First published in Russian in Nezavisimaya Gazeta.

Someone may find the idea strange of a link between demography and terrorism. Is this plausible or is it far-fetched?

The meaning of my reflections is that the demographic component of what we now call international terrorism (although I am not sure that this is an accurate definition of what is happening today) is very important, yet I certainly do not mean to assert that only demographic events and processes fuel terrorism. Nevertheless, understanding the essence of global demographic processes has made it possible to foresee the present growth of terrorist threats long before they became a stark reality of our world today.

THE “THIRD WORLD” OF ALFRED SAUVY

From a global perspective, the most obvious link is between these threats and what is called population explosion; that is, the greatly increased birth rate in the world after World War II. Demographers foresaw a “demographic tsunami” 50 to 70 years ago.

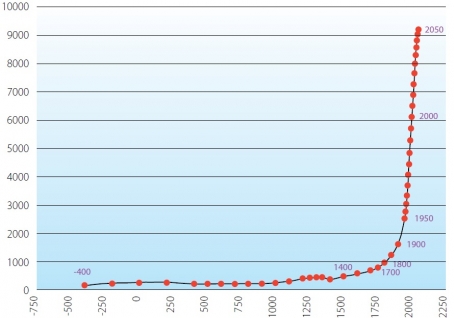

The world’s population has always grown very slowly. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Earth’s population for the first time approached one billion people. In the 18th century enlightened Europeans argued about whether the European population was growing at all, but by the end of the century it was already clear: it was—and faster than usual. At that time Thomas Malthus proposed checking population growth. However, during the next 150 years the problem of population growth did not feature prominently in the global agenda, although the world population increased by another 1.5 billion people over that time.

It was only after World War II, when the population of developing countries began to grow rapidly, that signs emerged of potential threats related to demography. Demographers were, perhaps, the first to realize that. It was French demographer Alfred Sauvy who coined the term “Third World” to distinguish this world of rapid population growth from the other two worlds—capitalist and socialist—where nothing like that was happening.

At that time not everything was clear. In 1950 the world population was 2.5 billion people. According to the first postwar UN forecast (1951), the number of people in the world was expected to increase to 3.3 billion by 1980. Actually, the population exceeded this forecast already in 1965, and in 1980 the number of people on the planet grew to more than 4.4 billion. Nevertheless, in the early 1950s there were those who understood that unprecedented population growth in the Third World posed a great danger. Sauvy warned that “this ignored, exploited, and scorned Third World, like the Third Estate, wants to become something too.” This phrase hints at a possible revolt of the Third World—it was not accidental that it mentions the “third estate” and alludes to a line from “The Internationale:” “We have been nought, we shall be all!”

The reasons for the population explosion were very simple. After World War II, the achievements of modern medicine in the developed world began to spread to developing countries, which led to a rapid decline in mortality rates there. The reproductive behavior of people remained the same and birth rates were high. Fertility and mortality rates went out of balance, but restoring the balance meant reducing birth rates.

Birth rates in Europe used to be high too, but starting in the 18th century, death rates declined slowly and gradually, and birth rates had enough time to adapt to changes in mortality. However, Europe failed to immediately restore the balance and prevent a population explosion of its own in the 19th century. But this explosion was much weaker. In addition, Europe got rid of much of its excess population by sending great numbers of people to the New World. Given the rate of decline in mortality in developing countries, a special demographic policy needed to be adopted to accelerate a decline in birth rates.

Fig. 1. World population growth from 400 B.C. to 2050 (UN forecast), mln people

Sources: Jean-Noël Birabin. The History of Human Population from the Very Beginnings to the Present Days // Demography: Analysis and Synthesis. Elsevier, 2006. Vol. III, p. 13; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, DVD Edition.

Sources: Jean-Noël Birabin. The History of Human Population from the Very Beginnings to the Present Days // Demography: Analysis and Synthesis. Elsevier, 2006. Vol. III, p. 13; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, DVD Edition.

Demographers and politicians, including leaders of developing countries, grew increasingly aware of the need for a new policy. However, traditionalist societies resisted those efforts. There was also no unanimity in the two worlds that were particularly threatened by population growth in the Third World.

