Abstract

The development of the Russian Far East, which has been declared by President Putin a “national priority for the 21st century” has so far not fully lived up to expectations. The key problem is that numerous tools for an accelerated development of the region are used without a clear idea of what its future should be like and without an analysis of its competitive advantages and factors that restrain economic growth.

This article analyzes these advantages and restraints through the lens of the new international trade theory and new economic geography. The focus is on economies of scale, the use of the advantages of which is a prerequisite for the competitiveness of companies producing manufactured goods. According to these theories, the main obstacles to accelerated growth in the Russian Far East are the insufficient size of the market and the continuous population distribution pattern, a Soviet legacy which makes it impossible to use the benefits of agglomeration.

Given a small population size and large distances, the problem of insufficient market size can only be solved by giving companies access to consumers in other countries, primarily the Asia-Pacific region, liberalizing trade with leading Asian economies, and pursuing a more adequate trade policy to support exports to APR countries. Regional and social policies should be geared towards promoting greater mobility of the population to incentivize people to go to those parts of the region that have the best growth prospects.

Recognizing the importance of scale economy means recognizing the key role of industrial policy which becomes particularly valuable when the market is lacking in size. In the Far East it could be applied to resource-intensive industries focusing on exports to the Asia-Pacific region. As innovation and resource sectors tend to merge worldwide, the Russian Far East should be turned into an area of innovative resource-based economy, thus laying the groundwork for its development strategy in the coming decades.

Keywords: Russian Far East, regional policy, economies of scale, new international trade theory, new economic geography, Asia-Pacific region

In his annual Address to the Federal Assembly in December 2012, President Vladimir Putin stated that “in the 21st century Russia’s development vector goes eastward” (Putin, 2012b). Prior to that, the Ministry for the Development of the Far East had been created, huge amounts of money invested to host an APEC summit in Vladivostok, and Putin had called for catching “the Chinese wind” in the sails of the Russian economy (Putin, 2012a).

This marked the beginning of Russia’s turn to the East, which acquired a new impetus after Russia’s relations with the West had taken a steep downward plunge, entailing sanctions. The main purpose of the turn is to capitalize on the rapid growth of Asian countries, which play an increasingly important role in world politics and the share of which in world GDP keeps rising (Valdai Discussion Club, 2014).

Many countries have been seeking to step up cooperation with Asian economies in the past two decades. What makes Russia’s turn to the East quite distinct is that its external aspect is inseparably linked with the internal aspect, namely, an accelerated development of the country’s Asian part. This relationship can be described by a simple principle: Russia cannot become a full-fledged part of the Asian economy until its Asian part ceases to be the country’s periphery (Valdai Discussion Club, 2014).

The past five years have seen extensive efforts to accelerate the development of the Russian Far East and overcome this peripheral status. In 2012, the Russian government created the Ministry for the Development of the Far East; in 2013, it adopted the Program of Social and Economic Development of the Far East and the Baikal Region (revised in 2014 and 2016); in 2014, the parliament passed a law on Special Advanced Economic Zones and in 2015, a law granting Vladivostok (and subsequently other Pacific ports) the status of the porto franco. According to the ministry, the region has created the most favorable administrative and tax regimes in the Asia-Pacific region and can grow at a rate of 8 percent a year.

Academic literature has lately been paying a lot of attention to Russia’s turn to the East (Kuchins; 2013; Valdai Discussion Club, 2014; Mankoff, 2015; Fortescue, 2016; Korolev, 2016; Vakulchuk, 2017; Makarov, Stepanov and Kashin, 2018). The regional aspect concerning the development of the Far East has also been researched quite thoroughly (Makarov, 2015; Blakkisrud, 2016; Lee and Lukin, 2016).

