The article is an abridged version of a section of Strategy XXI project. The authors appreciate the ideas contributed by all the participants in the round table discussion “Compromise over the Property Rights between the Elites and Society amid Gross Inequality,” held at the Higher School of Economics on April 24, 2013.

In the 2012-2013 annual rating of the World Economic Forum Russia is 133rd on a list of 144 countries in terms of property rights protection. This hard fact is not just a matter of statistics and certainly it is not confined to economics. At a time when property is not guaranteed, the fundamental incentives that keep the state and society going are wearing thin. People lose interest in creative endeavor, in saving and investing in their own country and in their own selves. Economic activity slows and the impetuses to further growth die down, which is precisely what we are witnesses to in Russia these days.

The illegitimacy of the right to major property (and indirectly any kind of property for that matter) largely stems from the original concept of the privatization of the 1990s, and, to a still greater extent, from the way the concept was translated into reality. Its net effect was very far from creating a massive contingent of shareholders interested in preserving the established property rights. Many petty owners of newly-founded businesses were weak and few – running a small business in Russia proved a really daunting task. As a matter of fact, privatization by and large benefited a handful of big business tycoons with a hot line to the powers that be, while an overwhelming majority of the population were left with bitter and lasting memories of that foul play.

The purpose of creating private property as such was achieved, though. On the list of their achievements over the past ten years the authorities can certainly name an end to the uncontrollable redistribution of assets and the laying of the basis for property rights protection legislation.

However, Russia these days is in a rather precarious position: although formally enshrined in legislation, quite legal private property very often is not legitimate or even considered to be such. The “unfair” procedures that brought about the emergence of mammoth private wealth during the privatization period breeds distrust in the authorities, the laws it adopts, and the measures it takes. Illegitimate property strips the authorities of legitimacy.

LACK OF PROPERTY RIGHTS PROTECTION IN RUSSIA, ITS CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES

People’s striving for wellbeing and prosperity is the key driving force of the economy and society. An opportunity to receive an income and build up wealth is the most powerful incentive to creative activity, although not the sole one, of course. The risk of losing one’s hard-earned income or accrued property erodes or even annuls incentives to hard work, enterprise, investment and build-up of the nation’s wealth.

In history one finds quite a few examples of how uncertainty over property rights and redistribution of assets entailed dire social effects, even disasters. Such redistributions occurred when government institutions were weak amid uprisings, civil wars or other fundamental political transformations. However, even during the periods when the government is ostensibly strong there still exists the risk of property rights getting weak. The oprichnina period under Ivan the Terrible in Russia is one of the brightest examples.

Objective indicators that might reflect the level of property protection in Russia are nowhere in sight; moreover, they are not so important, because the main problems are rooted in perception. As far as subjective indicators – results of opinion polls – are concerned, they are quite telling. According to the World Economic Forum, which regularly questions big industry captains in various countries, Russia in the middle of the 2000s was a very uncomfortable country in terms of property guarantees; and by 2012 the situation got worse and the country plummeted to 133rd line on a 144-nation list (See Fig. 1).

The results of other foreign surveys (3.0 points on a 10-point scale and 121st place in the world in terms of property rights protection from the Fraser Institute; 25 points on a 100-point scale and 136th place in the world from Heritage Foundation) are also discouraging.

At the same time one has to admit that this point of view is that of businessmen and managers, as well as external onlookers. The opinion of Russian people is not that unambiguous by and large. According to a poll by the FOM public opinion studies center of March 27, 2013, 19% said the protection of the right “to the inviolability of property and the home” was good; 21% said it was bad, and 49% described it as satisfactory. It should be remembered, though, that the question was about protection from physical encroachments on property. True, the latter is an important component of a normal climate in society. In the 2000s a great deal was done for the sake of putting an end to the free-for-all struggle for assets (both small and major ones), so Russia these days should not be placed next to the most backward countries. But seizing any significant chunk of property does not necessarily require direct pressures. A person’s legitimate rights may be overtly or covertly reregistered in other people’s names, and in that case protection is closely linked with the opportunities for defending the person involved in confrontation with the law enforcement and judicial systems.

In this field the situation is far worse. According to the very same FOM opinion poll, a tiny 6% believe in the observance of the principle of equality before the law and the right to fair administration of justice – in other words, believe that the rights are protected well enough; another 29% believe that their protection is satisfactory; and 56%, that it is bad. In fact, a majority of the population believes that there is no hope for getting protection of their legitimate rights, including property rights, from the law enforcement and judicial system.

