Stability is invariably present among Russians’ most precious values. According to the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM)’s 2013 findings, stability is above law, democracy, human rights, dignity, conscience, spirituality, and even success. Its significance has since gone up from 21% to 27%.

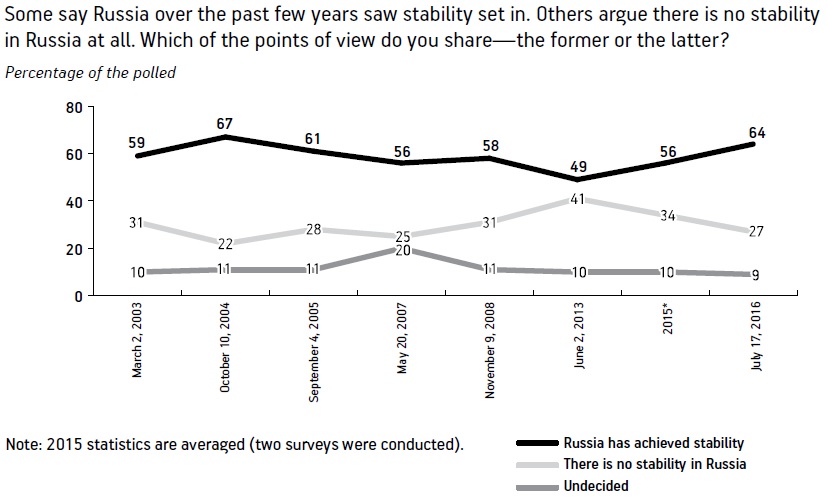

However, the very same FOM says that according to its surveys conducted since 2003 most Russians agree there is no stability in Russia (with statistics ranging from 49% in pre-crisis 2013 to 64% in difficult 2004). Stability is a feeling shared by 22% to 41% of those polled (Fig. 1). The situation in 2013 was relatively favorable: nays and ayes were split almost evenly (49% vs 41%). The summer of 2016 saw a slump almost to the negative point of 2004: 64% felt a lack of stability.

It should be remembered the country saw far worse periods in its history. In 1994, only 4% (!) of Russians thought the country had achieved stability.

What is stability to ordinary respondents? FOM surveys of ten years ago say that Russians most often rate stability from the economic and social point of view, and not the political one. Here are the most typical replies by respondents to FOM polls: real wages paid on time, pensions for retirees, higher salaries and pensions, people’s well-being, high living standards, life without inflation, no price hikes, steady production growth, support for youth and the aged, roof overhead, real opportunity to get education in a government-financed university, availability of medical services. Quite often stability is associated with such words as “confidence,” “consistency,” “well-being,” “certainty,” “guarantees,” and “predictability”—all having clear economic connotations. Whenever they mention stability, it is their own future that people have in mind, a future that can be calculated, predicted and planned (“I know what there will be tomorrow”).

Fig. 1. Stability assessment monitoring in Russia (FOM, 2016)

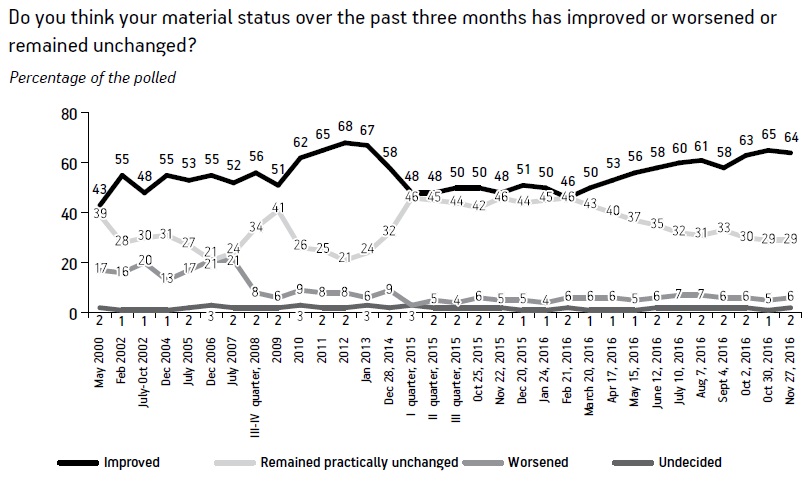

These days, sociologists point to alarming trends (only FOM findings are cited here, but they are consonant by and large with VTsIOM and Levada Center polls). Most respondents (77%) say that an economic crisis in the country is a hard fact. Slightly less than half (42%) believe that the economic situation is bad (another 45% are more reserved—their diagnosis is that the situation is “satisfactory”). Lastly, nearly one-third of Russians say their material position has worsened over the past two or three months (Fig. 2). The geopolitical situation is a reason for alarm, too. Half of Russians (52%) see a real threat of large-scale war between Russia and NATO countries, while a little less than 43% believe that its probability is higher than in the 1970s.

