The reunification of Russia and Crimea led to the most serious decline in Russia’s relations with the United States and NATO in recent history. The previous crisis over the conflict in South Ossetia in August 2008 did not trigger such significant consequences, and Russia and the U.S. were able to declare a ‘reset’ in their relations less than one year later. Now, three years after the Crimean events, and despite the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency, a significant warming of Moscow’s relations with Washington and Brussels remains unlikely.

Moreover, the events in Crimea prompted NATO to intensify its military activities in Eastern Europe – a trend that continues to this day. It is therefore necessary to examine this process to determine the nature of the military threats it poses to Russia’s national security.

Russia-NATO Relations After Crimea: Factors Contributing to Tensions

The events in Crimea and Ukraine differ markedly in many ways from the crisis in South Ossetia, making it possible to understand why the U.S. and NATO responded so heatedly to Russia’s actions.

First, the operation in Crimea was Moscow’s preventative reaction to the threat the coup in Kiev posed to Russia’s national interests. This threat, albeit very real, did not in fact materialize at that point. By contrast, the operation for compelling Georgia to make peace was a reaction to a clear and direct military aggression that cost the lives of, among others, Russians serving in a peacekeeping battalion.

Second, Russia’s actions in Crimea altered the strategic and political situation significantly, whereas its intervention in Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008 and the subsequent recognition of their sovereignty were primarily intended to restore and consolidate the status quo that existed before the start of Mikhail Saakashvili’s escapade.

And this leads directly to the third difference. It took less than one month – from Georgia’s invasion to Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and the efficient settlement, whereas the crisis in Ukraine turned out to be very protracted. It has also spread beyond the borders of Crimea and continues to this day as a confrontation between Kiev and the unrecognized People’s Republics of Donetsk and Lugansk.

Finally, the fourth key difference bearing directly on NATO’s military activities is the manifest success of Russia’s military reforms and the resultant increase in the fighting capacity of its Armed Forces.

Strangely enough, the South Ossetia crisis revealed that Russia possessed only a very limited ability to conduct military operations against an enemy of comparable strength, with the Russian army demonstrating technical weakness and organizational sluggishness during the 2008 conflict. The significant losses incurred by the Russian Air Force illustrated this clearly.[1] The success of the Russian operation was largely due to its overwhelming numerical superiority. That is why the events of August 2008 did not raise any red flags for U.S. and NATO military leaders.

Furthermore, Russia’s participation in the Medvedev-Sarkozy peace plan created the illusion among NATO member states that Moscow had backed down under Western pressure – when, in fact, its actions stemmed from the fact that Moscow had pursued only limited political goals in that conflict from the very beginning. As a result, NATO overlooked the most important lesson of that situation – namely, that Russia was prepared resolutely to defend its national interests beyond its borders, including with the use of military force.

The events of February-March 2014 came as an even greater shock. The speed and stealth of the operation caught NATO by surprise, as was admitted most notably by Major-General Gordon Davis, the then-Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations and Intelligence of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe.[2]

This was largely the result of Washington’s sharp drop in demand for military and political expertise on Russia after the end of the Cold War and the consequent general decline in that area of interest. Of course, the U.S. still has many capable Russia specialists, but their ranks have thinned as interest in the study of China and international terrorism has grown and leaders and policymakers seek out their opinions less frequently than before. U.S. military experts with expertise on Russia have focused primarily on nuclear disarmament and missile defence issues. The deeper research into Russia and the former Soviet republics has focused primarily on purely domestic issues. Although the quantity of publications on Russian subjects has increased significantly of late, that process has not shown a corresponding increase in quality. As a result, high quality analytics are often lost amidst a flood of insubstantial or openly tendentious publications.

Washington and Brussels further compromised their ability to gain an objective understanding of the situation by backing themselves into an ‘ideological trap’ through adherence to double standards and a departure from interpreting international processes from a perspective of pragmatic political realism. The West referred to its military interventions in Yugoslavia, Kosovo, and Libya as humanitarian operations and a struggle for democratic values, but branded Moscow’s operations in Georgia as military aggression. It claimed that its recognition of Kosovo’s independence did not violate international law, while Moscow’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia did. This led to demonization of Russia and its foreign policy.

The Baltic countries actively contributed to the ideologically driven and extremely negative perception of Russia among NATO member countries. With no significant military, economic, or expert resources of their own, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia broadcast their own exaggerated fears of Russia and do everything in their power to enlist the U.S. and other leading NATO member countries in support.

