For citation, please use:

Royce, D.P., 2025. The Behavior of Particularistic and Universalistic States. Russia in Global Affairs, 23(1), pp. 70–99. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2025-23-1-70-99

This article proposes a Theory of State Behavior’s Determination by Particularistic/Universalistic Identity-Morality-Ideology. Particularists—states motivated by particularistic identity-morality-ideologies (IMIs), such as civilizationism—are largely free to conduct realpolitik in pursuit of their vital-realpolitik (VR) interests, although they are not guaranteed to do so. (Thus, in practice, some particularists will mostly adhere to realpolitik, while others will display little to none of it.)

But universalists—states motivated by universalistic IMIs, such as Cosmopolitan-Liberalism or Communism—are driven, by the combination of their IMIs and various psychological phenomena, to pursue much more than just their VR interests, via policies far removed from realpolitik. (Thus, in practice, all universalists will engage in negligible realpolitik.)

This causes universalists to impinge upon the VR and non-VR interests of other states far more often than would be necessary to defend the universalists’ own VR interests. Furthermore, short of total accommodation/appeasement, the behavior and nature of other states (even their genuine adherence/conformity to a universalist’s IMI) cannot much mitigate this impingement. These two things leave universalists in draining conflict with other states, and mean that other states have no incentive to get along with or accommodate a universalist, instead aligning with one another and balancing against the universalist.

At present, this is foremost exemplified by the alignment of Russia and China against the U.S., a product of the Cosmopolitan-Liberal U.S.’s continued impingement against both of them, even as their transitions from universalistic Communism to particularistic civilizationism permitted their realpolitik detente and alignment with one another. Indeed, this theory is, to a large extent, intended to explain (and predict) otherwise bizarre U.S. behavior, although the theory’s applicability is much broader.

-

Definitions

1.1. Vital-Realpolitik (VR) Interests of a State

A state’s VR interests consist of:

(1) sovereignty, entailing (1a) the independence of its government, political system, economy, etc. from foreign entities; and (1b) the control/authority of its government over all entities throughout all of its claimed territory;

(2) prosperity, i.e., production, or economic power; an economy that is sufficient/large in absolute and per capita terms; and

(3) security, the ability to protect sovereignty and prosperity with as much certainty, and as few human and material costs, as possible.

Each is critically important and depends upon the others. Sovereignty allows the effective pursuit of prosperity and security. Security protects sovereignty and prosperity. And prosperity yields both political stability (Hannan and Carroll, 1981) (necessary for sovereignty) and material resources (necessary for security). Moreover, all are necessary for holding, pursuing, or preserving anything else (specific territory, ideological objectives, international prestige, etc.).

The term ‘VR interests’ refers exclusively to these three things: the core, non-subjective, non-IMI-derived interests of a state, which are necessary for assuring its survival, and thus literally vital.

1.2. Interest-Impingement

As for interest-impingement, it is any action whose intended (or likely and reasonably-foreseeable) consequences directly do (or could have directly done, or might in the future directly do) substantial harm to any of the interests (especially VR interests) of another state.

1.3. IMIs

This theory contends that the main determinant of a state’s worldview, non-VR interests, and frequency of impingement upon others’ interests, is its IMI. In reality, there will always be actors within a state’s foreign-policy-making elite who partly or entirely diverge from its dominant IMI, but the theory, as presented here, “black-boxes” the state, treating it as a unitary actor with a single, unanimously-held IMI belonging to one of two ideal-types: the universalistic (broad) and the particularistic (narrow).

1.4. Universalistic IMIs

A universalistic IMI has four closely-related attributes:

(1) It claims universal descriptive validity: it purports to explain how most (social, political, economic, etc.) things, in most places, work.

(2) It claims universal prescriptive validity: it purports to explain how most (social, political, economic, etc.) things, in most places, ought to be.

(3) Universal immanentization of a comprehensive moral-ideological order is at the IMI’s core. This endows the IMI with a revolutionary, utopian, messianic, and teleological quality. It makes the IMI’s universal establishment not only consistent with its own logic, but a core imperative of its worldview and key to its legitimacy and raison d’être.

(4) The IMI confers universal identity upon its adherents. That is, it encourages them to identify with the IMI, with other bearers of the IMI, and with humanity in general. It explicitly subordinates particularistic identities or condemns and rejects them outright. Note that this does not actually prevent universalistic individuals from identifying with their own state. To the contrary, a universalistic IMI means that patriotic and moral-ideological motivations are identical. There are no contradictions or even distinctions between (A) identification with a universalistic morality-ideology, (B) identification with the state defined by that morality-ideology, and (C) identification with the global community that the morality-ideology exalts over the state. In order to ‘act out’ the identity of a universalistic state, one must act in accord with its universalistic morality-ideology. As observed by Carr (1946, pp. 42-43): in pursuing the interests of a universalistic state, one pursues (or believes oneself to be pursuing) the interests of the global community. And by pursuing one’s moral-ideological objectives for the betterment of humankind, one knows that the world is also being made more safe/prosperous/etc. for one’s own state and reshaped in that state’s image.

Thus, universalistic IMIs are not only spatially broad, but also topically broad.

The most common/significant universalistic IMIs are:

Universal-Religious: A faith that is meant for all humanity and that compels its own universal imposition/maintenance, e.g., (Sunni) Islam for the Caliphates. If a religion is not contained within a civilizationalist IMI, then it is likely to be universalistic.

Racialist: A totalizing descriptive and prescriptive understanding of humanity based upon its division not into discrete nations/civilizations, but rather into hierarchically-related ‘races’ that are ostensibly defined by descent/genetics but actually defined by a combination of phenotype/appearance and socio-political convenience., e.g., the Confederate States of America and Nazi Germany, both of which planned vast conquests of ‘lesser peoples’ for the purpose of imposing a ‘racial’ hierarchy well beyond their own initial borders (May, 1973; Weinberg, 2005, Ch. 1).

Communist: e.g., the USSR, the Maoist PRC.

Cosmopolitan-Liberal: e.g., the U.S., especially since 1917/1946.

1.5. Particularistic IMIs

A particularistic IMI, in contrast, is defined by the following:

(1) It may claim descriptive validity within constrained borders that are close or identical to those of the adherent-state. It may purport to explain how some (social, political, economic, etc.) things work within those borders, but its relevance, applicability, and validity explicitly do not extend beyond them.

(2) It does claim prescriptive validity within constrained borders that are close or identical to those of the adherent-state. It does purport to explain how some (social, political, economic, etc.) things ought to be within those borders (e.g., “the Italian state should encompass the Italian Civilization, and affairs within it should be ordered so as to align with and support Italian identity,” however that is conceived.) But the IMI’s relevance, applicability, and moral imperative explicitly do not extend beyond those borders.

