Introduction: Our World Has Never Been Liberal

A multitude of anti-liberal political forces stormed the Western capitals in 2016. In Austria, Poland, Hungary, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States, those who question the supreme moral authority of liberalism have gained remarkable public support and continue to gain a stronger voice. These sea changes prompted Western observers to sound the alarm that the year 2016 initiated the decline of the liberal international order – reflecting a shared sense of crisis that global liberalism is under siege.[1]

Countering this conventional view, this article argues that the decline of global liberalism is a political myth for one simple reason: Our world has never been liberal. In other words, you cannot lose what you have never had. The standard narrative of a liberal international order implies that the entire world embraced global liberalism after 1991. Our task is, so the story goes, to defend this liberal world from revisionist forces. By and large, this narrative is a fairytale resting on two pillars of illusion: A belief that all Western citizens embraced liberalism as a sole organizing principle of modern political life, and a belief that Russia and other ‘illiberal’ rising powers are aspiring to overthrow the ‘prevailing’ liberal international order. Focusing on political developments in Western societies and the dynamics of Eurasian politics, this article demonstrates that both of these assumptions were unfounded – we have never actually lived in a homogenously liberal world. Hence, the decline of liberalism is not so much about decline; it is simply that liberals are slowly waking up to the fact that our world has not been so liberal in the first place.

Following this short introduction, this article first demonstrates that a plurality of Western citizens have never actively endorsed the rein of global liberalism after the Cold War. Turning to the post-Soviet space, I maintain that the remaking of Eurasia as a new multilateral hub demonstrates that there are indeed alternatives to the liberal way of international life. In conclusion, I argue that peace, stability, and prosperity can be advanced without converting ourselves into believers of global liberalism, but perhaps only through more active collaboration between neighboring countries based on a spirit of mutual respect.

The Undemocratic Expansion of the Liberal International Order

The triumph of Trump has shaken up the American political arena in 2016. Driven by despair, America’s mainstream elites quickly constructed a narrative that Russia meddled in America’s internal affairs, in which Putin’s magic wand (or the ‘disinformation campaign’) turned innocent American citizens into ‘deplorable’ anti-liberals. A fatal fallacy in this argument is the unstated assumption that all Americans had been believers in liberalism prior to the 2016 election. This lacks any factual basis. While America’s liberal elites have aspired to spread ‘American’ liberalism across the world, America itself has never been a homogenously liberal country.