In particular and contrary to its own interests, the Soviet Union was opposed to programs designed to reduce birth rates. Here is an excerpt from a typical speech by a high-ranking Soviet official (1969): “On December 10, 1966, twelve states—India, Malaysia, South Korea, Tunisia, Sweden, Yugoslavia, etc.—signed a declaration on the need to conduct a family planning policy. David Rockefeller exerted much effort to collect signatures under this declaration. […] Rockefeller’s efforts in the family planning issue are understandable: a large-scale implementation of this policy will bring capitalist monopolies huge profits from the sale of contraceptives. […] The Soviet government, after a thorough discussion of this issue, including at the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, decided not to join the Declaration and stated that purely demographic methods of regulating population dynamics are not essential.”

The U.S. position was more sober at first. In 1974, the U.S. National Security Council prepared a memorandum on the implications of worldwide population growth for U.S. security and overseas interests, which clearly identified possible threats: “World population growth is widely recognized within the (U.S.) Government as a current danger of the highest magnitude calling for urgent measures. […] Population factors are crucial in, and often determinants of, violent conflicts in developing areas. […] Conflicts that are regarded in primarily political terms often have demographic roots. Recognition of these relationships appears crucial to any understanding or prevention of such hostilities. […] Where population size is greater than available resources, or is expanding more rapidly than the available resources, there is a tendency toward internal disorders and violence and, sometimes, disruptive international policies or violence. […] In developing countries, the burden of population factors, added to others, will weaken unstable governments, often only marginally effective in good times, and open the way for extremist regimes.”

However, the U.S. position was inconsistent as well. During the presidency of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, conservative views prevailed in Washington and were reflected in the activity of American opponents of abortion, although abortion as a family planning tool played a less significant role after the “contraceptive revolution.” The U.S. stopped supporting international family planning programs. But now its position was less important, because increasingly more politicians in developing countries realized the need to reduce birth rates, and those countries adopted corresponding policies.

I will not go into detail about how various countries sought to solve this problem. Everyone is familiar with the experience of China, a country that pursued a strict demographic policy and achieved a fast decline in birth rates, albeit with some unfavorable demographic consequences. Although less well known Iran’s experience is also very instructive.

WHAT “AMERICAN FASCISM” SOUGHT TO ACHIEVE

I was honored to meet with the Russian president during his first term in office. I showed him a list of countries that, according to a UN forecast, could overtake Russia in terms of population. He immediately noted that Iran could be among the first to do so. It was a forecast from 2000, and now we know that it has not materialized and is not likely to happen. Why?

At about the same time, I read the following text on a Russian Orthodox website: “The Iranian shah was a great friend of the United States. […] He launched an active family planning policy in his country. The Ministry of Education revised school curricula, issued new textbooks that now included information on sex and contraception, and retrained teachers to teach sex education. Thousands of highly paid healthcare workers sought to prevent ‘unwanted children’.” […] But later, the shah was overthrown and the Ayatollah Khomeini fired all family planners, together with their American sponsors. But, alas, those were only isolated cases. One has to admit that, on the whole, American fascism has won.”

Apparently, the victory of “American fascism” in this text meant the spread in developing countries of family planning and birth control practices; that is, the very type of demographic behavior that prevails in all developed countries, including Russia. But if the authors of the text were informed about what they had written, they would have to admit that it was in Iran that “American fascism” scored its largest victory (after China).

A year after the Islamic Revolution, the Ayatollah Khomeini approved the use of contraception in his fatwa in 1980. The fatwa stated that “the use of contraceptives with the knowledge and consent of the husband, if it does not threaten the health of the spouses, is not contrary to Islamic principles.” In 1989, prominent Iranian demographer Mohammad Abbasi-Shavazi wrote: “The government made a U-turn in demographic orientation by adopting a family planning program. By all indications it was a success: the level of contraceptive use increased from 37 percent in 1976 to 75 percent in 2000. The growth in rural areas was from 20 to 72 percent, and in urban areas from 54 to 82 percent.”

Very soon birth rates in Iran began to decline rapidly, but it was not the only Islamic country to achieve that. Many people still view Arab Middle Eastern countries as an outpost of high birth rates, but this is already history for most of them. In the 1950s Israel was the only country in the region with relatively low birth rates. At the beginning of the 21st century, birth rates in Israel were already higher than in most of these countries, with the lowest birth rates registered in Iran.