(3) Universal immanentization is altogether absent from the IMI. Indeed, due to points (1) and (2), it is impossible and nonsensical. The IMI’s focus lies within relatively circumscribed bounds, and it is only within those bounds that it can and ought to be realized.

(4) The IMI explicitly precludes universal identity. Instead, it defines and focuses upon some specific group, limiting its moral horizons to the borders of that group and pursuing exclusively the distinct interests of that group.

Thus, particularistic IMIs are ‘thin’—sometimes in the range of topics that they cover, and certainly in the range of their moral horizons.

The most common/significant particularistic IMI is civilizationist: directed at encompassing, protecting, and developing, within the state, a civilization, which is an enduring community of a specific culture, e.g., most European states by 1871, and almost all by 1918. (This use of civilization/civilizationism avoids the imprecision of the terms nation (which can also mean state or descent-based (natal) community), national (which can also mean having to do with the state or state-wide), and nationalism (which can also mean patriotism or chauvinism or jingoism.)

1.6. Comparison of Universalism and Particularism

The horizons of an ideal-type universalistic IMI go to the ends of the earth. Those of an actual universalistic IMI might, conceivably, not reach quite that far, but they would get close enough to have roughly the same effect.

The horizons of an ideal-type particularism, on the other hand, are equivalent to the adherent-state’s borders. Whereas those of an actual particularist might not quite encompass all of its borders, or (more likely) might extend somewhat beyond them: e.g., France re. Alsace-Lorraine, Italy re. Italia irredenta, or the somewhat more extreme case of Prussia re. most of the rest of Germany.

‘Hybrid’ states are possible. For example, Nazi Germany was both civilizationist (particularistic) and racialist (universalistic). Notably, it met success in its pursuit of German civilizationist interests (Austria, the Sudetenland, the Danzig Corridor, and Alsace-Lorraine) via realpolitik (e.g., the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact). It destroyed itself when it invaded the USSR in the pursuit of Nazi goals (the destruction of Slavs, of Jews, and of Bolshevism, and ultimately the domination of the world by ‘Aryans’), under the delusions of Nazi ideological doctrine (the inferiority of untermenschen), and contrary to the dictates of realpolitik (there was nothing to be gained from war with the USSR—especially not while still at war with Britain—except for lebensraum, and by 1941, Germany already had more of that than it could use).

However, ‘hybrid’ states will tend to recede towards universalistic behavior: because many of universalism’s mechanisms are self-reinforcing, even a substantial particularist lobby would, over the long run, probably only delay a hybrid state’s more-or-less-complete fall into universalistic patterns of behavior. For instance, if the universalist party is able to secure an even somewhat-hostile policy against an iniquitous foe, this is likely to provoke some sort of response from that state. This would make the universalists only more certain of their initial position, potentially win some non-universalists over to their camp, and at the very least generate an actual conflict between the two states—one that could push even the particularist-realpolitik faction to accept an adversarial policy, notwithstanding the lack of any initial strategic rationale for it.