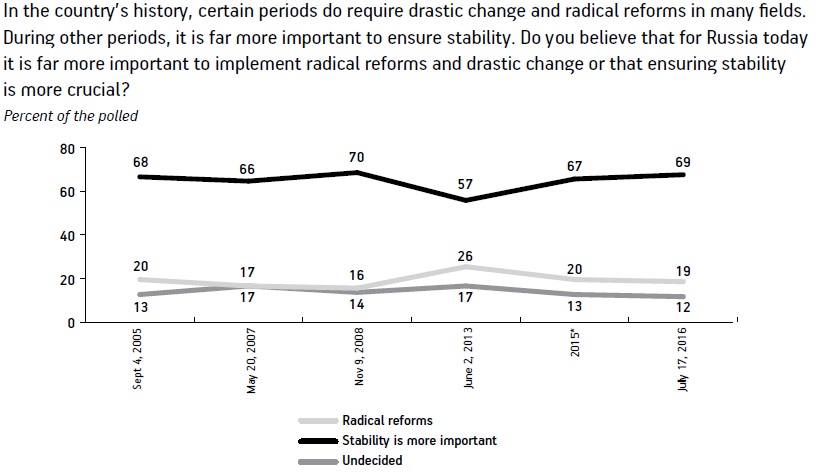

It is only natural that in the current situation demand for preserving stability is large (Fig. 3). In the pre-crisis year 2013, 57% of Russians believed that stability is more important than radical reforms. As many as 69% say so today. It is noteworthy that stabilization expectations are characteristic of not just low income social groups, where such sentiment has been traditionally strong. Business people, senior managers, people with far higher incomes are critical of the situation in the economy and call for stability.

Fig. 2. Material status assessment monitoring in Russia (FOM, 2016)

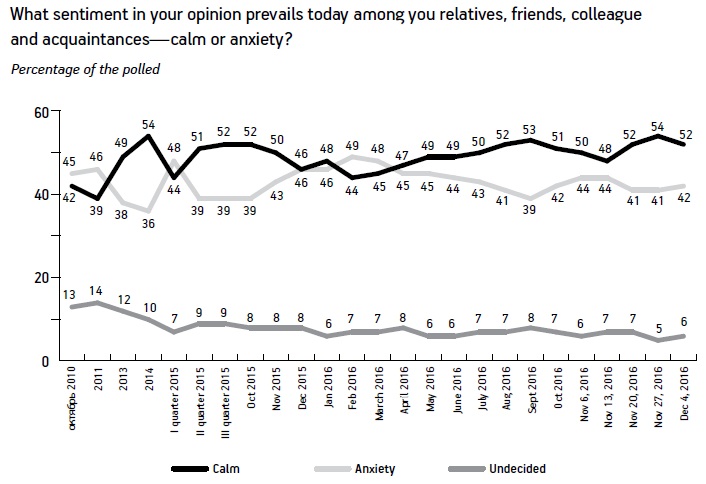

But it would be wrong to say that negative attitudes prevail. Calm and alarm are roughly in balance (Fig. 4). For some people instability is a customary environment to which they have long got accustomed psychologically (half of those who remain calm believe that there is no stability in Russia).

Researchers regard stability as Russians’ basic value and the kernel of Russia’s modern conservative ideology. But the idea of stability has undergone complex evolution over the past decade, not to mention the great variety of everyday routine interpretations of this term. Ten years ago, participants in surveys conducted by the author of this article presented their associations the word “stability” evoked. They shared their fantasies, drew cartoons and took other color and projective tests. The gist of those findings looks as follows.