Many experts from NATO member countries viewed the operation in Crimea as an example of a successfully implemented fait accompli strategy [3] – that is, as a quick conflict with an extremely insignificant period of threat (that, by the way, is still perceived inaccurately), which forced the U.S. and NATO to resign themselves to the new reality. NATO viewed the operation in Crimea as indicating Russia’s readiness to conduct pre-emptive operations aimed at changing the status quo, even at the cost of a resultant long-term crisis.

For its part, NATO misunderstood the Russian leadership’s motivation and decision-making mechanism and tended to view them in an exclusively negative light. Thus, the Alliance came to characterize Moscow’s policies primarily as hostile and unpredictable.

Indicative of this shift are the spate of studies, such as a recent analysis by the RAND Corporation, pointing out NATO’s unpreparedness for what they see as a possible Russian large-scale military invasion of the Baltic countries. However, they offer no proper analysis of how such an invasion would serve Russia’s national interests. One such study [4] describes Russia’s strategy as an attempt ‘to demonstrate NATO’s inability to protect its most vulnerable members and divide the alliance, reducing the threat it presents from Moscow’s point of view.’ At the same time, the study offers no rationale for why Moscow would be willing to initiate an open conflict with NATO or directly challenge Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty for the sake of such a goal.

A number of considerations – in addition to the external and internal factors already mentioned here – motivated NATO’s actions after 2014. The threat of Russian aggression provides an excellent opportunity for NATO institutions to mobilize, strengthen, and enhance the role of the Alliance; enables the Baltic countries to boost their own importance and develop deeper economic and other ties with the U.S. and other NATO members; makes it possible for the United States European Command to augment its status and the scope of resources available to it; gives the Pentagon a substantially new and more politically convenient argument for increasing its budget than the threat posed by China; and enables the White House to strengthen U.S. influence in Europe and to finally induce its European allies to assume a greater share of the cost of ensuring collective security.

It is worth noting in this regard the imbalance within the NATO bloc between those who supply and those who ‘consume’ security. The U.S. remains the primary supplier of security within NATO, and it successfully uses the worries and fears of the Baltic countries and Norway, the main security ‘consumers’, to achieve its foreign policy goals in Europe – including its objective of deterring Russia.

However, some of the other Western European NATO powers that provide security have demonstrated a lack of interest in returning to Cold War-style conditions and expressed doubts as to the reality of a ‘Russian threat.’ On the one hand, that has helped reduce tensions in Russian-NATO relations, but on the other, it has removed some of the urgency that would otherwise compel those countries to seek compromise solutions to the accumulated disagreements. What’s more, linking the ‘Baltic issue’ with the situation in Ukraine and with other sensitive areas of Russian-U.S. relations such as missile defence and the INF Treaty only complicates this process further. Other ‘consumers’ of security such as the Benelux and Balkan countries also have no direct interest in aggravating relations with Russia, but follow the course of U.S. policy as an expression of solidarity within the bloc.

Strengthening NATO Forces in Eastern Europe

In response to events in Crimea, the U.S. and NATO adopted a number of measures in 2014–2016 aimed at containing a perceived threat from Russia. Former U.S. President Barack Obama launched the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI) in early June 2014. Washington’s initial goal with the ERI was to demonstrate to its NATO allies, primarily in Central and Eastern Europe, its commitment to ensuring their security and territorial integrity. The ERI focused on five main areas of increased U.S. involvement:

- the build-up of the U.S. military presence,

- increased training and exercises,

- pre-positioned equipment,

- infrastructure,

- building partner capacity.

