Ukraine is unstable. It has been off balance for the past six months or so. The next month after the unconstitutional coup in Kiev on February 22, 2014 the country lost nearly five percent of its territory. Its population dwindled by nearly two million. The risk of further decay emerged in April 2014, when the Lugansk and Donetsk regions proclaimed themselves as people’s republics and held referendums on their own independence – in other words, on separation from the Ukrainian state.

In defiance of general expectations, the May 25 presidential election has not brought about political stabilization to this day. On the contrary, Kiev’s armed conflict with the Donetsk and Lugansk republics kept growing and causing ever heavier loss of human lives. Towards the end of the summer of 2014 it became nakedly clear that Ukraine’s ruling elite was unable to achieve consensus on solutions crucial to the very existence of the country on the world map, let alone on a strategy for building Ukrainian statehood. It will not be an exaggeration to say that in 2014 Ukraine for the first time over the years of independence is faced with a real risk of dropping out of the historical process it joined shortly before as one of Europe’s largest countries possessing a vast economic potential and impressive natural and labor resources.

The Ukrainian political crisis as such would have hardly drawn such an extensive international response but for a set of historical and geopolitical factors. First, Ukraine within its current borders was formed on the territorial (not ethnic) principle to incorporate historical populations of other countries (Poland, Hungary and Russia). Naturally, Ukrainian domestic and foreign policies remain the focus of its near neighbors’ unflagging attention. As far as geopolitics is concerned, one should bear in mind Ukraine’s influence on the regional balance of power between Russia and the European Union, its status of a major transit-country of energy resources, and its place in the pan-European system of security.

Small wonder therefore that the events in Ukraine – or rather their interpretation – promptly became an apple of discord between major regional and international players – Russia, on the one hand, and the European Union, the United States, Canada, Australia and Japan, on the other. The mutual sanctions and soaring tensions go ever farther beyond the bounds of the political space to encompass other spheres of public life and upset multinational, cultural, professional and business ties that had taken decades to establish. All this has brought to the fore the urgent need for finding a way out of the Ukrainian crisis on conditions acceptable to all.

However, attempts to identify a solution inevitably run against inability to analyze the Ukrainian crisis properly. On the one hand, the academic community is experiencing a dire shortage of impartial information, which greatly hinders on-line analysis of the latest events. On the other hand, the situation in Ukraine is changing too rapidly, so even the latest information available promptly turns irrelevant. The remedies being proposed today may well prove belated and utterly out of date tomorrow.

A solution to this problem may lie elsewhere, if the researchers shift the emphasis from the hazy future of Ukraine per se to the trends that have brought the country to where it is today. True, such studies will not produce clear guidelines for Ukraine to follow, but they will surely help formulate the basic conditions that are an absolute must for internal (and consequently regional) stabilization. In this context, bearing in mind the current disintegration tendencies, the issue most topical of all is about the very possibility of long-term normalization: Is today’s Ukraine as a state past the point of no return and hopelessly sliding towards utter collapse and decay? If not, is there a mechanism that can put it back on the track of positive development?

SOURCES OF UKRAINE’S INSTABILITY

Many politicians, scholars and journalists prefer to blame Ukraine’s incessant turmoil on external factors, such as commercialization of Russian policies in the 2000s (transition to free market economy rules in trade), the world financial crisis, and competition between the European and Eurasian integrations that left no chance for Kiev to selectively participate on beneficial terms in the free trade zone with the EU and in the Customs Union with Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus.

It goes without saying that the impact of external factors on Ukraine’s development should not be underestimated. However, if one takes a closer look at what has been going on inside of the country, it will become clear why Ukraine throughout most years of independence was unable to meet some challenges and, as a result, in 2014 proved the sole country in the region that best matched the term “failed state.”

