Since its ascent to power in 2002, the right-wing Justice and Development Party (AKP) has presided over wholesale social, economic, and political transformations. Over the last 15 years, the support of Turkey’s predominantly conservative society has enabled the government to gain maximum political leverage. Although the 30% rule – with 30% of the population in favor, 30% opposed, and 30% indifferent (“waterpipe smokers”) – is not irrelevant to virtually all the key issues, the Turkish republic is unprecedentedly divided ahead of the 16 April referendum to amend the Constitution.

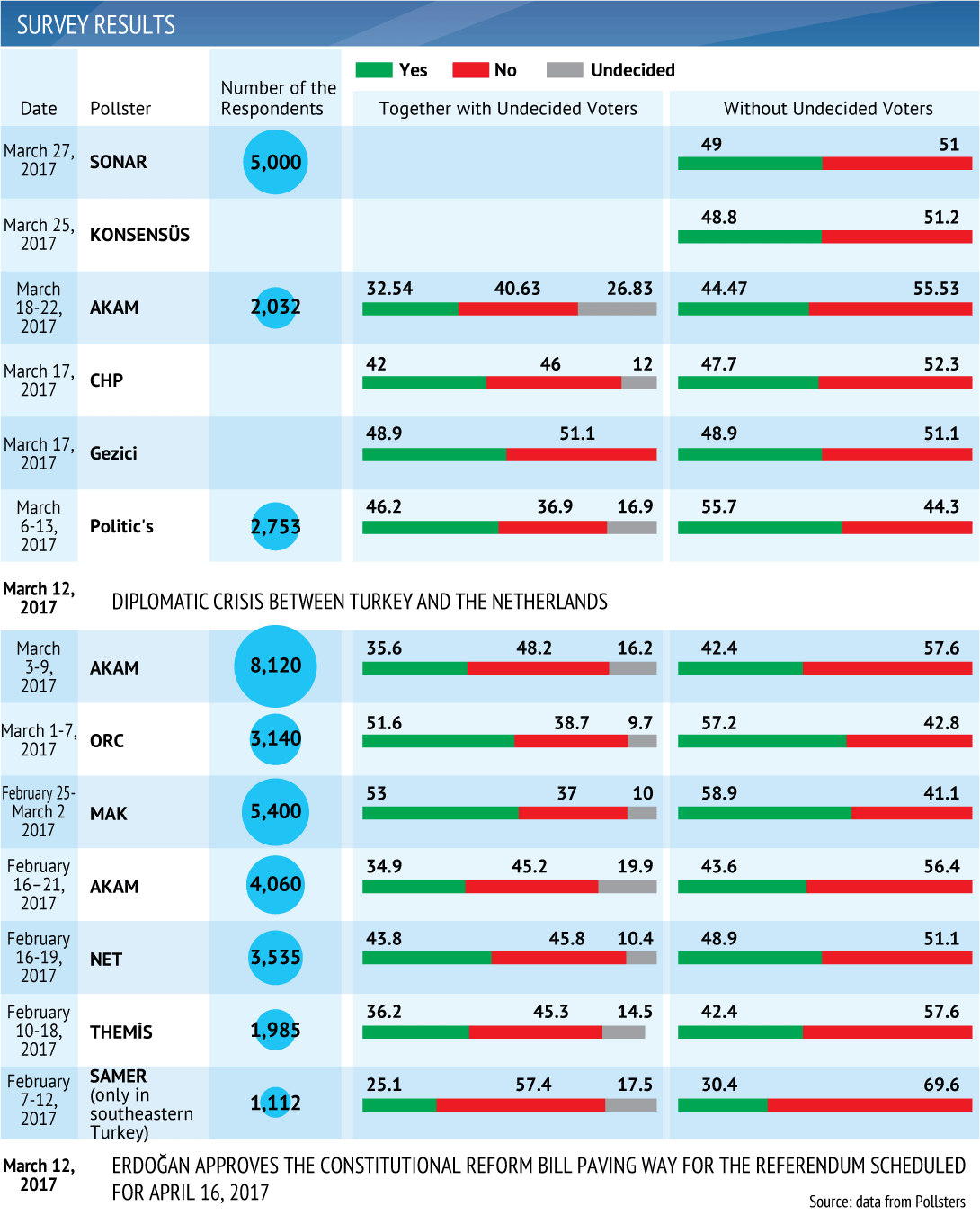

Recent polls indicate that the number of those who support or oppose the upcoming constitutional referendum ranges from 45% to 55%, depending on the political climate and the government’s and the opposition’s rhetoric. The pro-reform campaign of the establishment peaked at a time when rallies were organized by Recep Tayyip Erdo?an, Turkey’s charismatic and popular president, when the country enjoyed military success or when the images of political enemies “standing in the way of democracy”, such as the Netherlands and Germany, were presented to the masses.

