Foreword

Two hundred years ago Europe – then the undisputed centre of the world – stood on the threshold of a new historical era. A series of political, social, and ideological storms had shaken the Old World since the last quarter of the 18th century, triggering wars, which engulfed all of the leading European nations. The Congress of Vienna remained in session for many months – its activity suspended for a time by a new outburst of military action – seeking a new order for the continent’s development. Heads of state and diplomats sought to create a system of international relations, which could manage the conflicts that arise inevitably between major states, while avoiding head-on collisions and minimising damage. The changes that had to be made in the structure of states spawned numerous threats to stability from new players operating outside the system.

The significance of the time went far beyond diplomacy. The world stood on the threshold of profound changes in the nature of society, technology, and the economy. Ideas were already taking shape that would play a critical role in mankind’s history through the 19th and 20th centuries. Perhaps most important: centre stage would now be taken by nations and peoples, increasingly aware of their own interests and their ability to make history, and no longer willing to submit unquestioningly to rulers and their political states.

None of the emperors, chancellors and ministers who gathered in Vienna could have foreseen what was in store for the world five, ten, thirty, and a hundred years into the future. But they understood their responsibility and felt the burden of time, which made stricter demands than ever before on those who presumed to determine events.

More than fifty years later the great Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, whose deep interest in the philosophy of history is well known, would address the period that culminated in the Congress of Vienna in his great novel War and Peace. Tolstoy refused to accept that history is made by individuals, but he also rejected any fatalistic belief in divine determinism, instead seeing the roots of historical movement in the totality of the strivings of millions of people. “For history, there are lines of movement of human will, one end of which are shrouded in the unknown, while at the other end people’s consciousness of their freedom in the present moves in space, in time and in dependence on causes”, Tolstoy wrote. The dialectic of freedom and determinism, of what we can change and what is objectively inevitable lies at the heart of Tolstoy’s novel and his perception of history.

This perception looks surprisingly modern today. Perhaps because, 200 years after the end of the Napoleonic wars, humankind finds itself in a place that is similar. There is a general understanding that fundamental changes are underway, but no one is yet able to grasp their nature or to sketch the outline of a future. Everyone wants peace, but each has his own idea of what “peace” means. And players operating outside the system are ready to seize opportunities, which this historical break presents. DAISH, a structure that aspires to a complete overthrow of borders, political systems, social relationships, and values, has bared its teeth to the world.

Tolstoy believed that the historical process is objective, non-linear and irreversible. It cannot be stopped at a particular point for someone’s benefit. In other words, there is no “end of history”. The historical process consists of the hopes and passions of millions of people, its driver is “a force equal to the momentum of nations” (what we might today call “increasingly diverse polycentrism” or “democratisation of the international environment”).

Times of change are always associated with uncertainties, risks and opportunities. At such moments the price to pay for a mistake increases dramatically. Many processes and events, of prime importance at other times, become secondary, and age-old issues of policy and diplomacy, of war and peace, take centre stage. It is critically important to understand the logic of history; the challenge for the leaders of countries, working within this logic, is to ensure the survival of humanity, the maintenance of peace and strengthening of the foundations for progress worldwide.

Policy objective

Moving away from the illusions of the 20th century, the policy objective today is the prevention of hell on earth, rather than the creation of paradise. Recent military, political and economic crises show that maintaining stability is no easy task, even in traditionally calm regions, such as Europe and North America. The destructive nature of global experiments – the military-political missions of Communism, Liberalism, the Caliphate, or any other dogmatic ideologies – has become evident.

Competition between the major powers, provocative action by medium-sized and minor countries, and cross-border challenges remain the main sources of global threats. They require thought-out and agreed positions. However, the world powers exist and develop in extremely different conditions. Although we live in the era of global communications, the powers fail to hear and understand each other. This entails a risk that countries’ interests will be inadequately understood and that threats to mutual security will arise. Attempts to build relations on ideological, rather than pragmatic foundations invariably lead to a dead-end of violent escalation. Foreign policy loses its way and wars are the result.

