The odd situation with Ukraine’s choice of an economic integration vector makes one ponder about an optimal combination of political and economic factors in regional integration. What makes the situation odd is that the course towards European integration, which Kiev is being pressed to take, is economically flawed. An analysis by leading Ukrainian and Russian economic experts shows that an EU-Ukrainian free trade zone will inevitably make it hard for Ukraine to develop or even sustain economic ties with the Customs Union in all major areas. This will result, above all, in curtailment of joint R&D in aircraft making, power machine-building, aerospace equipment production, nuclear power industry, power engineering, and shipbuilding. An EU-Ukrainian free trade zone deal, which will naturally force the Common Economic Space member countries to take measures to protect its market, will also impact other vulnerable sectors of Ukraine’s economy, such as food production, transport vehicle and equipment manufacturing, and agriculture. Ukraine’s share in Russian imports of foodstuffs is expected to plunge by one-third. An increase in the balance of trade deficit, along with the fading opportunity to borrow from foreign states, threatens Ukraine with default, and jeopardizes the EU’s political pledges of supporting its new associated member.

The simple question “Why make a political decision that would spell an economic disaster for a major East European country?” has as simple an answer, formulated by lobbyists for Ukraine’s integration with Europe: to prevent Ukraine’s integration with Russia in the Common Economic Space of the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC). As Ukrainian opposition member Yuri Lutsenko said, “Ukraine’s Association Agreement with the European Union is an emergency brake to stop its progress towards integration with Russia.”

HOLLOW PROMISES

To calm down the Ukrainian public, European political emissaries resort to barefaced lies. European Commissioner for Enlargement and Neighborhood Policy Stefan Fule is spinning tales that an EU-Ukrainian free trade zone will secure a six-percent annual GDP growth for Ukraine (the statement was made at a round table discussion in the Ukrainian parliament on October 11, 2013). However, all estimates, including those made by European analysts, point to an inevitable slump in the production of Ukrainian goods in the first few years after the signing of the Association Agreement, as they are bound to lose competition to European goods. Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt’s statement (made at the 10th Yalta Forum “Changing Ukraine in a Changing World: Factors of Success” on September 20, 2013) is even more reckless. He claimed that Ukraine’s membership in the Customs Union would cause its GDP to plunge by 40 percent, and promised a 12-percent growth of GDP if Ukraine signed the Association Agreement. Meanwhile, all estimates suggest a 6 to 15 percent growth of Ukraine’s GDP by 2030 within the Custom Union.

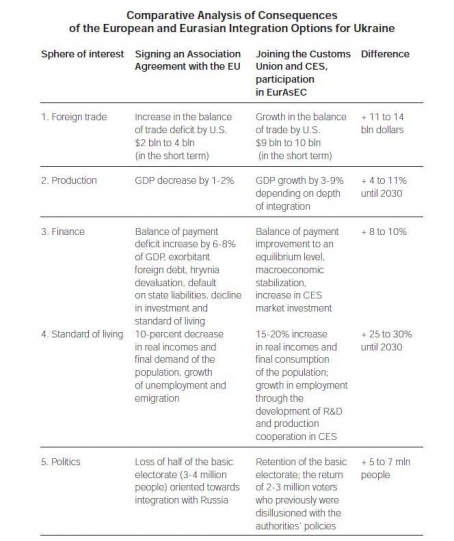

A comparative analysis of Ukraine’s two economic integration options seems to leave no room for doubt: participation in the Eurasian integration project would increase Ukraine’s GDP by 7.5 percent by 2030, compared to a GDP level that an association with the EU would bring (see Table 1). Whereas the Eurasian integration promises an immediate major improvement of Ukraine’s balance of trade and stability of its balance of payment, the EU Association option will entail a worsening of trade conditions and direct economic losses for Ukraine. The first option will ensure the necessary conditions for sustainable development of the Ukrainian economy and will improve its structure; the second one will bring about its degradation and bankruptcy. Nevertheless, Ukrainian opposition leaders and integration adepts ardently call for association with the EU.

Moldova is another country facing the same challenge. Moreover, its association with the EU would not only hit the economy, already in a pitiful state, but would also aggravate its conflict with the breakaway Dniester Republic.