-

The General Effects of Universalism

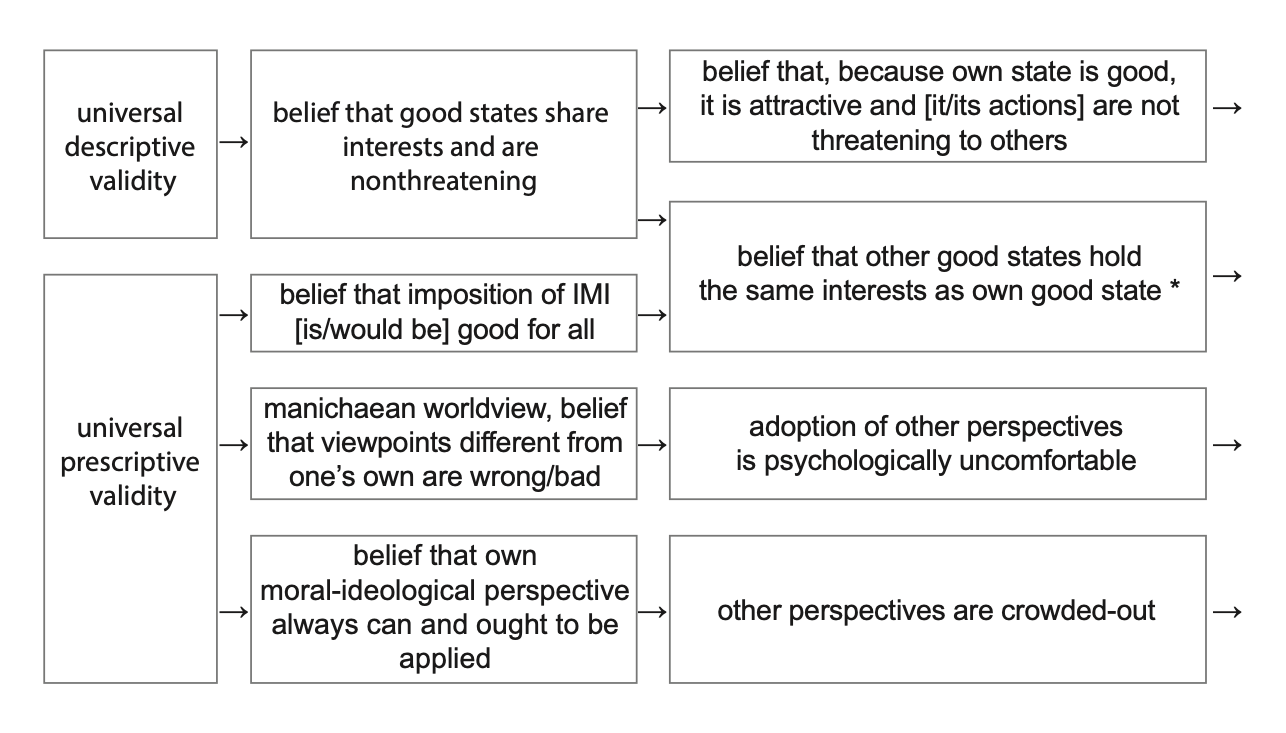

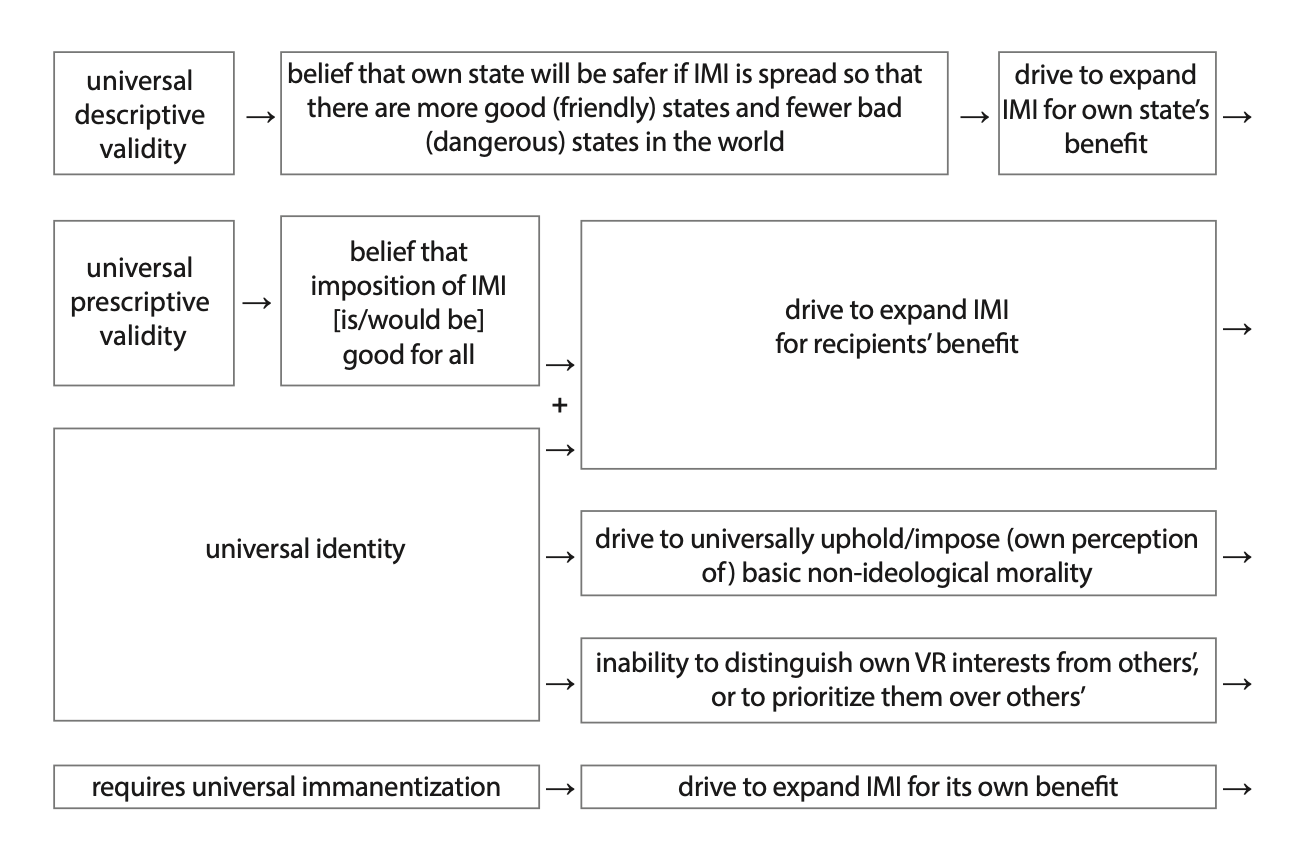

The four attributes of universalism generate an array of beliefs that—sometimes in combination with non-universalism-specific psychological tendencies—will lead to a universalist impinging upon the interests of other states. This impingement comes in three basic forms:

Type 1: Incidental impingement upon the interests of another state as a result of acting with regard neither for other states’ interests, nor for the consequences of impinging upon them.

Type 2: Deliberate opposition to another state on a specific issue, due to one’s own IMI-derived position on the matter.

Type 3: A deliberate effort to generally harm (contain, weaken, mutate, desovereignize, suborn, conquer, destroy) another state, because it is seen as bad per the universalist’s IMI.

(A very comprehensive diagram of universalism and its effects, essentially presenting the entire remainder of this article in schematic form, is available here.)

-

Universalism’s Effects on Perceptions

Types 2 and 3 Impingements are generated partly by condemnation of the other state’s actions and/or of the other state itself.

3.1. Moral Condemnation of Another State’s Actions

Moral condemnation of another state’s actions can be produced in three ways.

Semi-random perceptions of the universalist. Since a universalistic state applies its own moral-ideological framework everywhere, and/or strongly identifies with other actors, it will tend to acquire convictions regarding issues that do not actually have much or anything to do with it. These low-information-based convictions may be semi-random, arbitrary, or outright nonsensical, and may yield condemnation of the other state’s actions.

Conflict with the other state. A clash of interests and/or actions between the universalist and the other state will lead the universalist to morally condemn the other state’s position/actions.

This is because the universalist, sure of its own moral rectitude and possessed of a Manichaean worldview, consciously believes all conflict with itself to be morally wrong. For instance, if the U.S. is a “force for good in the world,” then opposition to it must be “opposition to the good itself;” its “idealist” worldview includes the “Manichaean” perception of opposition as “evil” (Kennedy, 2013, pp. 626-627).

This is also, additionally or instead, because the universalist is subject to the Egocentric Bias in Moral Judgement, and also to an inclination and ability to make moral judgements everywhere. The Egocentric Bias is a general psychological phenomenon, not specific to universalists, according to which—holding the actual moral qualities of a thing constant—people tend to perceive things beneficial to them as more moral, and things harmful to them as less moral (Epley and Caruso, 2004, pp. 178-182).

Moral condemnation of the other state. Finally, given a preexisting negative moral judgement of another state (which an ideal-type particularist is not capable of forming), a universalist will tend to perceive that state’s actions negatively due to Confirmation Bias. Confirmation Bias is the commonly-held psychological tendency to subconsciously seek and overemphasize information that is consistent with extant beliefs, and to ignore information that is contradictory to them, in order to minimize cognitive dissonance and maximize self-esteem. (The latter would suffer from the revelation that one has held wrong beliefs, and thus done the wrong thing.) (Casad, 2007.)

In 1983, Michael Doyle (one of the leading liberal theorists of the Democratic/Liberal Peace) noted the operation of Confirmation Bias in universalistic (specifically Cosmopolitan-Liberal) states. Simple conflicts of interest, between a liberal state and a state that it perceives as nonliberal, are interpreted by the liberal state so as to confirm its preexisting fear and hatred of the other state: “as steps in a campaign of aggression against the liberal state.” Even “efforts by [perceived-]nonliberal states at accommodation…become [seen by the liberal state as] snares to trap the unwary” (Doyle, 1983, p. 325).

3.2. Moral Condemnation of Another State

Moral condemnation of another state in general (as opposed to its activities specifically) can, similarly, be produced in three ways.

