The article is part of the project “The Asian Vector in the Russian Economy’s Development” done at the Department of World Economy and World Politics. The authors express sincere thanks to Sergei Karaganov and Timofei Bordachev for scientific supervision of their work.

The booming growth of Asia’s largest economies – China, India, and the ASEAN member-states – is a major factor that has set the tune to the development of the world economy and politics in recent years, all the more so that this growth is taking place against a profound change in global economic processes. The changes were caused by the advent of new structural factors of the economy: climate change, the growing shortage of water, and the increasingly apparent shortage of foodstuffs. Remarkably, whereas for the majority of countries these factors set challenges and restrictions, for Russia, which is located at the foothill of the Asian “volcano,” their combination opens up hitherto unseen opportunities.

THE ASIAN VOLCANO

The global crisis has put a brake on the West’s growth but Asia has sustained dynamic development and, in fact, has become a locomotive of the world economy.

The Asian volcano has woken up to active life and there are no signs to suggest that it may resign to dormancy any time soon. Three Asian nations – China, Japan and India – are among the top five economies in terms of GDP, and the region is likely to consolidate these positions in the future, too. Averaged assessments say China will become the world’s biggest economy in twenty years’ time by outstripping both the EU and the U.S.

China, India and the ASEAN countries account for over 50 percent of the Earth’s population and this means they possess a huge resource of inexpensive workforce that acquires more and more qualification with every passing year. The demographic growth, which is traditional for Asia, has been accompanied by urbanization and a sizable increase of the standard of well-being in recent years. Together, these factors have brought about an explosion-like increase of the demand for many types of products and have turned Asia from a global “assembly shop” into the fastest growing and most promising market.

The Asian growth has both quantitative and qualitative aspects. Asia’s leading countries are visibly diversifying their economies and laying foundations for a more stable and more qualitative economic development. Their internal markets are expanding rapidly, which reduces these countries’ dependence on the global market situation, above all on the economic ups and downs in the developed countries. Asian producer nations have long regarded this dependence as the biggest threat to their stability, and the global crisis has made it evident.

As a result, the Asian states have reserved the segment of “primitive” production of mass consumption goods and have simultaneously begun building up their share on the markets of high-tech and highly processed commodities.

According to the World Bank’s assessments, 21 percent of high-tech exports fall on China (compare this to America’s 13 percent). Singapore is leading in terms of high-tech exports per capita and India is ahead of the rest of the world in terms of computer software manufacturing.

It is not surprising therefore that a large-scale geo-economic struggle for Asia has unfolded in the world in the past few years. The region is becoming the biggest economic and foreign policy priority for other leading centers of power. The largest countries, including the U.S., are seeking to make the Asian growth a factor of and a stimulus for their own economic development, and to fasten themselves to the Asian development locomotive as they consolidate trade and economic relations with Asia and get involved in regional integration processes.

Russia is located in the immediate vicinity of the new gravity center but it uses practically none of the potential generated by it. The scope of foreign economic relations with Asian countries is so insignificant that it does not stimulate the development or modernization of the Russian economy in any way. The Russian government that maintains a conservative, largely Eurocentric policy stemming from the Russians’ traditional admiration of Europe, practically closes its eyes on the growing Asia.

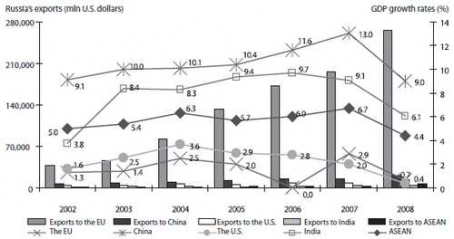

In the meantime, the EU’s averaged annual GDP growth stood at a mere 2.2 percent in the 2000s against the 10 percent posted by China, 7.1 percent by India, and 5.4 percent by ASEAN countries. In spite of this, the EU’s share totals 50.3 percent in Russia’s foreign trade while all the above-said Asian countries account for only 11.6 percent. This “distribution of forces” is illustrated by Graph 1.

