For citation, please use:

Degterev, D.A., 2025. The Sahel Belt: In Search of a ‘Positive Peace’ Formula. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(1), pp. 104–122. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-1-104-122

The terms ‘Sahelian Anomaly’ and ‘Red Belt’ appear increasingly often in newspaper headlines and academic studies regarding the Sahel. Over the past few years, the region has seen military leaders take power, who have united Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger into the Alliance des États du Sahel (AES); first a defense pact and now a confederation. Chad, Togo, and to some extent Senegal tend to cooperate with the AES. However, all these countries face unprecedented security challenges, exacerbated by climate change and deteriorating socio-economic conditions.

Stabilization and lasting, or positive peace are needed here more than ever. Intuitively understandable, “positive peace” was coined by the Norwegian scholar Johan Galtung, for whom it became a lifelong research program, proclaimed in his editorial in the first issue of the Journal of Peace Research (Galtung, 1964). Positive peace implies not only the absence of war, but also the integration of human society, divided by a multitude of conflicts between various groups and not only along national boundaries.

From the analysis of direct or personal violence, Galtung moved to the study of structural or indirect violence, caused by the unequal distribution of resources (Galtung, 1969)—in the spirit of neocolonial center-periphery relations, which he suggested should be overcome through “collective self-reliance” (Degterev, 2024). Finally, Galtung saw the third component of the “triangle of violence” in cultural violence, which includes various aspects of culture, language, art, and science that “justify or legitimize direct or structural violence” (Galtung, 1990, p. 291).

This article is built on these theoretical assumptions, but updated with academic publications from 2022-2024.

The Layer Cake of Sahelistan

A conventional multilevel (local, national, regional, and global) analysis of the Malian crisis (RIAC, 2022, pp. 32-33, 37-40) has already been applied following Paul Williams and his concept of “conflict within conflict” (Williams, 2016, pp. 79-80). However, recent developments prompt a different conceptualization of the situation’s multilevel structure: a “layer cake” of extra-regional actors and their Islamist and separatist proxies (Fituni and Abramova, 2014), which can often swing abruptly from conflict to alliance.

An instance of the latter was displayed on 25-27 July 2024, during a bloody clash in the Tinzaouaten area near Algeria between Russian fighters and the Malian Army versus a hodgepodge of pro-Azawad (Tuareg) separatists and JNIM jihadists (who united around al-Qaeda[1] in 2021) (Davidchuk, Degterev and Sidibe, 2021). Today, these are the two main opposition projects: ethno-nationalist, since 2021 under the CSP-DPA (Cadre stratégique pour la défense du peuple de l’Azawad), and religious, headed by the JNIM (Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin) (Afriyei, 2024, p. 5), which accounts for more than 60% of terrorist attacks in the region and is designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. and the UN (Ibid, p. 2). (Despite this, there are signs of a creeping legitimization of the “moderate jihadists” in the JNIM, whose negotiating strategy has been compared in Western journals to the Taliban’s rise to power (Pieri and Partaw, 2024).)

The layer cake’s final component is Ukraine, the West’s new proxy in Africa (Vedomosti, 2024). Demonstrations of Ukrainian-Tuareg solidarity in the media should not be underestimated, as they reflect the emergence of a stable discursive association between ethnicities purporting to suffer from internal colonization (Bovdunov, 2022).

Meanwhile, Western media are widening their campaign against the AES armies and Russian military advisers, shifting from a focus on the Fulbe and Tuareg peoples to a quasi-global level. This is cultural violence (Galtung, 1990, p. 291). It is no coincidence that the content of the gadgets of the Russians killed at Tinzaouaten has undergone close scrutiny by clearly foreign (likely Western) analysts (AEOW, 2024).

The first layers of the cake were shaped by France as a sub-imperial power that had long seen the region as its neo-colonial fiefdom (pre-carré) (Davidchuk, Degterev and Sidibe, 2022). The Malian authorities assert that the French, aware that control was slipping away from them, sought to destabilize Mali to produce a pretext for their prolonged military presence (Maïga, 2020, pp. 12-17). Operations Serval and Barkhane targeted the Islamists even as the French connived with Azawad separatism. The French helped defeat Islamists in the south, but were in no hurry to assist in reestablishing control over the north. Western experts claim that they were unable to do so. The Malian authorities are certain that they did not want to (Davidchuk, Degterev and Sidibe, 2021, pp. 60-65).

Despite its pretensions to great-power status (most visible in Africa in its numerous military interventions), France has long relied on the logistical, financial, and political support of the collective West. This support is provided through “reluctant multilateralism” (Recchia and Tardy, 2020) within the EU (e.g., training missions and the Takuba Task Force) (RIAC, 2023, pp. 34-36) and within the UN, where France has great influence over peacekeeping and UN policy regarding its former colonies (Adu, Bokeriya, et al. 2023, pp. 421-423).

By the end of 2023, this layer had largely been swept away (Filippov, 2024) by the AES governments with Russia’s support. French expert circles have undergone an acute conceptual crisis and reassessment of policy (Abramova and Degterev, 2024). The U.S. is hardly ready to stand by as its ally loses its sphere of influence to non-Western players, but its attempts to distance itself from Francafrique (especially in Niger) have not been helpful: in August 2024, the U.S. completed the withdrawal of its military from Niger. (As did Germany, which had also tried to distance itself from the French (Trunov, 2024).)

