This article summarizes the results of research conducted with financial support from the Russian Foundation for the Humanities.

As major pillars of collective identity, conventional conceptions of the past play an important role in modern political communities. Public history – distinguished from professional history as official interpretations of past events addressed to a broad public – is a central element of symbolic politics, which is targeted at building collective solidarity and forming an idea of ‘We’ in society. This aspect of symbolic politics is relevant for constructing all kinds of group identities, but it is particularly crucial in nation-building. Therefore it is not accidental that modern historiography is largely centered on writing histories of nation-states.

SYMBOLIC POLICY: A CASE FOR RUSSIA

After the collapse of the Soviet Union all the newly independent states faced the problem of building national identities within new boundaries. In Russia’s case this task was complicated by several factors. First, uncertainty flourished about the geopolitical and cultural boundaries of the macro-political community that constituted the new Russian state. Second, the Soviet tradition of institutionalizing ethnicity inhibited an understanding of identity for this macro-political community as a nation. Efforts to form national solidarity based on ethnic and confessional principles raised concern about “violating the rights of nationalities” that formed the “multinational” Russian state. Third, in the new international environment, an interpretation of ‘significant others,’ against which the new Russian identity was defined, also became controversial. Unlike most post-Communist countries, Russia found it difficult to find ‘significant others’ who could be blamed for the troubles and hardships that Russians were experiencing. Fourth, the federal structure of post-Soviet Russia had far fewer resources for shaping a uniform identity than other “national” post-Soviet states. All of this meant that self-identification with the new Russian state was not easy from the very beginning. Of course, a variety of symbolic traditional resources could be used to shape the new Russian identity, but this legacy was overburdened by dramatic conflicts. In particular, there were no “ready” versions of a historical narrative that could be used as a foundation for the new national identity, while attempts to reinterpret the collective past caused heated debate. Finally, an ideological rift in the 1990s slowed the emergence of new models of collective identity that would help solidarity overcome political distinctions. Thus, the formation of a new macro-political identity in post-Soviet Russia followed a rather contradictory and intricate path.

This article discusses a particular aspect of this multifaceted problem – political references to the past in the context of symbolic politics aimed at (re)constructing the national idea of ‘We’ in Russian society. A reconsideration of the major narratives of the collective past is an important element in nation-building and it suggests a choice between different options for interpretation and evaluation. Many scholars consider the unpreparedness of the Russian political and intellectual elites to make such a choice to be the central problem of Russian political identity today. This issue is closely related to the continuing uncertainty over the crucial questions “Who/what are ‘We’?” and “Who belongs to ‘Us’?”.

Political references to history in the context of establishing national identity are an important aspect of symbolic politics. Our understanding of the term follows Pierre Bourdieu’s concept in which symbolic politics is considered as a political activity aimed at producing and promoting certain modes of interpreting social reality and ensuring the dominance of these methods.

The state is not the only player in the symbolic political arena, but it occupies a special position. The federal government is able to impose certain interpretations of social reality on society by using administrative resources (implementing educational standards) and legal measures (citizenship laws); by assigning a special status to particular symbols (establishing public holidays, official symbols, state awards, etc.); and by representing society on the global stage. Consequently, public statements by official representatives who speak “for the state” and make decisions acquire special significance and serve as reference points for other participants in political discourse. It should be mentioned that official symbolic policy might be inconsistent and context-dependent: those who speak “for the state” do not always rely on systemic interpretations of social reality and frequently have to react to current conflicts. In spite of the powerful resources that the state has at its disposal, the dominant official interpretations of social reality that it promotes are not predetermined: even in totalitarian and authoritarian societies where certain normative principles are imposed by force, there are still opportunities for escape, such as “roguish adaptation” and “double thinking.”

Symbolic politics takes place in the public sector, i.e. in the virtual space where socially significant issues are discussed, public opinion is formed, and collective identities are (re)defined. In other words, this is a sector where different interpretations of social reality compete. The configuration of institutions and practices of a particular public sector determine both the opportunities and strategies of those who shape symbolic politics.

This article traces several tendencies in post-Soviet Russia in the political use of the past in official symbolic politics. I analyze State of the Nation addresses by Boris Yeltsin, Vladimir Putin, and Dmitry Medvedev, as well as several complementary texts. As official strategic documents covering approximately the same range of political issues, annual State of the Nation addresses are particularly helpful for studying shifts in the official presentation of and justification for a political course. The documents for this study are relevant because they reflect major trends in using (or not using) the past to legitimize power.

