For citation, please use:

Pakhalyuk, K.A., 2022. Actualized History of Old Russian Cities: International and Transnational Perspectives. Russia in Global Affairs, 20(4), pp. 181-209. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2022-20-4-181-209

Acknowledgements: The author thanks I. N. Grebenkin (Ryazan), D. Yu. Astashkin (Veliky Novgorod), G. V. Bakus (Tver), M. D. Kerbikov (Yaroslavl), and anonymous reviewers for their recommendations during the work on the article.

If the official memory politics revolves around the concept of the continuous 1000-year-long history of Russia, how does this affect the work with the past in regions that can objectively serve as the exponents of this “Russian antiquity?” This question became a starting point in studying (including field trips in 2020-2022, expert interviews, analysis of press materials and official documents) the historical identity of a number of regional cities in Central Russia, founded no later than the middle of the 16th century, such as Pskov, Veliky Novgorod, Vologda, Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Vladimir, Suzdal, Smolensk, Ryazan, Tver, Kaluga, Tula, and Bryansk (in other words, the acceptance/rejection criteria was the formation of the centralized state of Moscow). Note that the point at issue is not a “community of old Russian cities.” On the contrary, objective antiquity makes them basically comparable, including in terms of the practice of actualizing the past.

In the late 2000s, Russia stepped up its official memory politics, which turned history into one of the key value instruments of Russian politics. This period in the regions studied was marked by a significant shift in the institutionalization and expansion of practices used for working with the past. Consolidation of collectively shared historical visions is the result of efforts by an intricate network of state, public, and commercial organizations. Most of the museums, monuments, and historical and memorial spaces were created/organized during that period, which means that significant layers of history have only now become open to the public. Conflicting, contradictory, and tragic chapters have been pushed aside (or are absent altogether) as they are either uninteresting or considered dangerous. Quantitative changes sometimes surpass qualitative, that is, meaningful ones. Judging from museum exhibits, the most serious lacunae are found almost everywhere in the Soviet era, which partly explains obvious difficulties for consistent interpretation of the entire history. But this does not override the main point: local cultural elites are learning arduously to convey to the general public the chapters of the past that epitomize the agency of local communities.

Regional memory spaces are woven through the interaction of local and national plots, but also include numerous references to the international space. The latter is the subject of our study. We will leave the actual analysis of the formation of regional historical identities and their connection with the all-Russian one for other publications. Instead we will focus on identifying symbolic forms that are involved in the work with regional history, which entails a reference to the outside world. Culturologist Lyudmila Parts, when working with a different set of material, noted that it was appropriate to study the binary “capital-province” discourse together with a third component—external Other (West/Europe), which is often portrayed as dangerous [Parts, 2022]. The material we have studied does not deny the existence of such approaches, but it allows us to argue that the outside world can simultaneously appear as both something hostile and as a space of cooperation. It is wrong both to think that this division is due to the difference between state and non-state actors, and to make assumptions that the perception of “Russian antiquity” is reduced to Orthodox and militaristic content. International space becomes the subject of work by those who, as a rule, are neither academically nor professionally connected with this sphere. Their perception of the past influences the public understanding of world politics, since they offer estimates and set the basic coordinate system (social ontology). One cannot but notice a certain (not complete yet) parallel: while the science of international relations already acknowledges the presence of not only the state but also of numerous other significant actors in the global arena, regional museums are only learning not to reduce the international space to interstate interaction.

One of the key methodological difficulties is that we have to deal not with integral narratives, but with numerous citations and disguised references integrated into museum exhibitions and urban spaces. We use the expression “reference to the international space” deliberately because we are not going to talk about the outside world in earnest. So, during the analysis, we must outline the fragmentation of these references and, instead of generalizing them, find common logic behind them. This is why we accorded priority to specific semantic contexts, which for some reason led us to refer to the international space. Moving from the general to the particular, we will first consider its place in the most significant historical plots (the “golden era” myth) and common ones (military history), and then present a wider array of references revealing the readiness of actors engaged in memory politics to view the outside world as something more than just a source of threats.

THE GOLDEN AGE MYTH AND THE INTERNATIONAL DIMENSION

The founder of structuralism, Ferdinand de Saussure argued that significance is determined by the position of the sign in the general structure, and not by specific content. The actualized history of most of the studied cities contains a myth—conditionally—of the “golden era,” when a certain period of the past becomes the subject of special glorification and attention as the expresser of local identity. This symbolic construct is explicated in museum displays and newfangled monuments, drawing on the works of historians and supported by preserved/recreated cultural heritage sites. We will leave a detailed study of such myths for another occasion and will focus instead on how the international dimension weaves into them.

In almost all cases, it appears in the form of an external enemy, the description of the struggle against which is designed to cement together local and national plots. However, in Veliky Novgorod, the “golden era” myth also opens up a transnational dimension, and the glorification of medieval princes in Tver and Ryazan results in the emergence of a “second external enemy”—Moscow. In some cities (Tula, Smolensk, and Pskov), the construction of historical identity through the “shield of Russia/Moscow” metaphor, which implies the struggle against a permanent external threat, intertwines national and local history even tighter, depriving the latter of integrity and self-sufficiency. However, as Tula’s experience shows, in the late 2010 and early 2020s, local cultural elites, on the contrary, succeeded in overcoming this problem.

In Vologda, Yaroslavl, and Kostroma,” the “golden era” myth was tied to the 17th century—the heyday of trade with Europe through Arkhangelsk, which, however, is not reflected in any significant way in the historical and memorial space. In Vologda, the museum of Peter the Great, opened in 1875, is just a weak reminder of those ties. The emperor often stayed in this stone house, owned by a Dutch merchant, at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th centuries. The irony is that the memory of those events is embedded in an object of cultural heritage, which was created by a foreigner and which was subsequently turned into a museum in order to glorify the emperor, who destroyed transit trade and, consequently, all prospects for the city’s development.