The above-mentioned territorial principle of Ukraine’s formation as a nation is number one internal factor of the sort. In 1991 the right to Ukrainian citizenship was granted to all residents of the territory without preconditions, and in 1996 the preamble to the Ukrainian Constitution defined the Ukrainian nation as “citizens of Ukraine of all nationalities.” As a result, the Ukrainian population proved very mixed in terms of self-identification. Hence the demand for a great variety of political programs, often conflicting with each other. In other words, the assorted composition of the Ukrainian population objectively hindered the emergence of a national idea, while political forces subjectively failed to propose such an idea, based on other, non-ethnic principles.

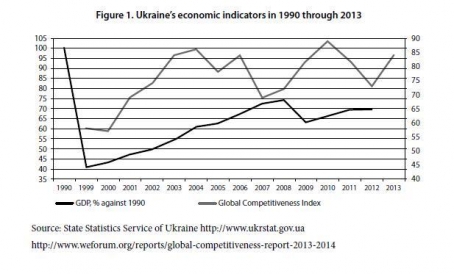

The economy’s low competitiveness is another internal factor in the ineffectiveness of Ukraine as a state. At the very beginning Ukraine boasted vast natural and human resources and diversified industries. Regrettably, during the first decade of independence a considerable share of that potential was wasted. Towards the end of the 1990s Ukraine’s GDP had slumped to 40.8 percent of the 1990 level; in 2004 that parameter was up slightly to 61.1 percent only to stay there ever since. Qualitative parameters remained at a low level, too. Throughout the 2000s Ukraine moved up and down between 60th and 90th places in the Global Competitiveness Report. Its higher rankings in the early 2000s are explained by shorter lists of countries included in the rankings (Fig. 1).

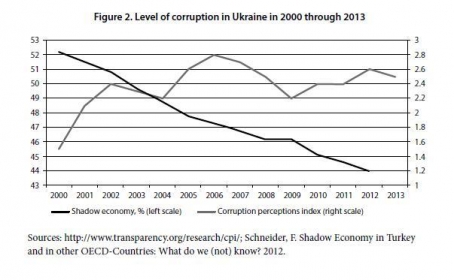

For instance, although the scale of the shadow economy decreased somewhat (although very insignificantly), the level of corruption remained rather high, and corruption itself had extensively spread to the top echelons of power, fomenting interpenetration of political forces and business. It is noteworthy that in a 2012 opinion poll Ukrainians named corruption (31.1%) and the authorities’ obsession with their private interests to the detriment of society’s needs (18.2%) as the root causes of the unsatisfactory socio-economic and political situation (http://www.razumkov.org.ua/ukr/poll.php?poll_id=615).

Also, the second half of the 2000s saw further polarization of the public opinion. Central and western regions of Ukraine increasingly associated themselves with the European civilization and were pressing for fast-tracked integration with the European Union and NATO, while the population in the east was campaigning for a wider dialogue with Russia. This was the main hindrance to the emergence of consensus in society and in political quarters over Ukraine’s strategic issues.

In the course of democratization Ukraine fell into a “transition trap.” Countries with economies in transition and unstable socio-political models tend to show a certain decline in their development, which manifests itself in the deterioration of government institutions and economic indicators, etc. A country that has managed to cope with such a decline can expect faster growth in welfare than before the reform. Neither the Yushchenko administration, which initiated European-style reforms, nor the Yanukovich administration, which made certain steps towards centralization of power and consolidation of the state, succeeded in stemming the slide down. At the beginning of the 2010s, Ukraine found itself by a number of qualitative economic indicators way behind not only more democratic countries of the region, but also authoritarian Belarus.

It would be wrong to say that in 2013-2014 these internal factors had come to a head, to trigger a government coup. Likewise, it would be wrong to postulate that these factors alone were its sufficient cause, as it is pretty clear that the Ukrainian events were largely caused by inapt actions of Ukrainian politicians. However, these factors have certainly played a key role in the ongoing crisis of governance, because throughout decades they left no chance for determining the country’s own independent vector of development that would match Ukraine’s multifaceted nature. Small wonder therefore that the lack of such a vector made Ukraine’s politicians so perceptive to external factors, i.e., vectors offered by its foreign partners.