REPRESENTING THE COLLECTIVE PAST: STATE OF THE NATION ADDRESSES, 1994-2010

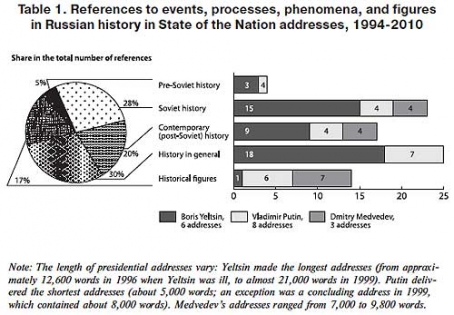

All Russian presidential addresses refer to the national past for a variety of reasons. The greatest number – 46 references to various events, processes, phenomena, and figures in Russian history – were found in six addresses by Boris Yeltsin; 22 references were uncovered in eight addresses by Vladimir Putin; and 15 were noted in three addresses by Dmitry Medvedev. Although Yeltsin’s addresses were typically twice as long (or more) as those of his two successors, the main reason for his numerous references to the past is that he consistently represented himself as a political leader who changed the course of Russian history: “The major job of my life is finished. Russia will never regain its past – Russia will always move only forward. And I shall not stand in the way of this natural flow of history.”

It seems that Yeltsin had a special and intimate attitude towards history, while the approaches of Putin and Medvedev are not as emotional. Yet the most significant differences between the addresses concern particular references to the past and its interpretation.

Presidential addresses have included references to historical figures, mostly from culture and science, since 1999, when Yeltsin quoted Alexander Solzhenitsyn about the need “to save the people,” suggesting that this could become Russia’s “national idea.” Putin referred to the philosopher Ivan Ilyin (twice), the scholar Dmitry Likhachev (three times), and Solzhenitsyn (again in the context of “saving the people”). Dmitry Medvedev mentioned Pyotr Stolypin, Boris Chicherin, Vassily Leontyev, Nikolai Nekrasov, Anton Chekhov, Yuri Gagarin, and Anna Akhmatova. Analysis shows that there is an obvious tendency to appeal to modern (and even recent) history rather than to reinterpret a previous era.

References are not uniform with regard to historical periods (see Table 1); specific events, processes, and phenomena are mentioned more in the Soviet (28%) and post-Soviet (20%) periods. Only five percent of references relate to the pre-Soviet period.

Politicians refer to the past for different reasons in discussions of political strategy. The most important goals are to demonstrate continuity between the past and the present (legitimization by tradition) and to highlight differences between the present and the past for the benefit of either the former (to underscore present achievements) or the latter (usually to justify the need for change or to explain the reasons behind current difficulties and failures).

BORIS YELTSIN

The theme of continuity/discontinuity of tradition prevails in references to the past in Yeltsin’s addresses. Specifically, the reforms started under his leadership were portrayed as the restoration of continuity in national history that was interrupted during Soviet rule: “The totalitarian ideology… which dominated for decades, has collapsed. Instead, an awareness of a natural historical and cultural continuity is coming” (1994).

Yeltsin’s addresses often describe the present in a more positive light than the past (16 out of 46 references are critical). “Now as never before Russians have broader opportunities to share the original values of Russian and world culture” (1995).

Yeltsin’s critical assessments mostly concerned the Soviet legacy and he blamed this legacy for the “super-strict mobilization model of development,” the “stagnant economic system,” and the “annihilation of civil society, nascent democracy, and private property” (1996). In addressing the recent Soviet past, Yeltsin wanted to justify his own policy, explaining the dire need for radical and traumatic reforms as the result of “problems that Russia had inherited from the past” (1996). In this way Yeltsin wanted to share the responsibility for unpopular reforms with the Soviet leadership. This is the main reason for the large number of critical assessments in referring to reforms during the Khrushchev era and perestroika.

But the root of many problems today lies in pre-Soviet history: “Tsarist Russia, overwhelmed by the burden of its own historical problems, failed to enter the path towards democracy.” This fact determined “the radicalism of the Russian revolutionary process” and finally resulted in the break with historical tradition (1996).

The new political tasks were conceived of as a change of tradition rather than continuity. At the end of the 1990s Russia was represented not as a common denominator of previous historical experience, but as a new Russia. The ruling elite in the 1990s (un)consciously interrupted tradition by rejecting the previous era’s values and objectives.

There were relatively few positive moments in the national past that Yeltsin mentioned in his addresses. Yeltsin pointed out Russia’s ability to overcome difficulties, the great potential of its people, the country’s ability to preserve its best qualities (through diligence and talent) in spite of overwhelming odds (1996), and Russia’s immunity to pessimism (1999). Only once, in 1996, were democratic principles recognized as part of Russian historical heritage: “The traditions of people’s rule is an innate part of the Russian people” (1996).

Although Yeltsin mentioned Russia’s pre-revolutionary history more often that Putin and Medvedev did, his appeals to restore historical and cultural continuity were not supported by references to concrete elements of Russia’s historical heritage, which modern Russia should rely on. The tendency to use the past by contrasting it with the present clearly prevailed over a desire to firmly establish a political course steeped in national history.

