THE SITUATION ON THE INTERNATIONAL OIL AND GAS MARKETS

Despite some very pessimistic forecasts concerning the prospects

of the oil industry, the role of hydrocarbons in the development of

the world economy will continue to be decisive for another several

decades.

The energy security of the highly developed countries will

depend on the availability of reliable hydrocarbon sources. These

countries are the main oil consumers, whereas a small group of

developing and transitional states are largely responsible for the

export-oriented oil production. The United States, for example,

accounts for 25.4 percent of the world’s oil consumption and a mere

9.9 percent of the world’s oil output. The developed countries of

Northeast Asia (Japan, South Korea and Taiwan) do not produce oil,

but they consume 11 percent of the global oil supply. After 1993,

fast-developing China joined the group of net importers and now

consumes 7.4 percent of the world’s oil (together with Hong Kong),

while extracting 4.8 percent of the world’s total oil output.

The Middle East, the world’s leading oil exporter, extracts 28.5

percent of global oil supplies, but consumes only 5.9 percent.

Russia follows right behind with 10.7 percent of the world’s oil

output, but it consumes even less oil than the Middle East with 3.5

percent.

Not that long ago, oil replaced coal as the world’s main source

of energy. Now we are witnessing the beginning of a new era when

natural gas will replace oil. Energy production from oil pollutes

the environment two times less than peat or coal, but natural gas

is three times environmentally cleaner than oil. However, natural

gas will overtake oil as the world’s primary energy source only

after the process of turning gas into a global commodity gains

momentum.

Although natural gas is a relatively new commodity on the local

and international markets, it is already obvious that it is

characterized by the same geographical disproportion between

production and consumption, as is characteristic of oil. The United

States, for example, is one of the world’s two top leaders in gas

production (21.7 percent of the world’s output), but it consumes

more than it produces (26.3 percent); the consumption and,

consequently, the import of gas by the U.S., keeps steadily

increasing (actually all newly built electric power plants in the

country use natural gas). The 15 older members of the European

Union depend on natural gas imports even more – they consume 15.2

percent of the world’s gas output, although they produce only 8.3

percent of the world’s total amount. Considering the depletion of

Europe’s own gas resources, its reorientation toward natural gas,

and the increasing convergence of its gas and power-engineering

sectors, Europe’s dependence on gas imports will continue to grow

at a slow but steady pace.

The developed countries in Northeast Asia fully depend on the

import of liquefied natural gas in the same way they depend on oil

imports. For example, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan consume 4.4

percent of the world’s output. China in 2002 produced and consumed

equal amounts of natural gas (1.3 percent together with Hong Kong).

However, fast economic growth, together with the conclusion of

long-term contracts for gas supplies, are turning China into a net

importer.

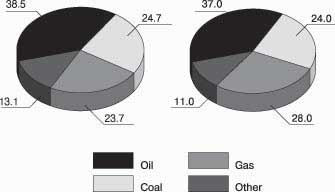

World energy balance (%)

Russia far outpaces other countries in the production and export

of natural gas; it accounts for 22 percent of the world’s gas

production. And although its domestic gas consumption stands at

15.3 percent of the world’s figure (ranking second after the U.S.),

its export potential (the difference between extraction and

consumption) exceeds the aggregate export potential of three

regions in the world – the Middle East, Africa and Latin America.

In 2002, the Middle East produced 9.3 percent of the world’s gas

and consumed 8.1 percent. The main producer – Saudi Arabia –

consumes all the natural gas that it extracts, while Iran consumes

slightly more gas than it produces. Until recently, only Qatar and

the United Arab Emirates enjoyed a natural gas surplus, which they

sold to neighboring countries. The export potential of Africa is

somewhat higher, but only due to Algeria. In the Asia-Pacific

Region, three countries boast the largest export potential –

Indonesia, Malaysia and Australia (6.2 percent against 3.4

percent).

Now let us examine how export hydrocarbon resources are

distributed among their major consumers.

