Few political observers consider the conflict in Ukraine an internal affair. Both domestic and foreign analysts tend to interpret events in the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics not just as attempts to settle old scores between separatist-minded residents of peripheral regions and the central government, but as a standoff between the United States (and to a lesser extent other NATO countries) and Russia; or even as a new round of the Cold War. However, experts’ opinions vary regarding the underlying factors for the crisis.

Some argue that the root causes lie in an increase of expansionist sentiment within the Russian elite. The most radical advocates of this view blame Russian President Vladimir Putin’s imperial ambitions. Others point to the aggressive policies the U.S. and NATO pursued during the escalation of the conflict in eastern Ukraine. NATO’s persistent eastward expansion and attempts to keep a tight grip on the domestic policies of Russia’s closest neighbor could only evoke Moscow’s natural resistance, they say. The aforesaid opinions vary not only in “Who is to blame?;” but also in “What is to be done?” Assigning blame predetermines the content of mutual grievances and, therefore, is the key factor in devising a strategy to deescalate tensions in the region.

The choice between two opposite viewpoints (as well as a compromise vision that puts the blame on both sides) depends largely on what information is available to analysts. A traditional foreign policy analysis is usually based on an impersonal notion of national interests. Governments are regarded as rational agents seeking to maximize benefits in the geopolitical arena. However, the standard perceptions of how the situation is seen by the immediate participants in the political process – top statesmen, diplomats, military commanders, industry executives, and those responsible for formulating and delivering relevant information to the public at large – quite often oversimplify the situation.

In his study of Russian elites, U.S. political scientist William Zimmerman offers a clear idea of how the country’s leaders perceive the current international situation and Russia’s place in the world. From 1993-2012 six opinion polls were conducted of senior officials in the Russian establishment. The respondents can be divided into seven groups: the military; mass media figures; education and science scholars; civil servants (representing the executive branch); State Duma deputies; legislators (members of committees in both houses of parliament) who work with foreign affairs; chiefs of state-run corporations; and big business tycoons. All were asked questions about Russia’s foreign policy priorities, the main means of achieving key goals on the international stage, various internal and external threats to national security, etc.

In the context of the current crisis in Ukraine, most telling are the Russian elite’s views concerning Russian-U.S. relations, national interests and the effectiveness of various means of reaching foreign policy goals, and also the way these views change over time. The data below illustrate the responses to three questions:

1) Do you believe the United States is a menace to Russian security? Response options: yes/no.

2) There is a divergence of opinion regarding Russia’s national interests. Which of these two statements is closer to your viewpoint: a) Russia’s national interests should be confined to its current territory; b) Russia’s national interests extend beyond its current territory?

3) Here are two statements about the role of military power in international relations. Which one is closer to your viewpoint: a) military power will always decide everything in international relations; b) it is the economic potential of the country, and not the military prospects, that determines the country’s place and role in the world.

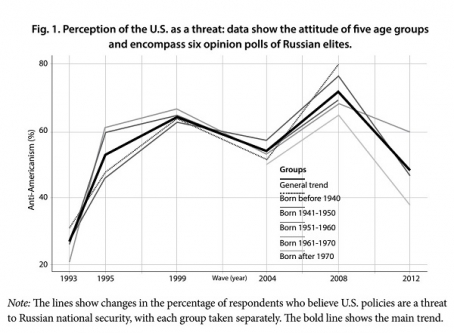

The data indicate that each year more members of the Russian elite increasingly believed that the U.S. is a threat to Russia’s national security (Fig. 1). The sentiment of the current establishment may vary depending on the situation today – the peaks observed in 1999 and 2008 obviously correlate with the crises in Russian-U.S. relations over the conflict in Kosovo and the Russian-Georgian war, but the general trend is unequivocal: in 1993, only one-quarter of those polled regarded U.S. policies as a threat to Russian national security, while in the relatively liberal year 2012, when the “reset” policy had not been curtailed completely, such views were shared by nearly half of those polled.

Among the numerous theories explaining the origins of anti-Americanism in Russia, the two most popular are the instrumental and the situational. Those who support the situational theory maintain that the growth of anti-Americanism in Russia is temporary and stems entirely from the current state of affairs. When relations get worse, such as in 1999 and 2008, negative attitudes surge. The situational theory relies on the data of mass opinion polls. However, anti-U.S. sentiment rose inside the elites even before the events that experts see as catalysts of anti-Americanism. A sharp growth in the elite’s critical view of the U.S. was observed back in 1995 and can be attributed to the war in Bosnia. Yet those hostilities had flared up as early as 1992 and the Western and U.S. stance had been well known from the outset. But a large share of the Russian elite in 1993 saw the U.S. as a partner, not an enemy.