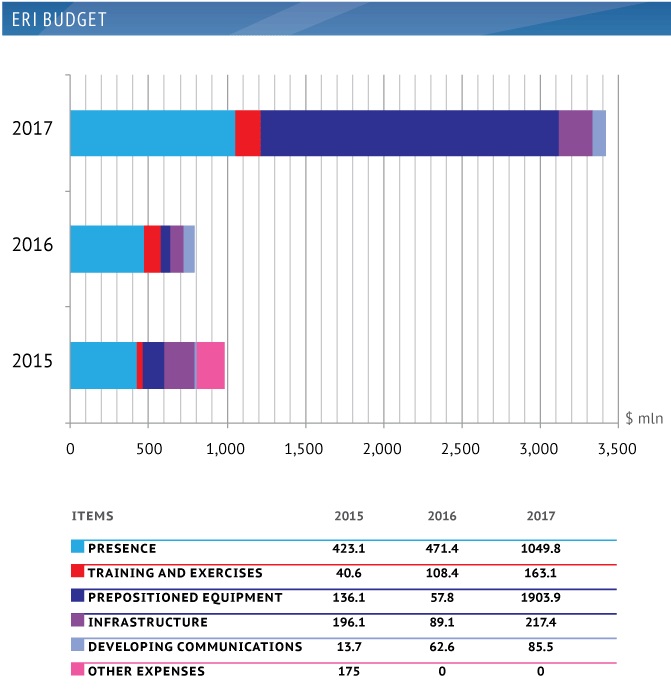

The spending on ERI in the U.S. draft military budget for 2017 was greatly expanded.[5] The task of ‘reassurance’ was augmented by that of deterrence, for which it was decided to finance a number of measures aimed directly at mounting a rapid reaction in a hypothetical event of Russian aggression. Whereas the ERI budget in 2015 stood at $985 million and for 2016 at $790 million, the draft budget for 2017 more than quadrupled to $3.4 billion.[6] Spending to build up military presence more than doubled, exceeding $1 billion, but the main growth stemmed from a $1.9 billion outlay for enhancing the prepositioning of U.S. combat equipment in Europe. This is a sharp increase as compared to the less than $200 million allocated toward that goal in 2015 and 2016.

Spending on the U.S. Army is the largest single expense of the ERI – reaching 83% of the total in 2017, up from 64% in 2016 and 45% in 2015. The draft ERI budget for 2017 provides funding for the combat service of 5,100 military personnel in Europe, 97% of which are U.S. Army military personnel.

The ERI sets out to strengthen significantly the presence of the U.S. Army in Europe. As of May 2016, 25,000 U.S. Army troops were stationed in Europe, 21,000 of which served directly under the EUCOM.[7] These forces are mainly concentrated in Germany [8] (2nd Cavalry Regiment, 12th Combat Aviation Brigade, 10th Army Air and Missile Defence Command (with the SAM Patriot) and in Italy (the 173rd Airborne Brigade).

In 2016, a decision was made within the framework of the ERI to supplement these forces with one U.S. rotational heavy armoured brigade combat team (ABCT) in Eastern Europe. This ABCT is composed of more than 3,500 military personnel and approximately 2,500 pieces of military equipment, including 87 tanks. It will be stationed primarily in Poland, with individual units stationed in the Baltic countries, Romania, Bulgaria, and Germany. The ABCT additionally includes an Army aviation brigade with approximately 2,200 military personnel and 86 helicopters based primarily in Germany. Interestingly, official documents describe the armoured combat brigade as serving the function of ‘reassurance,’ while the aviation brigade is charged with deterrence.

It is worth noting that the U.S. withdrew its 17th and 172nd infantry brigades from Europe in 2012–2013, meaning that the current build-up essentially substitutes one armoured and one aviation brigade for those that were in place prior to 2012.

The ERI has had much less impact on the presence of the U.S.Air Force in Europe. The draft ERI budget for 2017 proposes a temporary suspension of plans to eliminate the 493rd Fighter Squadron with its 20 F-15C aircraft based in Lakenheath, UK. The U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE)[9] currently have six fighter squadrons – three in the 48th Fighter Wing in the UK, one in the 52nd Wing in Germany, and two in the 31st Wing in Italy. The USAFE also includes one squadron of KC-135 Stratotankers in the UK (part of the 100th Wing) and one squadron of C-130 Super Hercules military transport aircraft (as part of the 86th Wing of military transport aviation).

The ERI does not call for a build-up of the naval presence in Europe. In its area of responsibility, the U.S. Sixth Fleet has only five permanent ships [10] – its flagman, the USS Mount Whitney (LCC-20) based in Italy and four destroyers deployed in Spain as part of the European Phased Adaptive Approach for missile defence. Other U.S. Navy ships also rotate through the Sixth Fleet’s zone of responsibility. The aircraft carrier strike group that constitutes the backbone of the U.S. fleet maintains a very limited presence in the region, usually only passing through as it moves between the Fifth Fleet and the continental U.S. The number and movements of U.S. submarines in the region remain secret.

As mentioned earlier, the creation of prepositioned forces accounts for most of the increase in the ERI budget. Current plans call for placing such forces in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and possibly Poland, and formation of two ABCT, logistical support brigades, and artillery brigades. During a crisis or period of threat, these reserves would enable the U.S. to deploy fairly quickly a division-sized unit of its 4th Infantry Division based in Germany that can operate in high intensity conflicts.

