For citation, please use:

Luchina, M.S., 2025. Russia and China in the Great Strategic Triangle. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(4), pp. 118–133. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-4-118-133

The current configuration of international relations, though presumably still in the making, is often called polycentric. But in the nuclear balance of power, three centers are easily distinguished: Russia, China, and the United States. The nuclear factor’s growing importance[1] for each, and for relations between them, justifies the analysis of their interactions within the model of a triangle.

This model has proven helpful in analyzing interdependent trilateral relationships, and become popular among researchers due to Kissinger’s successful exploitation of the USSR-USA-China triangle, drawing closer to Beijing while splitting it from Moscow, thus weakening the latter.

Lowell Dittmer’s classic text proposes four types of interaction within a triangle: unit veto (enmity among all three actors), stable marriage (two versus one), romantic triangle (one on cooperative terms with the other two, which are mutually hostile), and the ménage à trois (all cooperate with each other) (Dittmer, 1981, p. 489).

Modern Russian IR researchers have extensively studied this analytical model. Alexandra Khudaykulova, emphasizing the military dimension of triangular relations, has noted the interdependence of their participants’ security (Khudaykulova, 2020, p. 56). This interdependence was examined in detail by Alexei Arbatov and Vladimir Dvorkin in The Great Strategic Triangle (2013), in which they analyzed strategic relations between Russia, China, and the U.S. (The authors followed U.S. nuclear policy experts of the 1950s-1960s in referring to issues of nuclear weapons as ‘strategic.’)

Arbatov and Dvorkin’s conclusions and the Great Strategic Triangle (GST) model provide the main theoretical framework for this analysis of U.S.-Russia-China relations in the realm of strategic arms.

This analysis proceeds from the following assumptions:

- Nuclear issues are the most important, but not the only, factor affecting triangular relationships.

- There is not one dyad, as in the Cold War, but three (two channels emanating from each node) (Bogdanov, 2024, p. 10).

- Moscow, Beijing, and Washington are completely independent vertices of the triangle. They are fully sovereign, and not bound (by collective security commitments or otherwise) to strictly coordinate policy, although cooperation is not excluded.

- There is “rough equivalence between the three [countries], at least to the extent that each can realistically aspire to influence the behavior of the other two” (Bobo, 2010).

Bobo emphasized the latter point in his criticism of the applicability of a strategic triangle model to U.S.-Russia-China relations, both in the nuclear context and more generally. However, given the changes in international relations over the past fifteen years, his idea needs adjustment.

Bobo argued that the U.S.-Russia-China triangle was irrelevant to the U.S. as the sole superpower. Russia, seeking a greater role in international relations, was still not on an equal footing with the U.S. And China was uninterested in confronting the U.S. or in aligning with Russia to the detriment of its relations with Washington (Bobo, 2010). So, there could simply be no triangle in the early 2010s, because of mismatching capabilities.

However, more than ten years on, this argument obviously no longer reflects reality, due to the erosion of American dominance[2] and due to the acquisition by Russia and China of new assets from the Crimean Spring, the Special Military Operation, and the Belt and Road Initiative. These acquisitions allow Russia and China to more effectively project their own influence and oppose the U.S. This opposition is most vivid in China’s global economic projects and in Russia’s military-political activity in various regions of the world. Both weaken America’s ‘rules-based order.’

Bobo attached relatively little importance to the nuclear dimension of the U.S.-Russia-China triangle, given the significant inferiority of China’s arsenal (only 35-40 intercontinental ballistic missiles) at the time (Bobo, 2010). However, Beijing has been rapidly overcoming this imbalance. Chinese missiles capable of reaching CONUS[3] now number about 135 (Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2024). So, the three parties are gradually becoming roughly equal, which actualizes the question of interdependence between them, and its analysis through the triangular model.

Each dyad of the GST has its own specific characteristics. The Russian-American one is characterized by nuclear deterrence based on recognition of mutual assured destruction (MAD), nuclear parity, and a long experience of nuclear arms limitation and reduction talks. The Sino-American dyad is also affected by deterrence, but lacks such basic elements as nuclear-missile parity, recognition of MAD[4] (regardless of the reality), and arms control dialog.