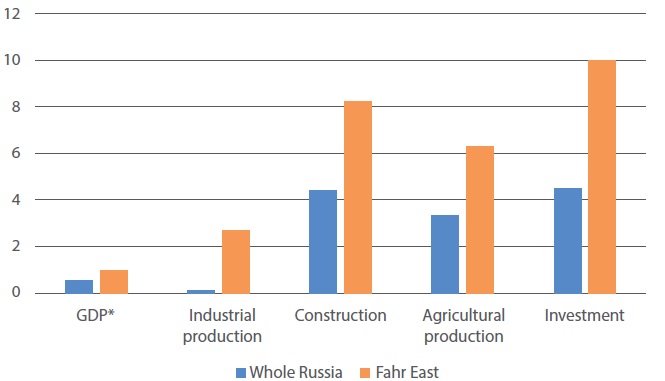

Although little time has passed for assessing comprehensively the results of the policy of accelerated development of the Russian Far East, some of them are already obvious (Valdai Discussion Club, 2016; Ming, Kang, 2016; Avdeev, 2017; Zausaev, Kruchak, and Bezhina, 2017). Over this time eighteen Special Advanced Economic Zones have been created. According to the data provided by Far East Development Corporation, 1,200 companies will become their residents or the residents of the porto franco zone by the end of 2018, including 70 companies with foreign capital. The volume of declared investment is around 2.8 trillion rubles; 102,000 jobs will be created within these projects (Tikhonov, 2018), and 130 new companies are already operating in Special Advanced Economic Zones and in the free port of Vladivostok which have invested 260 billion rubles and created 14,000 jobs (Tikhonov, 2018). As for macroeconomic performance, the Russian Far East has for the last five years been demonstrating an economic growth rate that is higher than the national average. Industrial and agricultural production, construction, and investment—all these indicators of the Far Eastern economy show better dynamics than in other Russian regions (Fig. 1). Yet their growth rates are not high enough and demonstrate a fast recovery from the crisis rather than an accelerated growth. In addition, the production growth has not led to higher living standards, and people keep leaving the region. For instance, according to Rosstat data, net migration outflow from the Russian Far East exceeded 17,000 people in 2017 and is expected to increase in 2018. Taking into account the current economic performance of the region, there is no way to expect a growth rate of 8 percent in the Russian Far East.

Figure 1. Some indicators of economic development of the Far East and Russia in 2014-2017, % of the previous year, average for 2014-2017

Note: Data for GDP – for 2014-2017

Source: Rosstat, Osnovnye rezul’taty…, 2018

The Far Eastern policies implemented over the past years are far from the first attempt of the Russian government to foster economic development of this region. Thornton (2013) and Larin (2013) provide a comprehensive overview of the history of Far Eastern policies; most of the previous attempts to launch sustainable economic growth in the region failed. Despite the fact that new measures aimed at developing the region differ a lot from the previous ones (Valdai Discussion Club, 2014), many experts remain pessimistic about their ability to make the region a driver of the Russian economy (Larin, 2018).

This paper is distinct from other studies in that it analyzes the efforts to develop the Far East from the perspective of the new international trade theory and new economic geography. We believe that these theoretical constructs, which focus on the economic nature of space and market size, can shed light on the factors that impede accelerated economic growth in the region. We suggest that the new policies to develop the Russian Far East can hardly be successful if they do not address the fundamental problems of the regional economy: limited size of the market and even distribution of the population that bar the agglomeration effects. At the same time, the paper shows what efforts are needed for such growth to become possible: they should focus primarily on gaining access to external markets and stimulating population mobility within the region.

Section 2 reviews key points of the new international trade theory and the new economic geography theory which provide the methodological basis for this work. Sections 3 and 4 present the results of the analysis of the Far East’s development on the basis of these theories. Section 5 sums up the main implications of this analysis for various aspects of the government policy to develop the region.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

A transition from stagnation to accelerated development in the economy is often discussed in terms of equilibrium states and compared with a seesaw. In order to shift a seesaw from one equilibrium state (the left end on the ground, and the right one in the air) to another (the right end on the ground, and the left in the air), one only needs to apply some force (Leibenstein (1957) called such force a critical minimum effort), and if this force is sufficient enough, the seesaw will then move from one equilibrium to another by itself, due to gravity (Baldwin, 2016). In the economy, the role of gravity is played by economies of scale. The notion of ‘scale economies’ (increasing returns to scale) dates back to Adam Smith but was brought into the academic mainstream by Spence (1976) and Dixit and Stiglitz (1977). It holds that when a company produces and sells more products, production costs per unit decrease. Initially, the company incurs capital costs whose amount does not depend on whether the company produces one or a million units of a product. As the volume of production increases, the company optimizes its production processes, learning from its own and others’ experience, and introduces innovations. A combination of these factors produces positive feedback: the company increases production, which allows it to reduce unit costs, increase the competitiveness of its products and, therefore, boost production still further.