The ERI also contains numerous and varied individual measures for enhancing the Air Force (such as modernizing airfield infrastructure and creating aviation munitions reserves), reconnaissance and surveillance, as well as special operations forces. These are largely aimed at preventing a surprise invasion by Russia.

At the same time, similar measures are implemented within the framework of NATO. A decision reached at the NATO summit in Wales in September 2014[11] resulted in developing a Readiness Action Plan. In particular, a decision was made to significantly strengthen the NATO Response Force by expanding its ranks to 40,000 troops and to create, within that formation, a Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF) capable of deploying within 48–72 hours.[12]

The VJTF will consist of 20,000 troops, including a multinational land brigade of 5,000. The VJTF will also be supplemented with two multinational brigades that require more time to deploy, and with various command and logistical elements, air and naval forces, and Special Operations Forces. Small command elements called NATO Force Integration Units were created in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, the Baltic countries, Hungary, and Slovakia in order to facilitate the deployment of the NATO Response Force in the event of a crisis, and to coordinate actions between national armed forces, including periods of training manoeuvres.

The exact composition and actual battle readiness of the NATO Reaction Force and VJTF remain unknown. However, considering their multinational character and the attendant organizational and logistical difficulties that entail, the battle effectiveness of the Reaction Force and VJTF is probably lower than what analogous forces composed of troops from a single country could possess.

At its Warsaw summit in July 2016, NATO adopted a number of additional measures to combat the notorious ‘Russian threat.’[13] As part of the Enhanced Forward Presence program, it was decided to deploy four multinational battalions in Poland and the Baltic countries.

The United States will be responsible for deploying to Poland while the United Kingdom, Canada, and Germany are charged with deploying to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania respectively.

Those forces total approximately 4,000–5,000 personnel. In the event of a major conflict, the small size and locations of these battalions would reduce their military importance and leave them vulnerable when carrying out preventive or preemptive strikes. Rather, they play primarily a political role by demonstrating the presence of multinational forces in the Baltic countries and NATO’s willingness to uphold Article 5 of its Treaty.

NATO intensified its training manoeuvres in 2015–2016. The Noble Jump 2015 exercises held in June of that year, in which approximately 2,000 troops from nine countries took part, included efforts at streamlining the deployment of the VJTF.

Trident Juncture, major military manoeuvres conducted in October-November 2015, rehearsed mechanisms for deploying both the VJTF and the NATO Rapid Response Force. Those exercises were held in Spain, Italy, and Portugal, with the participation of approximately 36,000 personnel, four multinational brigades, approximately 190 aircraft, and approximately 70 ships and submarines.

Poland also conducted its own Anakonda Exercise in June 2016 in which 31,000 military personnel, including 14,000 U.S. and 12,000 Polish troops, participated.

NATO Military Spending

The U.S. and NATO have been intensifying their military operations in Europe and individual NATO member states have announced decisions to increase their military spending. According to official estimates, NATO defence expenditures totalled approximately $921 billion.[14] The United States paid the lion’s share of that sum, contributing 72% of the total. Only three other members of the NATO bloc spend more than $40 billion annually on defence – the United Kingdom ($56.8 billion), France ($44.2 billion), and Germany ($41.7 billion). Together, they contribute 15.5% toward overall NATO defence expenditures. Another four countries – Italy, Canada, Turkey, and Spain – spend at least $10 billion on defence – $22.1 billion, $15.5 billion, $12 billion, and $11.2 billion, respectively, contributing 6.6% toward overall expenses. The remaining NATO member countries combined contributed less than 6% to total military outlays.

Canada and all European NATO member countries except the UK reduced their annual military spending by 1–3% from 2009–2014. According to data for 2016, among key countries, in absolute terms, only the U.S. and the UK [15] fulfilled the requirement to allocate not less than 2% of GDP to defence. Out of the key NATO countries in terms of military spending, only the U.S., the UK, France, Italy, and Turkey fulfilled their obligation to devote not less than 20% of their total military outlays to the purchase of arms and military equipment.[16]

At the NATO summit in Wales, it was decided that members of the bloc that are not ful?lling the military and arms procurement spending requirements would stop cutting back those expenses and strive to meet the 2% / 20% requirement by 2024. And indeed, spending did increase by 0.5% in 2015 and by 3.8% in 2016.