More than ten years ago, Russian experts acknowledged the possible existence of latent deterrence between Russia and China (Arbatov and Dvorkin, 2013). This was produced by the ability of the states’ strategic capabilities to be immediately retargeted (including at each other) if the geopolitical situation were to change. In addition, Moscow and Beijing did not have any strategic agreements, and had already once experienced a drastic downturn in mutual perceptions during the Cold War. Experts also considered China’s intermediate and shorter-range missile capabilities, and Russia’s difficulties in hypothetically defending its border with China (Kashin, 2013). However, given the constructive development of relations between Russia and China since the early 2010s, and the conflict of both (albeit to different degrees) with the U.S., the question of deterrence between them is purely hypothetical and largely retrospective.

Russia and China form the triangle’s base, which is in a state of de facto mutual deterrence with the U.S at the triangle’s apex. This structure is unique in the history of nuclear deterrence, which had previously involved only two actors.[5]

THE RUSSIAN-CHINESE BASE OF THE TRIANGLE

In July 2021, China was reported to have started building more than a hundred missile silos and three bases for intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the country’s center (CNN, 2021). The number of launch facilities under construction has since increased to about 350 (Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2025). China has also recently tested a hypersonic glide vehicle with a range of 40,000 km, seen by American experts as designed for a decapitation strike (America’s Strategic Posture, 2023). All this suggests that the policy of minimal deterrence is losing relevance for Beijing, which is strengthening its nuclear capabilities, estimated by the Pentagon’s at 600 warheads in 2024 (U.S. DoD, 2024).[6]

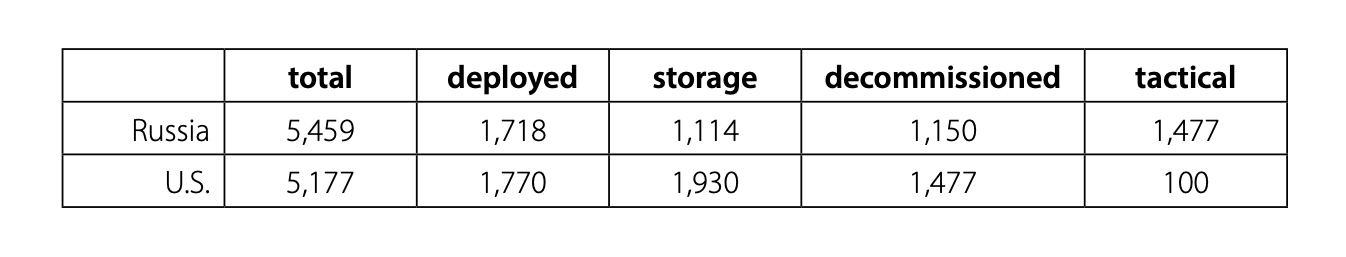

Reports predict that China will increase its arsenal to about 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030 (TASS, 2021) and to about 1,500 by 2035 (Reuters, 2021). For comparison: As of September 2022 and March 2023, Russia and the U.S. had 1,549 and 1,419 deployed warheads, respectively, per START counting rules (Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2024; U.S. Nuclear Weapons, 2024). By 2025, the situation was as follows:

Why is China augmenting its arsenal so rapidly?

The basic tenets of China’s nuclear doctrine have traditionally included the no-first-use posture (Ministry of National Defense, 2023), minimum nuclear capabilities (Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2024), and first-strike uncertainty,[7] i.e., a situation in which the enemy cannot be certain about the success of a disarming strike (Riqiang, 2020, p. 85). Such a doctrine has advantages and disadvantages.

Minimizing nuclear capabilities also minimizes the burden on the national budget, and it creates a positive image of China as a great power that is not seeking an arms race.

However, one disadvantage of China’s traditional approach is the possible insufficiency of its arsenal, now that other countries are rapidly building up their own (USCC, 2021). Moreover, first-strike uncertainty inherently makes for uncertain retaliation (Riqiang, 2020, p. 114), as there is a risk that the enemy’s first strike will prevent retaliation.[8] This may prompt an adversary to develop its counterforce capabilities by increasing the accuracy and penetration of its weapons, as well as to improve and enlarge its missile defense in order to minimize China’s potential for retaliation.