In 2002, Western Europe as a whole was the main importer of oil and

related products. The bulk of these imports came from three

regions: Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (214.6

million tons), the Middle East (161.1 million tons), and North

Africa (122.5 million tons). Europe is demonstrating an increased

interest in the African continent, which seems to be part of a

strategy for diversifying its oil import sources there. In the last

few years – especially during the presidency of George W. Bush –

Europe has faced bitter, even aggressive, competition in the region

from U.S. corporations.

The U.S. accounts for 26 percent of all imports of oil and

related products (561 million tons), but the Americans eventually

formed a diversified structure for their imports. The greatest

amount of oil and related products (171.7 million tons) are

imported from Canada and Mexico – Washington’s partners in the

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). South and Central

America account for 119.2 million tons of oil shipments to the

U.S., while Africa accounts for 69.1 million tons. Europe provides

57.0 million tons; Russia and the CIS, 9.8 million tons;

Asian-Pacific Region, 12.8 million tons; the Middle East, 114.7

million tons. Through such a strategy, the U.S. has protected

itself against catastrophic developments, for example, in the

Middle East. Furthermore, unlike Europe, the U.S. has ‘alternative’

oil and gas reserve fields in Alaska, although development in this

sensitive region remains blocked by U.S. legislators. However, the

U.S. government could easily overcome this resistance should an

emergency situation arise with regard to the global energy

supply.

Of the total amount of oil and related products exported from

the Middle East countries, 62.3 percent goes to the Asia-Pacific

Region. For example, Japan released figures for the year 2003

demonstrating that its import of crude oil supplies from the Middle

East was 87 percent.

The global situation with regard to natural gas supplies is

somewhat different. Presently, natural gas is transported largely

by pipelines, which reduces the distribution of this commodity to

the regional level. The amount of liquefied natural gas being

transferred by sea has not been very substantial: in 2002, the

figure stood at 150 billion cubic meters, compared with 431.35

billion cubic meters of gas transported to the global markets via

pipelines.

Table 1. Oil

| Oil importers |

Percentage of world consumption |

Percentage of world production |

| The United States | 25.4 | 9.9 |

| Western Europe | 19.3 | 7.7 (Norway) |

| Northeast Asia | 11.0 | 0.0 |

| China (including Hong Kong) |

7.4 | 4.8 |

| Oil exporters |

||

| Middle East | 5.9 | 28.5 |

| Russia | 3.5 | 10.7 |

| Africa | 3.4 | 10.6 |

| Central and South America |

6.1 | 9.4 |

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

June 2003. BP p.l.c., L., 2003.

The bulk of liquefied natural gas is consumed by countries in

Northeast Asia (Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) – 103.8 billion

cubic meters. Western Europe consumes slightly more than 39 billion

cubic meters, while the U.S. (including Puerto Rico) consumes more

than 7.1 billion cubic meters. The dependence of global consumers

of liquefied natural gas on supplies from the Middle East is much

less. Although there have been signed contracts for gas exports in

the region, it will be several years before the development of gas

production begins there. Presently, the export of liquefied natural

gas from the Middle East slightly exceeds 33 billion cubic meters.

The largest suppliers of liquefied natural gas are the

Asian-Pacific countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia and Brunei)

which provide over 74 billion cubic meters; African countries, such

as Algeria, Nigeria and Libya provide 35.35 billion cubic

meters.

The largest consumer of natural gas is Western Europe; it imports

240 billion cubic meters. The main suppliers of natural gas to

Europe (including Central and Eastern Europe) are Russia (128.2

billion cubic meters) and Algeria (29.38 billion cubic meters);

Algeria also supplies 26.13 billion cubic meters of liquefied

natural gas. The second largest importer of natural gas is the

United States which imports 109 billion cubic meters of gas from

Canada.

Table 2. Natural gas

Proven oil reserver (% of world reserves)

| North America (NAFTA) | 4.6 |

| Europe | 2.9 |

| Russia | over 30 |

| CIS (Central Asia) | 3.7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 4.1 |

| Iran | 14.8 |

| Qatar | 9.2 |

| UAE | 3.9 |

| Africa | 7.6 |

| Central and South America |

4.5 |

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

June 2003. BP p.l.c., L., 2003.

