The full Russian version of the article was published in Rossiisky Vneshneekonomichesky Vestnik, No.6, 2010.

Over the almost twenty years that have passed since the establishment of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), all its member countries, including Russia, have gone a difficult way of rethinking their future development.

Most importantly, the states have moved from declarations of sovereignty to an understanding of the need to fill it with real economic interests. The task of modernizing national economies has become pressing under the impact of highly negative consequences of the financial and economic crisis and the ensuing new challenges to long-term development. In the absence of modernization, economic growth, if any, brings about not qualitative improvements but low competitiveness even in basic sectors of the economy, heavy dependence on the situation in world commodity markets, soaring inflation, balance of payments deficits, dependence on external sources of funding, and heightened social tensions.

Meanwhile, the fears of neighboring states about a revival of Moscow’s imperial ambitions are fading. Guided by a pragmatic analysis of their interests, the Commonwealth countries see the inevitability of its progressive development under the leadership of Russia. This conclusion is based on two obvious facts. First, no one disputes the sovereign right of our partners, as well as the right of Russia itself, to develop mutually beneficial relations with the outside world, not limited to the former Soviet Union. Second, our economies are closely interrelated, and their combined potential is much more powerful. Also, we have common problems requiring solutions.

WHY THERE IS NO REASONABLE ALTERNATIVE TO INTEGRATION

The basic factor that motivates the CIS countries to integrate is their aggregate resource potential. These countries occupy about one-sixth of the earth’s surface and account for about 5 percent of the world’s population; thus, they control a strategic share of world resources required for economic development. However, they do not use this potential intensively enough. Together they can provide only 3.5 percent of the world’s exports and 2.5 percent of the world’s services.

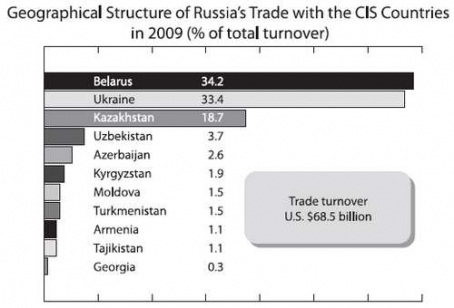

European countries account for more than a half of the CIS’s trade; 20 percent of this trade is done within the CIS (for comparison: in the European Union this figure stands at 40 percent); and 10 percent of CIS exports go to Asia. The decline of the CIS’s internal trade is an obvious trend that characterizes the state of affairs in the Commonwealth.

Against this background, there emerge major alternative projects. China is actively positioning itself in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The European Union has put forward the Eastern Partnership initiative, which is especially interesting for its trade-and-political component providing for the conclusion of free trade agreements with some CIS countries. These and other projects, which do not fit in the logic of the Commonwealth’s long-term development, will gradually weaken the forces consolidating it.

However, the complementarity of the CIS countries as an objective basis for integration is still strong. First of all, this is a unique aggregate potential of natural resources including energy and strategic raw materials for industrial restructuring on the principles of modernization and innovation development.

Considering economic growth prospects and the number of consumers, the CIS countries are potentially one of the largest markets for goods and services. Liberal and predictable conditions of trade in such a market can become an independent factor of stable economic and social development.

The CIS countries can also solve the pressing infrastructure problem facing them – transportation support for the economy, including foreign trade – and thus immediately raise their overall competitive positions in the global market. Each state, taken separately, is strategically vulnerable and its channels of access to world markets are limited; however, things will be quite different if these states pool their efforts.

The CIS countries are for each other a source of investment, innovations and labor migration – these are all key factors of economic growth. Each CIS country, depending on the degree of its integration into the world economy, can attract capital for joint projects, especially if there are legal conditions for that (for example, investment protection or effective dispute settlement procedures). All these countries have innovation development experience since Soviet times and highly qualified workforce.

These largely unique resources are not fully tapped, and their development and commercialization is a long overdue problem. Finally, there is every reason to create a unified labor market within the CIS. The regulation of labor migration flows to Russia could be the first step towards this market. The CIS should also build an integrated employment management system that would address, among others, issues pertaining to wages, social security, pensions and co-management of personnel training.

The formation of an energy policy that would cover the production, processing and transportation of all kinds of energy should be an integral part of the CIS’s development. This issue is very delicate, as it concerns basic issues of national sovereignty and therefore it will take much time to fully coordinate the program. The pace of this work will directly depend on progress in the integration. Therefore, the CIS countries should at first focus on a joint solution of energy efficiency issues and to this end create a system of support for innovative projects in energy, which would provide additional sources of growth in the economy.