Other state’s (perceived) nonadherence to the universalist’s IMI. If the other state does not adhere (or is not seen as adhering) to the universalist’s IMI, this inherently makes it bad in the universalist’s worldview. The perception of a failed attempt to adopt the universalist’s IMI will also be condemned. First, because the universalist’s faith in its own IMI means that the fault must lie with the other state, which either did not genuinely try to implement the ideology or is somehow unworthy of it. And second, because, if the universalist assisted with the implementation attempt, then the universalist will be driven to displace fault for implementation-failure away from itself and onto the other state; driven both by universalism-produced certainty in its own rectitude, and by the commonly-held Self-Serving Bias—the psychological tendency to credit our successes to our own competence or character, but to blame failures on circumstance or on other people, thus maximizing self-esteem (Campbell and Krusemark, 2007).

Conflict with the other state. A universalist’s Manichaean worldview (produced by the subjection of everything to its single moral-ideological system) will incline it to consciously perceive/define its adversaries—including states with which it has conflicts of interests and/or of actions—as bad (e.g., Kennedy, 2013). Because adversarial status by definition makes a state bad, or because adversarial status reveals a state to be bad, since only the bad would be adversarial. (e.g., the Democratic Peace Theory, by stating that democratic (good) states will not be enemies of the U.S., implies that all enemies of the U.S. must be nondemocratic (bad).)

Morally-condemned actions by the other state. Finally, moral condemnation of the other state’s actions—arising from any of the three sources listed in Sec.3.1—directly and logically leads to moral condemnation of the state itself.

All three of these mechanisms may be intensified by the Fundamental Attribution Error, which is the psychological tendency, in evaluating the causes of another’s behavior, to underestimate the causal effect of circumstances and to overestimate the causal effect of the actor’s internal attributes (character, disposition, competence, etc.). In particular, the Error manifests in an excessive likelihood to believe that an actor has done something bad because the actor is bad. The Error occurs, at least in part, because actors are more ‘visible’ (to an observer) than are the conditions to which they are responding (some of which may not be visible at all to the observer) (Gawronski, 2007). This phenomenon is commonly-held, not specific to universalists, but it will interact with the above three mechanisms to reinforce a universalist’s moral condemnation of another state. The universalist will be inclined to believe that:

- the other state failed to implement the universalist’s ideology because the other state is bad and did not want to—rather than, e.g,. because the other state had limited resources, or because it made a mistake;

- the universalist is in conflict with the other state because the other state is bad—rather than e.g., because the other state is pragmatically pursuing its own interests;

- the other state has not only done something morally wrong, but has done so because it is inherently bad and wanted to do evil—as opposed to e.g., because the action was the least bad option available to it.

3.3. The Resulting Disconnect Between Perceptions and Reality

An especially significant consequence of the above phenomena is the universalist’s ability and tendency to form moral-ideological judgements that have very little connection to the true nature of the things (e.g., regime type) to which the universalist thinks that it is responding. Instead, these judgements are likely to be determined in large part by the universalist’s preexisting view of the other state, by its relations with the other state (including the extent to which it impinges upon the other state’s interests and meets resistance in doing so), and by its low-information, semi-arbitrary perception of the positions, actions, and nature of the other state. The influence of these things is only increased by the depth and complexity of universalist IMIs, which makes them malleable enough to support almost any conclusion.

Peceny (1997) argues that the U.S. and Spain were, in 1898, both “partially democratic states” (p. 418). Yet Americans, who certainly saw the U.S. as democratic, “almost universally viewed Spain as a non-democracy” (p. 421)—a “perception that…allowed [the U.S.] to go to war with [Spain]” (pp. 427-428). More generally, Peceny concludes that liberal universalists’ “subjective judgments about the liberal status of potential allies or adversaries can often be more important than the concrete, objectively measurable characteristics of these states” (p. 416).

Oren (1995) argues that “the reason we appear not to fight ‘our kind’ is not that objective likeness substantially affects war propensity, but rather that we subtly redefine ‘our kind’” (p. 178). And it is not only the standards that are changed, but also the evaluations of how well other states measure up to them. For instance, “America’s entry into the war in 1917 led to a more radical change in its image of Germany, including a re-characterization of the German political system. It was then that the sharp dichotomy between ‘autocratic’ Germany and democratic America was born” (p. 155).

Oren cites Russia and Japan as two other states whose natures “underwent a substantial transformation in the American mind” as their behavior became increasingly or decreasingly desirable to the U.S. (p. 181). (In the case of Japan specifically, other work agrees that “predominant images… in U.S. scholarship have been positive when U.S.-Japanese relations have been friendly[,] and have turned critical when the relationship has been more adversarial” (Samuels, 1991, p. 19)). The pattern by which a state’s “image has shifted in a decidedly negative direction,” simultaneously to the “onset of a conflict” with that state, “strongly suggests that the changes have been driven as much by America’s changing rivalries as by the emergence of new facts about the regime[s]” of its rivals (Oren, 2005, pp. 9-10).

Finally, examining 12 crises between the U.S. and other states that were (at least by the standards of the day) liberal-democratic, Owen (1993, p. 31) finds that groups in the U.S. (and in the other states, for that matter) did “argue for war or peace” based on the other side’s status as “free or unfree,” but that these identifications had little to do with the states’ actual “domestic institutions.”

As for Communist states, they correspondingly tend to see adversaries as non-Communist, regardless of whether that is true. Thus, as the Tito-Stalin split developed, Moscow came to view Yugoslavia as not “truly Marxist-Leninist or Bolshevik” (Kardelj, 1982, p. 217). As the Sino-Soviet split developed, Moscow came to view China as not only “schismatic,” but actually “Trotskyite,” “anti-Leninist,” “nationalist,” “great-power chauvinist,” “petty-bourgeois,” and engaged in attacking and “perverting” the “theoretical and political fundaments” of the Communist movement (Suslov, 1964; Presidium of the CCCPSU, 1964). The Chinese (and Albanians), for their part, saw the Soviets as “revisionists,” “deviationists” and “Social Imperialists” who had abandoned revolution, Stalin, and Communism.

In sum, a universalist’s perceptions and behavior vis-a-vis another state are determined ‘monadically;’ by its own universalism and the interaction of that universalism with other psychological phenomena; not so much by the other state’s actual attributes or behavior.

Note that preexisting, stronger, and/or more salient perceptions will tend to inform and/or override others. For instance, with the start of the Second Chechen War, the U.S. did not see the Wahhabism-Salafism of the ‘Chechen Republic of Ichkeria’, define the ChRI as bad, and then improve its perception of the ChRI’s enemy, Russia. Rather, the U.S. already had an increasingly negative view of Russia, and this dictated a positive view of the ChRI. Perceptions of great powers will tend to be overriding, and those of minor powers, contingent—but this is not always the case. For instance, the U.S.’s extremely positive perception of Israel is likely to always win out if contradicted.