On the contrary, in Yaroslavl and Kostroma, the state and the Russian Orthodox Church actualize the topic of confrontation with an external enemy—the Poles. The former focuses on the Second People’s Militia, which headed to Moscow from here in 1612 (this gives reason to present the city as one of the capitals); the latter emphasizes the salvation of Mikhail Romanov (the image of Ivan Susanin). In Vladimir, the “golden era” is the Vladimir-Suzdal Principality. Its decline is also associated with an external threat—the storming of the city in 1238 by Mongol troops. That battle is depicted in a large-scale diorama (created in 1974) in the military-historical museum housed in the Golden Gate, where one of the exhibits directly links the defense of all Russia, including Vladimir, with the salvation of Europe from the invaders: “Russian people, including Vladimir residents, put up courageous resistance to the invaders <… > Having taken the main blow from the invaders, Russian people saved European civilization from death and destruction.” This is a rare case for regional museums, when the struggle against one external threat is explicitly portrayed as a boon for another part of the world.

Peter the Great’s house in Vologda, 2020

In Ryazan and Tver, owing to the regional authorities and the Russian Orthodox Church, the “golden era” is tied to the rule of two grand dukes, Oleg and Mikhail, respectively. In both cases, this actualizes the memory of the struggle not only with the Mongol/Golden Horde conquerors, but also with Moscow. In Ryazan, this contradiction is associated with Grand Duke Oleg on the eve of the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, when he was guided by the interests of his own principality. The museum exhibition “overcomes” this quandary by highlighting the figure of Peresvet (one of the heroes who fought with a Mongolian warrior on the eve of the battle). The central showcase features what is claimed to be his staff, but the explication (as of 2020) does not indicate in any way that the exhibit has been mythologized. In 2016, a monument to Sergius of Radonezh was unveiled in the park near the Ryazan Kremlin. He is known for having “reconciled” Dmitry Donskoy and Oleg of Ryazan, who accepted political subordination to the Moscow ruler.

In Tver, an integral part of the myth about Prince Mikhail is his victory in the Battle of Bortenev in 1317, which is portrayed, mainly in popular literature, as the first victory over the Golden Horde. It is even mentioned on one of the bas-reliefs on the stele in the City of Military Glory, which says that his troops defeated the “adversaries of Tver.” The evasive wording is due to the fact that it was the Moscow troops who suffered the defeat, while it remains unclear how much the Tatar detachment was actually involved in that battle [Borisov 2018, p. 258]. This deformed border between the two “external” enemies simultaneously indicates both the resistance of the historical material itself and the presence of certain anti-Moscow and regionalist sentiments among the Tver cultural elite. The image of Mikhail of Tver only intensifies the conflict along “the region-the center-the outside world” line.

Bas-relief of Mikhail of Tver on the stele “The City of Military Glory” in Tver, 2020

The international dimension weaves into the historical identity of Veliky Novgorod in a more complicated way. It is the period of the 11th-15th centuries, ending with the violent accession of the Novgorod Republic to the Grand Principality of Moscow, which is claimed to be the heyday here. The history of the city from the mid-17th century has been almost completely excluded from museum expositions. With all visual objectivity, Veliky Novgorod today is a vivid embodiment of the greatness of medieval Russia, but its history gets controversial when it comes to political independence and confrontation with Moscow, a narrative that is quite convenient for feeding regionalist and anti-federal rhetoric.

This is probably why the “golden era” has been legitimized through the glorification of Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky as part of the national historical narrative. Two monuments to him were built in 1985 and 1995. In the historical museum, subordinated to the federal Ministry of Culture, his activities are presented in an anti-Western way. For example, one of the explications says quite clearly: “In the difficult years of the Tatar-Mongol invasion, Novgorod had to repel the onslaught of German and Swedish feudal lords. In 1240, the Novgorodians, led by Alexander Nevsky, inflicted a crushing blow upon the Swedish conquerors on the banks of the Neva <… > on April 5, 1242, the famous Battle on the Ice took place, which brought the Novgorodians victory over the Teutonic dog knights” (trip, August 2021).

On the other hand, it is difficult to advance the “golden era” myth without clarifying the chapters of history that connected the city with Europe, which opens up a transnational perspective. If it remained just in the chronicles and works of historians, the authorities could eagerly limit it to purely academic discussions, but this is somewhat difficult to do. In fact, some of the pieces of jewelry exhibited in the Episcopal Chamber of the Veliky Novgorod Kremlin (15th century) were made abroad: they are intended to tell of the city’s prosperity, but inevitably reveal close trade ties. Cultural contacts are also embodied in stone: for example, elements of Gothic architecture are found in the Church of Theodore Stratilates on the Brook, and even more so in the Episcopal Chamber. All this is reflected in explications and tour programs, thus presenting Russian antiquity in conjunction with not only the Byzantine, but also Western cultural traditions.

Church of Theodore Stratilates on the Brook in Veliky Novgorod, 2021

In the 1990s, the “golden era” narrative was furthered by updating the history of ties with the Hanseatic League. Traditionally, Novgorod is portrayed as a member (in fact, one of the largest affiliated cities) of this network trading organization, which controlled a significant part of Baltic trade in the 13th-16th centuries. In 1980, the Hanseatic League of Modern Times, an international inter-municipal organization of former member cities, was founded. Veliky Novgorod was the first Russian city to join it in 1993. This “invented European tradition” made it possible to attract both tourists and additional funding for the development of historical infrastructure. In 1994-1999, this organization co-funded the restoration of the second ancient church in the city—St. Nicholas Cathedral (1113) known for its unique mid-12th century frescoes, in fact, one of the oldest authentic images of the Last Judgment ever found in Russia (Razina, 2017, p. 3). In 2009, the city hosted the XXIX International Hanseatic Days (a major cultural and economic festival). In honor of this event, a Hanseatic Sign—a monument in the form of two ships and a large fountain inlaid with the coats of arms of the sixteen member countries—was unveiled in the historical center of the city, in the Yaroslav courtyard, near the medieval German courtyard. Not far from it, there is a small eatery called Hansa, located on the grounds of the Truvor Hotel (but it makes no effort to imitate the names of German or Baltic dishes, let alone cuisine itself). Actually, the Hanseatic theme is important for positioning the city in the international arena through participation in Hanseatic events, student exchange programs, and exhibition projects (in 2015, Hansemuseum was inaugurated in Lübeck, having received twenty-five items from the Novgorod Museum-Reserve; in 2019, a thematic exhibition titled “Novgorod and Hanse: A Window to Europe” opened in Veliky Novgorod) (Novgorod and Hanse, 2019).