China’s nuclear weapon buildup is aimed at eliminating this vulnerability. It may also be intended to convince the U.S. that MAD exists between the two states. (To do this, Beijing does not need to achieve parity like that sought by the USSR in the Cold War; strategic thought has evolved beyond rigidly conditioning MAD upon numerical parity in strategic weapons.) Recognition of MAD may prompt the parties to launch arms control negotiations for the Pacific region. Although the outlines of possible agreements are still difficult to imagine, just the recognition of MAD could impose a logic of interaction that, like the one between the U.S. and USSR, facilitates the gradual limitation and reduction of arms.

Additionally, China’s strategic buildup may strengthen its position regarding Taiwan and the territorial disputes with Japan and the Philippines, deterring the U.S. from direct military intervention in a crisis (USCC, 2021).

The two countries’ history of cooperation since the Cold War and their similar security challenges provide the prerequisites for their formation of a common base within the GST, one that features close military cooperation without the prospect of an actual alliance. (The parties wish to avoid excessive interdependence and overcommitment to each other’s individual problems.)

Russian-Chinese cooperation is further strengthened by their mutual desire, after the Cold War, to reduce tension in the world and specifically in the center of Eurasia, to resist growing American hegemonism, and to promote a polycentric world order (RG, 2021). These goals led to the creation in 2001 of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the conclusion in 2001 of the Sino-Russian Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation, and the resolution in the 2000s of the two countries’ remaining territorial disagreements. Although these initiatives did not concern strategic weapons directly, they nevertheless affected the GST’s dynamics, aligning Russia and China regarding a number of military-political issues and regarding the world order that should replace the ‘rules-based order.’

This has led to careful cooperation on deterrence issues. For example, Russia helped China create an early warning system (Kommersant, 2019), which may allow China to shift from a second-strike doctrine to a launch-on-warning doctrine. There was also an agreement signed in 2009 on notification regarding missile and rocket launches.

On the other hand, there are factors that could negatively affect relations between Moscow and Beijing. First, Russia must take into account the fact that “China, using its intercontinental and even medium-range missiles, could strike the main administrative and industrial centers in the European part of Russia, and even the most important missile, naval, and air bases of the Strategic Nuclear Forces” (Arbatov, 2022, p.11). Second, the strengthening of China’s deterrence capabilities may distract Washington from strategic dialog with Russia.

The Kremlin may eventually adopt a more cautious approach to China’s nuclear rise, which may in turn sour relations between the two countries. However, this is unlikely to lead to deliberately scrapping the results achieved through military cooperation, or to the GST’s transformation into a ‘unit veto’ or ‘romantic’ triangle. Especially given the challenge faced by both countries from the U.S.

THE AMERICAN VERTEX

The U.S. is currently upgrading its strategic triad, with new Sentinel ground-based ICBMs, Columbia-class SSBNs, and Raider B-21 bombers to be deployed in the foreseeable future. Such upgrades usually cause tension and aggravate relations between the parties to deterrence.[9]

In addition, “this program was originally intended to meet the START-3 ceilings and those of a possible new agreement with similar parameters. However, the uncertainty arising from START’s [suspension] may push Washington into expanding its planned long-range strategic programs without restrictions” (Arbatov, 2023, p. 10).

This uncertainty may be a pretext, as U.S. doctrines reflect the true reasons for its arms buildup. The American Nuclear Posture Review 2022 said that “by the 2030s, the U.S. will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries” (U.S. DoD, 2022). The following year, a special congressional commission presented a report on strategic issues, which proposed to simultaneously contain Russia and China by building up strategic capabilities to the necessary level (America’s Strategic Posture, 2023). Although the report was criticized[10] and the prospects for its implementation remain unclear, the above documents likely depict the modern strategic landscape as seen by U.S. planners, “who are now forced to take into account at least the possibility that China has chosen the path of achieving parity with the U.S.” (Bogdanov, 2024, p. 8).

Washington’s containment policy towards Beijing is systemic and has been pursued for years. Because of the need to provide security guarantees to U.S. allies in the Asia-Pacific, the policy relies significantly on shorter-range weapons. This explains the U.S.’s withdrawal from the 1987 INF Treaty with Russia, probably driven by the need to counterbalance China’s land-based intermediate and shorter-range missiles.[11] (Regional powers’ capabilities are another factor affecting strategic stability in the Asia-Pacific).