-

Universalism’s Generation of Impingement

4.1. Type 1 Impingement

Negative perceptions then constitute a major source of impingement. However, Type 1 Impingement mostly arises independently of them. Type 1 Impingement is incidental impingement that results from the universalist’s unawareness, rejection, or deprioritization of the other state’s interests. This has four possible origins.

Nonperception of the other state’s interests, or belief that they are not genuinely held (e.g., belief that the other state can be convinced to start thinking properly, to recognize its true interests, to recognize that the universalist is not a threat, etc.). This is produced in up to four ways by universalistic IMIs’ claims to universal descriptive and prescriptive validity:

* This may be supported by the (Social) Projection Bias (also known as the False Consensus Effect), the psychological tendency to overestimate the general prevalence of one’s own attitudes and behaviors. It results because people tend to interact predominantly with those who are similar to themselves (Yurak, 2007), and probably also because people are most frequently and directly exposed to their own thoughts and actions. Although this is a commonly-held psychological phenomenon, not specific to universalists, it will reinforce universalists’ moral-ideological belief that the interests of good states are in harmony. Whereas, for particularists, as indicated below, it will tend to be negated by a view of the international system as comprised of autonomous states, each with its own identity and interests—and even by the ‘projection’ of particularism onto others.

Carr (1946) warned of the utopian’s argument that whatever “is best for his country is best for the world, the two propositions being, from the utopian standpoint, identical” (pp. 75-76). This assumption/belief, that other states’ interests coincide with one’s own, would hinder the universalist’s ability to perceive the other states’ actual interests. And any resulting “clash of interests must…be explained as the result of wrong calculation” by the other state (p. 42). “If people or nations behave badly, it must be…because they are unintellectual and short-sighted and muddle-headed” (pp. 42-43). This, in turn, would suggest that the universalist, instead of altering its behavior, might/should educate the other state regarding what the other state’s true interests actually are (p. 33).

Morgenthau (1948, p. 441) wrote of how universalistic, Manichaean states tend to assume their own interests in the place of others’, to which they are psychologically- and ideologically-blinded: “For minds not beclouded by the crusading zeal of a political religion[,] and capable of viewing the national interests of both sides with objectivity, the delimitation of [their] vital interests should not prove too difficult.”

And Mearsheimer (2018, p. 160), similarly, has written of how universalistic (specifically, Cosmopolitan-Liberal) states are “inclined[,] when engaging diplomatically with [a perceived-]authoritarian country[,] to disregard its interests and think [that] they know what is best for it.”

Dismissal of the other state’s interests, because violation is thought to have minimal consequences. As noted above, the universalist’s understanding of international affairs through the prism of its own IMI can produce the belief that it is attractive and unthreatening to others. It can also produce the belief that the universalist’s bad adversaries are threatening to other states. Either or both of these beliefs would then imply that other states wish to remain aligned with the (nonthreatening) universalist against its (threatening) adversaries. This, in turn, would mean that the universalist has little to lose from impinging upon other states’ interests, as those states are not in a position to oppose the universalist or align with others against it; the universalist is the ‘only game in town’.

Dismissal of the other state’s interests, because they are held by a bad state. Given a belief that interests are (not) to be respected on the basis of their moral-ideological (il)legitimacy—a belief that is itself derived from the general subordination of foreign policy to non-VR, IMI-derived imperatives—and given a negative perception of the other state, a universalist will be inclined to actively and consciously dismiss that state’s interests as illegitimate and unworthy of accommodation.

Doyle (1983, p. 325) suggests that Cosmopolitan-Liberalism tends to “exacerbate conflicts… between liberal and [perceived-]non-liberal societies,” partly because Cosmopolitan-Liberal universalists believe that “if the legitimacy of state action rests on the fact that it respects and effectively represents morally autonomous individuals, then states that coerce their citizens… lack moral legitimacy.” Similarly, Mearsheimer (2018, p. 164) notes that, “since authoritarian states [violate] the rights of their people, liberal states freed from the shackles of realism are likely to treat [perceived-authoritarian states] as deeply flawed polities not worthy of diplomatic engagement.”

Subordination of the other state’s interests to own overriding moral imperatives. Finally, and most simply, a universalist may consciously dismiss the other state’s interests (and the potential consequences of impinging upon them) as subordinate to the imperatives of the universalist’s own IMI, or it may simply not give any consideration to other states’ interests (or to realpolitik more generally) in the first place.

4.2. Overriding Universalistic Moral-Ideological Imperatives

The latter two sources of Type 1 Impingement (above), as well as the only source of Type 2 Impingement and the first source of Type 3 Impingement (below), are all products of non-VR interests’ dominance over the foreign-policy-making of the universalistic state. This dominance is produced in up to five ways by all four core attributes of universalistic IMIs:

Describing the Cold War, Morgenthau (1948, p. 193) wrote: “[States] oppose each other now as the standard-bearers of ethical systems, each… a supranational framework of moral standards which all the other nations ought to accept… The moral code of one nation flings the challenge of its universal claim into the face of another, which reciprocates in kind. Compromise, the virtue of the old diplomacy, becomes the treason of the new; for the mutual accommodation of conflicting claims…amounts to surrender when the moral standards themselves are the stakes of the conflict.” And this is no less the case for the Second Cold War (Diesen, 2017; Sakwa, 2023, pp. 75-76).

Non-VR, moral-ideological imperatives’ dominance will be reinforced by deontology (‘the logic of appropriateness’), which impels morally-correct actions regardless of the consequences (including for the universalist’s VR interests) (March 1994, ch. 2). Morgenthau (1948, p. 441) accordingly warned against a universalist’s tendency to think “in legalistic and propagandistic terms” and its consequent inclination “to insist upon the letter of the law, as it interprets the law, and to lose sight of the consequences which that insistence may have for [the universalist] and for humanity.”

Non-VR, moral-ideological imperatives will also be prioritized because the long-term consequences of a universalist’s behavior, for its VR interests, will often to be remote, both causally and temporally. As a result, those consequences will tend to be less certain, less psychologically pressing, and simply less obvious, compared to deontological requirements and consequences for non-VR interests.

Only when the harm to a universalist’s VR interests is sufficiently obvious, certain, severe, and immediate will those VR interests have a chance of taking priority. But this restraint, if it emerges at all, will tend to do so only at the very last minute.