Such political tricks resonating with the general public typify any country. However, the current situation demonstrates that Turkish society is on the verge of splitting apart. As a member of the ruling AK party put it, the failure of “Yes” vote supporters to cross the 50% threshold would cause a civil war. Given the statement, one should put forward several hypotheses about the likelihood of internal confrontation and of Middle Eastern chaos spilling over into Turkey. The “Yes” camp backed by 55% of Turks will make violent clashes most unlikely, while a 49:51 vote in favor of either side will have the opposite effect. The chance of those campaigning for “No” to win hearts and minds in Turkey deserves particular attention as their victory may push the political elites into imposing a de facto presidential system on the country without democratic procedures.

It is the proposed amendments that, above all, highlight the importance of the plebiscite. They would concentrate power in the hands of the presidency, with the role of the prime minister scrapped. The military, which has previously served as the guardian of the country’s secularism, would be denied access to power. The age requirement to stand as a candidate in an election would be lowered from 25 to 18. Should Turks cast their ballot for Erdo?an’s plan, this would limit the scope for the executive’s accountability to the legislature and would raise the number of seats in the Parliament from 550 to 600. In total, there are 18 amendments to be voted in the nationwide referendum. However, the listed points are of greatest significance.

Turkey has a parliamentary-based political system, where parties and their heads have traditionally played a crucial role. Although parties were largely inseparable from their leader and were dramatically transformed after his resignation or removal, they did define the political spectrum.

The main fault line lay between “secularism and non-secularism”. Conservatives rallied around parties with names like “Justice”, “Virtue”, thus claiming to command broad popular support while stressing their identification. When the Constitutional Court or the army dissolved any party, new groups with similar names came into existence.

Obviously, the army played a part in preventing the comeback of conservatism and suppressing anti-Western sentiments. Whereas the secular government largely struck a chord with many nations, the fight against communism and the idealization of the West as a lodestar were received with great skepticism. Actually, the majority of Turks are clearly weary of both too much secularism and pro-Western policies.

Ankara’s own political traditions or expansionism and nationalism may become new pillars of the country’s development. From this perspective, “neo-pan-Turkism” and “neo-Ottomanism” constitute most popular conceptions. To a certain extent, one can state that the latter represents Turkey’s informal foreign policy doctrine seeking to project soft power – shared identity alongside economic and humanitarian influence – into the wider region. Essentially, neo-Ottomanism is an unofficial creed embracing a wide range of Turkey’s foreign policy principles and practices. As an umbrella ideology, neo-Ottomanism includes such major aspects as neo-pan-Turkism, pan-Islamism, Turkish Eurasianism, as well as interaction with countries of the Arab world, the Balkan region, Asia, and Africa. With each individual element enabling Turkey to follow neo-Ottoman policies, the country generally aims to forge a new sub-ethnic identity of Ottoman imperialism by encouraging increased engagement in the regions through soft power. In its turn, neo-pan-Turkism implies, above all, the use of humanitarian and economic instruments to unite all Turkic peoples based on their linguistic, ethnic, and religious affinity [1].

A powerful leader is needed to implement any national idea. Given the surge of nationalist and conservative sentiments, sooner or later Turkey was to find an East-oriented alternative to pro-Western policies. Basically, it was offered by Recep Tayyip Erdo?an and his administration. The president’s impulsiveness had a negative impact on his foreign policy strategy, “zero problems with neighbors”, which the media even renamed to “zero neighbors – zero problems”.

At the same time, one should point out that the adopted doctrine “zero problems with neighbors” is fanciful and can hardly be applied even in the long-term perspective. However, Turkey’s long-term capabilities should not be underestimated, as it has established various mechanisms to form interest groups in neighboring countries. They have already started to prove themselves effective, particularly in post-Soviet states. Such organizations are underpinned by numerous business-structures and Turkey-affiliated international organization, involving the International Organization of Turkic Culture, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency, and the Turkic Council.

