This article summarizes key points made in their recent book Alarming Contours of the Future, published by EKSMO (2015).

We are living in an amazing time of change. After the turbulence of the 1980s and the crises of the 1990s, it seemed finally that Russia had weathered the storm and was in for a predictable voyage. Yet the country is still struggling for a place in the world.

Exhausted by the Cold War, Russian civilization retreated for twenty years. In 2014, Russia stopped retreating, but the West did not stop advancing. The ensuing collision divided Ukraine and caused bloodshed in Donbass.

We are living at a time when it is particularly important to understand where the world and our country are moving. Will Russia pass through the dangerous rapids without significant losses? Of course, life is more complicated than we think it is. But any future consists of the possible and the impossible. If we remove the latter, we see the contours of the former.

Trends in economic and technological development, and political and socio-cultural processes predetermine an overwhelming majority of international events. Many demographic and economic trends are long-term and easy to extrapolate, especially within a relatively short period of time. The geographic location of a country also dictates certain limits of behavior. Countries are not free to choose their neighbors or move seas and mountains. Nations cannot relinquish their culture, history, or religion. Conflicts over resources and influence continue for centuries. Behavior in the past shapes behavior in the future.

Winston Churchill was not the first to notice that “the farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.” The logic of many processes is cyclic. Good harvests are followed by bad harvests; empires rise and fall; and the left and right alternate in power. Aging leaders will not remain forever; election cycles occur every four to five years; and negotiations in any case produce a result – either positive or negative. By singling out several anticipated crucial events and monitoring their decreasing or increasing likelihood, we can see how the international situation might change.

Still, however adept we may be at planning, life springs surprises every day. People make mistakes and revolutions suddenly sweep away governments. No one could foresee scientific discoveries that have dramatically changed the world. Volcanoes and viruses do not ask for permission to strike. Last year alone produced several big surprises, such as Crimea, Ebola, and the Islamic State. We can only hope that surprises will not upset all our forecasts completely.

How to prepare for the future?

The current international situation can be viewed as an accumulation of problems attesting to a change in the paradigm of global development. We are witnessing the progressive decay of the economic and political system created by the United States and its allies after World War II.

The exhaustion of the growth potential in the current technological cycle and the birth of a new order are fueling major changes in the global economy. The contemporary technological and economic cycle, in which wealth was effectively created in sectors concerning information technologies, pharmaceuticals, and energy, is gradually giving way to a new cycle where demand will be the greatest for bioengineering technologies and smart information networks. However, while the leading industries of the global economy are slowing down, new industries are not yet capable of generating large revenue streams. As a result, businesses, governments, and ordinary citizens are doomed to fight for a share of the pie, which is not growing fast enough.

The international system has been faced with a host of crises, varying in nature, depth, and intensity.

Firstly, we are witnessing an aggravation of the institutional and political crisis of Atlanticism as a system that still claims to govern a growing “non-Atlantic” world. As a result of universal globalization and emancipation, the organizations that set the rules of the game in the economic and security sectors – the World Bank, the IMF, and the UN Security Council – do not reflect the real balance of power. Independent regional players, such as Iran, Turkey, India, Brazil, South Africa, and others, are gaining more and more weight. The struggle to redistribute economic and political influence is increasing international tensions. Attempts by the U.S. to retain its global dominance and control over the periphery of its rivals are adding fuel to its confrontation with China and Russia.

Secondly, the global legal order is eroding, and the sovereignty of states is weakening or being deliberately undermined. The U.S. is boosting its efforts to impose the extraterritoriality of its police and judicial systems on the world. The principle of the inviolability of borders has come into question. As a result, the number of unrecognized states is increasing. Growing differences among leading world powers have paralyzed the UN system.

Thirdly, international relations are becoming increasingly more regionalized. As the dominant center of power decays, alternative organizations – BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization – are gaining strength. The more active role global corporations, non-governmental organizations, and individuals play in the global media space make international relations multidimensional.

The fourth tendency is the intensification of struggles over national and religious identity and self-determination, as well as the redrawing of borders along ethnic and religious lines. There are a growing number of conflicts under ethnic and religious slogans. Europe is at an impasse of secular tolerance. The Russian Orthodox Church is looking for a mission of its own. In the U.S., conservative Protestant movements have reshaped the Republican Party. Iran, Turkey, and radicals from the Islamic State are competing to determine the future course of Islam. Africa is becoming a new battlefront of religious conflicts.

There is an obvious crisis in the global development model. Economic growth is slowing as the potential of the previous technological cycle is eroding. Structural unemployment is growing. The economy and human behavior have changed, but a new model of sustainable growth has not been found yet. Communism lost the battle for the minds of the people. The Asian “export” model, whether Chinese-style or another version, will not likely survive one more generation. The liberal model of the Washington Consensus works only in the U.S. and only while more banknotes are printed.