Neighboring Pskov looks completely different as it tries to construct its historical identity through both the “golden era” myth (incorporating not only a veche republic, but also the 16th-17th centuries) and the image of the region as the “northwestern shield of Russia.” This is the result of close cooperation, started in the 1990s, between the official authorities and the Pskov diocese. The “golden era” myth is based on a rich architectural heritage and developed further in exhibitions, including the latest ones telling of the Voivodeship of Ordin-Nashchokin and the Merchant Postnikovs’ Chambers. The image of the “northwestern shield” is projected primarily in the rhetoric of officials, journalists, and teachers, but it is not so manifest either in urban spaces or museums. Rather, there are just separate elements: the glorification of Prince Dovmont (13th century), place names, Orthodox tradition, coat of arms and individual events; the urban legend has it that part of the collapsed external fortifications in the city is the breach made during the siege by Stephen Báthory’s Polish troops; and there are also some monuments related to the Great Patriotic War and Nazi crimes. All this de-actualizes the transnational perspective, although historically there are probably just as many grounds for it as there are in Veliky Novgorod. In fact, the city is a member of the Hanseatic League of Modern Times and hosted a major international festival in 2019, but the importance of this topic is obviously toned down both in museums and urban spaces.

Just like neighboring Novgorod, Pskov is merging the regional and national historical agendas—not without the federal center’s help—by appealing to the image of Alexander Nevsky and glorifying his victory over the external enemy (Teutonic crusaders) in the Battle on the Ice. Big monuments to the grand duke and his troops were unveiled on Mt. Sokolich near Pskov in 1993, and on the shore of Lake Peipus in 2021. Not far from the latter, the Museum of the Battle on the Ice (initially municipal, then private) was opened in the village of Samolva in 2012. Its founder Vladimir Potresov is convinced that it was one of the key battles of its time, giving the memory of it an anti-Western and Orthodox tint (Battle on the Ice, 2018). The problem is how to link the prince to urban history in a more consistent way. After all, he was from Novgorod, not the local ruler. In 2021, the Pskov Kremlin hosted a temporary exhibition as part of federal events dedicated to the 800th anniversary of the birth of Alexander Nevsky. About a dozen stands told the story of his life and glorification, but the city’s history proper included just references to the participation of the Pskovites in the Battle on the Ice or a review of place names in Pskov.

The situation is even more complicated in Smolensk, which is the only city being reviewed that for a long time (in 1395-1514 and 1611-1654) was part of another state—Grand Duchy of Lithuania and then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The history of the Principality of Smolensk could potentially become the “golden era,” but it is updated publicly only in the Historical Museum (of regional subordination). The image of the self-sufficient Principality of Smolensk is viewed by some statists as a threat of separatism or connivance at otherwise unpopular ideas that Smolensk was originally Belarusian territory. A review of a regional history textbook, released in 2016 by the federal executive directorate of the Russian Military Historical Society, is quite indicative: “The version of Russia’s medieval history presented in the textbook aims to form such a variant of regional identity that would make Smolensk residents associate the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with their ‘historical ancestral homeland’ and identify the Smolensk region with ‘Belarusian lands’ captured by people from Muscovy, thereby denying the latter (notorious ‘Muscovites’) the right to be considered Russian people” (Kononov, 2016) This review was posted on the personal website of Vladislav Kononov, who was the director of the regional Department of Culture and Tourism in 2013-2014.

The Polish period of history is also quite controversial. On the one hand, the exhibition in the Historical Museum offers a detailed account of that time and of the successful integration of the Polish nobility into the Russian elite. The memory of this period is embedded in urban space by way of cultural monuments and urban mythology: in the historical center of the city there is the earthen Royal Bastion built by the Poles. A plaque in three languages—Russian, English, and Polish—installed in the early 2010s tells about its history. Interestingly, the city clock is generally seen as the one that was on the city hall in the 17th century. One can find this story even in the guide written by abovementioned Vladislav Kononov, in a section with the telling name “Echoes of the Polish Era.” The truth is that the existing clock was built in the 19th century in place of the old one. But severed tradition and the lack of physical continuity are not an obstacle to actualizing spatial and essentially imagined continuity.

On the other hand, the authorities build Smolensk’s urban identity using the image of the “western shield of Russia” and integrating the struggle against the Poles (1609-1611), the French (1812), and the Germans (1941-1944). The first two military events are directly related to the main actualized landmark of the city—the Smolensk Fortress wall. The monument to the soldiers, defenders and liberators of Smolensk unveiled in Victory Square in 2015 became an outspoken visualization of this continuity. It clearly refers to these “three feats of arms” through the figures of soldiers and bas-reliefs with inscriptions. Back in 1987, the military-historical museum, housed in one of the towers of the Smolensk Fortress wall, received the symbolic name “Smolensk Is the Shield of Russia.”

The image of the shield is developed through military-historical exhibitions portraying the Poles and the Germans as the main enemies. One room in the Historical Museum is devoted almost entirely to the defense of 1609-1611 (the battles fought for the city in 1812 blend into the general history of that war). This topic also opens a new exhibition (unveiled in 2018) at the Katyn War Memorial (its scientific concept was developed by the State Central Museum of Modern History of Russia and the Russian Military Historical Society). It is devoted to contradictory, but as its organizers claim generally positive, Russian-Polish relations in the 20th century. We think that the introductory reference to the 17th century is an attempt to remind visitors that the Poles were historical enemies on this land. Updated in 2015, an exhibition titled “Smolensk during the Great Patriotic War” has a whole room of exhibits offering a detailed account of the Nazi occupation and victims of Nazi terror (including Jews and Gypsies). In none of the other cities studied, museums provide such an insight into this topic.

The neighboring Bryansk region was also part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania for about 150 years from the middle of the 14th century, but this period is represented by only a small stand in the general exhibition of the Bryansk Museum of Local Lore (of regional subordination). The “golden era” myth unfolds around Soviet history, which is closely connected with the Great Patriotic War and the struggle against the German invaders. In the 2000s-2010s, the city administration, with the support of local businesses, created two museum and memorial complexes outside the city: one is called Partisans’ Clearing in the Woods (heroic glory) and the other one is Hatsun (the tragedy of the civilian population).