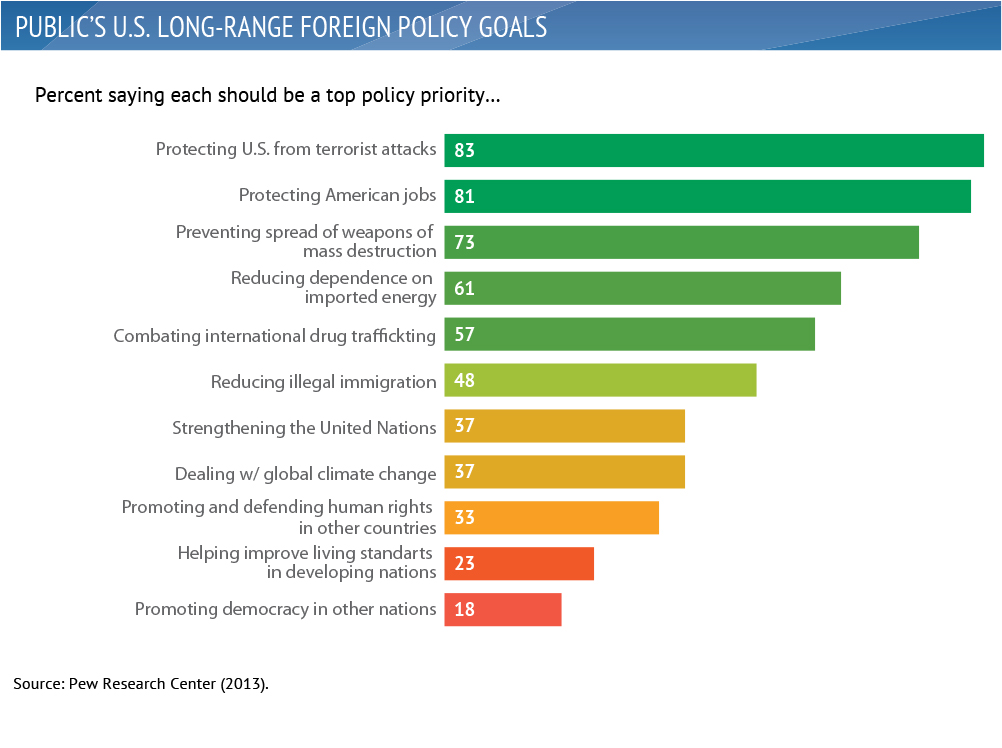

By and large, American promotion of liberal values has been a predominantly elite-driven process with limited public support. Political scientist Ole Holsti already noted in 1992 that there had been a persistent gap between political leaders and ordinary citizens in the United States. The 1990 Chicago Council surveys revealed that almost all American elites (97%) believed that the United States should play a leading role in international affairs, while a great number of ordinary Americans (41%) did not endorse this view.[2] A more drastic picture was revealed by the Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey. When asked what should be the top priority for American foreign policy, less than a third of American citizens (33%) responded that defending human rights abroad should be a top foreign policy priority. The number was even lower (18%) for promoting democracy across the globe. Ironically, America’s democracy promotion has never been ‘democratically’ supported at home.

The picture is not different on the European political arena. For long, Russia has been named a spoiler of European integration. However, the strongest opposition to the NATO/EU expansion was in fact found within the Euro-Atlantic community. A 1997 Pew Research Survey revealed that a great number of American citizens (40%) opposed NATO’s eastward expansion, while only a narrow plurality (45%) supported the expansionist endeavor.[3] In the special 2006 Eurobarometer survey conducted by the European Commission, only a weak majority of respondents (45%) was in favor of EU enlargement while a significant number of EU citizens (42%) opposed the expansion.[4] In fact, the same survey showed that a clear majority in Germany (66%), Luxemburg (65%), France (62%), Austria (61%), and Finland (60%) opposed the EU’s further expansion. Indeed, at the onset of the ‘big bang’ enlargement in 2004, the 2004 Eurobarometer revealed that public support for the expansion was only 42%, while 39% of EU citizens opposed admitting new members.[5] As such, while liberal elites saw the expansionist strategy as a matter of common sense, Western citizens have never consensually endorsed the expansion of the liberal international order.

In a similar vein, foreign policy preferences of liberal elites have never accurately reflected broader public sentiments. In the wake of the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, for instance, an overwhelming majority of Western elites viewed Russia’s Crimea policy as a “revisionist” challenge to the liberal international order. Hence, Barack Obama’s famous exclamation in 2014 that Western liberal democracies ‘unanimously’ decided to impose punitive sanctions against Moscow.[6] Nonetheless, this ‘unanimity’ never went beyond the narrow circle of liberal elites. In March 2014, Der Spiegel conducted surveys asking whether Germany should endorse Russia’s Crimea policy, revealing that a majority of German citizens (54%) supported Russia’s position.[7] Indeed, former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder passionately defended Moscow, criticizing Brussels for having failed to take into account Russia’s legitimate concerns.[8] This kind of discrepancy is observed no less clearly in the realm of civic advocacy. Liberal political theory stipulates that civil society represents concerns of the general public and advances agendas deemed most pressing to ordinary citizens. In the past decades, however, Western civil society has increasingly become a part of what Harvard scholars Kathrine Gehl and Michael Porter call a ‘politico-industry complex’ – a narrow circle of elite networks which represent special, rather than public, interest.[9] As a consequence, there is a growing mismatch in the distribution of opinions between elitist civil society actors and the general Western public. In reality, the promotion of global liberalism is supported by the liberal civil society, which does not represent the whole of Euro-Atlantic citizens. To be clear, my point here is not that Western civic actors should not promote liberalism. These are private organizations and they may promote values they believe in as long as their activities do no harm others. What is problematic here, however, is their tendency to promote these values in the name of the Western citizens, many of whom, as shown above, do not see themselves as promoters of liberalism.