Fig. 3. Survey of stability ratings in Russia (FOM, 2016)

Fig. 4. Monitoring of sentiments (FOM, December 2016)

The perception of stability is a combination of primary sensuous distinctions: the feelings of balance and stability of the body, stability of the world around and multifaceted shades of emotion. These basic feelings are constantly reproduced in drawings, associations, demotivators, advertisements and phrases like “to stand firmly on one’s own feet” and “not to go to extremes.”

Fig. 5. Sensuous experience of steadiness / stability as represented in drawings by respondents

The understanding of stability is temporal: we single out continuity and changes of events, “sameness” and movement. Stability is more often described as recurrence of events of the past, present and future (“That’s the way it was yesterday, is today and will be tomorrow).

Stability is an emotionally positive phenomenon by and large, although some negative comments do exist. Stability is more often than not associated with good (the share of positive comments is 60%-75%). Stability is associated with “positive” colors (blue, green, and yellow) and semantic proximity to the concepts of “confidence,” “order,” “well-being,” and “wealth.”

The understanding of stability is archetypal and metaphorical, because it is tightly linked with the primary distinctions of the object, time, good and evil. The abstract meaning of stability is connected with the meaning of clearer phenomena that are emotionally far easier to perceive—a house, a stone, a cube, a circle, an anchor, a marsh, death, and so on.

Stability is not just a means to draw the contours of a stable society as a social construct that represents not the world as such but a collective ideal of reality. Stability at the basic level is always a dream.

The everyday understanding of stability is always relative and closely pegged to the social context. Inclusion in specific social positions and practices considerably modifies the semantic matrix of stability. Different social groups have their own shades of stability. The understanding of stability may have gender, age, professional and political distinctions.

The above describes the phenomenology of stability—the level of perception, primary senses, and personal evaluations. In the broader social context, the notion of ‘stability’ has a very complex history and a wide range of interpretations. One can identify several stages the understanding of stability has gone through in Russia.

DISCOVERY OF STABILITY. UP TO THE 1990s

When did the concept of ‘stability’ come into everyday use? No detailed research into the history of the word “stability” is available at this point. It is the language experts’ job to find out when exactly the word was imported and firmly established itself in the Russian language. At this point, a couple of brief remarks on this score. In all likelihood, the world “stability” began to be widely used in Russia at the end of the 19th century. For instance, in Nikolai Karamzin’s History of the Russian State and Sergei Solovyov’s History of Russia from the Earliest Times, the word “stability” and its derivatives are not mentioned even once. The same is true of works by Vissarion Belinsky. The word “stability” is absent from Vladimir Dahl’s dictionary and the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary.

One may surmise that the concept of ‘stability’ that is universally accepted in modern social sciences is not deeply rooted in Russian culture (in contrast to such concepts as ‘order,’ ‘truth,’ ‘good,’ ‘justice,’ or ‘peace’).

At the end of the 19th century and in the early 20th century the Russian language absorbed many foreign words pertaining to the realm of politics and science. Certainly, the word “stability” does not belong with the kernel of socio-political vocabulary, in contrast to such words as “Socialism,” “Communism,” “nihilism,” “liberalism,” etc. At the beginning of the 20th century it is already widely used in political pamphlets and essays.

G. Lelevich in his article Roads and Crossroads (Stabilizationist Trend in Literature), published in 1927, often resorts to such phrases as “stabilizationist mentality” and “stabilizationist sentiment.” The author is very critical of the risks he sees in stabilizationist sentiment that manifested itself in literature and journalism after the end of the Civil War (“striving for satiety,” “capitulationism” and “moral leprosy”).

Analysis of historical and sociological facts indicates that the word “stability” was noticeably present in the vocabulary of natural sciences and in the political and everyday discourse of the 1970s and 1980s. For instance, the Institute of Sociology in 1979-1980 conducted an expert poll entitled “Do You Expect Change?” to collect a colossal amount of remarkable facts and ideas. The theme of stability/sustainability of the Soviet system was central to the poll. The general tonality of experts’ replies revealed the feeling of the system’s inconsistency and of its growing internal rifts. Experts extensively employed terms like ‘steadiness,’ ‘stability,’ ‘inertia,’ ‘stagnation,’ ‘stable crisis,’ ‘self-preservation,’ ‘improvement-worsening,’ and ‘dead end.’