The U.S.’s buildup of intermediate and shorter-range missile capabilities in the Asia-Pacific increases its counterforce potential in a possible conflict with China. Washington is already able to reach any target on China’s eastern coast, while Chinese intermediate and shorter-range missiles cannot similarly threaten the U.S. In the spring of 2024, the U.S. deployed, on the Philippine island of Luzon, Typhon systems armed with Tomahawk missiles (range up to 1,800 km) and SM-6 systems (up to 500 km) (Kommersant, 2024). In December 2024, the U.S. successfully tested its new Dark Eagle Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (TWZ, 2024b). It is not yet clear where it will be stationed, but its declared range of more than 2,775 km (per some estimates, 3,400-4,500 km (TWZ, 2024a)) means that it will be able to reach at least Taiwan and the surrounding waters even if deployed as far away as Guam.

The U.S.’s Patriot and THAAD batteries in South Korea, Patriots and an AN/TPY-2 radar in Japan, THAAD batteries in Guam, and Aegis-armed[12] ships cruising in the Pacific all may weaken China’s conventional capacities and reduce its potential for a retaliatory nuclear strike (Bogdanov et al., 2023). In a 2020 test, a Block IIA SM-3, launched from an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, successfully intercepted an ICBM-T2 (TWZ, 2020).

A similar trend is likely to be seen soon on the Russian-American side of the GST. In principle, deterrence between Russia and the U.S. is based primarily on strategic weapons: each country’s arsenal is too large for counterforce measures to significantly weaken its retaliatory potential. However, the INF Treaty’s termination may provoke a new ‘Euromissile crisis,’ perhaps with the announced 2026 deployment of SM-6, Tomahawk, and apparently Dark Eagle systems in Germany (Whitehouse, 2024). In response, the Kremlin may lift its moratorium on deploying intermediate and shorter-range missiles—most likely the new Oreshnik. [The moratorium was indeed lifted on 4 August 2025—Ed.] However, this will not be an exact repetition of the 1980s crisis, partly because it will involve conventional rather than nuclear weapons.

The deployment of these U.S. systems in Europe would obviously pose a threat to Russia and may cause additional tension between the countries, thus pushing Moscow closer to Beijing (and encouraging Beijing to reciprocate), which is something Washington would like to avoid. Canceling the plans to deploy these weapons in Europe could help to defuse the situation, though this alone would not be enough.

ARMS CONTROL IN THE GST

Tension within the GST can be reduced by establishing communication between its three vertices on strategic arms control. However, three-way communication requires attention to each of the three pairs of participants. Each state must mind the interests and interactions of the other two.

A ‘stable marriage’ requires new negotiation tactics. One is a ‘broken triangle’ with two separate dialogs (U.S.-Russia and U.S.-China) that have “different scopes and methodologies, but should meet basic principles: approximate equality of the parties’ capabilities coupled with an in-depth system of measures to ensure their survivability” (Bogdanov, 2024, p. 13).

The trust and strategic cooperation between Moscow and Beijing are such that strategic arms control between them is unnecessary.[13] However, this also makes each uninterested in involving the other in arms control more generally,[14] reducing the likelihood of trilateral negotiations.

The greatest obstacle to a ‘broken triangle’ would be posed by a Chinese decision to reach the START-3 limit, which is clearly unacceptable for the U.S. Negotiations will be unlikely unless/until China’s arsenal reaches a degree of survivability that allows it to maintain an arsenal below the START-3 limit (Bogdanov, 2024, p. 13).

But a Russian-American dialog is also problematic. The Russian Foreign Ministry’s Security Formula suggests also taking non-nuclear strategic weapons into account in START’s successor, but this will likely be rejected by the U.S. in light of the ‘China threat.’ The U.S. strategic community is urging the development of long-range conventional weapons in order to counter China (RAND, 2024). This may reflect an intent to remain below the nuclear level in the event of war with China; the Americans may interpret China’s no-first-use posture as allowing a high-precision preventive strike to which there will be no nuclear response.

So even if the U.S., Russia, and China are minimally ready to discuss strategic arms control, they will have to deal with a “fabric of the negotiation process” that is more intricate than before (Bogdanov, 2024, p. 10).