The fifth tendency is the shift of the world’s economic center to the East, the erosion of the influence wielded by the U.S. economic system, and the decreasing weight of its basic elements – the dollar, control over global finance, and leadership in technology and education.

The growth of competition between the U.S., the European Union, China, Japan, and other economic centers has exacerbated the struggle for control of markets and major resources – human potential, energy, clean water, arable land, and a business-friendly environment. By seeking to create the Transatlantic and Trans-Pacific Partnerships, the U.S. is moving away from the universal trade regime and seeking to change international economic ties to meet its own interests and to sideline rivals, especially China.

The sixth tendency is growing social pessimism and social tensions. Inequality is rising rapidly. In leading industrial countries children already live relatively worse than their parents. There is a deepening conflict between governments and their citizens over the distribution of diminishing incomes. While people demand justice, governments are trying to establish total control over their citizens, especially over their finances. In the short term, we will see first sporadic and then organized protests against the dominance of the Big Brother. Julian Assange and Edward Snowden are just the trailblazers.

There is an evident crisis of ideologies. While the majority of the world’s population demands justice, the “golden billion” continues to impose the concept of individual freedom increasingly devoid of responsibility and turning into all-permissiveness. The political center, the product of a strong “middle class,” is eroding, and radicals and populist demagogues are taking over the media. A completely new generation, whose conscious experience is linked to Facebook, will enter the stage in a few years. It is hard to predict in what way they will affect politics.

While the “lower classes do not want to live the old way,” the “upper classes” of the West are still “drifting with the current.” There is a clear crisis in leadership. The seventh tendency is bureaucrats in Europe who came to power through the system built in the “fat years” and who continue to avoid making knowingly painful decisions. The U.S. political elites are gridlocked. The U.S. foreign policy bureaucracy has been in autopilot mode ever since the Cold War. However much the Group of Seven may bustle about, the real domestic and foreign policy initiative belongs to the leaders of the “rest of the world” – Modi, Xi Jinping, Erdogan, Putin, Rousseff, and Widodo.

The international community’s problem is not so much in the acuteness of crises as in their global nature. As crises pile up, they create a situation that goes far beyond the capabilities and competence of national governments. Making decisions in line with their understanding of their interests, the authorities of each country often aggravate the situation for their neighbors. The struggle for influence among countries and blocs, the weakness and partisanship of international institutions, and the novelty of many problems prevent the development of effective responses to increasingly acute challenges.

Every new crisis creates a large number of dissatisfied and often angry people. These people, who consider themselves victims of those who rule, will not fail to get together: either as small groups of protesters or, eventually, as large organizations with talented leaders.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, who is not known for emotional statements, has described the next few years as revolutionary. But is a revolutionary burst inevitable? Will the world be torn apart by a new armed conflict under the burden of its tensions? While recognizing the presence of many conditions for a revolutionary scenario, we instinctively want to believe that it can be avoided. However, this faith is not supported by our historical experience. Profound changes in the global balance of power rarely take place without armed conflicts. No one wants to risk war. No one wanted it in 1914, either. But the logic of a public conflict puts politicians in a situation from which they see no other way out. Even if the existence of nuclear weapons keeps major powers from reckless moves better than ever before, rivals will not stop looking for ways to resolve their disputes and settle scores using all the available means, directly or indirectly. Not surprisingly, war involving all available means – “a multidimensional war” – has become the latest word in military art. It involves a new arsenal of information, political, financial, economic, and other measures to stifle the enemy.

Russia at the epicenter of a global hurricane

Russia has not yet fully felt the effects of stagnation, economic sanctions, and falling oil prices. Even if the government fulfills its budgetary commitments, the impact of inflation and difficulties in financing the bulk of businesses will soon become a hard reality. However, Russia has not yet been able to develop a forward-looking policy because of conflicting interests between the economic elite that formed in the early 2000s and the interests of Russia’s long-term development as an independent industrial power. Forces that view the national interests of business and society as a whole in the accelerated re-industrialization of Russia are gradually gaining political weight. A struggle is underway between elite groups advocating “liberal-financial” and “industrial-state” models of development.

The open conflict with the West and, especially, the fact that the economic war against Russia has highlighted the urgent need for economic diversification and financial sovereignty, has seriously exacerbated the conflict and moved it to the foreground, giving it a purely practical, political, and media dimension. In the next few years much will depend on how this conflict develops.