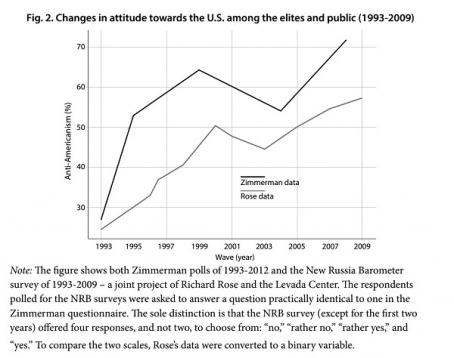

Advocates of the instrumental theory stipulate that powerful groups artificially engineered dislike of the U.S. in order to gain a competitive edge in the election; later, this sentiment was used as the ideology of a “besieged fortress.” The authoritarian regime consolidated because it had to resist an external threat stemming from the United States’ imperialist and ostensibly anti-Russian policies. Also, empirical evidence exists to support that theory. A comparison of the changes in attitude towards the U.S. among the establishment and general public (Fig. 2) reveals that the growth of anti-Americanism among the elites outpaces the corresponding trend among the public at large. In fact, it is quite possible that anti-Americanism in Russia is orchestrated from above.

However, this does not explain why the negative attitude towards the U.S. is so widely spread among the elite. The use of social sentiment as a political instrument may result in the “manipulator effect,” when the persuader begins to believe the things s/he would like the audience to believe. But in that case the growth of anti-Americanism inside the elite should follow the general proliferation of anti-American views in Russia. Yet the available data suggest the contrary. Thus there might be another reason researchers have overlooked behind the Russian elite’s strong negative attitude towards the U.S.

A plausible alternative explanation for widespread anti-Americanism in Russia may be derived from Liah Greenfeld’s “re-sentiment” concept. Friedrich Nietzsche coined the term “re-sentiment” in his Genealogy of Morals. Originally it was used to describe a situation where a positive attitude towards an object and the wish to possess it runs counter to the impossibility of acquiring it; as a result, the positive feeling is transformed into denying the value of the original goal. Greenfeld adapted the re-sentiment concept to explain the spread of nationalist ideologies in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. Greenfeld applied this term to the phenomenon when the national elite and the masses developed a negative attitude towards a country that once had been seen as an example for development.

Greenfeld argues that the re-sentiment effect manifests itself in the following way: initially, a country sees the successful experience of reforms in another country as a model, but if the attempt to borrow experience fails to achieve the expected results, then people will develop a sense of frustration and aggressive enmity towards the country that was once seen as a beacon. The elites (especially intellectuals) play a special role in this process: firstly, they create an ideal to emulate (as Britain was for French intellectuals in the first half of the 18th century, or France was for the Germans during the Napoleonic wars), but then, becoming disillusioned, they turn their backs on the recently worshiped idols.

Something similar happened in post-Soviet Russia. The ruined hopes for a better socio-economic situation after the transition from the socialist system to a free market economy and a new form of government impacted relations with the U.S. During perestroika the younger generation was optimistic about the future; the U.S. was a benchmark for change in Russia. Moreover, amid the euphoria at the end of the Cold War the other superpower was viewed as a future ally and partner capable of doing a great deal to help improve the situation in Russia. Falling standards of living and Russia’s shaky foothold internationally, which the reforms of the early 1990s had brought about, cooled the early optimism of the advocates of democracy and a free market economy. The disillusionment manifested itself in attitudes towards the U.S., which, contrary to the hopes of liberal ideologists, did practically nothing to help Russia into a “bright future.”

The growing distrust and enmity towards the U.S. recorded in opinion polls is a natural outcome from removing the rose-colored glasses of the perestroika era. Many members of the Russian elite were quick to blame the U.S. after they realized Russia had not become a full-fledged member of the Western world overnight; the transition to democracy and a free market economy had bred countless problems; Russia’s Western partners were by no means eager to extend a helping hand to resolve any of these issues; and a former superpower had turned into a second-rate actor in international affairs. As a result, Russia rejected the political and economic institutions of Western democracies and the country that embodied those values.

As for the United States, it did not lift a finger to help Russia make it through the painful period of reforms, but at the same time the U.S. did not hesitate to take advantage of its former adversary’s weaknesses. The U.S. took Russia’s place in Eastern Europe (and not only there), and became the world’s sole superpower. Additionally, the liberal reforms launched in order to bring Russia closer to the Western world and rearrange Russia’s political and economic life along new lines were accompanied by social and economic disasters.