* * *

The strategic relationships between the three powers, considered within the framework of the Arbatov-Dvorkin model, largely shape the contours of the contemporary strategic landscape, which is in a ‘stable marriage’ between Russia and China versus the U.S. Despite the challenges posed by China’s desire to strengthen its nuclear capabilities, the GST will retain its current configuration until U.S.-Russia and U.S.-China contradictions are resolved. The configuration’s main consequence is a strategic arms race that differs from its Cold War predecessor and means that:

- China will continue its strategic buildup in a bid to deter the U.S. more effectively and strengthen its own position in strategic dialog with Washington. This is already spurring an arms race with the U.S., with Russia likely to join in, too.

- Any strengthening of the U.S. will further boost Russian-Chinese strategic cooperation, thus provoking even greater antagonism between the base of the triangle and its apex.

- The modern strategic arms race will be much more difficult to stop than before, as arms control and compromise are more difficult between three actors. This is one of the 21st century’s main dangers, as it increasingly radicalizes the situation within the Great Strategic Triangle and in the international system as a whole.

[1] Russian experts actively discuss the possibility of using tactical or strategic nuclear weapons in the Ukraine conflict (Karaganov, 2023; Fabrichnikov, 2023; Trenin, 2023). China is enhancing its strategic capabilities, including through the intensive construction of missile silos (CNN, 2021). U.S. doctrine states that “by the 2030s, the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries” (US DoD, 2022).

[2] This is evidenced by U.S. failures in Afghanistan and Iraq, intra-NATO disagreements caused by Washington’s declining willingness to ensure Europe’s security, and the Europeans’ return to the idea of greater defense autonomy.

[3] CONUS (contiguous United States) denotes the continental U.S., including 48 states and the District of Columbia, without Alaska, Hawaii, and the Territories.

[4] Opinions, on the existence of MAD between the U.S. and China, range widely. Some argue that the material conditions for it are absent, as quantitative asymmetry is too great. Others argue that recognition of MAD is politically impossible for the U.S., as this would complicate U.S. relations with allies in the Pacific (Pacforum, 2022).

[5] The Cold War involved the UK and France on the side of the U.S., as well as Chinese capabilities that provoked de facto mutual deterrence between the USSR and China. Yet these peculiarities were peripheral to the U.S.-USSR confrontation.

[6] Due to the lack of official data, and China’s tight control over information on its nuclear arsenal and doctrine, researchers often rely on Pentagon and U.S. intelligence reports.

[7] ’First strike’ is customarily understood as a massive nuclear strike aimed at causing maximum military-strategic damage and making retaliation impossible.

[8] ‘Uncertain retaliation’ can be compared to ‘assured retaliation,’ a retaliatory-strike capability that cannot be thwarted by any counterforce capability, even a decapitation strike. Only Russia and America possess assured retaliation.

[9] For instance, the USSR’s plan in the 1970s-1980s to replace its R-12 and R-14 medium-range ballistic missiles with new ones (of the same Pioneer class), provoked the ‘Euromissile crisis.’

[10] Experts worried that the proposed measures could spark a new arms race, and warned that their implementation could face technical difficulties: “scientists say that previous attempts to deploy mobile ground-based ICBM systems were unsuccessful, and the Air Force Command stated in 2021 that keeping loaded bombers on permanent duty requires too much effort and cannot be sustained indefinitely” (Kommersant, 2023).

[11] “The official reason for the U.S.’s withdrawal from the INF Treaty was that Russia had allegedly been developing and deploying weapons prohibited by the treaty. ‘For far too long, Russia has violated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty with impunity, covertly developing and fielding a prohibited missile system that poses a direct threat to our allies and troops abroad,’ the White House stated, referring to the 9М729 cruise missile. In reality, however, the main reason was China’s growing missile capabilities” (Chekov, 2024, p. 34-35).

[12] The Aegis is a centralized, automated command-and-control (C2) and weapons control system, consisting of an integrated network of sensors and computers, SM-2 and SM-3 interceptors, and the Mark 41 vertical launch system (Topwar, 2012).

[13] Arms control “is relevant when tension is at a certain point, above which it is impossible and beneath which it is unnecessary” (Bull, 1961, p. 75).

[14] Russia and China are focused on the U.S. threat. Furthermore, if one were to encourage the other to participate in negotiations, this might prompt a negative reaction to perceived interference in sovereign affairs.