What we now have is a “Hobbesian” moment: not only (one might even say “not so much”) a growing number of increasingly varied conflicts and wars, but, specifically, the inability of the leading players to agree on rules for interaction. An ongoing “game without rules”. The opinions of the leading centres of world power as to what is allowed and what is prohibited – about the basic rules of international life – differ, and sometimes diametrically. The fight against extra-systemic threats, weakening of traditional rivals, ideological fervour and the promotion of geopolitical interests form a tangled skein of contradiction and double standards, where the attempt to achieve certain goals undermines the possibility of attaining others.

At the same time, we all have the same primary interests: keeping the peace, resisting instability (particularly that caused by increasingly virulent terrorist structures) and creating the conditions for sustainable development. These tasks are only possible if the global powers can find consensus on their behaviour towards each other and the use of force. There is no other alternative in the modern world. Or rather, the alternative is to see global politics plunge into a vortex of uncontrolled escalation in all directions.

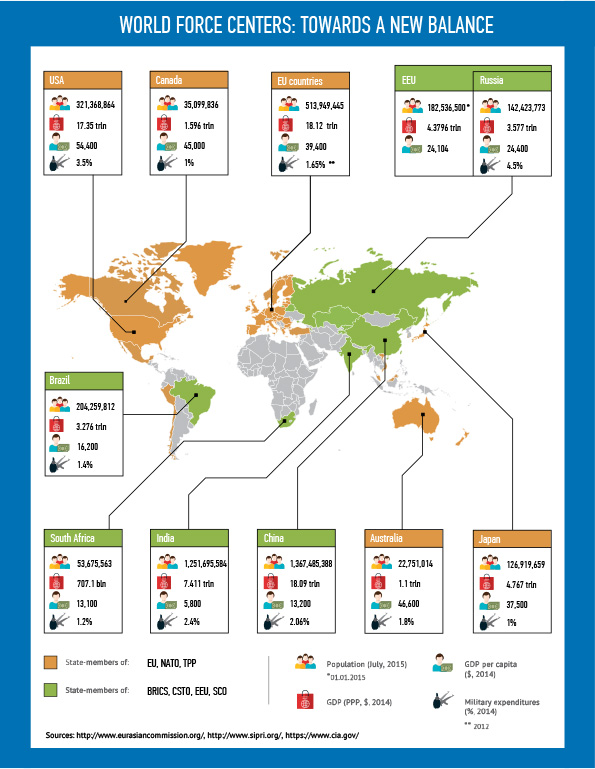

The world stands at a parting of the ways: will the growth of internal problems in the leading countries and the rise of non-western centres of power bring us to a revolutionary explosion or will change be slow and systematic? For the moment the West is still in the lead. But there are two trends undermining this status quo: the relative decline of America’s allies, from the EC to Japan, and narrowing of the gap between them and BRICS countries in terms of influence on global processes.

The Western community is increasingly impatient at the actions of large non-western states, aspiring to go their own way on global issues. This impatience is manifested even when the non-western countries try simply to assert their interests in the immediate proximity of their own borders, something that was previously regarded as the evident right of any serious power. So, as regards security, the main source of friction is the periphery of emerging states. The West is concerned by the situation in the post-Soviet space and in the South China Sea and issues informal guarantees to the small neighbours of Russia and China. Moscow and Beijing understand these actions as an attempt to stifle their aspirations.