The latter is dedicated to the destruction of the Russian village of the same name during a Nazi punitive raid. What makes it so important for our study is that the Bryansk region is not the only territory that suffered from the Nazi occupation policy, but it is the only one that by the beginning of the 2010s had created such a big memorial dedicated to the tragedy of the civilian population. However, the memorial does not feature a clearly defined image of the enemy. Instead, its central element is a film made of pre-war photographs of villagers, which is played above the showcase displaying a machinegun belt found at the scene of the execution. In other words, the organizers tried to show the peaceful life of ordinary people, which was destroyed by the Nazi.

Just like Smolensk, Tula developed its historical identity for decades partly as the “southern shield of Moscow” by making references to the Battle of Kulikovo (in 1996, the federal museum “Kulikovo Field” was created in the region), the foundation of the Tula Kremlin (thematically connected with defense against Crimean Tatar raids in the 16th-17th centuries; in 2015, a monument to Dmitry Donskoy was also unveiled there), as well as to the defense in 1941. However, the way of handling these plots is different: their development by local cultural elites contributes to exploring unknown chapters in the history of the city itself. For example, archaeological excavations conducted on the Kulikovo Field since the 1980s helped create a local archaeological school and discover the previously unknown medieval history of the region. In the 2010s, the reconstruction of the Kremlin led, among other things, to an exhibition based on archaeological data and devoted to the original history of people who lived in Tula in the 16th-17th centuries. Even in the Tula Defense Museum, opened at the end of 2021 in the local Patriot Park (funded by the federal Ministry of Defense), the exhibition is arranged in such a way as to show the fighting urban community, in all its diversity, rather than individual battles in a particular territory.

MILITARY HISTORY AND THE PROBLEMATIC IMAGE OF THE ENEMY

Most often, the “international” appears in museums, urban spaces and the media when military topics are addressed. Stories of fighting an external enemy, in or outside a certain region, have turned into a key mechanism that tightly links national and regional historical aspects, blurring the borders between them. Military-historical exhibitions in regional museums are organized according to this principle. Some cities have their own military-historical museums (Kostroma, Ryazan, Vladimir, Tula), where the continuity of eras is achieved through a mechanistic fusion of completely different episodes from the military past and the participation of local residents in them. Private museums of weapons (Yaroslavl, Ryazan) and military glory (Tver) follow the same logic.

Fragment of the exposition “Four Eras of Military Glory” in Tver, 2020

In the studied mesoregion, of all wars, the Great Patriotic War, the Time of Troubles (confronting Poles and partly the Swedes—Vladimir, Kaluga, Smolensk, Veliky Novgorod, Pskov, Kaluga, Yaroslavl, Tver, Kostroma), and the period of Mongol domination (Tver, Ryazan, Vladimir, Tula, Kaluga region) are present most graphically in public space. Imperial period wars—Northern War, Napoleonic Wars, Crimean War, World War I, less often Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878, and the Russian-Japanese War of 1904-1905—are mentioned only in exhibitions or rare monuments, and for this reason they can hardly produce a vivid image of the enemy. Smolensk is indicative in this respect. The Napoleon invasion is associated with the devastating occupation of the city and the destruction of a number of towers in the Smolensk Fortress. However, there are no persistent negative images of the enemy army as evidenced by wide public attention to the Russian-French search activities and archaeological excavations in 2019-2021, after which more than 120 soldiers of the Russian and French armies of 1812 were reburied in Vyazma, and the discovered body of General Charles Etienne Guden was solemnly handed over for burial in Paris (Teller Report, 2021). It is impossible to imagine anything like this with regard to any of the WWII German generals.

Moreover, excessive exploitation of the enemy theme can present difficulties when “its descendants” are members of the modern Russian nation. In particular, throughout the 2010s, the Kaluga regional administration repeatedly urged the federal authorities to include November 11 in the official list of days of military glory and memorable dates in Russia (approved by Federal Law No. 32) as Victory Day in the “Great Stand on the Ugra River.” This question was considered in the State Duma in 2019 (Shulepova, 2019), but the Kaluga authorities’ request was turned down due to the opposition from Tatarstan. However the struggle for the list of official commemorative dates pursued pragmatic purposes as well: Kaluga needed additional arguments in order to attract federal funding for historical and tourist projects. So, November 11 has been a memorable date in the Kaluga region since 2017, and in 2019, the village of Dvortsy was officially designated as the “Frontier of Military Glory,” and as such it hosts the cultural and historical festival UgraFest (RVIO, 2020).

Fragment of the exposition “Marshal of Victory Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov” at the Military Historical Center in Kaluga, 2021

Using the theme of external threat does not mean creating a vivid and expanded image of the enemy. Its presentation, mainly through references, items of weaponry and uniform, makes the image faded, abstract and imaginary. The further the era in time, the easier museums make comparative stories about the warring armies. Perhaps the main exception is the interactive exhibition “Four Eras of Military Glory,” opened in Tver in 2017 at the local branch of the Union of Paratroopers of Russia. Serving the purpose of patriotic education, it offers a series of warrior mannequins from different eras, clad in battledress and armed with weapons. It shows Russian soldiers along with their adversaries, including from the WWII period. This approach is intended to place emphasis on clarifying combat tactics of different eras. One of the authors of the exhibition, who took me on a tour (in the summer of 2020), stressed that young people attending the museum are taught to understand the need to know the enemy. In other museums, such structural juxtaposition of opponents may be part of the display, but not the main structural element. For example, in the Vladimir Historical Museum (exhibition of 2003), a visual narrative of the storming of the city in 1238 involves replicas of a Russian observation tower and a Mongolian wagon. Mannequins of both Swedish and Russian soldiers and officers stand in the Alekseevskaya Tower of the Novgorod Kremlin (exhibition of 2020), where one can learn about the fortress garrison, its assault by Swedish troops in 1611, and the subsequent occupation.