By 1995 a majority of the Russian elite started to see the U.S. as a threat to security and order in Russia (at this time NATO launched the first phase of its eastward expansion and Russian GDP slumped to an all-time low). But that feeling had not yet risen to the political level. Moreover, since Russia’s leaders depended on the ideology that had propelled them into office, television pushed ahead with its “reunion-with-the-family-of-civilized-peoples” propaganda. By virtue of that factor, the anti-Americanism at the grassroots level, heavily dependent on the content offered by the mass media, was largely falling behind the sentiment of the elites. The financial crisis of 1998 buried even the shade of hope that liberal reforms were able to guarantee a better life for the people. The Kosovo crisis and NATO’s air strikes against Belgrade in 1999 were glaring evidence that Russia had lost its superpower status. At that moment the frustration of the ruling elite reached a point where it began to fill the TV screens. Widespread anti-Americanism among the public was beginning to catch up with that of the elite.

Having become widespread at the grassroots level, anti-Americanism has turned into an independent factor for domestic policies. Those political forces that tried to ignore it (for instance, the Yabloko party) had to quit the political scene. Others have responded to the mainstream trend – albeit with a varying degree of sincerity – and support the prevailing sentiment in society. The younger generation who had grown up in the relatively calm and bright first decade of the new century were initially peaceful towards the U.S., even more so since migrants competed for the role of the “significant other.” But each new international crisis, including the current one in Ukraine, pulls Russia’s younger generation onto the track of anti-American sentiment. Crises consolidate the public and elites, which present a united front in the face of a common threat. Anti-Americanism in Russia is rising to an instrumental dimension; each year it is becoming an ever more tangible factor in mapping Russia’s domestic and foreign policy course.

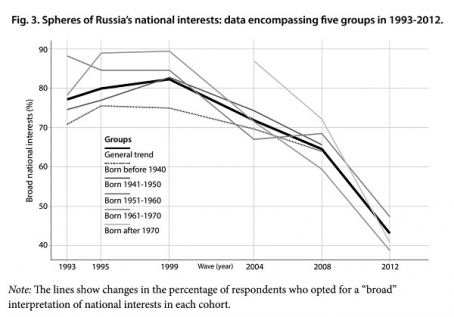

But are the Russian authorities prepared to go further than just using the image of an aggressive United States as a bogeyman to let out the steam of negative sentiment, avoid domestic political turmoil, and shift towards an outright confrontation with the U.S.? A large segment of the Western expert community maintains that expansionism and imperial ambitions are innate features of the Russian ruling class. Yet the actual data do not confirm this vision. On the contrary, increasingly fewer people among those who can be rated as Russia’s power-wielding classes believe that Russia should get involved in major imperial projects in far-away countries and, according to the latest findings, even in Russia’s closest neighbors. Whereas in the early 1990s nearly 80 percent of those questioned in surveys of Russian elites supported a pro-active foreign policy, in 2012 the share of such respondents had dropped to 43.8 percent (Fig. 3).

One confirmation of this interpretation is that respondents belonging to the “mass media” group, although firmly committed to the “broad” concept of national interests, are certain that “soft power” plays the decisive role in foreign affairs (this view is shared by 85.3%). In contrast to other professional categories, the career military and representatives of executive agencies attach the greatest importance to the armed forces (70.6% and 45.5%, respectively).

At the same time the aforesaid data by no means indicate that the Russian authorities have reconciled themselves to Russia’s position as a second-rate power. These figures merely show that on the medium tier of power there are ever more people who see domestic policies and the affairs of Russia’s closest neighbors as far more important than claims to global leadership. It remains unclear, though, whether this trend is a sign of “pragmatism” and a departure from “romantic” imperial rhetoric. Whatever the case, even in 2012, 40 to 50 percent of the elite (depending on the age category) adhered to the “broader” concept of national interests. Such views were somewhat more popular among older citizens. The Zimmerman poll questioned people representing the middle stratum of the elite; those who make major foreign policy decisions today are not easily accessible for researchers.

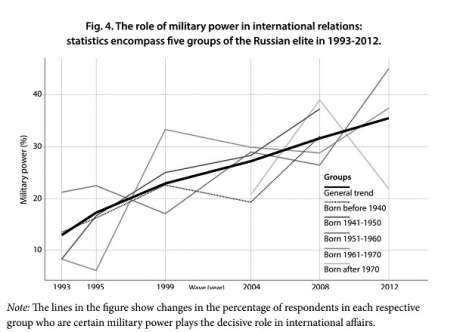

Nevertheless, ever fewer people in the elite regard Russia’s role in world affairs in terms of global leadership. On the contrary, the number of those certain that military force is a decisive factor in international relations has been growing. This number stood at 12.3% in 1993 and at 35.4% in 2012.