Birth rates have been decreasing in most developing countries, even in Africa, although the decline there has been very slow. Overall, population growth rates in the Third World are gradually slowing, which provides grounds to confidently predict the end of the population explosion, although only by the end of the twenty-first century.

WORLD ASYMMETRY

But even with this relatively optimistic prospect, the world’s population is expected to increase to nine billion people by 2050 and to eleven billion by the end of the century. Clearly, constant population growth has radically changed the global demographic and therefore the geopolitical situation. These changes have diverse and very serious consequences—economic, environmental, and others, but I would like to focus on the emergence of an unprecedented demographic asymmetry in the world today, because answers to global economic, environmental, or political challenges will have to be found in conditions of this asymmetry.

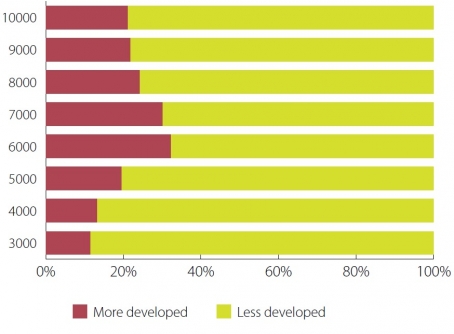

If we look at Fig. 2, we can see that the bulk of the world population has always lived in countries we now call developing. Yet until the middle of the twentieth century the share of developed countries increased and reached approximately one-third of the world’s population, after which it began to decrease. According to forecasts, the population of developed countries will fall below 12 percent of the total population by the year 2100.

Fig. 2. Fertility rate in Arab and Middle East countries

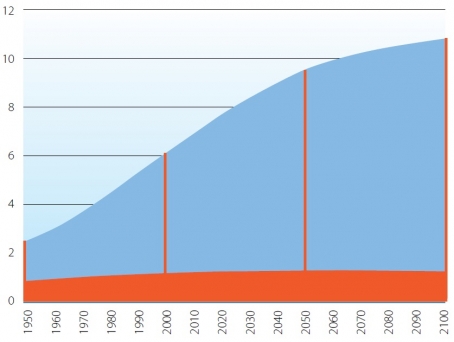

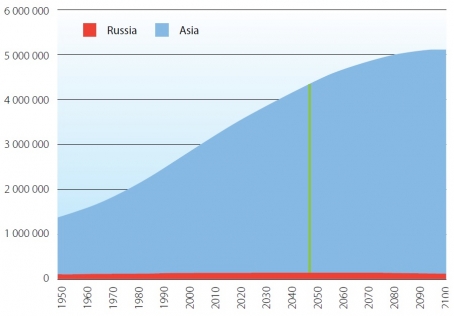

Fig. 3 shows the present and future unevenness in population growth rates in the world and in developed countries, including Russia. The demographic mass of developing countries in the Global South already hangs over the countries of the Global North, whose population is barely increasing. And this overhang will keep growing.

Fig. 3. More and less developed countries in world population

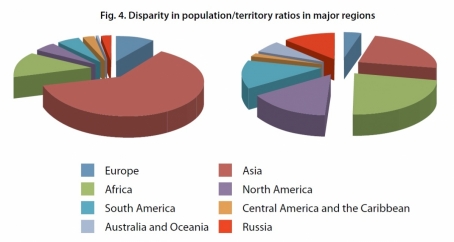

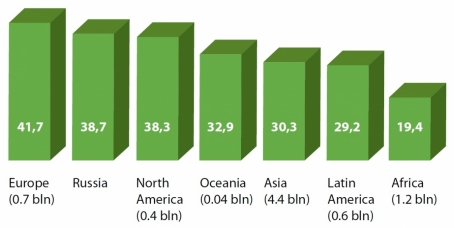

This expanding demographic asymmetry is coupled with territorial unevenness (see Fig. 4), not to mention economic asymmetry, and a huge gap between the rich demographic minority and the poor majority. Russia belongs to the demographic minority, but pretends not to notice.

Fig. 4. Disparity in population/territory ratios in major regions

The dramatic changes in the ratio between demographic masses are very important per se. but changes are taking place not only in the ratio of populations, but also in the balance of power. At present, the economic or military power of developed Northern countries is greater than that of developing countries of the Global South, but life does not remain still. Increasingly we hear that China is competing with the United States for the title of the world’s number one economy. Of course, if we speak of per capita income, China is still far behind the U.S. But if we speak of the aggregate income of that country with a population of 1.4 billion people, and of the possibility for concentrating enormous resources in the hands of the state, then its economic and military potentials look very serious.