Any national leader wants to leave a country more prosperous than it was when s/he came to power. The Russian authorities have succeeded in that for the last 15 years. But the temptation to achieve quick tactical successes should not go to their heads and destroy the prospects for a strategic victory. For Russia, the formula of such a victory is continuous and stable development for at least 20 years more.

Historical experience makes Russian society and the elite resistant to ordeals. The creation and preservation of the world’s largest country in a tough competitive struggle is an indisputable achievement of the Russian people.

Russia’s strategic vulnerabilities

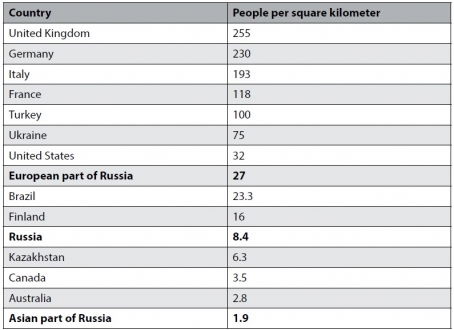

However, apart from its unique advantages, Russia has some vulnerabilities. In contrast to all developed countries, Russia has a very low population density (8.4 people per square kilometer, compared to 130 people per square kilometer in Europe). In order to understand the importance of this figure, imagine what 130 and eight people can do with their own hands on one square kilometer during a year.

Russia has always had large distances between cities and towns, no natural barriers against invaders, vulnerable communication lines, a northern climate, and a short growing season. Many regions of the country are not suitable for agriculture, and the main production centers are far from energy sources. The government must ensure security and maintain uniform social standards in the health and education systems in eleven time zones from Magadan to Kaliningrad. Finally, Russia’s industrialization in the 1920s-1940s was not carried out in a market economy, but in a planned economy.

All of the above factors make the country fragile, the production of the marginal product difficult, and social changes slow. Nineteenth-century Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov rightly wrote that “geography is the stepmother of Russian history.” The special type of statehood in Russia that has developed over centuries and which emphasizes the centralization of resources is fundamentally different from the classical European market type. This factor makes disagreements between Russia and European states on a wide range of issues inevitable in the future.

Table 1. Population Density

Over the past three centuries, Russia has been the main dynamic core of Eurasia and the center of attraction for its neighbors. Russia was one of the first nations to bring the fruits of European culture to the Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Russian Far East. But Russia will not determine the future of Eurasia in the twenty-first century on its own, since it will have to compete with China, the EU, the U.S., Turkey, and Iran.

Russia’s demography will be the main challenge. No matter how successfully the Russian economy and technologies may develop, everything will be in vain if the Russian population continues to decline. This is why a demographic criterion is key in evaluating the performance of heads of Russian regions.

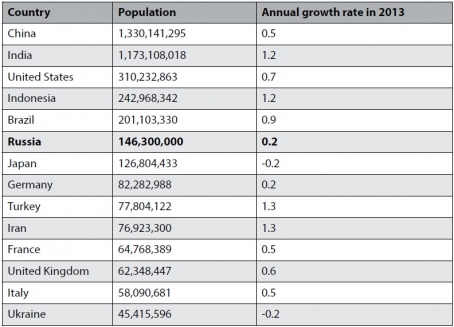

According to a demographic forecast by the Russian State Statistics Service (Rosstat), one of the following three scenarios may take place in the country in 2020: a “low” scenario – the population will decline to 141,736,100 people; a “medium” scenario – a small increase to 144,473,400 people; and a “high” scenario – an increase to 146,939,400 people. Considering the reunification of Crimea and Russia and provided that an upward demographic trend persists, the “high” scenario may take place and even exceed the forecast. However, this is not enough. Russia’s successful and sustainable development requires a population at least twice as large. This problem could be solved gradually if the population grows by 0.5-1 percent annually. At present, the population growth rate stands at 0.2 percent.

Table 2. Number and Annual Growth Rate of Population

Source: World Bank, Rosstat, 2014

Russia’s key priorities until 2020 will include boosting the birth rate and reducing mortality, especially among the working-age population. According to official statistics, 49.8 percent of deaths are caused by circulatory diseases; 15.3 percent by neoplasms, five percent by digestive system diseases; and four percent by respiratory diseases. Another 1.5 percent of deaths are caused by traffic accidents. Russia wants to decrease mortality rates not so much through the modernization of the healthcare system, as through the promotion of healthy lifestyles – sports, healthy eating, and abstinence from smoking and alcohol, especially while driving.

Another important source for the renewal of human capital is the assimilation of migrants. Russia will continue to be the world’s second center of attraction for migrants, after the U.S., and their assimilation will account for half of the country’s population growth until 2020. In 2015-2016, this process may increase due to the mass emigration of Russian-speaking families from Ukraine to Russia.