To assess the prospects for the development of the global oil

and gas markets, one must take into consideration one more factor:

the amount of resources that the hydrocarbon-producing countries

possess, together with their ability to maintain the current

consumption levels, as well as its predicted growth. The Middle

East now boasts the largest proven oil reserves: in 2002, they were

estimated at 685.6 billion barrels, or 65.4 percent of the world’s

oil reserves. Provided that oil extraction is maintained at its

present level, the oil reserves will last for another 92 years.

Saudi Arabia alone can exploit its oil reserves, which comprises 25

percent of all oil in the world, for the next 86 years.

For the short and even medium term, however, the Middle East

will remain the most unstable region in the world – a large

‘medieval island’ in an ocean of fast-developing industrial and

post-industrial economies. The problem for the Middle East is not

only the nature of its political regimes, but the socio-economic

nature of the society. The problem cannot be solved by sending

U.S., NATO or UN armed forces into the region. This is the reason

why, perhaps, a majority of developed countries have begun

searching for alternative sources of hydrocarbon resources.

South and Central America can alleviate the situation for a

short period of time, and only for the U.S. Africa has even less

proven reserves, and these will last for only 27.3 years if

extraction is maintained at the present rate. The situation is

worse in the Asia-Pacific Region where hydrocarbon reserves will be

depleted within 10 to 14 years. In Europe and the CIS, the largest

proven oil reserves are in Russia; these will last for less than 22

years. Norway, ranked second in Europe for oil reserves, is far

behind Russia with one percent of the world’s proven reserves. All

of the other countries in Europe and the CIS, some of which are

often cited in the press and even in scientific studies as

potential alternatives (e.g. Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan), each

possess less than one percent of the world’s reserves. These

factors make it obvious that all of the talk about the West’s

desire (especially in the U.S.) to establish democracy in the

Middle East is just a smoke screen, and a rather transparent one,

which cannot conceal the true motive – their interest in the Middle

East’s oil reserves. (The Americans, for example, did not hesitate

to establish close relations with the harsh dictatorship in

Equatorial Guinea as soon as large oil reserves were discovered

there.)

Russia is an indisputable leader in proven natural gas reserves

with over 30 percent of the world’s total amount. If Russia

continues extracting gas at the present rate, its reserves will

last for more than 80 years. By comparison, the other countries in

Europe and the CIS, taken together as a whole, account for only 8.7

percent of the world’s reserves. Norway’s reserves may last for

33.5 years, while gas fields in Britain may be depleted in less

than seven years. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan together

possess 3.7 percent of the world’s natural gas reserves, but only

Kazakhstan can exploit its gas fields for another 100 years or

longer. In any case, all the above countries can only meet Europe’s

short-term natural gas requirements. In the long term, Russia has

no serious rivals when it comes to natural gas reserves.

Russia is far ahead of second-place Iran, which possesses 14.8

percent of the world’s gas reserves. Iran’s natural gas supplies

will last for at least 100 years. However, political considerations

have caused Western corporations to set their sights on Qatar with

its 9.2 percent of the world’s gas reserves; these are expected to

last as long as Iran’s reserves. Another Middle East country

attractive to foreign consumers is the United Arab Emirates (3.9

percent of the world’s gas reserves), whereas Saudi Arabia (4.1

percent) consumes all of its natural gas reserves itself.

In Africa, only Algeria, Nigeria and Egypt have large, proven

gas reserves. In Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia – major exporters of

liquefied natural gas to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan – have only

1.7 and 1.4 percent of the world’s gas reserves, respectively,

which will last for 37 and 42 years, respectively.