VLADIMIR PUTIN

Putin continued to develop the topic of continuity and change. Remarkably, in his first address Putin said: “Today, when we go forward, it is more important to look to the future than to remember the past” (2000). A year later, however, he turned to history to authenticate stability, the key principle of his political course, incorporating it in the historical context “… revolution is usually followed by counter-revolution, reforms – by counter-reforms… But… this cycle is over, there will be no more revolutions nor counter-revolutions” (2001). Thus Putin also represented his course as a new path, one that was not typical of the Russian historical tradition. Whereas for Yeltsin the Soviet period was the main point of reference in the context of legitimizing the political course (totalitarianism and perestroika as “a failed reform”), for Putin it was the 1990s (see Table 1). He contrasted his policy of “stability” to the radicalism of the previous decade.

Remarkably, Putin’s references to the 1990s changed with time. In his 2004 address, along with a critical assessment of the 1990s, Putin defined this period as the beginning of a long and difficult process, a stage of “dismantling the former economic system.” In 2005, Putin stepped up his attacks and directly targeted the authorities (“groups of oligarchs… served exclusively their own corporate interests” (2005)), instead of the problems society faced, as was the case in his 2004 address.

Therefore, on the one hand Putin confirmed the continuity of the political course and his commitment to the ideals of the 1990s. On the other hand, he insisted that Russia should take another path from that of the previous decade and emphasized the difference in the methods used to implement the task.

Putin’s addresses during his second term also reveal a change in his attitude towards the Soviet past. In 2000, Putin was ready to adopt several Soviet state symbols, including “the old national anthem” (although with new lyrics) and the Soviet flag for the military. However, in his 2005 address, Putin made a sensational statement and said the collapse of the Soviet Union was “the largest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” (which contrasted with Yeltsin’s repeated sharp interpretations). This statement should be looked at as a shift in the interpretation of the imperial past, which had become especially evident by the mid-2000s.

In the same address, delivered just two weeks before the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II, Putin presented the meaning of the victory in broad humanistic terms. He defined the Soviet Union’s victory as “the day civilization triumphed over fascism,” and described the Red Army as “soldiers of freedom.” This interpretation could be viewed as a further development of the thesis announced a few minutes earlier concerning Russia’s commitment to European values: “For many centuries the values of freedom, human rights, justice, and democracy, achieved through much suffering by European culture, were a key point of value reference for our society” (2005).

Since the mid-2000s, the topic of World War II has played a key role in Russia’s symbolic politics with regard to foreign countries and it has turned into an object of competing interpretations.

The addresses of all three presidents frequently mention World War II. The context of these references is different: in some cases the references are related to current political and social problems, such as fighting extremist organizations (in 1995), providing pensions to veterans (in 1995), maintaining the armed forces (2006), or the patriotic education of the young generation (2010). In the other cases references to World War II are embodied with a special symbolic meaning, like in the 2005 address quoted above. Remarkably, Medvedev also contributed to the symbolic use of the war theme, interpreting it as a pledge of success for Russia’s modernization: “We are of the same blood with those who won the victory, so we all are their heirs; that is why I believe in the new Russia” (2009)).

In eight of Putin’s addresses there are seven more references to history as a continuing tradition. What aspects of tradition were significant for the legitimization of Putin’s political course?

First, the idea of a “strong state” as the basis for Russia’s past and future greatness. In his 2003 address, Putin spoke of Russia’s ability as a heroic deed to “maintain the state in a vast space, a unique community of people and – at the same time – [preserve] the country’s powerful position in the world.” However, in the public discourse, Russia’s vast territory is interpreted both as a sign of greatness and as a source of problems, particularly as a factor determining the costly mobilization economic development model. By referring to Russia’s “continued reproduction of itself as a strong state” (2003), Putin was clearly legitimizing his course for “strengthening the state” through national historical tradition.

Second, the idea of unity as a principle that limits political competition. The main goal of Putin’s symbolic policy was a call for “consolidation.” In his first State of the Nation address, Putin, speaking about Russia’s unity (“fastened by patriotism, cultural traditions, and a shared historical memory that is peculiar to the people”) specified his position: “In spite of many views, opinions, and a diversity of party platforms, we have always had common values” (2000). Putin reiterated this position in 2008: “Political parties must be aware of their great responsibility for… unity of the nation and stability of the development of our country. However heated political battles may get … they are never worth bringing the country to the brink of chaos.”