Thus, Ukraine’s current destabilization is a natural outcome of internal destructive processes, although somewhat unexpected at this particular moment. In 2014, against the backdrop of the country’s “vectorless” development and in the context of a growing political crisis, the internal factors were an important cause of, on the one hand, and fertile soil, on the other, for processes very harmful to its statehood.

Internal socio-political heterogeneity sparked armed conflicts threatening Ukraine with further disintegration.

The ineffectiveness of the Ukrainian economy led to yet another economic slump and decline in living standards, which in the longer term may aggravate and cause more unrest.

Inefficient and corrupt government institutions have caused a socio-political chaos, where the authorities’ ability to cope with problems (let alone achieve the declared goals) within the current political system and statehood looks very doubtful.

NATIONAL DISINTEGRATION

In March 2014 Ukraine lost part of its territory with no chances of ever getting it back. Hardly anyone will dare speculate that some future events may force Russia to revise its decision to incorporate Crimea. Apparently, the West is perfectly aware of that, too, as all public discussions about Crimean had died down towards the end of the spring. It is noteworthy that the “Crimean issue” receded in Ukraine itself. On the eve of the Ukrainian presidential election in May 2014 not a single candidate had a clear idea of how to solve the problem apart from standard populist vows to press for the return of the “Ukrainian” land.

Alongside the snowballing economic and political crisis there is another reason why the Crimean issue has lost its relevance. Oddly enough, the separation of Crimea was a far less painful blow on Ukrainian statehood than the processes that began to gain momentum in the continental part of the country in April-May 2014. On May 11, 2014 the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Lugansk people’s republics (DPR and LPR, respectively) held referendums, in which an overwhelming majority of the population voted for independence from Kiev. The process of disintegration spread to Ukraine’s mainland.

Violence has become its important feature. The Ukrainian leadership reacted to the seizure of power in the southeastern regions of the country with a military offensive against the Donetsk and Lugansk rebels. As a result, Kiev’s standoff with the DPR and the LPR caused heavy casualties (including civilian) and the exodus of people from the southeast. Separately, one should take note of the extensive international response to the tragedy with the Malaysian passenger jet downed over the area of hostilities.

It is beyond doubt that the root cause of disintegration processes in Ukraine is the initial differentiation of Ukrainian society. The February 2014 revolution in Kiev and the policies of the new Ukrainian authorities fermented old-time social contradictions, and the inability of the state to ensure security and protect the population from illegal armed squads quite predictably produced a situation where part of that population preferred to reject the services of such a state.

The main conclusion that can be derived with a high degree of probability from the latest developments is that no chance for settling the still internal armed conflict in the current situation is anywhere in sight. There are several reasons for that.

Firstly, both warring parties see diametrically opposed ways out of the existing situation. For the DPR and the LPR the most desirable solution is international recognition of their independence from Kiev, while the leadership in Kiev (any leadership, irrespective of its political likes and dislikes, which is quite significant) will never agree to the recognition of Ukrainian disintegration de jure. Clearly, the probability the conflicting parties may achieve a lasting compromise through peace talks is a priori equal to naught.

Secondly, even if either party to the conflict (Kiev, for instance) succeeds, and the DPR and the LPR armies suffer defeat, no chances of national reconciliation in Ukraine will emerge anyway. Of late, the Ukrainian conflict stopped to be just civil and grew into a popular one, where one of the warring parties no longer associates itself with Ukraine by either of the two parameters. The territorial foundation on which the “united” Ukrainian nation emerged in the early 1990s is crumbling down.

As for the so-called “coercion to peace,” necessary at least as an attempt to achieve reconciliation on Kiev’s terms, it is hardly realistic. In a situation where a large amount of firearms is in the hands of civilian population, taking the military operation to a successful outcome (even if it is possible theoretically) in practice will require a military effort of tremendous scale, which the current authorities cannot afford financially, and which the population under their control will hardly welcome.