The second tier superficially consists of Islamists: Al-Qaeda (JNIM) and the Islamic State[2] (Davidchuk, Degterev and Sidibe, 2021). Various Islamist groups have long controlled major gold mining areas and promising oil fields. The gold flows from the artisanal miners to the traders (SWISSAID, 2024) and ultimately to the real beneficiaries of the region’s current situation. (Not Paris.)

The region has always been rightly famed for its gold mines. The fortune of Mansa Musa I, the medieval ruler of the Mali Empire, is estimated at $400 billion by modern standards (he was the richest person in the history of the planet) (Warner, 2014). His hajj in 1324-1325—an escort of 60,000 men with so much gold that its price collapsed (Coleman de Graft-Johnson, 2015)—is still legendary. And that was extracted with medieval technology. In the modern day, the crucial role is played by those who supply equipment, pay the workers, and collect the finished products (Raineri, 2020, p. 104). The region is also rich in oil (not yet fully surveyed) and uranium.

Between state actors there are layers of proxies whose actions are not limited by the rules of warfare; their transition to a more official status involves a reputational requirement to provide security in a manner compliant with international law (Loshkaryov and Kopyttsev, 2024, p. 34). The hierarchy of enemies proclaimed by semi-autonomous proxies includes the West, the UN, the infidels, and foreign tourist, with armies and Russian instructors sometimes appearing at the top of it (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 9-10), as has already happened in Syria.

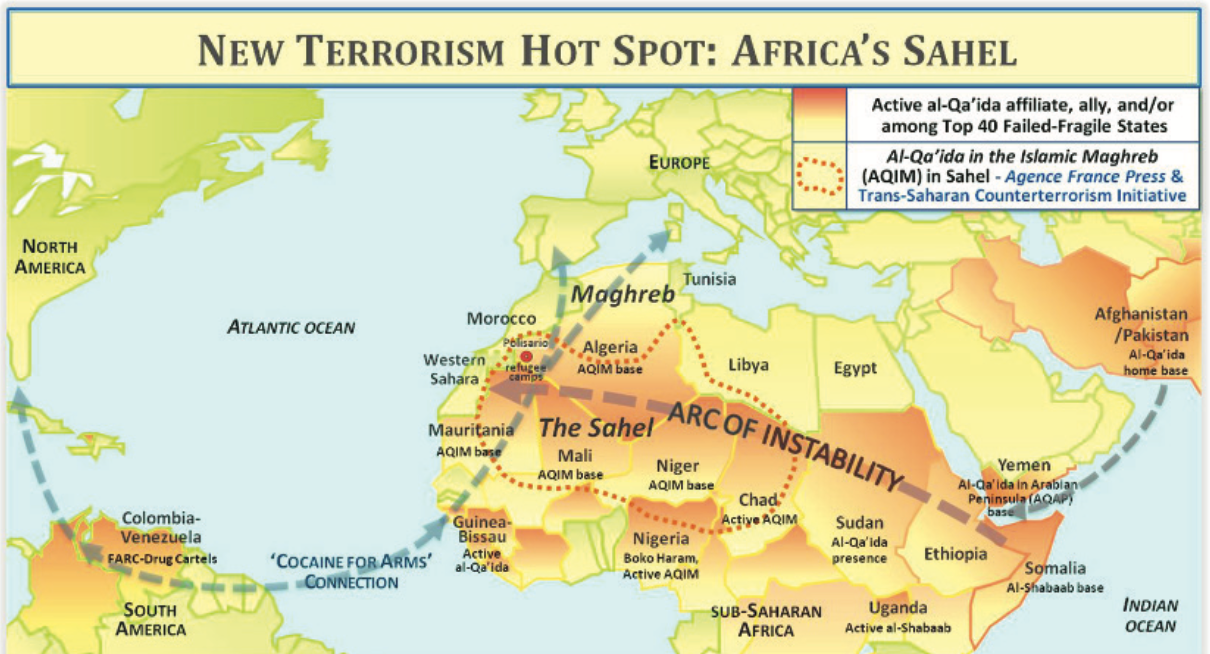

The borders of the “cake” (the dotted line in Fig. 1) were defined back in January 2013 as a self-fulfilling prophecy of the International Center for Terrorism Studies at the U.S.’s Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, almost immediately after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi’s government in Libya and have remained virtually unchanged since then.

Some of the proxies fight for the creation of a Salafi ‘Sahelistan,’ as proclaimed by JNIM leader Iyad Ag Ghali in April 2017 (Afriyie, 2024, p. 5). The abundance of associations with Afghanistan is impressive, not only in terms of the general discourse of failed states (Malejacq and Sandor, 2024), but also in quite tangible terms as depicted by the arrows in Fig. 1. The floating of instability and jihadism is evident (Loshkariov and Kopyttsev, 2024, p. 27) between Afghanistan, the Middle East, and the Sahel working as “communicating vessels” of the “jihadist international”(Semenov, 2024). In a broader context—embracing other African countries—it manifests itself in the ‘Africanistan’ disourse (Michailof, 2018; Hassan, 2020, p. 206).