In North America, the situation with its proven reserves of natural

gas is similar to that with its oil reserves. The three NAFTA

member countries account for 4.6 percent of the world’s reserves,

which will be enough for 9.4 years. Neighboring countries in

Central and South America (4.5 percent of the world’s reserves)

will hardly be of much help to them. Gas reserves in Central and

South America may last for 68 years, but this gas will more than

likely be used to meet the growing regional demand. The small

country of Trinidad and Tobago may be the only exception. Although

it has only 0.4 percent of the world’s gas reserves, this amount

far exceeds the country’s domestic needs. The U.S. has already

concluded several contracts with it for supplies of liquefied

natural gas.

So, America, together with the large corporations representing

its ‘gas interests,’ will offer bitter competition to the West

European and Northeast Asian countries within the international gas

markets. This factor, in addition to the fast-growing demand for

hydrocarbons in China, suggests that Russia will play an ever

growing role in ensuring a normal balance between supply and demand

on the world’s natural gas market.

MERGERS AND TAKEOVERS

Changes on the world energy markets, and the toughening of

environmental requirements in the Western countries, forced the

international oil and gas companies to take appropriate measures.

These factors also prompted the EU leadership to draw up specific

electricity and gas directives.

The problem of dwindling oil reserves, together with dropping

oil prices in the mid-1980s, and again in 1997-1999, provoked

several waves of mergers and takeovers within the oil and gas

industries. During the first wave, Texaco took over Getty Oil,

while Chevron took over Gulf Oil. The second wave was characterized

by a series of strategic mergers and takeovers: British Petroleum

took over Amoco, and then eventually ARCO. This was followed by

Exxon taking over Mobil Oil to become the world’s largest oil and

gas corporation. These heavyweights were joined by France’s Total

SA after it took over Elf Aquitaine and Belgium’s Petrofina SA.

Finally, Chevron and Texaco completed the process for their merger.

The strategic goal of these mergers and takeovers was to

consolidate efforts and funds in order to find and develop new oil

and gas reserves in remote regions. These are usually in areas with

harsh natural conditions, or in deep-water fields that are more

difficult to develop.

The new strategy was further prompted by natural gas gradually

becoming a global commodity. This tendency helped to initiate the

‘gasification’ of the heavyweight players, that is, their evolution

from oil corporations into oil-and-gas and, finally, gas-and-oil

corporations. Royal Dutch/Shell Group offers the most glaring

example of this transition. It has the largest share of gas (48

percent) in the overall ratio of its oil and gas resources, and in

the next three to four years the company may finally shift toward

gas. This move would naturally correspond with the contracts the

company has recently concluded, as well as with its officially

proclaimed reorientation toward natural gas (John Barry, named

chairman of Royal Dutch/Shell in Russia, made a statement to this

effect last summer at an annual conference organized by the

Renaissance-Capital Investment Group). Shell is followed by Exxon

Mobil, whose gas reserves are actually equivalent to Shell’s.

However, Exxon Mobil’s gas/oil ratio is slightly different at 45/55

percent. Nevertheless, Exxon Mobil is confidently leading the other

majors in gas production. BP is placed third among the world’s oil

corporations in gas extraction (its oil/gas ratio is 52/48

percent). Also, BP now accounts for 30 percent of the world trade

in liquefied natural gas. Other majors are also beginning to move

in the same direction (for example, Chevron Texaco and

ConocoPhillips).

However, the tectonic shifts on the world energy markets have

been marked by an important new trend in the last few years. The

EU’s adoption of electricity and gas directives in 1996-1998, and

more importantly, the actual start of their implementation, was a

major factor for the new wave of mergers and takeovers in the

world’s energy sector. In 2001-2003, a fundamentally new energy

policy began to take shape in Europe. The EU’s strategic

orientation toward the most environmentally safest fuel – natural

gas – has resulted in the ever-increasing use of gas turbines at

newly built electric power plants. Consequently, this has led to an

increasing convergence in the production and marketing of gas and

electricity.