So, economies of scale are an important driver of economic growth.

Economies of scale occupy a central place in two more theories crucial for the Russian Far East. The first one is generally known under its framework name as the new international trade theory devised by Paul Krugman (1980). He states that market size is critical for industries with increasing returns to scale (that is, most of the processing industries that make differentiated manufactured goods). For a large market within a country, international trade provides a key mechanism for acquiring access to it, that is, for making full use of scale economy.

The second theory, the so-called new economic geography, the main aspects of which were laid out by Krugman (1991), and Fujita, Krugman and Venables (1999), studies dispersion and agglomeration effects stimulating the distribution of economic activity in space and, on the contrary, its concentration in a limited area.

Dispersion effects generally include territorial differences. For example, relatively cheap labor prompts transnational corporations to transfer their productive facilities to developing countries. Agglomeration effects include first and foremost economies of scale. Fujita (1996) describes it as positive feedback: more firms place their productive facilities in a certain territory and make a broader range of goods, which means that people’s real incomes grow even though nominal wages remain unchanged. As a result, consumption grows and so does the number of consumers, thus making the territory more attractive to other manufacturers.

The new international trade theory and the new economic geography are quite valuable for explaining the Russian Far East’s problems, mainly because of its precious spatial factor. The Far Eastern Federal District occupies an area of 6.3 billion square kilometers and is bigger than the whole of Europe less Russia. But this territory is scarcely populated. The accelerated development model for this territory, based on non-resource manufacturing, must provide an insight into how to ensure 1) sufficient size of the market to allow the manufacturers to take advantage of scale economy and thus become competitive; and 2) necessary agglomeration effects in order to secure positive feedback described by Fujita.

Although much attention has been paid to the practical application of the theoretical framework of the new economic geography in Russia (Fujita, Kumo, and Zubarevich, 2005; Zubarevich, 2010; Pilyasov, 2011) and researchers have repeatedly addressed the issue of insufficient market size in the Russian Far East (Melchior, 2015; Han, 2018), only a handful of works have directly linked the new Far East development model introduced recently with scale economy, market size, and agglomeration effects. These issues will be addressed in the following two chapters below.

INSUFFICIENT MARKET SIZE

Going back to the seesaw metaphor, the problem of the new policies to develop Russia’s eastern territories is that of the two necessary elements—an impetus from the state, and forces creating positive feedback—they ensured only the former. The state has built a network of accelerated development institutions in the Russian Far East, which were expected to be a sufficient incentive for domestic and foreign investment. However, such an impetus has been already provided to the region several times (Larin, 2013), but has not brought about a new equilibrium of sustainable economic growth. A better tax and administrative regime is unable to become Leibenstein’s minimum critical effort without gravity force—economies of scale. It has not been achieved as the country does not have a domestic market of sufficient size. This is due to a low population density in the region and the underdeveloped infrastructure required to supply Russian Far Eastern goods to other parts of the country.

The domestic market will not be able to grow substantially in the near future due to the inertia of demographic processes. Therefore, the only way to create a market capacious enough to launch self-increasing growth is to allow Russian companies to get access to consumers in other countries.

This would be a natural way. Back in October 2013, addressing a meeting of the Governmental Commission for the Social and Economic Development of the Russian Far East in Komsomolsk-on-Amur, which formulated a model for the region’s accelerated development, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev actually recognized the impracticability of the idea to orient production in the Russian Far East to the national market or markets of individual Russian regions, and the absence of an alternative to an export-oriented model (Pravitel’stvennaya Komissiya…, 2013). Yet almost no positive changes have taken place in this respect since then.

There are several reasons for that. Firstly, already in 2014, the export-oriented model came into conflict with the import-substitution policy launched in response to Western sanctions. Secondly, entering foreign markets requires, in turn, opening one’s own market to foreigners. This is a very sore issue for Russian businesses and the political elite which traditionally protects domestic producers. Also, there is a conflict of interest in the government structure: the Ministry of Economic Development, responsible for economic growth, traditionally advocates the liberalization of trade, while the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the Ministry of Agriculture oppose it. The Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East has no say in this matter at all. The situation is made even more complicated by Russia’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union: any decision to open the market needs to be coordinated with the EEU partners.