All of these factors will have a huge impact on the destiny of our world in the 21st century. What will this impact be? And what place will countries in the “demographic majority” take in this world?

A BIT OF GEOPOLITICS

Oddly enough, our habitual system of views, apparently rooted in the Soviet era, does not assign an independent place to developing countries. The Soviet ideological mythology was based on the idea that the main content of the 20th-century era was “transition from capitalism to socialism” and the ensuing confrontation between the First and Second worlds. The other, or Third World, was vaguely described in terms of “national liberation revolutions” and “the elimination of the colonial system,” without clarifying what could be expected of these societies made up of billions of people, which had not even reached the stage of capitalism. Many still believe that no one on this planet should have a say, except Russia, the U.S., and Europe in the fate of these nations. Vladimir Zhirinovsky expressed this idea in a simple-minded way in his book Thrust to the South: “We should reach agreement […] that we divide the whole planet into spheres of economic influence and act along the North-South axis. The Japanese and Chinese extend their spheres of influence downwards, towards Southeast Asia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Australia. Russia projects its influence to the South: Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey. Western Europe—also to the South: the African continent. And finally, Canada and the U.S.—again to the South: the whole of Latin America. […] We would concentrate our economic ties mainly on Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey for as long as these countries exist […] and until they become part of the Russian state.”

Let me note parenthetically that the population of the countries Zhirinovsky mentioned, which he proposed incorporating into Russia, now stands at 190 million people. If they become part of the Russian state, it would cease to be Russian. The point, however, is not Zhirinovsky’s fantasies, but that we (and not only Zhirinovsky), while identifying ourselves as part of the Global North, still believe that we will continue, as before, to give orders to the Global South. However, the real future of Third World countries depends not on us, but on objective laws of development and the real challenges to which these countries will have to respond and determine their own trajectories of development.

We have never realized that these trajectories may pose potential risks not only to the vicious West, but also to the blameless us. We still view the world as “North-centric” and believe that its destiny is decided in international confrontation within the North; for example, in the confrontation between Russia and the United States. At the same time, the rest of the world plays the role of extras, depending on the outcome of this confrontation. This view may have been justified in the first half of the twentieth century, but no longer.

Three-quarters of Russian territory is in Asia, where it has the longest border, and we will certainly have the biggest problems there. To see this, just look at Fig. 6, which shows the ratio between the populations of Russia and the whole of Asia. Asia’s population already exceeds four billion people, and by the 2050 it will reach five billion. Russia’s population in its Asian part is less than 30 million. To hear some Russian geopoliticians talk, one might think there is no task more important to Russia than to lock horns with the U.S. and Europe. Meanwhile, Asia and Africa are repeatedly making themselves felt.

Fig. 5. Population in Russia and Asia; actual and as forecast by the UN, 1,000 people

How predictable are relationships between the global demographic minority and the global demographic majority? This largely or even decisively depends on how third world countries cope with their internal problems.

THE DIFFICULT PATH TO MODERNIZATION

Most Third World countries are poised to begin or have embarked on the path of modernization in the hope of catching up sooner or later with the developed countries, which are now way ahead of them. This catch-up modernization at first seems to be instrumental: developing countries borrow Western technologies, pharmaceuticals, and weapons, while trying to preserve, at least partially, traditional social relations, values, and norms. But attempts to combine the modern and the traditional always fail. Traditional attitudes and the traditional system of values succumb to the new social conditions—the spread of the power of money, population migration to cities, and universal education. Unprecedented demographic changes are another—and major—part of the new reality.

Demographic behavior is always very closely connected with the main existential human values, such as life, death, birth, sex, and interaction between the sexes. The attitude to these values forms the basis of any culture, is reflected in views of good and evil, of what is acceptable and unacceptable, and is codified in religious norms and secular laws.

It is hard to imagine more profound changes in all these fundamental aspects of life than those that are required by one of humankind’s greatest achievements—the unprecedented decline in mortality.