Fig. 1. Terrorist arc of instability in the Sahel

Source: Alexander, 2013, p. 2.

The fragile Sahel states, critically weakened by IMF/WB structural adjustment programs in the 1980s and the 1990s (Riddell, 1992), find it difficult to resist such threats, which sometimes requires even combined-arms operations with the use of modern artillery and armored vehicles.

Shaping the Economics of the Conflict

After the withdrawal of French, EU, and UN (MINUSMA) troops, Russia began to fill the regional power vacuum and provide security (Loshkariov and Kopyttsev, 2024). But the Sahel needs long-term security arrangements in the military, economic, food, energy, and financial spheres in order to attain comprehensive security and positive peace (Ozerov, 2024).

Regardless of the instability and need for security assistance, which is certainly higher in the Sahel than anywhere else in Africa (Loshkariov and Kopyttsev, 2024, pp. 28-29), Russia needs an exit strategy, since any peacekeeping operation sooner or later reaches a “plateau of international efforts,” and security-providing measures are eventually nationalized (Trunov, 2023, pp. 51-53). Moreover, the timeliness of that nationalization is crucial: delayed sovereignty leads to a negative perception of the security provider, as happened to the West in Mali (Trunov, 2024, p. 162).

Mali’s 25 January 2024 withdrawal from the 2015 Algiers Agreement was an important step towards nationalization. The country’s authorities had been openly critical of this document from the outset. Ex-Prime Minister Choguel Kokalla Maïga has jointly authored a 50-page critical analysis of the Algiers process leading to the 2015 agreement (Maïga and Singaré, 2018, pp. 304-335) and the 2016 agreement on interim administrations (Maïga and Singaré, 2018, pp. 336-351), emphasizing their unfair nature. In a pamphlet—La faillite de l’Etat Malien. Les origines, les responsabilités, les pistes de solutions [The Failure of the Malian State: Origins, Responsibilities, Possible Solutions]—summarizing the ideology of contemporary Mali, Maïga also argues for a gradual revision of the 2015 Algiers Accords (Maïga, 2020, pp. 24-25).

According to Maïga, the internationalization of the conflict with the Tuaregs in northern Mali amounts to unacceptable interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state. It was possible only because the Malian state, as a result of the liberal reforms of the 1990-2000s (under Alpha Oumar Konaré and Amadou Toumani Touré), significantly weakened and essentially betrayed its army. Accordingly, when the Malian army and Russian specialists retook the Tuareg rebel stronghold of Kidal on 14 November 2023, 11 years after it was abandoned, this was a decisive step towards regaining sovereignty. In 2015, French diplomat Michel Dominique Reveyrand, the EU’s special representative for the Sahel, and his office played an important role in organizing and conducting peace talks on Mali. Hence the Algiers Agreement is made largely obsolete by the withdrawal of the EU and MUNISMA (which are mentioned in the Preamble and Articles 18, 21, 51, 56, 58, 60 and 61 of the Agreement (MG, 2015)).

The day after Mali’s withdrawal from the 2015 Algiers agreement, on 26 January 2024, interim President Assimi Goita signed a decree establishing the Steering Committee of the Inter-Mali Dialogue for Peace and National Reconciliation, essentially resuming negotiations with the Tuareg rebels, but from a new position of strength. Yet the bloody events in Tinzaouaten in July 2024 show that Mali cannot really cope on its own with the “coalition of proxies,” and Russian support is still needed. Turkey is also supporting the AES countries with supplies of TB2 attack drones.

Mali is not Russia’s first involvement in a non-Western country’s security provision since its return to a proactive foreign policy: Venezuela, Syria, and the CAR all preceded Mali (Bovdunov, 2023). These cases give reason to consider the distinguishing features of Russia’s approach to peacebuilding, and the means by which it can transition from establishing peace to assisting in post-conflict reconstruction, potentially alongside non-Western partners. Such a transition would usually be accompanied by the transfer of UN responsibility for the crisis from the Department of Peace Operations (since 1997 headed by representatives of France) to the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (since 2016 headed by representatives of the U.S.)[3].

The very term ‘conflict management’ (Kremenyuk, 2003), in contrast to ‘conflict resolution’, semantically seems to imply some procrastination, with states’ systems reformatted and the states drawn into the post-conflict “matrix” of the U.S.-led collective West (Bogdanov, 2023).

In the Sahel there have been attempts to monopolize the control of the illegal economy by the JNIM (Nsaibia, Beevor and Berger, 2023, pp. 33-37, 43), which was established in 2017 on the basis of four major groups:

- Ansar al-Din (predominantly Ardar de Iforas Touaregs from Kidal);

- Katiba Macina (Rimaybe, a sub-ethnic group of former Fulbe slaves);

- Al Mourabitoun (core members of the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), predominantly Arabs and Bella (former Tuareg slaves));

- Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) (predominantly Fulbe and Tuareg) (Davidchuk, Degterev and Sidibe, 2021; Afriyie, 2024, pp. 3-5, 8).