As a result, Russia (as part of the EEU) now participates only in two free trade areas (FTAs), although several more are being negotiated. In the Asia-Pacific region, Russia has an FTA agreement only with Vietnam, which may be followed by agreements with Singapore and India. Meanwhile, other countries in the region are interlinked by a network of trade agreements which actually have turned the region into a full-fledged East Asian FTA. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership is expected to further strengthen integration ties among East Asian countries, while the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which has replaced the Trans-Pacific Partnership and which does not include the United States, will open the region to external players—but not to Russia. Given the existing customs barriers in the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean markets, Russian exporters will be unable to compete there with producers from other countries exempt from such barriers.

Another important limitation imposed on Russia by its isolation from trade liberalization processes in the Asia-Pacific region concerns participation in value chains. These chains have become a key form of international economic interaction since the 1990s, when information technologies made it possible to reduce the cost of coordinating various stages in the production of the same product localized in different countries (Baldwin, 2016). This allowed deepening the international division of labor and maximizing countries’ benefits from their specialization not in goods but in stages of their production where they are the best. This form of production organization implies multiple border crossings by components of a product; therefore, it cannot be realized if there are customs barriers.

It was the possibility of participating in value chains that prompted many developing countries to start liberalizing foreign trade in the 1990s. Until then, the dominant view there was that free trade would perpetuate their raw material orientation and ruin their emerging industries which would be unable to compete in foreign markets. Value chains changed everything: thanks to them, the most successful developing countries not only did not lose their industrial production but also became the world’s factories (Baldwin, 2016) due to a combination of cheap labor and technologies from developed countries. Later, as they adopted these technologies and adapted them to their needs, they created independent high-tech industrial clusters.

Siberia and the Russian Far East are now built into international value chains only as suppliers of raw materials. Unless mutual barriers in trade with Asian countries are eliminated, a different form of participation is hardly possible (Makarov and Sokolova, 2018).

Meanwhile, the liberalization of Russia’s foreign trade still frightens the national elite. The greatest source of fear is possible liberalization of trade with China, although the Chinese market is the most attractive to Russian businesses. As a result, the EEU has signed only a framework agreement with China on trade and economic cooperation, which does not remove mutual barriers in trade.

Opponents of a full-fledged free trade area between Russia and China usually argue that “the Russian market will be flooded with Chinese goods.” But this claim is no longer valid. Firstly, the devaluation of the ruble has sharply strengthened the positions of domestic producers, compared with their Chinese competitors. Secondly, due to the transformation of China’s social and economic model, export promotion has ceased to be a key priority in that country. China is actively relocating its production facilities to other countries, slowing down the demand for imported raw materials and accelerating the demand for final consumer goods. These factors reduce risks associated with the opening by Russia of its markets and increase the attractiveness of a free trade area (Makarov, 2017; Makarov, Stepanov, and Kashin, 2018).

Certainly, individual sectors of the Russian economy may suffer from competition. However, they can be individually protected as any FTA agreement can contain exemptions. But this should only apply to individual sensitive industries. If Russia isolates the entire national economy from abstract competition with Chinese goods, it would deny its exporters the opportunity to become the main engine of the country’s economic growth. First of all, this concerns Russia’s eastern territories. It is important to understand that the main condition for these territories’ full integration into the system of economic ties in the Asia-Pacific region is their openness.

A NEW LOOK AT THE FAR EAST’S SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT

One of the Far East’s peculiarities is that its population distribution pattern is largely an artificial creation. Seventy years of Soviet power, which included forced resettlement of whole peoples, the use of prisoners to make up for the shortage of labor in scarcely populated areas, and considerable efforts to bring volunteer resettlers into Siberia and the Far East created a situation where an abnormally large share of Russia’s population lives on the territories least suitable for that purpose (Markevich and Mikhailova, 2013). At the same time, the Soviet Union’s industrial policy, which prioritized the development of large industrial facilities, led to the emergence of one-industry towns which suffered the most after the collapse of the country. Currently, one in seven residents of Siberia and the Far East lives in these towns. Some estimates suggest that about 35% of people residing on these territories would now be living elsewhere, if it had not been for the Soviet Union’s policy (Markevich and Mikhailova, 2013).

Such population structure is of great (but often ignored) importance for implementing plans to speed up the development of the Far East.