Moreover, by that time, the universalist may have drawn so close to the edge that it no longer has much control over whether it falls over: either because it has somehow gotten itself ‘trapped’, or because things are now in the hands of others or of Fate itself. For instance, neither the U.S. nor the USSR opted for the final escalation in the Cuban Missile Crisis. But both did voluntarily draw quite close to the brink, creating a real risk of nuclear war caused by accident or by the other side’s intransigence (Sagan, 1993, Ch. 8–9; Burr and Blanton, 2002).

Thus, military deterrence (unlike diplomacy) has some chance of restraining universalists. But its success (and avoidance of catastrophic failure) is especially dependent (even more than deterrence normally is) upon its being issued early, clearly, persistently, and credibly. And the threatened consequences must be quite dire (potentially to an extent far in excess of what would be needed to deter a non-universalist).

4.3. Type 2 Impingement

Type 2 Impingement is conscious opposition to another state on a specific issue/conflict. It is produced by the combination of (1) the belief (whose production is described in Sec.3.1 above) that the other state’s position/actions are morally-ideologically wrong; and (2) the overriding influence (as described immediately above) of non-VR moral-ideological imperatives upon the universalist’s foreign policy.

4.4. Type 3 Impingement

Type 3 Impingement is conscious general opposition to another state—i.e., an effort to harm (contain, weaken, remold, desovereignize, subjugate, conquer, destroy) it. This type of impingement has two possible origins.

Moral-ideological desire to harm bad states. First, the perception of another state as bad may be coupled with the overriding imperative to harm bad states for the sake of the universalist’s ideology, (perceived) basic nonideological morality, the world, etc.

Doyle (1983) identified this tendency within Cosmopolitan-Liberals: “Liberalism creates both the hostility to Communism, not just to Soviet power, and the crusading ideological bent of policy. Liberals do not merely distrust what [the Communists] do; we dislike what they are—public violators of human rights” (p. 330). It is as a result of this “imprudent vehemence” that “in relations with powerful states of a [perceived-]nonliberal character, liberal policy has been characterized by repeated failures of diplomacy. It has often raised conflicts of interest into crusades; it has delayed in taking full advantage of rivalries within [perceived-]nonliberal alliances; it has failed to negotiate stable mutual accommodations of interest” (p. 324)

More recently, Mearsheimer (2018, p. 164) has argued that “countries pursuing liberal hegemony often develop a deep-seated antipathy toward [perceived-]illiberal states. They tend to see the international system as consisting of good and evil states, with little room for compromise between the two sides. This view creates a powerful incentive to eliminate [perceived-]authoritarian states by whatever means necessary whenever the opportunity presents itself.”

‘Pragmatic’ desire to harm bad states. Alternatively, the perception of another state as bad, if joined with the universalist’s belief that bad states are inherently hostile/aggressive/malign/dangerous/etc., implies that the universalist will actually be more secure if bad states are harmed.

In Cosmopolitan-Liberal states, this belief manifests itself in the Democratic (or Liberal) Peace Theory (DPT): “Because it links American security to the nature of other states’ internal political systems, [DPT’s] logic inevitably pushes the [U.S.] to adopt an interventionist strategic posture. If democracies are peaceful but non-democratic states are ‘troublemakers[,’ then] the conclusion is inescapable: the former will be truly secure only when the latter have been transformed into democracies, too” (Layne, 1994, pp. 46–47).

But Communist states adhere to an analogous Communist Peace Theory, as Marxism-Leninism holds that non-Communist states are inherently aggressive or “imperialistic” (Lenin, 1917), and “in modern conditions, imperialism is the only source of war” (Prokhorov, 1970). Thus, there can be civil wars, anti-colonial wars, “wars between states with opposing social systems,” and “wars between capitalist states” (Prokhorov, 1970)—everything but wars between Communist states.

Of course, these beliefs are not actually true.

Multiple hot or cold wars have been fought between Communist states: Czechoslovakia vs. the USSR; the USSR vs. the PRC; the PRC vs. Vietnam; and Vietnam vs. Cambodia.

As for the DPT, there are numerous cases of war between democracies—and there have not been all that many democracies in history. An incomplete list of those wars, excluding skirmishes and civil wars, through the year 2000, includes:

- France (Polity V democracy score of 6 on 0-10 scale) vs. the Roman Republic (uncoded), 1849

- the UK (7) vs. the South African Republic (uncoded), 1880

- the U.S. (9) vs. Spain (6), 1898

- the UK (7) vs. the South African Republic (uncoded) and Orange Free State (7), 1899

- the U.S. (9) vs. the Philippines (uncoded), 1899

- France (8), the UK (8), the U.S. (9), and others vs. Germany (5), 1914

- Poland (8) vs. Lithuania (7), 1919

- Ecuador (9) vs. Peru (7), 1981

- India (9) vs. Pakistan (7), 1999

(Polity Project 2020).

The Peace has also been repeatedly broken by covert U.S. aggression against democratic states (or, at least, against the most democratic elements of those states’ governments) such as Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), and Chile (1973) (Rosato, 2003, p. 590; Downes and Lilley, 2010). Even if this is technically not considered to violate the DPT, it contradicts the logic of the ‘dyadic’ democratic peace. (Which is the one that theorists claim to actually observe, in which democracies are more peaceful towards one another, but not in general (e.g., Maoz and Russett, 1993; Dixon, 1993; Dixon, 1994; Bueno de Mesquita et al., 1999).) According to this logic, democracies identify with other democracies and consider aggression against them to be wrong.

Now, one might try to restore the Democratic Peace by narrowing it to an absence of overt war between democracies that are republican, liberal by 21st-century U.S. standards, and decades old. Yet this narrowing vastly diminishes the spatial and temporal applicability of the theory, excluding, inter alia: the UK at least until recently, due to the Crown and the House of Lords; the U.S. for most of its history, at least due to the status of African-Americans; and most democracies outside of Western Europe, whose democracy ‘clocks’ tend to be occasionally reset by political upheaval, and/or which do not share the liberal socio-cultural values of the modern Anglosphere and Western Europe.

And such a narrowing would only intensify the DPT’s largest problem of all: the high degree of overlap between ‘democracy’ and U.S. hegemony. Since the U.S. perceives compliant client-allies as good and thus democratic—or at least as more democratic than they actually are (Bush, 2017)—the Pax Americana that it imposes upon them appears to U.S.-aligned scholars as a Pax Democratica. However, if subordination to U.S. hegemony is accounted for, it is such subordination that makes two states less likely to fight one another, while joint (ostensible) democracy becomes statistically insignificant (Rosato, 2003, p. 600; McDonald, 2015, pp. 580-583).

Ultimately, the fundamental and insurmountable obstacle to any Democratic, Communist, or other universalistic Peace remains universalists’ inability to objectively identify other good states. As a result, they cannot behave pacifically towards states that objectively satisfy their criteria for goodness, even if they want to and believe that they are doing so.