________________________

America’s Strategic Posture, 2023. America’s Strategic Posture. Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture, October. Available at: https://americanfaith.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Strategic-Posture-Commission-Report.pdf [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Arbatov, A.G., 2022. Стратегическая стабильность и китайский гамбит [Strategic Stability and the Chinese Gambit]. Mirovaya ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 66(3), pp. 5-22. DOI: 10.20542/0131-2227-2022-66-3-5-22.

Arbatov, A.G., 2023. Многосторонний стратегический диалог: дилеммы и препятствия [Multilateral Strategic Dialogue: Dilemmas and Obstacles]. Mirovaya ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 67(7), pp. 5-21. DOI: 10.20542/0131-2227-2023-67-7-5-21.

Arbatov, A.G. and Dvorkin V.Z., 2013. Большой стратегический треугольник [The Great Strategic Triangle]. Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. March. Available at: https://carnegiemoscow.org/2013/03/26/ru-pub-51292 [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Bobo, L., 2010. Россия, Китай и США: Прошлое и будущее стратегического треугольника [Russia, China and the U.S.: The Past and the Future of the Strategic Triangle]. IFRI, 1 February. Available at: https://www.ifri.org/ru/zapiski-ifri/rossiya-kitay-i-ssha-proshloe-i-buduschee-strategicheskogo-treugolnika [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Bogdanov, K., Klimov, V., Krivolapov, V., Stefanovich, L., and Chekov, A., 2023. The Shoot Down/Miss the Target Dilemma: The Evolution of Missile Defense and Its Implications for Arms Control. Valdai Discussion Club, 17 January. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/a/reports/the-shoot-down-miss-the-target-dilemma-/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Bogdanov, K.V., 2024. “Задача трех тел”: “двойное сдерживание»” в политике США и стратегическая стабильность [“The Three-Body Problem”: “Dual Deterrence” in the U.S. Policy and Strategic Stability]. Mirovaya ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, 68(8), pp. 5-16. DOI: 10.20542/0131-2227-2024-68-8-5-16.

Bull, H., 1961. The Control of the Arms Race. Disarmament and Arms Control in the Missile Age. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

Chekov, A.D., 2024. Five Years without the INF Treaty: Lessons and Prospects. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(4), pp. 24-47. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-4-24-47

Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2024. Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2024. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/premium/2024-01/chinese-nuclear-weapons-2024/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2025. Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2025. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/premium/2025-03/chinese-nuclear-weapons-2025/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

CNN, 2021. China Is Building a Sprawling Network of Missile Silos, Satellite Imagery Appears to Show. CNN, 2 July. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/07/02/asia/china-missile-silos-intl-hnk-ml/index.html [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Dittmer, L., 1981. The Strategic Triangle: An Elementary Game-Theoretical Analysis. World Politics, 33(4), pp. 485-515. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2010133

Fabrichnikov, I.S., 2023. Demonstrative Restraint as a Recipe for Unnecessary Decisions. Russia in Global Affairs, 16 June. Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/demonstrative-restraint/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Karaganov, S.A., 2023. A Difficult But Necessary Decision. Russia in Global Affairs, 13 June. Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/a-difficult-but-necessary-decision/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Kashin, V.B., 2013. The Sum Total of All Fears. Russia in Global Affairs, 11(1). Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/the-sum-total-of-all-fears/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Kommersant, 2019. Путин рассказал о содействии Китаю в создании системы предупреждения о ракетном нападении [Putin Spoke of Helping China to Create Early-Warning Radars]. Kommersant, 3 October. Available at: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4112404 [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Kommersant, 2023. Подложили бомбу [They’ve Planted a Bomb]. Kommersant, 13 October. Available at: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6279834 [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Kommersant, 2024. На Азию надвигается Typhon [Typhon Is Impending Asia]. Kommersant, April 16. Available at: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6650107 [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Khudaykulova, A.V., 2020. Геополитические треугольники в контексте конкуренции традиционных и восходящих центров силы [Geopolitical Triangles in the Context of International Security]. Kontury globalnykh transformatsy: politika, ekonomika, pravo, 13(4), pp. 53-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.23932/2542-0240-2020-13-4-3

Ministry of National Defense, 2023. Defense Policy. Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China. Available at: http://eng.mod.gov.cn/xb/DefensePolicy/index.html [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Pacforum, 2022. US-China Mutual Vulnerability: Perspectives on the Debate. Pacforum, May. Available at: https://pacforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Issues-Insights-Vol.-22-SR-2.pdf [Accessed 22 May 2025].