The Donald Trump administration is trying to persuade Washington’s NATO allies to meet the 2% of GDP military spending requirement. Given that the European NATO countries currently spend 1.47% of their combined GDP on defence, or $241.8 billion, ful?lling that pledge would mean a 36% larger outlay, or an additional $87 billion at current GDP levels. Germany would have to provide the largest share of that increase by expanding its military budget by 67%, or by $28 billion to meet this goal.[17] If it does so, it would place second after the U.S. for military spending on NATO. As for the other key countries, France, Italy, Turkey, Spain, and Canada would have to increase their military spending by 12% ($5.3 billion), 80% ($17.7 billion), 18% ($2.2 billion), 122% ($13.7 billion), and 96% ($14.9 billion) – respectively.

By comparison, Russian military spending in 2016 totalled approximately 3.8 trillion roubles [18], or approximately $63 billion.[19] That figure represents 4.5% of Russia’s GDP, but it includes 800 billion roubles ($13 billion) that represents the 1% of GDP that the state allocated to repay loans incurred by companies of the military-industrial complex. Excluding these significant expenses, Russia’s military budget equals only 5.4% of the total military expenditures of NATO member countries. Moreover, while NATO is striving to increase its military spending, Russia plans to maintain its level of spending at 2.7–2.8 trillion roubles per year.

The disproportion becomes even more acute between NATO’s planned increase in military spending and the decrease in the intensity of Russia’s military construction – associated with the completion of major programs for modernization and upgrading of its Armed Forces.

Donald Trump made a campaign promise to develop, modernize, and ‘restore’ the U.S. Armed Forces. His administration has pledged to eliminate the military spending caps imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 and to increase the size of the Armed Forces. The most famous and striking of such statements was the promise to increase the U.S. Naval fleet from the current 275 ships to 350.[20]

Still, the planned increase in U.S. military spending may only become a threat if it can overcome the significant obstacles blocking its realization. First, Donald Trump will find it a daunting task to expand the military budget significantly while making good on other election promises such as the pledge to cut specific taxes. The new administration will have to find a source of funding to build up the military. Any attempt to cut non-military spending or increase the national debt would meet strong opposition from the Congress.

Second, if the U.S. actually does increase defence spending, it would make sense to expand the number of military personnel only after restoring the overall combat capability of the Armed Forces first. The U.S. Armed Forces have been functioning under a heightened operational load over the past 15 years, the result of maintaining the global presence and participating in numerous operations, of which those in Iraq and Afghanistan are merely the largest. Other factors also contribute to this situation:

- the long-term impact of sharp reductions made in the 1990s to military spending and the procurement of arms and military equipment;

- restrictions on military expenditures made in the 2010s;

- a number of major programs that were completed only after significant cost overruns and delays (such as the F-35 fighter aircraft or the new Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carrier);

- a number of major programs that, after receiving considerable resources, were shelved or scaled back substantially (such as the construction of Zumwalt-class destroyers);

- the need for very costly modernization of strategic nuclear forces (with a price tag of up to $400 billion in 2017–20126, of which the Defense Department will have to pay $267 billion [21]).

As Deputy U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Work stated last December [22], the Pentagon will have to spend approximately $88 billion annually in additional outlays in the coming years (approximately 16% above the basic Fiscal Year 2017 military budget, excluding overseas operations [23]) in order to restore the combat capability of the Armed Forces, and for a number of other priority measures. Expanding the numerical strength of the Armed Forces would require an even more substantial outlay. That is why, for the U.S., greater military spending by its European allies and Canada would ease some of the financial burden on its own military budget – especially considering that Europe remains the third highest priority in Washington’s military-political strategy, after the Middle East and the Western Paci?c. It is noteworthy that experts at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment (CSBA) suggest that the Western Paci?c should be the top priority for the U.S. military build-up, followed by Europe and the Middle East.[24]

Threats to Russia

Russia has actively developed its Armed Forces in recent years. Priority areas include the Arctic and Crimea, but it has built up its military contingent most intensively in the southwest, on the border with Ukraine. There, Russia has augmented existing brigades with the creation of three new motorized infantry divisions: the 144th in the Smolensk and Bryansk regions, the 3rd in the Voronezh and Belgorod regions, and the 150th in the Rostov region. It also renewed the 1st Armoured and 8th Combined Arms armies in Odintsovo and Novocherkassk respectively, and the command for the 20th Combined Arms army has been returned to Voronezh.