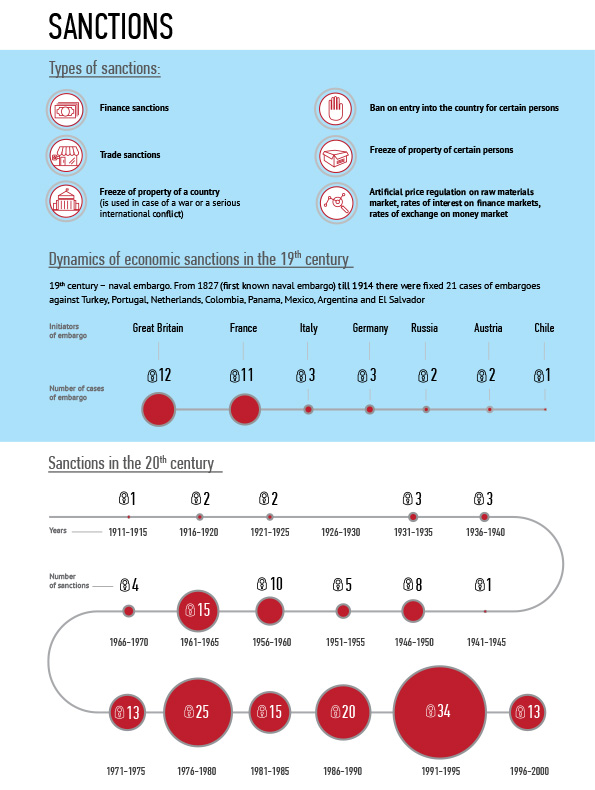

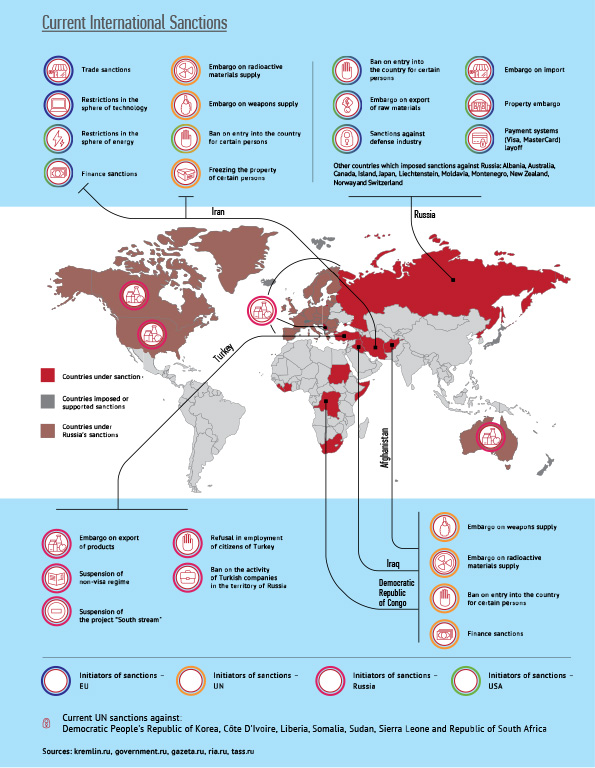

A revolutionary demolition of the western-centric global order is not inevitable. There is still scope for orderly reform. This refers not only to mutual nuclear deterrence between Russia and the West, which renders war unlikely. The BRICS countries have already learnt to make the existing global system work to their own advantage. But more extensive use of sanctions as a political tool has led many to wonder whether interdependence is turning into a source of pressure and vulnerability. This undermines the foundations of the global economic system. It also hinders initiatives to create trade and economic mega-blocks, which can create new, non-universal international rules.

Discord between the core of the global system and emerging states is assuming an epistemological character. The parties find it increasingly difficult to agree on the definition of such concepts as “stability”, “security”, “progress” or “democracy”. The West relies on a holistic conception of global development and the values that are to be promoted, but the outcome of its efforts is often the contrary of what is intended. Non-western countries know what they oppose, but they have not yet found a single, integrated vision of how the whole system should be structured. Although they are striving to construct such a vision. In the global arena there is increasing divergence between the concepts of freedom and justice: the first is held aloft by the western community, while the second is the slogan of the rising non-western states.

During the Ukrainian crisis of 2014–2015 the issue of military security in Europe returned to the agenda for the first time in 25 years. Russia and the West flexed their muscles and the prospect of an armed confrontation no longer belonged to the realm of fantasy: the risk of a major war in Europe, which seemed to have been left behind once and for all in the 20th century, was back in focus. The situation has been further complicated by the latest phase of the Syrian conflict. For the first time, Russia and the United States and its allies are carrying out large-scale military operations in the same region. And although the American and Russian militaries have apparently agreed on the minimisation of risks, the dangers inherent to this situation were demonstrated by the acrimony between Russia and Turkey, which erupted after Turkey shot down a Russian military aircraft.

Finding themselves on the edge of a precipice, Russia and the West asked themselves: what are to be the rules of this “great game” and will there be any rules? For the moment the different sides are giving different answers.

The crisis can be overcome if its cause – mutual distrust between Russia and the West – will be dealt with. The experience gained in the period since the Cold War shows that trust cannot be based on an ideological “unconditional surrender”, the acceptance by one side of the opinions and perceptions of the other. The defects of such an approach are obvious even within the European Union, where a “mental unification” is still lacking, so its attainment in relations with Russia is not to be dreamt of.