Russia’s Exports to the EU, the U.S., China, India and ASEAN

and GDP Growth Rates in Those Countries (per yr btw 2002 and 2008)

Source: Based on the data from the World Bank, the Russian Federal Statistics Service, Eurostat, the ASEAN Secretariat

The dynamics and contents of the existing Russian-ASEAN trade also give grounds for serious concern. For instance, the commodity composition of this trade resembles increasingly that of Russia’s trade with the developed countries of Europe and North America, as mineral resources, crude oil and metals have dominant positions in the Russian exports there, while imports are dominated by industrial products and highly processed commodities. This means that the current state of Russia’s trade with Asian countries reaffirms its specialization as a crude mineral supplier. This country runs the risk of becoming a resource appendage of developed and developing nations likewise in the immediate future unless it diversifies its exports; trade with Asian partners is most likely to remain a torpedoing factor and not at all a stimulus to progress.

Cooperation between Moscow and Asian countries in the field of investment is disappointing, too. The volume of mutual investment is dismal and a greater part of Asian investments in Russia falls on the industries with low degree of product processing, while Russia’s investment in China, India and the ASEAN nations does not exceed 0.5 percent of the total.

The passive attitude of the Russian business and government agencies towards Asian nations continues posing a tangible problem, which arises from the wrong understanding of the processes unfolding in Asia. They are misunderstood by the political and economic elite and public at large. Many Russians still associate China with economic backwardness, dirt-cheap low-quality consumer goods, and the “Made in China” labels a priori make them feel skeptical.

As a consequence, these outlooks produce a lack of an efficient state strategy for interaction with the fast growing Asian markets. Currently, it is the companies from the Russian Far East – sometimes feeble and controlled by criminals – that mostly explore the Asian economies.

Russia is involved in the dynamically developing integration and cooperative processes in Asia in a very inactive manner. Even the future summit of APEC in Vladivostok is still viewed as a big construction project, not as an opportunity for streamlining economic cooperation, one that could provide a powerful stimulus for modernizing the Russian Federation.

AN EQUATION WITH THREE UNKNOWNS

Despite the impressive dimensions, economic growth in Asia bumps into several fundamental restrictions related to the exhaustion of resources. The dragged-out extensive and even predatory exploitation of natural resources has driven the world to a point where it has to solve an equation with three new variables – climate change, shortage of freshwater and deficit of foodstuffs. Given the global nature of the current challenges, the solution of this equation will determine the long-term development of each country in particular and the world at large. Asia, as a center of the world economic growth, will get the biggest blow.

Experts from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change say the air temperature has risen 0.76 °C to date since the middle of the 19th century, and the climatic changes do not confine to global warming only. They also embrace ancillary processes like the change of hydrological regime; the melting of glaciers; the rise of the world ocean level; a growing number of weather calamities, above all hurricanes, droughts and extreme rains; and the change of agro-climatic conditions.

The bitter irony is that both the industrialized countries of the West and Russia, which bear the brunt of responsibility for the ongoing climatic changes, will most likely suffer the least. The developing world will get the heaviest blow. The deplorable impact of climatic change will nail down Africa’s backwardness and provincial position of most countries of this continent; this will bring forth the need for additional international financial aid. As for Asia, it may catalyze entirely new processes there, ranging from changes in the geography of industries and farming to the region’s transition to a new model of economic development based on green technologies. China is moving fast to the world’s top position in terms of the use of such technologies, while South Korea, Singapore and India are elbowing their way into the group of leaders.

The latter has double significance for Russia. On the one hand, the restrictions imposed by climate change and the resultant degradation of the environment force China to suspend the development of some branches of industry and agriculture that can now be accommodated in Russia. On the other hand, an additional stimulus to China’s economic growth based on green technologies furnishes Russia with a new opportunity to use it as a tool for its own economic development.

For Russia itself, the consequences of the global climatic change look controversial. On the one hand, they mean a sizable economy on heating, an opportunity to use the Northern Sea Route, a less expensive development of mineral resources in the northern areas, and a certain improvement of the agro-climatic conditions. On the other hand, it may suffer bad impacts, like the increasing number of natural calamities and aridization (a decrease of humidity that causes a reduction in biological productivity of ecosystems – Ed.) in some southern and western regions, and the threat of destruction of installations located in areas of thawing permafrost.