The images of the Soviet Union’s opponents during the Great Patriotic War are also quite telling. On the one hand, they are present in the museums of Smolensk, Bryansk, Veliky Novgorod, and Yaroslavl (Museum of Military Glory) that tell of the suffering endured by civilians. On the other hand, only two places offer actual visualization of that time. In Kaluga’s Museum “Marshal of Victory Georgy Zhukov” (opened in 2020), where a significant part of the exhibition uses “live” scenery, the story of the battles for Berlin is accompanied by graphic images of Germans behaving differently in the besieged city—most are fiercely fighting, residents are trying to run away, and one officer is changing into civilian clothes.

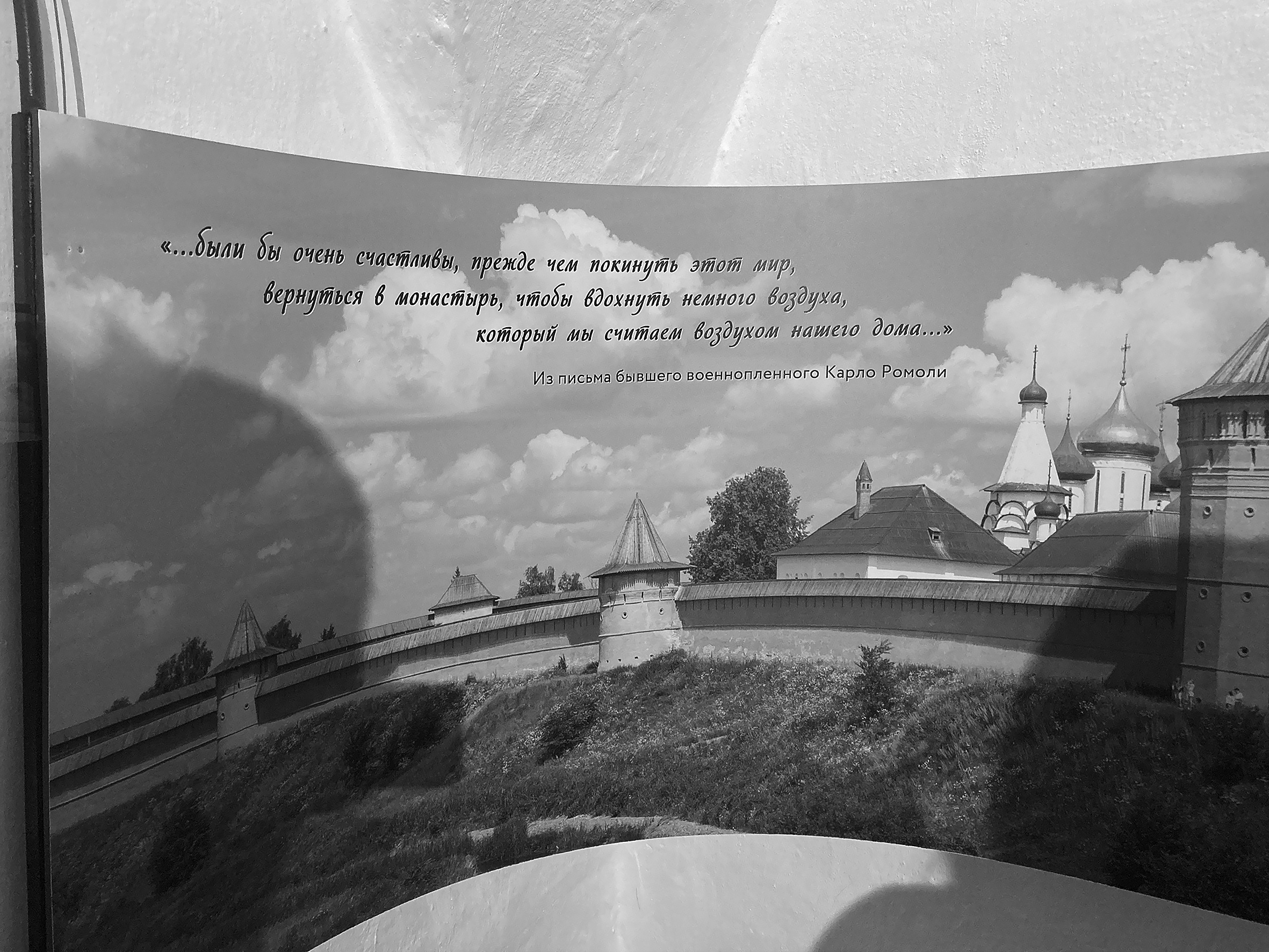

The Savior-Euthymius Monastery in Suzdal (part of the federal Vladimir-Suzdal Museum-Reserve) is completely different. The exhibition “Suzdal Prison. The Chronicle of Two Centuries of History” (2001) is built as the history of a place that for a long time was used as a penitentiary. This explains why different groups of prisoners are brought together, including those who were persecuted for political reasons in imperial and Soviet times. These include the Czechoslovak military led by L. Svoboda, who were interned at the beginning of World War II, and who fought together with the Red Army already in 1941. A separate stand tells about their accommodation in the former monastery and further joint heroic struggle. An uninformed visitor will need to make some effort in order to understand this unexpected transition: the condemnation of political repression is suddenly interrupted by a heroic story, which, in our opinion, once again emphasizes the contradictory and nonlinear nature of history. Later the monastery was used to accommodate prisoners of war from Germany and its allies. Several stands focus on controversial aspects of their life, help and attention from local residents, and the story ends with a demonstration of joint commemorative events held in the 1990s, emphasizing how deadly enemies begin to interact, and humanity makes it possible to overcome understandable alienation.

Fragment of the exposition “Intertwining Fates” in Suzdal, 2022

The fate of Italian prisoners of war is shown in more detail in an exhibition titled “Intertwining Fates” (2003, reopened in 2021). The first part turns to their personal experience of being in captivity, accentuating fairly good contacts with local residents, and the prisoners’ perception of the city’s cultural heritage. As in the previous exhibition, humanism and ancient culture become the threads that stitch up the wounds of war. The second part is dedicated to Andrei Tarkovsky, who filmed his Andrei Rublev by the monastery walls. This circumstance is necessary for making the transition to the figure of his friend, Italian artist and screenwriter Tonino Guerra. Having visited Suzdal and learned about the fate of Italian prisoners, he donated some of his works, including those dedicated to the city, for this exhibition. It features a whole array of images and human connections that unfold in time around ancient Suzdal as a bearer of Russian antiquity.