RAND, 2024. Denial Without Disaster — Keeping a U.S.-China Conflict over Taiwan under the Nuclear Threshold. RAND, November. Available at: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA2300/RRA2312-1/RAND_RRA2312-1.pdf [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Reuters, 2021. China Likely to Have 1,500 Nuclear Warheads by 2035: Pentagon. Reuters, 29 November. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china-likely-have-1500-nuclear-warheads-by-2035-pentagon-2022-11-29/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

RG, 2021. Сергей Лавров: Москва и Пекин — сторонники полицентричной системы мироустройства [Sergei Lavrov: Moscow and Beijing Support a Polycentric World Order]. Rossiiskaya gazeta, 16 July. Available at: https:///2021/07/16/sergej-lavrov-moskva-i-pekin-storonniki-policentrichnoj-sistemy-miroustrojstva.html [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Riqiang, W., 2013. Certainty of Uncertainty: Nuclear Strategy with Chinese Characteristics. Journal of Strategic Studies, 36(4), pp. 579-614. DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2013.772510

Riqiang, W., 2020. Living with Uncertainty: Modeling China’s Nuclear Survivability Unavailable. International Security, 44(4), pp. 84-118. DOI:10.1162/isec_a_00376

Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2024. Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2024. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/premium/2024-03/russian-nuclear-weapons-2024/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2025. Russian Nuclear Weapons 2025. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/premium/2025-05/russian-nuclear-weapons-2025/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

TASS, 2021. Пентагон заявил, что КНР способна создать к 2030 году минимум 1 тыс. ядерных боезарядов [The Pentagon Has Stated that the PRC Is Able to Create at Least One Thousand Nuclear Warheads by 2030]. TASS, 3 November. Available at: https://tass.ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/12839925 [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Topwar, 2012. “Иджис” – прямая угроза России [Aegis Is a Direct Threat to Russia]. Topwar, 12 July. Available at: https://topwar.ru/16292-idzhis-pryamaya-ugroza-rossii.html [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Trenin, D.V., 2023. Conflict in Ukraine and Nuclear Weapons. Russia in Global Affairs, 22 June. Available at: https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/ukraine-and-nuclear-weapons/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

TWZ, 2020. The Navy Has Finally Proven It Can Shoot Down an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile. TWZ, 17 November. Available at: https://www.twz.com/37685/the-navy-has-finally-proven-it-can-shoot-down-an-intercontinental-ballistic-missile#comments [Accessed 22 May 2025].

TWZ, 2024a. Hypersonic Weapon Just Tested in Florida, Results Unclear. TWZ, 29 July. Available at: https://www.twz.com/land/hypersonic-weapon-just-tested-in-florida-results-unclear [Accessed 22 May 2025].

TWZ, 2024b. Army’s Dark Eagle Hypersonic Missile Finally Blasts Out of Its Launcher. TWZ, 12 December. Available at: https://www.twz.com/land/army-dark-eagle-hypersonic-missile-finally-blasts-out-of-its-launcher [Accessed 22 May 2025].

U.S. Nuclear Weapons, 2024. United States Nuclear Weapons, 2024. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/premium/2024-05/united-states-nuclear-weapons-2024/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

U.S. Nuclear Weapons, 2025. United States Nuclear Weapons, 2025. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/premium/2025-01/united-states-nuclear-weapons-2025/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].

USCC, 2021. China’s Nuclear Forces: Moving beyond a Minimal Deterrent. USCC, November. Available at: https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/Chapter_3_Section_2—Chinas_Nuclear_Forces_Moving_beyond_a_Minimal_Deterrent.pdf [Accessed 22 May 2025].

U.S. DoD, 2022. National Defense Strategy. U.S. DoD, October. Available at: https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF [Accessed 22 May 2025].

U.S DoD, 2024. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2024. U.S. DoD, December. Available at: https://media.defense.gov/2024/Dec/18/2003615520/-1/-1/0/MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2024.PDF. [Accessed 22 May 2025].

Whitehouse, 2024. Joint Statement from United States and Germany on Long-Range Fires Deployment in Germany. Whitehouse. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/07/10/joint-statement-from-united-states-and-germany-on-long-range-fires-deployment-in-germany/ [Accessed 22 May 2025].