It has to be acknowledged that over the past decades Ukraine has gone too fragmented to be able to identify and embark on a common development course. The internal armed conflict is not only an effect of national disintegration, but the cause why that disintegration is gaining momentum. The peoples of Ukraine, in particular, those resident in the opposed eastern and western parts of the country, fundamentally different in terms of cultural and historical background, religion and outlook, are no longer able to find points of agreement in the current unitary state, which is objectively incapable of reconciling the conflicting interests of all social groups.

Thus, towards the end of the summer of 2014 Ukraine found itself if not on the brink of collapse as a nation and as a state, then came very close to the point of no return. With every new day of Kiev’s military standoff with the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Lugansk people’s republics, with ever more lives lost on both sides, the country’s society is getting increasingly polarized and irrevocably split. Its fragments are desperately looking for new supports for their self-identity, where there will be no place for a uniform community of Ukrainian people and its territorial integrity.

ECONOMIC INSOLVENCY

The problem of Ukraine’s economic insolvency, in contrast to territorial disintegration, emerged long before the political crisis of 2014. Economic failures of different sorts became an immutable feature of each successive government. Even with all the semblance of economic stability, Ukraine’s fourth president, Victor Yanukovich, and his team merely camouflaged economic imbalances; and this required ever greater financial resources with each passing year. That was largely the reason why the Ukrainian leadership at the end of 2013 postponed the creation of a free trade zone with the EU, the eventual benefits of which looked rather hazy, particularly in the long term. For this decision Kiev received prompt assistance of $15 billion from Russia.

However, when the power changed hands, the ineffectiveness of Ukraine’s economy grew increasingly evident. In January-July 2014 the gold and foreign exchange reserves slumped by 10 percent, while Kiev’s debt for gas remained unsettled. Had Ukraine paid it in full, the decline would have looked far worse, around 35 percent. In all, over the past three years Ukraine’s reserves dwindled by 58 percent (gas debts excluded), while the state debt climbed. Macroeconomic setbacks multiplied alongside daily problems for each individual and each household. Towards the end of the summer of 2014 the devaluation of the Ukrainian currency had exceeded 50 percent against a background of rocketing prices of energy resources and utility services.

The hopes of the incumbent Ukrainian authorities for financial and economic assistance from their Western partners have proved futile and there will hardly be any change in the future. To maintain socio-economic stability (let alone develop itself) Ukraine will need mammoth funds. A decision to provide such funding would be a political step that Europe, still recovering from the crisis, and the United States, keen to slash public spending, are obviously unprepared to take.

As far as IMF loans and private investment are concerned, drawing them in the current situation would be a great problem. The IMF sets rigid conditions (economic reforms, public spending cuts, etc.). If the government and the president agreed to strictly and systematically observe them, they would surely commit a political suicide. As for private foreign investors, a country overburdened with a political crisis, an internal armed conflict and the risk of decay is hardly attractive.

The aggravation of relations with Russia is another heavy blow on the Ukrainian economy. Alongside Russia’s eventual refusal to extend the $15-billion loan and its unpreparedness to offer big discounts off the price of natural gas, Moscow has also imposed trade sanctions against Ukrainian producers, for whom Russia is the main market.

So, the essential distinguishing feature of 2014 is a new spiral of crisis for the Ukrainian economic model, which upsets the government’s efforts to put the country on the track of extensive, let alone intensive, development

However, although this is a long-standing problem, its role in the current crisis of Ukrainian statehood has not fully manifested itself yet. On the one hand, this is due to the high level of the shadow economy, which allows for minimizing the effects of economic failures. On the other hand, in spring and summer seasons many economic problems faced by the population are somewhat smoothed over by backyard farming and gardening, thereby defusing massive discontent.

And still, Ukraine’s economic insolvency may breed more disintegration threats in the near future.

First, Kiev already lacks the financial resources to end the armed conflict in the southeast in its favor. One has the impression that the longer the conflict lasts, the firmer is the resistance from the volunteer corps in Donetsk and Lugansk. This puts a big question mark over the ability of the country’s leadership to respond to the existing and potential military threats, including the spread of firearms and the emergence of illegal armed groups even in the territory under Kiev’s control.