However, it is precisely this disconnect between perception and reality that also ensures that a universalistic peace theory will always appear (to its adherents and their academic communities) to hold true. Universalists are able and compelled to condemn their adversaries (see Secs.3.2 and 3.3 above), and this is even reinforced by their respective Democratic/Communist/etc. Peace Theories, according to which conflict with another state means that that state must be bad.

-

The Resulting Hostility Spiral

Issuing from the above universalistic mechanisms for producing animosity and impingement, one key result is the ability of animosity to drive impingement, of impingement to generate animosity, and of animosity to reinforce itself, collectively forming the ‘Hostility Spiral.’

According to Doyle, Morgenthau, Mearsheimer, and Layne, a universalist’s perceptions of another state determine its behavior towards that state. And according to Peceny, Oren, and Owen, a universalist’s relations with another state determine its perceptions of that state. If both are true, negative perceptions and hostile actions would reinforce one another.

Both perceptions and conflict/impingement can also be generated ‘exogenously,’ by mechanisms described above, and thus serve as the ignition for the Hostility Spiral.

The Spiral can generate negative perceptions where there have been none and for which there is objectively no basis, and it can generate conflict where there has been none and where there is no fundamental clash of VR interests.

-

The Consequences of Universalistic Impingement

The crucial result, of all the above, is universalists’ tendency to impinge upon other states’ interests far more than particularists do, and especially in ways that offer little reward but great risk in terms of VR interests.

Moreover, a negative perception of another state, and interest-impingement against it, are more likely if the universalist’s VR interests directly clash with those of the other state, or if the other state genuinely suffers from a moral failing as judged by the universalist’s own standards—but neither of these things is necessary for a universalist to develop a negative attitude or engage in interest-impingement.

Furthermore, even if another state deliberately seeks to avoid conflict with a universalist, and thereby avoid setting in motion the Hostility Spiral, this will not prevent Type 1 Impingement, nor will it prevent Type 2 Impingement resulting from the universalist’s semi-arbitrary development of a moral-ideological position on a particular issue. And in such cases, even conceding to the universalist may not necessarily be sufficient to prevent the Hostility Spiral from initiating.

As a consequence of all this, it makes sense for other states to assume that universalists will engage in interest-impingement, largely regardless of what the other states do. And the other states should/will behave accordingly: relying on military strength for security against the universalist, rather than on the achievement of compromise and a modus vivendi with it; and balancing against the universalist via alignment with states that are less threatening and more able to accommodate the interests of others. This will eventually end badly for the universalist.

Note that, while stronger states might suffer fewer losses as a result of universalistic behavior, and might have more capacity to absorb those losses, such behavior is still suboptimal (and still potentially disastrous). And there are plenty of great powers that are not universalistic and that do not behave universalistically. Particularly dispositive is the case of China, which now has by far the largest economy in the world and lags behind the U.S. in certain other areas (e.g., military projection, international alliances) precisely because of its particularistic IMI and accordingly restrained foreign policy. Thus, IMI is not a function of a state’s power.

-

The Effects of Particularism

The behavior of a state motivated by ideal-type particularism will be radically different from that which has been described above. Absent all of universalism’s four attributes, and thus absent the various psychological phenomena resulting from them, the only things remaining are the five non-universalism-specific psychological tendencies: (social) projection bias, self-serving bias, egocentric bias in moral judgement, confirmation bias, and the fundamental attribution error. Alone, these are insufficient to produce any form of impingement.

As necessary, the reader may consult the following table, which exhaustively lists the features of universalism and explains their status under particularism:

A particularist may, and frequently will, still enter into conflicts via the defense and/or pursuit of:

(1) The particularist’s VR interests (potentially threatened, inter alia, by universalistic states or by states (including particularistic ones; see below) behaving suboptimally)—more or less regardless of the opponent’s power.

(2) Realpolitik net-benefit via (A) impingement upon the interests (including VR interests) of weak states/blocs and (B) limited contestation of the non-VR interests of powerful states/blocs. (But only when this is not likely to provoke balancing, whether by the target or by third parties, that makes the action a net-loss, as is often the result of aggressive expansion.)

(3) The small number of other (e.g., civilizationist) interests that a real-world (not ideal-type) particularist has. As stated in Sec.1.6 above, insofar as a state’s IMI extends beyond its borders, it will behave less particularistically and more universalistically. It will treat objects that lie beyond its own borders but within the borders of its IMI (holy sites, minority populations, entire territories, etc.) as being of supreme importance. If these things are contested by some other state that lies beyond the bounds of the particularist’s IMI, the particularist will fiercely pursue the contested interests, although it still will not behave universalistically towards the contesting state, since that state is not subject to the particularist’s IMI. But it will behave universalistically towards states that are perceived as belonging to its IMI: e.g., Chinese states regarding one another, during China’s various periods of division; China regarding Taiwan in the present day; Russia regarding Belarus and Ukraine in the present day.

Additionally, even ideal-type particularism does not guarantee a restrained and optimal foreign policy. Rather, it merely means that such a thing is not made impossible by universalism. Realpolitik can still be inhibited by inaccurate perceptions or suboptimal objective-setting, produced by: bad information (Jervis, 2010); natural and inevitable errors in human judgement; individuals’ greed or will to power (Morgenthau, 1948); psychologically-generated cognitive errors (Jervis, 1976; Holsti, 1989; Johnson, 2009; Lake, 2010); the incoherence of the objectives of a state’s different factions (Snyder, 1991); an excessive civilizationism that augments subjective love of civilization with belief in its objective superiority (Van Evera, 1994); and other things that can afflict particularists as easily as universalists.

-

Conclusion

This theory is thus not a comprehensive theory of international relations or of state behavior, but rather a theory of how a certain factor (universalism) has major and relatively definite effects upon the overall behavior of states that are host to it. (Particularism also influences behavior in the sense that it means the absence of universalism’s effects, leaving behavior to be determined entirely, rather than partially, by factors beyond the scope of this theory.)

The theory rests on a dichotomy between particularists (mostly civilizationists) and universalists (in the last century and at present, mostly Cosmopolitan-Liberals and Communists). Universalism, by driving frequent interest-impingement that is neither guided by consequentialism nor directed at VR interests, virtually guarantees useless, exhausting, and counterproductive conflict with many other states, and the ultimate failure of a state’s foreign policy. Particularism, as the absence of universalism, provides the possibility that a state will thrive or at least muddle through on the international stage—depending on myriad other factors that are beyond the scope of this project.