Finally, the last major indicator of public health will be a consistent growth of GDP per capita. In 2015, Russia, for the first time in its history, has reached the recommended medical standard for meat consumption (75 kilograms per person per year). The importance of this and other similar indicators should not be underestimated. The continuous growth of per capita GDP in the U.S. since the 1880s has led to the emergence of a model prosperous society, which lies at the heart of U.S. soft power. In 2014, Russia’s GDP per capita (U.S. $14,612) was higher than that all other post-Soviet countries and many countries in Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland and Hungary. Until 2020, Russia will try to restore a GDP growth rate of above three percent, bring it to the U.S. level of $20,000 per capita, and subsequently catch up with Italy.

Russia’s domestic policy until 2020

Russia’s strategic objective in its domestic and economic policies until 2020 is to boost the economic growth rate from three to five percent annually. In 2014, the federal government announced a new liberal economic program aimed at encouraging small and mid-sized businesses. If this program is successful, small entrepreneurs could account for up to 50 percent of GDP by 2025 (compared to 20 percent in 2014). This will help accomplish the major federal task of creating a self-sufficient economic model with exports making up less than 20 percent of GDP (the current level is 28.5 percent). As a result, the economy will overcome its excessive dependence on energy prices.

The Russian authorities still have many important, but unused tools. Apart from the liberal economic policy and dirigisme in some issues, Russia has still not tapped an important, yet dangerous, development resource – public enthusiasm, which helps achieve soft mobilization of resources by fostering social energy in the name of a “just cause.” In Russia, mass enthusiasm has always implied freedom and justice. In modern conditions, enthusiasm can set moral benchmarks for Russian society, which should be tied with the goals of Russia’s development. In the 1990s, countries in Central and Eastern Europe carried out the social and political transformation of their societies in this way by “joining Europe.” In China, the idea of creating a “moderately prosperous society” motivates the Chinese masses to work hard. New frontiers for Russia may include the development of Siberia and the Russian Far East, economic growth, doubling GDP per capita, higher birth rates, space exploration, and technological leadership.

For the first time in Russian history, new frontiers should be internal, rather than external. The return of a national development idea will help the country overcome the divisions in society that occurred after the October Revolution and the Civil War in the early twentieth century. Russia should also take into account the negative results of the communist experiment and avoid imposing categorical assessments on society and the individual.

For the sake of development, consumer-oriented attitudes of popular culture should be amended. Emphasis should be given to family values, a socially healthy individual, and relations based on honesty and trust. The state must ensure safety and equal rules for all citizens. Fighting corruption, the arbitrariness of officials, and excessive state control should become a vital priority. Federal policy should be aimed at reducing stress for citizens and economic agents. These measures will help renew the social contract and restore people’s self-confidence.

As mentioned above, the main condition for this scenario is peace and internal stability in Russia. This condition can be met only by a strong government, which many in Russian society desire. It is very likely that Vladimir Putin will win the next presidential election scheduled for 2018. In this case, a consolidated elite will remain in Russia until 2024 and seek to accomplish national development tasks.

How will Russian elites behave if the conflict with the West continues? If the declared liberal program succeeds, external pressure will not have any significant impact on domestic processes in Russia. But if it fails, structural problems at three levels may make themselves felt.

Firstly, the struggle may intensify between the “status quo” elites, who advocate the preservation of a liberal financial economic model, and groups that favor an industrial state model. Ideally, their interests should be harmonized to achieve balanced development.

Secondly, like in the 1990s, the national economic and political elites and ethnic and regional groups might resume their struggle for power and economic influence. Russian federalism is still evolving, and the current trend is to transfer more powers to the regions. However, this process is not irreversible.

Finally, if Russia’s confrontation with the West escalates and the federal government’s liberal economic policy fails, Russia may return to the mobilization variant of development. This will be a forced scenario, but Russian leaders are already considering it a possibility.

Until 2020, the centrist platform formed around Putin will stand out among major political forces in Russia. Since this includes leading liberal and conservative forces in Russia, prospects for a liberal opposition will remain illusory. Ethnic Russian nationalism will remain the only potentially influential force. But its rise to a noticeable position is possible only if the social situation in the country worsens and the central authorities lose their grip.

Russian foreign policy until 2020

Since Russia has all the potential for development, the main goal of foreign policy until 2020 should be to block external negative influences and avoid involvement in long-term confrontation with its rivals.