Recently, the national gas and electricity companies were

confronted with fundamentally new challenges, such as the

liberalization of the energy markets, their greater openness to

third parties and the privatization or commercialization of

state-owned energy corporations. In order not to go bankrupt, or

become easy prey for a takeover by other companies, the national

corporations had to adapt to the new situation and meet those

challenges. The national European corporations had to be

consolidated and made more competitive before they entered the

world energy markets. As it turned out, the antimonopoly

requirements set by the Brussels officials often motivated the

national energy companies to restructure and extend their

businesses by exceeding the national frameworks. This was

accomplished through diversification, or the convergence of the gas

and electricity sectors.

At the same time, and irrespective of these European tendencies,

the United States experienced a negative situation that was

provoked by the unsuccessful deregulation of its gas industry. What

evolved was an energy crisis in California, and the collapse of

several energy corporations, among them the huge Enron company.

These events prevented American businesses from taking an active

part in the third wave of mergers and takeovers which had already

begun in Europe. As a result, the assets of Enron, El Paso and

other energy companies continue to be sold, and are being purchased

by independent U.S. oil companies. In other words, the energy

business in the U.S. is being restructured, but there is a

‘European’ nature to the third wave of mergers and takeovers.

This wave has resulted in the rapid rise of some national energy

companies in Europe to the majors’ level. Germany’s

super-corporation E.ON AG, which emerged in 2000, provides a prime

example. In the course of the third wave it took over Britain’s

Powergen (only a year before this company had taken over the U.S.

company LG&E Energy), Sweden’s Sydkraft, Britain’s TXU Europe

Group, and U.S.-owned Midlands Electricity in Britain. However,

E.ON AG’s main transaction in 2002-2003 was its merger with

Germany’s Ruhrgas, which took a year and a half to finalize. It was

necessary for E.ON AG to overcome strong resistance from the local

authorities, Brussels regulatory bodies, as well as its German and

European rivals. Finally, under the slogan of Germany’s “national

energy security,” E.ON AG established a full-fledged, vertically

integrated corporation that is capable of successfully competing on

the European and global markets. This was a blow to Brussels

bureaucracy which had fought for many years to divide the functions

and businesses of the national energy companies.

Another blow to the EU’s energy liberalization strategy hit the

very heart of the liberalization process, and in the most exemplary

country in this respect – Great Britain. The previous policy of

splitting businesses, as well as destroying the monopoly of the

vertically integrated British Gas Corporation, only weakened the

British positions. This is why, in the course of the third wave,

British companies were consistently the victims of takeovers. The

only exception among the major transactions between 2001 and 2003

was the merger of the gas distributor Lattice Group and the

electricity transmission company National Grid Group. But this

intra-British transaction only emphasized the failure of all

previous efforts to demonopolize the energy sector in the

country.

Throughout this period, companies merged and took each other

over en masse. This process involved the national oil, gas and

electricity companies from various countries (German, French,

Spanish, Italian and so on). This gigantic restructuring of the

European energy sector is not yet over. However, many experts now

conclude that this wave of mergers and takeovers will result in an

increase in regional monopolization, together with the formation of

an oligopolistic structure of the global energy market. Its main

actors will comprise several traditional majors, plus three to five

newly established European super actors with global ambitions.

WHAT THE WEST WANTS FROM RUSSIA

The energy majors’ strong interest in Russia is easily

explainable. Today, these companies own a total of almost six

percent of the world’s oil reserves that are concentrated in the

more developed and ‘ripe’ oil fields. According to the Oil and Gas

Journal, the largest five majors now control only 15 percent of the

oil and gas markets, and all of them must address the problem of

decreased production, as well as geopolitical and geo-economic

risks from OPEC. At first, the majors tried to apply the mechanism

of production-sharing agreements (PSA) in Russia. In the 1960s,

Indonesia concluded production-sharing agreements with relatively

small independent oil companies from the West (above all, the

U.S.); this practice was followed by several other countries. These

agreements served as ‘rams’ for destroying the world monopoly of

the ‘Seven Sisters’ – the past companies which made up the majors.

Later it was the majors who sought the rights to PSA for gaining

access to Russia’s oil and gas wealth.