JNIM seized all of the illegal economy’s major sectors, including: kidnapping and drug trafficking (Tilemsi Arabs or Arabs of Gao; Al-Mourabitoun), kidnapping of Westerners, cigarette smuggling (AQIM), cattle raiding, protection racket of artisanal gold mining, road tolling, etc. (Nsaibia, Beevor and Berger, 2023, pp. 10-11). The JNIM in its media advocates “liberalization of the illegal economy” and the demolition of borders, abolition of customs duties, etc. In this it enjoys the support of local smugglers (Ibid, p. 11).

In all cases of protracted conflicts, the absence of legitimate economic institutions does not create an economic vacuum, as a fairly stable conflict economy takes shape.

In fact, the conflict creates neocolonial conditions for the industrial-scale plundering of AES countries—a perfect example of Galtung’s ‘structural violence’ (Galtung, 1990). One should not underestimate the scale and technological resources of artisanal mining. “Capital may be injected by either pit owners themselves, or, more frequently, a ‘logistic provider’, who supplies the means of production, owns the needed equipment and pays for the labor force and its sustenance on the mining site” (Raineri, 2020).

Naturally, the beneficiaries are completely disinterested in changing the status quo, as revealed most clearly by the Malian government’s retaking of Kidal in 2023. Mainstream Western media and Western academic quarters claim that this operation merely “shattered the fragile peace” in northern Mali (Pieri and Partaw, 2024, p. 16). But the plundering of Mali’s natural wealth and future under ‘peace-minded’ Islamists hardly contributes to “positive” peace. Western-centric institutions (Bokeriya and Degterev, 2024) and “liberal peacekeeping” (Karlsrud, 2023) are in crisis. Attempts at “co-operative peacekeeping” in accordance with the Malte Brosig (2015) theory of complex security regimes have failed and given way to forced decoupling (Vasilev, Degterev, and Shaw, 2023). The gap between Western and non-Western security providers is growing wider with gradually increasing tensions (RIAC, 2023). In this context, the need for a non-Western formula for positive peace—be it in Syria, the CAR, Afghanistan, or the Sahel—is more relevant than ever.

Regrettably, regional actors—‘African solutions to African problems’ (Denisova and Kostelyanets, 2023)—have not yet been of much use. The African Union suffers from both internal organizational difficulties (Gottshalk, 2024) and major challenges to its agency, as the organization’s budget in the security sphere relies mostly on EU contributions. The agency of ECOWAS is even more dismal (Adu and Mezyaev, 2023; 2024). At this point, the organization that promotes mainly regional interests is the AES, pursuing a strategy of “collective self-reliance” not only in security, but also in other spheres (Degterev, 2024).

The Vicious Cycle of Tensions: Water Resources

The encompassing of several neighboring countries by security crises testifies to a common, natural origin of their problems. Indeed, however complex the bundle of causes described above may be, the trigger is climate change and water scarcity due to aridization and population growth, although these factors are not given enough credit by international actors or the Sahel governments themselves (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 10-11).

Natural factors (and thus climate change) are extremely important to sedentary farmers and nomadic pastoralists (Grishina, 2024). Drinking water is of particular significance (Mbaye and Signé, 2022, pp. 2-3). Research conducted in Niger in 2015 found that when climatic conditions deteriorate, the Sahelian people first sell their livestock and durable goods, then stop sending their children to school, and finally move elsewhere (Mbaye and Signé, 2022, p. 7). Many refugees abandon villages for cities in ‘false urbanization’, thus joining the ‘precariat.’

Between 1944 and 2020, the average annual air temperature in Burkina Faso and Mali rose from 28.0°C to 29.0°C, and in Niger from 26.7°C to 28.0°C (Mbaye and Signé, 2022, pp. 12-13). The region has also suffered a slight decline in rainfall (Mbaye and Signé, 2022, pp. 9, 11), although the terrible Sahel droughts and famines in 1968-1974 and 1983-1984 have given way to some re-greening (Ibid, p. 9; McGuirk and Nunn, 2024, pp. 7-8). Rainfall is six times more determinative of crop yields than temperature is (McGuirk and Nunn, 2024, p. 8), and most researchers agree that climate instability has been growing, with negative effects on the region’s socio-economic development.