Until quite recently, Armenia, too, was pressed to make a similar political choice. Its association with the EU would not only entail economic losses, but weaken Armenia’s positions in the international arena.

An unbiased analysis reveals purely political motives behind the EU’s Eastern Partnership policy, aimed at blocking opportunities for former Soviet republics to participate in Eurasian economic integration with Russia. The anti-Russian essence of this policy is clearly seen in consistent efforts by politicians and secret services of NATO member-states to interfere in the internal affairs of the newly independent states, ferment anti-Russian propaganda and foster anti-Russian political forces. All “color” revolutions inspired by the West in the post-Soviet space were rooted in frenzied Russophobia and aimed at preventing integration with Russia. The economic losses and social calamities resulting from such policies in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine and Moldova would not matter.

The isolation of former Soviet republics from Russia inevitably worsens their economic situation due to the severance of cooperation ties and loss of established sales markets. To force these economically wicked decisions, the Eastern Partnership policy seeks to strip the Eastern partners of their sovereignty in foreign trade issues. Draft agreements on association with the EU spell out a commitment to unquestionably comply with EU directives on trade policy, technical and customs regulation, sanitary, veterinary and phytosanitary control, subsidies and government procurements. The countries associated with the EU do not have any right to participate in drawing or adopting these regulations; they must obey them unconditionally. They also pledge to take part in settling regional conflicts under EU guidance.

In other words, former Soviet republics that sign Association Agreements are assigned the role of colonies which must comply with EU jurisdiction in trade and economic regulation.

For example, throughout all its sections, the draft Association Agreement makes Ukraine undertake a wealth of commitments. The key thesis is formulated in Article 124 of the Agreement: “Ukraine shall ensure that its existing laws and future legislation will be gradually made compatible with the EU acquis.” To dispel any doubts as to the integration vector, Article 56 clearly states that “Ukraine shall refrain from amending its horizontal and sectoral legislation listed in Annex III to this Agreement, except in order to align such legislation progressively with the corresponding EU acquis, and to maintain such alignment.”

This means Ukraine will be unable to use the instruments envisioned by the Customs Union agreement for eliminating technical barriers to trade with CIS countries that are not members of the Union. Also, the memorandum of cooperation in the sphere of technical regulation signed by the Ukrainian government and the Eurasian Economic Commission last year appears meaningless.

A special supra-national body – an Association Council – will monitor an associated member’s commitments. Its decisions are binding on the parties.

Economic expediency is not considered in discussing this political decision. The EU has ignored the Ukrainian Cabinet’s timid attempts to broach the question of investments to modernize the Ukrainian industry in order to have it adapted to the European technical regulation norms and ecological requirements. According to calculations by Ukrainian experts from the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences, Ukraine needs at least 130 billion euros for the purpose, which the crisis-hit EU clearly cannot provide.DEPLORABLE RESULTS

The political decisions by former socialist republics of Eastern Europe and the Baltic States to join the European Union have proven to be economically flawed. After gaining EU membership, these states have lost about half of their industrial production and a considerable portion of agricultural output. They are also facing the depreciation of human capital, massive brain drain and emigration of young people. They have lost control of their banking systems and large enterprises which have been merged into European corporations. Their standard of living is now lower than they had before joining the EU and the gap between them and EU leaders is not decreasing. After the enlargement, the EU found itself in a deep and protracted economic crisis. The enlargement has obviously worsened the situation in Southern European countries as they have to compete with the new members for limited EU resources.

Greece. As a result of the reforms carried out on the EU’s demand, cotton production plunged by half, and production quotas in agriculture hit hard local wine-making. The famous Greek shipbuilding industry has practically ceased to exist: Greek shipowners have purchased 770 vessels abroad since the country joined the European Union. Local experts blame compliance with the EU requirements for creating prerequisites for the country’s financial catastrophe.

Hungary has practically liquidated the production of once popular Ikarus buses, whose output in the country reached 14,000 units a year in the best years.

Poland shut down 90 percent of its coal-mining companies employing more than 300,000 people after joining the EU in 2004. Seventy-five percent of Polish coalminers have lost their jobs.