In what cases can the use of military force be justified in the eyes of the elite? The following observation is crucial in order to understand the current situation: in 2012 a majority of respondents agreed that the army could be used to protect the interests of the Russian-speaking population in other former Soviet republics (Fig. 4). The percentage of those who regard the oppression of the Russian-speaking population as a reason for military intervention is comparable to those who believe it is permissible to use force for such purposes to protect Russia’s economic interests or to maintain the balance of power with the West: 68.9% against 70.6% and 69%, respectively. Although here once again one does not see the degree of unanimity observed on the issues of protecting territorial integrity and national interests (more than 99% in both cases).

This kind of attitude produced a situation in which anti-Americanism became part and parcel of the outlook of Russia’s ruling elite. But this variety of anti-Americanism should not be considered a fundamental ideological feature of the Russian establishment; rather it is a feeling of injured pride that might have faded away in time. The lessening of anti-American sentiment inside the elite in 2012 indicates that the U.S. was not the absolute evil in the eyes of those in the middle echelon of power. Bearing in mind the elite’s growing belief that Russia should not pursue a global geopolitical agenda, a conflict might have been avoided. Increasingly, the ruling officials agreed that Russia’s sphere of national interests should be confined to its neighboring territories. Although these people belonged to the medium tier of power, in time they would gradually move up the career ladder to start building a foreign policy in conformity with their own ideas, while today’s “hawks” would steadily lose influence.

The worsening of the situation in Ukraine and the ensuing crisis in Russian-U.S. relations has considerably reduced the probability of this scenario.

No one had predicted the current surge of “expansionism” and “revanchism.” Although a number of top officials, including President Putin, have made statements that could be interpreted as an intention to restore the Soviet Union or expand the sphere of Russian influence, such declarations seldom entail specific action. Even the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union could hardly be considered an attempt to expand territory—none of the participating countries want to share political independence. The integration processes in the post-Soviet space conform to general world trends towards unification of the legal space that controls economic interaction within the framework of large geographic regions. Establishing close cooperation with neighboring states by no means indicates that top Russian officials are dreaming about restoring the empire: such claims require decisive proof that no one has been able to provide so far. Official rhetoric could be viewed as an attempt to play on public sentiment in order to maintain political stability.

The latest findings available from the Zimmerman surveys are dated 2012. One can postulate with a high degree of certainty that by now the number of those in the elite who regard the U.S. as a hostile state has grown considerably, just like the number of “hawks.” Opinion polls indicate that 2014 saw a noticeable upsurge in anti-American sentiment in Russia. The Levada Center says that in May, Russians’ dislike of the U.S. reached an all-time high: 71% said that their attitude towards the U.S. was bad, whereas in the early 1990s this group was smaller than ten percent. Bearing in mind that the level of anti-Americanism within the elites in the previous two decades was above the national average, one may speculate that there are few people at the top with pro-American views (or at least those willing to state their opinion in public). No doubt the elite has witnessed an increase in the number of the supporters of expansionist policies and in the number of the “hawks,” who claim that military force is the sole method to resolve international disputes.

* * *

Several conclusions can be made based on this analysis of surveys of the Russian elite.

A large percentage of the elite considers U.S. foreign polices a challenge to Russia’s national interests. The U.S. is not just a bogeyman, an enemy image meant for the domestic audience. Many high-placed Russians quite earnestly see the U.S. as an obvious and outright threat. In the eyes of the elite, such an attitude is largely an effect of U.S. government policies. Instead of promoting Russia’s fast integration with the world community (something the Russian elite had hoped for all along), the Americans took advantage of Russia’s temporary weakness in pursuit of local geopolitical aims and did nothing to cushion the mammoth economic and reputation costs Russia had to sustain during the reform period.

Nevertheless, although the bi-polar Cold-War-style mentality is still quite widespread among the rulers of Russian society, it is not a fundamental feature of their global viewpoint. Rather, Russia’s sense of being insulted and disappointed after it failed to join the “premier league” is behind this mindset. However, each subsequent confrontation between Russia and the U.S. will add strength to that kind of mentality and help proliferate it. As a result, in order to keep the support of the elites and the public, the authorities will have to conduct an increasingly harsher foreign policy.

The Russian elite does not lay claim to global domination. At the same time, it sees Russia’s closest neighbors as a natural sphere of national interests. There is no doubt that Russia’s current leaders are prepared to use military force to defend the country’s interests, including those in the near abroad. It is another question if this stance is a threat to someone or just a reflection of the natural train of thought of any national elite. However, this is essential background information any partner or opponent of Russia must take into account before starting talks on ending the crisis or building a constructive policy of interstate relations.