The problem of freshwater deficit is acquiring more acuteness. Freshwater stress has already affected 1.9 billion people worldwide, and the UN forecasts say that two-thirds of the Earth’s population will be experiencing it by 2050. Water resources are insufficient not only for the growing population but also for agriculture, industrial production and the energy sector. Add to this the growing demand for water by industries producing foodstuffs and commodities in the fast developing countries – a fact that further aggravates the situation. One more factor is the general reduction of atmospheric precipitations in the developing countries.

In the past few decades, the developing countries located in the regions with a shortage of water resources have been demonstrating a stable and continuous demand for freshwater. Their list includes some of Russia’s immediate neighbors: Central Asian states, China and Mongolia. In China alone, a total of 560 rivers are drying out; the Yellow River failed to reach its mouth in 1997. Central Asia is growing more and more arid, especially in the wake of the ecological disaster that has befallen the Aral Sea. Many experts believe the growing anthropogenic burden and the continuous aridization may push the region into wars over access to water resources in not so distant future.

Russia might offer its own water resources to these countries, but trading in water along the same patterns that are used in trading in crude oil is technically complicated and economically inefficient. Yet Russia may take on the leading role on the market of what is known as virtual water, i.e. water contained in products. These are, above all, agricultural products and other water-retaining products. The market of virtual water offers some of the biggest promises worldwide today, as more and more countries prefer to buy water-intensive products abroad where water has a much smaller prime cost rather than manufacture them at home in the conditions of water deficit. An opportunity to become a major international supplier of water opens up before Russia and we must use it.

The foodstuffs problem is discussed less intensely and remains underestimated. In Russia, it is mainly associated with the famine-ridden countries of Africa, while its impact on the countries with relatively higher levels of development is often ignored. More than that, in a situation where everyone is preoccupied with the tertiary sector of the economy, the development of the primary sector, which agriculture belongs to, is looked upon as an atavism unworthy of developed nations, and that is why the farming sector is often “entrusted” to the developing nations.

In the meantime, a country’s ability to procure foodstuffs for its own population and to have a surplus for exports is turning into a serious competitive advantage. It strengthens the country’s international positions and offers a lever for influencing the global economic and political situation.

This factor is largely aggravated by the tangible growth of food prices that are pushed up by the increase of the global population, the growth of energy prices, increase in people’s revenues in developing countries (especially in Asia), the degradation of soil, and a big number of other factors.

Many researchers predict a further rise of foodstuff prices, linking it to the hikes of demand for biological fuel. Struggle with climate change has compelled the governments of many countries to declare a shift towards the use of green energy a priority task. Bioethanol derived from sugar cane, corn and wheat is rising to the top position in terms of demand. As a consequence, production of biofuel takes away the land, water and labor resources from crop farming, and this in turn makes foodstuffs more expensive. Obviously enough, more expensive foods will bring benefits to the countries supplying their own farm produce to the international market.

Add to this that a number of resources essential for agriculture have fallen into the category of short supply items. First, these are arable lands. Only 9 percent of the entire land surface of the Earth can be used as arable land, and the tilling of other lands for crop husbandry seems highly improbable. The world’s total area of arable land per capita has shrunk by 50 percent since the mid-1990s.

Availability of sufficient quantities of freshwater is no less significant for profitable agricultural production but the shortage of freshwater becomes increasingly noticeable across the planet.

In this situation, Russia has undeniable advantages, as it has an abundance of land and water resources. Its reserves of farming-worthy lands are really impressive, since it accounts for 3.3 percent of the world’s total farming lands and 9 percent of total plow lands. The problem is that more than 30 million hectares of the land worthy for agriculture is misused at the moment. Besides, Russia has more than 20 percent of global resources of fresh water.