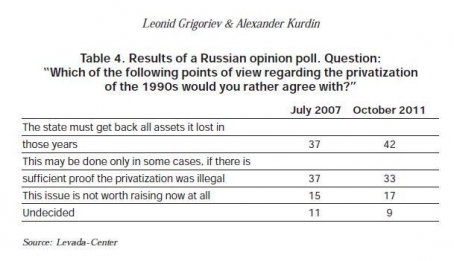

To put it in a nutshell, over its twenty years in transition to a free market economy Russia has failed to bring about a stable system of protected private property. The blame for this should be placed not so much on some malicious designs by the authorities or negligence displayed by law enforcement officials or the judiciary. The roots of the problem are in Russian history, first and foremost, in the design of privatization. It was carried out in a light cavalry charge fashion, without any clear plan or measures to forestall adverse effects. Its chief aim was to break the backbone of the Soviet economy. However, in the end the Soviet economy seems to have undergone reincarnation, at least, in people’s minds and in public sentiment (for details see Table 4 of this section).

The ease and speed of distributing property rights – without any social or investment encumbrances, without building any system of long-term corporate control, without shaping a responsible owner with the use of the stick-and-carrot policy or attempts to form a state ruled by law resulted in success that had no chances to last. There appeared no strategic conditions for a stable system of rights: legitimate major property, a large shareholder class or conditions for small businesses to develop. General chaos and sky-high rates of return, quite typical at a time of the privatization gold rush, were followed by pressures on businesses and the dictating of participation in profits – a kind of “the morning after the night before.”

We are by no means trying to blame everything on the architects of privatization, who acted in the force majeure situation following the collapse of the previous regime. The Soviet system’s downfall was sudden and fast. Neither society nor the class of intellectuals had any time or opportunity to get prepared. The reforms had to be carried out off the cuff. One cannot but wonder that Russia has lived through the revolution of the 1990s without catastrophic cataclysms or civil war. Besides, it is not just the reformers of the first generation who should be held responsible for a situation where nothing has been done in earnest to build a state ruled by law.

As a result, there has emerged the current system of “presumably protected” property rights. The conditions depend on the political situation (first and foremost) and also on the socio-economic trends. Objectively the situation forced successful property owners, even the most patriotic ones, to spend two decades on protecting their rights and incomes through off-shores, to attempt to seize power (like the big business tycoons of the 1990s), or to establish close relations with the authorities, which we are witnesses to these days.

Nobody will be eager to invest, as long as there remains the risk of losing incomes. Nobody will dare leave one’s capital in the endangered zone, if the threat of losing it is real. The simple alternative is to take reserve capital outside of the country, open a parallel business, or invest in foreign properties, but certainly not in industrial activity in Russia. Both small and medium businesses prefer to create stand-by resources instead of re-investing in the expansion of their operations.

Many decide in favor of emigration. Objectively they will be reluctant to invest their capital or effort in Russia and will make no attempts to improve the quality of life in their own country, city or district as long as they have nothing of their own there. In the current Russian realities the export of capital and/or emigration as a means of acquiring relative independence proves a vital need for all those who have any tangible assets, including medium and small businesses, high-ranking managers and those who have intellectual assets, and not just “oligarchs.” Businessmen, scientists and specialists prefer to take to the road.

Uncertainty over property rights pushes the economic system towards the rent-seeking mode of operation. No profit, no innovations. Everything that is necessary for success under such rules of the game fits in perfectly with the standard pattern: grab an asset, squeeze it dry, pay the rent to those who helped and take the capital away. Investment in long-term development is a luxury that only government-run businesses or those affiliated with some influential figure at the top can afford.

But even that system, which some in Russia tend to call state capitalism, is ineffective, because in fact it is oriented not to making profits or achieving social goals, but to security. By virtue of the aforesaid reasons the latter implies proximity to the authorities.

Retaining such connections implies heavy spending on “charity” in the center and locally; this is a sort of “kickback.” In other words, this is tantamount to funneling off the profits that in a normal market economy would maintain investment, growth of share prices and dividends for shareholders or the implementation of really tangible projects. In Russia’s current realities a massive class of shareholders is still inexistent; consequently, there is no control of management – such companies feel free to squander mammoth resources on sports, mass media and security without caring about reinvestment, let alone investment in economically effective long-term projects.