The use of force and its limits

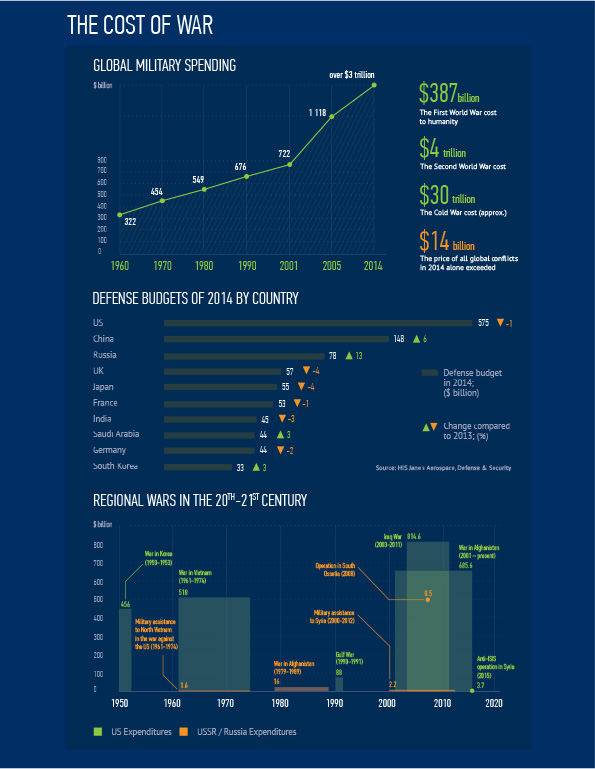

International relations in recent years have repeatedly cast doubt on the efficacy of military force and the ability to achieve political objectives by armed methods. The decision to use force has frequently been based on an incorrect calculation or on ideological arguments (in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria), which had nothing to do with the real national interests of those involved.

War that does not aim to achieve territorial occupation is a new phenomenon in international relations. We have seen wars unleashed under the banner of “human rights”, justified by the need for “humanitarian intervention” and a “responsibility to afford protection”. Revolutionary military technology has changed the nature of war. The use of precision weapons, unmanned aerial vehicles, hybrid tactics and strikes against information infrastructure and satellites are now the most probable scenarios for a military conflict between the great powers. The development of rules of the game in these spheres is a matter of common interest and urgency.

Mutual nuclear deterrence remains an effective tool. Discussion of the use of nuclear arsenals in military operations has re-emerged for the first time in many decades in the context of the Ukrainian and Middle East crises. But the chief novelty of the 21st century is non-military methods of suppressing an opponent through political, economic and technological isolation. The questions arise: what is the potential and implications of such a deterrence policy for the global development? Do sanctions resolve existing problems or do they only defer their solution, and even lead to an escalation of conflicts? The interdependence, which was supposed to favour compromise, produces a quite different effect: it becomes an opportunity to cause the largest possible damage to the other side by smashing the newly created bonds, often without regard to the costs for the first side.

International policy today is universal and total. Decisions to use force are increasingly taken in the interests of specific groups. Public pressure on government, domestic political needs and militarisation of civil society impact the external and military policy of countries. Non-state actors-terrorist and rebel movements or individual fanatics – have emerged as key participants of conflicts. They are no match for the concerted force of states, but the scale of the damage, which they can inflict, is disproportionate.

The world of ideas

The session of the Valdai Discussion Club in October 2014 posed an evident question in the contemporary context: “New rules or no rules”? A year later we seem to have movement in the direction of new rules, or at least their framework in the form of a bipolar structure of the world. Although the term “bipolar”, with its Cold War echoes, is perhaps undesirable and it would be more accurate to speak of two groups of powers following different vectors of development.

The West has manifested strong hostility to the long-term paradigm of a harnessing of Russian and Chinese interests in continental Eurasia. There was a symbolical expression of this when Western leaders refused unanimously to attend military parades celebrating the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, not only in Moscow (explainable in terms of the Ukrainian conflict), but also in Beijing (which has no part in that conflict).