The existing institution of twinning between Russian and foreign cities in the reviewed regional capitals did not manifest its role in terms of actualized history. However, we found two symptomatic cases when, in the 2010s, amid the increasing glorification of the Great Patriotic War, separate projects related to the topic of Russian-German reconciliation were carried out, with twinning arrangements making it possible to implement and publicly legitimize them. For example, in the early 2010s, cooperation between Russia’s Vladimir and Germany’s Erlangen was epitomized by the planting of the Oak of Friendship in Victory Square in 2011, the installation of a memorial sign, and meetings of Red Army and Wehrmacht veterans (Bez formata, 2016). In 2021, Veliky Novgorod hosted an exhibition that featured war-time images of the city, drawn by two artists who had fought there against each other during the war, G. Gruner and S. Pustovoitov.

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE ENEMY IMAGE

In existing symbolic spaces, both the “golden era” myths and the military past tend to present the outside world as a source of threat. This is, indeed, a significant, but not the only meaningful context for the emergence of the international dimension. If we take a step aside from the dominant historical plots towards a consistent study of all existing museums and symbolic spaces as such, we will find a number of other methods to correlate local, national, and international histories.

The first method, found in the state museums of Vologda, Kaluga, and Ryazan, suggests that the reference to the international dimention serves the main task—to emphasize the international significance of the presented events. The Ryazan Museum of the History of Airborne Troops is indicative in this respect (the current exhibition on display since 2018, subordinated to the Central Museum of the Armed Forces of Russia). In the beginning, the exhibition tells about the development of skydiving abroad (16th-19th centuries) (which largely gave rise to our Russian tradition), and the latest sections are devoted to international military cooperation, including the participation of Russian paratroopers in UN missions, featuring dozens of stands with military uniforms of friendly armies. A similar logic can be seen in the Ryazan Museum of Travelers (2012, municipal), which has summarized information about tourists, even remotely connected with Ryazan, and dedicated one of the exhibitions to “Russian America” (based on researcher M. Malakhov’s personal collection).

Fragment of the exposition at the Museum of the History of Cosmonautics in Kaluga, 2021

Similarly, one of the key museums in Vologda—the Museum of Lace (of regional subordination, opened in 2010)—narrates the history of this type of textile industry by reminding the visitors that lace as such first appeared in early modern Italy and was brought to Vologda at the beginning of the 19th century by one of the landladies. Thus, what is perceived as something ultimately Russian, in reality—and the exhibition makes no secret of it—was borrowed and elitist, but adopted in Russia and took root in folk culture.

The fourth example is the State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics in Kaluga, subordinated to the federal Ministry of Culture. The old exhibition was opened in 1967, but at the end of April 2021, a new building was added to house a large-scale multimedia area that breathes a complteley new meaning into the museum. While in the “old” building, the world history of space exploration focuses laregly on the development of rocket and space thought in Russia and the USSR, in the “new” building, the latest Russian space achievements are literally woven into the history of international space cooperation and a number of foreign space programs. The promoted idea of Russia’s leadership in this area does not seek to hush up other nations’ merits. The new exhibition can hardly be called consistent or linear-narrative: it is designed to stir emotions and immerse the visitors in a world of cosmic exotics, and therefore is open to multiple interpretations. The thematic connection with the house-museum of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and the relatively new museum of Alexander Chizhevsky reveals a combination of local, national, and global narratives in the city’s historical and memorial space.

Local cultural and political elites’ efforts to include cultural heritage sites in UNESCO’s World Heritage List are underlain by the same cultural logic. This is a multi-stage process and even before a site is shortlisted, it has to be approved by a number of agencies, including the federal Ministry of Culture and structures related to the Russian Foreign Ministry. Of the nineteen Russian sites included in the World Heritage List by cultural rather than natural criteria, five are in the chosen interregion: Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings, White Monuments of Vladimir and Suzdal (both in 1992), Ensemble of the Ferapontov Monastery (2000), Historical Centre of the City of Yaroslavl (2005), and Churches of the Pskov School of Architecture (2019). All other Russian regions have also pushed for getting their cultural monuments included in this list. At the beginning of 2021, Smolensk proposed the city fortress as a candidate, and the director of the Smolensk Fortress federal museum, S. Pilyak, (2021, p. 19) argued that the fortress’ military past could justify its universal value. The willingness to combine the incompatible (the military-nationalist image of a “shield” and cultural universalism) appears to be a characteristic feature of a certain part of regional culture managers and their way of thinking.

Commemorative crossstone in memory of the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide. Veliky Novgorod, 2021

Some private museums in Tula, Tver, and Ryazan use the second method of appealing to the international space—placing local history in a transnational perspective (the actualization of the Hanseatic topic in Veliky Novgorod mentioned above falls into the same category). The fundamental difference in terms of how the exposition is arranged and material presented is in the visualization of connections between the local and international dimensions, with the “intermediate” national level playing just a minor role. These connections are numerous and not always expected, but direct and logically defined.

The Goat Museum (2008) in Tver is based on the ethnographic facts concerning the development of Saffiano leather production in Tver in the 17th century, specifically the processing of goat hide for Saffiano leather boots. The exhibition occupying several rooms presents a series of goat images (figurines, paintings, sculptures, names, etc.) from around the world. The interactive Museum of the History of Ryazan Lollipop (2017) is arranged in a similar way. It mentions the sugar factory founded in the 19th century by N.P. Shishkov. The main rooms are dedicated to the personality of the owner and his participation in the Patriotic War of 1812. His office and the interior of the village hut, where sugar and lollipops were made, have been reconstructed. However, this local story is inserted not into the national context, that is, Russian sugar industry, but into the transnational one. The exhibition begins with Alexander the Great, who allegedly was the first European to have tried this product, and Christopher Columbus, because sugar cane was cultivated in the American continent he discovered. Showcases contain reconstructed household items of American Indians. In Tula, a private multimedia Machine Tool Museum was opened in 2019. It tells the history of industry in Russia, including the Tula region, through a network of transnational technological innovations, borrowings, explorations, own inventions, and erroneous solutions. Let us also pay some attention to the historical salon “Aroma of Times” (2019, guide K. Panacheva’s project) devoted to everyday culture, primarily perfume, in Ryazan in the 19th-20th centuries. The exhibition refers to the first perfume store opened in the city by Maximilian Faktorovich, who subsequently became known as Max Faktor after his emigration to the United States. This cosmetics brand is quite famous in Russia thanks to advertising.