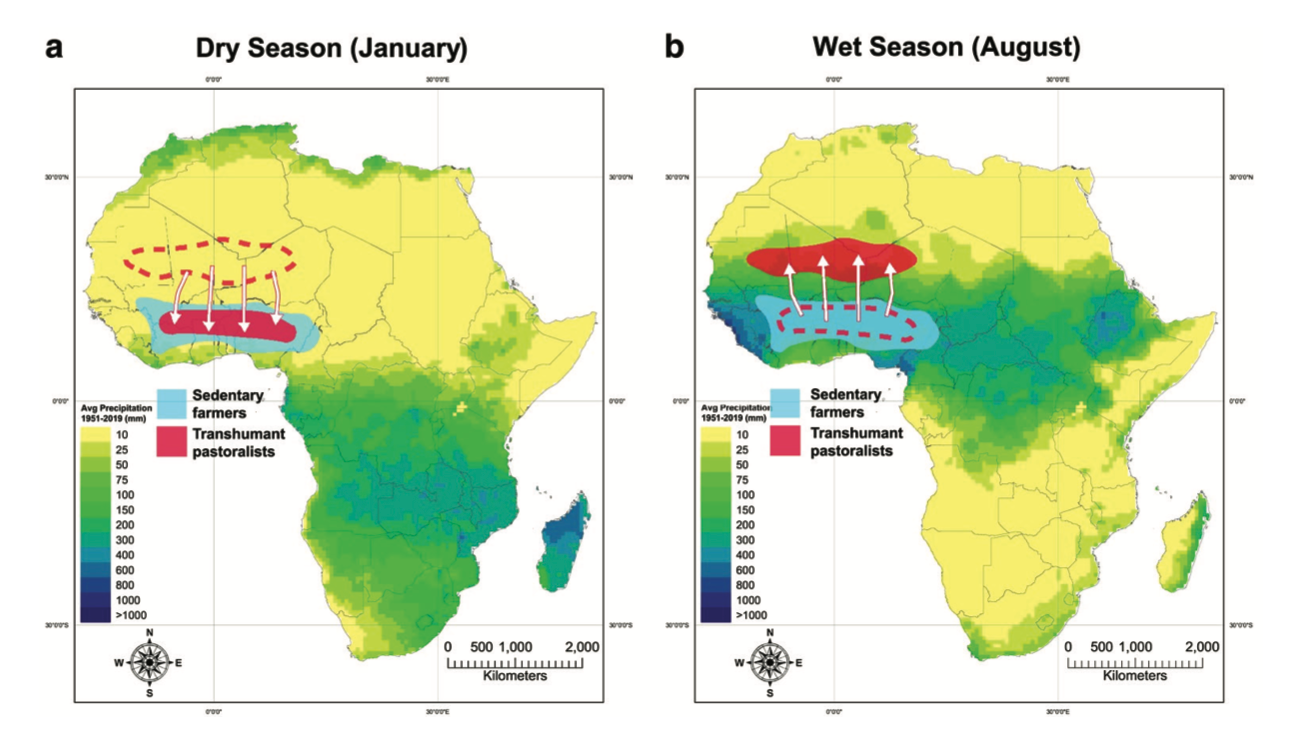

Fig. 2. Seasonal migration in the Sahel

Source: McGuirk and Nunn, 2024, p. 6.

The avoidance of simplistic climate reductionism (Benjaminsen and Ba, 2024, p. 2) requires depoliticized analysis of micro-level processes. The region is host to a natural symbiosis: During the dry season, grass is scarce in the Sahara and pastoralists move their livestock south (see Figure 2a), thus providing organic fertilizer for local farmers. During the wet season, cattle graze in the north, so farmers do not have to worry about their crops (see Fig. 2b).

If a drought causes a shortage of fresh grass in the Sahara, pastoralists move their cattle south before the sedentary farmers have harvested their crops, creating tensions. The different ethnic and religious identities of pastoralists (predominantly Muslim, Fulbe) and farmers (predominantly Christian) permit the exploitation of these tensions by JNIM and others (McGuirk and Nunn, 2024).

The establishment of protected areas actually appears to worsen the situation, as it reduces farmland, blocks some of the corridors for the movement of livestock, and ultimately fuels pastoralist-farmer tensions (McGuirk and Nunn, 2024, pp. 27-31).

More generally, international aid projects (1947-2013) appear to frequently backfire. For instance, the Fulbe people use the burgu cereal for livestock fodder. However, since the 1950s, as a result of the Malian Office Riz Mopti’s operation (financed by the World Bank in the 1970s-1980s and the African Development Bank in the 1990s), burgu crop yields have slumped by a quarter in favor of rice—to the Fulbe people’s great discontent. Well projects launched in the late 1980s by the Office for Livestock Development in the Mopti Region have been heavily criticized by pastoralists, as they have “contributed to increasing land conflicts by drilling new wells in pastoral dryland areas. The new water sources attracted farmers to settle and conflicts over land emerged” (Benjaminsen and Ba, 2024, p. 6).

This sort of thing is what provides fodder for the narratives that stigmatize the state and any efforts made by it at socio-economic development.

The “Positive Peace” Triangle

Galtung noted that peace research “should also be peace search, an audacious application of science in order to generate visions of new worlds” (Galtung, 1964, p. 4). It seems that absolute positive peace is unattainable, a utopia, as recognized by Galtung (1964) himself, so a “pareto optimal” peace may be more attainable (Oh, 2020). Adhering to Galtung’s concepts, let us consider all three components of the “triangle of violence:” direct, structural, and cultural.

The AES’s cognitive sovereignty is crucial for the elimination of cultural violence. The majority of Western popular and academic publications (see, for example, Pieri and Partaw, 2024), with very few exceptions (Afriyie, 2024), negatively portray the actions of the Malian government (the current one, and almost all the others since independence). Meanwhile, the separatists and rebels, including jihadists, enjoy predominantly positive treatment, including with a moral political economy argument (regarding pastoralism!) inspired by critical agrarian studies (Benjaminsen and Ba 2024). Most Western reports on JNIM activities are illustrated not by snapshots of their crimes, but by “romantic” photos of armed jihadists against a backdrop of beautiful sand dunes (Nsaibia, Beevor, and Berger, 2023).