What is more concerning, the expansion of global liberalism appears to have rested on the systematic exclusion, containment, and suppression of non-liberal voices within and beyond the Euro-Atlantic community. At the height of the Cold War, American diplomat Adlai Stevenson remarked at the United Nations that what distinguished Western liberalism from other ideologies was the lack of value imposition. While the ‘monolithic world’ of communism forcefully promoted global conformity to ‘universal’ socialist values, Stevenson proclaimed that the ‘pluralistic’ world of liberalism allowed each citizen to find and defend his or her own values without being pressured to conform to the views of the majority.[10] Since the end of the Cold War, however, Western liberals have attempted to construct a world where no opposition to liberalism is tolerated. A hundred years ago, Soviet revolutionaries exclaimed that there was no alternative to the socialist way of life. In simplest terms, citizens were given only two choices: to be a ‘good’, ‘decent’, ‘progressive’ and ‘responsible’ socialist, or an ‘uneducated’, ‘selfish’, ‘regressive’ and ‘deplorable’ non-socialist. Today, proponents of global liberalism similarly proclaim there is no alternative to the liberal way of life. Citizens in the world are given only two choices: to be a ‘good’, ‘decent’, ‘progressive’ and ‘responsible’ liberal, or an ‘uneducated’, ‘selfish’, ‘regressive’ and ‘deplorable’ non-liberal. As a consequence, the liberal international order has increasingly acquired a totalizing mentality in which the homogenization of political values across the globe is celebrated, rather than viewed with caution.

Considering these trends, the political earthquake of 2016 is not so much about a sudden shift in civic preferences, but rather an exposure of the liberal consensus as illusionary – an unrealistic assumption that the entire world, since 1991, has embraced liberal values. Already in 1994, Mathew Horsman and Andrew Marshall rightly pointed out that ‘values and ideas that the US and its liberal capitalist allies seek to promote simply are not shared by the vast majority of the world’s population.’[11] Simply, a great number of Western citizens have never been liberal, have never actively endorsed the expansion of the liberal international order, and have never considered the promotion of global liberalism as a matter of priority. This non.liberal segment of the population has never been included in political processes, never been given an opportunity to publicize its views, and has never been taken seriously. Of course, these non-liberals always had the right to express their views. But they have been largely denied the right to be heard in a community where expressing non-liberal views has been treated as a sign of moral failing.

In this context, the remarkable growth of anti-liberal political forces in recent years is driven not primarily by the denial of liberal values per se, but rather by the mounting resentments of non-liberals against the ways in which their voices have been continuously demoralized. In other words, the problem is not with liberalism, but with the ways in which they are imposed upon citizens of legitimately heterogeneous political preferences. While Washington and Brussels have been busy promoting ‘Western’ liberalism, they refused to acknowledge that the West itself has never been homogenously liberal. As a consequence, what followed was not the consensual extension of liberal democratic values, but instead the undemocratic expansion of a liberal international order in which many citizens of the world have been denied a right to choose not to be liberal.

In this restrictive political climate, dialogue for value pluralism has been replaced by a monologue of liberal supremacism – one is either an admirable believer in global liberalism, or a deplorable obstacle to human progress. The proponents of the liberal international order once aspired to build a truly inclusive world based on principles of tolerance, compassion, and mutual respect – a world in which every one of us is given a choice as well as a voice. Betraying this promise, the liberal international order has come to represent global governance of the liberal, by the liberal, and for the liberal. While the West’s liberal elites habitually blame Russia for the failure of global liberalism, it has become increasingly clear that, as the prominent American political scientists Jeff Colgan and Robert Keohane argue, this ‘rigged liberal order’ was never sustainable as long as its advancement rested on the exclusion of non-liberal voices.[12] In the end, absolute morality collapses absolutely.