However, the imperfection of Russian laws impeded PSA

implementation. It was only after the government of Yevgeny

Primakov got through the State Duma 22 amendments to the law (in a

one-week period of time) that the first (Sakhalin) agreements were

put into effect. Later, however, some Russian oligarchs (above all,

those who had no roots in the oil business and who viewed it as

another field for speculative financial operations) launched

another massive PR campaign against PSA in the press and inside of

the State Duma under pseudo-patriotic slogans, accusing the

government of ‘selling out the Homeland.’ However, the majors soon

realized that the true reason for the fierce resistance to PSA in

Russia was not the rejection of foreign capital per se, but the

fact that there was no room for speculative oligarchs in the

state-majors link of the PSA mechanism.

The oligarchs began to bargain with the majors, and offer

themselves as partners in future joint ventures. This was possible

since they had successfully blocked PSA. Furthermore, they had

successfully acquired numerous licenses to develop oil and gas

fields, but were unable to do this on their own. As a result, the

majors were offered a Russian variant of a merger, which was

different from those described above. It was proposed that a

foreign company would not fully merge with a Russian company in

order to create a new joint venture, but would only merge its

Russian assets into it. For the same reason, unlike PSA, such

transactions cannot be described as direct investment. For example,

the funds that the majors put up are simply pocketed by the Russian

owners. Unfortunately, no one knows where this money will be later

invested.

Brussels also has a strong tendency to view Russia as a source

of cheap hydrocarbons, but here the emphasis was placed on natural

gas. The EU’s gas directive was prepared and adopted without the

participation of the main natural gas suppliers, nor without taking

their interests into consideration. This was done in order to

introduce the spot market mechanism around the world, as well as

destroy the system of long-term contracts which has been the only

reliable basis for energy cooperation between Russia and the EU. It

has also been a solid guarantee of the energy security of the EU

member states themselves. Later, however, realism prevailed;

furthermore, the energy crisis in California, together with

Britain’s failed deregulated system, apparently served as good

lessons.

Russia and the EU have now reached a more or less acceptable

compromise on long-term contracts. Yet, the two parties are still

far away from a comprehensive solution to the gas problem. The

European Union fully ignores the obvious fact that gas is Russia’s

natural competitive edge. It demands that Russia raise its domestic

gas prices, thus interfering in its internal affairs. The EU hopes

that this move will reduce the price of exported gas; it does not

care that an increase in domestic gas prices would bring the

Russian economy to its knees. Furthermore, such a move would hurt

the Russian population, a majority of which already lives on the

verge of poverty. Furthermore, the West has repeatedly given Russia

rather dubious recommendations that it should liberalize its gas

sector and break up Gazprom. Interestingly, this pressure is being

made amidst the aforementioned process of takeovers and mergers

that are occurring throughout Europe, together with the formation

of large, vertically integrated corporations.

WHAT RUSSIA WANTS FROM THE WEST

Representatives of the developed countries have repeatedly

stated that the West is interested in a strong Russia. However,

these declarations are at variance with the practices of many

leading states. When in the last few years Russia began to

establish order in its economy, and work out a strategy for its

economic development that corresponded with its national interests,

the U.S. and the EU immediately grew cold toward it. The same thing

occurred when Russia attempted to implement this strategy in order

to prevent the uncontrolled embezzlement of its natural

resources.

The Expert magazine, in a February issue, made the following

fair remark: “The present coolness in relations between Brussels

and Moscow was caused by the failure of Europe’s strategy which the

EU had hoped would have created a weak Russia.” Apparently, the

West cannot tolerate the idea that the epoch of Boris Yeltsin’s

flabby and pliant authoritarianism (which for some reason is still

persistently described as ‘democracy’) has become a thing of the

past and that from now on Russia will keep upholding its national

interests in a polite yet rigid way. In February 2004, Russia’s

foreign minister pointed out that someone “deliberately or not, is

leading us away from the strategic long-term tasks, the

accomplishment of which we must focus our main efforts on” (quoted

from Germany’s Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung).