The trend towards a new division into camps is not purely a consequence of the Ukrainian crisis and the conflict between Russia and the West, though these factors have acted as an accelerator. Dissatisfaction with the western mainstream and the world order that it dictates intensified from the beginning of the century, and reached a new level after the crisis of 2008–2009. The formalisation and gradual consolidation of the BRICS, on the one hand, and the dramatic electoral rise of radical protest parties or individual politicians with extreme platforms in Europe and the USA, on the other hand, underlined the growing instability of the mainstream. The next stage is global political legalisation of alternative development models, both inside and outside the West. Estrangement between ordinary people and the political elite is increasingly manifest, even to a point where the radical, inhumane ideas of DAISH achieve popularity among certain groups not only in the Middle East, but also in Europe and Eurasia.

The growing importance of alternative projects entails a revival of the role of ideologies and ideological struggle. For a quarter of a century after the Cold War ideological messages were a monopoly of the West, while others either accepted them or locked themselves away in a combination of fortress mentality and “Realpolitik”. Now, though, attempts to formulate an ideological response to the West are apparent. All the more so because the new type of confrontation has less to do with military factors and more to do with world view and communication. The coming decade may well see an ideological renaissance.

The urge of the West to replace ideologies in their traditional understanding by standardised “common” values is driving demand for alternatives. There is a disillusion with an imposed model that presents itself as universal. Particularly since its efficacy is open to doubt. The inability of economies, even in developed countries, to afford the level of social guarantees and resource reallocation that was taken for granted just a few years ago is promoting dissatisfaction and reviving the issue of social justice, which had seemed forgotten in Europe. The issue tends to assume a xenophobic aspect in the context of the migrants inflow.

Simultaneously, gradual crystallisation of the BRICS is working to change the situation. The political course taking shape within the BRICS framework is perceived not only as a continuation of the ideology of developmentalism, but as the assertion of a comprehensive global project.

Тhat is not to suggest, however, that ideological consolidation between non-western countries will ever achieve the western level. The Atlantic community is a unique example of value unification. By contrast, non-western states are together in stressing the importance of diversity, insisting that no uniform emblems of a “modern state and society” are either desirable or possible. This is an approach more in tune with the conditions of a multipolar world.

While the ideological opposition still remains vague, pressing cultural and (increasingly often) religious contradictions are already in evidence. The situation worsened significantly in 2014–2015 with the appearance of a principally new factor in global policy: DAISH. The so called “Islamic State” challenges existing civilisation as such, defying moral and political standards. Though the global nature of the threat posed by DAISH is generally recognised, the proposed strategies for combatting it vary greatly.

Barack Obama has openly equated the threat posed by Russia and by DAISH. Such an approach, though occasionally played down out of tactical considerations, suggests that the threat posed by Islamic radicalism and terrorism will not only fail to re-establish the previous rules of the game, based on a “quasi-consensus”, but will escalate the division into centres of power and the crystallisation of bipolarity. And such tragic events as the November terrorist acts in Paris (bound, unfortunately, to be repeated in various parts of the world) will only promote cooperation for a short time or for the solution of specific tasks.

Another globalisation

A single universal international order with shared values and development models is unattainable in the increasingly fragmented and pluralist international system. However, in the context of global interdependence and interfusion, a “war without rules” and “war of all against all” will lead to catastrophe. The first symptoms are already evident: a series of upsets in the global economy (including the energy and financial sectors), the migration crisis in the EU, the spread of DAISH and low efficiency of efforts of global society to oppose it, climate change, etc.

The world order like the modern state suffers from an imbalance between two major principles – justice and efficiency. The harmonious combination of these two principles based on international institutions, which was sought by many people, has proved ineffective due to failure of the institutions to correspond to a changing reality. A strict hierarchy has also failed to ensure efficiency. And a simple balance of power, as used to exist, is impossible due to the complex and non-linear nature of global processes and the large number of players involved in them.

The gradual transfer of economic cooperation and integration to the regional level does not call time on globalisation. The key to success of most regional communities is their integration into the global economy. Global and regional institutions and trade regimes must strengthen and not weaken each other. In order to create a balance, rules are needed that will allow groups of countries to efficiently manage global interdependence, to coordinate measures for counteracting transnational challenges and threats.

Globalisation goes hand in hand with better and closer relations, including a process of integration, at the regional, bilateral and “mini-lateral” (i.e. with a relative small number of participants) levels. More competition, redistribution of power in the world and general vulnerability in the changing international context makes key players transfer their efforts to the bilateral and regional level in order to create a favourable environment in their immediate vicinity (since it cannot be attained at the global level). Regional communities are coming into existence to promote the development and security of the countries that are included in them and particularly of the leading members of these regional communities.