The Eurasian Renaissance: Restoring the Balance of International Orders

The illusion that we have lived in a monolithically liberal world since 1991 is closely linked to the allegation that Russia is attempting to rip apart the liberal international order, especially in the post-Soviet space. But again, here lies the same problem: Neither Russia, nor anyone else, can possibly ‘undermine’ liberalism in post-Soviet Eurasia where it has never taken root in the .rst place. Indeed, liberal ideas have never entered the political mainstream in the region, even among the most globally-minded post-Soviet citizens. In her book ‘Democracy in Central Asia’, University of Kentucky Professor Mariya Omelicheva looked at the kinds of political ideas underlying regional governance in Central Asia.[13] Relying on focus-group discussions, her research looked speci.cally at young political elites who had been selected to study in American universities with funding from the US government, individuals who had been regularly exposed to liberal ideas throughout their study programs. Surprisingly, even among this most globalist segment of post-Soviet citizens, the support for liberal ideas remained very limited. Rather, these American-educated young adults repeatedly expressed deference to the statist model of regional governance advocated by Moscow, defending the principles of state sovereignty, non-interference, and hierarchy.

Indeed, Omelicheva’s findings are consistent with a broader trend in the region. A 2015 Gallup survey revealed that, although the image of Russia had been devastated by the Ukrainian crisis, the support for Russia’s regional leadership remained extremely high among post-Soviet citizens in Tajikistan (93%), Kyrgyzstan (79%), Kazakhstan (72%), Armenia (72%), Uzbekistan (66%), and Belarus (62%).[14] To be sure, the high level of public support does not prove that Russia is a ‘good’ country with ‘correct’ views. Nevertheless, it manifests that the ‘fundamental’ values of liberalism have in fact never been actively endorsed by citizens of the region. Since post-Soviet Eurasia has never been liberal, neither Russia nor anyone else can possibly ‘overthrow’ the liberal international order which has never taken root there in the .rst place. Indeed, this is why Oxford Professor Andrew Hurrell forcefully argued that Russia has been a status-quo power interested in maintaining the statist regional order, which has ruled the region for decades, if not centuries.[15]

While there has existed a tacit agreement that liberalism could not be the guiding principle for Eurasian politics, alternative ideas for organizing post-Soviet international life have not been clearly articulated. In the 1990s, Russian foreign policy remained rather isolationist, and Moscow failed to play a leading role in organizing post-Soviet regional politics. When Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev put forward the idea of creating a Eurasian Union back in 1994, Russian elites did not take the proposal seriously. Since the late 2000s, however, Russia has increasingly committed itself to regional multilateral initiatives. As a result, post-Soviet Eurasia has become increasingly interconnected by a growing number of multilateral institutions, such as the Eurasian Economic Union, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Collective Security Treaty Organization, among others. These new regional initiatives play a pivotal role in the remaking of regional orders, restoring the balance of international ideas, and ultimately contributing to the pluralism of international orders. In short, the rebirth of Eurasia as a rising hub of multilateral cooperation has demonstrated that liberalism is not the sole way of organizing international politics in the post-Cold War world.

Leading this process, the objective of Russian foreign policy should not be opposing the viability of liberal values, but instead preventing the monopolization of political legitimacy by the proponents of global liberalism. For this purpose, Russian leaders should develop a carefully-crafted engagement strategy to link Eurasian regional organizations with potential partners with shared statist values, including countries in the Greater Eurasian region such as South Korea, the Philippines, Japan, Serbia, and Turkey as well as regional organizations from other part of the world such as the Union of South American Nations. Ultimately, the multipolar world is not only about a more even distribution of material capabilities, but also about restoring the moral balance – a balance of order promoting a world in which a lively competition of international ideas, not the conformity to a single ideology, propels human progress.

Conclusion: Russia’s Responsibility to Balance

In the wake of anti-liberal sentiments across the Euro-Atlantic community, it has become rather fashionable to denounce the proponents of global liberalism as arrogant, intolerant, and inflexible imposers of moral dogmatism. To some extent this may be true, but this is not the point. As I have emphasized above, the problem is not with liberalism, but with the highly unusual circumstance it has been placed in since the end of the Cold War. The renowned international lawyer Lassa Oppenheim once remarked that healthy development of international law requires a balance of power.[16] This was because a lack of meaningful opposition would eventually corrupt even the most virtuous world rulers. Liberalism is no exception. The lack of meaningful opposition structurally allured Western liberals to adopt an expansionist foreign policy, prompting them to prioritize the maximization – rather than the optimization – of the liberal international order. The internal revolt we observe today therefore is an inevitable swinging.back of the moral pendulum, in which liberals are painfully discovering that our world has not been so liberal since 1991.