Erdo?anism did not come out of the blue. His appearance on the Turkish political stage represents a logical by-product of the relentless Westernization of the conservative country. Not only did his rise to power largely mark Turkey’s weariness of the West, but his ascend also gave rise to much speculation among academic circles.

Specifically, there is a prevailing opinion that the United States concerned with preserving its partnership with Turkey as the key NATO ally on a regional scale decided to try different instruments of regime change, with the country itself remaining loyal to Washington. The list includes evolutionary and revolutionary methods to change regimes. Unlike the Arab World, Ankara tried evolution.

Even if the suggestion allows for rationality, it is clear that the West has failed to put into practice either of the doctrines.

Indeed, the AK party initially comprised a wide range of moderate Islamic actors from different social classes. The great number of policymakers allowed some scope for third forces’ manipulation. Moreover, most of them had close ties with “green capital” and different American organizations.

Amid the intense struggle for power, the number of factions within the AK party started to gradually decline. Ultimately, Recep Tayyip Erdo?an emerged as a central figure of the party and Turkey’s political elites. He established himself as a strong leader who launched a campaign to transform Turkey into a regional and then world powerhouse.

Whether such overriding ambitions can be achieved or not, one should point out that the very political goal-setting has a positive impact on the electorate still typified by imperialist attitudes.

As of now, Turkey’s political consciousness marries two opposing elements. On the one hand, the public suffer from the Sèvres syndrome, implying that outside forces are conspiring to weaken and carve up their country, and the Kurdish syndrome suggesting Turkey’s federalization. On the other hand, Turks seek to extend their influence over Turkic and Ottoman regions.

Ankara’s fears and ambitions are skillfully exploited by Western partners maintaining close ties with both Kurdish interest groups and nationalist forces within Turkey’s borders.

Needless to say, internal and external challenges made Turkey assume leadership for defense purposes. That is the reason why Recep Tayyip Erdo?an took the helm, with Turkish troops currently being deployed both in Syria and Iraq.

With this in mind, one should examine the establishment’s slogans and statements.

When it comes to world politics, Turkey’s catchphrase “The world is bigger than five” constitutes a key slogan. Such an ideologeme has repeatedly been highlighted by President Erdo?an to display his willingness to reform the UN Security Council, which, as he said, lacks a Muslim permanent member.

The Turkish authorities are spreading their somewhat aggressive messages across the region. Ankara is constantly sending signals that the 1923 Lausanne Treaty, which imposed artificial borders throughout the Middle East, is at odds with natural aspirations of societies and peoples. While this idea was initially associated only with the Turkish-Greek dispute over some Aegean islands, it was gradually applied to the country’s south-eastern borders. At the same time, Turkey does not question the Caucasian borders as of now, as the geopolitical zone remains under Russia’s strong influence. Moreover, there is a need for Turkey to wait until a new generation of Georgian and Azerbaijani politicians, most of whom have received education in Turkey and have links with Turkish business and relevant political consciousness, grows up.

Turkey’s ideologemes imply fighting against outside forces, and stressing nationalist and conservative values. In this context, security hailed as the sacred cow constitutes the bedrock of the internal political process. The electoral campaign ahead of the recent parliamentary elections was centered around the issue of security, and so is the current referendum campaign. The main narrative goes as follows. As there are terrorist groups seeking to destroy the country, only joint efforts can eliminate all “alien elements”. This raises a logical question, which actors will be considered “alien”.

Generally, collective consciousness of Eastern societies suggests a crackdown on the dissent, slow social development, and instantaneous unification in case of emergency. In practice, Turkey integrating Eastern and Western characteristics and political consciousness, finds itself more ready to adopt the former’s ideas and practices.

As of now, most Turks share the idea of combating the Gülenist Terror Organisation (Fethullahç? Terör Örgütü, FETÖ) in spite of the fact that until recently Erdo?an and Gülen, a US resident, had a de facto alliance. Yet the struggle for power – both in political and broader spheres – pits the actors against each other which earlier formed the basis for the Turkish elite.