Climate change is also contributing to the strengthening of Russian agriculture’s competitive advantages – it will help enlarge the areas for growing basic crops, introduce new types of plants, grow warmer-weather and more fertile crops. This will increase the gross yield of crops (although the impact on the productivity of the currently functional lands is difficult to foretell). At the same time, natural conditions for production of foods are deteriorating in the main producer countries – the U.S., Canada Australia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Western and Central Europe, and China – due to climatic change and degradation of soil; and this weakens their positions on the international market.

To sum it up, the unique combination of these advantages brings us to a conclusion that Russia has the world’s highest potential for agricultural development.

The brisk economic activity that has shot up around the world in the wake of the growing role of new structural factors has left Russia aside so far. Not only does this country stay away from the global tendency to develop green technologies, it is not introducing any measures towards adjusting the key economic sectors, including agriculture, the construction industry and energy resource production to the changing climatic conditions. Meanwhile, prudent use of the advantages emerging from the impact of new structural factors may furnish Russia with an opportunity to move to a higher level in the global economic and political hierarchy.

TAMING THE VOLCANO

The rapid economic development in Asia – and especially in China – provides Russia with new opportunities for using its own competitive advantages arising from the new structural factors of global economy. Accent should be made on brisk stepping up of state policies for support of the economic sectors producing commodities that will enjoy the biggest demand in the coming decades, especially among Asian countries. Agriculture will have the leading role here.

Wheat is traditionally at the top in the list of most widely demanded commodities. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) forecasts suggest that wheat prices will be 15 to 40 percent higher in the next decade than in the period of 1997 through 2006. The global foodstuff crisis that broke out in the first years of the 21st century compelled the world community to reconsider its capability to procure food for itself in the short term. The global reserves of wheat fell to a record low point and there is no way to replenish them rapidly to a level that would help cushion the shocks of agricultural shortfalls.

This situation offers Russia unique opportunities for increasing agricultural production. It has huge resources for expanding the cultivable lands (by no less than 10 million hectares) and for a simultaneous increase of the productivity of the grain crop sector (the yield of grain crops can be increased by no less than 2.5). No other country in the world has a comparable potential.

If Russia attains growth in the production of grain, China may become its main purchaser over time as its own production of wheat has fallen in the past few years. This fall was caused by the excessive load on agricultural lands and inexpert use of farmlands; their overall deficit (only 9 percent of the country’s territory is used for agricultural purposes); and the exhaustion of subsoil waters and erosion of soils across the country. All these trends are unfolding against the backdrop of the growing demand for grain.

Production of meat holds an even greater promise as a sector where Russia can succeed. People in China, Japan, South Korea and some other Asian countries have cut down the consumption of traditional foodstuffs like rice or noodles in recent years and have increasingly used foods rich in protein. Meat and meat products have turned into the most dynamic commodity on the world food market. FAO experts predict that the demand for protein foodstuffs will continue growing at a fast pace by the middle of this century as the planet’s population continues increasing along with per capita incomes and urbanization.

From 1990 through to 2007, the per capita consumption of meat in East Asian countries grew 2.5 times. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) forecasts an almost doubling of meat consumption by 2050. India also gives grounds to suggest that the typical food ration will change there soon. A number of researchers claim the vegetarian character of the Indian civilization hinges on poverty (which it has started overcoming of late) rather than on religious rules.

Production of meat requires huge quantities of water, which Asian countries do not possess. Even China that accounts for 30 percent of the global turnout of meat products has to build up imports of meat by dozens of percent annually, since domestic production, huge as it is, fails to match the growing demand. Nor should one forget that China traditionally relies on crop cultivation while animal husbandry has always been regarded as secondary, and its development has been left without due attention.

In Russia’s case, the absence of sufficient demand has until most recently been regarded as the main barrier to livestock breeding. Now this demand is rising and Russia should and must aspire to meeting at least a part of it. The general situation on the world markets of foodstuffs will likely be favorable for this. FAO forecasts say the prices for pork and beef may go up 30 percent by 2018 and the prices for poultry may increase more than 30 percent.

Thus, a market niche of unprecedented size that has emerged in Asia opens up really tantalizing prospects for the Russian producers of meat and meat products.