Firstly, relatively even population distribution impedes agglomeration effects that would facilitate economic growth. Huge distances and insufficient infrastructure between relatively large groups of consumers hinder the development of the domestic market and, therefore, competitive manufacturing.

Secondly, any efforts to accelerate economic growth in Siberia and the Far East, especially those to liberalize the economy and open up the region to external partners, will aggravate regional disproportions still further. The greatest benefits from these measures will be enjoyed by the more effective Russian companies and regions that will create clusters of competitive industries. Probably, these will be territories with a special status (Special Advanced Economic Zones or porto franco), rich natural resources (for example, some areas in Yakutia and Chukotka) or an advantageous geographic location (for example, the Primorsky Territory). It is in those areas that new jobs will be created, and the level of real incomes and the quality of life will grow. At the same time, uncompetitive industries may lose, together with cities and regions where they are located. The economic situation in depressed regions will only worsen, increasing risks of social tensions. This, in turn, slows down further economic growth.

There are two possible approaches to this problem. The first one is to provide state support to losing regions, try to keep the local population from moving elsewhere, and maintain economic activity there by means of social transfers and government subsidies. This way is dominant in Russia: huge sums of money are spent to preserve the Soviet-era settlement structure which no longer meets the realities of the market economy.

The other approach is to accept the impossibility of preserving the current settlement system and focus on increasing labor mobility so that workers move to competitive regions, thus accelerating economic growth there. In regions where effective economic activity is impossible, priority should be given not to keeping jobs and the local population from decreasing but to providing decent living standards for those who will remain there. This approach is used in most developed countries with depressed regions affected by negative effects of technological progress or globalization. Suffice it to recall Detroit in the U.S. or coal-mining regions in the UK or Germany, or take a look at the spatial development of Canada, where 70 percent of the population is concentrated on five percent of the territory adjacent to the southern border.

If the East of Russia is intended to be developed on the basis of non-resource industries, then the government will need to concentrate the population in a small number of urban agglomerations, where a combination of industrial production and qualified personnel can help create high-tech clusters. In contrast, the extraction of natural resources in hard-to-reach areas should be done using a flexible rotation system without the need to maintain expensive infrastructure for a resident population.

For the time being, Moscow’s spatial development policy towards the Russian Far East is paradoxical: accelerated development in the region is planned to be achieved on the basis of a limited number of priority territories (with the status of Special Advanced Economic Zones or porto franco), where economic activity is supposed to be concentrated. However, this policy does not provide for any changes in the settlement structure. On the contrary, regional authorities have been offered a system of incentives to conserve the present spatial pattern of the population. For example, the system of evaluating governors’ performance forces them to pay special attention to demographic indicators and make every effort to prevent a population outflow. One natural way to accomplish this task is to restrain inter-regional mobility of the population and keep the ineffective population distribution pattern as it is.

IMPLICATIONS FOR GOVERNMENT POLICY

A development strategy for any region should be based on a clear understanding of its competitive advantages and limits. In the case of the Far East, the former include abundant natural resources, relatively skilled and inexpensive labor (especially after the ruble’s devaluation in 2014), and closeness to Asian countries. These competitive advantages provide a solid basis for developing resource-intensive industries geared towards export to growing Asian economies. The above chapters drew on the logic of the new international trade and new economic geography theories to analyze the factors that prevent the region from tapping its potential to the fullest extent possible. They stem from the impossibility for local companies to use the advantages of scale economy due to 1) insufficient size of the domestic market; 2) inaccessibility of external markets; and 3) population distribution barring agglomeration effect. These restraints need to be clearly understood in order to use other principles for implementing the government policy in various areas. These principles are reviewed in this section.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TRADE POLICY

The insufficient size of the domestic market makes it impossible to develop competitive industries in the Far East if they have no access to foreign markets. As a result, one of the conditions for accelerated development of the Russian Far East would be opening it up to Asian markets, primarily by playing a more active role in the trade liberalization process in the region, including through free trade areas with key trade partners.

It will also be necessary for Russia to significantly intensify its trade with Asian countries. Top-level negotiations and the signing of dozens of memorandums of understanding, of which only a few get translated into real deals (involving predominantly raw materials), no longer can or should be its main instrument. It would be much more important, albeit much less noticeable, to do routine work to support medium- and small-sized exporters; devise export credit and insurance mechanisms; create conditions for Russian manufacturers to enter Chinese marketing channels (including through e-commerce); set up industrial platforms in South and Southeast Asia focusing, among others, on the Chinese market; and create joint industrial parks not only in Russia but also in China.