Fethullah Gülen, a prominent philosopher and political figure, is straining to build a new “golden generation”, primarily through education. It was upbringing of a young generation and head-hunting which the Turkish cleric hoped to use in order to produce a new person who would be committed to both Islam and “Turkish national objectives” and would become part of the big pyramid of interest groups. To that end, numerous organizations were set up. Despite the absence of formal ties with Gülen, they wielded profound influence within the pyramid. The Gülenist movement placed great stress on “the Turkic world”, a sub-system of international relations that Ankara was desperately trying to devise. However, Gülenist structures remain commonplace in the major world powers, including the USA and Russia. Although such bodies adversely affect these countries’ national interests, they are hardly traceable, with their negative activities being difficult to prove. At the same time, they may exert a significant impact on shaping interest groups in the mid- and long-term perspective.

Actually, the above mentioned causes do not account for Turkey’s decision to counter the Gülenist Terror Organisation, as the interest group formation is indispensable to the country’s foreign policy strategy. Power is the reason behind Ankara’s conduct. President Erdo?an and his team clearly realized that Gülen-affiliated network organizations, infiltrating Turkey’s state institutions, may only temporarily back the regime. At the same time, Turkey allows far more scope for getting a better sense of who’s who than other countries which are ill-fitted for fighting such groupings.

Last summer’s failed military coup was a catalyst for the “purges”. The military hadpreviously mounted coups to preserve Turkey’s pro-Western and secular orientation. However, over the past decade, they have had to withstand Brussels’ intense pressure as the latter has been seeking to democratize the EU candidate. Moreover, it has had to resist a large-amount of administrative arm-twisting since the authorities have been struggling for survival. In effect, the EU democratization efforts resulted in a more conservative stance adopted by Turkish society. The military chased rainbows and sacrificed its political role for the sake of an illusory goal to become an EU member. Curiously, the states which had not promoted such ideas, have escaped the Turkish fate. For instance, Egyptian generals clung to power and avoided an ouster, which prevented Islamists from tightening their grip on power.

By the summer of 2016 the army had little, if any, political leverage. Mostly supporters of the ruling elite, including FETÖ members, joined its ranks. Given that Erdo?an made the fight against old secular elites and FETÖ the cornerstone of his domestic policy, the coup played into his hands allowing the President to achieve his ends.

The Turkish coup was poorly organized and sloppily perpetrated. It was very much unlike the plot which could be expected of the adept officers. By blocking the bridges, seizing control of a state broadcaster, bombing parliament and the hotel where Erdo?an was allegedly hiding, they demonstrated either the amateurish level of planning or intentional negligence.

The authorities were quick to implicate the opposition, that is Fethullah Gülen’s followers. Given ample intelligence collected by the special services, it is unlikely that they were unaware of the planned coup. Hakan Fidan, Chief of the National Intelligence Organization, is, after all, Erdo?an’s close associate.

The failed coup played right into the regime’s hands. On the one hand, it discredited the military as a political actor; on the other hand, it allowed the nation to unite against the looming internal and external threat of terrorism, which was the government’s aim. Every political dispute in Turkey has recently revolved around the fight against terrorism, with Fethullah Gülen, Kurdish groups, and external “enemies” being the scapegoats. It produced the necessary internal and external forces to add to the friend/enemy paradigm.

The Gülenists pose a threat to Russia, to the CIS, and to other actors of world politics. They corrode the identity of the peoples and give impetus to globalization. The major players have yet to become fully aware of the danger. While they are now trying to realize it, they have not yet moved from identification to resistance. Russia is, in many respects, an exception whose security forces have long been fighting educational sects. Unfortunately, the campaign has not been equally successful across the country. Pan-Turkist groups and their ideology still exert significant influence, and some Turkic-speaking regions even see this influence grow.