It is true that the Russian economy is not operating at its full

potential, and the country is faced with a major dual task:

optimizing and modernizing the industrial sector and,

simultaneously, laying the foundation for a new IT or

post-industrial environment. This is why Moscow is very interested

in developing its energy cooperation with the West. However, this

cooperation should not result in Russia becoming a raw-materials

appendage of the West, as it was in the 1990s. (Norway avoided this

fate by pursuing a prudent economic strategy.) This cooperation

must be built on a mutually advantageous and equitable basis. The

parties must take into consideration each other’s interests,

although they may not fully coincide: the West’s interest in

reliable and stable supplies to ensure its energy security, and

Russia’s interest in developing its economy and improving the

well-being of its population.

Russia has been making active efforts to fulfill its

contribution to this cooperation. In the last few years, it has

been stepping up the production and export of oil and natural gas.

In 2003, oil output increased to 421 million tons, compared to 379

million tons in 2002. According to expert estimates from the UBS

Investment Bank and Brunswick UBS, oil output will reach 457

million tons in 2004, and 568 million tons by 2008. And although

Russia will hardly repeat its 2003 record-high growth rate (11

percent) in oil production in the near future, even the 4.8 percent

increase in the absolute physical volume, planned for 2008, will

still be a high figure, especially as the expected increase in oil

exports will be 50 to 100 percent higher than the production growth

rate. In 2003, Russia exported 4,259,000 barrels a day. According

to the Oil and Gas Journal, in 2008 this figure may reach

6,648,000.

Russia has been consistently removing the bottlenecks in the oil

transportation system. The Transneft Corporation, for example, is

successfully completing the construction of the Baltic Pipeline

System with a terminal in Primorsk. According to the 2002 plan, its

throughput capacity was expected to reach 18 million tons of oil.

Last year, the oil output was increased to 30 million tons, and in

2004, the system’s capacity will be further increased to 42 million

tons. By 2005, this figure will reach 50 million tons. Other

Russian companies, such as LUKoil, Surgutneftegaz and Rosneft, are

also building oil terminals along the Baltic coast. An application

for the construction of another oil terminal was submitted by

TNK-BP and approved in February 2004.

The production of natural gas in Russia has been growing as

well: in 2003, it amounted to 2,053 billion cubic meters.

Russia has markedly increased gas exports to Western and Central

Europe: in 2002, this figure stood at 128.6 billion cubic meters,

while in 2003, the figure increased to 132.9 billion cubic meters.

However, problems continue to hinder further progress. For example,

there has been the reoccurrence of illegal gas siphoning from

Russian pipelines that travel through neighboring CIS countries.

This has forced Russia to take measures in order to ensure the

uninterrupted flow of gas supplies to Europe. Gazprom and Finland’s

Fortum, for example, will conduct a feasibility study for the

construction of a 5.7-billion-dollar North European gas pipeline

that will bypass all intermediate countries on the way to Europe.

The proposed pipeline will be built on the seabed to the German

coast, and there are plans for it to extend to Britain as well. The

first phase of the project is planned to be completed in 2007.

By the end of 2004, Gazprom will complete the construction of a

gas pipeline from Yamal to Europe; the pipeline travels via Belarus

and will be the sole property of the Russian company. Finally,

within the framework of a Russian-Ukrainian consortium that was

established in October 2002, Gazprom has prepared two variants of a

feasibility study for the construction of another gas pipeline.

This one is planned to transport gas from Russia and Central Asia

into Western and Central Europe.

Russia’s efforts in the realm of energy production do not rule

out the participation of foreign capital in large-scale energy

projects. On the other hand, Russia is now taking another look at

its position concerning the activities of foreign companies in the

country. As a result, it is likely that Russia will discourage

speculation on the energy market, together with the unauthorized

large-scale strategic (the word ‘strategic’ seems unnecessary here)

transactions which are damaging Russia’s national interests.

However, direct foreign investment that is used for locating and

developing new oil and gas fields, together with outside

participation in the construction of new pipelines, will only be

welcome.