For example, consider how the role of women has changed. Europe has already forgotten about women’s positions, but in Islamic countries these issues are still relevant. Should women get an education? Should they be allowed to drive a car? Should they be allowed to vote? Should they be allowed to hold government positions? Can they have the same rights as men? All these issues are still subjects of discussion.

But if we must recognize and approve of family planning and low birth rates, then we cannot avoid a chain of unavoidable consequences affecting the entire system of traditional norms, which have for centuries regulated the private and family life of an individual, the institution of marriage, relationships between parents and children and between husband and wife, the family and social roles of men and women, and family values. The new demographic conditions give women more freedom. Nothing can stop radical changes in their position in family and society.

Whether we want it or not, this is just one example to show that demographic innovations are becoming one of the sharpest wedges splitting the traditional order.

Demographic changes affect virtually everyone. All families almost simultaneously are involved in these changes and begin to feel or at least understand that life requires that people forsake much of what they thought was sacred even yesterday. New moral norms and rules of conduct are needed, and values should be reassessed. It took Europeans centuries to reassess their values, but societies in developing countries do not have that much time now. Changes are accomplished within the lifetime of one generation.

When faced with a stream of rapid and profound changes (and demographic changes are only part of this stream, albeit a very important one), few countries manage to avoid difficulties during the transition period, including a sharp conflict within culture and society, an identity crisis, a cultural split, and the emergence of fanatical supporters of the new and no less fanatical defenders of the old.

This is a very painful period for any society. It finds itself at a crossroads, which one African anthropologist figuratively described by quoting two conflicting African proverbs: “It is better to destroy a village than destroy a custom” and “When the river changes direction, the crocodile follows it.”

Fig. 6. Median age of the population of major regions

Changes, including demographic ones, occur in societies that have already been affected in various degrees by modernization. Such societies are already in motion and have begun to move away from a patriarchal order towards urbanization. Various intermediary and marginal social groups emerge, which are semi-rural and semi-urban. Those groups are semi-literate and are experiencing a cultural identity crisis and split. Neither men nor women are content with the old ways any longer, but they are not ready to fully accept the new ones either. So they are at a crossroads. The absence of any solid ground makes them very susceptible to simplistic “fundamentalist” ideas, which they think will help them to get rid of their cultural split and become their own selves again.

There are billions of such people.

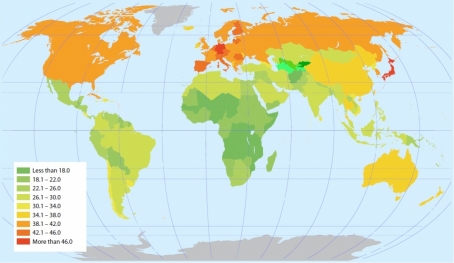

The situation is further complicated by one more demographic factor: the population of a majority of developing countries is very young.

The so-called median age of the Russian population is 39 years. This means that half of Russians are younger and the other half is older. In Syria, half of the population is under the age of 21, and in Nigeria half of the population is younger than 18 years.

A huge number of young people and teenagers, whether partly educated or not educated at all, who do not see any prospects for the future, and who grow up in poor and marginalizing societies, are easily susceptible to manipulation through catchy slogans that require no understanding, but blind faith.

LOOKING FOR THE GUILTY

Russia’s population stood at 101 million in 1950 and was already at 144 million (without Crimea) in 2015; thus, the population grew by less than half. Over the same period, the population of Nigeria increased from 39 million people to 182 million, or 4.5-fold over 65 years because of an unprecedented decline in death rates. Infant mortality in Nigeria has since decreased from 201 in 1950 to 76 per 1,000 births (Russia’s level in 1955), while birth rates have decreased very little—from 6.4 to 5.7 births per woman. According to a UN forecast, Nigeria’s population may reach 500 million people by 2050.

The huge problems posed by rapid population growth for Nigeria are clear. In fact, Nigeria knows how important economic, social, and demographic modernization is to the country. Modernization can help to minimize or even prevent growing tensions and stop the continuing population explosion. However, in demography, like in other spheres, modernization generates huge conflicts. One of the reasons is the cultural split that always accompanies a transition from the old to the new, especially if the transition is fast.