The end effects are deplorable – capital flight and a low rate of accumulation inside the country, the export of cash, ideas and people. Ever fewer private companies go in business. Small and medium ones find it rather hard to take the next step. Their number is shrinking, because borrowing is expensive, and spending on protection and latent payments are high. Part of the funds have to be kept abroad. This combination of factors is the main reason for the falling economic growth rates, both during prime years and the current downturn.

This system of property rights breeds many adverse side effects. Faced with slim chances of getting legal protection of property rights (if at all), private owners have to either resort to corrupt schemes by turning to the very same law enforcers or organized crime for protection racket. Lingering concerns about property safety inevitably leads to the degradation of human resources. The unsettled problem of legal vulnerability and illegitimacy of private property dooms the country to lagging behind in global competition, which is a major problem for national security.WAYS TO PROTECT PROPERTY RIGHTS

In the most general terms there are three ways of protecting property rights that may replace or complement each other.

One implies independent protection of property rights by the owners of assets. First and foremost this requires affiliation with the state, in other words, the very same corruption schemes, including the handover of part of rights to control and manage a business to an official capable of safeguarding property rights. Alongside other negative side effects, this degrades the quality of management. Or part of the profit has to be given away to various racketeers. In fact, this is tantamount to a corruption tax entailing higher prices of goods and services and losses for consumers.

At a time when the state is weak or idle, this independent protection at the level of an individual enterprise, city or region sometimes allows for maintaining business activity. But its effectiveness is very low because it is limited in scale: a large number of minor security systems (from one’s own armed guards to informal contacts with the local authorities, the prosecutor’s office and police) cost businesses a far higher price than one national system.

Another way is protecting property with the national law enforcement and judicial system. These days it is hard to consider Russia as a state ruled by law, because none of the requirements listed below have been met to the full. The requirements are:

- subordination of the state to law;

- independent administration of justice (elimination of mechanisms that turn the judge into an executive official);

- priority of human rights and the enforcement of formal legal equality of all, irrespective of connections to the powers that be;

- guarantees of property and other rights.

The real state of affairs has not moved any farther than the fine declaration that Russia is a democratic federative state ruled by law (Article 1 of the Constitution).

Lastly, there is a third way – protection on the basis of informal norms and society’s deeply ingrained rules of the impermissibility of property rights abuse. This option is tightly pegged to legitimacy, to society’s recognition of the current redistribution of assets. The level of legitimacy in Russia is rather low. This way involves fundamental changes in people’s values and behavior. In other words, it will be very time-consuming.

A combination of the second and third ways looks the optimal one.

Three types of assets possessing specific features can be identified: major government assets, major private assets, and foreign-owned assets.

Major state-owned property enjoys priority and is protected by the authorities and courts, the way it was done in the USSR. Its level of protection can be considered satisfactory by and large. The sole risk is that of latent privatization of some state-owned assets by managers.

The protection of private property in Russia leaves much to be desired. Some unwritten rules are partly to blame for this: massive buy-up of major assets and their return to the fold of the state is perceived by the authorities and the population as success in the struggle against the oligarchs, while in reality each successive change of owners merely triggers a signal to go ahead with the redistribution of assets. Whereas popular masses may welcome this as the transition of property from “hostile” oligarchs to the “friendly” state, from the investors’ standpoint a stronger counter-advertising move is hard to imagine.

Foreign property is under the protection of the outside world, in other words, of foreign interest groups and states. This results in financial “carousels” Russian property owners resort to in order to take funds offshore. Russian capital and profits are then reinvested from offshore zones into Russia. Oddly enough this circulation of capital enhances the level of protection at home. But the repatriation of capital from off-shore zones results in high transaction costs, as bankers and legal intermediaries never work without a commission.

Russia is the sole country where practically all major private assets are offshore-owned. Hence the intention of the political elite to “bring business home,” where it is easier to control. However, property will not come back as long as legal and legitimacy problems are unsettled. Harsh pressures would rather put an end to reinvestment in the country and trigger capital flight.

By virtue of some peculiar features of Russia’s socio-political model following the breakup of the USSR society and the establishment are dangerously alienated. Three basic compromises are essential to creating an environment favorable for national development and success. Firstly, there must be a compromise between the groups of the ruling elite – the group with a background in law enforcement (currently political), rooted in the Soviet bureaucracy and tradition, on the one hand, and the financial group, which emerged mostly during the economic reform of the 1990s, on the other. Secondly, a compromise between the ruling group as a whole and the active part of society (the “creative class”). Thirdly, a compromise between Russian and world elites over key property and security issues in the country.