This is not the first conceptualization of a particularism-universalism dichotomy. At the dawn of the Cold War, Morgenthau (1948, pp. 268-269) observed that “for the nationalism of the nineteenth century, the nation is the ultimate goal of political action, the end point of political development beyond which there are other nationalisms with similar and equally justifiable goals.” But for modern ‘nationalistic’ (i.e., ‘jingoistic’ and ‘originating from a specific state/society’) universalism, “the nation is but the starting point of a universal mission whose ultimate goal reaches to the [limits of] the political world,” one that seeks “to impose its own valuations and standards… upon all other nations” and which supplies its bearers with a “good conscience and a pseudo-religious fervor” in this crusade.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., Morrow, J.D., Siverson R.M., and Smith, Alastair, 1999. An Institutional Explanation of the Democratic Peace. American Political Science Review, 93(4), pp. 791-807.

Burr, W. and Blanton, T. (eds.), 2002. The Submarines of October: US and Soviet Naval Encounters During the Cuban Missile Crisis. GWU National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 75. National Security Archive, 31 October. Available at: https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB75/ [Accessed 1 October 2024].

Bush, S., 2017. The Politics of Rating Freedom: Ideological Affinity, Private Authority, and the Freedom in the World Rankings. Perspectives on Politics, 15(3), pp. 711-731.

Campbell, W.K. and Krusemark, E., 2007. Self-Serving Bias. In: R.F. Baumeister and K.D. Vohs (eds.) Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 845-847.

Carr, E., 1946. The Twenty Years’ Crisis. London: Macmillan.

Casad, B., 2007. Confirmation Bias. In: R.F. Baumeister and K.D. Vohs (eds.) Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 162–164.

Diesen, G., 2017. The EU, Russia, and the Manichaean Trap. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 30(2-3), pp. 177-194.

Dixon, W., 1993. Democracy and the Management of International Conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 37(1), pp. 42–68.

Dixon, W., 1994. Democracy and the Peaceful Settlement of International Conflict. American Political Science Review, 88(1), pp. 14-32.

Downes, A. and Lilley, M.L., 2010. Overt Peace, Covert War?: Covert Intervention and the Democratic Peace. Security Studies, 19(2), pp. 266-306.

Doyle, M., 1983. Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs, Part 2. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 12(4), pp. 323–353.

Epley, N. and Caruso, E., 2004. Egocentric Ethics. Social Justice Research, 17(2), pp. 171-187.

Gawronski, B., 2007. Fundamental Attribution Error. In: R.F. Baumeister and K.D. Vohs (eds.) Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 367-369.

Hannan, M. and Carroll, G., 1981. Dynamics of Formal Political Structure: An Event-History Analysis. American Sociological Review, 46(1), pp. 19-35.

Holsti, O., 1989. Crisis Decision Making. In: Ph. Tetlock (ed.) Behavior, Society, and Nuclear War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 8-84.

Jervis, R., 1976. Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jervis, R., 2010. Why Intelligence Fails: Lessons from the Iranian Revolution and the Iraq War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Johnson, D., 2009. Overconfidence and War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kardelj, E., 1982. Reminiscences—The Struggle for Recognition and Independence: The New Yugoslavia, 1944-1957. London: Blond & Briggs.

Kennedy, C., 2013. The Manichean Temptation: Moralising Rhetoric and the Invocation of Evil in US Foreign Policy. International Politics, 50(5), pp. 623–638.

Lake, D., 2010. Two Cheers for Bargaining Theory: Assessing Rationalist Explanations for the Iraq War. International Security, 35(3), pp. 7–52.

Layne, Ch., 1994. Kant or Cant: The Myth of the Democratic Peace. International Security, 19(2), pp. 5-49.

Lenin, V.I., 1917. Империализм как высшая стадия капитализма [Imperialism as the Highest Stage of Capitalism]. Petrograd: Parus.

Maoz, Z. and Russett, B., 1993. Normative and Structural Causes of Democratic Peace, 1946–1986. American Political Science Review, 87(3), pp. 624–638.

March, J., 1994. A Primer on Decision Making. New York: Free Press.

May, R., 1973. The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire, 1854–1861. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

McDonald, P.J., 2015. Great Powers, Hierarchy, and Endogenous Regimes: Rethinking the Domestic Causes of Peace. International Organization, 69(3), pp. 557-588.

Mearsheimer, J., 2018. The Great Delusion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Morgenthau, H., 1948. Politics Among Nations. New York: Knopf.

Oren, I., 1995. The Subjectivity of the “Democratic” Peace: Changing U.S. Perceptions of Imperial Germany. International Security, 20(2), pp. 147-184.

Oren, I., 2005. Our Enemies and US: America’s Rivalries and the Making of Political Science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Owen, J.M., 1993. Testing the Democratic Peace: American Diplomatic Crises, 1794–1917. PhD Dissertation, Harvard University.

Peceny, M., 1997. A Constructivist Interpretation of the Liberal Peace: The Ambiguous Case of the Spanish-American War. Journal of Peace Research, 34(4), pp. 415-430.

Polity Project, 2020. Polity V (Polity-Case Format, 1800–2018). Center for Systemic Peace, n.d. Available at: https://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html [Accessed 1 October 2024].

Presidium of the CCCPSU (Central Committee of the CPSU), 1964. Декрет “О борьбе КПСС за сплоченность международного коммунистического движения” [Decree “On the Struggle of the CPSU for the Unity of the International Communist Movement”]. Правда [Pravda], 3 April, p. 1.

Prokhorov, A.M. (ed.), 1970. Война [War]. In: Большая Советская Энциклопедия — 5 [Great Soviet Encyclopedia — 5]. Moscow: Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, p. 282.

Rosato, S., 2003. The Flawed Logic of Democratic Peace Theory. American Political Science Review, 97(4), pp. 585–602.

Sagan, S., 1993. The Limits of Safety. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sakwa, R., 2023. Crisis of the International System and International Politics. Russia in Global Affairs, 21(1), pp. 70-91.

Samuels, R.J., 1991. Japanese Political Studies and the Myth of the Independent Intellectual. In: R.J. Samuels and M. Weiner (eds.) The Political Culture of Foreign Area and International Studies: Essays in Honor of Lucian W Pye. Washington: Brassey’s.

Snyder, J., 1991. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Suslov, M., 1964. О борьбе КПСС за сплоченность международного коммунистического движения [On the Struggle of the CPSU for the Unity of the International Communist Movement]. Правда [Pravda], 3 April, pp. 1-6.

Van Evera, S., 1994. Hypotheses on Nationalism and War. International Security, 18(4), pp. 5-39.

Weinberg, G., 2005. Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yurak, T., 2007. False Consensus Effect. In: R.F. Baumeister and K.D. Vohs (eds.) Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 343-344.