Regional economic groups are being transformed into larger transcontinental or transoceanic groups, since “narrow” regional units find themselves unable to maintain competitiveness in the context of more intense global competition. The new “large” communities are not integrational in nature, but offer more intense trade regimes and general rules of cooperation in trade and the economy. The smaller integration associations are not dissolved in such communities, but rather “woven” into them through matching of models and interests.

Towards a new balance

The escalation of chaos and uncontrollability in international relations cannot last forever. As described above, we are probably witnessing the start of the formation of a new world order based on a factual, though not institutionalised, balance of two major groups of states. These two groups are not doomed to confrontation. They will maintain close relations at the economic and human level, seek a common response to development problems and challenges, and sometimes join hands to resist threats, mainly those of an anti-systemic nature. All of this is perfectly compatible with the existence of permanent competition between the two groups.

Such competition is natural in view of insurmountable cultural and value differences, as well as objective contradictions between development objectives. The current stage of relations between Russia and the West may prove a step on the way to a “normalisation”, which adequately reflects the competitive nature of their interests, and to the rejection of a pretended “strategic partnership” (perhaps sincere and not consciously grasped) that has not worked.

Geographically these two groups will include the USA, the European Union and their allies, on the one part, and China, Russia and a number of other countries supporting them, on the other. Their economic base will be two ocean partnerships – Atlantic and Pacific – and a “harnessing” of integration and trade and investment projects in Greater Eurasia. The communities are already on their way to such relative consolidation.

However, while the internal structure of the “Western” group of countries is already formed and is unlikely to change significantly, the “East- Eurasian” association of Russia and China is still in the process of intensive formation, primarily through systematisation of the activities of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

It would be mistaken to expect legitimisation of the future model of the world order by the decisions of a congress or international institution. Everything was much simpler 200 years ago: war had served as a universal measure of the international hierarchy, and diplomacy was the means of its formalisation. Congresses are possible when there is a clear distribution of power and roles between the participants, when there are clear winners (whether wise, as in 1815, or short-sighted as in 1919 or 1991) and losers. Today a new order is not being built directly on the ruins of war, but is gradually taking shape out of the dialectical chaos of competition and interdependence.

This future order cannot be based on winners and losers. The winners of the Cold War will not negotiate on equal terms with those who are dissatisfied with its outcome. The West will never recognise the equality – moral, ideological or political – of other players. It will resist institutionalisation of the new international structure. The sensations experienced at the end of the 20th century were too sweet: undisputed power, combined with absolute moral and political correctness. But a return to the glorious 1990s is also impossible for the West. International relations in the “grey area” that comprises most of the countries of Latin America, Africa, Southern and South-Eastern Asia, and perhaps Eastern Europe, will remain a challenge to international security.

The new global balance of power will be unlike the Cold War system. That system was unique and unrepeatable in human history, being characterised not so much by an ideological opposition between two camps, as by a complete lack of interconnection and interdependence between two parts of the world – their physical split. World civilisation had never experienced anything comparable and will not experience it again in the future.

The new framework will most probably keep the free flow of people, goods and capital. If efforts to create new international financial institutions and integration associations prove successful, that will be greatly to the benefit of global controllability. Governments and private companies will have a choice, which will stimulate competition between institutions and increase their vitality. In some sense the future system will be an antipode of that, which existed during the Cold War, and also of that, which failed to come about at the end of the Cold War. It will be characterised by maximum flexibility and variability, necessitated by the impossibility of establishing hard and fast rules.

Both groups will pursue a periodic “hybrid”, more or less intensive struggle with each other. The global “great game” will be played out both in the geographical spaces of the “grey area”, and in the globalised spheres of information, technology and others. But the hacker attacks that the major powers already use against one another, as well as information campaigns and diplomatic intrigues will not terminate economic and human links. The possible transfer of territories, which may become inevitable in the context of numerous territorial disputes and dilution of the solid international legal base, will also be less than catastrophic. In some cases de-facto transfer or withdrawal of territories will be compensated by the preservation of economic openness.