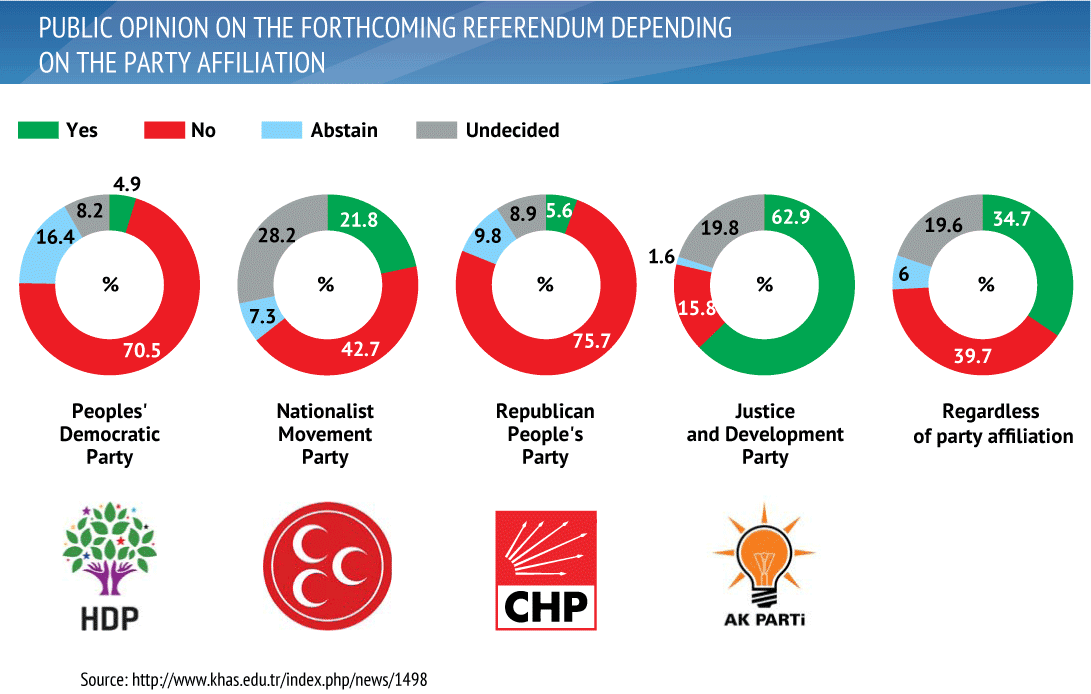

The summer’s odd failed coup attempt gave Erdo?an carte blanche to carry through the reforms and rallied the masses around him. But the images relying on the friend/foe principle are short-lived. The authorities have apparently been losing popular support as they have been cracking down on any unwelcome dissent as well as the Gülenists. Moreover, nationalists are gradually merging with the powers that be. In fact, the opposition nowadays is comprised of liberals and social democrats who have always constituted less that 50% of the population and who have recently gone into decline.

It is noteworthy that Erdo?an’s public support has always been strong, with the presidential approval rating fluctuating from 40% to 65%. However, fewer people approve of the constitutional reforms. The figure reveals a lower dependence of people’s preferences on the leader’s charismatic personality. It points to a relative success of parliamentarism, which took root in Turkish soil about a hundred years ago. Paradoxically, now that these minor shifts can be observed, Turkish society is encouraged to modify the system to introduce a stronger model, the presidential republic.

The population is ready to back Erdo?an’s policy, but ahead of the vote they are considering institutional transformations, which could impact on the future of Turkey, rather than the President’s character traits. In many respects, the April referendum is on the future of the system which will outlive the current president, rather than on the constitution or Erdo?an. Even the medium-educated supporters of the President are aware of it, and many of them are going to vote against.