Positive changes are already visible. The development of non-resource exports is one of the key points in the President’s May 2018 decrees. Specific measures include modernizing the exports support system, reducing administrative procedures in foreign trade, and improving the work of trade missions. The Ministry of Economic Development has announced the completion of the import-substitution program. The attitude towards free trade areas is also gradually changing. Liberalization of trade within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is under consideration. Work is in progress to draft a feasibility study for a trade agreement with China. If these measures are fully implemented, the seesaw of the Russian Far East’s economic development may come into a state of equilibrium needed for self-sustaining spiraling growth.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FOREIGN POLICY IN ASIA

The advantage of Russia’s positions in East Asia is that it has good relations with all the key countries of the region while all these countries have long-term tensions with each other. The only problem in Russia’s bilateral relations with East Asian countries concerns the Kuril Islands territorial dispute with Japan that prevents the signing of a formal post-war peace treaty. However, despite this disagreement the past several years have shown unprecedented warming of Russia-Japanese relations. As a result, Russia’s political influence in East Asia is much higher than its economic presence in the region. Given that sustainable economic growth in the Far East is hardly possible without Russian producers gaining access to Asian markets, the main task for Russian foreign policy is to convert this political influence into deeper economic cooperation.

One example of such conversion could be the development of the Primorye Territory and transformation of its core, the free port of Vladivostok, into a transport hub that would unite three major East Asian economies: China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Each of them is concerned about potential strengthening of the positions of the others in relations with Russia. Geopolitical competition between these countries may become an important driver for investment in the Primorye Territory and its integration in the Asian added-value chains. However, this would be possible only if trade agreements with major Asian countries are signed.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL AND SOCIAL POLICY

The new economic geography theory clearly states that concentration of economic activity within several agglomerations is more effective than even and continuous spread of people. The population distribution pattern created in the Far East in Soviet times cannot be changed quickly, but regional and social policy priorities can be redefined in order facilitate growth as much as possible.

Increasing the mobility of people should be one of such priorities. The social and regional policy should aim not to maintain the size of the population in each region (as is now the case) or attract more people from other parts of the country (the purpose of the Far Eastern Hectare program), but to provide incentives for people to concentrate in priority areas, while maintaining decent living standards for those who remain at home.

The potential for increasing the mobility of people in the Far East is rooted in the development of transport (especially aviation) and social infrastructure, as well as the reduction of administrative costs involved in population relocation (registration, health insurance, the placement of children into school or kindergarten, etc.). Most importantly, the government should take a differentiated approach to the development of territories and recognize the unevenness of their economic potentials. Such recognition, among other things, will allow the more successful regions to better use their capabilities, while less competitive regions will have their risks reduced.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT POLICY

The improvement of transport infrastructure is one of the key priorities in the accelerated development of the Far East. But transport infrastructure is a broad notion covering a wide range of projects which cannot be implemented simultaneously due to a lack of funding. The above analysis sets clear priorities for the development of transport infrastructure. They include increasing the mobility of people and making foreign markets more accessible. The former can be achieved by developing regional and local air services, an area where the Russian Far East falls far behind comparable isolated territories such as the U.S., Canada or Brazil. The latter can be done via transboundary railway service projects such as Primorie-1 or Primorie-2 as well as the Russia-Mongolia-China transport corridor (see Likhacheva, Makarov and Pestich, 2018).

IMPLICATIONS FOR INDUSTRIAL AND INNOVATION POLICY

Recognizing the importance of scale economy for ensuring economic growth means recognizing the importance of industrial policy. In the new trade theory this is one of the main components of the government’s strategic interference: targeted state support makes it possible to develop new industries whose production volumes are not big enough yet to allow them to reap the benefit of scale economy and which will inevitably lose to more mature competitors if they do not get state support (Brander, 1986).

When implementing the government policy, it is necessary to clearly understand where exactly it needs to be applied. Given the insufficient size of the domestic market, the best prospects are enjoyed by those industries that make products which are in great demand in Asian markets and which rely on the Far East’s natural competitive advantages—abundant natural resources and relatively inexpensive and skilled labor.