Sanctions and countersanctions, both explicit and implicit, will be usual practice. As universal rules of global trade become moribund (the WTO is an increasingly ceremonial body), mutual restrictions will be standard in relations between major economic and investment blocks. Global nuclear deterrence will also limit the scale of disagreements, preventing their escalation into military conflicts. Diplomatic work to control the escalation of inevitable conflicts will be a vital task of international consultative structures, such as the United Nations Security Council. Informal platforms, such as the G20 can be viewed as an analogue of the UN Security Council for the economy. And, since the legitimacy of the UN Security Council is likely to be called into question due to its limited representation, the remit of the G20 may actually extend to political issues. Particularly since it is becoming impossible to separate economics from politics and, when political and economic expediency collide, the first are increasingly given priority.

Relationships within each group will probably be far less hierarchical than might be expected from the experience of the Cold War. Decisions and policies can only be formulated through consensus and not through diktat. Despite its economic and military power, it is not in the interests of the USA to impose its will by force. As can be seen from a comparison of the events of 2003 and 2014–2015, it is easier and more efficient to implement a compromise solution than a solution by force. The model of mutually beneficial compromise is even more natural on the Moscow-Beijing axis, where the economic power of the People’s Republic of China is an excellent match for Russia’s military power.

It is also important that the countries within each group are free of objective, deep and antagonistic contradictions in respect of one another. The development needs of the individual states are not such as to give rise to such contradictions.

Russia’s national development objectives in Central Asia need not conflict with those of China, and vice versa. Both of the major powers are seeking resources and opportunities in their common neighbourhood: Russia is particularly interested in recruiting workers and China is in search of investment expansion. Both Russia and China are deeply committed to regional security and the stability of political regimes. The more China invests in the “Silk Route” area, the more pressing it will become to ensure the security of that zone, and the only guarantor of that security (for example, in Central Asia) is Russia.

Europe is not a competitor for the USA, but rather its closest ally in terms of shared values and economic importance. Both the USA and EU are interested in the deterrence of other power centres and retaining monopoly opportunities in Africa, Latin America and, to some extent, Asia.

It may be a simplification to equate the West – non-West dichotomy with the balance of power worldwide, since the cultural and ideological separation and the entire international system is likely to be dynamic. Rather, the point is that the aspiration of the rich West to preserve and strengthen its leading position in the international system is bound to stimulate others to aspire to a similar position.

We should stress that we are still at the very beginning of the formation of such a system. Its creation will be a long process. Breakdowns and backward steps are bound to happen, as well as periods of temporary rapprochement to oppose common threats, such as that posed by DAISH. But international and political escalations will gradually become a matter of course and will no longer be perceived as harbingers of Armageddon, as happened in wars throughout history until 1945. In a more distant perspective the new balance will create the conditions for tougher global unity, based on recognition by both groups that neither can dominate. Such rapprochement will be assisted by the escalation of anti-systemic threats from forces that aim to destroy any standards and rules (DAISH is again the prototype).

That is why the new bipolar world order that we have described seems the most likely, natural and, consequently, the most desirable. It will be a “path of peace”, not without imperfections, but stable and without extremes.

* * *

Leo Tolstoy believed that global history is “the history of all the people who participate in its events”. This is truer today than ever. Transparency of borders, availability of technologies, the universal expansion of democracy as a form of social organisation, and the total domination of communications means that everyone has an impact on the historical process. This makes the process less predictable, but that is no excuse for relying on a benign fate – the stakes are simply too high.

Tolstoy wrote: “For history there is no irresolvable mystery in the union of two opposites – freedom and necessity, – the mystery that is found in religion, ethics and philosophy. History assumes a concept of human life, in which these two opposites have already been united.” This Tolstoyan view is highly relevant today, when the hopelessness of efforts to force events into a dogmatic framework is abundantly clear. The role of leaders, states and communities is to understand the limits of the possible and boundaries of the permissible, and to create a system of relations with minimum risks within this framework.

Authors

The report was prepared by the research team of the Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club

Oleg Barabanov

Timofey Bordachev

Fyodor Lukyanov

Andrey Sushentsov

Dmitry Suslov

Ivan Timofeev

Executive Editor Fyodor Lukyanov

Academic Director of the Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club

The initial draft was discussed at the 12th Annual Meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club in Sochi on October 2015 and finalised upon the results of the discussion.

Chairman of the Board of the Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club Andrey Bystritskiy