I cannot say that the above considerations were ignored when the CIS worked on its strategic plans and methods for their practical implementation. For example, in 2008 the CIS heads of government endorsed The Strategy of CIS Economic Development until 2020, and in 2009 they adopted an action plan for implementing its first phase. These documents for the first time summarized in one format all proposals concerning the possible agenda of a reformed Commonwealth.

A ROAD MAP FOR THE INTEGRATION ROUTE

The rapidly changing situation in the global economy, a growing understanding of the need for joint action to modernize the economy and start innovative development, and the accelerated establishment of the Customs Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan require that the Commonwealth draw up a more compact agenda for top-priority actions that would help achieve concrete results. The agenda should also outline the basic contours of the future CIS as an integration group, as well as stages in its development and relations with external partners. It is only a reform that can help preserve the Commonwealth as an integration group. This is the main task, which can be achieved along two equally important avenues – the consolidation of the free trade regime and the establishment of an integrated economic space.

The CIS should quickly (possibly already in 2010) finalize work on a treaty on the establishment of a multilateral free trade zone in the Commonwealth, where all important issues pertaining to trade policy would be regulated. Importantly, this treaty must be in line with the norms and rules of the multilateral system of trade regulation, which would enable membership in the WTO for the participating states and compatibility with commitments made with regard to third countries – WTO members and associations such as the European Union. The treaty would have the following advantages:

- It will replace dozens of bilateral agreements, which will significantly simplify the administration of intra-regional trade and reduce transaction costs;

- It will introduce a uniform interpretation of terms and procedures;

- It will cover the entire range of issues pertaining to trade regulation (the existing bilateral agreements have not settled some important issues, including the full range of protective measures, subsidies, and restrictions with a view to ensuring the balance of payments);

- It will provide for a mechanism for settling disputes, which would help to effectively resolve trade conflicts;

- It will be open for third countries, which will facilitate the formation of a wide Eurasian zone of cooperation.

The fast conclusion of a free trade treaty would also be important because it would codify the parties’ commitments, acceptable to them today, and show what they will be ready for tomorrow. This is not an idle issue for the CIS countries. The crisis in the global economy hit them the hardest – due to their dependence on commodity markets and external financing. This factor motivates governments to support viable segments of national economies, including through export and other subsidies and import restrictions. The treaty may provide for this kind of restrictive measures through exemptions from the free trade regime, the mitigation of provisions on the abolition of subsidies, and retention of the participating countries’ right to grant preferences to domestic suppliers in government procurement.

At the same time, when determining the content of provisions concerning subsidies, government procurement and competition in general, the parties must understand that these are the key issues which are crucial for companies’ access to markets of other CIS countries on equal and fair terms. The creation of such conditions requires harmonizing technical regulation as well, as technical barriers to trade can be an even tougher instrument of limitation than tariffs and subsidies. If this factor is ignored and if no concrete steps are taken in the sphere of technical regulation, there will be no free circulation of goods. The same refers to sanitary-and-hygienic, veterinary and phytosanitary rules.

Without going into all the provisions of the treaty, let me just say that the treaty should provide for an effective system of dispute resolution as regards its interpretation and application. This goal is served by the establishment of an effective judicial authority, to which the parties’ companies would be able to apply.

Another task is creating an integrated economic space. Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan have made significant progress by establishing a Customs Union between themselves. Now they are working hard to create a legal framework for a Single Economic Space. Moscow views the Customs Union and the Single Economic Space as an opportunity to use the benefits of real integration and show them to its partners. Simultaneously, the parties are trying to lay the foundations for a Eurasian Economic Space. This possibility exists as the Customs Union members (along with Ukraine) make the bulk of a future common market of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

Russia and the other Customs Union members are very interested in the development of integration processes in depth and scope.

The interests of the CIS countries do not coincide in every sphere, but this factor does not stand in the way of their mutual cooperation. At the same time, the realities of global competition require pooling efforts in priority areas that determine the competitiveness and development potential of economies.

Much will depend on the extent the free trade regime will be freed from reservations and exemptions within the framework of a respective treaty. The more the markets are open to each other, the higher the demand for additional economic agreements ensuring the unity of the competitive environment, and the greater the benefits of the implementation of pilot projects. So the task of creating an integrated economic space is divided into two components.

First of all, instruments of economic regulation in the CIS must not run counter to norms of the Single Economic Space. Second, it is necessary to promote sectoral initiatives with concrete tangible results. Thus, the first component deals with norms, while the second, with projects.