Writing of a true history of the region is a separate field of cognitive battle. The country’s former prime minister, Choguel Maïga, has personally taken part in it with his co-authored 350-page history of all major Tuareg uprisings (Maïga and Singaré, 2018), a kind of response to a Western monograph on the same subject (Lecocq, 2010).

Various socialization tools, both traditional (school, religion, family) and new (social networks, TikTok, podcasts), will play an important role (Degterev, 2022, pp. 359-363). Especially important is primary education, unavailable to a significant share of the AES’s population (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 10-11), and religious education (Bakare, 2016). The government’s provision of basic social services and propagation of a values-based narrative are essential for reducing the social base of the JNIM and CSP-DPA and restoring constructive relations between farmers and pastoralists.

Structural violence can be overcome only through long-term socio-economic development programs (Somé, 2024) that are compatible with Tuareg and Fulbe lifestyles. Large-scale Soviet aid programs (Davidchuk, Degterev and Korendyasov, 2022) might be assessed for effective practices. Russia’s partners from the World Majority, including China, Turkey, Iran, and India, might also be included in socio-economic projects (Karaganov, 2022).

It is of special importance that the AES states restore their sovereignty and law over the extraction of their natural resources (in which they are some of the richest in the world), doing away with neocolonial arrangements such as production-sharing agreements. However, the current Western beneficiaries of these arrangements will prefer to topple AES governments—including with the use of sanctions (Fituni, 2021)—rather than face the loss of profits from mineral extraction in the “forever war.”

As the state gradually builds up its capacity and regains control over territory, anti-government groups must choose between continuing to fight or integrating into the state. Agreements with moderate rebels—e.g., the CAR’s 2019 Khartoum Agreement, brokered with Russian support—are important. But no consideration should be given to ideas of AES governments exhausting their forces against the most serious terrorist groups (e.g., the Islamic State4) and then, weakened, sharing power with the JNIM, which is actually the governments’ most serious competitor (Nsaibia, Beevor, and Berger, 2023, p. 12).

A crucial role is also played by political and military coordination—not only within the AES, enabling effective cross-border counterterrorism operations in the Liptako-Gurma triangle, but also closer cooperation with the two regional leaders, Algeria and Nigeria. (Algeria hosts the African Center for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT) and the African Union’s police cooperation mechanism, AFRIPOL.)

The successful implementation of measures to combat cultural, structural, and direct (military) violence in the AES will contribute to achieving positive peace in the region.

The article is part of the research “The Clean Water Project as a Critical Component of Cooperation between Russia and the Global South Countries: Socio-Economic and Technological Dimensions” done with support from the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Agreement #075-15-2024-546).

[1] Outlawed in Russia.

[2] Both outlawed in Russia.

[3] From 1952 to 1993, the Department of Political and Security Council Affairs, and then the Department of Political Affairs, was headed by representatives of the USSR/Russia. (Adu, Bokeriya, et al., 2023, p. 422; Amara, Degterev, and Egamov, 2022, pp. 84-85).

_________________________

Abramova, E.A. and Degterev, D.A., 2024. “Архитекторы ФрансАфрик”? Экспертно-аналитическое обеспечение современной политики Франции в Африке [“France-Afrique Architects”? Expert and Analytical Support of Frace’s Current Policy in Africa]. Sovremennaya Evropa, 5, pp. 74-87.

Adu, Y.N. and Mezyaev, A.B., 2023. The Conflict Between ECOWAS and Mali: International Legal and Political Aspects. International Organisations Research Journal, 18(1), pp. 170-189.

Adu, Y.N. and Mezyaev, A.B., 2024. Political Turmoil in ECOWAS: When Politics Prevails Over Law. Journal of the Institute for African Studies, 2, pp. 102-117.

Adu, Y.N., Bokeriya, S.A., Degterev, D.A., Mezyaev, A.B. and Shamarov P.V., 2023. Non-Western Peacekeeping as a Factor of a Multipolar World: Outlines of Research Program. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 23(3), pp. 415-434.

AEOW, 2024. (Ordre de) Débandade en Azawad. All Eyes on Wagner, 2 August. Available at: https://alleyesonwagner.org/2024/08/02/ordre-de-debandade-en-azawad/ [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Afriyie, F.A., 2024. Weaving through the Maze of Terrorist Marriages in Africa’s Sahel Region: Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) under Review. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(10), 2347011, pp. 1-13.

Alexander, Y., 2013. Terrorism in North Africa & the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach & Implications. Inter-University Center for Terrorism Studies, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. Available at: https://moroccoonthemove.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/IUCTSTerrorismin2012.pdf [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Amara, D., Degterev, D.A., and Egamov, B.Kh., 2022. “Общие интересы” в миротворческих операциях ООН в Африке: прикладной анализ кадрового состава [“Common Interest” in the UN Peacekeeping Operations in Africa: An Applied Analysis of the Personnel]. National Strategy Issues, 2, pp. 76-101.

Bakare, I.A., 2016. Soft Power as a Means of Fighting International Terrorism: A Case Study of Nigeria’s “Boko Haram”. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 16(2), pp. 285-295.

Benjaminsen, T. and Ba, B., 2024. A Moral Economy of Pastoralists? Understanding the ‘Jihadist’ Insurgency in Mali. Political Geography, 113, 103149, pp. 1-10.

