Rossiya stremitsya v Yevropu. [Press release 76. united Russia party craves for europe]. VTsIOM, 26 april. https://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=3405