The normative component would provide for the creation of elements of an economic union. The latter would guarantee free movement of goods, services, capital and labor. Free movement of goods would be ensured by the Customs Union, as the member countries of the free trade zone have different levels of import duties on goods from third countries, which presupposes internal borders and control over re-exports. Free movement of services, capital and labor would be ensured by separate agreements establishing national regimes in some spheres, and by a number of documents providing for equal competitive conditions.

The Customs Union is now working on a package of agreements which is expected to be adopted not later than early 2012. Attempts to transfer all these accords to the negotiating platform of the CIS may bring risks to all the participants, as it would involve the issues of transfer of national sovereignty, areas for and limits of harmonization, and, most importantly, a balance of interests. Much will depend on the parties’ willingness and the schedule of creating a free trade zone without exemptions and limitations.

It would be more realistic to gradually transfer individual elements of the Single Economic Space to the CIS format for discussion and subsequent adoption, as there emerge economic and political conditions for that. The interests of the further formation of the integration group require that agreements in the Commonwealth not go beyond the boundaries of relevant agreements within the Single Economic Space framework. This will help to gradually create prerequisites for a common economic space and prevent a conflict of interests between the “integration core” (that is, the Customs Union) and the rest of the CIS.

Whereas the normative component will allow creating a system of equal commitments for all the participants within the framework of an integrated economic space, the projects component would fix practical results of the integration process. Both components must be closely interconnected.

The settlement of key issues of labor migration must be a top priority project. It will also require working out a respective legal framework.

It is also advisable to work out concepts and launch a negotiating process on a package of four to five key agreements aimed at streamlining migration processes and enhancing the social protection of migrant workers. Relevant agreements within the framework of the Single Economic Space should be taken as the basis for them.

Some practical tasks can be solved quickly enough in innovation promotion and in the introduction of advanced technologies in the key sectors of the economy. An inter-state target program for innovative cooperation among CIS countries should be approved before 2020. It would create prerequisites for a broader participation of CIS countries in a pan-European scientific and technological space.

It is also necessary to set in motion a joint initiative of the CIS countries on the development of nanotechnologies. This is a cutting-edge area that would lay the foundation for long-term competitiveness of the CIS economies. The establishment of an International Innovation Center for Nanotechnologies in Dubna, a major research center near Moscow, would be one element of the implementation of this initiative.

The signing of an agreement on the establishment of a Council for Cooperation in Fundamental Science would be an important step towards the formation of a common scientific and research space in the CIS. The Council would identify priority areas and forms of interaction between scientists and coordinate the participating countries’ efforts in key areas of fundamental science.

Priority areas should include real measures to increase energy efficiency throughout the post-Soviet space. To this end, it would be expedient to establish an Inter-State Center of the CIS in the Russian Federation for the development of energy-saving technologies. If the CIS countries focus on funding capital-intensive research, this will increase its payoff and will help broaden innovation activities in the region.

The Moscow-based Russian Exhibition Center should become a permanent host to exhibitions of CIS countries, which would be a major factor of developing cooperation in the CIS.

Another project could be aimed at improving the financial and transport infrastructure of cooperation.

It would make sense to:

- work out and approve a concept and an action plan for creating a payment and settlement system based on the national currencies of the CIS countries;

- establish a committee to coordinate the development of transport corridors in the CIS in order to implement a coordinated and integrated strategy for the common transport infrastructure.

It is equally important to create favorable conditions for mutual investments. This is not an easy task, as many interests clash in this field. Yet it is mutual investments that make integration mutually beneficial, efficient and irreversible.

It is also important that the CIS countries draw up an agreement on procedures and mechanisms for resolving investment disputes. The methods and mechanisms for resolving such disputes under existing agreements are not harmonized, they are formulated in very general terms and therefore do not provide stable and predictable guarantees for investors.

One special task is to ensure food security and effective functioning of the agrarian market. In 2010, the CIS countries should:

- finalize the preparation of a Concept for Higher Food Security of the CIS countries;

- implement a project for developing interstate leasing of farm machinery and mechanisms;

- initiate the conclusion of agreements (cooperation programs) on individual segments of the food market. Of most interest is an agreement on the grain market, especially as the Guidelines for the Creation and Operation of the CIS Grain Market for the Period until 2010 will soon expire. At present, the CIS accounts for 12 percent of the world’s wheat production and for almost 30 percent of wheat exports.