The feeling that in the 1970s-1980s Soviet society had reached a dead end and was degrading might serve as a reason to regard stability as a negative phenomenon: it was perceived as a stagnant bog or as a graveyard. As liberal poet Bulat Okudzhava wrote in the early 1980s: “The Roman Empire in the days of decay produced an impression it was strong and OK…”

Soaring fears of the arms race and terrorists’ activity were another reason for putting the focus on stability. Man-made disasters, frequently reported by the mass media, contributed tangibly to filling stability with specific content.

In modern society, the general trends in the state of public mind largely depend on television rhetoric. Consequently, it is essential to take a look at the most frequent uses of the word “stability” in the mass media in the 1970s and the 1980s. First and foremost, there were phrases and word combinations describing the growing arms race and the Middle East: “strategic stability,” “foreign policy stability,” “international stability,” “financial stability,” “oil market stability,” etc. It is noteworthy that Russian sociologist Boris Dubin back in 2004 said one should not think the modern “stability” rhetoric is original.

Stability could be unmistakably identified in the proclaimed values of the Soviet citizen. Vladimir Sokolov, Senior Research Fellow at Higher School of Economics, found out that young people put the value of a calm life and stability of the achieved position in society and at work in 8th place after the family (1), interesting job (2), other people’s respect (3), awareness of being useful to other people (4), material wealth (5), opportunities for indulging in activities of interest (6), and chances to broaden one’s outlook (7). Polls were conducted in 1972-1973 and surveyed an audience of 1,000 young men and women aged 17-25. The Soviet person put a strong emphasis on such values as peace, strong state, and order.

Perestroika pushed the idea of stability to the sidelines and marked it as stagnation. Ideas of change, acceleration, movement, reform, new political thinking, transformation, freedom and democracy came to the fore. However, the image of stability staged a prompt comeback and its reincarnations took far more complex, controversial and sometimes radical shape.

TOWARDS ENDING CHAOS AND ACHIEVING STABILITY

The first forerunners of modern stability rhetoric appeared in 1990 or even earlier. The theme of stability mostly came second after the statement of instability. While studying this theme in Russian sociology one can come across quite a few remarkable illustrations, for instance, an excellent article by Rozalina Ryvkina and Leonid Kosals entitled The Mechanism of Destabilization. What and Who Makes Our Society Unstable (1990).

Who was the first to come out with the political slogan of stability and when that happened is anyone’s guess. Someday historians may provide an answer. Boris Yeltsin’s well-remembered inauguration speech of July 10, 1991, “Great Russia Is Rising from Its Knees,” contains not a single hint at stability (freedom, justice, reforms, well-being, peace, prosperity, democracy, property, popular support). The State Committee on the State of Emergency in August 1991 made the first attempts to lend stability an ideological aspect. It was under the slogans of establishing economic stability, preventing famine and declaring a war on crime that the Committee attempted to change the political course.

Yuri Levada dated the stability slogan to 1993-1994. It should also be remembered that the ideologeme “For Stability and Development, Democracy and Patriotism, Confidence and Order” was officially proclaimed in 1995 by the socio-political movement Our Home Is Russia (an abortive project to create a ruling party). A group of legislators calling itself Stability emerged a short while later. It was in 1995 that the author of this article was asked to write a dissertation on a very topical subject: “The Problem of Stability of Social Systems.”

Analysis of sociological surveys of those days identifies growing disillusionment with reforms and greater popularity of stability as a fundamental idea.

1996. Stability was the argument for making the choice in favor of Yeltsin, Zyuganov and Lebed.

1997. 66% of Russians hailed the slogan “Enforce compliance with laws, restore order and guarantee stable and normal life.”

1998. On the list of individual values, material wealth and good housing are at the top (76%), good everyday conditions come second (61%), and stability of life and no turmoil, third (33%).

It goes without saying that the default of 1998 was a powerful impetus to the political and everyday routine ideology of stability. “Restore stability,” “provide stability,” “achieve and strengthen stability” were the watchwords of the day. A short while later stability became part of Yevgeny Primakov’s political image. Such associative chains as Primakov–Stability and Primakov–a Stable Economy Based on Development Dynamics instantly turned into a brand, which, however, made a clear allusion to images of the past. In his interview of November 24, 1999, Primakov addressed the electorate with a reminder that “according to a recent opinion poll Russians named Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov as the two best Soviet leaders who symbolized stability and order.” It should be remarked that FOM pollsters found experts certain it was Primakov’s efforts that made political stability in the government and society possible.