Second, the closer the winter, the greater the risk of a surge in public protests. The “February Revolution” enjoyed support from a majority of the population, as the struggle against a corrupt regime was its catchword. However, if this struggle entails a further decline in the living standards, the public opinion may change again and get more radicalized. Economic insolvency may bring about still greater polarization and growth of mutual intolerance inside Ukrainian society within a matter of months.

Will it be right to say that Ukraine’s economic insolvency is past the point of no return? Most probably yes, and that happened a long time ago. The problem is rooted in the deficiency of the country’s political and economic system that took shape in the early days of Ukrainian sovereignty. Oligarchic capitalism, i.e. the convergence of politics and the economy, placed the interests of big business at the top of political priorities. Naturally, it would be unreasonable to expect that the state of affairs, which has lasted for two decades, would change overnight with the current state system intact.

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL CHAOS

Social unrest, protests, lack of coordination and political havoc are invariable consequences of a revolutionary redistribution of power. Ukraine’s problem is that this redistribution continued nonstop for the past decade. In 2004 Ukraine’s third president was elected under the pressure of the Orange Revolution in a third election round, although such a possibility was not envisaged in the constitution. Later, up until 2010 there followed a long succession of government reshuffles and early parliamentary elections. Lastly, at the end of 2013 and the beginning of 2014 Ukraine’s fourth president was removed from power in an unconstitutional way and the split of the country’s population along geographic and ideological lines had reached its peak.

What makes the current revolution so special is that it has triggered social and political chaos without creating conditions for overcoming it.

On the one hand, there is an imbalance of political forces. Historically, the West-leaning forces were counterbalanced by the centrists. This is precisely the reason why, despite the legally enshrined course towards Euro-Atlantic integration, Kiev for a long time avoided taking any epoch-making moves either towards the European Union or towards NATO. In recent years the Ukrainian authorities, while moving closer towards Europe, invariably made proportionate steps towards Russia. When it became clear that this double-vectored rapprochement had no chance to succeed, Kiev gave up the idea of association with the EU.

When the “February Revolution” caused President Victor Yanukovich to flee the country and the Party of Regions faction in the Ukrainian parliament to fall apart (with some of its members quitting the party altogether), the balance of political forces was upset. The country’s new leadership gained a free hand to push ahead with its own policy. The association agreement concluded with the European Union was one of its main results.

However, the further march of events indicated that the new policy by no means reflected the interests of the whole country. Attempts to dictate a certain vision of Ukraine’s further development, combined with an aggressive propaganda campaign (including anti-Russian) and pressures on political dissent (the motion to outlaw the Communist Party of Ukraine) instantly evoked angry protests from a considerable part of Ukrainian society. In other words, the political superstructure in Ukraine refused to abide by the interests of the social base, which caused a crisis in the relationship between society and the authorities and between different social groups.

On the other hand, stubborn resistance by the new authorities to restore the balance of forces in Ukraine’s political system pretty soon upset their own political unity. Ousting Yanukovich from office and declaring a drift towards Europe was the sole temporary consensus of the reformatted elites, but when it came to deciding on the country’s further development strategy, the initial unity started waning.

As a result, even in the summer of 2014 the Ukrainian authorities still lacked a realistic plan for handling any of the aforesaid problems. As for social chaos, they did nothing to ease tensions; moreover, they went ahead with a biased one-sided policy and a media campaign in its support, thereby driving a wedge into already split Ukrainian society still deeper.

Strange as it may seem, just six months after the “February Revolution” Ukraine saw the emergence of the classical revolutionary situation. The politicians at the top, although having all conceivable powers in their hands, are unable to resolve old-time problems, which in 2014 turned from bad to worse, or at least to restore the level of stability of the previous years. At the grassroots level, society is getting ever more disillusioned with the new authorities. Some criticize them for being too soft and indecisive, while others claim the authorities’ actions are disproportionately harsh. Criticism of the current ineffective policies is possibly one of the few things that still unite the Ukrainian population.