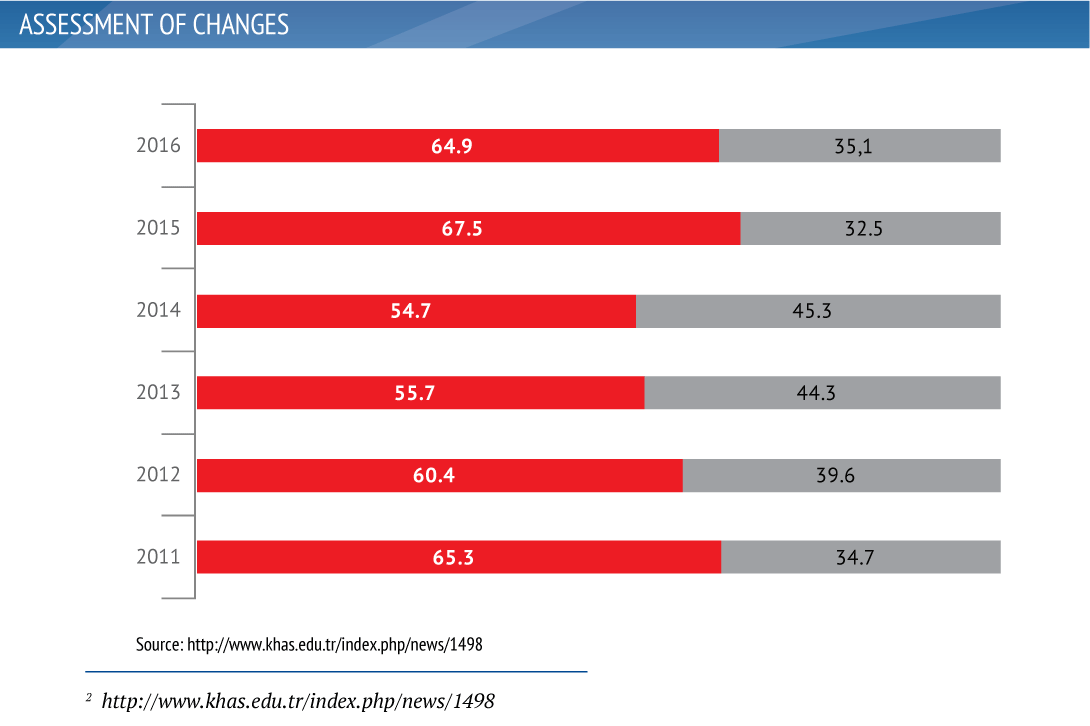

The results vary insigni?cantly. However, when a margin is narrow and votes are almost equally distributed, each vote matters. The Kadir Has University2 conducted a curious opinion poll, which showed the result for each social group and took into account the group’s support for the authorities. The survey showed that:

- the population considers the ?ght against FETÖ the main accomplishment of 2016;

- the majority agrees to the state of emergency, but people do not want their country to be under it for long;

- only 32% of the population give their wholehearted support to the presidential republic, while other supports voice reservations;

- the popularity of the army has been declining;

- the pro-European enthusiasm has been fading, with proponents of European integration constituting 45% in 2016, down from 65% in 2015;

- Israel, followed by the United States and Syria, are now regarded as the three most dangerous countries for Turkey, while Russia was considered the major threat back in 2015.

In general, Turks are well disposed to the ongoing transformation. The red part of the chart shows the number of those who consider it advantageous to the country while the grey part shows those skeptical of the reforms.

In the run-up to the referendum the authorities and the parties have focused on rallying support of the undecided voters who are still going to cast their ballot. To secure a victory, Erdo?an’s team will step up its efforts to clamp down on the dissent. Moreover, it will further elaborate the images of the country’s external and internal foes as it needs great triumphs and minor successes, as well as a larger number of trouble spots and challenges for people to rally behind the authorities. In this context, a war of words between Turkey and the Netherlands may not be the worst manifestation of the campaign.

***

The pivot to the East, the search for a new ideological agenda, and the attempt to determine best interests have ranked high in Turkey’s foreign policy. Both society and the elite are apparently divided on the practical and theoretical foreign policy framework. The advance of the presidential republic, which will replace the parliamentary system, will give the head of the state a free hand to decide on the priorities and will vest him with greater responsibility for the future of the state.

The European dream which has been central to the Turkish foreign policy has run out of steam. The EU accession bid has stimulated reforms, which strengthened the country. Moreover, the authorities have shored up the economy and adopted a more assertive foreign policy stance.

The Arab world has become a top priority for Turkey. Meanwhile, the Arab Spring caught the Turkish authorities off guard, with Ankara blamed for inaction. Unable to catch up with the regional processes, the administration decided to take the lead and headed the movement, which proved sympathetic to the country’s conservative regime in many ways. Thus, Turkey cultivated friendly relations with Egypt’s regime. Erdo?an and his team fought for it right till the bitter end, accusing the military of illegally deposing the Egyptian government.

Moreover, while watching the revolutionary wave sweeping across the region, Ankara decided to take a proactive approach since it hoped that the regime in Syria would fall as swiftly as in Libya and Egypt. Syria and Turkey’s political relationship has historically been complicated by ethnic, religious and territorial issues. Moreover, as part of its “zero problems” policy, Turkey sought a regime change in neighboring Syria and was eager to install a government which was more sympathetic both to Turkey and the Arab states. It was important economically as well as geostrategically.