Should this triple compromise be achieved, everybody will stand to gain. The financial elite will at last achieve a relatively stable position, shrug off the need to seek protection from law enforcement agencies and will be able to invest not in security, but in business. The political elite will benefit because the financial elite will consolidate the center of its economic interests in Russia, thus providing for economic growth and, consequently, overall stability. Besides, the country and its leadership will improve their image in the eyes of the outside world, which will certainly help draw investment. The creative class will acquire the certainty it will retain its modest property rights and, what is more important, will be able to feel friendly changes in the environment enabling the individual to display one’s potential. The population in general will feel the advantages of the improving institutional environment, growing capital investment and faster economic growth.

THE CURRENT STATE AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE LEGAL SYSTEM

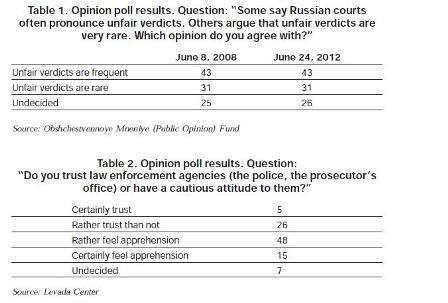

Ensuring an acceptable level of protection for property rights and the entire spectrum of Russian citizens’ rights in general will require a targeted policy. The current condition of law enforcement is well seen in the findings of public opinion polls – the fairness of court verdicts and the activity of the police and the prosecutors’ offices are looked at skeptically (Table 1 and 2).

Regrettably, Russian society is not yet prepared for the voluntarily observance of the rights of citizens, including property rights. For this reason this right will be observed only because the state authorities with their compulsion machinery regard its observance as their priority. Transition to a state ruled by law requires an effective compulsion mechanism. This is the reason why the law enforcement system – courts and police (as well as prosecutors, investigators, etc.) should be the focus of attention.

The effective operation of the law enforcement system can be established within relatively short deadlines. Policies in this sphere should have two aspects.

Firstly, strict control of the observance of high standards of operation of the entire law enforcement system on the condition it enjoys the necessary resources. The responsibility of law enforcement personnel for abuse, let alone for crimes, must be immeasurably higher than that of ordinary citizens. Guarantees of a decent standard of living are a mandatory compensation for this. Attempts by the authorities of any level to put pressures on courts and police should be treated with extreme intolerance.

Secondly, the transformation of the law enforcement system must be public. A non-transparent and unclear system will always cause distrust, while the openness of law enforcement agencies will enhance the employees’ incentives to doing the job properly and their credibility with society. Even if the first phase highlights some deep problems, driving the disease inward is no longer possible.

Anti-corruption policies retain the indisputable priority. A number of measures are being taken, trials are underway, but this policy needs to be made systemic, anti-corruption cases must result in verdicts, prosecution must be indiscriminate and participation in international initiatives made standard practice. In a global world international cooperation in the struggle with corruption has no alternative.

THE INEQUALITY PROBLEM

The high level of inequality in Russia is a major obstruction in the way of creating new informal institutions and promoting values that would allow for legitimate major private property. In the final count, towards the end of the 2000s, when Russia’s GDP achieved the parameters of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) within the Soviet Union, it turned out, as follows from the findings of a conference at the Higher School of Economics, that a tiny 20% of the population “successfully participate in raising the level of wellbeing, which became possible with the emergence of a market economy.” The third quintile have just achieved the level of 1990, and 40% of the population “earn less than before the beginning of the reforms.”

Discrepancies in the levels of income and wealth – extremely great and perceived as unfair – undermine the legitimacy of property. Those people who look at this inequality from below upwards would stay rather calm at the sight of re-division of property rights – if they have nothing to lose by and large. Moreover, there may emerge some reasons for encouraging such a re-division: personal risks are far smaller than the expected benefits from participation in such redistribution. In the meantime, incentives to spending effort and time on one’s own development are rather low, because, as experience shows, the distribution of incomes and wealth does not depend on it.

What is to be done to straighten things out?

- Create incentives for the middle class and the poor to gaining material wealth through creative activity without participation in the redistribution of property;

- Guarantee small and medium businesses certainty about the future;

- Create incentives to home-building and give the middle class a chance to have a home of one’s own;

- Stop the process of redistribution in favor of the poor classes to the detriment of the middle class;

- Promote the involvement of the upper and middle class and industrialized regions in competition for positions in the world;

- Enhance the stability of jobs for the middle layer of the middle class and expand this social group with school and university teachers and medical doctors;

- Promote the spread of equity ownership to large public and private companies among households; create mass ownership of financial assets by the middle and upper layers (25% of the population) of the middle class, including shares of major national enterprises (to increase the share of stockholders from 1-2% of the population to at least 15%);

- Expand the stable middle class (in terms of savings) by 2030 from 25% to 35%-40% of the population.

