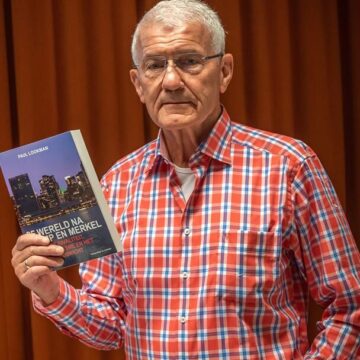

For citation, please use:

Lookman, Paul, 2022. A Future for Europe. Russia in Global Affairs, 20(1), pp. 217-220. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2022-20-1-217-220

Europe’s reliance on the U.S. is no longer sustainable. Glenn Diesen introduces an alternative. If the Russian-Chinese partnership gains sufficient geoeconomic power, it can integrate Europe with Asia into a Eurasian supercontinent. In this scenario the EU can diversify its partners and avoid excessive dependence on one player or region.

In December 2017, more than a year after the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, the Brussels branch of the Spanish think tank Real Instituto Elcano published a Policy Paper[1] in which it presents four scenarios for Europe’s long-term future, both in terms of interaction between EU member states as well as in the relationship with great powers: America, China, and Russia. The underlying question was whether Europe will remain a geopolitical subordinate, or develop into an independent player among the great powers. Elcano had four foreign policy experts draw up a vision of how the future might unfold.

The first scenario depicts Europe as prey to external actors and internal competition. The special relationship with the U.S. is history, NATO passé, and the EU irrelevant. The second scenario, by ULB Professor and Senior Research Fellow at Egmont Institute Alexander Mattelaer, envisions a European Union that will rule Europe and have a significant hand in determining world events. In the third scenario, the West is experiencing a rebirth. The transatlantic framework led by the U.S. and the UK determines the course of events in Europe and how Europe positions itself in the world. Finally, the fourth scenario shows how the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative has brought Europe closer together economically, politically and militarily-strategically.

Europe as western peninsula of Greater Eurasia

In his book, Europe as the Western Peninsula of Greater Eurasia, Norwegian professor Glenn Diesen sees an interesting alternative for Europe. He departs from his theory[2] of the balance of dependency: integration projects can only deliver sustainable mutual economic benefits under a ‘balance of dependence.’ While realism, one of the frames of thought in international politics, suggests that peace requires a balance of power and incentives to maintain the status quo, peace in its geoeconomic equivalent [of realism] requires a balance of dependence. A nation that has strategic industries, transport corridors and financial instruments can use geoeconomic power to gain hegemony or to strengthen sovereignty. Geoeconomic regions with these three pillars acquire collective power.

Diesen outlines how the contemporary West as a region is actually an accident of history. After the devastating World War II, the U.S. was able to strengthen primacy over Western Europe and East Asia through security reliance and geoeconomic control over strategic industries, transportation corridors, and financial instruments. The confrontation with communist rivals softened the geoeconomic rivalry between the U.S. and its dependent allies.

The U.S. will demand great geoeconomic loyalty in its rivalry with China and Russia, to the detriment of the national interests of individual member states.

Global economic power as a geoeconomic region

Diesen’s theoretical introduction leads right to his analysis of developments in the European Union and Eurasia. The world has changed geopolitically and geoeconomically. China is ending the unipolar era and is warming up to geoeconomic leadership. It is making efforts with Russia to integrate Europe and Asia into one Eurasian geoeconomic region. Diesen’s ideas are at odds with traditional thinking in the West. Unlike the fourth Elcano scenario, in which China settles into the center of Europe via a divide-and-rule policy and member states become increasingly dependent, there is no dominant economic power in Diesen’s perspective. Greater Eurasia collectively acquires global economic power as a geoeconomic region.

In Diesen’s book, the Russian-Chinese strategic partnership is at the heart of that Greater Eurasia. Should that partnership acquire sufficient geoeconomic power, it can effectively integrate Europe and Asia into a Eurasian supercontinent. In such a scenario, Europe will be torn between two geoeconomic regions: on the one hand, as a subregion of the transatlantic region, on the other, as part of Greater Eurasia. In order to survive as a geoeconomic region in a multipolar world, the EU, geographically the western peninsula of a future Greater Eurasia, must assert its strategic autonomy and diversify its partners. By doing so, it will avoid excessive dependence on a single state or region.

Positioning between the transatlantic partnership and Greater Eurasia

A region with an integrated economy, equipped with impressive weapons, can quickly shift to competition with economic means. The EU has already taken steps to decouple security from geoeconomics. A majority within the Union has joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and some members have also signed up to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative. A simultaneous partnership with the U.S. and an independent Russia and China policy does not preclude sustainable EU strategic autonomy. Following India’s and Turkey’s template, the best approach for the EU is to seek an independent role between the transatlantic partnership and Greater Eurasia. In a scenario in which a European army provides European security, the EU will take the wind out of the sails of the security guarantee and corresponding geoeconomic power of the U.S.

The European army he proposes perhaps best limits itself strictly to defense. It should neither be able nor willing to replace NATO. In Diesen’s future political

landscape, the transatlantic alliance will gradually lose its relevance, unless the military tug-of-war[3] between the major powers ends in an armed conflict. Diesen’s concept assumes that Brussels will get every EU member on the same page, and that the West will moderate its toxic propaganda against China and Russia. Geopolitics is not about noble ideals like democracy, human rights, or “our way of life,” but about national interests. As far as Europe is concerned, those interests are no longer adequately served in an exclusive Western partnership.

[1] Simón, Luis and Speck, Ulrich (eds), 2017. Europe in 2030. Four Alternative Futures. Real Instituto Elcano,.

[2] Diesen’s theory of the balance of dependence should not be confused with Immanuel Wallerstein’s dependency theory which explains the failure of non-industrialized countries to develop economically. There is some relationship though with the concept of interdependence developed by Norbert Elias.

[3] Menon, Rajan, 2021. Op-Ed: How U.S.-China ‘Competition” Could Lead Both Countries to Disaster. Los Angeles Times, 22 November.