Contrary to the conventional view, however, this article maintains that the rise of opposition to the liberal international order strengthens, rather than weakens, its viability. This is because the emerging balance of international orders – driven by the internal realignment of political forces within the Euro-Atlantic community and the rise of new hubs of multilateral cooperation across the globe – disciplines the proponents of the liberal international order. As the world without opposition is coming to an end, Western liberals now face mounting structural pressure to undertake a careful reconsideration. In this regard, the remaking of Eurasia as a rising hub of multilateral cooperation has demonstrated that peace, stability, and prosperity can be advanced without all becoming believers of global liberalism. The consolidation of the statist international order in Eurasia has broken up the global monopoly on international legitimacy, demonstrating that there are indeed alternatives to the liberal way of international life. In this process, Russia has played, and will continue to play, a pivotal role by providing moral balance, defending the pluralism of international orders and thwarting the concentration of moral authority. In so doing, Russia fulfills the responsibility to counterbalance the world’s ruling ideology. Perhaps for the first time since the end of the Cold War, the liberal international order faces meaningful opposition. And this is a good thing for liberals, who are in dire need of structural restraint and self-reflection.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai International Discussion Club

[1] Kagan, R, 2017, ‘The twilight of the liberal world order’, Brookings Report, 24 January.

[2] Holsti, O, 1992, ‘Public opinion and foreign policy: Challenges to the Almond-Lippmann consensus’, International Studies Quarterly, no. 36(4), p. 439–466.

[3] ‘Public Indifferent about NATO Expansion’, 1997, Pew Research Center, 24 January. Available from: http://www.

people-press.org/1997/01/24/public-indifferent-about-nato-expansion/#support-for-enlargement-general-in.nature

[4] ‘Attitudes towards European Union Enlargement’, 2006, Special Eurobarometer. Available from: http://ec.europa.

eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_255_en.pdf

[5] For the analysis of public support for EU enlargement, see: Timu., N, 2006, ‘The role of public opinion in European Union policy making: The case of European Union enlargement’, Perspectives on European Politics and Society, no. 7(3), p. 336–347.

[6] Palmer, D, 2014, ‘President will sign Russia sanctions bill’, Politico, 15 December. Available from: https://www.politico.com/story/2014/12/senate-russian-sanctions-bill-113552

[7] ‘Using Germany’s Ostpolitik for Crimea crisis’, 2014, Deutsche Welle, 27 March. Available from: http://www.

dw.com/en/using-germanys-ostpolitik-for-crimea-crisis/a-17521658

[8] Paterson, T, 2014, ‘Merkel fury after Gerhard Schroeder backs Putin on Ukraine’, The Telegraph, 14 March. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/ukraine/10697986/Merkel-fury-after-Gerhard.Schroeder-backs-Putin-on-Ukraine.html

[9] Sparshott, J, 2017, ‘Harvard Business School’s Latest Case Study Looks at American Politics and Finds a Rigged System’, Wall Street Journal, 13 September. Available from: https://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2017/09/13/harvard.business-schools-latest-case-study-looks-at-american-politics-and-finds-a-rigged-system/

[10] Quoted in: Weldes, J, 1996, ‘Constructing national interests’, European Journal of International Relations, no.2(3), p. 275–318, 297.

[11] Horsman, M & Marshall, A, 1994, ‘After the nation-state: citizens, tribalism and the new world disorder’, London: HarperCollins, p. 166.

[12] Colgan, JD & Keohane, RO, 2017, ‘The Liberal Order Is Rigged: Fix It Now or Watch It Wither’, Foreign Affairs, no.96(3), p. 36–44.

[13] Omelicheva, MY, 2015, ‘Democracy in Central Asia: competing perspectives and alternative strategies’, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

[14] ‘Rating World Leaders: What People Worldwide Think of the U.S., China, Russia, the EU and Germany’, 2015, Gallup News, 22 April. Available from: http://www.gallup.com/services/182771/rating-world-leaders-report.download.aspx

[15] Hurrell, A, 2006, ‘Hegemony, liberalism and global order: what space for would – be great powers?’, International Affairs, no. 82(1), p. 1–19.

[16] Oppenheim, L, 1905, ‘International Law: A Treatise’, vol. 1, London: Longman, Green & Co.