Together with the hiking demand for the main categories of food, there has been a visible growth of consumption of some other groups of foodstuffs, especially alcoholic beverages. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the Chinese have increased the consumption of alcohol (measured in liters per capita) by a factor of three, and the purchases of beer by a factor of 5.5. The demand for imported alcohol beverages is rising; for instance, the imports of beer have gone up 150 percent since 1990. The general deficit of foodstuffs, the heavy contamination of water and the shrinking farmlands means that Beijing’s dependence on foreign suppliers will continue swelling.

Foreign brewers’ operation on the Chinese market is hampered by the specificity of the local consumer tastes. Several Russian brewing companies have already made attempts to supply their products but were unsuccessful. To occupy this niche on the Chinese market, Russian companies should precisely target at the Chinese customers’ tastes and increase the quality of their products. There are no any other obstacles to Russian producers on the Chinese market.

Furthermore, the developed nations that grow the bulk of brewing barley today have practically run out of reserves for expanding the cultivation areas. Russia, in contrast, has huge reserves for expanding the cultivation of brewing barley and hop plant. Also, it boasts huge resources of low contaminated water, which creates bright prerequisites for beer production, above all, for the potently growing Asian market.

However, Russia’s highly potent development of agriculture is thwarted by a deficit of relatively low qualified workforce needed for this sector, especially in the wake of the small density of population in a number of Eastern regions. Invitation of labor migrants from Central Asia, India or China might offer a solution in this case. The historical agricultural traditions in these countries, the moderate demands for wages, the geographic closeness to Russia and the willingness to work in this country make labor migration from those regions especially lucrative. Importantly, accent should be made on seasonal migration and work in shifts. As of today, however, this pattern of attracting foreign workers runs into a range of institutional limitations arising from legislative imperfections. These obstacles can nonetheless be cleared away if the Russian authorities summon political will.

Russia’s pulp and paper industry also stands to get an extra stimulus from the East Asian markets. In spite of the general tendency towards replacing paper data carriers by the electronic ones, the Asian countries show a stable high demand for paper. In addition, the growing concerns over environmental problems lead to increased use of paper as a package material. A broad promotion effort is being made to replace cellophane by paper in packing.

On this background, the production of paper in the East Asian countries bumps into a range of resource limitations linked first of all to the shortage of water, which the pulp and paper industry requires in huge quantities. Already now China is importing more than 20 percent of the paper it consumes and this percentage will continue growing. The Chinese government recognized the insufficiency of own resources for meeting the demand and lifted customs duties on most types of imported paper in 2005. It also signed a number of agreements on paper supplies with Indonesian, Japanese and Finnish companies. Somewhat earlier, the import duties were lifted by Taiwan and South Korea.

As is well known, the Finnish pulp and paper industry uses mostly the Russian raw material, which means that China is already importing Russian processed timber but is doing so in bypass of Russia. In the meantime, this country would benefit from getting to the Chinese market on its own with an end product. But for this purpose Russian paper should gain competitiveness; today its quality does not stand a comparison with the world leaders of the industry – the U.S., Sweden, Germany and Canada.

Currently, Russia exports 45 percent of products of the pulp and paper industry but the bulk of these exports is made by low quality newsprint. Russian factories simply do not manufacture some types of high quality paper. In the meantime, the riches of Russian forests enable our producers to raise substantially the output of paper provided they modernize their production facilities. The export of paper (mostly of high quality) should replace the export of timber, which is inefficacious from both the economic and ecological points of view. China should remain a major target market for Russia.

Considering the fact that a country wishing to specialize in the exports of commodities should rely on the resources it has in abundance (this stipulation received the name of the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem in economics), Russia should naturally specialize in the economic sectors that require big quantities of land and water. And if the production in these sectors is propped up by a dynamically growing global demand, they have every right to claim the priority status in the national strategy of economic development.

Agriculture and the pulp and paper industry exactly fall into this category. These are but the most obvious examples, the list of priority industries can be continued. Most importantly, Russia’s strategy of foreign trade and economic policy should rest on a clear understanding of today’s global economic realities and their unending change.