Fig. 7 Median age of population by country

The main sources of cultural conflict are in the very development of these countries, which changes the habitual situation (generally to the benefit of society). Yet as a rule defenders of the old order do not recognize the internal nature of the conflict and seek its origins in an imported “contagion,” a foreign conspiracy, or the activities of foreign agents, thus forming the image of a hated foreign enemy. Most often this enemy is the West. This is not a geographical term, but a symbolic designation of everything that accompanies modernization and which does not fit into the system of traditional values inherited from the past eras.

This is an old story. The dispute is well known between Slavophiles and Westernizers in 19th-century Russia. Nikolai Danilevsky wrote that “the struggle with the West is the only remedy against our Russian cultural ailments.” But Slavophiles were disciples of Germans, who also fought with the West—only the West for them began west of the Rhine. Oswald Spengler’s best-known book is called Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the West). So it is little surprise that slogans calling for struggle against the West are written on banners of fighters against their own “cultural ailments” in Asia or Africa.

During the agony of traditionalism, the protection of traditional values from external enemies has an enormous mobilization potential, which is usually in higher demand in societies with more unsolved economic and social problems. Poor and underdeveloped countries with a fast-growing population abound with such problems. Acute problems, the absence of alternative ways to solve them, and faith in mobilizing slogans bordering on fanaticism lead to the radicalization of broad social strata. Let me repeat, this is happening in countries where half of the population is under 20 years of age.

They definitely know against whom to direct their radicalism. If women—at least some of them—want to play a higher role in the family and society than in the past, it is not because new demographic conditions make the life of a woman constantly giving birth meaningless nor because they open completely different prospects for her, but because this desire is inspired by western ideas, western education, etc. And Western education is a sin.

This expression “Western education is a sin” in the Hausa language (one of the African languages) sounds like “Boko Haram,” the name of a terrorist group in Nigeria that for years has been terrifying the population in the country’s northeast. In 2014, the group attacked a secondary school and kidnapped 270 female students, declaring that “the girls must leave school and get married.” This was just one of dozens of terrorist attacks in which Boko Haram has killed large numbers of people. In January 2015, Boko Haram burned 16 towns and villages in northern Nigeria, and in March 2015 the group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (ISIS) and began to refer to itself as “the West African Province” of ISIS.

Not surprisingly, terrorist groups in Islamic regions are disguised in Islamic garb. However, the problem is not rooted in Islam. The Khmer Rouge, who committed more atrocities than ISIS and also hated the West, were not Muslims. But the median age of the population of Cambodia in the 1970s, the years of Pol Pot’s genocide, was 17 to 18 years.

The problem is rooted in the intractable economic and social problems faced by the majority of third world countries. Moreover, the problem is multiplied by unprecedented population growth and an inevitable transformation of demographic processes.

MIGRATION: PRESSURE AND OPPOSITION

As clearly seen in Fig. 3, the picture of the growing “demographic overhang” shows that the question of potential pressure from the Third World (Global South) on the “golden billion” (Global North) and the possible consequences could (and must) have been raised half a century ago. This pressure may be due to different reasons and may take various forms.

Perhaps the most obvious is migration. Migrations played a very important role in the redistribution of the population throughout human history. Until World War II, the largest migrations of the recent past were from Europe overseas—to new countries in the Americas or Oceania, or to the overseas colonies of European countries. However, after the war the direction of migration flows changed and Europe turned from a source of migration into a recipient of migrants.

At first the influx of migrants into Europe did not draw much attention, but gradually anxiety began to grow. The scope of migration was not immediately realized. It was only with time that concern over the waves of migrants entered the public consciousness in European countries and even the United States, the traditional haven for immigrants. Active opponents of immigration appeared and attitudes toward immigration became a tool in domestic politics. Recently British demographer David Coleman introduced the notion of a “third demographic transition” to denote a phase in global demographic changes when the scale of migration flows from third world countries begins to threaten the existing ethno-cultural and even political identity of the populations of developed countries hosting migrants.

The question is how the awareness of this threat makes it possible to prevent it. The entire range of discontent with growing immigration—from the academic position of Coleman to the radical slogans of European far-right politicians—only leads to all sorts of suggestions as to how countries accepting immigrants should behave towards them. But what difference do these suggestions make for countries from where the migration pressure comes? After all, they are interested in the migration of their citizens—at least for economic reasons. According to World Bank estimates (which are likely incomplete) the amount of money transferred by migrants to developing countries increased from $18 billion in 1980 to a staggering $436 billion in 2014. Emigration provides at least one outlet for overpopulated countries experiencing job shortages and provides a glimmer of hope to young people who cannot find a niche for themselves at home.