The window of opportunity for improving the Ukrainian socio-political environment still remains open. Early parliamentary elections will allow for adjusting the political superstructure to society’s needs. Partial decentralization of power, which the new leadership has promised all along but not translated into life to this day, might have certain positive effects.

However, these measures will merely help mitigate social and political problems, but not provide a solution to them. It is quite obvious that neither parliamentary elections nor partial decentralization will be able to return the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Lugansk People’s Republic to the fold of the Ukrainian political system. Nor will they eliminate the political vacuum that emerged when some centrist political forces quit that system of their own accord and others were deliberately ousted from it. To overcome the current systemic crisis, the country needs far more radical changes and a profound reform of the government.

HOW TO ACHIEVE “E PLURIBUS UNUM”?

Ukraine today has three systemic problems: national and territorial disintegration, economic insolvency, and social and political chaos. Their further aggravation is fraught with a major threat to stability and to the very existence of the Ukrainian state.

What makes the solution of these problems so complicated is that it requires a comprehensive approach. This means that none of the aforesaid problems can be effectively dealt with separately from the others. It is obvious that encouraging economic growth and restoring national unity will be impossible amid political chaos. Similarly, without ensuring economic solvency one can hardly expect long-term political stability, and without reconciling the radically-minded nationalist west with the separatist southeast, the country’s attractiveness to domestic and foreign investors is doubtful.

The very instance of the 2014 crisis indicates that Ukraine lacks an effective mechanism to deal with internal problems. Ukraine’s current state system is the chief obstruction to development and to the start of a dialogue of all with all on each of these problems. At a time when the Ukrainian population is fundamentally split on many vital issues, the system of unitary state governance, encumbered with exorbitant corruption and convergence of political and economic groups, turns the search for a national compromise into behind-the-scenes bargaining. Such deals can only suit part of society and cause strong rejection from the rest.

In this context, 2014 saw the peak of injustice in state affairs. Using pseudo-democratic rhetoric and mass media propaganda, the country’s interim government replaced the opinion of a majority by a dictatorship of the minority. Making decisions on behalf of all Ukrainian citizens, it started to revise the status of the Russian language and proceeded with European integration course. A short while later the newly elected president put his signature on behalf of all Ukrainians (including the residents of the self-proclaimed DPR and LPR) to an agreement of association with the European Union, although at the beginning of 2014 less than half of all Ukrainians supported that step, and in May 2014 most residents of the country’s southern and eastern regions came out against integration with the EU (http://www.dif.org.ua/ua/polls/2014_polls/mlvbkrfgbkprhkprtkp.htm http://www.razumkov.org.ua/ukr/poll.php?poll_id=865). In addition, after the deposition of Ukraine’s legitimate president a considerable share of the population lost representation in the legislative and executive bodies of power.

Impossibility for society to champion its interests at the state level and the government’s inability to independently and effectively address national issues has brought to the fore the demand for a new state system that would accommodate the diverse opinions. It is noteworthy that the need for such reforms of governance is recognized by all parties concerned, including outside actors. How deep the transformations can and must go is a great controversy, though.

As it has been observed more than once over the years of Ukrainian independence, Kiev’s stance is confined to taking the minimum steps possible and simulating them, rather than implementing them in earnest. The amendments to Ukraine’s constitution proposed by the new president preserve the principle of centralization with regard to some issues, and are quite hazy with regard to others, and thereby dismiss the possibility of a genuine handover of powers to regions.

Kiev’s main opponents, the DPR and the LPR, on the contrary, seek full revision of Ukraine’s state system. They do not rule out some form of association with other regions, but at the same time point out that this may be possible only on new principles and outside of today’s Ukrainian state, in other words, only after their recognition as full-fledged actors of international relations.