Bogdanov, A.N., 2023. Statebuilding and the Origins of the “American Empire”: Towards the Problem of Legitimizing Sovereign Inequality in the 21st Century. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 23(3), pp. 506-517.

Bokeriya, S.A. and Degterev D.A. (eds), 2024. Миротворчество в многополярном мире [Peacekeeping in a Multipolar World]. Moscow: Aspect Press.

Bovdunov, A.L., 2022. Challenge of “Decolonisation” and Need for a Comprehensive Redefinition of Neocolonialism. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 22(4), pp. 645-658.

Bovdunov, A.L., 2023. OUIS and MINUSCA in the CAR: The Effectiveness of Realist and Liberal Peacekeeping Paradigms. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 23(3), pp. 480-496.

Brosig, M., 2015. Cooperative Peacekeeping in Africa Exploring Regime Complexity. London: Routledge.

Coleman de Graft-Johnson, J., 2015. Mūsā I of Mali. Britannica, 6 August. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170421200707/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Musa-I-of-Mali [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Davidchuk, A.S., Degterev, D.A., and Korendyasov E.N., 2022. Soviet Structural Aid to the Republic of Mali in 1960-1968. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 22 (04), pp. 714-727.

Davidchuk, A.S., Degterev, D.A. and Sidibe, O., 2021. Crisis in Mali: Interrelationship of Major Actors [Vzaimootnosheniya osnovnykh aktorov]. Asia and Africa Today, 12, pp. 47-56.

Davidchuk, A.S., Degterev, D.A., and Sidibe, O., 2022. Военное присутствие Франции в Мали: структурная власть субимперии “коллективного Запада” [France’s Military Presence in Mali: The Structural Power of the Sub-Empire of the ‘Collective West’]. Current Problems of Europe, 4, pp. 50-78. Available at: https://upe-journal.ru/files/_2022_4_%D0%94%D0%B5%D0%B3%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B2_%D0%94%D0%90.pdf [Accessed 2 December 2024].

Degterev, D.A., 2022. Value Sovereignty in the Era of Global Convergent Media. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 22 (02), pp. 352-371.

Degterev, D.A., 2024. Collective Self-Reliance: Restarting the Concept in the Sahel in the Context of a Multipolarizing World Order. Journal of the Institute for African Studies, 2, pp. 60-81.

Denisova, T.S. and Kostelyanets, S.V., 2023. African Solutions to African Problems: Peacekeeping Efforts of the African Union and African Regional Organizations. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 23(3), pp. 451-465.

Filippov, V.R., 2024. ‘Françafrique’ Systemic Crisis. Journal of the Institute for African Studies, 2, pp. 144-156.

Fituni, L. and Abramova, I., 2014. Агрессивные негосударственные участники геостратегического соперничества в “исламской Африке”. [Aggressive Non-State Actors of Geostrategic Rivalry in ‘Islamic Africa’]. Asia and Africa Today, 12, pp. 8-15.

Fituni, L.L. (ed.), 2021. Африка: элиты, санкции, суверенное развитие [Africa: Elites, Sanctions, Sovereign Development]. Moscow: Institute for African Studies.

Galtung, J., 1964. An Editorial. Journal of Peace Research, 01 (01), pp. 1-4.

Galtung, J., 1969. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), pp. 167-191.

Galtung, J., 1990. Cultural Violence. Journal of Peace Research, 27(3), pp. 291-305.

Gottshalk, K., 2024. Six Decades of African Integration: Successes and Failures. Journal of the Institute for African Studies, 2, pp. 24-39.

Grishina, N.V., 2024. Nekotorye aspekty zhivotnovodstva v stranakh Afriki [Some Aspects of Animal Husbandry in Africa]. Journal of the Institute for African Studies, 1, pp. 66-79.

Hassan, H.A., 2020. A New Hotbed for Extremism? Jihadism and Collective Insecurity in the Sahel. Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, 8(2), pp. 203-222.

Karaganov, S.A., 2022. От не-Запада к Мировому большинству [From the Non-West to the World Majority]. Rossiya v globalnoi politike, 20(5), pp. 6-18.

Karlsrud, J. 2023. ‘Pragmatic Peacekeeping’ in Practice: Exit Liberal Peacekeeping, Enter UN Support Missions? Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 17(3), pp. 258-272.

Kremenyuk V.A., 2003. Современный международный конфликт: проблемы управления [Managing Contemprorary International Conflict]. International Trends, 1 (01), pp. 63-73.

Lecocq, J.S., 2010. Disputed Desert Decolonisation, Competing Nationalisms and Tuareg Rebellions in Northern Mali. Leiden: BRILL.

Loshkaryov, I.D. and Kopyttsev, I.S., 2024. Рынок безопасности в Африке: место России и новые возможности [Security Market in Africa: Place for Russia and New Opportunities]. Polis. Political Studies, 4, pp. 23-37.

Maïga, C.K. and Singaré, I.A., 2018. Les rebellions au nord du Mali. Des origines à nos jours. Bamako: Edis.

Maïga, C.K., 2020. La faillite de l’Etat Malien. Les origines, les responsabilités, les pistes de solutions. Bamako.