Poland’s shipbuilding is in deep crisis. The large Gdansk shipyard, which built the largest number of vessels in the world in the 1960s and 1970s, is now divided into two companies that are idling. Dozens of smaller shipbuilding enterprises have had to be shut down and their personnel has left for Western Europe. Poland’s foreign debt was 99 billion dollars when it joined the EU; in early 2013 it reached 360 billion dollars.

Latvia has fully lost its electronic and car-making industries.

Lithuania’s livestock has been cut by four times as local residents have stopped keeping cows following the introduction of milk production quotas. On the EU’s demand, Lithuania has shut down the Ignalina nuclear power plant, thus making itself dependent on power imports (and in need of one billion euros for dismantling the Ignalina plant).

Estonia’s livestock has been reduced five times, with the agriculture reoriented to produce biofuel. The machine-building plant and the Volta plant in Tallinn which used to produce power generation equipment have been closed. On the EU’s demand, Estonia has slashed power generation by almost three times, from 19 billion kilowatt-hour to seven billion kilowatt-hour.

EU membership has hit fisheries in the Baltic States due to EU fishing quotas and so-called “norms of solidarity” in using European water resources.

In 2007, the European Commission fined Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia for attempts to build stocks of food in order to curb prices.

The EU’s association with other states can hardly be viewed as successful.

Even in Turkey, which has drawn considerable benefits from its customs union with the EU, the majority of the population is opposed to deeper integration with the EU. As Turkish Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc noted in his speech on October 17, 2013, the Turks’ interest in EU membership has plummeted to 20 percent from 75 percent five years ago.

UNDERLYING MOTIVES

It is difficult to find the rationale behind such economically defective projects as Eastern Partnership amid the EU’s snowballing problems. Whereas the EU’s rapid enlargement after the breakup of the USSR could be attributed to the fear of a revival of the Socialist empire, the present-day vain attempts to isolate the former Soviet republics from Russia look absolutely irrational. Seeking to prevent at any cost the reanimation of the once-single economic space which had been built for centuries is a recurrence of obsolete geopolitical thinking. It is no coincidence that the Eastern Partnership initiative comes from Poland and the U.S.: Warsaw, seeking to take Ukrainian territories back under its jurisdiction, is lapsing into historical delirium dating back four centuries, while Washington, with its mindset still in the previous two war-torn centuries, is guided by Zbigniew Brzezinski’s Russophobic fantasies.

By many parameters, Euro-Atlantic integration has clear imperial ambitions. Using military force to establish its order in the Middle East, engineering revolutions in the post-Soviet space to plant puppet regimes there, and absorbing former Socialist states through territorial expansion are all means of attaining the goal of geopolitical domination, despite the costs and losses. Such forced integration is unlikely to prove viable in the 21st century. It plunges colonized states into chaos and ruins them, nor does it benefit the mother countries. Although it can bring tangible advantages to their corporations and secret services, its overall economic results are negative, while social consequences fall nothing short of humanitarian catastrophe. This integration continues and will continue as long as other world players agree to finance it, accepting the dollar and the euro as world reserve currencies. Should BRICS countries give them up, the whole Euro-Atlantic expansion, based on military and political coercion, will stop in a flash.

Of course, any integration process is politically motivated as it requires international agreements. But too much prevalence of political motives over economic ones is fraught with major losses and conflicts that undermine the stability of integration associations. Conversely, a political framework for economically advantageous associations secures a natural and stable effect of accelerated development and better competitiveness for integrated countries.

When the common coal and steel market was formed in postwar years under the pressure of European businesses, and later the European Common Market emerged, it brought tangible advantages to all the participants. It helped to build confidence among the parties, while the resulting synergy effect stimulated them to upgrade their integration into an economic union. The politicization of European integration after the breakup of the USSR created imbalances in regional economic exchanges, which resulted in open conflicts between the affected states and the EU bureaucracy. Until recently, the latter used to emerge victorious from these conflicts, imposing technical governments on crisis-hit countries for external governance. But the costs of integration are rising, the EU’s stability is diminishing, and social tensions are growing along with internal resistance to integration. Whereas the “economic phase” of integration benefited all because the synergy effect by far exceeded the losses of individual market participants, politically-motivated integration has caused appreciable losses of whole countries and social groups. Among the losers are Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece, which had stood at the origins of European integration, as well as such backbone social groups as small and medium businesses, civil servants, health care personnel, teachers, students and young specialists.