LEGITIMIZATION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY

How legitimate private property really is as a phenomenon and an integral part of a market economy can be well seen in Levada Center polls “What economic system do you find most appropriate?” The polls have been conducted annually for a period of fifteen years. The respondents are asked to choose between two answers: “The one that is based on government planning and distribution” and “The one that is based on private property and free market relations.”

The first reply – in fact, the one in favor of a controlled economy – has been invariably in the lead; throughout the 2000s its share was invariably above 50 percent, and its edge over the alternative has never been less than 15 percentage points. Only on one occasion, at the beginning of 2012 the gap narrowed (49% to 36%) but at the beginning of 2013 the ratio swung back to 51% against 29%.

It is rather amazing that in the context of such sentiment in society the market economy model is still being implemented, at least to some extent, and private property remains. However, there is a possibility that on the condition of (a) the emergence of some anti-market political force and (b) the observance of the principles and procedures of democracy the fundamentals of the market economy and private property in Russia may be cardinally revised. In other words, there will occur a shift towards socialism – in fact, another socialist revolution.

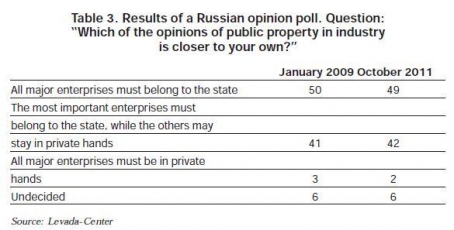

Other results of opinion polls held over the past few years also indicate Russians’ mixed attitudes to private property and privatization, including preparedness for a revision of privatization results of twenty years ago (Table 3 and 4).

The ideas of getting rid of at least the unsavory taste left by the privatization are widely spread among the people and inside the political, financial and intellectual elites.

In any case, restoring public ownership of assets – partial re-nationalization – would most probably stall development along many lines and would result in the loss of effectiveness, in growing investment into doubtful PR mega-projects, and a decline in investment in useful undertakings.

Quite popular is the idea of a compensatory tax, already articulated by Vladimir Putin, Grigory Yavlinsky, Mikhail Delyagin, Mikhail Khodorkovsky and other politicians and economists upholding different views. But a one-time compensatory tax will not be a plausible solution at least because its size, the taxable base and the range of payers cannot be agreed, even if the very idea of a compensatory tax gains wide popular support. The proper moment for introducing such a tax is long gone. Discrimination against private property by establishing arbitrary taxes for an arbitrarily determined range of persons would banish businesses and spark a conflict with the whole world.

The conclusion is simple: ways to legitimize large private property in the eyes of the population in the foreseeable future (say, in ten years’ time) just do not exist. Only time and habit will help.

Nevertheless, already now efforts must be exerted along several lines:

Firstly, it is necessary to put an end to discussions about the very possibility of revising the results of privatization, including the introduction of compensatory measures for “ill-gotten” wealth. If the state is to make the rich pay, it might be possible to impose progressive taxes on incomes or property, but not link them with privatization. Otherwise, the idea of property rights’ inviolability will be never ingrained in people’s minds.

Secondly, time is ripe for terminating lawless redistribution of property. According to a Levada-Center poll of May 2012, 72% of the polled believe that the property privatized in the 1990s is not returning to the country or the people but is merely redistributed inside the ruling elite.

Thirdly, measures must be taken to smooth over public discontent and improve the image of property owners. This is a competence of not so much the government machinery as privatization beneficiaries. There is to be a “positive program” for the country and the people, voluntary self-restrictions on consumption by the political and financial elites, and their active involvement in social projects (including charity and sponsorship). All this will surely not legitimize private property overnight, but may help prevent the discontent from entering an active phase.

Fourthly, the issue of forming a large class of shareholders deserves special attention. An overwhelming majority of people do not have even the slightest stakes in enterprises of national importance, which causes estrangement. Spreading equity ownership among various groups of the population would help overcome the gap in interests and values between a handful of property owners and the dispossessed majority.

The policy of the state aimed at establishing the rule of law, in conjunction with measures for the gradual legitimization of major private property, may in the long run yield the desired effect. This is a long-term program that does not admit of any change of the mainstream development vector.