The reasons for this process are obvious: until recently, Russia had only very limited forces on its border with Ukraine. Now, given the tense relations with the current authorities in Kiev and the continuing conflict in Donbass, Moscow must take measures to shield this strategically important area and to create the capacity to respond in the event of a crisis.

The forces in other military districts are also undergoing reorganization. For example, the 90th Armoured Division was restored in the Chelyabinsk region of the Central Military District, and the 42nd Motorized Infantry Division in the Chechen Republic of the Southern Military District. It should be emphasized that many of these decisions are aimed rather at halting reduction and reorganization of the Armed Forced, situation caused by the military reforms of the late 2000s and early 2010s – than at their build-up. The reasons for this are also clear: the Ukrainian crisis and Moscow’s disappointment with the failure of the ‘reset’ in Russian-U.S. relations.

In contrast to its active build-up of military forces in the south and the north, Russia has shown a noticeable lack of desire to strengthen its military presence in the immediate vicinity of the Baltic countries – that is, in the Novgorod, Pskov, and Kaliningrad regions, with no significant build-up of Russian forces occurring in those regions. Combat strength remains at approximately the same level there, with the exception of certain reorganizational measures. For instance, a command structure for 11th Army Corps and the 7th Motorized Artillery Guards Regiment was reassigned the status of a brigade. Rearming and introducing modern military equipment to forces in the three regions of northwest Russia has been proceeding very slowly.

The poor condition of the Baltic Fleet deserves mention here. Nearly every Baltic Fleet commander, including Commander Vice Admiral Viktor Kravchuk, was dismissed in June 2016. They were faulted for ‘serious shortcomings in the organization of military training and the daily operations of troops, failure to take all necessary measures to improve living conditions for troops, a lack of concern for subordinates, as well as the distortion of the real state of affairs in reports.’[25] And this year, Baltic Fleet Military Investigation Department head Major General Sergey Sharshavykh noted that the number of military service crimes in the Baltic Fleet had surged from 9 to 133 cases. [26] It is difficult to imagine that Moscow could be planning to start a conflict with NATO given such a state of affairs in one of the key elements of Russia’s military in the northwest region.

Belarus is another factor. Minsk currently maintains an ambivalent position, in both political and military terms. On the one hand, Russia and Belarus enjoy close political and economic ties. Minsk generally follows Moscow’s military and political strategy and shares its concerns over NATO activities – as Belarusian Defence Minister Lieutenant General Andrei Ravkov noted in a recent speech.[27] On the other hand, Minsk tries to pursue an independent foreign policy, avoiding open confrontation with the West while declining to extend unconditional support for Moscow. This finds particular expression in its unwillingness to recognize the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, its very cautious stance on the issue of Crimea [28], and its occasional disagreements with Russia.

Moreover, Russia does not have a significant military presence in Belarus, maintaining only a Russian Volga-type radar missile-warning system and a Russian naval communications centre there. Plans to create a Russian air base in Belarus have not been implemented.[29]

Despite this, the West considers Belarus as a Russian ally and a strategically important staging area for deployment in the event of a hypothetical invasion of the Baltic states.[30] The thinking is that Belarus could participate directly in such an invasion, using its forces in combination with those in Kaliningrad to take control of the so-called Suwalki Gap, thereby cutting off the Baltic countries from the rest of Europe.

In fact, Belarus does serve as a buffer zone between Russia and NATO, and it would be highly disadvantageous for both sides were that status quo to change. Brussels would undoubtedly view the deployment of a large Russian contingent in Belarus as a direct threat. For its part, Russia would find it completely unacceptable were Minsk to break off relations with Moscow or, conversely, if NATO were to apply military and political pressure on Belarus.

Central Asia and the Far East are of only secondary concern, whereas Ukraine, the Arctic, and Crimea are currently Russia’s top priorities for developing its Armed Forces. It is the latter three that the Russian leadership considers the main subject to its national security threats and where it feels its military capabilities are lacking. Moscow has made it very clear that it does not want any further deterioration in relations with NATO, much less a military conflict with the bloc. However, the measures adopted by NATO and the U.S. – including the ERI, the staging of major military exercises close to Russia’s borders, and the decision by NATO’s European member countries to increase military spending significantly – heighten the security threat to Russia in general and to the Kaliningrad exclave in particular.

