In May 2015, the leaders of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China adopted a joint statement on the integration of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and the Silk Road Economic Belt initiative. The integration of the two largest Eurasian projects will create new conditions for the social and economic development of all participating countries.

The construction of the Economic Belt is part of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). This is a long-time initiative which is expected to be implemented within 30 years. Several international financial institutions have been established to finance the construction of the pan-Eurasian infrastructure: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank ($100 billion), the BRICS Development Bank ($100 billion), and the Silk Road Fund ($40 billion).

There are also plans to create seven “belts” in the fields of transport, energy, trade, information, technology, agriculture, and tourism. These efforts may result in the emergence of a large free trade zone stretching from the north-western provinces of China, via Central Asia, to Central and Eastern Europe. This foreign-economic project is primarily aimed at solving a range of China’s internal problems. The Silk Road Economic Belt will lay the foundation for an accelerated development of China’s western regions by moving production there from coastal areas and by developing related industries and services (logistics centers, terminals) both in China and Central Asian states.

This national project involves all Chinese provinces in full compliance with the “One Belt, One Road” state strategy, proposed by President Xi Jinping in September 2013. For example, Harbin, the capital of China’s northeast Heilongjiang Province, in early 2015 adopted a plan to build the Heilongjiang Land and Maritime Silk Road Economic Belt. This project has been included in the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor as part of the “One Belt, One Road” initiative. The project pursues the following six key objectives:

- Creating a cross-border railway transport system to link Harbin, Manchuria, Russia, and Europe;

- Accelerating the creation of interconnected infrastructure;

- Expanding logistics services;

- Broadening cooperation to protect energy resources and the environment;

- Building cross-border industrial parks and production chains;

- Broadening cooperation in humanitarian and technological exchanges.

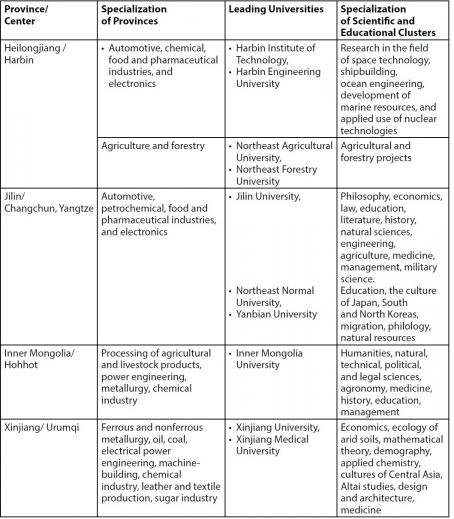

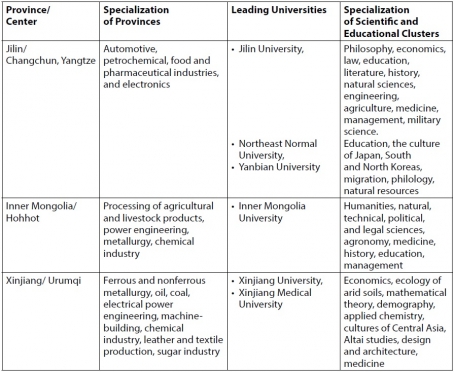

For the purpose of personnel training, the higher education system of China’s north-eastern provinces has been transformed through the creation of scientific and educational clusters. Moreover, a “northern belt of openness” has been created along the borders with Russia and Mongolia within the framework of forming an export model of higher education.

Table 1. Specialization of Scientific and Educational Clusters in Chinese Provinces

Russian sinology

Relevant departments of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and expert networks of its MGIMO University provided the required analytical support for the Russian-Chinese summit. However, the decision to integrate the Eurasian Economic Union and the Silk Road Economic Belt has set fundamentally new economic and technological tasks for sinologists to tackle.

In the Russian Federation, there have long existed several sinological centers (in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Maritime and Trans-Baikal Territories). Until recently, they focused mainly on political and military analysis. Currently, the Russian sinological expert community is small and institutionally fragmented. For example, there are 300 times fewer sinologists in Russia than in the United States and 120 times fewer than in Europe. The fragmentation is due to the existence of three schools of political thought concerning China: these are traditionalists, proponents of international cooperation, and advocates of a multipolar world. In addition to the political differences, Russian sinologists can be divided into three groups in terms of practice and theory: classical sinologists, “new sinologists” and “practical sinologists.”