Malejacq, R. and Sandor, A., 2020. Sahelistan? Military Intervention and Patronage Politics in Afghanistan and Mali. Civil Wars, 22 (04), pp. 543–566.

Mbaye, A.A. and Signé, L., 2022. Climate Change, Development, and Conflict-Fragility Nexus in the Sahel. Working Paper 169. Washington: Brookings Institution.

McGuirk, E.F. and Nunn, N., 2024. Transhumant Pastoralism, Climate Change and Conflict in Africa. Review of Economic Studies, 6 March, pp. 1-38.

MG, 2015. Accord pour la Paix et la Reconciliation au Mali issu du Processus d’Alger. Governement de Mali, Mai et June. Available at: https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/Accord%20pour%20la%20Paix%20et%20la%20R%C3%A9conciliation%20au%20Mali%20-%20Issu%20du%20Processus%20d%27Alger_0.pdf [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Michailof, S., 2018. Africanistan. Development or Jihad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nsaibia, H., Beevor, E. and Berger, F., 2023. Non-State Armed Groups and Ilicit Economies in West Africa. Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JMIN). Issue 1. GI-TOC. ACLED.

Oh, H., 2020. A Pareto Optimal Peace: How the Dayton Peace Agreement Struck a Unique Balance. E-International Relations, 28 June. Available at: https://www.e-ir.info/2020/06/28/a-pareto-optimal-peace-how-the-dayton-peace-agreement-struck-a-unique-balance/ [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Ozerov, O.B., 2024. Интервью Посла по особым поручениям МИД России, руководителя секретариата Форума партнерства Россия-Африка О.Б. Озерова журналу “Новое восточное обозрение” [Interview of the Ambassador-at-Large of the Russian Foreign Ministry, Head of the Secretariat of the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum O.B. Ozerov to the magazine New Eastern Outlook]. NVO, 27 March. Available at: https://mid.ru/ru/ nota-bene/1941275/ [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Pieri, Z.P. and Partaw, A.M., 2024. Learning the Lessons of Afghanistan? The Changing Prospects of Negotiations between JNIM and the Malian Government. Small Wars & Insurgencies, pp. 1-24. DOI: 10.1080/09592318.2024.2380048.

Raineri, L., 2020. Gold Mining in the Sahara-Sahel: The Political Geography of State-Making and Unmaking. The International Spectator, 55(4), pp. 100-117. Available at: https://www.sci-hub.ru/10.1080/03932729.2020.1833475 [Accessed 31 October 2024].

Recchia, S. and Tardy, T., 2020. French Military Operations in Africa: Reluctant Multilateralism. Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), pp. 473-481.

RIAC, 2022. African Pressure Points: Sahel (Situation Review and FuturePprospects). RIAC and ICRC Report No 77. Moscow: Russian International Affairs Council.

RIAC, 2023. Западные и незападные акторы в обеспечении безопасности в Африке [Western and Non-Western Actors in Providing Security in Africa]. Moscow: Russian International Affairs Council.

Riddell, B., 1992. Things Fall Apart Again: Structural Adjustment Programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 30 (01), pp. 53-68.

Semenov, K., 2024. Десять лет террористического “халифата” ИГИЛ [Ten Years of the ISIS Terrorist “Caliphate”]. RIAC, 12 August. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/desyat-let-terroristicheskogo-khalifata-igil/ [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Somé, M., 2024. Главная задача — вернуть народам Сахеля суверенитет [The Main Task Is to Return Sovereignty to the Peoples of the Sahel]. RIAC, 25 April. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/columns/africa/glavnaya-zadacha-vernut-narodam-sakhelya-suverenitet/ [Accessed 5 September 2024].

SWISSAID, 2024. On the Trail of African Gold. Quantifying Production and Trade to Combat IllicitFflows. Bern: Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

Trunov, Ph.O., 2023. Modeling the Country’s Participation in Armed Conflict Resolution: Case of Germany’s Activity in Mali. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 23 (01), pp. 48-66.

Trunov, Ph.O., 2024. Germany’s Strategic Activity in the Sahel and the Problem of Sovereignty for Regional States: The Case of Mali. Journal of the Institute for African Studies, 2, pp. 157-169.

Vasiliev, A.M., Degterev, D.A. and Shaw, T.M., 2023. African Summitry: Representation of “External Other” in the “Power Transit” Era. In: Vasiliev, A.M., Degterev, D.A., Shaw, T.M. (eds.) Africa and the Formation of the New System of International Relations–Vol. II. Beyond Summit Diplomacy: Cooperation with Africa in the Post-pandemic World. Cham: Springer, pp. 1-16.

Vedomosti, 2024. Посла Украины вызвали в МИД Сенегала из-за поддержки террористов в Мали [Ukrainian Ambassador Summoned to Senegalese Foreign Ministry for Supporting Terrorists in Mali]. Vedomosti, 3 August. Available at: https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/news/2024/08/03/1053707-vizvali [Accessed 5 September 2024].

Warner, B., 2014. The Richest People of All Time – Inflation Adjusted. CelebrityNetWorth, 14 April. Available at: https://www.celebritynetworth.com/articles/entertainment-articles/25-richest-people-lived-inflation-adjusted/ [Accessed 5 November 2024].

Williams, P., 2016. War and Conflict in Africa. Malden: Polity Press.