The third method dates back to the Soviet era, when the officially imposed idea of the “friendship of peoples” made it possible for museums to display certain “foreign” local plots. At the end of the Soviet era, Yaroslavl began to create a memorial museum of Belarusian poet M. Bogdanovich, who had spent part of his youth in this city. The story of his life and family is complemented with his contribution to Belarusian poetry and longing for his native places. Since 1995, this memorial museum has been officially called the Belarusian Culture Center. Of the Soviet-era monuments, it is worth paying attention to those of them which were legitimized by the Soviet ideological system that glorified both Marxism (monuments to Karl Mars in Tver, Tula, Kaluga, and Yaroslavl) and brotherhood in arms (in Ryazan, it is the Polish 1st Infantry Division named after Tadeusz Kosciuszko).

The fourth method of appealing to the international space implies a blurred border between the “foreign/non-ethnic” and is the result of the local diasporas’ intention to identify themselves in a symbolic space. A monument to Russian-Armenian friendship was unveiled in Vologda opposite the Drama Theater in 2012 (a tribute to the contribution of Armenian businessmen to the city’s economy); a similar cross was found in Pskov near the Church of Alexander Nevsky (installed in 2003). In 2015, the Armenian community helped install a commemorative cross-stone (see the image) at the Khutyn Monastery near Veliky Novgorod in memory of the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide. However these initiatives are not central to urban memorial spaces. In 2015, the private Museum of Gypsy Culture and Life opened in Kostroma (this is also the only museum in Russia that tells about the genocide of Gypsies during the Second World War). In Kaluga, an exhibition dedicated to Imam Shamil (at the end of the Caucasian War he stayed there for about ten years in honorable captivity) was organized at the expense of the local Dagestani diaspora.

Fifth, the international dimension is localized most fully and vividly in a number of regional art galleries (they also have the status of “museums,” according to the generally accepted international terminology). In Tver, Yaroslavl, Ryazan, Kaluga, Tula, Vladimir, and Smolensk, they began to appear shortly after the 1917 Revolution, having absorbed private collections from the manor houses of the former nobility. This allows visitors to see the works of not only domestic classics, “canonical for Russian fine art” (Rokotov, Aivazovsky, Repin, Lentulov, Korovin, etc.), but also foreign masters of the 17th-early 20th centuries (and even world classics, such as Peter Rubens in the Kaluga Museum of Fine Arts).

THE INTERNATIONAL AND HISTORICAL RESPONSIBILITY

All the examples described above concerned situations where the international dimension fits smoothly enough into the prevailing historical narrative. Images of the enemy, historical and cultural ties, and symbols of external recognition—all this quite obviously contributes to the formation of a “positive image of oneself,” which is the main task of official historical policy. Things become completely different when it comes to responsibility for one’s own crimes against foreign citizens. In particular, one of the controversial chapters is the execution of Polish prisoners of war by the NKVD in the spring of 1940, when more than twenty thousand people were killed. These acts took place in different regions of the USSR, but two major executions were carried out outside Smolensk (near the villages of Kozyi Gory and Katyn) and Tver (near the village of Mednoye). In Soviet times, responsibility for the Katyn massacre was shifted to the Nazis (the execution in Mednoye was completely hushed up), but in 1988, the Soviet Union officially admitted its responsibility. In modern Russia, the State Duma adopted the relevant statement in 2010, and both Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev have repeatedly spoken on this topic, leaving no doubt about who exactly carried out the executions.

War Memorial in Katyn, 2021

In 2000, museums and memorials were opened in Katyn and Mednoye. The Katyn Memorial commemorates two different groups of people repressed during the Stalin era—Polish prisoners of war in 1940 (more than four thousand) and Soviet citizens (more than eight thousandii). Initially, the dominant motif was the memory of the Polish victims: a large memorial made of rusty (symbolizing the suffering) slabs; the entrance is framed by Polish military symbols, opposite the memorial cross are Catholic, Orthodox, Jewish, and Muslim signs (symbolizing the multitude of the victims). Also, at the entrance to the place of the execution of Soviet citizens, there is a red Orthodox cross and a freight car (used to transport prisoners) not far away. The memory of the repressed Soviet citizens was important both for the residents of Smolensk in general and for the Smolensk diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church in particular (Archbishop Seraphim of Smolensk and Dorogobuzh, now revered, was killed there).

Despite the unequivocal position of academic historical science, Katyn revisionism developed in Russia at the same time, denying the participation of the NKVD in the executions and considering the recognition by the Soviet authorities of responsibility for them as one of the factors that contributed to the collapse of the USSR. The denial of crimes turned out to be linked most closely to the imperial complex and nostalgia for the Soviet past. At first this did not affect the official memory politics in relation to Katyn and Mednoye, but serious changes started looming in the 2010s.

In 2012, the two memorials were put under the supervision of the Moscow-based State Central Museum of Modern Russia. A few years later, redevelopment started in Katyn in order to play down the murder of Poles not only by emphasizing third-party historical plots (containing direct accusations against Poles), but also by bringing up the tragedy of Soviet citizens. In 2017, a large monument was unveiled at the burial place of Soviet citizens, with federal politicians attending the ceremony. Two new exhibition spaces were commissioned at the same time. The first one is located at the entrance and dedicated to the Polish and Soviet victims of Stalin’s terror: political and ideological contexts, the reasons for the repression and those responsible remained behind the scenes (the absence of the image of the perpetrator fundamentally distinguishes this memorial from European “museums of memory”), and visitors are invited to take a closer look at individual tragedies relayed through photographs, personal belongings recovered from graves, and documents, including copies of rehabilitation certificates. The second exhibition space on the territory of the memorial is dedicated to the history of Soviet-Polish relations in the 20th century and deliberately emphasizes their positive aspects. Not far from the freight car, there is a permanent exhibition dedicated to the Soviet-Polish war of 1919-1921, and emphasizing the tragedy of Soviet prisoners of war. Earlier, it focused on the history of political repression in the Smolensk region.