Despite the increase in NATO activity, the risk level remains low at present. The decision to place pre-positioned military equipment in Europe was something of a compromise. It permitted the U.S. to increase its military potential in the region and ease the concerns of its European allies at a relatively limited expense in resources while creating far less of a threat for Russia than deployment of a full division of its forces would have done. The current U.S. presence in Europe is comparable to where it stood in 2011.

At the same time, plans by NATO’s European member countries to increase military spending could exacerbate tensions between Russia and the Alliance even further. However, many questions remain open: Will military spending actually increase, and if so, to what extent? How would such an increase change the structure of the Armed Forces of the leading NATO member countries of Europe? To what extent would an increase in spending heighten the combat capability and readiness of NATO forces? Could the NATO countries interact effectively in the eastern region?

Nonetheless, if the U.S. and NATO continue increasing their activity near Russia’s borders, it could increase the level of threat to Russia. Yet, this is precisely what some experts are calling on Washington to do. For example, representatives of the RAND Corporation claim that NATO is ‘unprepared’ for war with Russia on the territory of the Baltic countries and propose that the U.S. and NATO deploy substantial additional military contingents – up to 21 brigades, in addition to artillery and aviation.

Were that to happen, Russia would have to take extra measures to ensure the security of its northwestern borders. As a result, Russia and NATO would wind up as hostages of a security dilemma, and the risk of conflict would rise, instead of fading away altogether. Moscow is trying to prevent this, but it is not willing to go so far as to abandon all efforts to parry threats to its own security, including those connected with Ukraine. Furthermore, the status of Crimea is entirely non-negotiable. The failure to understand this and NATO’s reluctance to hold pragmatic negotiations with Moscow could lead to a number of problems for Europe.

The situation remains far from critical, and the political dialogue between Russia and NATO has improved recently in several areas.[31] In addition, Chief of the Russian General Staff, Army General Valery Gerasimov held a telephone conversation with NATO Military Committee Chairman General Petr Pavel. This was the first high-level contact between military officials since NATO decided to freeze relations with Russia.[32] General Gerasimov also continues to have contact with U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General John Dunford. Intensifying the dialogue between Russian and NATO military officials and diplomats could facilitate an easing of tensions and make it possible to reach a mutually beneficial solution to existing problems.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai Discussion Club

[1] Mikhailov, A, 2009, ‘Piatidnevnaia voina: itog v vozdukhe’ [The five-day war: results in the air space], Vozdushnokosmicheskaia oborona, 30 January. Available from: http://www.vko.ru/voyny-i-konflikty/pyatidnevnaya-voynaitog-v-vozduhe

[2] ‘NATO General: West Won’t Be Caught Off Guard by Putin Again’, 2015, PRI and WNYC, 20 March. Available from: http://www.wnyc.org/story/nato-intelligence-general-says-west-caught-guard-annexation-crimea/

[3] Painter, S & Henning JC, 2014, ‘Crimean Crisis Plan: Negotiate With Russia, Expand NATO, Give Ukraine Time’, Breaking Defense, 21 March. Available from: http://breakingdefense.com/2014/03/crimean-crisis-plan-negotiatewith-russia-expand-nato-give-ukraine-time/

[4] Shlapak DA & Johnson M, ‘Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank’, RAND Corporation. Available from: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1253.html

[5] ‘European Reassurance Initiative. Department of Defense Budget. Fiscal year 2017’, 2016, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), February. Available from: http://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/ defbudget/fy2017/FY2017_ERI_J-Book.pdf

[6] It is worth noting that the ERI is financed from the Overseas Contingency Operations budget, meaning that is not subject to the restrictions that the Budget Control Act of 2011 imposed on the main U.S. military budget.

[7] ‘History fact sheets’, United States European Command (EUCOM). Available from: http://www.eucom.mil/about/history/fact-sheets

[8] ‘Units and Commands’, United States Army Europe. Available from: http://www.eur.army.mil/organization/units.htm

[9] Units, U.S. Air Forces in Europe & Air Forces Africa. Available from: http://www.usafe.af.mil/Units/

[10] ‘Our Ships’, U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa / U.S. 6th Fleet. Available from: http://www.c6f.navy.mil/ organization/ships

[11] ‘Wales Summit Declaration’, 2014, NATO, 5 September. Available from: http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/ official_texts_112964.htm

[12] NATO’s new spearhead force gears up. Available from: http://www.nato.int/cps/eu/natohq/news_118642.htm

[13] ‘Warsaw Summit Communiqué’, 2016, NATO, 9 July. Available from: http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_ texts_133169.htm

[14] ‘The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2016’, NATO, 13 March. Available from: http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_142149.htm Hereinafter NATO financial figures are in current prices.