Bomb blasts in Russia in 1999 became a powerful catalyst of stability rhetoric. The Yedinstvo (Unity) party and Vladimir Putin emerged on the political scene with pro-stability slogans. At the end of 2000 the Russian president said that “2000 was a year of Russia’s stability and unity.”

STABILITY REGAINED BUT DOUBTS LINGER. THE 2000s

The stability rhetoric of the 2000s is multifaceted. The political discourse, just as everyday mentality, presents stability in a variety of ways. The range of political opinions is so wide that one cannot but have the feeling the “signifier-signified” link is disrupted (the idea of stability vs real stability/instability). French philosopher Roland Barthes described this process as mythologization of consciousness.

Stability is painstakingly interpreted, imagined, camouflaged and simulated depending on the political aims and the ideological code. Here are some brief semantic emphases found in statements by political leaders in 2004-2007.

United Russia. Stability is a goal. Stability is a value. Stability is top priority. Stability is a reality (in the second half of the 2000s the leaders will begin to mention decent living standards, development and innovations as goals worth seeking).

Communist Party of Russia. Stability is fictitious. It is a myth and an illusion. Stability is an alien value.

Right-of-center opposition. Risk of such stability. Pseudo-stability. Neo-stagnation. Development as a benchmark.

National Bolshevism. What stability can a revolutionary aspire? Stability is a philistine’s value. Stability our way.

Liberal Democratic Party of Russia. Stability is above all. It spells order, justice and security for Russians.

In official use the word “stability” is ever more actively transformed into a legitimate semantic unit denoting a condition for establishing and justifying social order. Sociologists describe this term as legitimation. The legitimation of stability as “top priority” implies an opportunity to “explain” this phenomenon, which lends it a regulatory status and makes it recognized and supported by most actors. The same happens not just in the political space, but in the advertising campaigns of major brands and in social advertising.

And still, discussions along several clearly distinguished lines go on alongside the active legitimation of stability.

Does the country have stability, or an “imitation of stability”, or an “illusion of stability”?

If there is stability in reality, what is the nature of that stability? Stability or stagnation?

What is the relationship between stability and development?

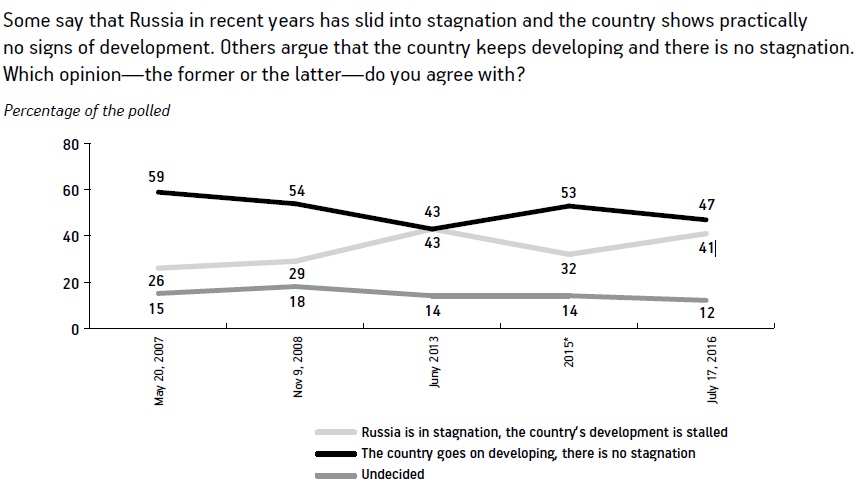

Fig. 9. Survey of stability-stagnation comments (FOM)

The public opinion is deeply split over the situation in today’s Russia. The discussion is gaining steam, with a great variety of opinions, expectations and ideas being voiced. A quarter of those polled by FOM in 2007 (26%) said “Russia is in stagnation; the country shows practically no signs of development”. The share of such replies kept growing. In 2013 as many as 43% of Russians described the situation in the country as stagnation (Fig. 9). Regrettably, the period of 2011-2012—the time of Bolotnaya Square demonstrations and growing protest—is absent from the chart. The surveys of those years identified demand for change and renewal, in particular, from the groups that act as the driving forces (the middle class, professionals, and the youth).