Obviously, the latter option is utterly unacceptable for Ukraine if it intends to further exist within its current territorial borders. But that does not mean that the reforms proposed by Kiev will ensure an end to the country’s disintegration. All these reforms can do is create the minimal conditions for eliminating problems in some indefinite future. Today, they merely cover up old-time contradictions, and very unsuccessfully.

In a different situation these first steps would be enough for the national consciousness to evolve into something more united, to make politicians more responsible, and economic growth, stable and intensive. But in the case of today’s Ukraine, whose problems have climaxed and are threatening to exclude it from the historical process for long (possibly, forever), there is no more time left to contemplate and wait, especially in absence guarantees of success.

Ukraine needs deeper structural reforms. Many politicians and political analysts believe that federalization may provide a solution. It is unlikely to solve economic problems overnight, but it might create fundamental prerequisites for that. First, the idea of federalization, if proposed by Kiev, would serve as the basis for preventing Ukraine’s further disintegration and ensure tangible progress towards regions’ reconciliation and unification. Second, federalization would help achieve political and social stabilization, by restoring the balance of political forces on a national scale, and leaving the possibility of addressing all local problems at the regional level.

However, despite the obvious advantages of this option, the current authorities in Kiev, enjoying a carte blanche in shaping state policies, are reluctant to share powers with the regions. Ukraine’s foreign partners show little insistence on that score. Moscow, which proposed Ukraine’s federalization at the beginning of 2014, no longer raises this issue. Brussels does not discuss the idea of federalization at all, being aware that this would mean Ukraine’s far more reserved attitude to European integration, and, consequently, a defeat of European institutionalism in Eastern Europe.

So, since inside Ukraine no parties to the conflict are able to compromise and Kiev itself is unable to dictate its own vision of the country’s development (or enforce that development), the very existence of that country depends on coordination between Russia and the European Union on the issue of Ukraine’s structural reforms. Without external pressures the Ukrainian leadership will go ahead with a policy of palliatives, which at best will camouflage the authorities’ ineffectiveness and society’s split, and only postpone the country’s breakup for some time. Under all other scenarios the decay process in all likelihood will become irreversible and get out of control.

* * *

Ukraine within its current borders has proved too heterogeneous, and society’s post-Soviet transformation too “multi-speed” to develop positively within the borders of an integral unitary state. The 2014 crisis has convincingly confirmed that: it highlighted the existing problems and even aggravated them further.

By and large, Ukraine has been demonstrating all features of a failed state, and the risk of its eventual collapse is rather high. It is well known what the outcome may be of situations where the upper classes are unable to govern the old way and the lower classes refuse to carry on the old way. To prevent such an outcome, Kiev should promptly address three fundamental issues: national and territorial disintegration, economic insolvency and socio-political chaos. Otherwise Ukraine may drop out of the historical process for an indefinite period of time.

At this point one cannot say yet that Ukraine has passed the point of no return and is heading towards disintegration. There still exists a theoretical possibility of taking on sweeping structural reforms that would allow for prompt recovery from the socio-political crisis. At the very top of the list of such reforms is the long standing issue of the country’s federalization.

However, despite such a possibility Kiev has voiced a clear message that it is reluctant to delegate powers to regions of its own free will. As a result, a stalemate situation has emerged, in which Kiev’s new authorities are unable to address the problems that deteriorated after their rise to power, while at the same time showing no intention to take the steps that have no alternative.

Kiev is incapable and reluctant to cope with the crisis on its own. Hence the sole chance for Ukraine to retain its statehood, albeit in a changed format, will emerge if the Ukrainian authorities are pressed for reforms from the outside. This implies achieving a certain compromise over Ukraine by Russia and the European Union, as the main regional centers of power whose relations have already suffered great harm due to that country’s internal problems.

It remains to be seen how far Moscow and Brussels will be prepared to go and how many political ambitions their leaders will be prepared to sacrifice to give Ukrainian statehood another chance. Considering the long string of problems that Russia and the EU have had in relations with Ukraine over the past two decades, including the latest adverse effects on Russian-European cooperation, one has to admit that the chances are slim.