After 2010, Turkey entered the phase of “perestroika”. It tried to find a new place in world and regional politics. Among other things, the overthrow of the Syrian regime was expected to facilitate the construction of a gas pipeline from the Arab states through Turkey to Europe. To this end, it was vital to win over Damascus, which preferred to align with Tehran and Moscow.

Prior to the start of the con?ict, the relations between Recep Tayyip Erdo?an and Bashar al-Assad used to be close and friendly, with their families spending holidays together. The Turkish government performed a U-turn overnight as it declared the situation in the neighboring state part of Turkey’s internal affairs and was among the ?rst to stick the label of a “dictator” on the Syrian leader.

However, Turkey bit off more than it could chew as it was guided by ambitions rather that the assessment of the available resources. In addition, Ankara did not take into account Russia’s possible engagement in regional affairs. Moscow was eradicating terrorism in Syria at the formal request of the ruling regime, which made its position legitimate and put Arab and Turkish partners in a predicament.

Arab states avoided direct confrontation with Russia while Turkey, which needed “an external enemy” ahead of the elections and sustained political and economic losses after severing ties with many interest groups, opted for a face-off and shot down a Russian jet.

Russia did not expect “the stab in the back”, even though betrayals are not uncommon in wartime, especially given the complicated situation which emerged after the collapse of the USSR. Ankara took advantage of Russia’s trust and showed the world its true colors. The bene?ts derived from strong economic ties failed to outweigh geopolitical and ideological differences, which was a heavy blow to the supporters of the Russia-Turkey alliance.

To systemically strengthen bilateral ties it was important – and it is still necessary – to cultivate economic relations and, importantly, coordinate efforts in many other sectors. Any lack of balance is fraught with crises, which are dif?cult to overcome later.

Correlating Russia’s interests and values with Turkey’s ones – that is relevant to any state, in fact – does not necessarily produce a positive outcome. However, these efforts can, at the very least, help to draw red lines. Moreover, this work should be carried out through of?cial channels, as well as through public diplomacy and communication at all levels, including the engagement of the expert community.

Adopting an open-eyed approach instead of seeing partners through rose-colored spectacles proves the most reliable approach amid global and regional confrontation. Apart from possible economic bene?ts, one should also consider the partner’s values which may be part of an ideological pattern, but can often contradict economic imperatives.

Erdo?an’s striving for the “pivot to the East” does not necessarily imply good relations with Moscow. Moreover, the Turkish authorities are constantly walking a tightrope between expansionism and nationalism, on the one hand, and focus on national prosperity, on the other. Regional developments show that despite Ankara’s readiness to have a dialogue with Moscow, it is not going to renounce its expansionist ambitions. Meanwhile, the dialogue is vital if only from the point of view that Turkey restrains its ambitions, takes a seat at the negotiating table and forces loyal groups, in particular Syrian opposition groups, to follow suit.

The positive result of the Astana talks mediated by Moscow, Ankara and Tehran, is a worthy end. However, they are even more important as a platform for dialogue between different parties. It is the only way to build a viable regional security architecture.

***

In the run-up to the referendum, Turkey is facing a number of internal and foreign policy challenges, including a state of emergency and troops stationed in Iraq and Syria. The country is witnessing a crackdown on “Kurdish separatists”, Gülen’s supporters, and the opposition.

The emergence of Recep Tayyip Erdo?an and his team is a natural continuation of Turkish policies in the twentieth century rather than a deviation. This is a logical result of imposed Westernization. However, his power is obviously constrained by internal and external factors, including the United States and Russia. The extremes characteristic of Turkish political consciousness can be encouraged by the inaction on the part of internal and external players, or can be reined in.

The April 16 referendum will focus on power distribution rather than institution-building. In other words, the organizers saw it as an opportunity to expand the President’s powers and allow him to rule longer. In their turn, Turks perceived it as an institutional choice to contribute to the development of the state. In this regard, the referendum will revolve around speci?c changes in the political system rather than be the one about Erdo?an.

The referendum’s outcome will directly affect the political system, as well as President Erdo?an’s powers. Moreover, the very vote on fundamental issues is dangerous given the chaos in neighboring states, clashes and terror attacks in the country, flows of migrants crossing the Turkish territory on their way to the EU. The domino effect is something Russia and the world should be most wary of as the events in Turkey could set off a chain reaction in the neighboring countries, in particular, in Transcaucasia.

The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Valdai International Discussion Club