We see how people from poor African countries try to cross the sea in fragile boats, risking their lives and often dying to reach wealthy Europe. And even this is a difficult problem to solve. Are we capable of resisting pressure from the other side and stop migrants?

Migration pressure is the most obvious, albeit spontaneous, form of pressure of the demographic majority on the demographic minority. But there may be more organized, state forms of pressure.

The average Russian is not rich, but Russia is a rich country with the largest territory in the world. It has vast arable lands, which are in short supply in much of the rest of the world. Russia has rich fresh water resources, while neighboring China badly needs such resources. Who can guarantee that someday China will not demand that we share our resources with it? After all, is water not a gift from above and cannot belong to one country? Of course arguments like that do not exist in international law, but is international law always followed? We also have some other natural resources that someone might like to have too.

Russia will not hear such claims from Europe, but why not from Asia? They know that we belong to the global minority, from which we somehow are trying to fence ourselves off. On the contrary, I believe that we should cling to it, because all major problems that Russia may confront stem from Asia.

It is from Asia that we hear the first sounds of a coming storm that we now call terrorism.

THE “MUTINY WAR” OF COLONEL MESSNER

Let us take migrations from which no country can fence off. All countries in the world turned into communicating vessels long ago. Russia now receives the bulk of its migrants from Asia, namely from its “soft Central Asian underbelly,” a term which, I think, was coined by Winston Churchill. The majority of migrants may have peaceful intentions, and I am confident that this is so, but one cannot rule out the existence among them of those with radical ideas coming from the Third World. How can we prevent their distribution and especially implementation in Russia? This applies to all developed countries accepting migrants.

Migrations, even large-scale ones, are common in world history, but this does not mean that all major migrations were peaceful. On the contrary, often they took place as military invasions and conquests. For instance, the Migration Period had little resemblance to the peasant resettlement in 19th-century Russia, and the name of Attila still evokes terror. The military campaigns of Genghis Khan, the Arab conquests, and Ottoman expansion into Europe were varieties of migration.

Many things recur in history, although not in the same way. Even if we assume that the pressure of the “demographic overhang” on the demographic minority acquires a military dimension, this will not be the raids of horse archers or the trenches of Stalingrad. It will be something else.

Of course, groups emerge from time to time like the Taliban or ISIL, which call themselves states and try to establish their own order in a particular area, but this happens inside the third world and does not seem to pose an immediate threat to developed countries. Who would dare attack 21st-century military heavyweights possessing nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles, and all kinds of state-of-the-art armaments?

But this does not mean that they cannot be attacked. Moreover, we see that they are increasingly becoming targets of what we now call terrorist attacks. It is hard to name a country with a high military potential—ranging from Israel to the U.S. and Russia—that has not been subject to terrorist attacks, and these attacks are becoming more frequent. In almost all cases they lead to the third world.

In fact, these are not just individual acts of terror, which have always taken place in history and had a specific goal—regicide, political revenge, intimidation, etc. Instead, this is a special kind of warfare waged by the weak against the strong, using the available means. But this only seems like weakness because attackers rely on unlimited human resources and the boundless fanaticism of their soldiers.

This factor could have been foreseen too in order to prepare for this war, rather than for a past war, which is what peacetime generals always do.

Few people in Russia know the name of Evgeny Messner, a colonel in the Imperial Russian Army, who lived in exile and disgraced himself by collaborating with the Nazis. But today his name has to be remembered because he foresaw the nature of future warfare. In his book Mutiny, or the Name of the Third World War, Messner wrote that in a future war “hostilities will be held not on a two-dimensional surface, like before, and not in three-dimensional space, as it has been since the birth of military aviation, but in four-dimensional space, where the psyche of warring nations will be the fourth dimension.” Messner called this kind of warfare “mutiny war.”

I do not know whether Messner thought of future demographic changes during his work on the book. Most likely he did not. But I do not doubt that these changes have created additional and very serious prerequisites for a global “mutiny war.” Our attempts to respond to the challenges of this war using aerospace forces show that we are not ready for it.