Table 2. Expert Analysis of Cooperation with China

The development of sinology in each individual country is an important aspect of building a positive image of China. This is why Beijing pays great attention to this issue. According to Chinese scholars, the absence of a clearly formulated program for developing sinology in Russia is a serious obstacle to cooperation between the two countries in this field.

The beginning of cooperation between Russia and China in integrating the Eurasian Economic Union and the Silk Road Economic Belt lays a solid foundation for a long-term strategy for developing sinology in Russia and Central Asia.

New Russian sinology

The integration of the Eurasian Economic Union, where political and institutional leadership belongs to Russia, with the Silk Road Economic Belt, which rests on China’s investment support and technologies, provides a pragmatic context for the development of Russian sinology in the first half of the 21st century. In modern conditions, the main task of the new generation is to ensure cultural and technological exchanges between China and Russia. Its fulfillment requires a more practical approach in sinology and the training of sinologists in the following fields and skills:

- knowledge of the Chinese language (and the two cultures);

- knowledge of system analysis and versatile knowledge about modern China;

- possession of a well-established network of ties and contacts in China;

- technical competence (specialization in a particular natural science or engineering).

The required labor force can be estimated on the basis of technical parameters of the Silk Road Economic Belt, which is 8,400 kilometers long, including 3,400 km in China, 2,800 km in Kazakhstan, and 2,200 km in Russia (the stretch between Moscow and Kazan is 770 km). Labor statistics for similar mega-projects can also give a hint:

- 227,000 people built the Qinghai-Tibet railway (1,950 km), with the high-speed Golmud-Lhasa section;

- the construction of the Baikal-Amur Railway (4,287 km) involved about 440,000 people, and the population of adjacent areas reached two million;

- Russian Railways planned that the construction of a high-speed railway between Moscow and Kazan would create 375,000 new jobs, including 120,000 jobs in areas along the railway. After the railway was to be put into operation, the number of people employed on the railway was to reach 5,600, and the number of new jobs in related industries was estimated at 175,000.

According to expert estimates, it will take 850,000 people (about 200,000 in Russia) to build high-speed sections of the New Silk Road and some 3.5 million people (about 900,000 in Russia) to develop areas along the route. There will be particular demand for such infrastructure jobs as builders, railway men, and power engineering specialists. The development of the “seven belts” will further require specialists in the following areas: information technology, biotechnology, materials science, alternative energy, ecology, agricultural technology, tourism, and medicine.

The construction of one kilometer of a high-speed railway in Europe costs about $50 million. Chinese experts estimate their expenditures at $24-33 million per kilometer, with the bulk of the investments to come from China. So the main benefit of the new Silk Road for China will be in technological, infrastructural and financial dependence of the Eurasian Economic Union countries. A new generation of technical experts who will represent Russia’s interests in Eurasian infrastructure projects should ensure the transfer of technologies and competencies.

One must remember though that the development of the largest high-speed rail network even within one national jurisdiction led to a major train accident on China’s Ningbo–Taizhou–Wenzhou Railway on July 23, 2011. Harmonizing technical specifications and rules during the construction of transport routes and industrial facilities in different countries will guarantee efficient and safe operation of pan-Eurasian infrastructure.

Regional initiative

Specialists equally proficient both in engineering and the Chinese language can hardly be trained at sinological centers in Moscow and St. Petersburg as they focus mainly on political, diplomatic and military analysis. Therefore, Russia’s border regions, primarily those that have the closest ties with China – the Maritime and Transbaikal Territories, should lead the way in developing new applied sinology.

The Transbaikal Territory shares the longest border with China and has well-established ties with all of its northern provinces. Sinologists have been trained in the region since 1960, and now it has its own regional school of sinology. Transbaikal State University has stable and dynamically developing contacts with more than 30 Chinese universities. Students are trained in five areas. In 2011-2015, more than 400 graduates have received qualifications which involve the use of the Chinese language.

In view of the need to train sinologists for Russian-Chinese industrial and raw materials projects, the Transbaikal Territory has proposed setting up a center at its largest university to train Russian-Chinese translators specializing in technical fields. This initiative has been fully supported by the Ministry of Education.

This will be a pilot project aimed at creating a new type of Russian sinology in the Russian Far East and Siberia. In the future, Russian regions participating in the New Silk Road project should create a network of educational clusters, including schools, colleges and universities, as well as small innovative companies, technological and agro parks. Effective development of new applied sinology centers will ensure the successful integration of the Eurasian Economic Union and the Silk Road Economic Belt, and the construction of pan-Eurasian infrastructure for the benefit of all countries of the continent.