The Far East development strategy should probably focus on building an area of innovative resource-based economy that would integrate high technologies into the resource sector. Such integration occurs in many industries: digital technologies are transforming the power industry; genetic modification and other biotechnologies have revolutionized agriculture, with automated processes and robots successfully replacing human workers; exact sciences have long made their way into the management of water resources, fisheries and forests; and mining technologies have been raised to a completely new level in the past decade. The production of innovative resource-intensive goods and services with a focus on the growing Asian markets running low on natural resources could be a fairly attractive niche for the Russian Far East to take and succeed in.

References

Avdeev, I. A., 2017. The free port of Vladivostok. Problems of economic transition. Routledge, 59 (10), pp. 707–726. doi: 10.1080/10611991.2017.1416832.

Baldwin, R., 2016. The great convergence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Blakkisrud, H., 2018. An Asian pivot starts at home: the Russian Far East in Russian regional policy ‘Russia’s turn to the East: Domestic policymaking and regional cooperation’. In: Blakkisrud, H. and Wilson Rowe, E., eds. Russia’s turn to the East: domestic policymaking and regional cooperation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 11–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69790-1_2.

Brander, J.A., 1986. Rationales for strategic trade and industrial policy. In:

P. Krugman, ed. Strategic trade policy and the new international economics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Dixit, A. and Stiglitz, J., 1977. Monopolistic competition and optimum product diversity. The American Economic Review, 67(3), pp. 297-308. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1831401> [Accessed 30 August 2018].

Fortescue, S., 2016. Russia’s “turn to the east”: a study in policymaking. Post-Soviet affairs. Routledge, 32(5), pp. 423–454. doi: 10.1080/1060586X.2015.1051750.

Fujita, M., 1996. On the self-organization and evolution of economic geography. Japanese Economic Review, 47(1), pp. 34-61.

Fujita, M., Kumo, K. and Zubarevich, N., 2006. Economic geography and the regions of Russia. In: Tarr, D. and Navaretti, G., eds. Handbook of trade policy and WTO accession for development in Russia and the CIS. The World Bank.

Fujita, M., Krugman, P. and Venables, A., 1999. The spatial economy: cities, regions, and international trade. MIT Press.

Korolev, A., 2016. Russia’s reorientation to Asia: causes and strategic implications. Pacific Affairs, 89(1), pp. 53-73.

Kuchins, A., 2014. Russia and the CIS in 2013: Russia’s pivot to Asia. Asian Survey, 54 (1), pp. 129–137.

Krugman, P., 1980. Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade. The American Economic Review, 70(5), pp. 950–959. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1805774> [Accessed 30 August 2018].

Krugman P., 1991. Increasing returns and economic geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), pp. 483-499.

Larin, V., 2013. External threat as a driving force for exploring and developing the Russian Pacific region. Carnegie Moscow Center. May.

Larin, V., 2018. Novaya geopolitika dlya Vostochno? Evrazii [New geopolitics for Eastern Eurasia]. Rossiya v global’noy politike [Russia in Global Affairs], No. 5.

Lee, R. and Lukin A., 2016. Russia’s Far East: new dynamics in Asia-Pacific and beyond. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Leibenstein, H., 1957. Economic backwardness and economic growth. Wiley: New York.

Likhacheva, A., Makarov, I. and Pestich, A., 2018. Building a common Eurasian infrastructure: agenda for the Eurasian Economic Union. International Organizations Research Journal, 13(3).

Makarov, I. et al., 2015. Povorot na vostok. Razvitie Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka v usloviyakh usileniya aziatskogo vektora vneshney politiki Rossi. [The Turn to the East. The development of the Far East in light of the reinforced Asian vector of Russian foreign policy]. Moskva: Mezhdunarodniye Otnosheniya.

Makarov, I., 2017. Transformation of the economic model in Asia-Pacific region: implications for Russia’s Far East and Siberia. In: Huang, J. and Korolev, A., eds. The political economy of Pacific Russia: regional developments in East Asia. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 76-101.