The European bureaucracy, a new political force with interests and leverage of its own, is behind the emerging EU trend to politicize the ongoing integration. As of now, it comprises some 50,000 officials and hundreds of politicians pursuing their careers in integration. Their policy is largely shaped by trans-European and American corporations dominating on the EU market. Whereas old EU member-states have great misgivings about the expediency of EU enlargement for their national interests, large corporations may benefit a lot from “digesting” the new members’ economies. Transnational corporations have derived much profit by absorbing rival companies in Eastern Europe, cutting labor costs and environmental protection spending, and expanding markets for their products. This explains the growing influence of the European bureaucracy which defends the interests of transnational corporations in conflicts with the local population and national businesses.A DIFFERENT IDEOLOGY

Unlike the European integration where the EU is consistently building its supra-national statehood with all attributes and branches of power, the leaders of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan have agreed to limit the Eurasian integration process to trade and economic issues. The Eurasian integration does not aim to introduce a single currency, form a supra-national parliament or introduce a uniform passport and visa regime. The heads of the new independent states demonstrate wisdom as they avoid politicizing the integration process. Economic expediency is the dominant factor in the Eurasian integration, which guarantees stability of the emerging Eurasian Economic Union. This approach rules out an independent political role for a supra-national body. Its functions should be limited to coordination of decisions with national governments. Such a supra-national body must be transparent, compact and subordinate to the states that have established it.

Mutual respect for national sovereignty is what makes the Eurasian integration different from all previous models, including the European, Soviet, and imperial ones. It is based on the philosophy of Eurasianism, whose basic principles were set forth by 20th century Russian thinkers as they pondered over forms of post-Soviet unification of the peoples of the former Russian Empire.

The groundwork of the Eurasian ideology was laid down almost a century ago by Nikolai Trubetskoi (in Eurasianism and the White Movement published in 1919). In a sense, it was Trubetskoi who created Eurasianism and established the key guidelines of this theory which were later followed up by many outstanding Russian thinkers, from Pyotr Savitsky, Nikolai Alexeyev and Lev Karsavin to Lev Gumilyov. The Eurasian National University in Astana was named after Gumilyov at the initiative of Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev. The Kazakh leader is credited with launching the modern Eurasian integration in March 1994, as he presented a Eurasian Economic Union project in his speech at Moscow State University.

The Eurasian integration ideology rejects foreign diktat, either from a majority of the association members or a supra-national bureaucracy. Its decision-making procedures envision equality and consensus. This creates a solid basis for mutual confidence and optimizes the regulation of the common economic space. Centuries-old cooperation ties predetermine common economic interests and serve as a basis for agreement on supra-national decisions concerning a wide range of issues. In practice, over the five years of the existence of the Eurasian supra-national body, about 2,000 decisions have been made, and it was only in two cases that the parties had major disagreements and failed to make a decision.

Paradoxically, Washington and its NATO allies systemically criticize the Eurasian integration, which they try to defame as “a new USSR.” (As U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in Dublin on December 6, 2012, “The U.S. is trying to prevent Russia from recreating a new version of the Soviet Union under the ruse of economic integration.”) In actual fact, it is the U.S. and the EU that are forcing and cheating the world into accepting their ways in the interests of their corporations. The hysterical response of American politicians to successes of the Eurasian integration, which maxes out whenever Ukraine’s possible participation in it is discussed, shows the ideological weakness of their position. This weakness is compensated for by political coercion and propaganda of illusory values, the most practical of which seems to be the protection of sexual minorities’ rights.