Finally, the CIS should back the implementation of projects with efficient development institutions. In particular, they should consider creating a collective mechanism for the implementation of development promotion projects in the CIS – possibly, using resources from the anti-crisis fund. This would also be very important for creating a climate of trust and increasing the responsibility of the more developed countries for the stability and prosperity throughout the Commonwealth.

Both aforementioned aspects of the integration process should be implemented quickly, as proposed in Russia’s initiatives. The more economic benefits the CIS countries will see in integration, the more probable such a scenario will be. The most important thing to do is to ensure a substantial improvement in the business climate in the CIS countries and to create conditions for the emergence of new opportunities for the development of competitive industries and the expansion of markets for their products. At the same time, I would like to point out one factor that may play a very important role in the implementation of integration plans.

MOVING BEYOND THE CIS FRAMEWORKS

Western Europe is now a key market for the Commonwealth of Independent States as a whole, while for many CIS countries it is a market equal or even superior to Russia in importance. It is therefore not surprising that many of Moscow’s partners are already conducting or planning to hold negotiations with EU on free trade. Russia respects their choice. Ukraine started these efforts earlier than Brussels came out with the Eastern Partnership program. Other countries are now considering their opportunities in the context of this EU initiative.

Russia’s accession to the WTO is a key condition for starting negotiations on free trade between Russia and the European Union. It can be assumed that, as economic conditions ripen, all the CIS countries will conduct such negotiations. Naturally, they will have to make very difficult political decisions but, if the economic development of the participating countries is favorable, the dialogue will sooner or later end with the conclusion of agreements.

The content of these agreements is easy to predict. They will provide for free trade in manufactured goods, substantial exemptions for farm produce, and long transitional periods for EU partners. The agreements will also regulate labor migration, including social security issues.

The EU’s free trade agreements with partners from third countries include a normative component, which provides for harmonizing the parties’ legislations in government assistance, intellectual property, government procurement and technical regulation, and a projects component, that is, mechanisms for sectoral cooperation. This structure and content of agreements is easy to combine with the proposed ideology of integration in the CIS. This holds true for the long term as well.

The interests of Russia, the CIS and the EU would benefit from a radical increase of the competitiveness of a large economic space from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Therefore their long-term goal should be to create a common economic space between the CIS and the European Union, with two integration centers – the EU and the Single Economic Space, now comprising three (and later probably more) states.

Curently, the would-be members of the Single Economic Space are working on its legal framework. They take into account the EU legislation: they do not want to create additional barriers, but on the contrary, they want to ensure compatibility with EU laws and regulations when this meets their interests.

Technical regulation is a classic example: Russia is actively using the potential of the European Union’s system of technical regulations (the so-called European Directives). In working on the Treaty on Free Trade in the CIS, we are guided by WTO principles and EU instruments concerning technical regulation or competition policy.

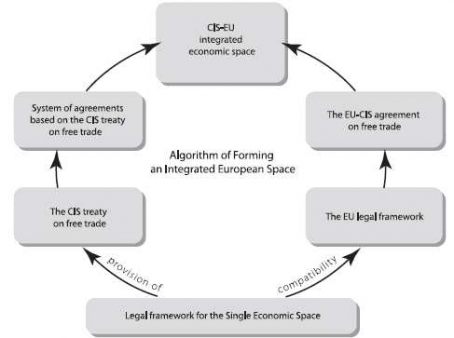

So, at the first stage, it is planned to create a conflict-free common economic environment in the Single Economic Space and further develop it into a system built around the Treaty on a Free Trade Zone of the CIS. This system must be consistent with what has been built in the other part of Europe.

At the second stage, the EU and interested CIS countries will enter into negotiations on free trade, which are expected to take a long time. Simultaneously, the CIS will develop a system of agreements on the basis of the Treaty on a Free Trade Zone. The CIS countries will correlate their integration efforts among themselves and with the European Union. In the long run, this will help create conditions for preparing a general agreement on the principles of free trade in the vast area from the Pacific to the Atlantic. After that, this construct could be proposed to the Asia-Pacific region, where trade policy issues are discussed very actively.

All efforts to remove barriers to trade and investment across Eurasia should complement and reinforce each other. This, perhaps, is the main interest of the business circles and the main incentive for economic growth in the Commonwealth.

The post-Soviet states can take a worthy place in the global economy only if they develop integration processes in the CIS and Eurasia as a whole, if they pool their natural, technological, intellectual and human resources, develop extensive industrial cooperation, jointly use transport communications and, finally, if they integrate their markets. It is only through their mutual integration that they can ensure their rational integration into the world economy, without violating the technological, industrial and institutional structures of their national economies and avoiding the risk of instability.