DMITRY MEDVEDEV

Although Medvedev did not refer to the past very much in his addresses, the times he did do so appear to be more significant, since he rarely defined ‘Us’ against the ‘Others’ (by which Russians usually mean the West). The second specific feature of his approach to the past is a critical assessment of tradition. In fact, Medvedev proclaimed a selective approach to tradition. In his 2009 article Russia, Forward! Medvedev explicitly stated that “not all traditions are useful” and some of them should be “gotten rid of resolutely.” He also provided examples of wrong traditions that were successfully eliminated: “Serfdom and widespread illiteracy once seemed irresistible. But they were overcome.” The same interpretation of tradition is present in Medvedev’s presidential addresses. In 2008, he expressed regret that “over centuries the cult of the state and the pseudo-wisdom of the executive dominated in Russia. An individual, his rights and freedoms, his personal interests and problems were perceived, at best, as a means of, and, at worst, as an obstacle to strengthening the state’s power.”

Like his predecessors, Medvedev appealed to a “thousand-year history” to legitimatize his most difficult and important decisions. In his 2008 address, speaking about society’s “understanding” of the government’s move towards war with Georgia and the first phase of the economic crisis he concluded: “It could not be otherwise with a people with a thousand-year history who mastered and civilized a huge territory… created a unique culture and a powerful economic and military potential.” Medvedev’s statement is remarkably reminiscent of Putin’s phrase about “maintaining the state in the extensive space” quoted above.

Medvedev sought to legitimatize his political course by comparing it to the (recent) past. In 2009, he presented a modernization policy as “the first in Russia’s historical experience of modernization based on the values and institutions of democracy.” In this context the main point of reference was Soviet modernization, which Medvedev assessed positively: “at the expense of enormous effort an agrarian, practically illiterate country turned into one of the most influential industrial powers of the time.” On the other hand, Medvedev criticized it for being incomplete: “in conditions of a closed society and a totalitarian political regime, these positions could not be preserved.”

Medvedev made the same argument earlier in Russia, Forward!, in which he discusses not only the Soviet experience, but also the modernization course set by Peter the Great. Remarkably, the experience of the 2000s also became a matter of mild criticism: proclaiming the government’s modernization policy in September 2009, Medvedev stated that the results of the previous policy were not satisfactory, as the decisions “only reproduced the current model without developing it. They do not change the established order of life. They preserve the wrong habits.” Thus, justifying current policy by contrasting the present to the past may be considered a stable element of policy statements by all Russian presidents.

LACK OF HISTORICAL NARRATIVE

The collective past is used in presidential addresses to both firmly establish the present political course in the national tradition and to justify it through a critical reassessment of previous experience. The critique is aimed mostly at concrete events and processes in the recent past, whereas positive references to history are mostly of a general character and concern “centuries-long people’s traditions,” “Russia’s thousand years of history,” “our great culture,” etc.

The lack of a symbolic repertoire in presidential addresses is partly explained by a mismatch between the idea about the past that dominated the minds of the elite and the public consciousness, and the present tasks of symbolic politics. As Vyacheslav Morozov aptly noted, in the early 1990s Russia did not have a “historical narrative that would work as an alternative to the imperial narrative and could provide a basis for its self-identification as a nation state.” The situation has not changed much since then: it is no accident that the public does not typically have a favorable view of past events. A survey by the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Sociology in 2007 reveals that the number of historical figures and historical events that stir pride in Russians is extremely limited. Only four items from the list received the support of more than half of the respondents: 67 percent said that they are proud of the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II; 61 percent are pleased with the postwar restoration of the country’s economy; 56 percent take pride in great Russian poets, writers, and composers; and 54 percent are happy with the success of the Soviet space industry. These figures are indicative of the deficiency of the official symbolic policy which follows public perceptions of meaningful elements of the collective past, instead of creating new perspectives for interpreting the collective past, present, and future.

Of course the development of narrative(s) of a national past is primarily the task of professional historians. But the political elite should also do its part by introducing symbols of the past in the public discourse and taking part in reinterpreting them. It is clear that developing a symbolic repertoire to positively assess the national past was not a priority for those who prepared the annual presidential addresses. Although the speechwriters were aware of the significance of publicly using the past as a rhetorical method of dealing with history, they obviously preferred to confine themselves to those symbols of the national past that seemed undisputable. Yet the list of symbols is quite short for a transforming society with a long experience of an “unpredictable past.” Why the ruling class has avoided an official evaluation of the disputed issues is a subject for a separate, more detailed analysis of post-Soviet symbolic politics.

Such an approach to using the past for political pursuits has at least two empirically evident implications. First, in criticizing the past and refusing to expand the inventory to reassess the problem pages of national history, the ruling elite actually reproduces the cultural algorithm of “the break with tradition,” which has been typical of Russia since the 18th century. Second, there is a limited inventory of historical symbols available that could work as pillars for a positive national identity. Therefore the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II becomes the central historical symbol that is loaded (and overloaded) with new meanings.