Sources of external threats to Russia will remain the same – Islamism from Syria and Iraq, drug trafficking from Afghanistan, a possible escalation of conflicts involving Nagorno-Karabakh, North Korea or Iran, and the civil war in Ukraine. The priority of maintaining strategic stability with the U.S. requires that Russia modernize its armed forces, military-industrial complex, and global navigation and space communication systems. The need to respond to external threats will divert resources, and Russia’s weakened ability to project power and exert influence in neighboring countries will affect its national development.

Before 2020, Russia will cease attempts to save the “Soviet legacy” in other post-Soviet countries. After the Soviet Union’s breakup, major infrastructure facilities that were vital to Russia remained in Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan (pipelines, railways, ports, military bases, a space launch site, and production facilities). For 20 years the logic of Russia’s policy was to remove the main objects of Soviet infrastructure from the influence of hostile neighbors and establish preferential relations and alliances with friendly countries such as Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Armenia. Simultaneously, Russia sought to reduce its dependence on Ukraine by building alternative pipelines bypassing Ukraine and a new base for the Black Sea Fleet in Novorossiysk, and placing arms contracts with Russian, rather than Ukrainian, companies. After the incorporation of Crimea, Russia no longer has vital interests beyond its borders: the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, Baltic cargo ports, or Belarusian railways cannot serve as pretexts for Russian claims. Russia would be forced to intervene in the affairs of other post-Soviet countries only if Russian communities there are repressed. In all other cases, Russia will avoid getting involved in conflicts along its borders.

Although by 2020 Russia will not become a leading world power, alongside the U.S. and China, the future of international competition will depend on its choice of partners. Russia will become a strategic balancer interested in preserving the independence of its policy and international assessments. Reluctant to alienate Russia in the future, the West will be more attentive to Russia’s interests.

While strengthening its international position, Russia will seek to expand the membership of the Eurasian free trade zone by engaging neighbors and other friendly countries, such as Turkey, Iran, Ukraine, Vietnam, India, and countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus. If the BRICS association maintains consensus on the principles of global development, it will gradually become a center of power comparable to the Group of Seven because of the slow erosion of the latter’s unity on international and economic issues.

Cooperation with China will become an important external source for Russia’s development. China’s Silk Road Economic Belt transport initiative, covering a territory from China across Central Asia and Russia, will be a key project between the two countries. Simultaneously, Russia will seek to complete the European-Far Eastern transit project based on the Trans-Siberian and Baikal-Amur railways. These two transport projects can generate revenues comparable to those from the sale of energy resources. Predictions of a Chinese demographic expansion into Siberia and the Russian Far East will not come true, and the number of Russians crossing the Chinese border in 2020 will still be larger than the number of Chinese crossing the Russian border.

The Arctic will remain a priority area for technological and energy cooperation between Russia and the West. A resumption of full-fledged dialogue between Russia and the U.S. will help revive cooperation between the two countries’ leading energy companies.

A better future for Russia in 2020 might mean the following: no international conflicts, political stability, population growth by 0.5-1 percent per year, employment of over 60 percent of the working-age population, annual economic growth of 3-5 percent, and exports accounting for less than 20 percent of GDP. Achieving these targets would help Russia safely make it through the crucial years of 2015-2020 and firmly secure its future.

Success depends on adaptability to change

By 2020 a new national business elite will take shape. Its consciousness will be based on today’s competitive realities in Russia, rather than on the past experience. At the same time, the generation whose ideas and interests were rooted in the Soviet or transitional periods will gradually fade from the political scene. The outcome of Russia’s development will depend on the ability of Russian elites to realize the depth and revolutionary nature of the required changes, to correctly identify factors of the country’s success in the new world, and to mobilize the potential of the nation.

Russia was a good student at the international school of conduct according to the Yalta rules, even if it had no friends there. Yalta recognized that all players had their own spheres of vital interests and adopted corresponding rules of the game. But everything comes to an end: you cannot violate the spirit of the law, while demanding compliance with its letter. It is symbolic that the era that began in Crimea ended in Crimea as well.

Until the current Western leaders publish their memoirs, it will not be clear whether the attack on Russia is only an attempt to teach it a lesson of obedience, or whether it really is the last desperate attempt to prevent a “mutiny aboard ship” and keep the global system under Western control. We have a feeling that the West and the rest of the world have already passed the point of no return in their relations. Now no one will force countries like India or Brazil to sacrifice their own national interests. Together, China and Russia, even weakened by the crisis, are invulnerable to the U.S. The more effort the U.S. and NATO take to isolate and demonize Russia, the more obvious the limits of their influence will be.

In any case, if Russia holds out until 2020 and all attempts by its enemies to bring it to economic collapse, chaos, and disintegration fail, then we can be certain that the era of Western dominance has ended. Thus, international relations will officially enter a new era.