[15] Greece, Estonia, and Poland also fulfilled the ‘2% of GDP’ requirement.

[16] Luxembourg, Lithuania, Romania, Poland and Norway also fulfilled the ‘20% of military spending’ requirement.

[17] Hereinafter, approximate figures are figures are used for NATO countries, based on their current GDP.

[18] ‘Obzor ekonomicheskikh pokazatelei’ [Overview of economic indicators], 2017, Expert Group on economy, Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation, 23 January. Available from: http://www.eeg.ru/downloads/obzor/rus/pdf/2017_01.pdf

[19] At an exchange rate of 60 rubles per dollar.

[20] ‘Status of the Navy’, 2017, Department of the Navy of the U.S., 23 June. Available from: http://www.navy.mil/navydata/nav_legacy.asp?id=146

[21] ‘Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2017 to 2026’, 2017, Congressional Budget Office, February. Available from: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/115th-congress-2017–2018/reports/52401-nuclearcosts.pdf

[22] Eckstein, M, 2016, ‘DEPSECDEF Work Cautions Trump Team Against Growing Military Size Over Capability’, U.S. Naval Institute News, 6 December. Available from: https://news.usni.org/2016/12/06/depsec-work-cautions-trumpteam-against-growing-military-size-over-capability

[23] ‘America First. Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again’, Executive Office of the President of the United States, Office of Management and Budget. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/2018_blueprint.pdf

[24] Krepinevich, AF, 2017, ‘Preserving the Balance. A U.S. Eurasia Defense Strategy’, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Available from: http://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/CSBA6227PreservingTheBalance_PRINT.pdf

[25] ‘Komanduiushchego i nachal’nika shtaba Baltflota otstranili posle inspektsii’ [The Commander and Chief of Staff of the Baltic Fleet suspended after inspection], 2016, Interfax, 29 June. Available from: http://www.interfax.ru/ russia/516024

[26] ‘Glava Voenno-sledstvennogo upravleniia po Baltflotu general-maior iustitsii Sergei Sharshavykh: ‘Voinskie prestupleniia negativno vliiaiut na boegotovnost’’ [Military Investigation Chief for Baltic Fleet Gen-Maj Sergey Sharshavyh: “Violations in military have negative effect on combat efficiency], Interfax – Military news agency. Available from: http://www.militarynews.ru/story.asp?rid=2&nid=443536

[27] ‘Vystuplenie Ministra oborony Belorussii general-leitenanta Andreia Ravkova’ [Speech of Belarussian Defense Minister Gen-Lieut Andrey Ravkov], 2017, Defense Ministry of Russia, 26 April. Available from: https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=3ZCyh5ew1f8&feature=youtu.be

[28] Samozhnev, A, 2016, ‘Minsk ne stanet dreifovat’’ [Minsk will not drift], Rossiiskaia gazeta, 8 April. Available from: https://rg.ru/2016/04/08/reg-kfo/glava-mid-belorussii-priznal-fakticheskij-status-kryma.html

[29] ‘Lukashenko ob’iasnil, pochemu otkazal Rossii v sozdanii voennoi aviabazy v Belorussii’ [Lukashenko explained his rejection of Russian plans to establish a military air base in Belarus], 2017, Rosbalt, 3 February. Available from: http://www.rosbalt.ru/world/2017/02/03/1588871.html

[30] Edelman, E & McNamara WM, 2017, ‘U.S. Strategy for Maintaining a Europe Whole and Free’, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 16 February. Available from: http://csbaonline.org/research/publications/u.s.-strategyfor-maintaining-a-europe-whole-and-free

[31] The Russia-NATO Council met three times in 2016, and the UN Secretary-General has met twice with the Foreign Minister of Russia.

[32] ‘Nachal’nik General’nogo shtaba Vooruzhennykh Sil RF general armii Valerii Gerasimov provel telefonnyi razgovor s predsedatelem Voennogo komiteta NATO generalom Petrom Pavelom’ [Chief of the Russian General Staff Gen Valery Gerasimov holds a phone talk with NATO Military Committee Chairman Gen Petr Pavel], 2017, Defense Ministry of Russia, 3 March. Available from: http://function.mil.ru/news_page/person/more.htm?id=12113548@ egNews