Makarov, I. and Sokolova A., 2018. Evolyutsiya tsepochek dobavlenno? stoimosti v ATR i vozmozhnosti dlya Rossii [Evolution of added-value chains in the Asia-Pacific region and opportunities for Russia]. Prostranstvennaya Ekonomika, 1, pp. 16–36. doi: 10.14530/se.2018.1.016-036

Makarov, I., Stepanov I. and Kashin, V., 2018. Transformation of China’s development model under Xi Jinping and its implications for Russian exports. Asian Politics and Policy, 10(4).

Mankoff, J., 2015. Russia’s Asia pivot: confrontation or cooperation? Asia Policy, 19, pp. 65–87.

Markevich, A. and Mikhailova, T., 2013. Economic geography of Russia. In: Alekseev, M. and Weber, S., eds. The Oxford handbook of the Russian economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Melchior, A., 2015. Post-Soviet trade, the Russian Far East and the shift to Asia. In: Huang, J. and Korolev, A., eds. International cooperation in the development of Russia’s Far East and Siberia. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 61–96. doi: 10.1057/9781137489593_4.

Min, J. and Kang, B., 2018. Promoting new growth: “advanced special economic zones” in the Russian Far East. In: Blakkisrud, H. and Wilson Rowe, E., eds. Russia’s turn to the East: domestic policymaking and regional cooperation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 51-74. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69790-1_4.

Osnovnye rezul’taty, 2018. Osnovnye rezul’taty raboty Ministerstva Rossi?sko? Federatsii po razvitiyu Dal’nego Vostoka za 2017 god [Basic performance indicators of the Russian Ministry for Developing the Far East in 2017], 12 April. [online]. Available at: <http://government.ru/dep_news/32247/> [Accessed 02 Sept 2018].

Pilyasov, A., 2011. New economic geography: preconditions, ideological basis and applicability of the models. Izvestiia Akademii Nauk, Seriia Geograficheskaia, 4, pp. 7-17.

Pravitel’stvennaia Komissiia, 2013. Pravitel’stvennaia Komissiia po Voprosam Sotsial’no-Ekonomicheskogo Razvitiia Dal’nego Vostoka [State Commission on Socio-Economic Development of the Far East]. Zasedaniie, 24 October. [online]. Komsomol’sk-na-Amure. Available at: <http://government.ru/news/7718/> [Accessed 31 August 2018].

Putin, V., 2012a. Poslanie Prezidenta Federal’nomu Sobraniiu [Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly], 12 December. Available at: <http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/17118> [Accessed 30 August 2018].

Putin, V., 2012b. Rossiia i meniaiustchi?sia mir [Russia and the changing world]. Moskovskie Novosti [Moscow News], 27 February. [online]. Available at: <http://www.mn.ru/politics/78738> [Accessed 30 August 2018].

Spence, M., 1977. Product differentiation and welfare. The American Economic Review, 66(2), pp. 407–414 [online]. Available at: <www.jstor.org/stable/1817254> [Accessed 1 September 2018].

Tikhonov, D., 2018. Dostignutye rezul’taty meniaiut vzglyad na veshchi [The gained results change the worldview]. EastRussia, 31 August. [online]. Available at: https://www.eastrussia.ru/material/gendirektor-ao-krdv-denis-tikhonov-dostignutye-rezultaty-menyayut-vzglyad-na-veshchi/> [Accessed 02 September 2018].

Thornton, J., 2013. Regional challenges: the case of Siberia. In: Alekseev, M. and Weber, S., eds. The Oxford handbook of the Russian economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vakulchuk, R., 2018. Russia’s new Asian tilt: How much does economy matter? In: Blakkisrud, H. and Wilson Rowe, E., eds. Russia’s turn to the East: domestic policymaking and regional cooperation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 139–157. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69790-1_8.

Valdai Discussion Club, 2014. Towards the Great Ocean-2. Russian breakthrough to Asia. [online] Available at: http://vid-1.rian.ru/ig/valdai/Twd_Great_Ocean_2_Eng.pdf> [Accessed 30 August 2018].

Valdai Discussion Club, 2015. Towards the Great Ocean-3. Creating Central Eurasia [online]. Available at: http://valdaiclub.com/files/17658/> [Accessed 30 August 2018].

Zausaev, V.K., Kruchak, N.A. and Bezhina, V.P., 2017. A new model for developing the Russian Far East. Problems of economic transition. Routledge, 59(10), pp. 727-735. doi: 10.1080/10611991.2017.1416833