The shaky ideological foundation of the Euro-Atlantic integration will hardly stand further enlargement beyond the present-day boundaries of the European Union and the planned North American Free Trade Zone Agreement (NAFTA). More and more conflicts arise on NATO borders, involving both “soft” and “hard” power tools, as ever new states are herded into Euro-Atlantic integration. This neo-imperial policy has no future in the 21st century. Attempts to implement it entail exponential economic losses which have already generated a blanket zone of social calamity around the Mediterranean Sea, the cradle of the European civilization. Involving former Soviet republics in this process for the sake of their isolation from Russia will create a conflict zone in Eastern Europe with still greater economic losses and social costs.

The failure in the negotiations over the signing of a new Russia-EU Partnership treaty shows that the ideological foundations of the Euro-Atlantic and Eurasian integration are incompatible. Naïve expectations of a large-scale partnership between post-Communist Russia and the EU/the U.S. in the early 1990s have given way to sober thinking as politicians have to come to grips with reality. The Euro-Atlantic integration goes along the line of the well-known British saying “England has no permanent friends, only permanent interests.” As the Eastern Partnership experience shows, the EU does not negotiate but imposes its own rules of integration. They are meant to extend the EU jurisdiction to newly integrated countries and do not envision any talks over rules of cooperation. Associated members have no other choice but to passively obey EU directives. Contrary to this approach, the Eurasian integration envisions joint formulation of the rules of the game. All member-states participate in shaping the legal and regulatory system of integration on equal terms. They have both voting and vetoing rights in decision-making in all issues.

A POSSIBLE RESPONSE

Russia’s foreign policy tradition rules out the signing of treaties discriminating against it. It cannot agree to passive compliance with foreign directives because it contradicts the spirit of the Russian diplomatic school, based on mutual respect and equality of the parties. Since the equality principle does not exist in the Euro-Atlantic integration, it explains the difficulty in the promotion of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s idea to create a harmonious community of economies from Lisbon to Vladivostok. The EU can only interpret it as extending its jurisdiction to the entire territory of Northern Eurasia. This is why the idea of tri-lateral interaction (EU-Ukraine-Russia) is hardly feasible, despite its attractiveness. This is also the reason behind the risk of increased political tension between Russia and the EU over the latter’s attempts to block the participation of post-Soviet states in the Eurasian integration.

A response to the Russophobia of the EU’s Eastern Partnership could be to invite countries discriminated against by EU supra-national bodies into the Eurasian integration. These are, above all, Greece and Cyprus, as compliance with EU requirements means a social disaster for them, without any prospects for pulling out of the crisis. Cyprus has already gone through the default phase and now could be used as a pilot project for transition from the European to Eurasian integration, especially as its economic reliance on Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States has become critical after the bankruptcy of its banking system. Greece is likely to face the humiliating procedure of secularization and alienation of the property of the Orthodox Church and the state in favor of European creditors.

Spiritually, Greece and Cyprus are close to Russia and Belarus; their economies largely rely on Russian tourists and business people. Hundreds of thousands of Pontic Greeks have extensive ties in Russia. Many of these businesses are linked to the Russian market. Lifting the customs border between Greece and Cyprus, on the one hand, and Russia, on the other, would result in an explosive growth of two-way trade, tourism and investment. For Greece and Cyprus, it would open new opportunities to boost the export of their goods and services to the market of the Customs Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan has been actively developing ties with Turkey. Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev has mentioned that Turkey would be a welcome participant in the Eurasian integration.

At this point, the participation of Greece, Cyprus and Turkey in the Eurasian economic integration is unrealistic due to their external commitments to the EU. To accomplish this objective, the first two states must withdraw from the EU, while Turkey will have to quit the customs union with the EU. This may entail their expulsion from NATO. Whereas for Greece and Cyprus these steps would considerably ease their external liability, for Turkey quitting the customs union with the EU may result in the loss of a large segment of the sales market. The EU, if it parts with Greece and Cyprus, will save much spending on loans and refinancing the unrecoverable debt of those countries.

A constructive way out of the growing contradictions between the alternative integration processes in Eurasia would be to de-politicize them into mutually beneficial economic cooperation. But Euro-Atlantic officials do not seem prepared to give up their claims to hegemony in international relations, so this option looks unrealistic at present. It looks like one has to wait and see a worsening of the Euro-Atlantic integration crisis before it becomes possible for countries of Europe and Asia to accept Eurasian principles of equal and mutually advantageous cooperation.