Katyn. Cenotaph plate telling of the Soviet prisoners of war allegedly killed here, 2021

Not far from the entrance there is a plate installed back in the 1980s to mark the place where the Germans had allegedly shot more than 500 Soviet prisoners of war. There is no documentary evidence to prove this, and the plate was installed by the Soviet authorities in an attempt to blame their own crimes on the Nazis. The meaning of this plate in the memorial space is not substantiated in any way, while the guide (August 2021) describes it as a kind of cenotaph. In June 2021, a temporary exhibition dedicated to the Nazi terror in the Smolensk region was also opened here.

Consistent attempts to play down the topic of repression against Polish citizens by invoking Nazi crimes and the tragedy of Soviet prisoners of war, that is, unobtrusively compare (if not oppose) one tragedy to others, is probably motivated by the desire to convince visitors of its triviality and divert their attention from uncomfortable questions about its root causes and political responsibility, although the memorial itself is the embodiment of the latter. Ironically, the way this is done can, on the contrary, prompt visitors to compare the Stalinist USSR with Hitler’s Germany, and the lack of sufficient historical information will only push them towards making the most incredible conclusions.

The next stage in the exploration of the topic is associated with Tver, where two memorial plaques were dismantled from the former NKVD building in 2020—one commemorated the repressed in general, and the other one was dedicated to the executed Poles. Interestingly, the local authorities tried to publicly distance themselves from this act. The formal reason for the removal was that the plaques had allegedly been installed in the early 1990s without proper documents. The plaques were taken down at a time when the deniers of the NKVD’s responsibility for the executions in Katyn and Mednoye—Tver, Smolensk, and Moscow public activists and persons with academic degrees in history—stepped up their activity. A series of public events marked the formation of an interregional network of deniers, and the fact that some meetings were attended by people affiliated with the Russian Military Historical Society prompted external observers to suspect state support. Let us say that Russian Military Historical Society Chairman Vladimir Medinsky himself, being a deputy of the State Duma, supported the aforementioned statement in 2010.

* * *

We can see that references to the international dimension are tightly woven into regional historical identities. In some cases, this is a conscious choice of people engaged in memory politics, in other cases it is a derivative of the existing cultural heritage or actualized historical plots. If the past is likened to clay, then the freedom of sculpting is still limited by the properties of the material itself. The quantitative prevalence of the image of enemies is not a response to the “current conjuncture,” but something that is rooted in a long cultural tradition. There are more methods to understand ties with the outside world, which signifies the ability of local cultural elites to think independently and points to the fundamental impossibility of fitting history into given templates. “Russian antiquity,” just like the Russian province, is looking for conceptualization in international and transnational perspectives. While over the past ten years we have seen many examples of how local cultural elites have stepped up the discussion about the identity and agency of their communities, not without success, greater effort is needed to study the methods of work with the international space more thoroughly.

Battle on the Ice, 2018. Itog konferentsii “Ledovoye poboishche. Vzglyad iz XXI veka” [Results of the Conference “Battle on the Ice. A Glance from the 21st Century”]. In: Ledovoye Poboishche, 27 October. Available at: ледовое-побоище.рф/news-27-10-2018.html [Accessed 20 September 2022].

Borisov, N., 2018. Mikhail Tverskoi. Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya.

Bez Formata, 2016. Vladimirskye veterany i gosti iz Germanii navestili Dub druzhby [Veterans from Vladimir and Guests from Germany Have Visited the Friendship Oak Memorial]. Bez formata, 23 July. Available at: https://vladimir.bezformata.com/listnews/germanii-navestili-dub-druzhbi/47991622/ [Accessed 20 September 2022].

Kononov, V., 2016. Komu Sigismund Zhigimont [For Whom Sigismund Is Zhigimont]. Vladislav Kononov [website], 7 September. Available at: http://vkononov.ru/2016/09/komu-sigizmund-zhigimont/ [Accessed 20 September 2022].

Novgorod and Hanse, 2019. Novgorod i Ganza: okno v Evropu. Katalog [Novgorod and Hanse: A Window to Europe. Catalog]. Veliky Novgorod: Novgorodsky Culture Preserve.

Parts, L., 2022. V poiskakh istinnoi Rossii. Provintsiya v sovremenom natsionalisticheskom discurse [In Search of The True Russia. The Provinces in Contemporary Nationalist Discourse]. Bosto, St. Petersburg: Academic Studies Press.

Pilyak, S., 2021. Stenogramma tematicheskogo soveshchaniya ekspertov [Transcript of Expert Thematic Conference]. In: Muzefikatsiya fortifiktsionnykh sooruzheniy: problemy i puti ikh resheniya [Museum Exhibitions in Fortified Installations: Problems and Solutions]. Compiled by S. Pilyak. Smolensk, p. 19.

Razina, N. А., 2017. Pamyatniki Yaroslavova dvorishcha [Relics of the Yarolav Court]. Veliky Novgorod.

RVIO, 2020. 11 noyabrya v Kaluzhskoi oblasti otmechayut regionalny prazdnik [The Kaluga Region Is Celebrating a Regional Holiday on November 11th]. Rossiiskoye istoricheskoye obshchestvo, 11 November. Available at: https://historyrussia.org/otdeleniya/kaluga/novyj-regionalnyj-prazdnik-kaluzhskoj-zemli.html [Accessed 20 September 2022].

Shulepova, Ye., 2019. Den’ Stoyaniya na Ugre mozhet stat’ natsionalnoi pamyatnoi datoi [The Great Stand on the Ugra River May Become a National Memorable Date]. Rosiiskaya gazeta, 14 July. Available at: https://rg.ru/2019/07/14/reg-cfo/den-stoianiia-na-ugre-mozhet-stat-gosudarstvennoj-pamiatnoj-datoj.html [Accessed 20 September 2022].

Teller Report, 2021. The Remains of General Guden Were Sent from Moscow to Paris. Teller Report, 13 July [online]. Available at: https://www.tellerreport.com/tech/2021-07-13-the-remains-of-general-guden-were-sent-from-moscow-to-paris.H1gZbfQeop_.html