Sociological and psycho-semantic studies found that the notions of ‘stability’ and ‘stagnation’ differ in everyday use, with “stagnation” perceived as a rather negative phenomenon. The notions of ‘stability’ and ‘development’ are not contrasted but, on the contrary, considered as inter-related ones.

Criticism of stability is manifested most clearly in Internet demotivators. The main themes of this online creativity are:

- This is not stability

- This is stability

- Stabilization of poverty

- This stability is authoritarian

NEW COURSE: TOWARDS STABILITY AS A RESPONSE TO THE CRISIS, 2015-2016

Two dramatic years—2014 and 2015—propelled stability into the group of crucial everyday benchmarks. This sentiment is seen not only in the invigorated demand for stability and fears of war and of likely turmoil, but in the high political ratings, the approval of foreign policy, patriotic feelings, negative attitude to the West and a low level of protest. State Duma election returns are a major sign of stabilization mentality. President Vladimir Putin pointed to this at a meeting with Cabinet members on September 19, 2016. “Amid these difficulties and a large number of uncertainties and risks the people unequivocally choose stability and trust in the leading political force. They trust the government, which relies on the United Russia party in parliament, they are certain that we will be acting professionally and in the interests of the country’s citizens.”

Table 1. Russians’ benchmark values (VTsIOM opinion poll,August 15, 2016)

| Our country needs stability, this is more important than reforms and related changes | 63% | Our country needs changes, new reforms, even if these changes are fraught with risks of losing stability | 30% |

| Russia’s policy must be geared to enhancing sovereignty and developing its own Russian civilization | 72% | Russia’s policy must be aimed at concluding an alliance with the leading Western countries and entering the modern Western civilization | 20% |

| Russia must be a great power with strong armed forces and influence all political processes in the world | 58% | Russia should not try to strengthen its great power status, it is better to ensure the well-being of its own citizens | 33% |

| Russia needs a “firm hand” that will restore order to the country | 66% | Political freedoms and democracy are something that should not be abandoned under any circumstances | 25% |

| I may find suitable the phrase: For this person, it is very important to live in safety, he does his utmost to steer clear of everything that might pose risks. It is important for him to follow traditions and customs adopted in his family or his religion, it is always important to behave himself and not commit something that other people may disapprove of | 58% | I may find suitable the phrase: For this person, it is important to propose new ideas, to be a creative personality, to follow one’s own way. It is important for him to have adventures and take risks, he seeks a life full of thrilling events | 35% |

The stability rhetoric has developed some new traits, because the current events are fundamentally different from the events of 2008, the early 2000s or the 1990s. Mobilization around the political leader is the new meaning. The urge to brace up is the key message (“We’ve been through this many times in the past! We’ll manage!” We shall overcome!”). The active groups, such as businessmen and senior managers, come out in favor of new solutions and new strategies. All this does not rule out the possibility of local protests the sociologists find hard to predict.

In conclusion, let me cite VTsIOM statistics from a press release under a brisk title Password of the Day: Security. Stability. Sovereignty. Sixty-three percent agreed with the following statement: “Our country needs stability. This is more important than reforms and related change,” while only 30% believe that “our country needs changes and reforms, even if reforms involve the risk of losing stability.”

Alongside pro-stability statements, the participants in the VTsIOM poll declared their wish to have security and follow the traditions and customs, the importance of sovereignty, great power status and a firm hand. There is a very heuristic set of statements, showing the range of values and the correlation of the idea of stability with other concepts.

* * *

The idea of stability has been through a complex process of semantic transformation—from an abstract foreign borrowing, a scientific and political term to a crucial slogan and ideological belief. Even though the idea has been revitalized today, a renaissance of the ideology of stability is unlikely to follow. Stability is a primary need and a fundamental value. It easily matches other concepts and evokes a response from very different people. But the idea of stability is an elementary one. It is a life vest in a world of social chaos. U.S. science fiction author Alfred Bester in his novel The Push of a Finger described a society of 2909 where the basic principle of existence is stability. As Bester shows, the idea of social stability may have the same plight as many other socio-utopian projects. The wish to make stability the paramount value possibly saves society in a situation of uncertainty, but it does not guarantee an extraordinary result for one and all. Sooner or later there emerges demand for new ideas: those of development, innovation, patriotism, tradition, social responsibility, justice and the like. But this does not mean that politicians and society will not suffer a relapse.